Techno-fixes are big business. Taking a quick look over the Financial Times’ list of the world’s largest companies[1], it might not surprise us that five of the top spots are occupied by corporations dealing in Information Technology. The looseness of this term connotes the production and dissemination of hardware, software and data, yet increasingly such companies are moving beyond this operational remit and have begun selling a vision of how life in its totality could—and should—be lived. Over the last decade, these so-called ‘Big Tech’ companies—Apple, Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Microsoft, Amazon, and Facebook—have sought to fashion bespoke technological ‘fixes’ to particular global crises, with the aim being no less than shaping the future of humanity itself. Facebook’s Aquila solar drone project, for instance, will help four billion people in disparate regions of the globe ‘access all the opportunities of the internet’[2]. Meanwhile, Alphabet’s experimental X subsidiary is developing Project Loon, a competing network infrastructure powered by a fleet of solar balloons[3] .Which connected future do we want: one with networks of balloons or drones? Or, more to the point: one filtered through the prism of Google’s or Facebook’s algorithms? The fictional character of Gavin Belson, the deranged CEO of the quasi-Facebook-Google mashup Hooli in HBO’s comedy series Silicon Valley, captures the bizarre competitive logic of Big Tech utopianism when he states with marked frustration:

It is not only the digital divide and the contingent possibilities of market expansion which Big Tech is claiming to ‘solve’ with these ambitious infrastructural projects. Climate change, healthcare, forced migration, democracy, and automation are all staked out in branded promotional media[4] as challenges which have imminent technological solutions—just a few ‘versions’ away. In such media, we are pushed forward into a time where these complex issues have been resolved, becoming conspicuous non-features of everyday life, unrecognized background conditions that allow us to marvel at the much more spectacular and exciting business of glossy technological innovations: the familiar gesture-controlled sheets of glass, the smart-everythings and the augmented-anythings.

In these ‘design fictions’, as the Brazilian theorists Gonzatto et al. call such marketing campaigns, present crises ‘are anticipated and solved by technology’, proffering resolutions that ‘nurture consumers into consumption habits and convince investors of their capacity to fulfil those same demands’[5]. In this way, design fictions are replete with ‘solutionist’ fantasies where digital technology is positioned as a corrective to the challenges and irregularities of living. Solutionism, what Evgeny Morosov describes as an ‘intellectual pathology’[6] that can only consider problems in the form of their smart technical ‘fix’, nullifies any wider discussion of the problem at hand, abstracting the proposed resolution from the historical, social and political context of its implementation.

Therefore, whilst it is hard not to be seduced by the glossy ingenuity of projects such as Aquila and Loon, we ought to take a moment to question the frictionless future championed in these grand projects. The crises opened up and subsequently ‘solved’ by Big Tech companies scaffold the realm of present and future possibilities for our collective engagement: to determine a set of relations as constituting a crisis is to justify and arrange the ground for its resolution. For this reason, it is important to ask: Whose crisis is it anyway? Who has defined the problem that needs solving? And whose interests are being served by these proposed solutions? With such queries in mind, the benign qualities of design fictions are problematised, and their rootedness in the techno-politics of the present become plainly visible.

The recent publication of Mark Zuckerberg’s Building Global Community[7] manifesto affords such queries a timely focal point. At stake in Zuckerberg’s far-reaching manifesto is, in essence, the role that Big Tech can play in global governance. More specifically, it proposes the positive contribution that can come from Facebook’s direct engagement with the tasks of local and national security, the distribution and moderation of information, governmental politics, and fostering a post-national communalism.

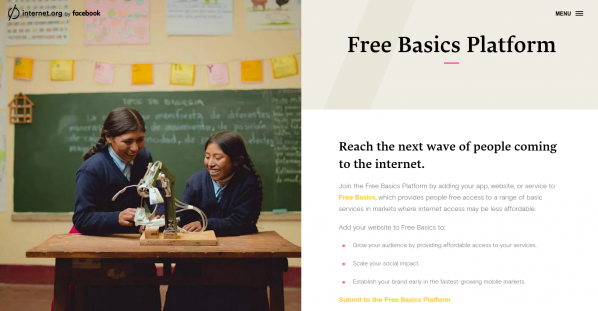

These are indeed lofty ambitions, even for a company that boasts a quarter of the world’s population as monthly active users. However, Facebook purports to relish such a challenge, motivating employees by reminding them that the “journey is 1% finished”[8]. The ‘journey’ in question here is the fixing of what Facebook sees as a crisis of disconnection experienced by those almost exclusively situated in remote regions of the Global South. Facebook asks us to imagine how much better the lives of these ‘disconnected’ people could be if only they had access to the same degree of internet connectivity that those of us in the Global North enjoy on a day-to-day basis. With these sentiments in mind, the remainder of Facebook’s arduous voyage will largely be accomplished through the development of high-profile projects such as Internet.org, where the polished graphics of constituent programmes such as Free Basics and the aforementioned Aquila act as ethical avatars for Facebook’s very own brand of solutionism.

Zuckerberg claims that, ‘in times like these, the most important thing we at Facebook can do is develop the social infrastructure to give people the power to build a global community that works for all of us’[9]. Free Basics aims to provide a free-as-in-beer (but not free-as-in-freedom) curated portal to specific sites on the internet, providing information about healthcare, news, employment, and education to individuals who might otherwise live offline and thus disconnected lives. The humanitarian rhetoric follows that bringing ‘people online’ will ‘help improve their lives’ and additionally offer these societies ‘knowledge’, ‘tools’, and global connections—these are fundamentally good things worthy of our support, right? The predictable catch is revealed in Internet.org’s promotional material, whereby companies prospecting for new markets are offered a head-start on reaching ‘the next wave of people coming to the internet’[10], albeit through Facebook’s technical infrastructure and curatorial apparatuses. Such philanthropic endeavours, if successful, assist in consolidating the corporation’s present hegemonic position in future scenarios. For governments struggling with establishing network infrastructures, Free Basics proposes an attractively simple solution that, with Facebook’s capital and clout, can be quickly deployed and established. It is however a valuable foothold, one that prescribes a developmental course that entangles the technical apparatuses of the corporation with the task of future regional governance. This is the strategic-thinking which fuels the bizarre competitive logic of Big Tech utopianism, and which sits as the political kernel of future visions. It is the rhetoric of the real-life Gavin Belsons of Silicon Valley.

By determining that there is a crisis of disconnection, Facebook prepares the ground for its resolution in the form of projects such as Internet.org. The idea that a global community of connected Facebook users can level the systematic inequalities in wages, living standards, and welfare provision inherent to globalized capitalism is a resolution that erases the multiplicity of forces acting upon a complex array of interacting crises. In making this erasure, Facebook’s logic of development draws an uncomplicated line of progression from ‘unconnected’ to ‘connected’ subjects. Such thinking is as obviously reductionist, and contestable, as the pathways that lead from ‘boy’ to ‘man’, ‘young’ to ‘old’, ‘civilised’ to ‘uncivilised’. These binary terms edifying developmental logic are laden with normative significance, implying a way of thinking about the world that presupposes and prescribes a certain way of living within it. The interconnected and complex issues that contribute to global inequality—institutional structural biases, discriminatory trade relations, the experiences of colonialism, the exploitation of resources, to name but a scant few of a vast number—do not even come into the equation. In this schematic, Facebook’s own position in relation to these matters is unacknowledged. Furthermore, the position of humans as ‘Facebook users’ worldwide is not only rendered as neutral, closing off debate around value production and labour processes in digital capitalism, but positively imbued with some sort of higher moral purpose. What does it mean, then, for Facebook to imagine a time beyond crisis? To offer a resolution to the ‘problem’ of global disconnection? As Antoinette Rouvroy would argue, such thinking inoculates the present and ‘forecloses the future’[11].

This example of Internet.org does not simply aim to expose the economic incentives lurking behind such seemingly benevolent global projects—these motives should be obvious enough already. Rather, we hope to have opened up the conversation surrounding these future visions, and the possibility of techno-fixes in general, as a means to question how we as humans come to know, relate to, and interact with both the technological era we inhabit and the perceived ‘crises’ of our time. We suggest that determining the political qualities of a ‘crisis’ opens an essentially creative and interpretative space—one that leads to a recognition of both vulnerability and empowerment. To situate yourself within the field of imagined problems and potential resolutions is to shape the possibilities of your subsequent action. Being exiled from this process, by virtue of being exterior to the kind of walled-off discussions leading Internet.org’s various initiatives, leaves us neither vulnerable nor empowered. Rather, we find ourselves neutralized in the analytical inertia of solutionist design fictions and the galleries of seductive techno-fixes rendered within.

If solutionism presupposes techno-fixes which close off alternative paths of action, Network Diagnostics intends to provide a space that expands our ability to think beyond these prescriptive future visions of Big Tech. Using ‘troubleshooting’ as a methodological tool, we propose to collaboratively examine not just what such visions include, but, perhaps more significantly, what they leave out. We aim to hold open a space for creative analytical discussion, whilst shirking the call to find a rigorous ‘fix’ to what we discover. In doing so, we hope to invigorate the modes of analysis available to those interested in the relationship between humanity and technology in the era of big data capitalism. Our collective diagnostic of the future ultimately hopes to help people understand, live within, and resist the conditioning forces we currently face in the present. Whilst we are not proposing solutions, and we do not claim to have fixed the crisis of analytical inertia wrought by the pressure of technological advancement, our practice uninhibits critique by recognizing the empowerment of claiming vulnerability, and problematising the relations at work in foreclosed, prescribed crises. Whereas Facebook and other such organisations strive to ‘move fast’, we suggest that we should dwell thoughtfully in the process of diagnosis in an effort to self-reflexively decouple the crisis from its readymade solution.

—

Niall Docherty is a PhD candidate at the Centre for Critical Theory at the University of Nottingham. His research involves an analysis of Facebook within the neoliberal context of its inception and current use, through the frames of governmentality and software studies.

Dave Young is an artist and a M3C/AHRC-funded PhD candidate at the Centre for Critical Theory at the University of Nottingham, and is currently researching bureaucratic media and systems of command and control in the US military since the Second World War.

Featured image: Screenshot of Apodemy by Katerina Athanasopoulou

Eva Kekou interviews Katerina Athanasopoulou about her film Apodemy commissioned by The Onassis Cultural Center on the theme of Emigration for Visual Dialogues 2012, and her hybrid art practice of live action, animation and film. In 2013 Athanasoppulou won the Lumen Prize, described by the Guardian as “The World’s Pre-eminent Digital Art Prize”. She works as an Animation Director, collaborates with other artists and companies, and is an Animation Lecturer at the London College of Communication.

What is your background and what brought you to London?

I studied Painting at the School of Fine Arts of Aristotle University in Thessaloniki. My work involved large canvases painted in a serendipitous way, building layers, erasing and restarting, seeing where my lines were going to take me. I was frustrated by the stillness of the final piece, longing to recreate the gesture in time that had created it. At the same time, I was passionate for cinema and animation so I tried it out in my own computer at home. In a way, I discovered animation for myself, as there was no film nor digital element in my course. That meant that there was no right and wrong way to go and it was such a joy to be producing moving images, to be able to finally paint in time! My first films were digital cutouts and manipulated live action. The big change came when I arrived in London in 2000 to do an Animation MA at the RCA, where suddenly completely new creative possibilities appeared. Short film festivals were also a source of great inspiration, places to meet like-minded filmmakers and watch films all day long.

What’s the effect of English education in your work and in the way you appreciate art?

When I became a student in the UK, I was at the same time delighted and terrified by the informality of the teacher-student relationship, like addressing your tutor by their first name. I was really impressed by the enthusiasm for research and for the creative journey itself. Process becomes a major part of the work and that frees you from concentrating only on the outcome. I saw how Animation can be enlisted in very different ways, from a more commercial manner to very left-field experimental practices so that was an exciting new point of view for me. At the same time, the early 2000s were a time of conflict between analogue and digital practices – which of course has not quite gone. As an educator myself, I love the intensity of the way that students debate their work, so the English system of education still very much inspires me.

What was your creative practice up to the Lumen Prize.

Since 2002 I have been making short experimental films that have been screened in film festivals and galleries, my process being one of playfulness and embracing chance. I like to try out different ways of creating moving images, and I try to make each film follow a different road, even though it’s very tempting – and at times fruitful – to revisit old concepts. In the last three years I have developed a big interest in Architecture and how that can be depicted in time, through 3D, 2D and live action. Animation for me is Alchemy, I combine elements together, in textured space and time and see what happens. These experiments some times involve diving into live action that I have captured on location, and other times are about creating that space digitally.

Animation Installation is a field I’m fascinated by at the moment, devising ways of materialising the digital element, of making it even more about light and shadow. My latest film, Triptych 1, was made especially for the facade of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and reimagines it as built of interconnecting corridors.

Talk to us about the theoretical and philosophical background of Apodemy.

Apodemy was commissioned by the Onassis Foundation (Stegi) on the theme of Emigration and the Economic Crisis. It was to be part of an Art Show in an old archaeological park in Athens, called Plato’s Academy Park, where the philosopher is believed to have taught. The title of the Installation was Visual Dialogues so I was drawn to Plato’s Dialogues where I discovered the metaphor of the human soul as a birdcage. I was very keen to instil in the work philosophical elements related to the space itself. With migratory birds being one of my initial ideas about the piece, the solution of a travelling birdcage in an abandoned half-finished city became apparent. The marble arms were part of Plato’s birdcage metaphor, where he describes how, as we grow up we fill our mind/birdcage with ideas/birds. When we need to recall something, we put our hand in the cage and grab a bird. I imagined those hands to be aggressive, so they became statue fragments carried by cranes that eventually mar the trolley cage’s journey. Theo Aggelopoulos inspired me with his images of a Lenin statue traversing the river and of a single arm, floating accusingly yet innocently. In times of political upheaval we like to break down our past heroes, in an attempt to cleanse ourselves of mistakes. Only that sometimes those past leaders still come back to haunt us.

What techniques did you use?

I designed the city on the computer in 3D and then started to drive cameras inside it, discovering it on the road, like I was exploring a real landscape. The film was built like a documentary, following the migration journey of a cage that is also a trolleybus, the yellow kind that I was riding in Athens when – in the late nineties – everything was promising.The construction industry ground to a halt when the crisis took hold so, today, many buildings remain unfinished and look like birdcages themselves. After the City was built, I started making the birds and the bus. Then I moved it inside the city, following a broken road which eventually leads to the fall. The entire film developed through trial and error, it was my first 3D film and I had limited time and resources. But restriction breeds creativity and, in the two months that I had to complete it, I tried to make a film designed in a minimal but impactful way.

What does the Lumen Prize mean to you and how can such a recognition make a difference in your work and life?

Winning the Lumen Prize was a great honour, especially amongst so many great works from entirely different platforms. The prize revolves around fine digital art and encompasses film, installations, interactive work, print, sculpture, collage. Amongst such a plethora of forms, it meant a lot that Apodemy was awarded, both in terms of my digital animation practice, but also as it’s a film that’s about the collapse of my country of origin. The Lumen Prize show has already been to New York and will also be part of the Digital Symposium at Chelsea College of Art and Design in March, as well as in Hong Kong in June. It’s wonderful that Lumen is propelling the film further forwards, and it’s been great to meet some of the other artists involved. Seeing the works by Nicolas Feldmyer, Kalos&Klio, Margarita Koulikourdi, Vasileios Chlorokostas and others has been very inspiring.

What draws you to animation?

Through cinema, we immerse ourselves in different waters, achieving a kind of immortality. One could argue that also happens whilst reading, or listening to music – yet somehow film combines literature and poetry and music too and almost all the senses get involved. What’s more interesting for me is the connection between moving image and the imagined: it’s almost like we dream other people’s visions and we physically try to make that disconnection from reality by favouring watching films in dark rooms. The cinema I’m interested in is one of spectacle, that transforms reality into a surreal play, that explores light and shadow and looks for monsters under the bed. At the same time, I’m currently very curious about taking animation off the screen and applying it in space, by projecting rooms, objects, corners. For me, there’s no greater magic than instilling life in the inanimate and create moving worlds that don’t depend on cameras and actors – what’s in your head can be made real, a real that’s still beautifully elusive and chimeric, that doesn’t contain all the answers but asks exciting questions.

What are your future plans?

I have been working on an experimental narrative of an obsessive mother that cocoons her children, which may work as a single screen work or perhaps as an installation that includes a film. I’m also researching the Architecture of Melancholy, which lies somewhere between cabinets of curiosities and abandoned homes. I always have several experiments on the go, it’s really about finding the right time and opportunity to commit to a project. As delightful as animation is, it takes time to complete, but it also means that ideas may have time to mature and not be rushed. As long as my ideas keep me entangled, I’m happy.

See Katerina Athanasopoulou’s work online at kineticat.co.uk

MONODROME: Art’s debt in times of crisis

AB3 Athens Biennale 2011 Monodrome

Curated by Nicolas Bourriaud and X&Y

23 October-11 December 2011

Athens Biennale 2011 was the third edition of this institution and was entitled “Monodrome”, meaning “One way street” after the 1928 text “Eisenstrasse” by Walter Benjamin. The concept of the title is obvious; after the first Athens Biennale in 2007 prophetically entitled: “Destroy Athens”, the second Biennale “Heaven” in 2009, “Monodrome” comes as a closure to this trilogy. Why Walter Benjamin? Because he was a “defeated intellectual”, according to the curators. German-Jewish philosopher, an emblematic figure of 20th century thought, gave an end to his life at the french-spanish border while trying to escape the Nazis. “He was unable to overcome his personal dead-end as a subject”, says Poka-Yio of X&Y and he continues: “The title of this exhibition after Benjamin’s text refers to a collective dead-end” currently at stake and it’s only possible fate: a cloud of doom. “Monodrome” aimed to provoke debate around “something that has fallen apart, but to also offer the possibility of a glimpse at something new to come”.

Indeed, this Biennale took place at a specific moment in Greek and global history, where all 20th century utopian narratives (i.e. modernism, ecology, metaphysics) are crashing, introducing to the whole world a humiliating and disturbing, both socially, as well as nationally, dystopian non-future. Athens, the cradle of democracy was – at the time – “rocking the world”, by suffering the experimental imposition of a non-democratic supernational regime stamped with the mark of over-privatization, a situation that immediately started spreading all over Europe. Now – that the exhibition has come to an end – nearly everyone on this planet feels that “the time” {our world – as we know it – has come to} “is out of joint”, “the very place of spectrality” (Jaques Derrida, “Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International“ Routledge, 1994: 82).

What’s art got to do with this? “Artists usually have premonitions of what’s going to happen, it is often that artists precede with their work social changes; artists are mostly intuitive, it’s at the core of their existence, this how they create” Poka-Yio says. Nicolas Bourriaud and X&Y had to deal with a situation that can be called no less than a “crisis management”. The exhibition was organized practically with no funding and was based mainly on the contribution of all participants and volunteers. The social events that were taking place during the very opening of the show were probably amongst those of the most significant importance in Greece’s postwar history. The energy and emotional vibe caused by this historical moment were the background of the Biennale and made it both a great challenge and a responsibility for the curatorial team.

Despite these critical financial and social circumstances, the Biennale was successfully realized against all odds and it can be said, that it was well received by the audience – an accomplishment on behalf of the curators who selected the works, planned and organized it. The curators of the 3rd Athens Biennale 2011 felt that “the widening situation for which Greece is a much derided yet overexposed case-study must become the focus of cultural investigation, in a way that it is no longer poignant – or even moral – to simply keep making exhibitions in the way that had become the norm in previous years”.

In order to address these issues, besides investigating the exhibition’s conceptual framework, the curators decided “to experiment with the Biennale exhibition format itself, by transforming it into an invitation to create a political moment rather than stage a political spectacle by making a call to a sit-in of collectives, political organizations and citizens involved in the transformation of society”. At another level, as the exhibition was designed and produced, its various stages of development were providing the basis for a feature film directed by Nicolas Bourriaud. Social media also played an important role in the communication strategy of this Biennale, as every event, talk, happening or performance was recorded and presented at AB3 youtube channel and one could follow it via facebook, twitter and other social platforms, as vimeo, flickr and tumblr.

The conceptual framework, upon which the theoretical thread was build, was a deep dive in the folds of Greek history. The curatorial strategy chose “to represent an ongoing crisis through historical fragments, a Benjaminian technique”. Walter Benjamin, provided with his text “Eisenstrasse” the tools for looking at history in a fragmented way, for he, according to the curators, introduced theoretical tools for looking into history with terms of “here and now”, by often making references to the city and to the popular culture of his time. “One way to talk about history is to include history”, says Nicolas Bourriaud. “The exhibition was structured as text; its narrative unfolds as one searches in the ruins and tries to read their meaning”, as one “tries to find out about new possibilities of giving meaning”.

Walter Benjamin, as a character, for the needs of this exhibition’s narrative concept was brought in a paradox dialogue with another character, a fictional one: Saint Expery’s Little Prince. This narrative plot brings this real life character, the emblematic intellectual, to meet the hero of a children’s novel, because: “a child can pose questions in an intelligent manner representing the inner child to be found in everyone” says Xenia Kalpaktsoglou of X&Y team of Athens Biennale co-founding curators. Little Prince poses all fundamental questions of “being” to the philosopher and the intellectual strives to give back the right answers. This imaginary dialogue took place in the form of sketches spreading like a graffiti-comic all over the walls of the exhibition’s main venue building. “As the intellectual retreats defeated in the face of the escalated distress, the Little Prince keeps questioning this condition with the disarming innocence and the plainspoken boldness of a child”.

The real protagonist of the exhibition, however, was Diplareios School, the main venue, a nearly disused old building located at the heart of downtown Athens in an underprivileged area, right across the City Hall and the old big open market. The local color and the smells of the market square, crowded with immigrants, ethnic shops and – especially at night – the presence of junkies, dealers and prostitutes was part of the exhibition’s “aura”. This building was literally used as a “panopticon” of both contemporary and ancient Athens and has a long history. It was built for the purposes of housing a School of Design, meant to be “the Greek Bauhaus”. Among many of its uses, it was requisitioned during the German Occupation and during the time when Athens was so badly over-built, it was hosting the offices of Urban Planning public service. The second exhibition venue was “Venizelos Museum”, a former military basis also used during the Greek dictatorship as the headquarters of torture investigating anti-regime citizens (former ΕΑΤ – ΕΣΑ).“The space is the artwork”, Bourriaud says. “Not just a venue. It’s previous functions manifest its character; it is a real protagonist”.

Diplareios School is an allegory of modern Greece surrendering itself to abandonment. Looking around all one sees is worn walls and graffiti, all one hears are the voices of protests and the ubiquitous noise of the city. The curatorial strategy for this Biennale was quite different from the two previous exhibitions, “Destroy Athens” in 2007 and “Heaven” in 2009. No big names of the international art market to be found among the artists. No self-referential patterns in this exhibition, other than “questions on the reasons behind the political crash, the crisis of moral values, the dead-end”. It was in fact a much more “introvert” exhibition, focused on the local scene, featuring mainly emergent Greek artists. The exhibited artworks in their majority came form Greece: “to include the local, to talk about local artistic production was one of our aims for this exhibition” according to Bourriaud.

Only to mention a few, Spyros Staveris, an emerging Greek photographer with a video art photo-documentation following the “Aganaktismenoi” social movement in Athens at its very birth. In the same room, “Ηommage a Athenes” a sound installation by Vlassis Kaniaris, with recorded sounds of the recent Athenian protests. One could not but mention the remarkable work of young Greek sculptror Andreas Lolis who is making cartboard boxes and felizol sculptures out of marble. “In my artwork, I try to make time stop. The reason why I am using marble, is because I want to make these fragile objects eternal”. “We all use cartboard boxes. People sleep in them. When I looked down from the windows of the Biennale venue and saw people on the terraces sleeping in cartons, it only came to me as a natural thing to co-exist with this situation – not to record it”. “This is the best time for Art. Not the art market, Art. When I recently saw the artworks of Athens Fine Art School graduates, I realized that the bubble-effect’s gone, now. These young artists, living this situation have grown into reality. There’s so much truth in their artworks”.

Another captivating artwork featured at the Biennale was “EXIT” by the Greek collective “Under Construction”, an installation of old rusty worn office desks; “in fact we present an allegorical image of Greece, using old equipment of public services, eroded now from abandonment. The hard to distinguish faded “EXIT” ‘statement’ does not exist, at least not literally”.

Rena Papaspyrou’s “Photocopies” is another stunning installation, where phone numbers printed on fragments of paper are posted on the wall. “Extending the decay of the wall, this piece secretly interacts with the graffiti notes on the wall waving alternative histories of the numerous uses of the building”. Thus the interaction between Papaspyrou’s installation and the Diplareios building creates a sense of dialogue, both in concept as well as in form.

One may wonder whether any international artists were presented in this exhibition. Lucas Lenglet, Jakob Kolding, Norman Leto, Caroline May, Josef Dabernig, Józef Robakowski only to mention a few, and of course, Julien Prévieux’s “A La Recherche du Miracle Economique”.

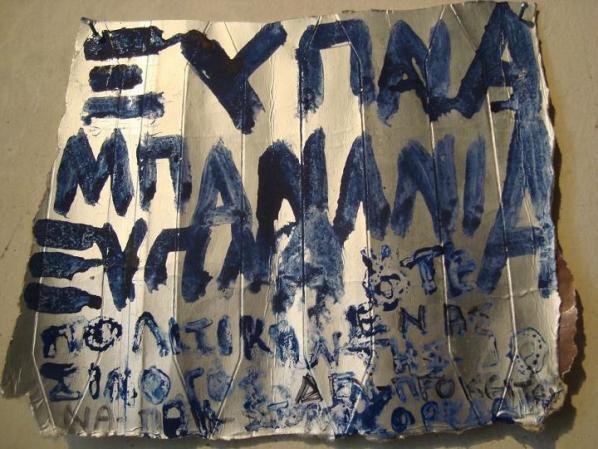

“This is a fragmented exhibition”, Bourriaud says: “one can see in this exhibition various media, film, collages, photographs, sculptures, drawings, paintings”. Amongst the artworks, the visitor would encounter several objects that have nothing to do with art but were used as tools for the exhibition narrative: a time lapse, a trip down to memory lane. For example, an object used for this purpose was a placard, that the curators found discarded after a recent protest in Athens. On the placard was written: “WAKE UP BANANA REPUBLIC”.

Also, the lost opportunity of Greek design; some of the works of students of Diplareios School were exhibited; they had been left in the old School. Posters by Greek National Tourism Organisation by Michael and Agnes Katzourakis. Pictures of Andreas Papandreou with Gaddaffi during the “good old days”. Air stewart and pilot uniforms from The Olympic Airways. In the attic of the old School, the crescendo of the exhibition’s narrative: as one faces the image of the ancient monument of the Acropolis through the dirty windows of the old School, a dead pigeon that was found there and was respectfully kept by the curators as a symbol, an omen.

The 3rd Athens Biennale 2011 was a double project; in both the form of an international exhibition and a feature film. The return of Walter Benjamin as a ghost that comes to haunt the city of Athens during this crisis period is the theme of a film directed by Nicolas Bourriaud. “It is a feature film, a film as an exhibition, a documentary based on actual characters, a docu-fiction and an experimentation with the platform of the Biennale”, says Bourriaud. “The film will be a work of fiction albeit based on real events. This is the first time that the relationship between contemporary art and filmic language is investigated in this way”. A catalogue will document the whole process of the 3rd Athens Biennale, and a DVD edition, including the movie and documents on participants’ works, will be published. Following the completion of the Biennale, the film in its final format will be distributed both in the art world and the cinema circuit. The executive producer of the movie is Kino Prod (www.kino.fr) in Paris.

Ironically, and sadly, “Monodrome“’s TV trailer was censored by the Greek National Broadcaster (ERT), who was also the major communication sponsor of the Biennale. The director of this 26’’ spot, Giorgos Zois, a talented young Greek filmmaker who has already won several international distinctions and prizes – according to his official statement as an answer to this act – attempted to “deliver the theme of the 3rd Biennale MONODROME (meaning one-way) in a series of slow-motion images of a forcibly accelerated reality depicting the one-way contemporary condition. Instinctively and suspiciously the national Greek television judged the content to be against the law that forbids “messages that contain elements of violence, or encourage dangerous behaviors, or insult human dignity”. “Apparently the daily transmission of aggressive porn-like governmental policies, does not count as an insult to viewers”. You can watch the trailer here: