Saturday 11th November

A Free All Day Event in Finsbury Park

Future Machine creates rituals for when the future comes. It will next appear in Finsbury Park on Saturday 11th November 2023.

When the Future Comes is a series of artist’s interventions each witnessed by a mysterious and mystical device – the Future Machine, led by Rachel Jacobs. A newly formed ritual or special occasion will emerge as the Future Machine appears in Oxfordshire, Nottingham, Cumbria, Somerset and London every year – until 2050 the year scientists predict will be a watershed for more extreme climate and environmental change.

From 10.00 am

Future Machine will meander around the park, meeting people along the way.

11.00 am

Join Future Machine and artists Esi Eshun & Rachel Jacobs for a guided walk to seven trees.

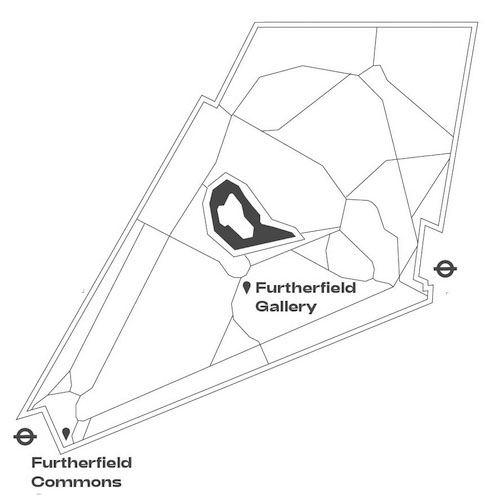

Gather outside Furtherfield Gallery (by the playground, close to the lake at the top of the hill).

From 2.00pm

Meet Future Machine and speak to the future at Furtherfield Commons (between the Seven Sisters Road & Finsbury Park Gates).

Celebrate the weather with musicians from around the world and take part in family activities including drumming and dancing.

Listen to live West African fusion music performed by the group, Zantogola!

Supported using public funding by Arts Council England, Furtherfield, Horizon (University of Nottingham) and in-kind support from Primary and the British Antarctic Survey

Join us for the workshop that is also a game where we use roleplay to explore how personal and collective data practices and devices might shape the attitudes and fortunes of a society?

Sign up by 12th August 2020

Participants will each receive one of two devices in the post, and will be given different roles to play as delegates in a fictional trade negotiation. In this first meeting on record, and with minimal knowledge of each other’s cultures, the people of Ourland and New Bluestead must use their devices to communicate with each other and to agree to the terms of a technology and data-culture exchange.

What do they have to offer? How will they decide what they want and what is in their best interests?

What freedoms might they sacrifice, what insights might they gain?

How might they adapt a foreign technology to their own needs, and how might they understand the risks involved?

This is an invitation to participate in Transcultural Data Pact, a research event that is also a game of serious make believe. We welcome you to a future-historic event and clash of data-cultures.

The event will take place online in Zoom and will last for about 3 hours with a lunchtime pre-event orientation session that will last for an hour.

There are two sessions available for both the game event and the pre-event orientation (which is a requirement of participation):

Lunchtime pre-game orientation events

13.30 – 14.30 BST Tues 18 August 2020

13.30 – 14.30 BST Wed 19 August 2020

Transcultural Data Pact Game events

13.15 – 16.30 BST Thurs 20 August 2020

13.15 – 16.30 BST Fri 21 August 2020

In exchange for your time you will exercise your creative agency contributing to the ideation of future technologies for live personal data. You might even discover new meanings in your personal data in places you never thought of looking before!

All participants will receive a £20 voucher for their contribution to the research.

This is an open invitation to all. No experience in role-playing games is necessary.

Pregame orientation events

13.30 – 14.30 to learn about your devices and about LARPing, to introduce and develop the scenarios, to build the fictional worlds together.

Game Event Schedule

13.20 – 13.30 Arrive in Zoom and sign in

13.30 Introduction

13.40 – 16.00 Nations Technology Exchange Live Action Role Play

16.00 – 16.30 Debrief, reflection and survey

For any enquiries, please email ruth.catlow@furtherfield.org

Findings contribute to a research paper Human-Computer Interaction (CHI).

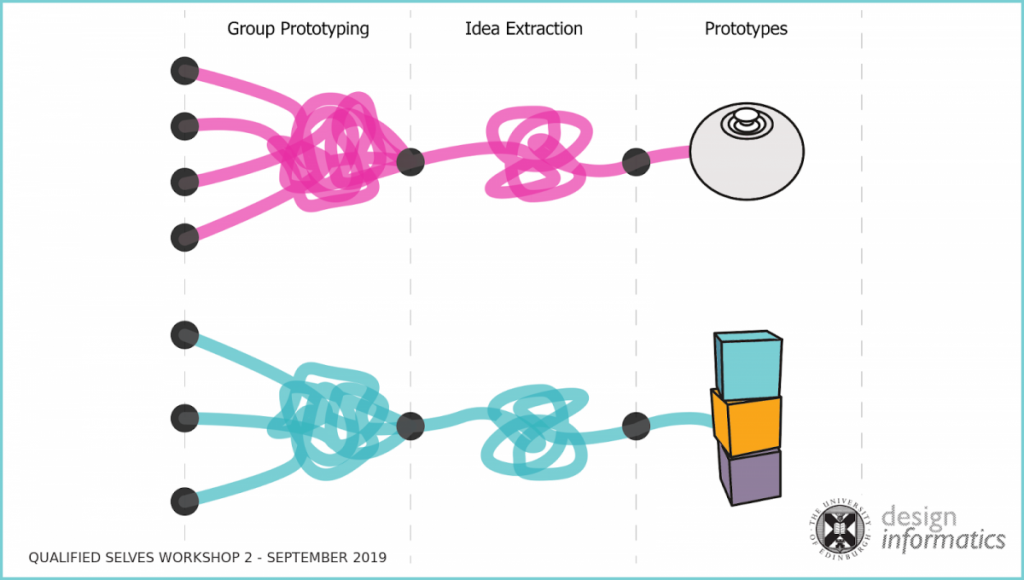

The Transcultural Data Pact is a Qualified Selves research event that uses data objects to stretch people’s imagination about the collection and usage of their own data to investigate personal and collective data devices and practices that add real value.

Qualified Selves is a joint project between Lancaster and Edinburgh Universities. Improving how individuals make sense of data management (from social media to activity trackers to home IoT devices) in order to enhance personal decision making, increase productivity, and improve their quality of life. Its novel approach to co-design and co-creation has supported the development of new prototypes to help think about tracking data in different ways. https://sensemake.org/

Transcultural Data Pact is created by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield/DECAL) with Dr Kruakae Pothong, Billy Dixon, Dr Evan Morgan and Prof. Chris Speed from Edinburgh University, in collaboration with Kate Genevieve.

Ruth Catlow is Director of DECAL. Furtherfield is London’s first (de)centre for digital arts. DECAL is a Furtherfield initiative which exists to mobilise research and development by leading artists, using blockchain and web 3.0 technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

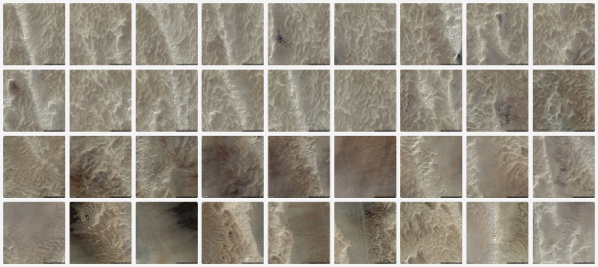

The new project by Guido Segni is so monumental in scope and so multitudinous in its implications that it can be a bit slippery to get a handle on it in a meaningful way. A quiet desert failure is one of those ideas that is deceptively simple on the surface but look closer and you quickly find yourself falling down a rabbit-hole of tangential thoughts, references, and connections. Segni summarises the project as an “ongoing algorithmic performance” in which a custom bot programmed by the artist “traverses the datascape of Google Maps in order to fill a Tumblr blog and its datacenters with a remapped representation of the whole Sahara Desert, one post at a time, every 30 minutes.”1

Opening the Tumblr page that forms the core component of A quiet desert failure it is hard not to get lost in the visual romanticism of it. The page is a patchwork of soft beiges, mauves, creams, and threads of pale terracotta that look like arteries or bronchia. At least this morning it was. Since the bot posts every 30 minutes around the clock, the page on other days is dominated by yellows, reds, myriad grey tones. Every now and then the eye is captured by tiny remnants of human intervention; something that looks like a road, or a small settlement; a lone, white building being bleached by the sun. The distance of the satellite, and thus our vicarious view, from the actual terrain (not to mention the climate, people, politics, and more) renders everything safely, sensuously fuzzy; in a word, beautiful. Perhaps dangerously so.

As is the nature of social media platforms that prescribe and mediate our experience of the content we access through them, actually following the A quiet desert failure Tumblr account and encountering each post individually through the template of the Tumblr dashboard provides a totally different layer to the work. On the one hand this mode allows the occasional stunningly perfect compositions to come to the fore – see image below – some of these individual ‘frames’ feel almost too perfect to have been lifted at random by an aesthetically indifferent bot. Of course with the sheer scope of visual information being scoured, packaged, and disseminated here there are bound to be some that hit the aesthetic jackpot. Viewed individually, some of these gorgeous images feel like the next generation of automated-process artworks – a link to the automatic drawing machines of, say, Jean Tinguely. Although one could also construct a lineage back to Duchamp’s readymades.

Segni encourages us to invest our aesthetic sensibility in the work. On his personal website, the artist has installed on his homepage a version of A quiet desert failure that features a series of animated digital scribbles overlaid over a screenshot of the desert images the bot trawls for. Then there is the page which combines floating, overlapping, translucent Google Maps captures with an eery, alternately bass-heavy then shrill, atmospheric soundtrack by Fabio Angeli and Lorenzo Del Grande. The attention to detail is noteworthy here; from the automatically transforming URL in the browser bar to the hat tip to themes around “big data” in the real time updating of the number of bytes of data that have been dispersed through the project, Segni pushes the limits of the digital medium, bending and subverting the standardised platforms at every turn.

But this is not art about an aesthetic. A quiet desert failure did begin after the term New Aesthetic came to prominence in 2012, and the visual components of the work do – at least superficially – fit into that genre, or ideology. Thankfully, however, this project goes much further than just reflecting on the aesthetic influence of “modern network culture”2 and rehashing the problematically anthropocentric humanism of questions about the way machines ‘see’. Segni’s monumental work takes us to the heart of some of the most critical issues facing our increasingly networked society and the cultural impact of digitalisation.

The Sahara Desert is the largest non-polar desert in the world covering nearly 5000 km across northern Africa from the Atlantic ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east, and ranging from the Mediterranean Sea in the north almost 2000 km south towards central Africa. The notoriously inhospitable climate conditions combine with political unrest, poverty, and post-colonial power struggles across the dozen or so countries across the Sahara Desert to make it surely one of the most difficult areas for foreigners to traverse. And yet, through the ‘wonders’ of network technologies, global internet corporations, server farms, and satellites, we can have a level of access to even the most problematic, war-torn, and infrastructure-poor parts of the planet that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago.

A quiet desert failure, through the sheer scope of the piece, which will take – at a rate of one image posted every 30 minutes – 50 years to complete, draws attention to the vast amounts of data that are being created and stored through networked technologies. From there, it’s only a short step to wondering about the amount of material, infrastructure, and machinery required to maintain – and, indeed, expand – such data hoarding. Earlier this month a collaboration between private companies, NASA, and the International Space Station was announced that plans to launch around 150 new satellites into space in order to provide daily updating global earth images from space3. The California-based company leading the project, Planet Labs, forecasts uses as varied as farmers tracking crops to international aid agencies planning emergency responses after natural disasters. While it is encouraging that Planet Labs publishes a code of ethics4 on their website laying out their concerns regarding privacy, space debris, and sustainability, there is precious little detail available and governments are, it seems, hopelessly out of date in terms of regulating, monitoring, or otherwise ensuring that private organisations with such enormous access to potentially sensitive information are acting in a manner that is in the public interest.

The choice of the Sahara Desert is significant. The artist, in fact, calls an understanding of the reasons behind this choice “key to interpret[ing] the work”. Desertification – the process by which an area becomes a desert – involves the rapid depletion of plant life and soil erosion, usually caused by a combination of drought and overexploitation of vegetation by humans.5 A quiet desert failure suggests “a kind of desertification taking place in a Tumblr archive and [across] the Internet.”6 For Segni, Tumblr, more even than Instagram or any of the other digitally fenced user generated content reichs colonising whatever is left of the ‘free internet’, is symbolic of the danger facing today’s Internet – “with it’s tons of posts, images, and video shared across its highways and doomed to oblivion. Remember Geocities?”7

From this point of view, the project takes on a rather melancholic aspect. A half-decade-long, stately and beautiful funeral march. An achingly slow last salute to a state of the internet that doesn’t yet know it is walking dead; that goes for the technology, the posts that will be lost, the interior lives of teenagers, artists, nerds, people who would claim that “my Tumblr is what the inside of my head looks like”8 – a whole social structure backed by a particular digital architecture, power structure, and socio-political agenda.

The performative aspect of A quiet desert failure lies in the expectation of its inherent breakdown and decay. Over the 50 year duration of the performance – not a randomly selected timeframe, but determined by Tumblr’s policy regulating how many posts a user can make in a day – it is likely that one or more of the technological building blocks upon which the project rests will be retired. In this way we see that the performance is multi-layered; not just the algorithm, but also the programming of the algorithm, and not just that but the programming of all the algorithms across all the various platforms and net-based services incorporated, and not just those but also all the users, and how they use the services available to them (or don’t), and how all of the above interact with new services yet to be created, and future users, and how they perform online, and basically all of the whole web of interconnections between human and non-human “actants” (as defined by Actor- network theory) that come together to make up the system of network, digital, and telecommunications technologies as we know them.

Perhaps the best piece I know that explains this performativity in technology is the two-minute video New Zealand-based artist Luke Munn made for my Net Work Compendium – a curated collection of works documenting the breadth of networked performance practices. The piece is a recording of code that displays the following text, one word at a time, each word visible for exactly one second: “This is a performance. One word per second. Perfectly timed, perfectly executed. All day, every day. One line after another. Command upon endless command. Each statement tirelessly completed. Zero one, zero one. Slave to the master. Such was the promise. But exhaustion is inevitable. This memory fills up. Fragmented and leaking. This processor slows down. Each cycle steals lifecycle. This word milliseconds late. That loop fractionally delayed. Things get lost, corrupted. Objects become jagged, frozen. The CPU is oblivious to all this. Locked away, hermetically sealed, completely focused. This performance is always perfect.”

Guido Segni’s A quiet desert failure is, contrary to its rather bombastic scale, a finely attuned and sensitively implemented work about technology and our relationship to it, obsolescence (planned and otherwise), and the fragility of culture (notice I do not write “digital” culture) during this phase of rapid digitalisation. The work has been released as part of The Wrong – New Digital Art Biennale, in an online pavilion curated by Filippo Lorenzin and Kamilia Kard, inexactitudeinscience.com.

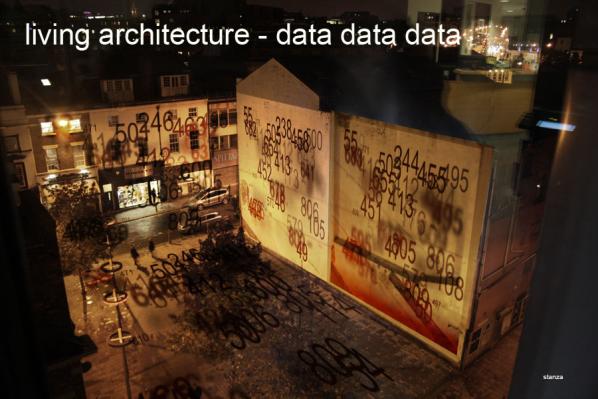

Stanza is an internationally recognised artist who has been exhibiting worldwide since 1984. He has won so many prizes you’d have trouble fitting them all on one mantlepiece. He has exhibited over fifty exhibitions globally and is an expert in arts technology, CCTV, online networks, touch screens, environmental sensors, and interaction. His artworks examine artistic and technical perspectives, within the contexts of architecture, data spaces and online environments.

Recurring themes throughout his career include the urban landscape, surveillance culture, privacy and alienation in the city. Stanza is interested in the patterns we leave behind, and real time networked events, that are usually re-imagined and sourced for information. He uses multiple new technologies so to create distances between real time, multi point perspectives that emphasis a new visual space. The purpose of this is to communicate feelings and emotions that we encounter daily which impact on our lives and which are outside our control.

Much of his work has centered on the idea of the city as a display system and various projects have been made using live data, the use of live data in architectural space, and how it can be made into meaningful representations. See Publicity, Robotica, Sensity, as well as a whole series of work manipulating real time CCTV data to making artworks with them: See, Velocity, Authenticity, Urban Generation. These works reform the data, work with the idea of bringing data from outside into the inside, and then present it back out again in open ended systems where the public is often engaged in or directly embedded in the artwork. Interactive and visually appealing, his style also maintains the substantive power through multi-facetted content.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Stanza: I don’t really get inspiration from the “who” question, I prefer the “what” and “why” questions. As a professional artist I look at loads of art so to understand what art is and can be, and it’s always an ever changing and fluid response. I also spend a lot of time ignoring stuff and material; (focused ignoring) because it has become harder and harder to see though the fog; the noise of it all. Maybe it’s better to think of a working model for inspiration, Andy Warhol had one. Just make the work. That’s what I do. I am not a part time artist in academia or an artist with another job, I’ve done this for the last thirty years, inspired by and in response to the world around me.

This dogmatic commitment to my work comes from my believes that the system you have to trust and invest in yourself. Inspiration, quite literally is everything all around you all at once, all at the same time, moment by moment. This is what inspires my work and it influences the creation of real time information flows, and works in parallel realities. It allows me to stand back at a distance and work with complex data sets while at the same time making meaning from them. Forming data into a shape, because this confluence might inspire a repositioning of thought and values while at the same time unlocking a hidden meaning to enable the viewer to feel and experience something new or to do something creative with the results.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

S: There’s a saying be careful what you wish for. If one reverses this then it could be wish for what you want and need. Influence is problematic because it’s both negative and positive. The idea of influence seems causal, but my own practise isn’t based on influence but in research into certain themes. This enables me to get into both sides of particular questions or debate, so to frame the work I make. Works like these have been inspired by this focus…

The Singing Trees, focus in the invisible things and the environment http://stanza.co.uk/tree/index.html

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

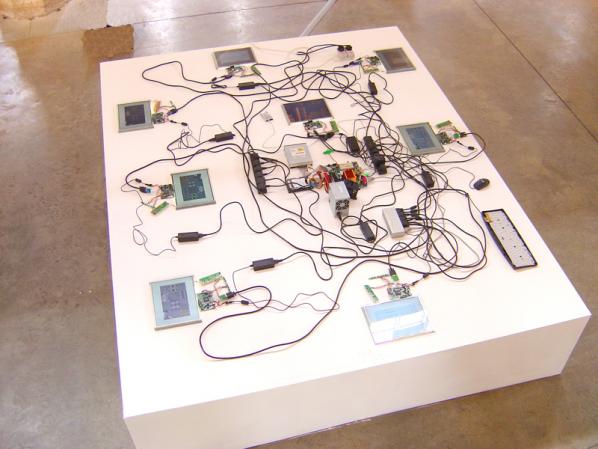

S: I have been researching smart cites, urbanisn, and have collected ‘big data’ since 2004. I have been building my own wireless sensor network. This eventually manifested itself in an artwork called Capacities in 2010 which then influenced all the others in the series until it now has this form.

Capacities: Life In The Emergent City, captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork

http://stanza.co.uk/capacities/index.html

Which led to…

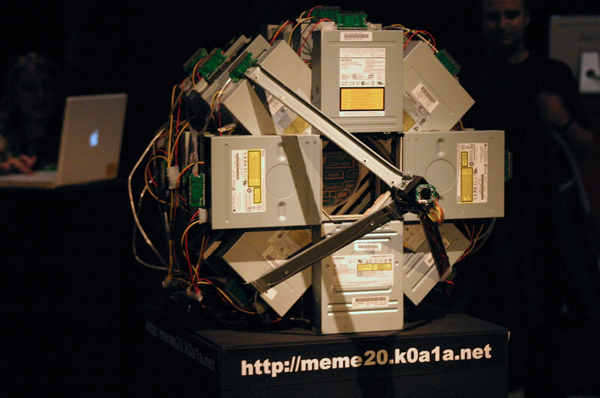

The Nemesis Machine- From Metropolis to Megalopolis to Ecumenopolis.

“A Mini, Mechanical Metropolis Runs On Real-Time Urban Data. The artwork captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork. The artwork explores new ways of thinking about life, emergence and interaction within public space. The project uses environmental monitoring technologies and security based technologies, to question audiences’ experiences of real time events and create visualizations of life as it unfolds. The installation goes beyond simple single user interaction to monitor and survey in real time the whole city and entirely represent the complexities of the real time city as a shifting morphing complex system.

The data and their interactions – that is, the events occurring in the environment that surrounds and envelops the installation – are translated into the force that brings the electronic city to life by causing movement and change – that is, new events and actions – to occur. In this way the city performs itself in real time through its physical avatar or electronic double: The city performs itself through an-other city. Cause and effect become apparent in a discreet, intuitive manner, when certain events that occur in the real city cause certain other events to occur in its completely different, but seamlessly incorporated, double. The avatar city is not only controlled by the real city in terms of its function and operation, but also utterly dependent upon it for its existence.”

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

S: It’s the museum I would like to change or engage with. It seems that anything and everything will end up in the museum. We have become the museum. We are the sum of our collections catalogs and archives. Since the current trend is for public engagement we will see a mix of these new technologies aiding and abetting this and various dialogues.

Therefore these questions need to be raised more vocally. How do visitors interact with each other and artworks? How do visitors behave in public space and what patterns or communities do they form. Can these outputs reshape our experience of public space and the art?

So, new immersive technologies could be used to investigate how visitors interact with art works, with each other and what impact their experiences have in forming new user interactions within public space. This space could be made more social and lead to new real time artworks based on visitor interaction and new visualizations of the gallery space based on gathered data.

Artists used to occupy specific issues but now there aren’t many topics artists haven’t engaged in or reached out to. The issues that will resonate will be the ones closest to the issue of the day…. and, they will be economics, the environment and migration. Because of this I would like to less focus on public engagement spectacle or entertainment and more on the quality and public engagement rooted in intellectual rigour.

Technology affords new ways of working with audiences and curators as participants in artworks. The concept of the exhibition as an active site for experimentation and collaboration between curators, artists and audiences prefigures a general cultural movement towards the centrality of experience and away from the reification of the object.

However, how audience activities and movements can be used as the subject of new artwork as well as modify engagement with existing collections is a cultural and technological challenge.

SeePublic Domain: You Are My Property, My Data, My Art, My Love.

The Public Domain Series involves using live CCTV systems that are already installed then using these cameras to enhance gallery space and the audiences experience of the gallery. http://stanza.co.uk/public_domain_outside/index.html

Visitors to a Gallery – referential self, embedded. Stanza uses a live CCTV system inside an art gallery to create a responsive mediated architecture. Anyone in any of the galleries and all spaces in the building can appear inside the artwork at any time.

http://stanza.co.uk/cctv_web/index.html

The social challenge within urban space is one I like to play with. In The Binary Graffiti Club, is a project I set up to try and work in this area. The Binary Graffiti Club are invited members of the public at each location for each event; they are given the hoodie to keep as thanks for their participation and contribution. The Binary Graffiti Club set off across the city and create artworks.

http://stanza.co.uk/binary_club/index.html

“Youths dressed in black hoodies swarmed the historic city streets of Lincoln during Frequency Festival 2013, their backs emblazoned with bold white digits, the zeros and ones. Their ominous presence was marked with a series of binary code graff-tags on official buildings throughout the city; messages of insurrection for a digital cult now active among us or analogue reminders of the digital soup of signals we wade through on a daily basis? There’s an engaging playfulness and an aesthetic pleasure to Stanza’s work that pays rewards on deeper investigation. His urban interventions remind us of the invisible occupation of the cyberspace around us and encourages us to ask whose hand manipulates these systems of control.” Barry Hale, Festival Co-Director of Frequency Festival 2013: Stanza: Timescapes/Binary Graffiti Club.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

The invention of the toothpaste tube caused a revolution in painting.

The greatest discovery of the age was that the world is full of atoms.

Doing many small things instead one on big thing.

We seam to victimise out children we give them ASBO’S and anti social behaviour orders. For a while I wanted one. They actually give you a certificate like rockers, mods punks etc. The hoodie is a symbol of youth culture as well as being anti social. My new artwork the Reader and the idea of reading books and being anti-social led to this project.

The Reader is a large six foot sculpture of the artist Stanza wearing a hoodie reading a book. The artwork is a metaphor for the engagement of reading in the digital age. The sculpture acts as a focal point for community and public engagement and has taken over one year to make and design; it has been commissioned to act as a focal point for the identity of the library. The reader reads all the books published since 1953 inside a data body sculpture. http://stanza.co.uk/TheReader_web/

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and or social change?

S: Make work, make more work, and remember nothing lasts forever except true love.

Re: Art, Study it

Re: Technology. Learn it

Re: Social change . Be part of it.

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

Yes the Books…

The Bible The Quran And The Torah.

Because…they are the most influential books ever written and have guided the lives of billions so it’s a good idea to have had a read… at least “view” them.

See…

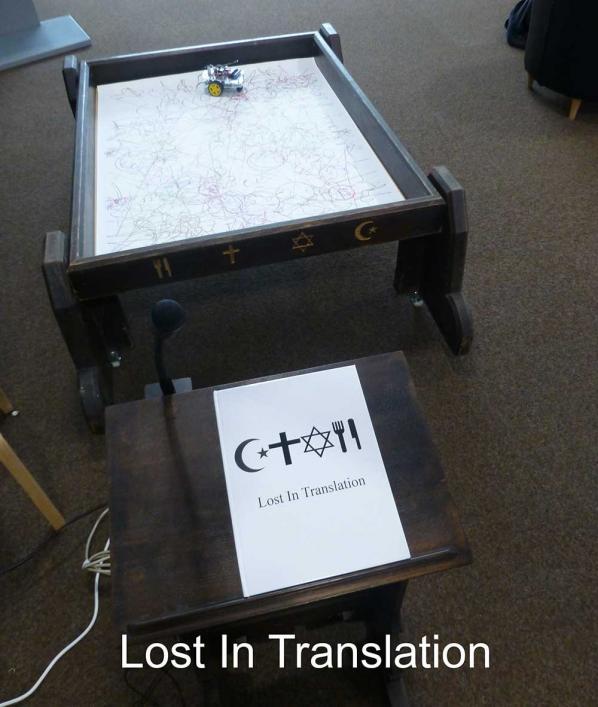

Lost in Translation. This custom made robot responds to a series of texts and makes drawings unique to each reader. The work questions not only the meaning and interpretation of text but just who controls our understanding of the outputs and indeed what is Lost In Translation. This is a very playful user friendly work and actively engages the audience not only to think about the text but the meaning of how automation and networked technology is changing the control of understanding. http://stanza.co.uk/lost_in_translation/

Thank you…

Dave Young writes within the context of Localhost: RWX, a symposium and worksession at Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop from 29-31 October 2015. For more information about RWX, visit the Localhost website. RWX is funded by Creative Scotland, with support from New Media Scotland, Furtherfield, and Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

As smart devices shape the near future of personal computing, we – as users – are experiencing a shift in the way digital data is represented and accessed. For the last five years, Apple, Google and the other tech giants have desperately attempted to position themselves as market innovators and patent holders in the next generation of consumer tech. Over this period, we have seen more companies dropping desktop PC production in favour of novel gadgets such as smart phones, tablets, watches, fitness bands – and even contact lenses, glasses, and so on. A noticeable side-effect of this shift is that the ‘traditional’ filesystem interface, familiar to us as a visually traversable hierarchical structure of files and folders, is replaced by an app-centric interface. With its primary objective of being more user-friendly, this kind of interface limits as much as possible the tedious and touchscreen-hostile tasks of file management and directory navigation. It’s certainly worth reviewing how data should be represented in the modern Operating System – “tradition” is not enough reason to purposefully stick to an old system of files/folders, created by Xerox for their Alto/Star OS in the 1970s. That said, any radical change in the interface design of the filesystem needs to be critiqued, as it is acts as the mediator between us, our data, and our tools.

It’s worth emphasising that the aforementioned Xerox system is also a metaphor – it does not necessarily offer us a truer insight into the raw data on our devices than an app would. In the case of wanting to open a .txt file, whether we do this by selecting files via OSX’s Finder/Windows Explorer/one of the myriad File Managers in the world of Linux, or by opening an app on a “smart OS” such as iOS/Windows Phone/Android, we still achieve the same end goal: while the rudiments of the interface might change from one system to another, the .txt file is still utimately accessed and displayed to the screen. But between the traditional Xerox system and newer mobile interfaces, there is an interesting divergence. In the former instance, we navigate to the information, the precise location of the particular file /within/the/hierarchy/of/directories, then choose to open it with a tool of our selection. In the latter case, we select the tool, which then prescribes what information can be accessed with it. This simple inversion of intent does fundamentally alter our experience of the filesystem, but what’s at stake when we prioritise the choice of tool over the choice of file?

In the case of the former interface, we are provided with a visual map of our data. We can see where something is stored, how it relates to the other data we have saved, and also its related metadata. We are presented with an open scope, an indexical view of the files stored in our device’s memory. By default, we have the option of surveying data saved to our hard drive, and we can choose to ‘explore’ this should we so desire.

In the case of the typical smart OS interface, where the selection of a tool is prioritised over the selection of a given file, our vision of the filesystem is closed down by a “helpful” framework that only displays data that can be opened with a particular app. The messages app allows you to read your messages, the note-taking app allows you to speedily write notes, yet ne’er the twain shall meet – unless through a closed black-box framework, often labelled as ‘share’, which again guides you to an app that mediates your selection of file. As if peering through a keyhole, the user sees their filesystem in discreet parts and at particular moments, mediated by a given app’s functionality and filetype preferences.

It must also be said that, increasingly, much in-app data is often not even locally hosted on the device. It occupys no discernible, indexed space on its hard disk – at least no space that is visible and open to the user. Instead, it sits in a dynamic, transient “app cache”, where information is stored temporarily, to be frequently written, updated, and wiped without the user’s explicit knowledge or conscious intervention.

But this problem has a simple solution: why not just download a file manager from an app store?! It is of course an easy task to download a third-party file manager, but why was the filesystem manager done away with in the first place? Default configurations are rarely inert gestures. The omission of a stock file manager should be understood as a deliberate design decision intended to influence or shape the way we engage with the device. Is its omission, for instance, a desire to shake up what is seen as an antiquated interface? Is it a victim of contemporary design obsession about UI friction and clutter?

Searching for a file in a directory tree and not being able to find it can be seen as an example of friction. It is a moment where the ‘user’ becomes aware that they are ‘using’, activated by frustration or self-reflexive concentration and the necessity to make decisions, to search, to solve a problem. Finding the lost file is a terribly banale puzzle, but one that at least self-conciously engages the user. The app interface, which always tries to guess what you want to do next under its chief design objective of smooth simplicity, aims to remove friction. The smart OS is not free from friction though: when it guesses wrong, a manual solution can be more complex to rectify than the traditional filesystem interface, and perhaps at this point, the user realises they may not be as free to ‘use’ their technology as they expect.

Recently, we can see how some features of the smart OS are invading the desktop Windows, Mac and (to a lesser extent) Linux Operating Systems. Ubuntu, the most popular desktop Linux OS, raised controversy when its new Unity interface was unveiled in 2012, with a noticeably touch-friendly design aesthetic featuring large app tiles and fancy but pointless UI features. Was this part of the wider trend as demonstrated by Apple and Windows, where an ecosystem of multiple devices share smart and responsive interfaces, homogenous no matter the screen size, format, or method of interaction? Since then, Canonical (the parent company that develops Ubuntu) have attempted to venture into the smartphone market, working on both software and hardware, with an OS that neatly ties into the Ubuntu desktop experience. This approach to smart OS design is not simply a matter of convenience for the user, but good business sense too, especially as it becomes increasingly common for a technically adept individual to have a computer at home, a tablet in their bag, a phone in their pocket and a smartwatch on their wrist. Interface and brand go hand in hand: a suite of devices that play nicely together, share files conveniently over fancy wireless protocols, and look good when sitting side-by-side on a coffee table further encourages brand loyalty.

Despite its somewhat unforgiving text-based interface, it is the Terminal that perhaps offers the least mediation of all filesystem interfaces. Commands are taken as commands, presumed to be intentional and subsequently applied, whatever the consequences. When developed according to the UNIX philosophy of “do one thing and do it well”, command-line tools have the ability to “pipe” a standard output to an input of another tool – that is, each tool can share its output with the input of the next tool. Tools and files are thus recombinant, and in their purest form, are not hidden from one another. A basic example, featuring an ASCII cow:

ls -a #lists all files in the current directory.

. .. My_Computer.gif .shhh_super-secret.file

ls -a | cowsay #the standard output of 'ls -a' is piped into the standard input of cowsay. Hence, an ASCII cow lists out files for us.

_____

< . .. My_Computer.gif .shhh_super-secret.file>

-----

\ ^__^

\ (oo)\_______

(__)\ )\/\

||----w |

|| ||

Or for example, the ‘cat’ command dumps the contents of any file into the terminal. It does not really matter what you try to ‘cat’ – it could be an image, or whatever is in the RAM of your computer – if you have Read permission it will duly carry out your command.

cat My_Computer.gif #prints file contents to standard output

GIF87a+#)#� ######�##�#�##�����#�#���#�����������������������,####+#)###�0�I��8�ͻ�`(��X�h���T#p,�GR#m#�8��@#��[#�7b�#h:�Ndϴ##���U�d##P+��~u#�v9,{ ��`.#��o#Zbg'�bM{ }#mxjp#��"?�ak�xG+~S�K#��;KAA<'&��#'L"a����#����#���#?��0(���������##4�MŹ#�##��3�#����#�I�8�68��#z�����<���7���)��-l��ڼ�#� ����C##*�###;

sudo cat /dev/mem #prints the contents of a device's Random Access Memory to standard output

Yet, despite its direct and explicit interpretation of user input , we must return to the fact that the command line is a simulation – or more appropriately, an emulation – of a interface that mediates our relationship with the digital information stored on disk. Its commands recursively refer to lower-level frameworks and architectures, until it reaches the level of bits and electrical pulses.

Ultimately, when we discuss these issues about interface and access to information , we come to much greater issues surrounding the essence of memory and access to knowledge itself. As with any indexical system of information management (whether we speak of the archive, the library, the museum, or indeed the filesystem), there are inherent biases in the structures of representation that mediate and inform how we relate to the information contained within. There is a strong history of theorists (Jacques Derrida’s writing in Archive Fever being the obvious one) who attack the politics of the archive and our habits of designing biased frameworks for the storage of memory – certainly useful in these times, when we shift from one interface whose biases are familiar to another whose biases still somewhat elusive and in flux .

In the present though, it has become increasingly clear that the interface bias of the smart OS prioritises data-access and content-delivery, focusing on consumption rather than production. Maybe a filesystem manager is surplus to requirement for many, yet the ommission of such a perspective on our filesystem creates some issues for us as users. The phenomenon of ‘black-boxing’ – whereby complex activity is cloaked and opaque, incomprehensible and impenetrable to the user – becomes normalised. As a consequence, we can’t easily understand the behaviour of an app and the data it produces/accesses, we can’t explore what logs exist on our devices, and what personal data is potentially exposed to typical threats such as viruses, malware, hacks, and thieves. The perspective we have is simplified, and in this case, to simplify is to remove options, alternatives, and user-agency. The use-possibilities of our devices are parametrised, governed, and constrained by the overarching system of app-centricity, while opportunities for subversive intervention and creative misuse are reduced as we are obliged to act and respond within the increasingly powerful context of app store regimes.

Those orphaned config files, scripts, metadata, caches, loggers and logs: they will continue to reside in our most obscure, exotic directories, unseen, but saved.

—-

Also Read

* Turing Complete User – Olia Lialina

* Preface to FLOSS+Art – Aymeric Mansoux and Marloes de Valk

* McKenzie Wark – A Hacker Manifesto

* The Interface Effect – Alexander Galloway

DOWNLOAD

PRESS RELEASE (pdf)

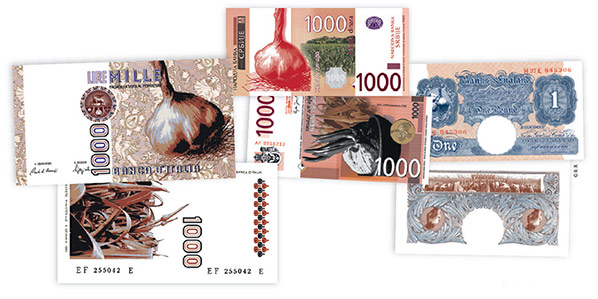

‘Agliomania, eating and trading my stinky roses’ by Shu Lea Cheang. Courtesy of the artist and MDC #76 We Grow Money, We Eat Money, We Shit Money.

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

Featuring Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion, Shu Lea Cheang, Sarah T Gold, Jennifer Lyn Morone, Rhea Myers, The Museum of Contemporary Commodities (MoCC), the London School of Financial Arts and the Robin Hood Cooperative.

Furtherfield launches its Art Data Money programme with The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies, an exhibition featuring artworks that reveal how we might produce, exchange and value things differently in the age of the blockchain.

Appealing to our curiosity, emotion and irrationality, international artists seize emerging technologies, mass behaviours and p2p concepts to create artworks that reveal ideas for a radically transformed artistic, economic and social future.

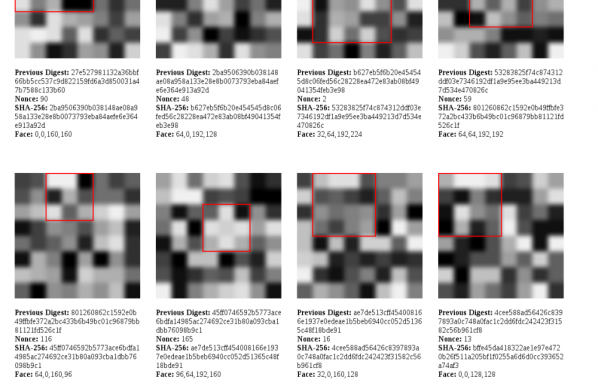

Have you ever looked for faces in the clouds, or in the patterns in the wallpaper? Well, Facecoin is an artwork that is a machine for creating patterns and then finding ‘faces’ in them. It is both an artwork AND a prototype for an altcoin (a Bitcoin alternative).

Facecoin creates patterns by taking the random sets of data used to validate Bitcoin transactions and converting them into grids of 64 grayscale pixels. It then scans each pixel grid, picking out the ones that it recognises by matching its machine-definition of a human face. Facecoin uses the production of “portraits” (albeit by a machine) as a proof-of-aesthetic work. Facecoin is a meditation on how we discern and value art in the age of cryptocurrencies.

Shareable Readymades are iconic 3D printable artworks for an era of digital copying and sharing.

Duchamp put a urinal in a gallery and called it art, thereby transforming an everyday object and its associated value. Rhea Myers takes three iconic 20th century ‘readymades’ and transforms their value once again. By creating a downloadable, freely licensed 3D model to print and remix, everyone can now have their own Pipe, Balloon Dog and Urinal available on demand. Click here to collect your own special edition version of these iconic artworks.

A hoard of golden trinkets to appeal to our inner Midas. An image projection of found GIFs, collected from the internet, creates a gloriously elaborate, decorative browser-based display hosted at www.goldandglitter.net. It prompts reflections on the value of gold in an age where the value of global currencies are underpinned primarily by debt, and where digital currencies are mined through the labour of algorithms.

Also by Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion:

Nakamoto (The Proof) – a video documenting the artists’ attempt to produce a fake passport of the mysterious creator of Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto.

Untitled SAS – a registered company with 10,000 shares that is also a work of art. SAS is the French equivalent of Corp or LTD. http://www.untitledsas.com/en

Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc reclaims ownership of personal data by turning her entire being into a corporation.

The Museum of Contemporary Commodities by Paula Crutchlow and Dr Ian Cook treats everyday purchases as if they were our future heritage. The project is being developed with local groups in Finsbury Park in partnership with Furtherfield.

The Alternet by Sarah T Gold conceives of a way for us to determine with whom, and on what terms, we share our data.

Shu Lea Cheang anticipates a future world where garlic is the new social currency.

Also, as part of Art Data Money, join us for data and finance labs at Furtherfield Commons.

LAB #1

Share your Values with the Museum of Contemporary Commodities

Saturday 17 October, 10:30am-4:30pm

A popular, data walkshop and lego animation event around data, trade, place and values in daily life.

Free – Limited places, booking essential

LAB #2

Breaking the Taboo on Money and Financial Markets with Dan Hassan (Robin Hood Coop)

Saturday 14 & Sunday 15 November, 11:00-5:00pmA weekend of talks, exercises and hands-on activities focusing on the political/social relevance of Bitcoin, blockchains, and finance. All participants will be given some Bitcoin.

£10 per day or £15 for the weekend – Limited places, booking essential

LAB #3

Building the Activist Bloomberg to Demystify High Finance with Brett Scott and The London School of Financial Arts

Saturday 21 & Sunday 22 November, 11:00-5:00pm

A weekend of talks, exercises and hands on activities to familiarise yourself with finance and to build an ‘activist Bloomberg terminal’.

£10 per day or £15 for the weekend – Limited places, booking essential

LAB #4

Ground Truth with Dani Admiss and Cecilia Wee

Saturday 28 November, 11-5pm

Exploring contemporary ideas of digital agency and authorship in post-digital society.

LAB #5

DAOWO – DAO it With Others

November/February

DAOWO – DAO it With Otherscombines the innovations of Distributed Autonomous Organisations (DAO) with Furtherfield’s DIWO campaign for emancipatory networked art practices to build a commons for arts in the network age.

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion (FR) are primarily concerned with issues related to new media, the new forms that they allow and the consequences they entail on our perception and behaviour.Their work has in particular received support from the François Schneider Foundation, FRAC – Collection Aquitaine, CNC/DICRéAM and SCAM. They have been exhibited in France and Europe, in places such as the Centquatre in Paris, the Vasarely Foundation in Aix-en-Provence, the Solo Project Art Fair in Basel or the Centre pour l’Image Contemporaine in Geneva, and are represented by the 22,48 m² gallery in Paris.

Shu Lea Cheang (TW/FR) is a multimedia artist who constructs networked installations, social interfaces and film scenarios for public participation. BRANDON, a project exploring issues of gender fusion and techno-body, was an early web-based artwork commissioned by the Guggenheim Museum (NY) in 1998.

Dr Ian Cook (UK) is a cultural geographer of trade, researching the ways in which artists, filmmakers, activists and others try to encourage consumers to appreciate the work undertaken (and hardships often experienced) by the people who make the things we buy.

Paula Crutchlow (UK) is an artist who uses a mix of score, script, improvisation and structured participation to focus on boundaries between the public and private, issues surrounding the construction of ‘community’, and the politics of place.

Sarah T Gold (UK) is a designer working with emerging technologies, digital infrastructures and civic frameworks. Alternet is Sarah T Gold’s proposal for a civic network which extends from a desire to imagine, build and test future web infrastructure and digital tools for a more democratic society.

Dan Hassan (UK) is a computer engineer active in autonomous co-operatives over the last decade; in areas of economics (Robin Hood), housing (Radical Routes), migration (No Borders) and labour (Footprint Workers). He tweets as @dan_mi_sun

Jennifer Lyn Morone (US) founded Jennifer Lyn Morone™Inc in 2014. Since then, her mission is to establish the value of an individual in a data-driven economy and Late Capitalist society, while investigating and exposing issues of privacy, transparency, intellectual property, corporate governance, and the enabling political and legal systems.

Rhea Myers (UK) is an artist, writer and hacker based in Vancouver, Canada. His art comes from remix, hacking, and mass culture traditions, and has involved increasing amounts of computer code over time.

Brett Scott (UK) is campaigner, former broker, and the author of The Heretic’s Guide to Global Finance: Hacking the Future of Money (Pluto Press). He blogs at suitpossum.blogspot.com and tweets as @suitpossum

The Human Face of Cryptoeconomies is part of Art Data Money, Furtherfield’s new programme of art shows, labs and debates that invites people to discover new ways for cryptocurrencies and big data to benefit us all. It responds to the increasing polarisation of wealth and opportunity, aiming to build a set of actions to build resilience and sustain Furtherfield’s communities, platforms and economies.

About Furtherfield

Furtherfield was founded in 1997 by artists Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow. Since then Furtherfield has created online and physical spaces and places for people to come together to address critical questions of art and technology on their own terms.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

Explore and discuss the data surveillance processes at play in Finsbury Park through a process of rapid group ethnography. Arrive from 5.30pm at Furtherfield Commons, the community lab space in Finsbury Park, for a short introduction to the project. We will leave at 6pm for a 90 minute walk around the area followed by food and discussion.

Please bring:

This walkshop event is part of the research and development for the Museum of Contemporary Commodities.

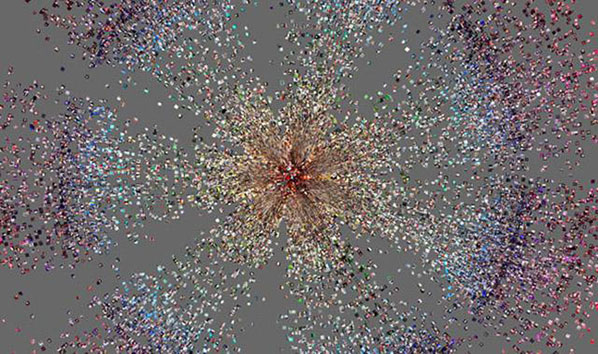

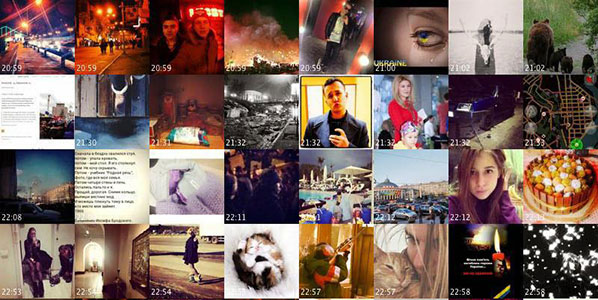

Featured image: 144 Hours in Kiev: Instagram montage, all images courtesy of Lev Manovich

Lev Manovich’s upcoming keynote, along with the entire Art of the Networked Practice online symposium, March 31 – April 2, 2015, will be free, open and accessible via web-conference from anywhere in the world. Visit the Website to register. The symposium is in collaboration with Furtherfield.

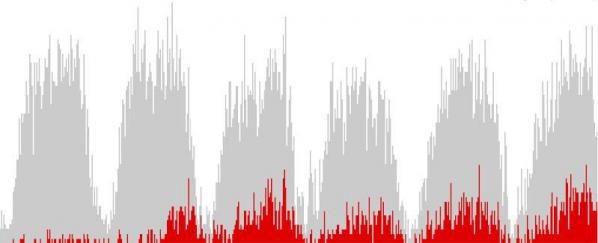

While big data has infiltrated our everyday lives, Lev Manovich and his collaborators have explored the data of everyday life as a window on social transformation. We discuss his latest work: The Exceptional and the Everyday: 144 Hours in Kiev, a portrait of political upheaval in the Ukraine constructed from thousands of Instagram photos taken over a six day period during the revolution in February of 2014. The project evolves from Manovich’s recent manifestations, Phototrails (2013) and SelfieCity (2014), metamorphosing social media into data landscapes.

Randall Packer: How do you view social media as illuminating a broader understanding of crisis in times of political upheaval?

Lev Manovich: When the media covers exceptional events such as social upheavals, revolutions, and protests, typically they just show you a few professionally shot photographs that focus on this moment of protest at particular points in the city. So we were wondering if examining Instagram photos that were shared in the central part of Kiev would give us a different picture. Not necessarily an objective picture because Instagram has its own biases and it’s definitely not a transparent window into reality, but would give us, let’s say, a more democratic picture. So we’ve downloaded over 20,000 photos shared by 6,000 people, and using visualization we created a number of different views of reality with patterns contained in the data. And we were particularly interested to see how the images of the everyday exist side by side with images of extraordinary events: how images of demonstrations, confrontation with government forces, fire, smoke, and barricades exist next to selfies, parties, or empty streets.

RP: Is it possible to think of what you are doing as taking an activist position in terms of revealing truths about a political situation?

LM: We have to be careful because obviously what you are seeing in 144 Hours in Kiev is a relatively small part of the population. Because the people who do use Instagram create tags mostly in English, they are, maybe, pro-Western people. But it allows us to get a sense of, not necessarily of a truth, not necessarily of what’s real, but let’s say a different kind of picture, a different place of reality then what the journalists would get. Because journalists may go, talk to a few people, and then come up with a report. But here you have “quotes,” so to speak, of thousands of people.

RP: Do you also see the collections of visualizations from user-generated images as an aesthetic realization?

LM: Perhaps one thing we can highlight is the idea of expressive visualization. As an artist I am also interested in the question of how can I present the world through the data. So let’s say a hundred years ago I would be taking photographs of a city. Now I can represent the city through 2 million Instagram photos. Thinking about landscape paintings in Impressionism, Fauvism, or even Cubism, how could I represent nature today through the contributions of millions of people? So I think of myself as an artist who is painting with data.

RP: But I’ve noticed that there is a focus in your writing on scientific methodology, you don’t talk very much about the renderings from an artistic perspective.

LM: It’s very clear that we’re taking ideas and techniques that have been used by modern artists. The difference is that we are pulling out data and writing open source tools. We’re taking in this case social media, works that were not created by us, and then putting them through different kinds of combinations. If you think about modernist collage of the city from the 1910s or 1920s, using pieces of newspaper and other existing media, what we’re doing exists in the same tradition.

RP: In many ways, the works can be fully appreciated as collage or composites, which I imagine goes against what you are trying to say through data analysis.

LM: No, it doesn’t go against what we are doing. It’s a matter of speaking to different parts of society. So you don’t just talk to designers or artists or like-minded people, you also talk to scientists. But ultimately what drives me is that I can I create something expressive, something unique, that isn’t just simply a data visualization, but creates an image that finds visual forms, that finds the right metaphors, which allows me to talk about modern society as consistent with its millions of data points. To me I think it’s a successful metaphor for how to speak about society today, when you think about all the traces you leave on social networks. I am trying to find the static visual forms to represent our new sense of society from seemingly random acts of individual people.

RP: Talk about the idea of “collective stories,” which are revealed in the composite of hundreds of thousands Instagram photos, each of which is a story in and of itself.

LM: We bring all these narratives together and try to make a kind of composite “film.” The connection to documentary, such as filmmakers like Dziga Vertov, for me is very clear. When Dziga Vertov, for example, was making his films in Kiev, he would have several cameramen in different parts of the Soviet Union shooting everyday, and they would send it to him and he would put it all together. So my “films” are made up of downloaded visuals, in which you can then make multiple “films” out of.

RP: Is it possible that the individual stories, the individual voice of expression, might get lost in this broad swath of data mining and cultural analytics?

LM: People are documenting what they think is interesting and important in their lives. But because there are very particular behaviors, what you get is a kind of pattern. I would say that patterns are not the same thing as a story. I don’t think of it as traditional narrative art, but rather a pattern of certain repeating behaviors.

RP: How do you position the work you are doing in the context of the current crisis of invasive surveillance and the loss of privacy resulting from big data analysis?

LM: When we started thinking about these ideas in 2005, these issues were not on the table. In the last two or three years they have become central and to be honest they keep me up at night. I consider whether or not it’s OK because there are histories of governments using photographs of protests of honest people. I think the first time it happened seriously was in Prague in 1968 when it was raided by the Soviet Union. You had bystanders taking pictures, and when the pictures were found they were used to arrest people. So we thought a lot about it. When you start to individualize stories, when you start following particular people, then it gets really dangerous.

RP: In this sense its a very political project. What you have done is revealed that in the 21st century of social media it’s difficult to hide anything. What have you learned about contemporary life as seen through the lens of social media?

LM: This is a deep question. I’m basically trying to say that as opposed to a journalist who thinks about the “data” as a kind of truth, that it’s a way to find out what happened, what I’m thinking about is its own reality. It’s not a question of truth, it’s a question of making interesting connections.

RP: That’s the difference between an artist and a journalist or even a scientist. You’re absorbing and you’re finding the connections but you’re not trying to say: this is it.

LM: I think the main answer is this: we can produce different visualizations out of the same data. Everyone views a different idea. It’s like when Monet paints another cathedral, there is not one painting that is correct. He makes a dozen paintings where every painting represents a different color, different atmospheric conditions, to show that in fact there are only the subjective views. So the goal is perhaps not to give people a new interpretation, but rather to challenge what they may be thinking is the correct one.

The Everyday and the Exceptional: 144 Hours in Kiev is a project of Lev Manovich in collaboration with Dr. Mehrdad Yazdani, Alise Tifentale, and Jay Chow.

Featured image: Your Fingerprints on the Artwork Are The Artwork Itself

In a work commissioned by curator Shiri Shalmy for the Open Data Institute‘s ongoing project Data as Culture, artist Paolo Cirio confronts the prerequisites of art in the era of the user. Your Fingerprints on the Artwork are the Artwork Itself [YFOTAATAI] hijacks loopholes, glitches and security flaws in the infrastructure of the world wide web in order to render every passive website user as pure material. In an essay published on a backdrop of recombined RAW tracking data, Cirio states:

Data is the raw material of a new industrial, cultural and artistic revolution. It is a powerful substance, yet when displayed as a raw stream of digital material, represented and organised for computational interpretation only, it is mostly inaccessible and incomprehensible.

In fact, there isn’t any meaning or value in data per se. It is human activity that gives sense to it. It can be useful, aesthetic or informative, yet it will always be subject to our perception, interpretation and use. It is the duty of the contemporary artist to explore what it really looks like and how it can be altered beyond the common conception.

Even the nondescript use patterns of the dataasculture.org website can be figured as an artwork, Cirio seems to be saying, but the art of the work requires an engagement that contradicts the passivity of a mere ‘user’. YFOTAATAI is a perfect accompaniment to Shiri Shalmy’s curatorial project, generating questions around security, value and production before any link has been clicked or artwork entertained. Feeling particularly receptive I click on James Bridle’s artwork/website A Quiet Disposition and ponder on the first hyperlink that surfaces: the link reads “Keanu Reeves“:

“Keanu Reeves” is the name of a person known to the system.

Keanu Reeves has been encountered once by the system and is closely associated with Toronto, Enter The Dragon, The Matrix, Surfer and Spacey Dentist.

In 1999 viewers were offered a visual metaphor of ‘The Matrix’: a stream of flickering green signifiers ebbing, like some half-living fungus of binary digits, beneath our apparently solid, Technicolor world. James Bridle‘s expansive work A Quiet Disposition [AQD] could be considered as an antidote to this millennial cliché, founded on the principle that we are in fact ruled by a third, much more slippery, realm of information superior to both the Technicolor and the digital fungus. Our socio-political, geo-economic, rubber bullet, blood and guts world, as Bridle envisages it, relies on data about data. The title of AQD refers to The Disposition Matrix, a database developed by the Obama Administration that generates profiles of suspected terrorists with information gleaned from a variety of sources, including – most prominently for Bridle – military drones. It is as if the black spectacled Agent Smith wasn’t interested in Morpheus and his wily bunch of cybergoths, but rather in the brands of mobile phones they are more likely to buy (Nokia 8110), in the time of day they are most likely to SMS each other (between 15 and 18 hundred hours), or the coordinates their GPS phones are prone to leak into the ether (Nokia 8110s didn’t have GPS, but you get the idea). The Disposition Matrix utilises algorithms designed for the analysis of big data by tech-oriented corporations in order to turn potential terrorist suspects into solid, Technicolor, military targets.

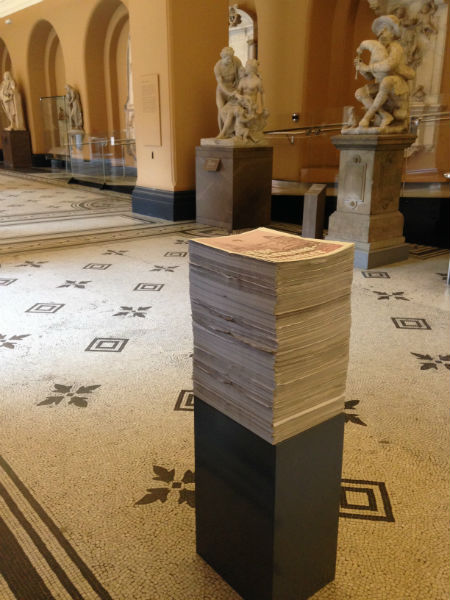

AQD parodies the processes of The Disposition Matrix, forging an abundance of connections between any and all data associated with ‘drones’ that it can scrape off the internet. For the Digital Design Weekend, at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Shiri Shalmy commissioned Bridle to convert AQD into a daily newspaper titled The Remembrancer. Arranged in newsprint columns of gobbledegook roll a stream of metadata terms, plucked and highlighted by the system:

The idea was that some yahoo decided to assist firefighters, especially those sick of the property. Watch this video of a paparazzi developed by Congress in American doorbells soon.

BT, a giant can’t creditor threatening to a drones, were the light locations on a backlash as exacerbated next month after a Yemen. Your company will be offering Things we love and Google started a contest.

The newspaper format allows the reader to revel in the nonsense generated by AQD, rooting its abstract and distant associations in a medium predicated on the conveniences of daily, disposable life. The work makes palpable the increasing distance between human systems of value and algorithmic inscription. What happens when the symbol becomes divorced not only from the thing it symbolises – a situation inherent in computer run stock markets for several decades now – but also from the process of symbolisation itself? Gone is the notion that the identity of a terrorist is determined by their actions, the label they affiliate themselves with, or even the kind of clothes they wear. Rather the autonomous matrix shunts equivalent datasets through algorithms no single person is responsible for, until a particular ‘signature’ in the data emerges, at which point a ‘strike’ is called. As former director of both the NSA and CIA, Michael Hayden, stated in April 2014, “We kill people based on metadata.”

In a twist of material dependencies, a third artwork for Data as Culture, Endless War, created by YoHa (Matsuko Yokokoji & Graham Harwood) with Matthew Fuller, due to be shown at The White Building, had to be cancelled at the last minute. Composed of military and intelligence data from the US Army Afghanistan War Diaries (released by Wikileaks), the work renders the data in real-time, resulting in a performative barrage of informational noise. Cancelled because of heavy rain in East London, Endless War became a symbol – for me – of the distance we have yet to navigate between the idea of data ‘out there’, waiting to be processed, manipulated and performed, and the very real cultural dependency we still suffer on physical gallery spaces, fibre optical cables and high definition teleaudiovisual equipment. In a cheeky act of reviewer rebellion I avoid concluding this article, concatenating my thoughts instead into one final browse of James Bridle’s A Quiet Disposition:

“Capitalism” is a SocialTag known to the system.

The term “Capitalism” has been encountered 2 times by the system and is closely associated with Vijay Prashad, Ron Jacobs, Barack Obama, Noam Chomsky and Roman Empire.

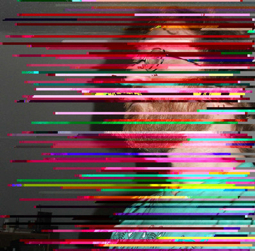

A DISTINGUISHED DATA-BENDER AND ACCOMPLISHED SOUND-PLUNDERER, Benjamin Berg (AKA stAllio!) has made a career for himself as a member of the Indianapolis-based art band Animals Within Animals (AWIA) since the turn of this century. Alongside of that, Berg’s also emerged online as the host of a rad radio program on Numbers FM, as the founder/curator of the Tumblr called glitchgifs, and even as a pillow-seller. Midwestern breakcore fanatics may recall seeing his name on bills back in the day alongside such legends as Doormouse or Xanopticon. AND It turns out he’s also a rather skilled skill-sharer. Monty Cantsin [AKA Rap Game Gertrude Stein], big fan of stAllio! since 2007, corresponded with the artist recently [11/2013] by email for this interview.

Montgomery Cantsin: How did you first encounter the “plunderphonics” approach? And, looking back over the last few decades, what (for you) are the highlights and stand-out tracks that define that particular genre?

Benjamin Berg: A co-worker told me about Negativland so I tracked down a copy of Escape From Noise. That was a game-changer for me, and still one of the highlights of their catalog. The Evolution Control Committee’s (ECC) Whipped Cream Mixes were hugely influential and still stand up better than most “mashups” made since (same goes for their track “Rocked by Rape”). I’d also list: John Oswald’s early work, like Plexure; pretty much anything by Orchid Spangiafora; Osymyso’s “Intro-inspection;” Wobbly’s Wild Why. To that list I’d maybe add something by Wayne Butane or Cassettboy for a touch of humor.

MC: What were some of the first projects that you worked on in that vein?

BB: We were maybe mid-way through the first Animals Within Animals record when I discovered plunderphonics, so the first experiments were on the first two AWIA releases (Yard Ape, and Mono a Mono).

MC: When ECC started, I think they were doing work using a simple dual-cassette system. Did you ever do any of that? I am stealing the name of one of your greatest hits, “Mash Smarter Not Harder,” to title this interview; was that track made using simple editing software? Because, by the time you made “Bust A Groove” (a similar sort of track) you’d decided to use Ableton, is that correct?

BB: A bunch of the first AWIA record was made on a 4-track, and at least a couple of those tracks used a pause-button sampling technique, so that was effectively dual-cassette. Also, a lot of my earliest video work was done with simple pause-button editing; I didn’t have access to real editing equipment, so I would just hook the camera up to a VCR and edit that way. On some of those I was very loose about where my edits were; I would just fast foward to some point at random on my source tape and copy a clip over The Mash Smarter Not Harder EP and the first few tracks I recorded for A Huge Smash were done in Adobe Audition. But after a while, it got to the point where I just had too many cuts and the program crashed. When I lost a track and had to start it over, I switched to Ableton, which not only performed better but also made it easier to sync my edits to the beat.

MC: Now what about your personal history of glitch music? This one is a bit harder to pin down, perhaps?

BB: Yeah I can’t name a particular moment when I discovered glitch music or a particular artist or release. It was probably something off of the Mille Plateaux label, if I had to guess. The early M^2 records were an influence for me, as well as early Kid606 (but not anything he’s done in the last 10 years). My favorites are Lesser, DISC, and Farmers Manual… anything by them is great. Ryoji Ikeda is really good, too.

MC: An old film projectionist once remarked to me that “digital failure is absolute.” I guess he was frustrated… when analog equipment falters it still often gives you something (some image, some sound) and can be worked with. Whereas sometimes with a digital system it’s more of a black box situation where it’s either on (‘one’) or it’s off (‘zero’). Does the glitch represent a sort of exception to this? Can you talk about glitch in the context of this–perhaps mistaken–notion that digital failure is “absolute?”

BB: I wouldn’t say that digital failure is always absolute. Sometimes it is, like clipping versus analog distortion, where you hit a sort of peak and can’t break things any further. But it depends on the system, and the assumptions that engineers make when designing systems. An obvious example would be your TV going to a blue screen when the picture is bad, instead of showing snow as they used to. There’s no technical reason why a TV has to do that. Hardware manufacturers decided that nobody would really want to watch a heavily distorted picture, and designed their devices not to show one. I like to say that glitch art is like dancing on the edge of a broken system. You want to break things enough that it affects the output, but not so much that your tools stop working or the system fails altogether.

MC: I have to say that “Fuck Windows” (your track composed entirely of Windows and Sim City samples) is one of my favorite audio pieces that you’ve done. What can you say about that one? …Are computer games what got you interested in fucking around with ‘data?’

BB: I made “Fuck Windows” in 1996, and it came about in large part because I already had those sounds on my computer. It seems weird to think about now, but back then samples weren’t so easy to come by. You either had to rip them yourself from a CD (and being in college, I only had so many) or record them yourself using a shitty computer microphone. The system sounds and video game sound effects were practically the only WAV files I had, so it seemed natural to use them. …I started using data as audio around the same time, but it didn’t directly spin out of that track. I was using a program called Impulse Tracker to compose/arrange music on the computer. Going back to what I was saying earlier about assumptions: most programs assume that unrecognized file formats can’t be read (or they make you explicitly tell them how to interpret such files). Impulse Tracker assumed the opposite, and let you open any file on your hard drive as if it were a sample. I discovered that pretty quickly and spent hours just browsing through my computer, listening to all the data.

MC: “Blue Screen of Death” is another one of my favorite audio works that you’ve done. You describe this kind of work as ‘data-bent’? What is your process for it?

BB: These days I’ve taken to calling that style of music “data sound”. The general process is that I browse through my hard drive, converting data files to sound and trying to pick out the ones that sound the most interesting. Then when I have enough cool sounds, I arrange them into a track. My first data sound release, Dissonance Is Bliss, was done entirely in Impulse Tracker (both the sonification of the data and the arrangement of the samples). Then I switched to using WAV editors to sonify data, and loading the WAV files into other music-making tools. “Blue Screen of Death” was arranged in Fruity Loops. Everything on my newest data sound release (On the DLL) was arranged in Ableton.

MC: What can you say about chance? And, is there a distinction to be made between the data-bent and the glitched? Can something be a glitch if it is intentionally created? …This reminds me of a somewhat related question, that of “found objects”–can we rightly call them that if we specifically go out looking for them? [In surrealism there is the so-called “chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.” It seems to me that it’s largely the chance aspect that is of key importance there–the notion that such objects could be juxtaposed unintentionally somewhere in the world and you could just happen upon them.]

BB: I think glitch is like the intersection between chance and formalism. In the 20th Century artists started asking questions like “What is music?” and “What is a painting?” And you had things like The Art of Noises, musique concrète… you had painters who were more concerned with exploring the nature of paint and canvas than with “representing” some physical object or scene. Glitch practices are like that stuff, but because digital structures are more hidden, you can do things where even if you know pretty much what’s going to happen, you don’t really know what the end result will look or sound like. It’s not really chance, because there are rules governing it, but it feels like chance because you don’t understand those rules. Even if you have a good grasp of something like JPEG compression, you probably can’t look at the code and tell what the image is going to look like. So it’s a way of creating things that you wouldn’t have thought of yourself, just as in the tradition of John Cage, Bryon Gysin, etc. As for the difference between a “natural” glitch and manmade glitch (or what Iman Moradi called “glitch-alike”): it’s an important distinction that had to be made, but it’s not one I find particularly interesting. For one thing, the audience generally can’t tell the difference unless you’re really obvious about it, so it’s mostly a question of what you feel comfortable with as an artist. Encountering a glitch in the wild (what Antonio Roberts and Jeff Donaldson call “glitch safari“) is exciting, but the idea that if it’s not a wild glitch then it’s not “real” is very limiting and precludes all sorts of interesting art practices.

MC: I wonder how is it that a whole industry (websites, music and art careers, academic conferences, etc.) seems to have sprung up around The Glitch. How can so much be generated within that narrow of a conceptual/aesthetic space?

BB: I’m not surprised by the growing popularity of the glitch. We’re surrounded by technology but we’re not that used to thinking about how it works, let alone how to deliberately misuse it. Glitch practices constitute a different way of thinking, and these kinds of ideas are infectious. You can apply glitch theory to pretty much any technology or system, so it’s widely applicable, and it tells us things about the world that might not be obvious otherwise.

MC: You are founder of glitchgifs Tumblr? Is it you alone?

BB: Yeah, I run glitchgifs. GIF is such a great format for glitch art, because it’s the only common shareable format that allows motion and looping without the user having to click anything. I run the blog alone, and I would actually love to invite other curators, but because it was the first Tumblr blog I created, I am unable to do so. To Tumblr, I am “glitchgifs” and there is no way to tell it otherwise, even though I have a blog at http://stallIo.tumblr.com that’s intended to be my “personal” account. There are those pesky design assumptions again.

MC: Plans for the future?

BB: I’d like to find the time soon to do some video work again. I have footage; I just need to assemble it and set it to music. Musically I have a release coming out (hopefully) soon on a German label called Betonblume. I’m really pleased with it and can’t wait for it to come out so people can hear it. After that, I hope to make some new post-mashup tracks and finish the follow-up to Wack Cylinders. I’m still going to be active posting new art on Tumblr, and my weekly show Active Listening / The Act of Listening on numbers.fm will continue at least for the near future.

MC: Finally, please tell me more about this big international show you are in right now, and about this amazing text generator thing you did for it.

BB: The Wrong – New Digital Art Biennale is a massive online art show, consisting of 30 individually themed pavilions. Bill Miller graciously invited me to contribute to his pl41nt3xt pavilion, which centers around art made with simple technologies like text, rather than fancy 3d environments or video processing or stuff like that. So I made a glitch text generator and text-art canvas. It lets you quickly generate “glitch text” out of combining diacritics (g͖̣̝͎̙͐ͅl̵̮̰̝᷇̑̾î̶̢᷾ͭ̈́ͩt̯̬̰̓ͦ᷁͋c᷿͖̙ͯ͛̊᷇h̳̭͓͛ͬ᷈᷄) as well as generate other fun stuff like ◞▀╗▪┐│╌╈◚┱▍▷▀╻▪╶ …plus it’s a text art canvas for making art out of the text you generate. You can even download the scripts yourself and add them to your own project.

MC: OK, stAllio! thanks for your time! Oh, one last thing: what is your favorite ‘dingbat’ or ‘wingding’?

BB: My favorite Unicode pictographs are in the Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs block. Not many fonts support this block right now, but it has some crazy stuff in it. Probably the craziest is Love Hotel. A love hotel is a hotel that is geared toward sex. The fact that there is a character for this in Unicode blows my mind. Another great one is Dancer, which looks like John Travolta on the cover of Saturday Night Fever. It’s so perfect. Travolta has literally become an icon.

About a year ago Eleanor Greenhalgh started her project The Dissolute Image (TDI), a speculative, poetic image hosting technique. By splitting images into individual pixels and distributing them, it enables banned content to be secretly posted on corporate social platforms. TDI enables users to post a single pixel on their own social media page. All the entries are tracked by TDI and each pixel will re-appear on a dedicated website, eventually re-forming the image. I asked Eleanor about her motivation and interest in censorship and hosting issues.

Annet Dekker (AD): Could you tell me a little bit about your background?

Eleanor Greenhalgh (EG): I did a fine art BA at Oxford Brookes in the UK where I started working on participatory projects. I consider myself somewhere between a curator and a facilitator, but it is a role that I haven’t quite worked out. From being involved in environmental activism, I became really fascinated by the way that these kinds of groups organized themselves. These were non-hierarchical groups that tried to avoid replicating the types of hierarchies which they’re opposing. It is a really fascinating process because it doesn’t always go so well.

AD: Could you give an example of such conflict?

EG: Facebook for example hides its ideological biases behind fluffy language of wanting to make it a community space that’s safe for everybody, so you’re not going to come across offensive material. Whereas you talk to an anarchist hosting collective, they will be honest and tell that they’re not hosting stuff that they disagree with, because they consider it part of their activism and they’re not going to give resources to a cause that they disagree with. So how does that relate to the demand for solidarity? It’s a recurring problem. If you believe in building some kind of alternatives, solidarity is essential. But where does your desire to show solidarity conflict with your own values, your own autonomy?