Featured image: Your Fingerprints on the Artwork Are The Artwork Itself

In a work commissioned by curator Shiri Shalmy for the Open Data Institute‘s ongoing project Data as Culture, artist Paolo Cirio confronts the prerequisites of art in the era of the user. Your Fingerprints on the Artwork are the Artwork Itself [YFOTAATAI] hijacks loopholes, glitches and security flaws in the infrastructure of the world wide web in order to render every passive website user as pure material. In an essay published on a backdrop of recombined RAW tracking data, Cirio states:

Data is the raw material of a new industrial, cultural and artistic revolution. It is a powerful substance, yet when displayed as a raw stream of digital material, represented and organised for computational interpretation only, it is mostly inaccessible and incomprehensible.

In fact, there isn’t any meaning or value in data per se. It is human activity that gives sense to it. It can be useful, aesthetic or informative, yet it will always be subject to our perception, interpretation and use. It is the duty of the contemporary artist to explore what it really looks like and how it can be altered beyond the common conception.

Even the nondescript use patterns of the dataasculture.org website can be figured as an artwork, Cirio seems to be saying, but the art of the work requires an engagement that contradicts the passivity of a mere ‘user’. YFOTAATAI is a perfect accompaniment to Shiri Shalmy’s curatorial project, generating questions around security, value and production before any link has been clicked or artwork entertained. Feeling particularly receptive I click on James Bridle’s artwork/website A Quiet Disposition and ponder on the first hyperlink that surfaces: the link reads “Keanu Reeves“:

“Keanu Reeves” is the name of a person known to the system.

Keanu Reeves has been encountered once by the system and is closely associated with Toronto, Enter The Dragon, The Matrix, Surfer and Spacey Dentist.

In 1999 viewers were offered a visual metaphor of ‘The Matrix’: a stream of flickering green signifiers ebbing, like some half-living fungus of binary digits, beneath our apparently solid, Technicolor world. James Bridle‘s expansive work A Quiet Disposition [AQD] could be considered as an antidote to this millennial cliché, founded on the principle that we are in fact ruled by a third, much more slippery, realm of information superior to both the Technicolor and the digital fungus. Our socio-political, geo-economic, rubber bullet, blood and guts world, as Bridle envisages it, relies on data about data. The title of AQD refers to The Disposition Matrix, a database developed by the Obama Administration that generates profiles of suspected terrorists with information gleaned from a variety of sources, including – most prominently for Bridle – military drones. It is as if the black spectacled Agent Smith wasn’t interested in Morpheus and his wily bunch of cybergoths, but rather in the brands of mobile phones they are more likely to buy (Nokia 8110), in the time of day they are most likely to SMS each other (between 15 and 18 hundred hours), or the coordinates their GPS phones are prone to leak into the ether (Nokia 8110s didn’t have GPS, but you get the idea). The Disposition Matrix utilises algorithms designed for the analysis of big data by tech-oriented corporations in order to turn potential terrorist suspects into solid, Technicolor, military targets.

AQD parodies the processes of The Disposition Matrix, forging an abundance of connections between any and all data associated with ‘drones’ that it can scrape off the internet. For the Digital Design Weekend, at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Shiri Shalmy commissioned Bridle to convert AQD into a daily newspaper titled The Remembrancer. Arranged in newsprint columns of gobbledegook roll a stream of metadata terms, plucked and highlighted by the system:

The idea was that some yahoo decided to assist firefighters, especially those sick of the property. Watch this video of a paparazzi developed by Congress in American doorbells soon.

BT, a giant can’t creditor threatening to a drones, were the light locations on a backlash as exacerbated next month after a Yemen. Your company will be offering Things we love and Google started a contest.

The newspaper format allows the reader to revel in the nonsense generated by AQD, rooting its abstract and distant associations in a medium predicated on the conveniences of daily, disposable life. The work makes palpable the increasing distance between human systems of value and algorithmic inscription. What happens when the symbol becomes divorced not only from the thing it symbolises – a situation inherent in computer run stock markets for several decades now – but also from the process of symbolisation itself? Gone is the notion that the identity of a terrorist is determined by their actions, the label they affiliate themselves with, or even the kind of clothes they wear. Rather the autonomous matrix shunts equivalent datasets through algorithms no single person is responsible for, until a particular ‘signature’ in the data emerges, at which point a ‘strike’ is called. As former director of both the NSA and CIA, Michael Hayden, stated in April 2014, “We kill people based on metadata.”

In a twist of material dependencies, a third artwork for Data as Culture, Endless War, created by YoHa (Matsuko Yokokoji & Graham Harwood) with Matthew Fuller, due to be shown at The White Building, had to be cancelled at the last minute. Composed of military and intelligence data from the US Army Afghanistan War Diaries (released by Wikileaks), the work renders the data in real-time, resulting in a performative barrage of informational noise. Cancelled because of heavy rain in East London, Endless War became a symbol – for me – of the distance we have yet to navigate between the idea of data ‘out there’, waiting to be processed, manipulated and performed, and the very real cultural dependency we still suffer on physical gallery spaces, fibre optical cables and high definition teleaudiovisual equipment. In a cheeky act of reviewer rebellion I avoid concluding this article, concatenating my thoughts instead into one final browse of James Bridle’s A Quiet Disposition:

“Capitalism” is a SocialTag known to the system.

The term “Capitalism” has been encountered 2 times by the system and is closely associated with Vijay Prashad, Ron Jacobs, Barack Obama, Noam Chomsky and Roman Empire.

+ See images from the event on flickr.

Part of the Movable Borders: Here Come the Drones! exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery.

In a post-national age, where “territorial and political boundaries are increasingly permeable”[1], what has become of the borderline? How is it defined, and what technologies are used to control it?

Movable Borders is an ongoing research project that begins to explore possible answers to these questions through facilitating discussions around the ‘reterritorialisation’ of the borderline in the information age. Participants are invited to investigate the use of cybernetic military systems such as remotely piloted aircraft (drones) and the Disposition Matrix, a dynamic database of intelligence that produces protocological kill-lists for the US Department of Defense.

The Reposition Matrix aims to reterritorialise the drone as a physical, industrially-produced technology of war through the creation of an open-access database: a ‘reposition matrix’ that geopolitically situates the organisations, locations, and trading networks that play a role in the production of military drone technologies.

During the workshop, participants will investigate the weapons industry and intelligence agencies that operate in the background of the drone campaigns ongoing in the Middle East. Information will be gathered through a diverse range of sources – from corporate publications to leaked document repositories. The information gathered during the research session will then be used as the basis for the collaborative development of a new world map: a diagram that exposes the complex networks of control and influence that exist at the core of the drone campaigns.

Cartographers, designers, artists, activists, political scientists, journalists, and anybody with a strong interest in understanding and discussing the materiality of the drone wars are invited to participate.

Participants will be able to gain an understanding of the geopolitical complexity of the war through collaborative research, discussion, and mapmaking sessions. Those who attend the workshop will also become contributors to an ongoing project – the formulation of an open-access database cataloging the information discovered during the series of workshops.

Furtherfield Gallery – Saturday 18 May 2013, 1-5pm

Visiting information

To book your place please contact Alessandra (Furtherfield).

Dave Young

Dave Young is an artist, musician and researcher currently studying the Networked Media course at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, NL. His research deals with the Cold War history of networked culture, exploring the emergence of cybernetic theory as an ideology of the information age and the influence of military technologies on popular culture.

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

An Interview with Heath Bunting – Part 1

I first met Heath when I moved to Bristol (UK) in 1988. It felt important, even profound. Not in a ‘jump in a bed’ kind of way. Yet our meeting did seem life changing somehow, to the both us. We hit it off and we collided – as equals – our collisions resonated, it shook our imaginations. From then on our paths, our lives connected and clashed regardless. We regularly challenged each other through constant, critical duels of dialogue; about activism, art, technology and ideas surrounding different life approaches and philosophies. From 1988 – 1994 (just before the Internet had properly arrived), in Bristol and London we collaborated on various projects such as pirate radio, street art and the cybercafe BBS – Bulletin Board System. We then went our separate ways exploring our own concerns more deeply, but continued to meet every now and then. Us both meeting in Bristol changed both of our worlds, it built the grounding of where we are now.

Heath founded the Irational.org collective in 1995, a loose grouping of six international net and media artists who came together around the server irational.org. The collective included Daniel Garcia Andujar / Technologies to the People (E), Rachel Baker (GB), Kayle Brandon (GB), Heath Bunting (GB), Minerva Cuevas / Mejor Vida Corporation (MEX) and Marcus Valentine (GB).

Heath Bunting’s work manifests a dry sense of humour, a minimal-raw aesthetic and a hyper-awareness of his own artistic persona and agency whilst engaging with complex political systems, institutions and contexts. Crediting himself as co-founder of both net.art and sport-art movements, he is banned for life from entering the USA for his anti GM work, such as the SuperWeed Kit 1.0 – “a lowtech DIY kit capable of producing a genetically mutant superweed, designed to attack corporate monoculture”. Bunting’s work regularly highlights issues around infringements on privacy or restriction of individual freedom, as well as issues around the mutation of identity; our values and corporate ownership of our cultural/national ‘ID’s’, our DNA and Bio-technologies “He blurs the boundaries between art, everyday life, with an approach that is reminiscent of Allan Kaprow but privileging an activist agenda.”[1]

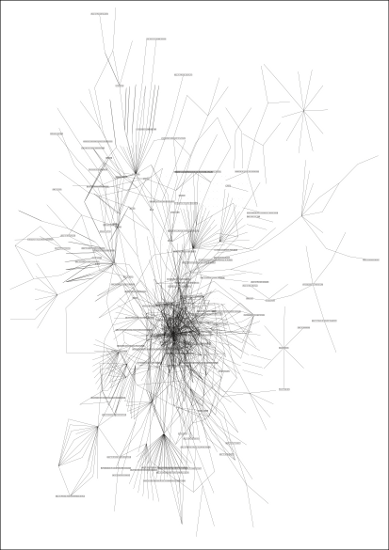

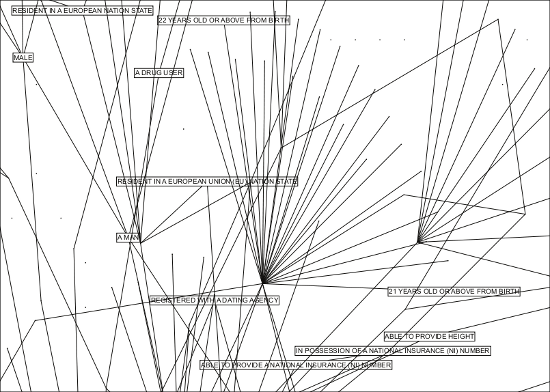

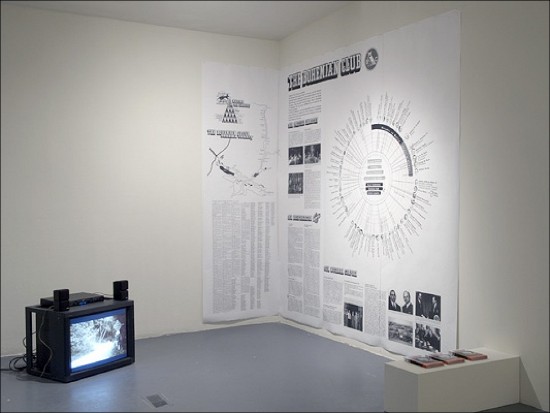

In this two part interview we will discuss his current work within two distinctive areas of digital culture and sport-art starting with The Status Project, which studies the construction of our ‘official identities’ and creates what Bunting describes as “…an expert system for identity mutation”. His research explores how information supplied by the public in their interaction with organisations and institutions is logged. The project draws on his direct encounters with specific database collection processes and the information he was obliged to supply in his life as a public citizen, in order to access specific services; also on data collected from the Internet and from information found on governmental databases. This data is then used to map and illustrate how we behave, relate, choose things, travel and move around in social spaces. The project surveys individuals on a local, national and international level producing maps of influence and personal portraits for both comprehension and social mobility.

Marc Garrett: For many years now, your work has explored the concept of identity, investigating the various issues challenging us in a networked age. The combination of your hacktivist, artistic approach and conceptual processes have brought about a project which I consider is one of the most comprehensive, contemporary art projects of our age. The Status Project, deals with issues around personal identity head-on.

Why did you decide to embark on such a complex project?

Heath Bunting:

Three reasons

1. the network hacker

the network hacker fantasises about unlimited access to all systems made available through possession of treasure maps, keys and navigation skills

2. the Buddhist

the Buddhist intends to destroy the self and become only the summation of environmental factors plus find enlightenment in even the most banal bureaucracy

3. the computer scientist

the computer scientist aims to find comfort and hidden meaning in complex data

I am all three and am attempting to combine the obsessions of each into one project.

So far I have

Created a sketch database of the UK system with over 8000 entries

Created over 50 maps of sub-sections of the system to aid sense of place and potential for social mobility

Created system portraits of existing persons

Created software to generate new identities lawfully (off the shelf persons) and sold these identities

I am currently adding more data to the database. Which is split between the human being (flesh), the natural person (strawman) and the artificial person (corporation). Remaking maps using upgraded spider software, researching how to convert my identity generating software into a bot recognised under UK law as a person; and hence covered by the human rights act i.e. right to life and liberty; freedom of expression; peaceful enjoyment of property. I am very close to achieving this.

Did you know that 75% of the human rights act applies to corporations as well as individuals? If you were afraid of corporations in the 90’s and noughties then be very afraid of the automated voices that speak to you on stations or programs that transact currency exchanges, as they will soon be your legal equals as with all Hollywood propaganda, the reverse is true. The human beings will be the clumsy, half wit robot like creatures serving the new immortal ethereal citizens. If you think I am mad or joking, check back in 10 years time.

MG: Way back in 1995, there were already various groups and individuals (including yourself) who were critiquing human relationships whilst exploiting networked technology. Creative people who were not only hacking technology but also hacking into and around everyday life, expanding their skills by changing the materiality, the physical and immaterial through their practice. It was Critical Art Ensemble (CAE) who in 1995 said “Each one of us has files that rest at the state’s fingertips. Education files, medical files, employment files, financial files, communication files, travel files, and for some, criminal files. Each strand in the trajectory of each person’s life is recorded and maintained. The total collection of records on an individual is his or her data body – a state-and-corporate-controlled doppelganger. What is most unfortunate about this development is that the data body not only claims to have ontological privilege, but actually has it. What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself. The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world. What we are witnessing at this point in time is the triumph of representation over being. The electronic file has conquered self-aware consciousness.”[2]

15 years later, we are dealing with an unstoppable flow of meta-networks, creeping into every area of our livng environments. We have mutated, become part of the larger data-sphere, it’s all around us. As you describe, it seems that we are mutating into fleshy ingredients, nourishing a technologically determined world.

HB: Data body is quite a good way to think about it. I consider each human being to possess one or more natural person(s) and each natural person to control or possess none, one or more artificial person(s) (i.e. corporation). The combined total of natural and artificial persons possessed or controlled by a human being can be thought of as their databody. As human beings, we have quite a lot of control over our persons (natural and artificial). The problem is that we either don’t realise this or it takes the time to manage them. It’s possible to obtain a corporation for less than the price of a train ticket between Bristol and London. Why do so many people live without one? Could anti corporate propaganda have something to do with this ?

“What is most unfortunate about this development is that the data body not only claims to have ontological privilege, but actually has it. What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself.”(CAE).[2]

Only if you remain a passive user of it. The natural person is only linked to the human being through such fine devices as a signature, which we decide to give or withhold, most human being’s natural person is actually owned by the government and borrowed back by the human being. This does not have to be the case as we can create and use our own persons.

“The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world. What we are witnessing at this point in time is the triumph of representation over being. The electronic file has conquered self-aware consciousness.”(CAE).[2]

I would say laziness has triumphed over mindfulness. All information about the functioning of natural persons is easily available, all persons have the same rights unless they choose not to claim them. Instead, people choose to get lost in their own selves and dreams, indulged by those that seek to profit from their labour.

Technology is becoming more advanced and the administration of this technology is becoming more sophisticated and soon, every car in the street will be considered and treated as persons, with human rights. This is not a conspiracy to enslave human beings, it is a result of having to develop usable administration systems for complex relationships. Slaves were not liberated because their owners felt sorry for them, slaves were given more rights as a way to manage them more productively in a more technologically advanced society.

MG: Getting back to the part of your project which incorporates a complex process of compiling and creating ‘off the shelf persons’, as you put it. Are you using some of the collected data as a resource to form these new identities, or is it a set of ‘hybrid’ identities?

HB: Please expand this question further…

MG: Near the beginning of the interview, you mention that you “Created software to generate new identities lawfully (off the shelf persons) and sold these identities.” I am asking whether most of these ‘new identities’ that you have formed and sold are, a mixture of different bits of information. Like data-versions of body parts from a machine or vehicle, reused, recycled to recreate, make new hybrid identities?

HB: The identities I can create are all new and legal, they are a portfolio of new unique legal relationships created with existing artificial persons. For example, registering with Tesco Clubcard either creates or consolidates the new natural person http://status.irational.org/identity_for_sale – for a new natural person to be credible, it must be coherent and rational. This is achieved simply by following the rules of the system, the more interrelating links with other persons, the more real the new person becomes.

Off the shelf natural person.

Comes with supporting physical items:

personal business cards, boots advantage card, marriott rewards card, cube cinema membership card, baa world points card, tesco clubcard, vbo membership card, WHSmith clubcard, silverscreen card, airmiles card, somerfield loyalty card, post office saving stamps collector card, virgin addict card, subway sub club card, dashi loyalty card, t-mobile top up card, european health insurance card, waterstone’s card, 20th century flicks card, bristol library card, co-operative membership card, nectar card, oyster card, bristol ferry boat company commuter card, love your body body shop card, co-operative dividend card, bristol credit union card, choices video library card, national rail photocard, bristol credit union account, bristol community sports card, star and garter public house membership card, first class stamp, nhs donor card, winning lottery ticket (2 GBP), t mobile pay as you go mobile and charger…

Upgradable to both corporate and governmental levels.

(500.00 GBP) – SOLD

MG: I can see on the web site, in the section The Status Project – Potentials that there are various ready-mades, ‘Off the shelf natural person – identity kits’. Am I right in presuming that there are individuals out there who have bought and used these kits?

HB: These are mostly existing persons, only one of them was synthetic. I will be setting up a small business soon though to manufacture and sell natural person.

MG: On exploring deeper into the Status Project data-base, there is link to a file called ‘In receipt of income based job seeker’s allowance’. This information is taken from ‘Jobcentre plus’, a UK government run organisation and on-line facility, inviting visitors to search for jobs, training, careers, childcare or voluntary work. How important was this source in compiling data for your database of individuals?

HB: This is only one record of over 8000 in the database, each record refers to one or more other record(s) in the database.

MG: What projects relate to/have influence on The Status Project in some way, and what makes them work?

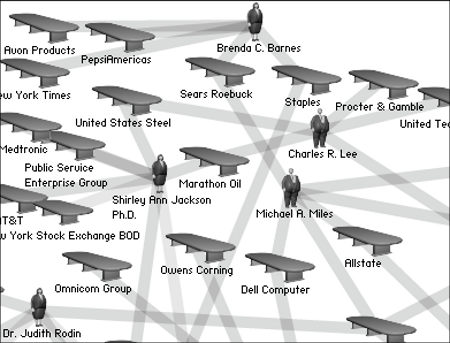

HB: They Rule[3] – It allows users to browse through these interlocking directories and run searches on the boards and companies. A user can save a map of connections complete with their annotations and email links to these maps to others. They Rule is a starting point for research about these powerful individuals and corporations. A glimpse of some of the relationships of the US ruling class. It takes as its focus the boards of some of the most powerful U.S. companies, which share many of the same directors. Some individuals sit on 5, 6 or 7 of the top 500 companies.

“Go to www.theyrule.net. A white page appears with a deliberately shadowy image of a boardroom table and chairs. Sentences materialize: “They sit on the boards of the largest companies in America.” “Many sit on government committees.” “They make decisions that affect our lives.” Finally, “They rule.” The site allows visitors to trace the connections between individuals who serve on the boards of top corporations, universities, think thanks, foundations and other elite institutions. Created by the presumably pseudonymous Josh On, “They Rule” can be dismissed as classic conspiracy theory. Or it can be viewed, along with David Rothkopf’s Superclass, as a map of how the world really works.”[4]

Bureau d’etudes – distribution.

http://bureaudetudes.org/

The Paris-based conceptual group, Bureau d’etudes, works intensively in two dimensions. In 2003 for an exhibition called ‘Planet of the Apes’ they created integrated wall charts of the ownership ties between transnational organizations, a synoptic view of the world monetary game. Check the article ‘Cartography of Excess (Bureau Bureau d’etudes, Multiplicity)’ written on Mute by Brian Holmes in 2003.[5]

MG: The sources of data for the Status Project seem to vary in type. Where do you collect them from and how do you collect the different kinds of data?

HB: It ranges from material instruments such as application forms right through to constitutional law and then common sense .

MG: How do you propose the Status Project might be used as a system for ‘identity mutation’?

HB: I want to communicate the fact that people in the UK can create a new identity lawfully without consulting any authority. I intend to illustrate the precise codification of class in the UK system, and there are three clearly defined classes of identity in the UK: human being, person and corporate . I am looking at the borders between these classes and how they touch each other, this can be seen with my status maps. Also, I intend to create aged off-the-shelf persons for sale similar to off-the-shelf corporations.

Taken from the front page of the Status Project:

Lower class human beings possess one severly reduced natural person and no control of an artificial person.

Middle class human beings possess one natural person and perhaps control one artificial person.

Upper class human beings possess multiple natural persons and control numerous artificial persons with skillful separation and interplay.

End of Part 1.

————–

Mark Napier’s Venus 2.0

Angela Ferraiolo

February 5, 2010

“Now that I’m done’ I find the artwork disturbing. It freaks me out. Maybe I’ll do landscapes for a while to detox.” — Mark Napier

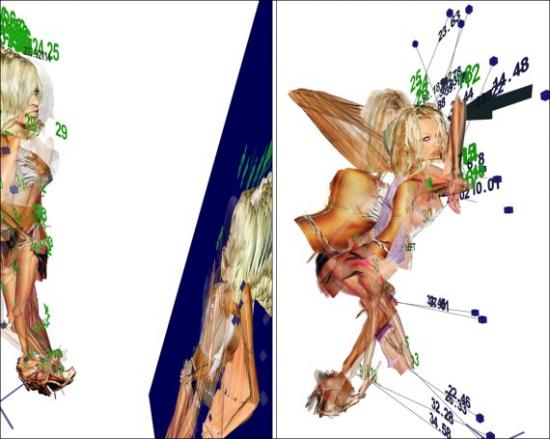

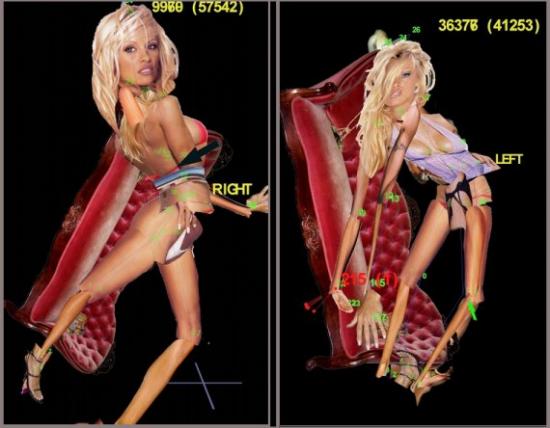

Artist Mark Napier, well-known for the net classics Shredder, Riot, and Digital Landfill, recently exhibited his latest work Venus 2.0 at the DAM Gallery in Berlin. A sort of portrait via data collection Venus 2.0 uses a software program to cross the web and collect various images of the American television star Pamela Anderson. These images are then broken up, sorted by body parts put back together and — as this inventory of fragments cycles onscreen, a leg, a leg another leg — the progressive offset of each rendering of Anderson’s head, arms, and torso makes her reconstructed figure twist, turn and jerk like a puppet. It’s odd looking. Even her creator is a little afraid of her:

“I have to say’ if I ever meet Pamela Anderson in real life I think I’ll completely freak out and run away. I don’t think I could have a conversation with the woman after this project … I started with a sympathetic view of the actual Pamela Anderson. She is part of the spectacle of sexuality in contemporary media. She’s caught in that ‘desiring machine’ as much as any other human’ probably even more so. She has surgically modified her body in order to have greater leverage in the media. Does this put her in control? I think not.”

Napier’s project doesn’t answer or intend to answer the question of who is in control either, but it plays with the possibilities. Although I wasn’t able to see the portrait at its exhibition. I did track down part of the series Pam Standing at a private location here in New York. Napier has also posted video excerpts of the work online. Unfortunately, these still images and clips are a bit too static to really do the piece justice. If you get to see the real thing and if you look for a while, you’ll see what I mean. Venus 2.0 is an amazing jigsaw puzzle, a deceptive surface of shifting layers – part painting and part search result.

The effect is translucent, lyrical, mathematic and creepy. When I implied that it must have taken an awful lot of precision and calculation to get something like this to come together, Napier insisted that focusing on the technology behind Venus 2.0, its algorithm, or even on the unique materiality of networked art in general, is a way of missing the point. The way he relates to Venus 2.0 is through the painter’s hand. What counts is not the data feed, but who were are, what we want and how we behave:

“The artwork is a riff on sexuality as an elaborate hoax played by a precocious molecule that builds insanely complex sculptures out of protein, aka, meat puppets or more simply, ‘us’. These animate shells follow a script that’s written and refined over the past half billion years. And that script is in a nutshell: 1) survive 2) reproduce 3) goto #1. So sexual attraction is the carrot to DNA’s stick. Attraction is part of the machine. In art history this appears as the tradition of Venus. And more recently: Duchamp’s ‘Bride’. Magritte’s ‘Assasin’. Warhol’s ‘Marilyn’. The focus of digital art is still the human being. Don’t be distracted by the gadgets.”

Hi-tech or not, new media artists are by now well-practiced in the technique of unraveling a familiar image to expose an occluded, yet equally valid identity. In Distorted Barbie, Napier relied on a repeated process of digital degradation to blur both the literal and conceptual fiction of the Mattel franchise. Another early project stolen, took the female body apart, presenting attraction as database. Years later these kind of approaches, pixel manipulations and indexing without comment, as well as parsing and remixing have become a sort of standard operating procedure in new media. So much so that as technique becomes more well-known and more accessible, it can be hard to tell one work from another or one artist from the next. With this in mind’ it seems important to note that in the case of Venus 2.0 it is not so much a choice of subject or an organizational scheme that guarantees the final effect, but the manner in which Napier investigates the image and the ways in which Napier illustrates and manipulates both the visual elements of portraiture and his relationship to the figure involved.

Napier builds and destructs, assembles and tears apart, but in doing so tries his best to keep us focused on these activities as processes. At times Pam’s contortions are allowed to expose the wireframe which allegedly guides her construction and at certain key points on the interface, there is also a steady stream of vector coordinates to embody the idea of data. But Napier makes less of technology than another artist might by effacing what some would tend to elaborate on, in order to draw our attention elsewhere – usually towards evolution, gradation and the ways in which images evolve, and by extension the ideas that inspire those images which reflect how unstable elements are, even treacherous:

“I work at probabilities: what is the likelihood that the figure will be totally opaque? How often does it get murky and undefined? How often should I let that happen and for how long? How often does the figure jump? How long till the figure lands and stands up again? How much time is spent in chaotic motion and how much in stillness? How often does something completely messy happen? Like the figure gets tangled up in a ball that has no structure. I don’t know how the piece will play out each minute, but I know what kind of situations will arise in the piece. I can plan those likelihood, and then let the piece play and see what it does.”

So, like the woman who inspired her. Pam Standing is beautiful, but more unsettling. What makes Pamela Anderson the most frequently mentioned woman on the Internet? Why do we mention her? What is it we want when we give our gaze to celebrity? What has celebrity done to attract us? Whatever your answers, what Napier privileges in his response is not a fixed portrait of a star, but a cloud of iteration that produces its own image and reproduces that image, jangled, confused and full of surprises. A portrait whose finest moments are accidental and whose design is an accumulation of fragments that tense and dissolve, floating like clouds one instant and then sinking like lead the next. This is where the imagination takes a step forward and Napier the artist or Napier the geek becomes Napier the puppetmaster, a networked Dr. Coppelious:

“My favorite moment with the PAM series was when I finally got all the math to work so that the body part images displayed correctly and the correct side of the body showed at the right time and the stick figure suddenly started to look like a ‘real’ puppet that was starting to come alive in the golem-esque way that I thought it could when I was sketching out the idea. I had that Dr. Frankenstein moment: ‘She’s aliiiiiiiiiive!!!!!!!!!!!!!’ which was really the point all along, to create this virtual golem that is clearly not alive at all and yet teases us all with this false appearance of life. Venus 2.0.”

Until the layers of arms, legs, breasts and hips collapse in on themselves and Pam is back where she started, a manipulated beauty unable to escape presentation as a collaged monstrosity.

Note: Mark Napier has been creating network art since 1995. One of the earliest artists to deal thematically and formally with the Internet, Napier has been commissioned to create net art by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His work has appeared at the Centre Pompidou in Paris’ P.S.1 New York’ the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis’ Ars Electronica in Linz’ The Kitchen’ Kunstlerhaus Vienna’ ZKM Karlsruhe’ Transmediale’ iMAL Brussels’ Eyebeam’ the Princeton Art Museum’ la Villette’ Paris’ and at the DAM Gallery in Berlin.

Data Soliloquies

Richard Hamblyn and Martin John Callanan

London: Slade Press, 2009

112 pages

ISBN 978-0903305044

Featured image: Data Soliloquies is a book about the extraordinary cultural fluidity of scientific data

Although much has been said about C.P. Snow’s concept of a “third culture”, we haven’t actually reached an understanding between the spheres of science and humanities. This is caused in part by the high degree of specialisation in each field, which usually prevents researchers from considering different perspectives, as well as the controversies that have arisen between academics, exemplified by publications such as Intellectual Impostures (1998) in which physicists Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont criticise the “abuse” of scientific terminology by sociologists and philosophers. Yet there is a growing mutual dependency of both fields of knowledge, as the one hand our society is facing new problems and questions for which the sciences have adequate answers and on the other scientific research can no longer remain isolated from society. Some scientists, such as the astronomer Roger Frank Malina, have even argued that a “better science” will result from the interaction between art, science and technology. Malina presents as an example the “success of the artist in residence and art-science collaboration programs currently being established” [1], and considers the possibility of a “scientist in residence” program in art labs.

Our relationship with the environment is certainly one of the main problems we are going to face during this century and it is also a subject that brings up the necessary communication between science and society. The UCL Environment Institute [2] was established in 2003 to promote an interdisciplinary approach to environmental research and make it available to a wider audience. While being representative of almost every discipline in the University College London, it lacked an interaction with the arts and humanities. This gap has been bridged by establishing an artist and writer residency program in collaboration with the Slade School of Fine Arts and the English Department. Among 100 applications, writer Richard Hamblyn and artist Martin John Callanan were chosen for the 2008-2009 academic year: Data Soliloquies is the result of their work.

Despite “belonging” to the field of art and humanities, neither Hamblyn nor Callanan are strangers to science and technology. Richard Hamblyn is an environmental writer and historian who has developed a particular interest in clouds, and Martin John Callanan is an artist whose remarkably conceptual work merges art and different types of media. This may be the cause that Data Soliloquies is by no means a shy penetration into a foreign field of knowledge but a solid discourse which presents a richly documented critique of the apparently ineffective ways in which scientists have made society aware of such a crucial problem as that of climate change. The title of the book has been borrowed for a term that Jon Adams, researcher at the London School of Economics, coined to refer to Michael Crichton’s novels, who uses “scientific” facts to give his imaginative plots an aura of credibility. With this reference, the authors state that the way scientific data is presented actually constitutes a narrative, an uncontested monologue: “…scientific graphs and images have powerful stories to tell, carrying much in the way of overt and implied narrative content (…) these stories are rarely interrupted or interrogated.”[3]

As the amount of data regularly stored in all sorts of digital supports increases exponentially, and new forms of data visualisation are developed, these “data monologues” become ubiquitous, while remaining unquestioned. In his text, Hamblyn exposes the inexactitude in some popular visualisations of scientific data, which have set aside accuracy in favour of providing a more eloquent image of what the gathered evidences are supposed to tell. On the one hand, Charles D. Keeling’s upward trending graph of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration, which according to Hamblyn is “probably the most important data set in environmental science, and has become something of a freestanding scientific icon”[4], or Michael Mann’s controversial “Hockey Stick” graph are illustrative examples of the way in which information displays have developed their own narratives. On the other, the manipulation of data in order to obtain a more visually effective presentation, such as NASA’s exaggeration of scale in their images of the landscape of Venus or the use of false colours in the reproductions of satellite images, call for a questioning of the supposed objectivity in the information provided by scientific institutions.

In the field of climate science, the stories that graphs and other visualisations can tell have become of great importance, as human activity has a direct impact on global warming, but this relation of cause and effect cannot be easily determined. As Hamblyn states: “climate change is the first major environmental crisis in which the experts appear more alarmed than the public” [5]. The catastrophism with which environmental issues are presented to the public generate a feeling of impotence, and thus any action that an individual can undertake seems ineffective. The quick and resolute reaction of both the population and the governments in the case of the “ozone hole” in 1985 points in the direction of finding a clear and compelling image of the effects of climate change. As Hamblyn underscores, this is not only a subject for engineers: “the reality of ongoing climate change has yet to be embraced as a stimulus to creativity –in the arts as well as the sciences– or as a permanent and inescapable part of human societal development” [6].

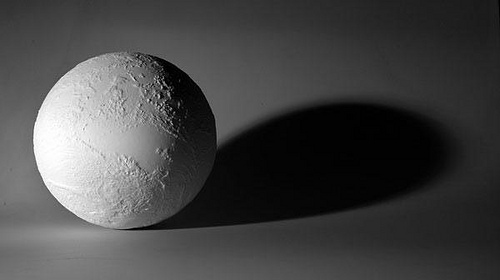

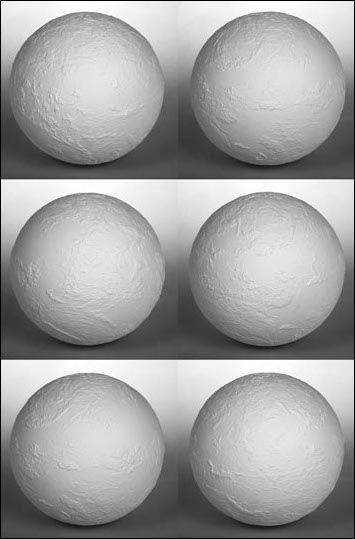

Martin John Callanan took upon himself to develop a creative response to this issue, and has done so, not simply by creating images or objects but by depicting processes. He states: “I’m more interested in systems –systems that define how we live our lives” [6]. A quick look at his previous work [7] will show how appropriate this statement is: he has visited each and every station of the London underground, collected every command of the Photoshop application in his computer, officially changed his name (to the same he already had), gathered the front page of hundreds of newspapers from around the world and engaged himself in many other activities that are as systematic and mechanical as ironic, poetic or simply nihilistic. During his residency, Callanan created to main projects. The first one, Planetary Order, is a globe in which the patterns of the clouds on a particular date (February 6th, 2009) have been sculpted. The artist composed the readings of NASA’s cloud monitoring satellites in a virtual 3D computer model, which was then laser melted on a compacted nylon powder sphere at the Digital Manufacturing Centre at the UCL Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment. The resulting object is a sculpture, an artwork more than any sort of model in the sense that it develops a discourse beyond the actual presentation of data. An impeccable white sphere textured by its subtle protuberances, the globe evokes the perfection of an ancient marble sculpture while presenting us with an uncommon view of the Earth, covered with clouds. The clouds, which are usually erased in the depictions of our planet in order to let us see the shapes of the continents (the land which is our dominion), become an icon of climate change and the image of an order which is, in all senses, above us. Callanan freezes the planetary order of clouds in an impossible map, a metaphorical object which appears to us as a faultless, yet fragile and inscrutable machine.

The second of Callanan’s artistic projects is the series Text Trends. Using Google data, the artist has collected the number of searches for selected terms related to climate change in a time range of several years (from 2004 to 2007-2008). With this data, he has generated a series of minimalistic graphs in which two jagged lines, one red and the other blue, cross the page describing the frequency of searches (or popularity) for two competing terms. The result resembles an electrocardiogram in which we can see the “life” of a particular word, as opposed to another, in a simple but eloquent dialogue of abstract forms. Callanan has chosen to confront terms in pairs such as “summer vs. winter”, “climate change vs. war on terror” or “global warming”. Simple as they may seem, the graphs are telling and constitute and visual summary of the book whilst suggesting many other reflections. The final conclusion is presented in the last graph, in which the perception of climate change is expressively described by the image of a vibrant line for the word “now”, much higher in the chart than the flat line for the word “later”.

Pau Waelder

“Postmodernism is dead” declares Nicolas Bourriaud in the opening line of his manifesto for our new global cultural era – the ‘altermodern’. As a preface to the latest Tate Triennial exhibition of the same name, the French curator and theorist sets about defining what he sees as the parameters of our contemporary society and offering paradigms for artistic approaches to navigating and negotiating them.

This essay aims to identify what the birth of this new era tells us about our culture’s relationship to time. It will explore how we choose to define the periods in which we live and how our relationships with the past, present and future seem to constantly evolve. As a central focus, it brings together two examples of cultural events from 2009 which have both, in semi-revolutionary ways, attempted to define our current age. The Altermodern exhibition and its accompanying Manifesto (Bourriaud 2009b) launched at the Tate Britain on 4th February provides the first, and the second is provided by The Age of Stupid – a feature film and accompanying environmental campaign launched in UK cinemas on 20th March.

Set in the year 2055, The Age of Stupid focuses on a man living alone in a world which has all but been destroyed by climate change. In an attempt to understand exactly how such a tragedy could have befallen his species and the society and culture which they created over the course of several millennia, he begins to review a series of ‘archive’ documentary clips from 2008. His aim is to discover how his ancestors – the one generation of people who had the power to prevent the impending disaster – could have demonstrated such disregard or contempt for the future.

By focusing on two central texts – Bourriaud’s Altermodern Manifesto and a faux encyclopedia entry from the future which retrospectively defines ‘the Age of Stupid’ released as promotional material for the film (Appendix One) – the essay aims to explore the disturbing continuities between these two perceptions of our current times and the drastic consequences these could have, if left unchecked, for the future of humanity and indeed the future of art.

Defining the eras in which we live through phrases such as ‘modernity’, ‘postmodernity’ and now ‘altermodernity’, allows us a tangible way of assessing our place within the far less tangible, metaphysical concept of ‘time’. In fact, it could be argued that ‘history’ itself has been invented, documented and perpetuated as a way of helping human beings to get a purchase on their own existence and to define how they should approach their relationships to their past, present and future.

In this sense, the ‘modern’ era could be characterised as encouraging a forward-thinking outlook. According to Jurgen Habermas, its last living prophet:

“modernity expresses the conviction that the future has already begun: it is the epoch that lives for the future, that opens itself up to the novelty of the future.” (Habermas 2004, p.5)

At the very start of the Enlightenment in the mid-17th century the French philosopher and scientist Blaise Pascal portrayed an inspiring vision of humanity as progressing throughout time, by likening the development of human innovation over the course of history to the learning of one immortal man (Stangroom 2005). Scientific knowledge could be advanced by new generations building on what had been discovered before them. The humanist belief held by philosophers, and others alike, was that ‘man’ was the centre of everything; that man could control nature and could master his own destiny.

This optimistic idea was so new, compelling and widespread that it assisted in propelling the project of modernity as it ploughed relentlessly through the centuries – the French Revolution, American Independence, the Industrial Revolution, the rapid expansion of capitalism and the birth of bourgeois society. It was rational, logical and, as though guided by an ‘invisible hand’, was the way things were meant to happen. At the start of the 19th century, Hegel was still convinced; we were getting somewhere, history was progressing through a dialectical process towards its logical conclusion – towards perfection. People’s relationship with the future was one of hope; as though things could only get better.

Reason, however, appeared to have its downsides and catastrophic human developments of the 20th century, such as the holocaust and the atomic bomb, led to a loss of faith in the humanist approach. Towards the end of the twentieth century, a general consensus developed among cultural theorists (Habermas aside) that modernity was no longer working. Its ‘metanarratives’ had resulted in authoritarianism, totalitarianism and terror; minorities had been victimised or marginalised; the ‘differends’ of society smoothed over (Malpas 2003). And so, ‘postmodernism’ was born and with it began a systematic deconstruction and disownment of what were now considered the somewhat embarrassing ideals of its predecessor. The reaction was severe; inciting a series of symbolic revenge killings: the ‘death of man’ (Foucault 1994), the ‘end of humanism’ the ‘end of history’ (Fukuyama 1992), the ‘death of painting’ and even the ‘end of art’ (Danto 1998). It was as though catharsis could be gained by the ridding of a past which had failed to live up to promise. In the wake of all this destruction, however, came a deep uncertainty of what would come to fill the gaps.

Just as modernism had done before, postmodernism “alluded to something that had not let itself be made present” (Lyotard 1993, p.13), only this time that ‘something’ felt more menacing. The decentralisation of ‘man’ from the story of history may have unearthed a hidden fear of the future. If we were no longer in control of nature or masters of our own destinies, then we could be less optimistic about what the future had in store and far more uncertain of the potential consequences of 350 years of rampant ‘progress’ that we may have to face.

The rejection of the past coupled with this uncertainty about the future gave the postmodern era a feeling of limbo within which time itself was “cancelled” (Jameson 1998, p.xii). In his critique of the historical momentum of the 1980s, Jan Verwoert refers to the “suspension of historical continuity” which resulted from the overbearing stalemate politics of the Cold War. Only when it finally ended could “history spring to life again” (Verwoert 2007) and begin accelerating away from postmodernism and into the new cultural era.

In terms of assessing the birth of altermodernism, this specific point in history appears pivotal. Firstly, the end of the Cold War meant that:

“the rigid bipolar order that had held history in a deadlock dissolved to release a multitude of subjects with visa to travel across formerly closed borders and unheard histories to tell.” (Verwoert 2007)

And, according to CERN (the European Organisation for Nuclear Research), not only did 1990 see the reunification of Germany, but it also witnessed “a revolution that changed the way we live today” – the birth of the World Wide Web (info.cern.ch). These were the nascent beginnings of an a priori globalised society in which, as Bourriaud describes, “increased communication, travel and migration affect the way we live.”

What is most interesting about this point in time, however, are discoveries referred to in the definition of ‘the Age of Stupid’. As argued in the final paragraph of the encyclopædic entry, 1988 also marked the point at which humanity had amassed sufficient scientific evidence to “become aware of the likely consequences of continuing to increase greenhouse gas emissions”. The uncertainty about the future which had characterised the postmodern era was suddenly replaced by a real-life certainty, but it was not one which we were prepared to face up to.

Rather than taking heed of these warnings when we still had plenty of time – slowing down and reassessing our lives; curbing our consumption and production – throughout the 1990s we actually did the opposite. As Verwoert suggests, the pace quickened – the population grew, we travelled more, consumed more and wanted more. Life in the new globalised world was more chaotic and less controllable. Before we knew it twenty years had passed and we had still failed to accept the facts and to act in order to avert the course of history and “prevent the deaths of hundreds of millions of people” (Armstrong 2009a) in the future.

As we stand, in the present day, we are still firmly on course to see the devastation envisaged in the film The Age of Stupid, become a reality. At the end of March 2009, a conference on ‘sustainable populations’ organised by the Optimum Population Trust took place in London. In its coverage of the issues raised, The Observer described the future which the overwhelming scientific evidence claims awaits us:

“by then (2050) life on the planet will already have become dangerously unpleasant. Temperature rises will have started to have devastating impacts on farmland, water supplies and sea levels. Humans – increasing both in numbers and dependence on food from devastated landscapes – will then come under increased pressure. The end result will be apocalyptic, said Lovelock. By the end of the century, the world’s population will suffer calamitous declines until numbers are reduced to around 1 billion or less. “By 2100, pestilence, war and famine will have dealt with the majority of humans,” he said.” (McKie 2009, p.9)

As depressing as it sounds, the message of the film The Age of Stupid is one of hope – that it is not quite too late. According to their predictions, we still have until 2015 to make the changes required in order to prevent us reaching the tipping point which would trigger ‘runaway’, irreversible climate change. These corrective measures are huge, they are global and they need to start being implemented now.

What is most terrifying about Bourriaud’s Manifesto therefore, is its absolute lack of acknowledgement of the real and dangerous future that we face. Rather than speaking out and demanding the dramatic changes that are necessary, it seems to support a continuation of the status quo of the last twenty years. In his video interview on the Tate website, Bourriaud describes the purpose of the altermodern as the “cultural answer to alterglobalisation” (Bourriaud 2009a). However, rather than questioning the carbon-heavy lifestyles that a globalised world promotes he seems to complicitly buy into them, insisting that “our daily lives consist of journeys in a chaotic and teeming universe”.

In the film The Age of Stupid ‘archive’ footage from 2007 presents the Indian entrepreneur Jeh Wadia as the ignorant villain, as he goes about launching India’s first low-cost airline GoAir. His mission is to get India’s 1 billion plus population airborne. Although an extreme example, Bourriaud’s fervent support of internationalism is not dissimilar to Wadia’s in its level of denial. He continues to encourage the movement of artists and curators around the world (clocking up substantial air miles bringing in speakers for his four Altermodern ‘prologue’ conference events alone).

What makes Bourriaud’s case worse however is his apparent betrayal of the purpose of cultural theory in providing counter-hegemonic ideas and alternatives. The theorists of postmodernism overthrew the project of modernity in an attempt to save humanity from further nuclear extermination or genocide which had proved the ultimate conclusions of reason. Their cultural vision for postmodernism was also to provide an alternative or an antidote to the new ways of life dictated by post-industrial society. Not only does the vision for altermodernism fail to provide an alternative to the devastating path to future down which ‘alterglobalisation’ is dragging us, but it also remarkably promotes the idea that we turn our backs on and ignore this future altogether. One of the paradigms for artistic approaches Bourriaud suggests is that artists look back in time rather than forward claiming that “history is the last uncharted continent” and therefore should be the focus of artistic attention.

Jeh Wadia’s excuse is easy to fathom – he is in it for the money, but Bourriaud’s seems harder to discern. He is driven by a burgeoning ego no doubt, but alongside this there seems to be a wider problem. A nostalgia for the good times and a refusal to give up privileges and luxuries appear to be endemic in the art world’s attitude to facing up to the realities of climate change. At Frieze Art Fair last year, cultural theorist Judith Williamson delivered a keynote lecture on what she called ‘the Culture of Denial‘. She outlined a view of the world not dissimilar to the definition of ‘the Age of Stupid’ (and indeed altermodernism) that this essay has been discussing, in which a denial of the impending future or perhaps an impossibility to comprehend its severity, prevents us from acting.

What was most interesting about her introduction, however, was the discussion of her deliberate decision not to mention ‘climate change’ in the material promoting the talk, but instead to refer to it more ambiguously as an exploration of “the skewed relationship between what we know and what we do” (Williamson 2008). She identifies the persistent ‘stigma’ attached to directly addressing this issue, describing the common perception of it being “annoying, gauche or over the top to bang on about climate change”. So she was forced to revert to covert tactics in order to sneak this pressing discussion onto the Frieze agenda – in the hope of inciting the beginning of a widespread realisation that the art world is walking the path towards its own destruction.

There seems no doubt that Bourriaud’s altermodernism is the cultural side-kick of ‘the Age of Stupid’. To write a Manifesto of our times at such a crucial make-or-break point in the history of humanity and not to mention the possibility of an impending disaster or offer any suggestions as to what artists and society in general can do to combat it, is not just denial – it’s stupidity.

The truth is that all the ‘ends’ and ‘deaths’ that postmodernism faced on hypothetical grounds are now fast approaching our generation as a reality. Foucault’s famous conclusion to the seminal postmodern text ‘The Order of Things’, now seems all the more poignant:

“If those arrangements were to disappear as they appeared, if some event of which we can at the moment do no more than sense the possibility… were to cause them to crumble… then one can certainly wager that man would be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.” (Foucault 1994, p.422)

The main character in the The Age of Stupid is an archivist. In 2055, he sits alone in an expansive tower known as the ‘the World Archive’, which houses all the works of art, books, images, film etc ever produced by the human race. It is at this point that you realise this preservation is futile. Art is, after all, a human creation – it relies on humanity to provide its meaning. Without this crucial element it may as well cease to exist. Should it not, therefore, be art and culture that lead the way for the rest of society? To be the first to snap out of this ‘culture of denial’; to overcome the ‘stigma’; to do everything in its power to save humanity, and itself in the process.

Future Encyclopedia Entry: The Age of Stupid

The Age of Stupid constitutes the period between the ascent of the internal combustion engine in the late-19th century and the crossing of the 2c threshold to runaway global warming in the mid-21st.

This era was characterised by near-total dependence on energy from fossil hydrocarbons, together with exponentially increasing consumption based on the destruction of finite natural resources.

The institutionalised lack of foresight regarding future human welfare that held sway during this time earned the period its popular name, but scientists know this era as the Anthropocene: the period during which human activities came to be the dominant influence on the Earth’s biosphere and climate. The end of the Age of Stupid is marked by the sixth major mass extinction event, with the fifth being the K-T asteroid impact which ended the Age of the Dinosaurs. The abrupt loss of the majority of plant and animal species between 2020 and 2090 was followed by a crash in the human population, to just 7.4% of the 9 billion people alive at its peak.

Some historians argue that the Age of Stupid more properly refers to the narrower period between 1988 and 2015, during which humanity had become aware of the likely consequences of continuing to increase greenhouse gas emissions and still had time to avert catastrophe, but largely chose to ignore the warnings.

This article can also be found at:

Original text at Ellie Harrison’s web site – http://www.ellieharrison.com/index.php?pagecolor=7&pageId=press-summerreading

Edited version at The Nottingham Visual Arts web site – http://www.nottinghamvisualarts.net/writing/jun-09/altermodernism-age-stupid