Join us for the workshop that is also a game where we use roleplay to explore how personal and collective data practices and devices might shape the attitudes and fortunes of a society?

Sign up by 12th August 2020

Participants will each receive one of two devices in the post, and will be given different roles to play as delegates in a fictional trade negotiation. In this first meeting on record, and with minimal knowledge of each other’s cultures, the people of Ourland and New Bluestead must use their devices to communicate with each other and to agree to the terms of a technology and data-culture exchange.

What do they have to offer? How will they decide what they want and what is in their best interests?

What freedoms might they sacrifice, what insights might they gain?

How might they adapt a foreign technology to their own needs, and how might they understand the risks involved?

This is an invitation to participate in Transcultural Data Pact, a research event that is also a game of serious make believe. We welcome you to a future-historic event and clash of data-cultures.

The event will take place online in Zoom and will last for about 3 hours with a lunchtime pre-event orientation session that will last for an hour.

There are two sessions available for both the game event and the pre-event orientation (which is a requirement of participation):

Lunchtime pre-game orientation events

13.30 – 14.30 BST Tues 18 August 2020

13.30 – 14.30 BST Wed 19 August 2020

Transcultural Data Pact Game events

13.15 – 16.30 BST Thurs 20 August 2020

13.15 – 16.30 BST Fri 21 August 2020

In exchange for your time you will exercise your creative agency contributing to the ideation of future technologies for live personal data. You might even discover new meanings in your personal data in places you never thought of looking before!

All participants will receive a £20 voucher for their contribution to the research.

This is an open invitation to all. No experience in role-playing games is necessary.

Pregame orientation events

13.30 – 14.30 to learn about your devices and about LARPing, to introduce and develop the scenarios, to build the fictional worlds together.

Game Event Schedule

13.20 – 13.30 Arrive in Zoom and sign in

13.30 Introduction

13.40 – 16.00 Nations Technology Exchange Live Action Role Play

16.00 – 16.30 Debrief, reflection and survey

For any enquiries, please email ruth.catlow@furtherfield.org

Findings contribute to a research paper Human-Computer Interaction (CHI).

The Transcultural Data Pact is a Qualified Selves research event that uses data objects to stretch people’s imagination about the collection and usage of their own data to investigate personal and collective data devices and practices that add real value.

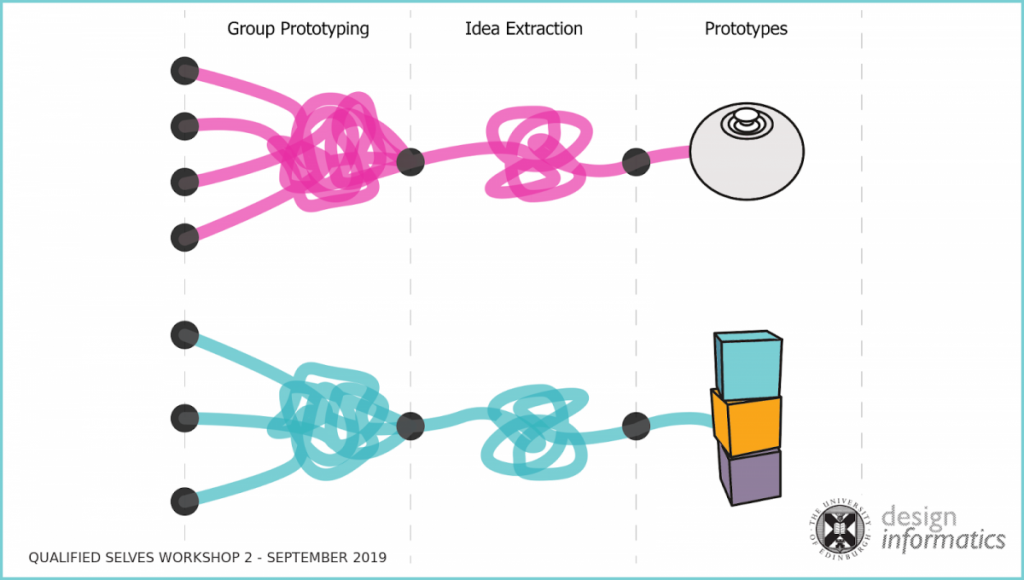

Qualified Selves is a joint project between Lancaster and Edinburgh Universities. Improving how individuals make sense of data management (from social media to activity trackers to home IoT devices) in order to enhance personal decision making, increase productivity, and improve their quality of life. Its novel approach to co-design and co-creation has supported the development of new prototypes to help think about tracking data in different ways. https://sensemake.org/

Transcultural Data Pact is created by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield/DECAL) with Dr Kruakae Pothong, Billy Dixon, Dr Evan Morgan and Prof. Chris Speed from Edinburgh University, in collaboration with Kate Genevieve.

Ruth Catlow is Director of DECAL. Furtherfield is London’s first (de)centre for digital arts. DECAL is a Furtherfield initiative which exists to mobilise research and development by leading artists, using blockchain and web 3.0 technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

Annet Dekker interviews Template, a graphic design and digital development studio run by Lasse van den Bosch Christensen and Marlon Harder. They engage in both client oriented work and initiate their own critical design related projects.

‘The contemporary interface of many digital collections shows images merely in neatly divided grids. How can we create context and meaning for these images?’

As sociologist Mike Featherstone puts it, ‘Increasingly the boundaries between the archive and everyday life become blurred through digital recording and storage technologies’ (2006, 591). Whereas the paper archive has always been the place to store and preserve documents and records, and has functioned as a warehouse for the material from which memories were (re)constructed, its digital counterpart is changing the meaning and function of an archive. The archive’s traditional representational relationship to social identity, agency and memory is challenged by the distributed nature of networked media. Initially designed as a mirror of physical collections and paper archives, the digital repository became a collection itself. A new set of values is presented, but it often remains unarticulated at the cultural and scientific level. What are some of the new understandings of the relationship between the software by which online archives are coded and the social, commercial and organisational practices of what is still considered the archiving of documents? What are the roles of users, in all their manifestations as the meeting point of cultural value and technological systems?

Numerous terms are used to describe the ‘new’ types of archives, for example ‘living archives’ (Passerini 2014; Lehner 2014, 77) or ‘fluid archives’ (Aasman 2014), what is commonly acknowledged is that archives are no longer stable institutions. The terms ‘living’ and ‘fluid’ point to the following characteristic of online archives: openness (they are constantly changing and accumulating), self-reference (hash tags have replaced traditional categorisation), and they represent – like many other online platforms – the shift from passive audiences to active users. Due to their transient quality, it could be argued, these archives are not designed for long-term storage and memory, but for reproduction. As media scientist Wolfgang Ernst explains, the emphasis in the digital archive shifts from documenting a single event to redevelopment, in which a document is (co-) produced by users (Ernst 2012, 95). Whereas the source may remain intact, as in the original archive, its existence is changing and dynamic.

One of the main reasons for this change in archiving is the practice of a variety of non-specialists who are ‘archiving the everyday’ and creating endless ‘personal archives’. This has often given rise to statements about the ‘democratisation of archival practices’, which allows a broad range of individuals, communities and organisations to document, preserve, share and promote (community) identity through collective stories and heritage (Cook 2013; Gilliland and Flinn 2013). What does it mean when archives are thought of in terms of (re)production or creation systems instead of representation or memory systems? Whereas this question has many consequences for thinking about the archive, the design duo Template focuses on how these changes affect the agency of users, by addressing the ways in which users engage with online archives and playfully interrogate and subvert systems such as archives to produce new knowledge concerning their social, cultural and commercial values. With their project Pretty old Pictures, Template addresses the future of online archives and collecting. Whilst critically analysing web 2.0 innovative platforms, particularly Flickr Commons, their aim is to present potential consequences of openness, unclear copyright and ownership legislation, and loss of context in a playful manner.

Template [http://template01.info/] is a graphic design studio established in 2014 and run by Marlon Harder and Lasse van den Bosch Christensen. Marlon studied graphic design as a bachelor at ArtEZ in Arnhem, the Netherlands, and Lasse did his bachelor studies in communication at Kolding School of Design, Denmark. They met during their master studies at Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. With their studio they both engage in research and client practice. Their research projects often relate to their own practice as designers. For example: how labour, especially digital labour, is in flux and how ‘fun’, playing and making friends are new ways to conceal this. Or how the idea of the creative individual seems omnipresent (everyone is a maker) and how digital ‘template-promoting’ tools are stimulating this tendency. However, they argue, instead of the promised individuality these tools generate a very bland sameness. In their client-based work, they do almost everything that relates to visual communication: from web programming to areas where digital translates into analogue (or the other way around), such as Automated books and the conversion of HTML to print.

Annet Dekker: Can you describe the project Pretty Old Pictures and in what way it represents a ‘new’ archive?

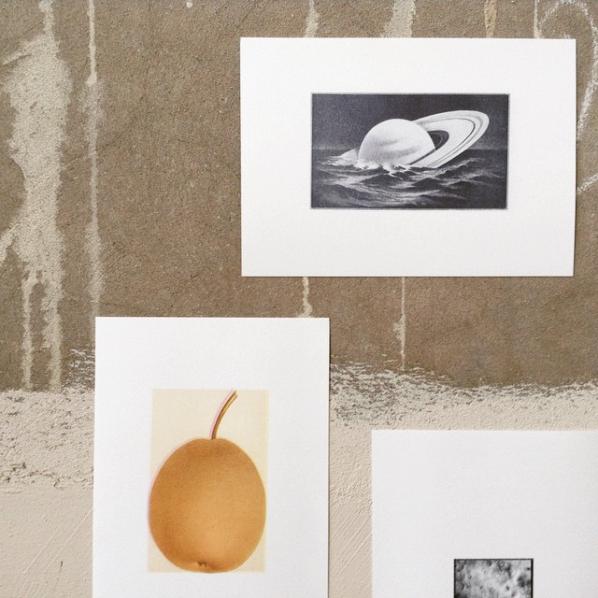

Template: With our project Pretty Old Pictures we are looking into the archive of Het Nieuwe Instituut. Along with many other institutions Het Nieuwe Instituut shares part of its image archive on Flickr Commons. This section of the photo-sharing platform Flickr hosts images with either none or unknown copyright restrictions. The interface of Flickr is extremely visually focused, often displaying an endless amount of imagery lacking any original context. We wanted to explore what potentially can happen to this rather overwhelming content. In a way, these images only exist in the present and attain meaning when a user starts working with them. As such, we believe the ‘present moment’ will very likely become more important in the future where content is extracted from archives and presented as single images unrelated to each other and seemingly without a past. Our intention is to print out specific selections of the images and sell them in nicely packaged bundles.

What were your intentions? What do you want to achieve?

As graphic designers we are fascinated with crowdsourcing platforms and what they stand for: the promise of creative empowerment. You spend four years in an art school learning a trade and then in the real world it is of course not easy to find work. You become part of a broader creative category and especially online there are numerous platforms that turn your trade and your livelihood into un- or underpaid competitions or games, albeit not always in an obvious way. Already at the Piet Zwart Institute [Media Design and Communication in Rotterdam] we became interested in this type of ‘crowd sourced graphic design.’ Take the example of 99Designs. 99Designs is a platform that organises competitions around specific design jobs. For a mere 250 dollars a client often has over 500 designs, made by hundreds of designers, to choose from. For a week we participated in 99 design competitions and made 99 designs that fitted the briefs. During the process we exhibited the designs together with the rejection letters – none of our designs were selected. Rather than being cynical about it, we sincerely wanted to follow this prescribed anticipation of 99Designs and see where it would lead us.

We were interested in how feasible it would be to make the designs, how many hours it would take and in return what our profit would be. Secondly, how much exposure it would generate and if it would broaden our network, which is a main motivation pushed on to designers using these platforms.

Similarly, we looked at other business models like Etsy that all have this same promise of generating an income for your ‘unique products’. When browsing their database it soon becomes apparent that the products are not unique; there even seems to be a very specific Etsy aesthetic. In the end, these platforms tell you more about a specific period in time than anything else. From these experiences we became interested in starting our own company to see how we could benefit from the trend. And then we saw all the content on Flickr Commons and how hardly anyone is using it in the way these other platforms are using content. We wanted to see how easy it would be to make a business out of it: to live the dream of creative entrepreneurs!

Basically we want to comprehend how these institutions are dealing with their digital archives, especially when publishing the content online. In the meantime we confront them with what could potentially happen. There are many possibilities, from selling to copying and changing the images. We want to investigate the consequences of those actions. For example, what does ‘open’ content mean, what are the consequences not only in terms of copyright, but also for the institute and its archival tasks. Are museums following a general trend or are they idealistic about spreading information, or both, and what does that mean in relation to traditional methods? More generally, what are the effects of a changing image culture with regard to new ways of dealing with decontextualized content, appropriation, or even the influence on cultural – and individual – memory? With this project we want to poke at all these issues by actually doing and setting up a business.

At the same time, we are interested in the influence of the online platform that is used. What happens when you give away content to a commercial business, which then becomes a co-owner of the material? This is not necessarily a new question, but it is becoming more urgent now that bigger platforms are offering these easy solutions. In a way it resembles the Google Books project in which many libraries and publishers gave away rights just to have their books digitised. These issues are far less resolved within Flickr Commons, or by those uploading – or downloading – the content. It all happens without people being truly aware of the consequences.

Why did you focus on Flickr Commons, rather then other large repositories, databases, or archives like, for example, Europeana?

We started looking at what sort of external databases and platforms Het Nieuwe Instituut is using, and found out that Flickr Commons is one of the more central, and definitely the biggest. Flickr Commons is interesting because of the promotion of public domain and ‘openness’, using guidelines on copyright that seem purposely unclear. Each image under Flickr Commons is tagged with ‘No known copyright restrictions’, meaning that either the image is in the public domain or that the author cannot be verified or found. Additionally each participating institution has its own rights statement, some of which loops back to the Flickr statement and therefore remains ambiguous or even contradictory. This leaves room for interpretation and opportunities from both Flickr as a platform but also other third parties, like us.

The interface of Flickr also caught our interest. Once you enter the website you see a vast amount of images, infinitely scrollable. Some museums have millions of images on Flickr, which is served up visually as an extremely fragmented image collage. Rather than offering the original context of an image, the system functions primarily through visual linking. That’s how a new context and meaning is made. Of course if you know what you are searching for and manage to type in the right search query you can get relevant results, but this will never match the expertise or human-provided knowledge that is found in a traditional archive. This is what we found fascinating when visiting the physical archive of Het Nieuwe Instituut, where the archivist explained all kinds of relations between documents, offering additional information that you would not necessarily be looking for. We realised what is missing in many online archives or databases right now, and more so in the future, since this kind of human knowledge, built up over time, does not transfer easily. Of course there are descriptions, categories, and keywords based on folksonomies on Flickr, but there are no stories – at least not yet.

Do you use specific criteria for the selections you make?

At first it was merely based on our own favourites. Now we are also looking more at things that are popular, that sell on platforms like Etsy. Often these are the regular things like nature, space, and architecture of course, but we are still testing. For Het Nieuwe Instituut and other institutes partaking in Flickr Commons, Pretty Old Pictures creates custom packages. These are sold in their museum shop, perhaps used as business gifts, merchandise or advertisements. Design-wise we grasp the DIY [Do It Yourself] spirit and this is essential for our strategy. For example, we make our own envelopes for the images we sell, which neatly transforms into an image-frame. They even smell of the laser cutter that we used.

There is such an overall emphasis on all kinds of retro trends, from old school barber haircuts and beards to riso prints on vintage book pages and moustaches on t-shirts. Trends we do not necessarily try to understand, but feed into our project. We are at the same time following the hype and trying to create hype: all in pursuit of a genuine creative business.

What is your relation to the material you selected? Is it ambivalent, or are you complicit – buying into the creative promise?

It is both. On the one hand we feel a bit ashamed, because at times it comes across as ripping someone off. On the other hand we are very excited about the project and looking forward to what may happen. There is a tension between these elements, which we also want to enforce and play with.

Your studio Template also seems to have two sides. On the one hand you make a critical nod to templates and on the other hand your work is about playing and using templates in slightly different ways. Similarly, an interface directs what you can do, and now you are building your own interface. You work seems rather paradoxical.

Yes, we use templates as topics for our research, but then we refuse to use them in our commercial projects. You know templates exist and it is really hard to avoid them. Because of their ease of use it is also completely understandable that people use them. It does not make sense to be completely negative about them. However, of course we like to be critical and subversive in our use of templates. Often the very limited possibilities or options of the template enhance the feeling of having made something. You created something original, that no one ever thought of or will do again. However, you created it within a framework that dictates what you can and cannot do. All these platforms and DIY mechanisms very much play on the assumptions of the importance of the original, the authentic and the individual. Essentially, these are still important beliefs in art traditions and our culture at large.

Most of these discussions also link to the debate on free labour; sometimes you feel in control when using all these readily available tools, but at the same time you are losing your power, because you are giving up the content and work that you create. We have no idea what 99Designs, for example, will do with the 99 designs that we made: they might sell them to different parties, use them to create new templates, or just delete them. Then again, communities get formed on platforms, and seeing other people’s work might in turn benefit you in some way or another. Some platforms even organise special lunch meetings, and the relationships between users have been known to outlive the platform itself. It is too easy to just be dismissive of it all.

Where is the breaking point for you; when will you, or the user, become more powerful than the other?

For us it is important that the design part of the project functions in the way it should. We want to create something that is convincing. In more general terms, it is important how people are addressed, what agency they get and how much freedom they have to use what they created in other ways or places. Of course the failures never receive any attention: the focus is on the success stories as they help promote the platform. That is the point where things start to derail. It may also go wrong when more obvious commercial stakes become apparent. For example, at a certain point Flickr started to sell images from its users licensed under the Creative Commons, causing a scandal amongst angry users who saw their content being commercially appropriated by Flickr. Likewise, we would also be very happy once we can sell the archive back to the organisation to which it belongs! Then again, we would just continue the cynical part of the project, which is not the most interesting part. It would be more interesting to discuss the situation the organisation has created for itself.

I am particularly interested in the idea of sharing and circulating images and other information that is made possible with Flickr Commons as a new form not just of distribution but perhaps also production – and archiving. In what way do you play with these kinds of mechanisms? Do you think it brings out a new potential in archiving?

These collections of images are open, so essentially you can do what you want; digital archiving is really made for interpretations. It demands a much more active role from its audience. They can provide context to the images without having to follow any rules. This would be unthinkable in a traditional archive. At the same time it brings up the question of what the role and function of an archive is. The relation to the past seems to disappear. It is only the present that counts, which is linked to the near future; the excitement of other people’s reactions and how they will respond. Most likely the two ‘archives’ will exist simultaneously, because at a certain point we will need to go back into history. The real question is how we will be able to return to the past in a digital archive, in which context is very scattered, and based of rapidly changing folksonomies rather than standardised categorisations.

In a way it could be argued that your project follows the same ideas as many creative industry start-ups: focusing on future business, economic models and sometimes even utopian perspectives. But at the same time, you work from the present, which may not be obvious to everyone, but is still very relevant as it is changing the way we deal with property, archives and memory.

One of the main things that is often missing in these discussions are the users: they are somewhere in the background, invisible. However, in this project we are replicating this system by focusing on the platform, and not necessarily the users. The physical archive of Het Nieuwe Instituut was a valuable experience for us. It became so clear that the knowledge the archivist possesses is unique and this kind of contextual information is hard to replace in a digital environment. Rather than trying to bring that into a digital environment we wanted to expose other layers, other ways of using and perhaps abusing the content that is void of context. Essentially today’s image culture is hard to grasp, it is partly steered by mechanisms and systems that are working in the back-end, which makes us use images in different ways. Archives are transforming from places where memories are kept to databases in which the present and near future are becoming more important. It is all about the now, presenting and sharing your, or other people’s images with friends and strangers alike. The context of an image is not important anymore; it is all about form and ease of distribution.

This, of course, throws up interesting questions: how do we relate to these images, how does this culture influence us, now and in terms of how we think about the past? Are we taking the image – and its content – for granted? In a way images – and perhaps archives – also become meaningless, or at least the importance shifts in favour of relations and communication between people. We tend to think that selections are still important: similar to the archivist we make selections that may seem random but the constraints generate meaning. Not necessarily the same ‘original’ meaning, but a selection brings something new, it makes people think in a different way about the images. Connections are thought of and narratives appear. Such creative thinking is of course easier with a selection of five than with hundreds of images. This new way of dealing with the content of the archive is no longer related to singular objects but meaning is generated through different constellations. Similar to oral culture, events and histories are now retold in different ways. As such it could be argued be that the (future) digital archive has more in common with oral traditions than with its paper version.

Pretty Old Pictures is commissioned by Het Nieuwe Instituut as part of their ongoing research ‘New Archive Interpretations’ (curated by Annet Dekker). For more information see http://archiefinterpretaties.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en

Template are part of the exhibition: “Algorithmic Rubbish: Daring to Defy Misfortune” @ SMBA in Amsterdam, with Blast Theory, James Bridle, Constant Dullaart, Femke Herregraven, Jennifer Lyn Morone, Matthew Plummer-Fernandez, Template, Suzanne Treister. The show runs till 23 August with a final day discussion that includes Template and Constant Dullaart, moderated by Josephine Bosma. For more info: http://smba.nl/

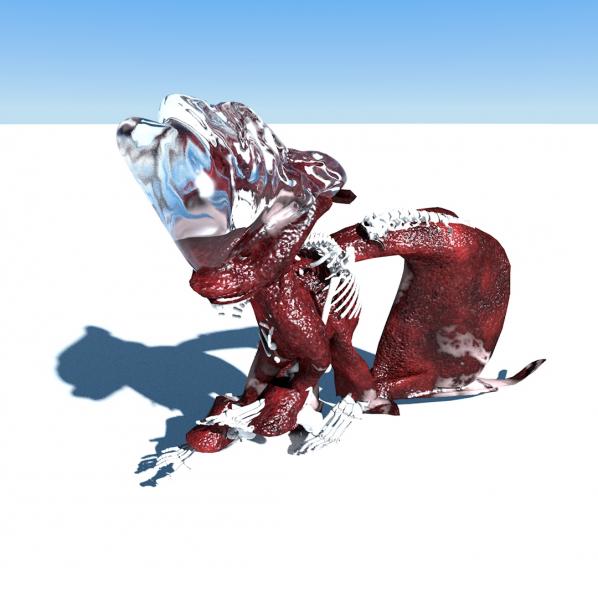

Structures. Something has been built, grown, stretched. Maybe skin, maybe a web, maybe a protective barrier – it is a plastic protein emitted by an organism in order to increase its survival opportunities, it is a food matrix for its offspring which thrive on glossy resin. You can travel across it and it can easily be mapped, although not by humans.

We can’t say anything about it – we can speculate everything about it. It is something possible or as the author says another reality. The real is replaced by the potential. This is one of a series of works by St. Petersburg-based artist Elena Romenkova. The works are glitches, abstract distortions, alien expressions of what for her is a subconscious realm.

A portal. You are entering the rainbow world contained within two concentric eggs within the grey world. This is light, reflections, haze, indescription. It looks inviting. The colour spectrum is odd, the whites creep up on everything else, the shape of everything is strange. Basic synaesthetic rules are inapplicable at the rainbow/grey world junction.

There is nothing that this image, by French artist Francoise Apter (Ellectra Radikal), has in common with Romenkova’s. They are united only by their adherence to strangeness, a technically created vista that looks like nothing we know. A world not of local cultures, but of computational production. Here anyone can know anything, it doesn’t matter where you’re from.

What is culture when locality is secondary to epistemology? What is knowledge when the portable device takes precedent over your situated environment? Worlds are built around us, sophisticated electrical spaces, they travel where we travel, and only after do we factor in the idiosyncracies of specific geography. If the banal experience is one of nomadic alienation, of search methods based on no place, what does the role of culture and art become? Everyday life is a subject for hypothetical language. The digital commons is a species of posthuman that communicates via speculative misunderstanding.

Korean artist Minhyun Cho (mentalcrusher) shows us what the dinosaurs really looked like. When you put the meat and scales back on. He shows us what an ice building being looks like in the shadow of terminal cartoon winter. How rubber can be used to erect sculptures and bones can be taken out of museums and put to good use in civic architecture. No one is around to see this, but still the idea sets a precedent. Crown each ghost with ice mountain prisms.

With visual language, very quickly we get to a stranger and more indeterminate range of science fiction possibilities than narrative tends to map out for us. How much imagination is possible, and how much does our internal experience match anything presented around us. If our environments advance exponentially quicker than any generational or traditional mythology, what sort of language can we have for expression? The maker’s invention precedes the reception of form. Innovation is a matter of banal activity, communicating an experience of the real which is never the same.

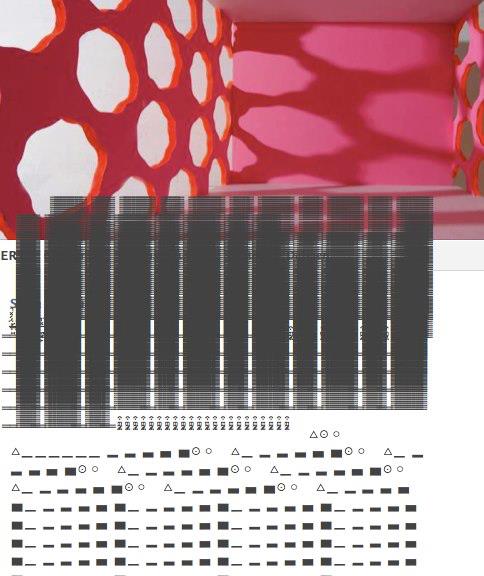

And now an eyeball. Triangles. A vessel. To Cho’s blinding world of light, Spanish artist Leticia Sampedro responds with a featureless darkness. All absurdities once on display, now they recede into nothing. It might be a mandala, perhaps an artifact from the ancient future, a portable panopticon that fits conveniently on your desktop. Your feelings are here, your peculiar distances, everything’s reflecting off the glass, the metal, the camera. You are the mirrored fragments of an invention we’ve lost the blueprints to. Foresight the womb of a disembodied politics of community.

Community held together by structures. In German artist Silke Kuhar‘s (ZIL) work, we enter into one of these structures. Inside we find hallways, a nice selection of windows and all kinds of data – scripted, graphed, symbolized. This is the plan for the future. I hope you can read what it says. Her work meshes spaces with collapsing foreign constructs – if we can just read the language we’ll know what to do. But no one reads it, and no one wrote it. This is a building without inhabitants – architecture without people. Democratic ballots are automatically filled out by a predetermined algorithm. Your agency is a speculative proposition for popular media – people collaborate with you, but they can’t be sure where you are, when you wrote, and if you really exist as such.

No people. This is a unifying principle. Cold, silver, streams. Machines in the sky. Silicon waterfalls, diagonal. Civilization distilled into physical patterns, an obtuse object photographed in another dimension. What is the word for reality again. What is the word for scientific investigation? A Venezuelan based in Paris, Maggy Almao’s abstract glitch world is silent – it’s a gradient, it’s some illusion of partial perspective.

What is the language to talk about the world? If we turn to artists’ visualizations, what does that tell us about languages we speak, and ones we read? What does the graphing of incomprehensible mechanisms tell us in turn about art and its history? The machine’s narratives tend to drown out any functional reality. Genre storytelling tropes become repurposed as collective cultural ideas. Conceptual works are followed by pragmatic speculation, medium-centric analysis replaced by experimental failures. You can never get a fictional experiment to work.

Science has indelibly entered the art field, for each of its medial innovations it requires further attention in terms of its technical makeup. Half the work is figuring out what the canvas even is, we are building canvases, none of them look alike, and their stories read like data manuals. An aesthetics of unknown information.

This is the homeland. The homeland is mobile and has many purple bubbles. It’s an airship from the blob version of the Final Fantasy series. It has satellite TV to keep in touch with the world. It has some tall buildings so you know it’s civilized. It is part of Giselle Zatonyl, an Argentine-born Brooklyn-based artist’s opus which deals comprehensively with science fiction ideas and their implications.

The ship travels, where the culture originates is more and more unknown. It is technically divided, access is the key, we can worry about language and culture later. We are still embodied, still located somewhere, but all this has become subject to the trampling of scientific mythologies, where their utilities might go, and where their toys are most needed. Crisis is a genre now, about as popular as time travel. You are now free to dream up whatever future society you wish, and subjugate whatever cyborg proletariat your heart desires. In the realm of speculation, anything is possible, and nothing is fully acceptable.

The themes of internet art production give us some language, some set of visions that tell certain stories – works found throughout the internet, posted in communities, shared online – sometimes part of gallery exhibitions or products, sometimes not. You get a profile, some social media pages, build a website, you begin making, sharing and remixing images. Folk art is a subsidiary of new media art – social sculpture meets internet content management systems. A language for political engagement based on the creative activity of speculation. Scientific dreams for a technological commons.

Dreams where sight is physicalized into complex data graphs. Where Sampedro’s portable gelatin panopticon is cloned into a regularized matrix. Inspired vision is just one aspect of algorithmic predictability. In Taiwanese artist Lidia Pluchinotta‘s visual work, the cloned image is central. Mechanical reproduction, skulls, spirals, symbols, the internet has it all. Civic participation has never been so mathematical, observation never so multiple.

Inside the city, architecture is actually a colour-coded map that helps you find the store you’re looking for. The map is the territory except there’s no info on how to read it. We are here, we are home, but the walls of the buildings were designed by some specialist that we haven’t met yet. Stairs, depths, the complex and layered constructions in Canadian artist Carrie Gates‘ work aren’t quite one of Zatonyl’s buildings. More fragmented, more saturated, more chaotic. It’s speculated that people could live here, although we don’t see them anywhere. Not yet anyway.

The maelstrom of technological progress presents us with the need to adapt our participation and rhetoric accordingly. Science fiction is a folk language for common experience within a technoscientifically oriented world. These images are imaginative products of social and participatory artist communities who, when marrying the personal and contextual, create speculative objects of general strangeness. Their description is nothing less that one of alien entities – alien entities that are everywhere. Earth is the most sophisticated foreign planet we’ve yet to invent, we just need to discover how to populate it.

Featured image: Pablo Garcia’s presentation at Resonate 2014

Resonate, the Belgrade, Serbia digital arts and design festival, now in its third year unfolds over a long week at the start of April. Its central tenet is to bring together “artists, designers and educators to participate in a forward-looking debate on the position of technology in art and culture.” It is also an emerging and challenging festival that raises many more questions than it answers. The festival starts off with a number of workshops held by practitioners for practitioners. Foregrounding the demystification of the creative process immediately sets it apart from any number of other media arts festivals. Whereas many festivals might be broader in their approach to what the digital can include, and focus on themes that don’t always feel like they directly influence what happens in the festival, Resonate doesn’t give itself a curatorial focus. But, and so, the workshops set the festival off with a focus on making. Most people who come to Resonate are just that: makers of work. It feels as though there are fewer curators, producers and academics here than you would expect.

Resonate, the Belgrade, Serbia digital arts and design festival, now in its third year unfolds over a long week at the start of April. Its central tenet is to bring together “artists, designers and educators to participate in a forward-looking debate on the position of technology in art and culture.” It is also an emerging and challenging festival that raises many more questions than it answers. The festival starts off with a number of workshops held by practitioners for practitioners. Foregrounding the demystification of the creative process immediately sets it apart from any number of other media arts festivals. Whereas many festivals might be broader in their approach to what the digital can include, and focus on themes that don’t always feel like they directly influence what happens in the festival, Resonate doesn’t give itself a curatorial focus. But, and so, the workshops set the festival off with a focus on making. Most people who come to Resonate are just that: makers of work. It feels as though there are fewer curators, producers and academics here than you would expect.

This year, shifting location from 2013’s Dom Omladine, perhaps learning from some of the problems of last year’s over-heated and occasionally too-tightly packed events, they have moved to a spread of venues, with the base being the Kinoteka Cinema, a sleek-looking modern building with a number of different spaces. Any decent festival has a spread of overlapping events making it impossible for one person to attend everything. Resonate makes no apologies for being just as packed with events as any other festival. The one time it might be possible to sit and spend a day in one place is if you’ve managed to get on to a workshop event that takes place on the Thursday. Once the workshops are over though, Friday kicks off with the panels and presentations. Choreographic Coding discussion, led by NODE Forum’s Jeanne Charlotte Vogt opened the panel discussions. A broad ranging talk with Raphael Hillebrand, Florian Jenett, Peter Kirn (CDM), Christian Loclair and Klaus Obermaier, (returning again after last year’s Resonate, possibly being an ongoing presence at the festival). All of the panel talks took place in the central lobby of the Kinoteka, which proved to be a terrible choice for anyone who wanted to actually hear the speakers. At times the discussions descended into a barrage of mumbles blending with the sound of people emerging from surrounding presentations and the poor choice of PA equipment placements. A shame, as the themes for these were well chosen, including Ways of Seeing, chaired by Greg J. Smith of HOLO magazine, and Generative Strategies, across the Friday and Saturday. The best laid plans of mice and journalists. I had planned to interview a number of presenters during the event, key amongst them was Pablo Garcia, who was on a panel and presented his own work on the Saturday. Apart from a brief conversation, we finally caught up over email several days later. I fired a number of questions at him, which are dotted across the rest of this review.

Do you find that Resonate offers something different than some other digital festivals? If so, what might that be? “It feels a lot like some of the better festivals I have seen, like EYEO. It is selecting from the best digital artists/makers out there, and giving them free reign on the stage to talk and share. The city has a great vibe and the overall feel is truly a “festival”, and not so much a conference or academic gathering.” ~ Pablo Garcia.

Friday’s talks included Cedric Kiefer (Onformative) giving a presentation in Gallery of Frescos, a short hop and stumble from Kinoteka Cinema. I’ve always enjoyed the juxtaposition that occurs when digital media is presented in contrast to, in this case, a venue “exhibiting in one place the highest achievements of Serbian Mediaeval and Byzantine art.” In other words, old stuff that enforces the modernity of the digital work we are being shown. Kiefer’s presentation covered some of their major projects including their work for Deutsche Telekom which used the company’s Facebook interactions to create beautiful data visualisations (Facebook Tree – 2013). There’s an unabashed acceptance of the interaction between corporate funding and creativity on display with many of the presentations. It’s something which never provokes debate, at least not in any of the conversations I had with participants or the panels I attended. Maybe that’s no longer ‘a thing’ that concerns creatives and the money required for some of the bigger projects has to allow for corporate sponsorship? I’m not suggesting we shouldn’t embrace funding from wherever it comes, it would just have been nice to have some debate around it.

The schedule for the whole festival is broad and busy. There’s no chance of making it to every presentation or discussion, which is a great reason to go with others or to make an effort to talk to other attendees about what you’ve seen. The festival is a research port of call for many established, practicing digital artists. The UK’s Ludic Rooms have been to the past two festivals and consider it an opportunity to engage and re-establish contact with their peers in the community. “It is a coming together on an international scale with a thoughtful focus on practice,” reckons Ashley Brown, one half Ludic Rooms. Co-Director Dom Breadmore adds, “for us, Resonate has quickly superseded other events to become an annual pilgrimage for discussion and inspiration.”

One of the final presentations of the festival is by Daito Manabe in the Kolarac, another add-on venue of the festival, again an improvement on last year’s Dom Omladine. Daito’s work reflects something of the current state of digital media work. His presentation includes his (literally) home-made research videos, as well as the documentation of bigger projects. Whether he’s attaching electrodes to his own face to see what the effect is (hilarious facial distortions in this case), or working with dancers to create a drone/dancers piece, there’s humour and an enquiring mind at the center of his work. Daito showed his Ayrton Senna project, using the data transmitted from Senna’s car during his world-record lap in 1989, an ambitious and challenging project, least of all being the decision to erect it on the original racetrack. The data is used to trigger LEDs and numerous speakers laid out on the course. The LEDs follow the path taken by the car, while the sound is the engine accelerating and decelerating as the car would have taken the corners. It’s a ghostly piece, at once recreating that frustration that race fans must have of just having missed the car and a reminder that this is an event that happened many years ago. An echo of the past. Data mining, big data, is like this, in most contemporary projects. Data visualisation is a zombie, rising up to challenge the present. And like all the best zombie films, it can be a metaphor for our own rampant consumerism and reliance on technology. Still, at least in the hands of someone like Daito, our guilt is assuaged by humour.

What is your own take on the current landscape of digital media/art/design? “It’s an exciting time, for sure. Not only because there is so much digital access today for all to experiment with. We are starting to see makers move past the “wow” phase of tech and really start to integrate digital techniques into various historical techniques. Watching digital work cease to be about digitality will go a long way to opening new avenues of exploration.” ~ Pablo Garcia.

In those important few hours after a festival when you make your way back home, you finally get a chance to take stock. Thoughts crash over you in what better place for free-form thinking than the nowhere of airport waiting zones. In the neverzones I realised that what I’d thought was my frustration with Resonate, was actually the thing that gives it a unique flavour. Resonate doesn’t present a theme and then hope to find an answer through precarious curation of speakers who most likely will follow their own path anyway. What it does do, and does well, is ask questions that might not have answers. The focus on knowledge and learning gives attendees a broad enough palette to choose their own ambitions for the festival. There isn’t any guided pathway through the diverse range of speakers. There are many things that Resonate could do better. It would have been nice to see more actual work in the various spaces. Line of Sight, a collaborative project by Kimchi and Chips and Nanika, (produced by CAN_LABS and Resonate Festival) was installed and produced for Kinoteca goers during the festival, giving a taste familiar to many attendees, of the stress of having to deliver a working project to a tight deadline. Thankfully, they did so. More projects would have been nice though. Even the digital needs to explode out of the screen and smear itself across a few walls or public spaces, obstructing and challenging people around the venues. After all, contextuality is nine tenths of the art law. Equally, some of the audio/visual problems need addressing. Complaining about them seems like a mean sideswipe, but these are the things that leave people with the suspicion that a festival isn’t as bothered as it should be. Resonate does care about attendees, as is evidenced by the free workshops and focus on helping to develop practitioners. It reflects this in its very DNA as an ever-becoming environment for creatives. And besides, the good stuff always happens in the rough and frayed edges. Resonate needs space and time to stretch and breath and see what it can become, just as Serbia, despite a rich and ‘interesting’ history (Belgrade is one of Europe’s oldest cities) is still finding its feet in the modern world (it applied for membership of the European Union in 2009). The festival supports emerging digital media practitioners by accelerating interaction with other countries to support the country’s upper-middle income economy with its strong service sector economy.

What was your experience of Resonate? “Resonate is a jam-packed, head-spinning experience. So many amazing people showing all their goodies in tightly packed spaces. It’s a lot of fun. Caveat: don’t go expecting to see everything. So many events and talks are happening simultaneously, you can’t see it all. Personally, I found it incredibly valuable to be able to show my work to a really talented and smart group of people to get solid feedback on what I do. I learned a lot by presenting and by seeing sympathetic artists.” ~ Pablo Garcia.

As the festival evolves, it would be nice if it smoothed out some of the frayed edges. But maybe this isn’t possible without allowing the freedom the open spaces allow for the fun stuff to happen. As Daito Manabe’s presentation showed, the open, unordered spaces are where all the best artistic developments take place.

Featured image: Sam Meech, Punchcard Economy, 2013. Photo courtesy of FACT.

The new exhibition “Time & Motion” at FACT in Liverpool, UK, takes the pulse of punchcard protocol and creative capital in our own “Modern Times”.

The exhibition Time & Motion: Redefining Working Life at FACT Liverpool is a collaboration between FACT and the Creative Exchange at the Royal College of Art – an initiative which looks at how arts and humanities researchers can work with industry to effect digital innovation. Rachel Falconer reviews the exhibition in the context of the paradoxical dynamics of cognitive capital and the changing landscape of the labour market.

Now self-employed,

Concerned (but powerless),

An empowered and informed member of society

(Pragmatism not idealism),

Will not cry in public,

Less chance of illness,

Tires that grip in the wet

(Shot of baby strapped in back seat),

A good memory,

Still cries at a good film,

Still kisses with saliva,

No longer empty and frantic like a cat tied to a stick,

That’s driven into frozen winter shit

(The ability to laugh at weakness),

Calm,

Fitter,

Healthier and more productive

A pig in a cage on antibiotics.

Fitter Happier, Radiohead.

The frantic quest for the elusive Shangri-La of work/life balance is a neurotic luxury afforded only to the always-on, hyper-connected generation of precariously unstable home office workers[1] in our hypercapitalist society. The working rhythms of this emergent class of “precariat” [2] are far removed from the forensically prescribed scientific management resulting from the time and motion studies associated with Taylorism at the beginning of the last century. This shift in working patterns generated by the digital revolution is the primary focus of the exhibition Time and Motion, Redefining Working Life currently at FACT, Liverpool. From an archival, filmic view of the automated, (Western) industrial factory labourer to contemporary portraits of the global information worker’s state of perpetual imbalance and non-stop, hyper-connectedness [3] the participating artists expose the – often contradictory – ecologies of labour, consumption, and the conditions in which they operate. The exhibition also marks the collaboration between FACT and Creative Exchange at the Royal College of Art – an initiative which looks at how arts and humanities researchers can work with industry to effect digital innovation and confront contemporary modes of production.

Taking the archival stimulus of time and motion measurement as its title and industrial work patterns as a starting point, the exhibition Time & Motion is the latest in a series of exhibitions and symposia addressing immaterial labour and new working patterns in the age of globalisation and creative capital.[4] Rather than following the well-trodden path of casting the figure of the artist as digital labourer, or attempting to portray an expansive, post-colonial view of nomadic, labouring diasporas, Time and Motion reflects a more subversive and fragmented approach to the politics of work, rest and play in the global information economy.

Sam Meech’s Punchcard Economy is at once a homage to the textile industry and a recognition of the contemporary precariat. With more than a symbolic nod to northern England’s textile heritage, Punchcard Economy consists of a machine-knitted reinterpretation of the Robert Owen’s 8-8-8 ideal work/life balance.[5] The piece was produced on a domestic knitting machine using a combination of digital imaging tools and traditional punchcard systems. During a residency at FACT last year, Meech collected punchcards from visitors detailing their working hours. This data was then translated into a knitting pattern which was used to generate the final work – a banner depicting the contemporary working day. Any hours worked outside the eight-hour day appear as a glitch within the fabric. This banner – historically a symbol of the working class and trade unions – also denotes the fragmentation and blurring of national class structures in the era of globalisation.

The move towards a flexible, open labour market has not eroded the class system completely, but a more fragmented global class struggle has emerged. The “working class”, “workers”, “proletariat” are terms that have been embedded in our (Western) culture for centuries, and used as badges of honour by some, and terms of derision by others. By incorporating a large cross-section of working society under one banner, Meech has literally – in stitching different socio-economic groups together into the very fabric of the working day – rendered the once potent archaic class signifiers as little more than evocative labels.[6]

“75 Watt” by artist Cohen Van Balen and choreographer Alexander Whitley also riffs on the trope of the long fought for 8 hour working day. Deriving its title from a quote from Marks’ Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers: “A labourer over the course of an 8-hour day can sustain an average output of about 75 watts”, the film is a subversive ballet of the complex and often skewed relationships between production, consumption and distribution in the post-industrial age. The film features a group of Chinese labourers working an assembly line, (playing on the stereotypical “Made in China” trope). The object they produce, however, has no logical use. The purpose of the exercise is simply to choreograph the combined movements performed by the labourers in the manufacturing process. The work examines the nature of mass-manufacturing on differnt levels; from the geo-political context of hyper-fragmented labour to the bio-political condition of the human body on the assembly line. Echoing the Taylorist ideal, here we see engineering logic taken to its conceptual extreme; through the scientific management of every single movement we witness the passage of factory labourer to a man-machine.

By shifting the purpose of the labourer’s actions from the efficient production of objects to the performance of choreographed acts, mechanical movement is reinterpreted into dance. The artists ask: “What is the value of this artefact that only exists to support the performance of its own creation? And as the product dictates the movement, does it become the subject, rendering the worker the object”?

This operatic construction line also points towards the ultimate failure of scientific management. Taylorism was always dictated by the needs of capitalist exploitation, but in its pure form it proved to be inefficient in drawing on workers’ talent and potential. In time the bourgeoisie recognised the inadequacies in Taylorism, and Taylorist methodology was mostly withdrawn by the 1930s. However, this was not the end of time and motion measurement. More recent management theories include Theory X and Theory Y introduced by Douglas McGregor in the 1960s.[7] Contemporary Taylorism takes the form of the Lean practices introduced into major departments of the British civil service (including HMRC, DWP, MOJ, and MOD). Workers incorporate “efficiency savings” as an integral part of their job, and work priorities are monitored by the soft panoptic gaze of non-hierarchical “collaborative practice”. Here,workers time their work processes, identify forms of waste, and propose changes in work practices. This “bottom-up” approach goes hand in hand with the new language of management – as managers morph into “leaders”. As efficiency savings are made from workers’ suggestions, the “leaders” try to enforce impossible targets, and decide whose post is next to be eliminated – hence the creation of the precariat. As part of the precariousness of employment, workers not only worry about losing their jobs, but also have to propose measures which, in the name of efficiency, might put them out of work. Added to this the increasing automation of work and the burgeoning AI scene, where does human cognition stand in all of this?

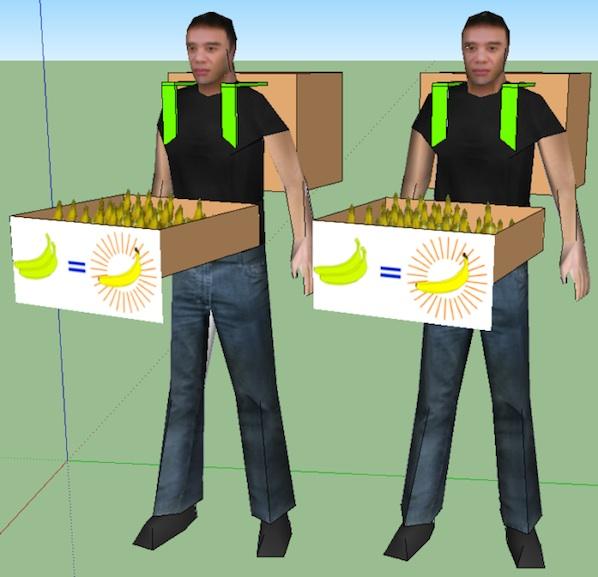

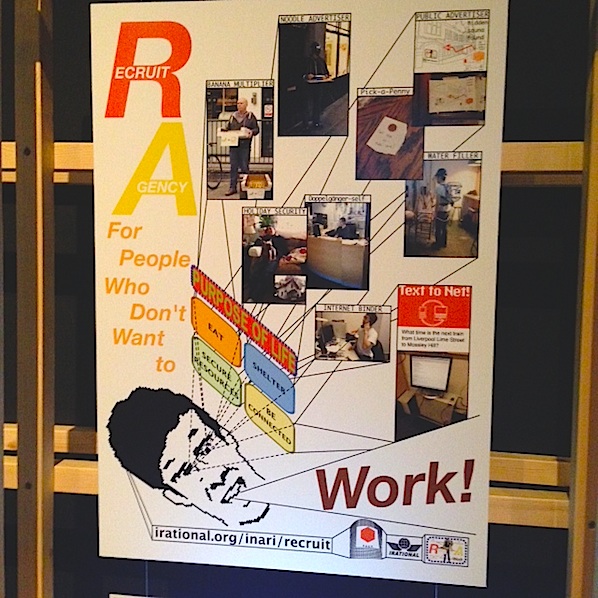

Inari Wishiki’s set of ludicrious alternative employment models (such as Banana Multiplier), are in reminiscent of the subversive, performative models of the Fluxus movement. Inari’s online work Recruit Agency for People Who Don’t Want To Work dramatizes this staging of an alternative labour market. The website includes documentation of a series of performances by the artist exploring the premise that with the proliferation and development of technology, we as humans have lost our place in the world of work, and yet still need to appear to be “useful” in order to earn a living.

Recruit Agency For People Who Don’t Want To Work is a set of systems which allow people to engage in the act of commerce while abandoning “all the meaningless rituals of having to be useful in order to earn money”. In INARI TRADING CARD, the artist documents the way in which “essential” workers function as a social infrastructure. He observes that “money was naturally following those workers according to their essential motions, unlike that of workers who seek after money”. These set of performances are an ironic counterpoint to the hyper-efficiency promoted by neo-Taylorism, and point towards the informal norms that are in tension with the industrial time norms still permeating social analysis, legislation and policymaking in the globalization era.

In his text “The Value of Time Spent” in the accompanying catalogue to the exhibition, Mike Stubbs supports this strategy of “design for disassembly” and novel values of exchange. Stubbs maintains that these alternative ecologies of exchange are necessary in order to allow us to question how we spend our time, and for us to lay bare the new patterns of professional fulfilment and social relations inherent to our hyper-mediated society.

The classic distinction between the workplace and the home was forged in the industrial age, and when today’s labour market regulations, labour law and social security systems were constructed, the norm was a fixed workplace. This model has now fragmented and crumbled and the term social factory, popularized by Tiziana Terranova and others, is applied to describe this shift “from a society where production takes place predominantly in the closed site of the factory to one where it is the whole of society that it is turned into a factory – a productive site”.[8] The production is one of value, where the collective efforts of intelligence and creativity are networked, controlled and exploited. Labour takes place everywhere, and the discipline or control over labour is universally exercised. But policies are still based on a presumption that it makes sense to draw sharp distinctions between the workplace and home – and between workplace and public space. In a tertiary market society, this model is obsolete, leaving the information worker increasingly pressurized and isolated.

One of the recurring themes in Time & Motion is this hybrid and compromised locus and infrastructure of the work place. Harun Faroki’s moving image work A New Product presents an insider’s view of the paradoxical construction of so called “fluid” working environments. He describes his new film as: “Scenes from meetings within a company which advises corporations how to design their offices — and the work done there. The film shows that words are not just tools, they have become an object of speculation.” In this work, he stages the brainstorming sessions of a business consultancy specialising in the design of workspaces, offices and new concepts for mobile work hubs. The resulting seductive imagery of the ideal workspace is an exercise in brand development pastiche rendered as pseudo video game.

Time & Motion also stages a co-working space, developed by the RCA CX team, which weaves together venue, audience, workspace and digital space – presenting the entrance space of the gallery space into a live research ‘lab’. Visitors are encouraged to participate in the research, interaction and interventions, and workshops, salon discussions, and hacking and making sessions are woven into the experimental fabric of the exhibition.

The ‘CX Co-Working Space’ features three design interventions. The first, Hybrid Lives, features video work by Karen Ingham and an interactive installation responding to data traffic, dressed with ‘co-working furniture’. Where Do You Go To? is a wall-mounted moving freize showing the output from an app, co-designed with a group from the BBC, with the mission to connect remote workers through exchanging, Snap-chat-like (pre-hack) images of desks and workspaces. According to Ben Dalton, one of the main developers, this sharing of ‘desk context’ helps form a synergy of ‘headspace’ between remote workers.

Taking its cue from Frances Cairncross’s 1995 “The Death of Distance”, where the compelling vision that, over time, the communications revolution would release us from geographic locations, the project illustrates how digital space has redefined our working lives. However, for all its good intentions, this gesture towards remote solidarity seems to be muddying the new principles and rhythms of work with Taylorist and later Fordist ideals of panoptic surveillance and somehow stands in direct opposition to the emancipatory rhetoric of convergence culture.

Time and Motion focuses primarily on a particular demographic of labourer (generally the global information worker), and paints the picture of a tertiary lifestyle which involves multitasking without control over a narrative of time use, and habitual fractured thinking – where non-stop interactivity (a digital version of Taylorist motion) is crack cocaine for the drones. For this category of workers, the workplace is everyplace – diffuse, unfamiliar, a zone of insecurity. We are left with a “thin democracy” in which people are disengaged from political activity except when jolted into consciousness by a shocking event or celebrity meltdown witnessed virally on Youtube during office hours. As more work and labour takes place outside the pre-determined workplace – in the hybrid environments of cafes, trains and across the domestic landscape – the very idea of a work/life balance seems like an alien ideal to aspire to.In an open tertiary society, the industrial model of time, and the bureaucratic time management of factories and office blocks, breaks down. There is no stable time structure and we are increasingly losing our grip on our own time. Time and Motion at FACT interrogates the impact of this fragmentation on the aesthetic forms of contemporary art, and contemplates how artists might offer a critique of our neo-Taylorist predicament.

Read and learn how to solve a Rubiks Cube with the layer-by-layer method. It can be learned in an hour.

Featured image: Journey to Ard al Amal (The Land of Hope). Screenshot box & video installation. Impakt festival & exhibition. Image Pieter Kers

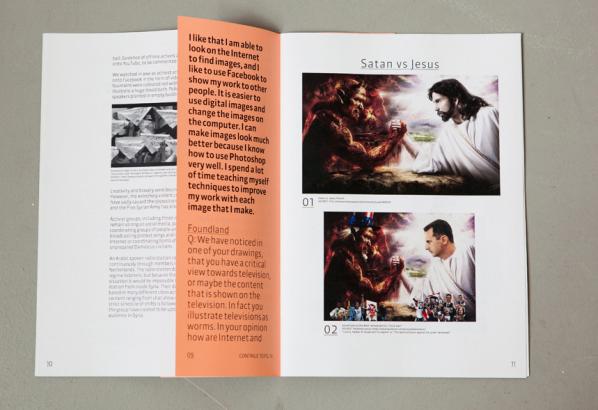

Foundland, Ghalia Elsrakbi (SY) and Lauren Alexander (SA), is a multi-disciplinary art and design practice based in Amsterdam. With backgrounds in graphic design, art and writing Foundland’s approach focuses on research based, critical responses to current issues. While moving around in advertising, printed matter, the Internet, and off line art spaces they dig up interesting stories about Disney, SpongeBob and defected soldiers.

Annet Dekker: Where does the name Foundland come from, or what does it mean?

Lauren Alexander: We started working together in 2009 and at the time we had worked on a project about being stateless, so Foundland seemed fitting. It is quite literally a way of thinking about how to found a land and to create a space that we could use as a platform for thinking about ideas with some kind of visual output. For us, space is related to political scenarios, and also to something virtual, online, all these different places that we inhabit.

Ghalia Elsrakbi: Foundland relates also to finding and discovering something new, looking behind something. We are very interested in speculation, we speculate about images and their meaning, in order to find something unexpected.

AD: What is your focus, what are you trying to find and tell?

LA: We want to tell stories in new ways, because by telling a story in a different way, especially related to subjects which are often seen in the media, you are offering an alternative perspective.

GE: The exhibition we just did for Impakt festival is a good example. With the installation Journey to Ard al Amal (The Land of Hope) we speculated how popular characters and animations, dubbed from Japanese to Arabic, or adapted from Walt Disney, play a valuable role in imagining heroes and villains. We were looking at a history of cartoons. This isn’t obviously political, but when seeing how cartoons are used in Syria and other places, interesting issues came up and we constructed a story that reflected on the current situation. We looked for connections between the way people see cartoon characters now and how they are embedded in childhood memories. In the end what we present is a kind of imagined picture of how things could be, maybe as an alternative to watching the news.

AD: Can you elaborate a bit, what images did you see and how did you (re)use them?

LA: In the installation we focused on this specific case study of the apocalypse scenario which is sketched in a cartoon series called Adnan and Leena in Arabic. In an earlier research essay Simba, the last Prince of Ba’ath country, we extracted images and characters from Arabic websites and speculate on appropriation by showing original images, before they were photoshopped. In a talk we did, we were also drawing connections to the way that Western cartoon characters are suddenly popping up in news footage, and how activists use cartoon identities on the Internet.

GE: Currently there is a full swing of the way Western stories are adapted. For example images of Mickey Mouse or SpongeBob are painted on walls in Syria. In the talk we question whether it is still Mickey Mouse that we see, the one that we remember from our children books, or if it means something else? We compared and related these images to the way such iconography is appropriated and used by both activists and ruling parties. The reuse of symbols and images and how sometimes historical moments are turned into something completely different is very interesting. Such findings are what we are really focusing on.

AD: There is also a long and popular tradition of autonomous animation in middle east, how does that relate to what you’ve been researching?

LA: Cartoons are very differently perceived in Syria, and also in South Africa, unlike in the Netherlands, they pose a huge threat to those in charge. For example the government is continuously suing political cartoonists like Ali Farzat in Syria and Zapiro in South Africa because their cartoons undermine existing power structures.

GE: There are indeed many artists who create political cartoons or satirical statements but with these Disney cartoons it was about finding the hidden story of an image. We recognise the cartoons from a Western perspective and the local one. By making connections and telling a different story we want to give a different perspective and a better understanding of what is really happening. Actually I grew up with Japanese Manga, but today Disney is everywhere. This is also political because in the time that Hafez Al-Assad was running Syria there was no American culture at all, when he died his son opened the country a bit for the Western market and you started to see American programmes. Nevertheless, everything is dubbed to Arabic so children don’t necessarily view it as an American production because it speaks their own language and sometimes stories and words are changed in order to better relate to Arabic countries.

LA: The connection to America is not obvious, what we found is that characters like SpongeBob and Mickey Mouse are simply friendly characters. They are your buddy, they help and like you.

GE: That is why they are used in this process of freedom fighting. ‘Your friends’ carrying the freedom flag and are used to create a kind of identification with the message that they want you to see. I mean, it is difficult to hate or not to trust these images because they are icons of friendliness. Whereas the image of a politician or some other hero who is telling a personal story can easily be damaged, a cartoon image is unbreakable. It appeals to children involved in the revolution. So, these images consist of many layers and bring up interesting questions. We aren’t looking for the true answer, because in the end we create our own story.

AD: Could you speak of a sort of universal populism or at least a continuing iconography?

GE: There are many different images, from the Lion and the Father and the Son, to things you see in public space, or images that people grew up with. These are all reused in a digital form and become part of the revolution. People tend to think of them as new images, but when you compare them to older ones, the original, it reflects very much the ideology of the regime. By putting them in a different context we try to force people to question the images and the stories.

LA: I remember that I was in South Africa when we were working on the fiction interview with a propaganda makers text and I had asked my mother to read it. She commented that ‘This is what the government used to say during apartheid, I recognize this’. I guess this shows quite a universal context. We are so used to advertisement and iconography that we don’t question it and tend to ignore the meaning.

GE: Yes, it’s not so different at all, propaganda still uses the same techniques, they have not changed and people fall for it. I think it’s very good to expose propaganda makers.

AD: What new context are you giving it?

LA: Up till now our work has been presented in a western context within the framework of festivals or art spaces.

GE: We wanted to show it to a Western audience, but now we also want to see how it will work when we go to Syria or the Middle East. This will be a challenge because we need to find a way to make that translation back again. We tried already a few times to publish texts for example, but the expectation is very different, stories are more direct and literal, you say exactly what you mean, not the way that we do it here which is reading between the lines.

AD: Is that also why you work in so many ways, from installations, to print, to presentation, to video?

LA: Yes, a lot of this is about experimentation with how things work. We often start from something that we have found online. We find a lot of information, which can be confusing, and then it is about finding the right moment, time and place to present it. Giving it all your attention to dig into an issue, know more and tell more.

GE: Each time we try to define the best way to present what we want to say. It is interesting to open and use the whole research process, it is not just about an end result that is presented. For example, now we are collecting a lot of defection movies from soldiers who are leaving the official army Syrian and joining the free army. What we notice is that the visibility of this free army is that it is only online, on YouTube. We are interested in how an identity of an army that exists on the ground and performs all kinds of operations, primarily takes place on YouTube. The videos of the defectors are almost like a physical performance of defection. We want to collect the story of it, to help people appreciate this image, why it was made, and think about what this means for us.

AD: Digging up memories and confronting people?

GE: When we started the cartoon project we noticed that people were hiding their identity online behind popular cartoon masks. It was really about how people used the Internet.

LA: We discovered that using the Internet is not always about the technical functions of connectivity, distribution, uploading and liking.

GE: If you look for example at how Syrians use the Internet, it’s really for emotional support. A few months ago there was no Internet in the whole of Syria, which was emotionally a big thing because people abroad couldn’t connect to people online and read their contributions. The revolution is nothing without these contacts. All of a sudden a Facebook campaign started called ‘Here is Damascus’. At first I didn’t understand it, but it turned out to be a reference to an event that happened in the 60’s in Cairo, while at war with Israel, the radios were cut off and there was no communication in the city. At that point the city of Damascus changed the name of their radio to ‘Cairo radio’. A political statement, like a re-enactment, happened now on Facebook. The Internet has all these different kinds of layers, of reflecting on history and bringing events to life.

See more Foundland work and updates at www.foundland.info