“In a world full of conflicts and shocks,” has the past year become the, arguably, most standardized introduction, preempting, in an almost doomsday manner, articles, political speeches and curatorial statements alike. The world has turned Political (with capital P) and even the most mundane event is quickly made part of current politics, which in turn, seems to occupy a space somewhere between reality TV and satire. One feels the same dreadful fascination as when watching accident videos on YouTube; with eyes hypnotically fixed to the screen as we observe our world digress into an ever-growing state of chaos. A general unease can be traced throughout the world, and even the most apolitical communities are mobilizing at each side of the spectrum, in the desperate search for ways to overcome the immediate and underlying threats-at-hand.

It is within this urgent search for solutions, that this year’s Venice Biennale positions itself. The 57th biannual gathering of today’s most prominent instances of Contemporary Art, offer, under the lead of curator Christine Macel, its own proposal as to how we might address our sometimes-hopeless situation. And, perhaps surprisingly, we are in fact given an answer, which eschews the otherwise often-ambiguous and overly-complicated musings traditionally marking the Art World. Within the manifesto of the biennale, immediately greeting you as you enter the Giardini venue located South of the City, Macel calls for a return to humanism, expressing the need for a new-found believe in the power and agency of humans. And not just any human; particular emphasis is given to the Artist, the persona through which, supposedly, “the world of tomorrow takes shape.”

Structurally, the role of the artist is explored over the course of nine chapters, spanning themes as distinct as ‘earth’, ‘colors’ and ‘time and infinity’. Each, we are told, does not only account for the artist’s practice in isolation, they further set out to investigate how such creative acts resonate and bring about change in the world.

One misses immediately this latter concern within the two first pavilions Artists and Books and Joys and Fears. We are invited into the space and mind of the artist, in what quickly becomes an introvert, almost nostalgic account of the studio, presented here as a place which escapes the neoliberal ideals of progress and productivity. One senses an immediate contradiction, being surrounded by pieces which literally embody the immaterial value so indicative of modern capitalism.

This haunting sense of conflict is occasionally placated, if only because many of the individual pieces go further than the prescribed curation, integrating a sense of criticality in their exploration of the art practice. As in the breathtaking video by Taus Makhacheva, in which a tightrope walker carries paintings between two cliffs, over a lethal fall, seemingly free, while caught in a pointless, repetitive and dangerous act, dictated by guidelines which goes beyond his immediate control. Or in the, now infamous work, by John Walter, Study Art Sign, which appropriates the language of advertisement in simple catch phrases such as “art – for fun or fame,” and in doing so, highlights the entanglement of any artistic act with commercial viability.

A 20-minute walk, and the habitual crossing of at least 5 Venetian bridges, brings you to the Arsenal pavilions, and the home of the next 7 chapters. The first two of these, Commons and Earth, are (at least superficially) more successful in exploring the link between the artist and the world at large. The exhibited pieces are centered around the creation of community or situations. They echo in this sense the much-disputed Relational Aesthetics as advocated by Nicolas Bourriaud, which defines contemporary art, as one of “interactive, user-friendly and relational concepts.”(1)

What Bourriaud and the Biennale both seem to overlook, is the inescapable mediation and exclusivity of artistic acts, despite any willingness to advocate inclusivity and openness. Because, let’s face it, none of the presented practices can be equaled to just another social situation – each and single one has been extensively documented, carefully edited and analyzed, to finally make their way into one of the most prestigious temples of contemporary art: The Venice Biennale anno 2017.

This does not make them insignificant, it simply means that one cannot feign apparent neutrality, as the emphasis on ‘anthropological approaches,’ seems to suggest. In fact, the more ‘honest’ pieces are the ones which embrace such mediation, exposing it, rather than hiding it behind a layer of innocent interaction. This is done brilliantly in the video piece of Charles Atlas, A Tyranny of Consciousness – an epic compilation of sunsets, countdowns and disco. The groovy lyrics, ‘You were the one, I blew it, it’s my own damn fault,’ sung by the iconic drag queen Lady Bunny, is given new meaning in the context of environmental, human-provoked disasters.

This is done, while avoiding any moralistic undertones. Rather, the piece dares to reflect the ambiguity which defines the actual human-earth-relation, and through this, overcomes the simplified ‘if we all work together it’ll be fine’ attitude, otherwise permeating the majority of the exhibited work.

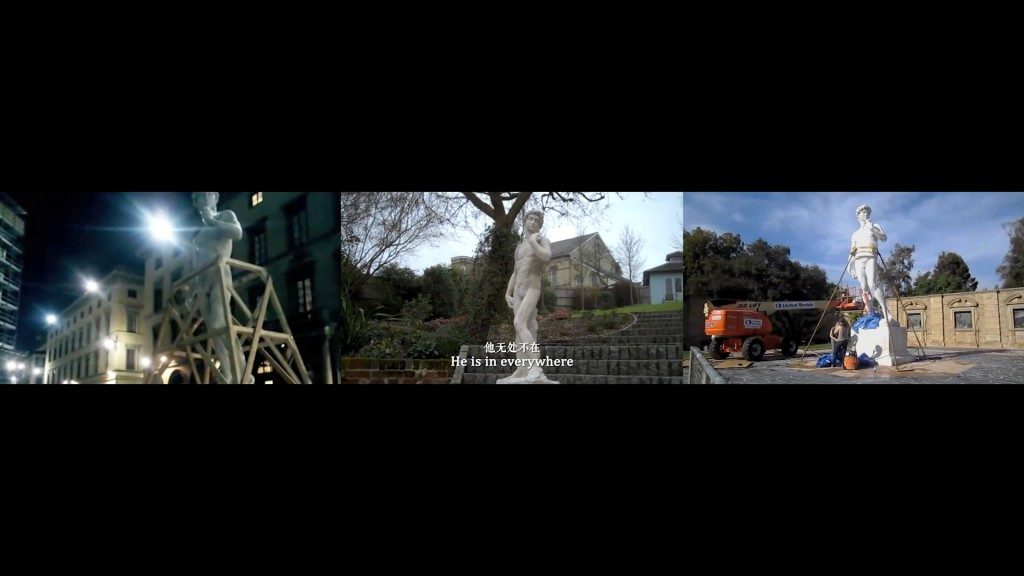

Within Traditions, the chapter following, the most successful pieces are similarly those which allow for complexity and move beyond an often much-too-obvious contrasting of the old with the new. One notable example, is the piece by Guan Xiao, which traces the famous statue David by Michelangelo. In bringing together numerous amateur-looking clips capturing this iconic figure, she humorously points to how objects ironically become invisible, through our extensive documentation of them; as hidden behind the connotations and expectations which come to shape the way we perceive our cultural heritage.

On entering the next theme of Shamanism, the first piece which meets the visitor is by Ernesto Neto – a tent-like installation made up of robes, under which guests are offered a place to rest. The otherwise beautiful piece come to look like a feature of Burning Man, with hippie-esque slogans such as ‘with love and gratitude to mother earth’ or ‘’war is not good, gold is life,“ covering the surrounding walls.

What Macel here wants to explore is the artist as magician or healer. While attempts of healing is sympathetic (and needed), such efforts are undermined by, a once again, rather naïve approach. It seems as if the striking similarity to the peace-promoting, but notoriously exclusive, festival is not only aesthetic. There is a failure at acknowledging the difference between giving the (very specific demographic of) biennale goers a place for momentary reflection, and the large-scale healing announced in the curatorial statement.

This pseudo-commitment to seventies politics carries over to the Dionysian Pavilion, which ‘celebrates the female body and its sexuality’. The decision to dedicate a pavilion specifically to female artists and femaleness implicitly tells us that

a) womanhood is still something distinct, which should be explored separately from other identity politics

b) women artists need their own space, neatly separated from the rest of the pavilion (which is, interestingly, dominated by male artists)

We see here not only a return to humanism, but the ugliest of humanisms, one which still insists on highlighting an assumed distinction between manhood and womanhood. Such essentialist undertones are only enforced by the first part of the pavilion which greets you with pastels, vaginas and a propensity for weaving.

While the theme might be questionable, we do, while moving through the pavilion, find some incredibly strong pieces, which insists on addressing the individual in its many nuances and confused nature. This is particularly present in the all-encompassing installation/sound/performance work of artists Pauline Curnier Jardin, Mariechen Danz and Kadar Attia.

This far-reaching journey culminates in the chapters Colours and Time and Infinity which bombastically sets out to explore the way artist come to influence that which exists outside and before a human sphere. Within both pavilions, there is a distinct failure at acknowledging the specificity of the individual works, which, besides from their formal qualities, seems to have little to do with either Colours or Time. Once more the curation, ironically, overshadows, rather than enhances, the complexity of the individual works at stake.

It is symptomatic of the, perhaps biggest, misunderstanding of this year’s biennale: That a return to the artist, or the human more generally, is what will allow us to understand and surpass our current state of crisis. It seems to overlook that our anthropocentric attitude is what originally brought us into trouble. Just as the individual pieces of art are diluted by insisting on the narrow focus of the artist, so does humanism distract us from the complexity of the world in which the human is only one part out of many. It simply seems outdated to return to the human-figure, conceptually broken by critical theory and practically threatened by developments in AI. Rather we need to accept, as many of the brilliant pieces do, a state in which humans are not in control; which allows for spaces of ambiguity and contingency. We do not need a return to humanism. Rather, now is a time to be humble, to look outside of humanity and think beyond that which already was, and never really worked in the first place.

So ArtForum have launched a special September issue investigating the, lets say broader, relationship between new media, technology and visual art.*

Of worthy mention is the essay Digital Divide by the art world’s antagonistic critic of choice Claire Bishop, a writer whom a little under 8 years ago, deservedly poured critical scorn over the happy-go-lucky, merry-go-round creative malaise that was Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics and all of the proponents involved. Since then Bishop’s critical eye has focused on the acute political antagonistic relationships, within the dominant paradigms of participatory art and the concomitant authenticity of the social.

In Digital Divide, Bishop asks a different question, and its delivered even more bluntly than usual. Why has the mainstream art world, for the most part, refrained from directly responding to the ‘endlessly disposable, rapidly mutable ephemera of the virtual age and its impact on our consumption of relationships, images and communication.‘ This is not to say the practices of mainstream artists do not rely on digital media (in almost all cases, it now cannot function without it), but why hasn’t the shifting sands of digital culture been made explicit? In Bishop’s words;

“[H]ow many really confront the question of what it means to think, see, and filter affect through the digital? How many thematize this, or reflect deeply on how we experience, and are altered by, the digitization of our existence?”

Clearly, there are exceptions and she mentions three examples by art stars Frances Stark, Thomas Hirschhorn and Ryan Trecartin which flirt here and there with digital thematisation. Conversely artists who once specialised in digital art, Cory Arcangel, Miltos Manetas – to name two very famous examples – have previously broken out into the mainstream.

But for Bishop, there is of course, “an entire sphere of “new media” art, but this is a specialised field of its own: It rarely overlaps with the mainstream art world (commercial galleries, the Turner Prize, national pavilions at Venice)” – (one could add art fairs here). But nonetheless “these exceptions just point up the rule“. Bishop’s focus is on the mainstream and, moreover, she contends that “the digital is, on a deep level, the shaping condition—even the structuring paradox—that determines artistic decisions to work with certain formats and media. Its subterranean presence is comparable to the rise of television as the backdrop to art of the 1960s.” True enough, this structuring paradox is an implicit problem with the mainstream art world, but thats not the problem tout court.

From the responses I’ve read both in the article comments and in subsequent blog posts, a particular issue has been marked with Bishop’s statement that “new media” art is a specialised field. Whilst it doesn’t qualify as a dismissal, one could certainly suggest that Bishop is partly guilty of the same disavowal she throws at the mainstream art world when she relegates this sphere as an ‘exception’. In a blog-post response, Kyle Chayka makes a similar point; “Bishop understands that digital technology forms a seedbed for art as well as life, but fails to uncover the artists who are already critiquing that context.” I’m not a Lacanian, but maybe this is a symptom of something.

If mainstream art is ‘the rule’, (and I’m insinuating ‘the rule’ as anti-metaphor here) perhaps ‘the rule’ isn’t worth paying attention to, considering that the new media art exception is too much of a ‘specialisation’. In as much as one can only agree with Bishop’s call for mainstream art’s negotiation with digital thematisation, has she not missed the same aesthetic questions already posed and re-composed in this exceptional sphere? Why should the qualifier of the mainstream be such a factor of importance here? Why not cut off the need to reconcile digital thematisation with a set of historical, and commercially ideological principles which may not take kindly to the more ambitious and darker questions that the social and political arena of global digitalisation have thrown up. This is not to say that Bishop isn’t seeking those questions nor does she wish to reconcile those principles, but the specialised sphere of ‘new media art’ may quench the questions she herself raises.

Case in point: all Bishop would have needed to reference is something like the Dark Drives exhibition for the transmediale festival earlier this year; the tag line “uneasy energies in Technological Times” sums up her main descriptions of a digital epoch quite nicely. For instance, the artist group Art 404’s 5 Million Dollars 1 Terabyte, renders explicit one subset of the absurd, copyright, exploitative logic of proprietary software, by saving one terabyte’s worth of unlicensed software onto a single hard drive. Next to it was JK Keller’s idiosyncratic piece Realigning My Thoughts on Jasper Johns, which showed off a glitchy, abstract bastardisation of a Simpson’s episode Mom and Pop Art – regurgitating haggard mainstream perspectives. Crucially the success of the show was down to the implicitness of the exhibition’s technical triumphs – where technical jargon is often touted as a reason for the mainstream’s averted gaze. Whilst the viewer didn’t need to know the technics, but a richer understanding emerged should they have wanted to know.

There isn’t any need to clog up this article with a bottomless plethora of pieces from other equally important exhibtions and shows (I’m sure many others are better qualified in doing so); my point here, is that Bishop cannot relegate new media art as an exception to the rule, when the digitalisation of media is becoming the rule, which she herself explicitly admits. Choosing to focus on the failure of the mainstream in this arena gives the essay a healthy line of questioning, but in relegating an entire sphere which has – for some time – repeatedly dealt with these questions and more, it raises what is effectively a pointless query. To be fair to Bishop, she isn’t trying to force a fecund translation of new media with mainstream values, but looking for methods where digitalisation can instigate the change of those values.

Granted, Dark Drives is one major show in a major Berlin new media festival – the top of a very extensive collection of disparate voices and influences – but it inadvertently highlights a salient thought. What if Bishop’s call to bridge the ‘Digital Divide’ was actually met by a new generation of artists thrust into the mainstream, where digital themes were translated into its own methods of commercial production? We’ve gotten over the myth that ‘virtual’ commodities are unmarketable, so it’s not as if I’m being negative for the sake of it. Where would this leave festivals like transmediale, or not-for-profit collectives like Furtherfield – how would they respond? It’s an uneasy question, one which for speculative purposes cannot be answered quickly at present, if at all.

In the throws of conjecture, there is perhaps another division at play here. Towards the end of her essay, Bishop makes a reference to the difference between the non-existent embrace of the digital medium today, and the rapid embrace of photography, film and video in the 60s and 70s.

“These formats, however, were image-based, and their relevance and challenge to visual art were self-evident. The digital, by contrast, is code, inherently alien to human perception. It is, at base, a linguistic model. Convert any .jpg file to .txt and you will find its ingredients: a garbled recipe of numbers and letters, meaningless to the average viewer. Is there a sense of fear underlying visual art’s disavowal of new media?”

This is a division which is even more striking; more aesthetically and philosophically significant in comparison to marketable rules and unmarketable exceptions. I think Bishop is really on to something when she chastises the hybrid solutions of old media nostalgia, evidently favoured by the market and contrasts it to the alien nature of code, but it’s not without problems.

Some may consider there to be nothing inherently alien about digital media; many artists, who also work as programmers and write, design and engineer artworks together with code without any recourse to an alien nature (however I vehemently disagree with the notion that code be solely reduced to human production, but it must be pointed out) Likewise, any 90s utopian reading of the ‘digital revolution’ is mired from the start, once you take into consideration, closed proprietary devices and services which falsify other meaningful alternatives (one only needs to trace the important work of the Telekommunisten art collective to realise how advanced these questions are, in what is supposed to be a specialised field).

If there is a fear underlying visual art’s disavowal of digitalisation, it’s not just a critical bemusement of code, but of the material which composes computational media; wires, LCD screens, motherboards, caches, firmware, sorting algorithms. Bishop’s call for mainstream contemporary art to be aware of its own conditions and circumstance is admirable, but unless art can actually get its hands dirty with the material processes of new media and more importantly the underlying computational conditions concerning the digital (because thats what it is), the project of explaining these circumstances will be quagmired from the start. It’s not enough to explain ‘our changing experience’ with computation, but to explain the experience of computation in itself.

But for now, lets keep the divide going, not least because antagonisms are fun (Bishop should know), but because the contemporary digital arts are not hindered with the burden of seeking the mainstream’s attention. They can get away with a lot more as a result. Digital or Computational art needs to be cheaper and nastier, as the artist’s tools of use are getting increasingly dirty with critical engagement and proflierfation of code (one cannot avoid mentioning Julian Oliver et al’s important project of critical engineering in this sense). Only then, can Bishop speak of a moment, where the “treasured assumptions” of mainstream art are brought to bear through the criticality of the digital.

——————

* Just to make it clear, I am aware that key terms in this article such as ‘new media’ ‘digitisation’, etc carry little to no relevance anymore, (I prefer computational to be more relevant myself), and they’re only used as a replying dialogue with Claire Bishop’s essay which relies on them throughout.