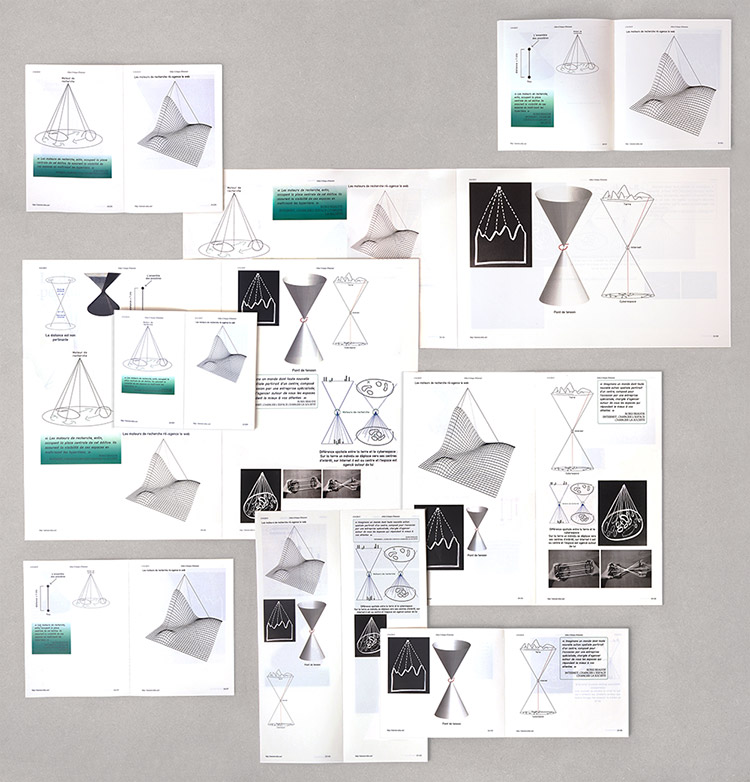

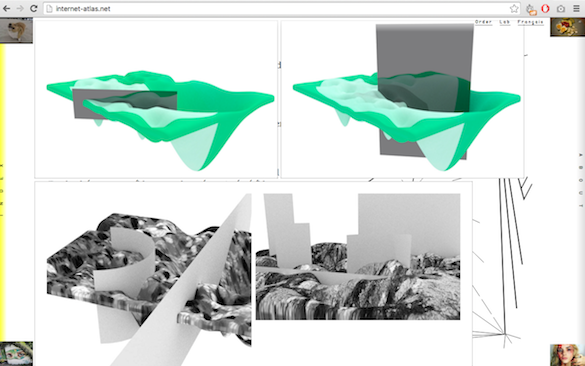

The Critical Atlas of the Internet, Louise Drulhe’s latest project, is a virtual and physical exploration of the Internet space. The implications of our physical actions in ‘real-time’ are not only timeless in ‘cyberspace’, but also constitute the making of an obscure Internet architecture every time we browse the web. The Atlas itself is an enveloping notebook of Drulhe’s discerning methodology in desiring to represent the geography and architecture of the ‘unseen’ Internet territory. Initially, a graphic designer, Drulhe’s practice has meticulously evolved into including cyber-spatial analysis. She yearns to understand the sociological, political and economical issues that appear online or are exasperated by an online presence – ‘a territory we spend time in without knowing its shape’. The Critical Atlas of the Internet, by being parted between fifteen different hypotheses, sheds light on matters such as the monopolisation of non-physical spaces, the possibility of encumbered networks and the potential forms of the Internet.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Drulhe, where she clarified certain distinctive matters that arise from reading or looking at the virtual form of the Atlas online.

CS: In 2014, Google measured 200TB of data that they claim to be just an estimated 0.004% of the total vastness of the Internet. Initially, the Atlas perceives the Internet through many geometric shapes such as cones and spheres. Is this your approach to establishing that the Internet is an infinite space of shared connections and motion? If this is the case, do you believe it is immeasurable?

LD: I will probably get back to you with a better answer to this question in a few months… I am starting an art residency in Paris at La Paillasse, and I will study the question: “can we measure Internet?”. I am curious to see the best way to represent the Internet: to count the data or to measure the borders. I haven’t started this research yet, but I will look for the best unit of measure to calculate the dimensions of Internet territory: meters? Litres? Percentages? Data traffic? I wonder how to define the “size” of a website. If we look at Google.com, it’s only one webpage, so does this mean that Google is smaller than a regular shopping website that might have thousands of pages?

With the fourth hypothesis of the Atlas, “The Geographic Relief of the Internet”, I tried to represent the «size» of Internet platforms. Their size is actually based on the concentration of the activities they host. The Internet giants try to saturate and incorporate as much territory as possible. Google (now called Alphabet) possesses Chrome, Gmail, Android, Google +, YouTube, Blogger, Google Map / Earth / Street View, Cloud, Nest, and Google X… to cite a few. Internet giants are almost raging an online war to monopolize most Internet territory. I think the next virgin land to conquer is the Internet of Things. The map of this 4th hypothesis is based on a ranking by Alexa’s Top 500 Global Sites. What I would like to do next is to measure this representation.

CS: Extrapolating from your claim that the Internet is a single point at the centre of the globe, what would the repercussions if that space were to be encumbered? Can a network not be encumbered?

LD: It’s true. A reticular space cannot be encumbered, I guess. Facebook.com, for instance, is getting more and more popular, but the site works perfectly; you don’t feel crowded situations on Facebook. If Facebook were a physical public square and 1 billion people met there one day, the situation would be really problematic. On Facebook, you never see the crowd.

In the Atlas, I quote Boris Beaude on this idea “The growth of reticular networks, unlike that of cities, increases their interaction potential without boosting their internal distances. Regardless of the network size, the distance between its respective parts is potentially non-existent. Facebook can host 800 million people without affecting its interaction capacity.”[1] This is what he calls “reticular coalescence”.

[1] Boris Beaude, Internet : “Changer l’espace, changer la société“. 2012.

CS: You build your thesis on the hypothesis that Internet space does not require distance; each component is of equal distance to the other. Otherwise, one click away. Whilst this grants no special status to any person’s ‘search’ to being more important or unimportant, aren’t these ‘search results’ always altered depending on the search engine? For example, untracked browsers such as Tor or extensions on Chrome such as ‘Hola’ have the capability to displace a user from their current location and thus materialise a different order by which results appear to us.

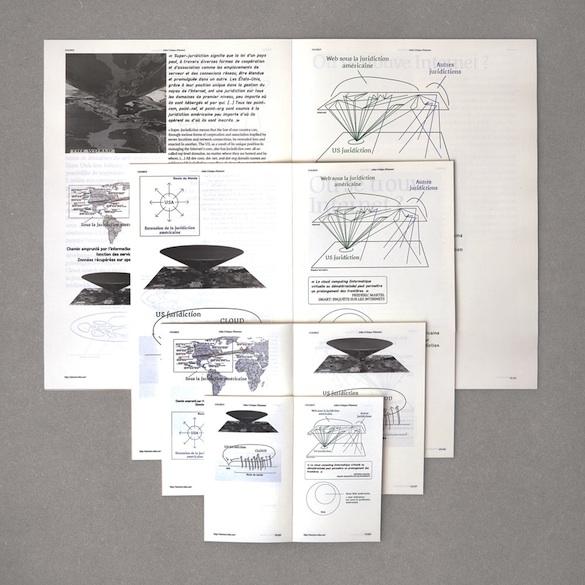

LD: I wrote that the search engines “control Internet architecture” and “distribute the space”. Because almost everyone uses Google, we can assume that Google is the one that controls Internet space so if you use another search engine, like “DuckDuckGo”, you will access the web through a different architecture. But “Tor” and “Hola” are not search engines. “Tor” is a network that enables anonymous communication, and “Hola” is a VPN.

By using a VPN, you can bypass censorship. By changing your localisation, the VPN will give you access to another web. There are as many Internets as there are legislations. This idea is represented in the hypothesis, “A Global Object Projected at the Local Level”. The Internet is global, but we use a national projection of the global network. If you are in China, with a VPN, you can browse the Romanian web and access websites censored by the Chinese government. VPNs also enable anonymity, but that’s another aspect of it.

CS: Another one of your hypotheses places us (the users) at the Internet’s centre, constructing the space around us as we move through it. Indeed, the Internet meets our individual needs. Would you, therefore, account for it more as a product – the world’s only flawless consumer good?

LD: Here, I would like to draw your attention to another aspect of my research. If we look at the Internet as a consumer good, it’s probably the first that actually turned consumers into products! In rephrasing one of Mike Edgan’s statements, Jason Fitzpatrick says, “If you are not paying for it, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold”. The personal data that are generated through users’ browsing are the new “petrol” of the oncoming economy. And in this particular economy, we won’t be the consumer anymore!

CS: In early forms of the Internet, ‘cyberspaces’ were decentralised. Now, as the Atlas conveys, data is concentrated within the hands of a few ‘heavy players’, illustrated as ‘network nodes’ of various weights burying themselves within the Internet’s surface. Since most of the ‘network nodes’ come from the west, would you consider the Internet to possess a particular Westphalian sovereignty?

LD: The centre of gravity of the Internet is clearly the west, but not, in my opinion, the west as a whole. The US has a dominant position for multiple reasons that I detailed in the Atlas. The Internet’s centre of gravity is defined as “the weight, concentrated solely at one focal point, instead of being distributed over several different points”, a focal point which is undeniably Silicon Valley.

CS: I’d like to ask you about the visual representation of your online Atlas. In particular, about the rigid protrusions of space, you used to convey the ‘splinternet’ and the humorous intrusions of Hilary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, among other seemingly unplanned objects such as fried eggs. Could you comment?

LD: We often imagine the Internet as a single Cloud and a unified territory, but this is wrong. Some multiple limits or frontiers exist online. Some of them are really clear, like the Great Firewall of China: the wall of censorship that divides the Chinese Internet from the rest of the Internet. Another obvious frontier is the limit between the deep web and the surface web. But the frontiers that interested me most were the ones that nobody seemed to pay attention to. The limits are defined by private networks, such as Facebook. People with a Facebook profile never see the frontier because there are always logged in. But when you do not have the password, Facebook is closed, even if some pages are left open to attract you. Their goal is to make you join the private network.

CS: And the unsystematic quirks?

LD: Each time the website loads, the images are automatically taken from the emblematic forum “Reddit”, defined as « the front page of the Internet ». Those images work as timestamps in the Atlas; you can find them at the 4 corners of the website and on the books. The Internet is a perpetually changing space, constantly evolving. It was important for me to bring a timestamp to my Atlas. In addition, these images are symbols of the Internet culture; the Internet meme: viral images spreading through the web and overflowing onto my Atlas.

CS: I’d like to address your citing of Introduction: Rhizome by Guattari and Deleuze. They claim that a rhizome can be connected to anything other and must be’ and therefore does not follow the same arborescent structure of a book or tree. However, as mentioned before, there are arborescent nodes within the Internet itself – the ‘heavy players’. Do you believe this may distract multiplicity or enhance the creation of territories within the Internet? Would you also support that in the case of a rupture, where a rhizome breaks or one of the arborescent nodes fall apart, another node responds to replace as if it was always as such?

LD: Yes, that’s a good comparison. I believe that the heavy players saturate and erode Internet space. This idea is supported by the fact that each company creates a personalized arborescence that is really difficult to connect to by developing its own patterns or ecosystems, like the arborescence of a tree. In this idea, they are breaking with the original shape of the network and its interoperability.

About the rupture, actually, I am not sure. If a node disappears on the network, another node will not necessarily be replaced. If a web page goes offline and at the same time a Facebook page has just been created, the new node (from Facebook) does not take its place. The new node is actually created within the Facebook network. And to refer to my hypothesis about the geographic relief of the Internet, the node opens on the slope of a dominant gap.

CS: As a final point, there’s a particular passage from Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation which I find can be quite relative when considering the structure of the Internet:

“Abstraction today is no longer that of the map, the double, the mirror or the concept. Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map nor survives it. Henceforth, it is the map that precedes the territory – the precession of simulacra – it is the map that engenders the territory. If we were to revive the fable today, it would be the territory whose shreds are slowly rotting across the map.”

How would you interpret this if we took into consideration Internet territories?

LD: Most people do not consider the Internet as a territory. This idea of cyberspace is a bit old-fashioned. But, I think it is still pertinent today to study the Internet as a real space.

The way we access representations of the Earth today is really magical. Google provides easy access to an extremely precise representation of the Earth through satellite images and maps… But for the territory of the Internet, it’s the opposite. Even if there are a few maps of the Internet, there are no basic tools to map the web. The territory still precedes the map. I would love to see what a Google street view of the Internet looks like!

20 Digital Years Plus

Station Rose

Nurnberg 2010

ISBN 9783869841113

“Twenty Digital Years Plus” is a softback book that presents and contextualises the art of Station Rose (Elisa Rose and Gary Danner) from 1988 to the present. Its gatefold cover conceals both a CD and a DVD which provide audio and video to complement the static images and texts, and carries an endorsement from Bruce Sterling on the back cover.

The book starts with a series of essays before presenting an illustrated history of Station Rose. Those essays approach Station Rose from some refreshing and unexpected angles to make a convincing claim for their art historical interest.

Peter Noever writes in the book’s preface that “Media art is both an art form and a way of life for Station Rose”, a claim that the evidence of the book more than supports and that I think is key to why Station Rose’s art is so interesting. The book functions as a mid-career retrospective, and Noever suitably sets the themes of achievement and continuity.

Vitus H. Weh’s essay explains how Station Rose got their name and puts their LoginCabin project into the context of German post-cold-war architecture and the sociology of the Wild West. We are a long way from the early 90s view of the Internet as a new frontier, but despite its critics that view was not uniquely tied to American society and provided a liberating impetus to individuals who didn’t always subscribe to the Californian Ideology.

Hans Diebner’s critique of net art and activism brings a thought-provoking scientific, techno-art historical and philosophical critical literacy to bear on Station Rose and the artists and activists that he contrasts them with. Diebner weaves together diverse conceptual strands into a coherent critical case without any resort to jargon, and it’s worth thinking through how his case affects our view of net art in general as well as Station Rose’s position within its history.

Didi Neidhart’s interview with Rose and Danner provides context for and insights into how the pair create and conceptualise their work, and how their art and music relate. Station Rose emerge as the product of cultural engagement and lived history rather than academic fashion.

Gabriel Horn writes from a curator’s point of view about the future shock of working with Station Rose in 1991, in contrast to working with them in 1999 when they are part of an intermedia exhibition.

The bulk of the book is an illustrated history of Station Rose. They started out in 1988 as a multimedia lab in Vienna complete with 16-bit Amiga computer. In November 1988 they went online for the first time at the Sampling conference they held in Vienna, having already adopted the technology and concepts of sampling into their art and performance. Since then their work has taken the form of CD-ROMs, live streaming media, live multimedia performance, Internet homepages, CDs and vinyl with Sony records, books, TV shows, multimedia installation, webcasting, lecturing, teaching, and a shed.

Station Rose also create memes, or language, such as the statement quoted by Bruce Sterling on the back cover that “Cyberspace is Our Land”, the much needed identification of the “Digital Bohemian Lifestyle” and the increasingly paradigmatic condition of being “private://public”. Even in an age when the concept of multimedia has largely been absorbed by the Internet their work crosses and assembles different media.

Much of Station Rose’s digital art has the not quite glitch aesthetic of overlayed pixellated form in shallow depth that any serious history of digital art needs to account for. But the cubicles, huts, pillows and panels of their installation work have the same aesthetic. Station Rose’s work is in itself a history of digital art over the last two decades. And this digital art is always in dialogue with physical performance and physical structures, the virtual in dialog with the real to illuminate each other.

In Neidhardt’s interview, Danner says of Station Rose that “We are quickly bored with things as soon as they become mainstream.” Boredom with the content and products of digital media is the friend of the scheduled obsolescence and cultural amnesia of market mass media. But boredom with the form of and the means of creating digital media can also serve to motivate the creation of successive alternatives to it.

Over the last 20 years the Internet and digital media have gone from being a novelty to being socially and economically pervasive. This rate of change, and the constant promotion of different visions of what the Internet is for by different institutions, mean that our relationship with the Internet has come to be in plain sight. Artists can usefully depict and help us conceptualise that relationship, particularly those artists who can use the digital media that has been drawn into the Internet and become no small part of its operation.

Station Rose are such artists. Their art has the quality of being both the product and producer of lived experience in the age of digital media. It refracts the logistics and glitches of the Internet through the prism of contemporary art’s deceptively low-fi rummage sale aesthetics to present them as objects of contemplation. When digital media was new this served to make them accessible to an unfamiliar public. Now that digital media are pervasive to the point of invisibility, this serves to make them visible again as objects of contemplation and to afford the viewer a critical distance from them.

20 Digital Years Plus is an engrossing, thought-provoking presentation of the ongoing development of Station Rose that makes clear the value of their constantly enquiring relationship to ever changing technology.

(With thanks to @MarkRHancock)

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.