This Symposium aims to bring together a range of practitioners from the Performing Arts and theorists, including those involved with, but not limited to, dance, music, opera, theatre, magic, puppetry, and the circus. To discuss issues and opportunities in designing digital tools for communication, artistic collaboration, sharing and co-creation between artists, and between artists and actively involved creative audiences.

There are numerous existing online platforms that provide immediate and easy access to a vast range of tools for creative collaboration, yet their majority create and maintain networks within a ‘noisy’ social media environment, are based on a centralised model of collaboration, and are built on corporate infrastructures with well-known issues of control, identity, and surveillance.

Focusing on the Performing Arts, the symposium will take a bottom-up approach on how to design online collaborative tools without the noise of social media, drawing on peer-to-peer decentralised practices, infrastructures for building communities of interest outside the imperatives of corporate control, developing new kinds of narratives and synergies that add depth to artistic practice, blurring the distinction between artist and audience. We will discuss about what participation, collaboration, and co-creation means for the performing artists and their audiences in an online networked world and bring to the dialogue the needs, expectations, desire, aspirations and fears of working online collaboratively. We will identify, articulate and discuss artistic, social and design issues and opportunities, analyse existing projects and current practices, experiment with ideas and concepts and visual designs.

In brief, the symposium’s goals are:

The insights of this workshop will provide the base for a second, multidiscplinary workshop that will bring together performance artists and creative technologists and coders and whch will take place on the 14th July 2015 as part of the British Human-Computer Interaction conference at Lincoln, UK.

http://designdigicommons.org/http://british-hci2015.org/participation/workshops/

“At the dawn of the new millennium, Net users are developing a much more efficient and enjoyable way of working together: cyber-communism.” Richard Barbrook.

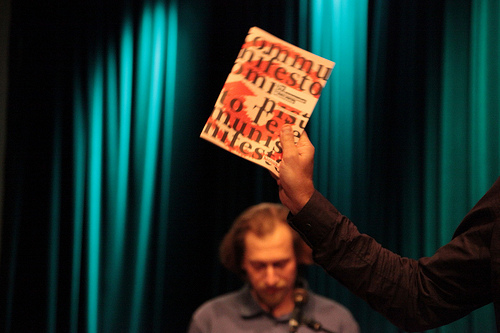

Dmytri Kleiner, author of The Telekommunist Manifesto, is a software developer who has been working on projects “that investigate the political economy of the Internet, and the ideal of workers’ self-organization of production as a form of class struggle.” Born in the USSR, Dmytri grew up in Toronto and now lives in Berlin. He is a founder of the Telekommunisten Collective, which provides Internet and telephone services, as well as undertakes artistic projects that explore the way communication technologies have social relations embedded within them, such as deadSwap (2009) and Thimbl (2010).

“Furtherfield recently received a hard copy of The Telekommunist Manifesto in the post. After reading the manifesto, it was obvious that it was pushing the debate further regarding networked, commons-based and collaborative endeavours. It is a call to action, challenging our social behaviours and how we work with property and the means of its production. Proposing alternative routes beyond the creative commons, and top-down forms of capitalism (networked and physical), with a Copyfarleft attitude and the Telekommunist’s own collective form of Venture Communism. Many digital art collectives are trying to find ways to maintain their ethical intentions in a world where so many are easily diverted by the powers that be, perhaps this conversation will offer some glimpse of how we can proceed with some sense of shared honour, in the maelstrom we call life…”

Marc Garrett: Why did you decide to create a hard copy of the Manifesto, and have it republished and distributed through the Institute of Networked Cultures, based in Amsterdam?

Dmytri Kleiner: Geert Lovink contacted me and offered to publish it, I accepted the offer. I find it quite convenient to read longer texts as physical copies.

MG: Who is the Manifesto written for?

DK: I consider my peers to be politically minded hackers and artists, especially artists whose work is engaged with technology and network cultures. Much of the themes and ideas in the Manifesto are derived from ongoing conversations in this community, and the Manifesto is a contribution to this dialogue.

MG: Since the Internet we have witnessed the rise of various networked communities who have explored individual and shared expressions. Many are linked, in opposition to the controlling mass systems put in place by corporations such as Facebook and MySpace. It is obvious that your shared venture critiques the hegemonies influencing our behaviours through the networked construct, via neoliberal appropriation, and its ever expansive surveillance strategies. In the Manifesto you say “In order to change society we must actively expand the scope of our commons, so that our independent communities of peers can be materially sustained and can resist the encroachments of capitalism.” What kind of alternatives do you see as ‘materially sustainable’?

DK: Currently none. Precisely because we only have immaterial wealth in common, and therefore the surplus value created as a result of the new platforms and relationships will always be captured by those who own scarce resources, either because they are physically scarce, or because they have been made scarce by laws such as those protecting patents and trademarks. To become sustainable, networked communities must possess a commons that includes the assets required for the material upkeep of themselves and their networks. Thus we must expand the scope of the commons to include such assets.

MG: The Manifesto re-opens the debate around the importance of class, and says “The condition of the working class in society is largely one of powerlessness and poverty; the condition of the working class on the Internet is no different.” Could you offer some examples of who this working class is using the Internet?

DK: I have a very classic notion of working class: Anyone whose livelihood depends on their continuing to work. Class is a relationship. Workers are a class who lack the independent means of production required for their own subsistence, and thus require wage, patronage or charity to survive.

MG: For personal and social reasons, I wish for the working class not to be simply presumed as marginalised or economically disadvantaged, but also engaged in situations of empowerment individually and collectively.

DK: Sure, the working class is a broad range of people. What they hold in common is a lack of significant ownership of productive assets. As a class, they are not able to accumulate surplus value. As you can see, there is little novelty in my notion of class.

MG: Engels reminded scholars of Marx after his death that, “All history must be studied afresh”[1]. Which working class individuals or groups do you see out there escaping from such classifications, in contemporary and networked culture?

DK: Individuals can always rise above their class. Many a dotCom founder have cashed-in with a multi-million-dollar “exit,” as have propertyless individuals in other fields. Broad class mobility has only gotten less likely. If you where born poor today you are less likely than ever to avoid dying poor, or avoid leaving your own children in poverty. That is the global condition.

I do not believe that class conditions can be escaped unless class is abolished. Even though it is possible to convince people that class conditions do not apply anymore by means of equivocation, and this is a common tactic of right wing political groups to degrade class consciousness. However, class conditions are a relationship. The power of classes varies over time, under differing historical conditions.

The condition of a class is the balance of its struggle against other classes. This balance is determined by its capacity for struggle. The commons is a component of our capacity, especially when it replaces assets we would otherwise have to pay Capitalist-owners for. If we can shift production from propriety productive assets to commons-based ones, we will also shift the balance of power among the classes, and thus will not escape, but rather change, our class conditions. But this shift is proportional to the economic value of the assets, thus this shift requires expanding the commons to include assets that have economic value, in other words, scarce assets that can capture rent.

MG: The Telekommunist Manifesto, proposes ‘Venture Communism’ as a new working model for peer production, saying that it “provides a structure for independent producers to share a common stock of productive assets, allowing forms of production formerly associated exclusively with the creation of immaterial value, such as free software, to be extended to the material sphere.” Apart from the obvious language of appropriation, from ‘Venture Capitalism’ to ‘Venture Communism’. How did this idea come about?

DK: The appropriation of the term is where it started.

The idea came about from the realization that everything we were doing in the free culture, free software & free networks communities was sustainable only when it served the interests of Capital, and thus didn’t have the emancipatory potential that myself and others saw in it. Capitalist financing meant that only capital could remain free, so free software was growing, but free culture was subject to a war on sharing and reuse, and free networks gave way to centralized platforms, censorship and surveillance. When I realized that this was due to the logic of profit capture, and precondition of Capital, I realized that an alternative was needed, a means of financing compatible with the emancipatory ideals that free communication held to me, a way of building communicative

infrastructure that was born and could remain free. I called this idea Venture Communism and set out to try to understand how it might work.

MG: An effective vehicle for the revolutionary workers’ struggle. There is also the proposition of a ‘Venture Commune’, as a firm. How would this work?

DK: The venture commune would work like a venture capital fund, financing commons-based ventures. The role of the commune is to allocate scarce property just like a network distributes immaterial property. It acquires funds by issuing securitized debt, like bonds, and acquires productive assets, making them available for rent to the enterprises it owns. The workers of the enterprises are themselves owners of the commune, and the collected rent is split evenly among them, this is in addition to whatever remuneration they receive for work with the enterprises.

This is just a sketch, and I don’t claim that the Venture Communist model is finished, or that even the ideas that I have about it now are final, it is an ongoing project and to the degree that it has any future, it will certainly evolve as it encounters reality, not to mention other people’s ideas and innovations.

The central point is that such a model is needed, the implementation details that I propose are… well, proposals.

MG: So, with the combination of free software, free code, Copyleft and Copyfarleft licenses, through peer production, does the collective or co-operative have ownership, like shares in a company?

DK: The model I currently support is that a commune owns many enterprises, each independent, so the commune would own 100% of the shares in each enterprise. The workers of the enterprises would themselves own the commune, so there would be shares in the commune, and each owner would have exactly one.

MG: In the Manifesto, there is a section titled ‘THE CREATIVE ANTI-COMMONS’, where the Creative Commons is discussed as an anti-commons, peddling a “capitalist logic of privatization under a deliberately misleading name.” To many, this is a controversy touching the very nature of many networked behaviours, whether they be liberal or radical minded. I am intrigued by the use of the word ‘privatization’. Many (including myself) assume it to mean a process whereby a non-profit organization is changed into a private venture, usually by governments, adding extra revenue to their own national budget through the dismantling of commonly used public services. Would you say that the Creative Commons, is acting in the same way but as an Internet based, networked corporation?

DK: As significant parts of the Manifesto is a remix of my previous texts, this phrase originally comes from the longer article “COPYRIGHT, COPYLEFT AND THE CREATIVE ANTI-COMMONS,” written by me and Joanne Richardson under the name “Ana Nimus”:

http://subsol.c3.hu/subsol_2/contributors0/nimustext.html

What we mean here is that the creative “commons” is privatized because the copyright is retained by the author, and only (in most cases) offered to the community under non-commercial terms. The original author has special rights while commons users have limited rights, specifically limited in such a way as to eliminate any possibility for them to make a living by employing this work. Thus these are not commons works, but rather private works. Only the original author has the right to employ the work commercially.

All previous conceptions of an intellectual or cultural commons, including anti-copyright and pre-copyright culture as well as the principles of free software movement where predicated on the concept of not allowing special rights for an original author, but rather insisting on the right for all to use and reuse in common. The non-commercial licenses represent a privatization of the idea of the commons and a reintroduction of the concept of a uniquely original artist with special private rights.

Further, as I consider all expressions to be extensions of previous perceptions, the “original” ideas that rights are being claimed on in this way are not original, but rather appropriated by the rights-claimed made by creative-commons licensers. More than just privatizing the concept and composition of the modern cultural commons, by asserting a unique author, the creative commons colonizes our common culture by asserting unique authorship over a growing body of works, actually expanding the scope of private culture rather than commons culture.

MG: So, this now brings us to Thimbl, a free, open source, distributed micro-blogging platform, which as you say is “similar to Twitter or identi.ca. However, Thimbl is a specialized web-based client for a User Information protocol called Finger. The Finger Protocol was orginally developed in the 1970s, and as such, is already supported by all existing server platforms.” Why create Thimbl? What kind of individuals and groups do you expect to use it, and how?

DK: First and foremost Thimbl is an artwork.

A central theme of Telekommunisten is that Capital will not fund free, distributed platforms, and instead funds centralized, privately owned platforms. Thimbl is in part a parody of supposedly innovative new technologies like twitter. By creating a twitter-like platform using Finger, Thimbl demonstrates that “status updates” where part of network culture back to the 1970s, and thus multimillion-dollar capital investment and massive central data centers are not required to enable such forms of communication, but rather are required to centrally control and profit from them.

MG: In a collaborative essay with Brian Wyrick, published on Mute Magazine ‘InfoEnclosure-2.0’, you both say “The mission of Web 2.0 is to destroy the P2P aspect of the Internet. To make you, your computer, and your Internet connection dependent on connecting to a centralised service that controls your ability to communicate. Web 2.0 is the ruin of free, peer-to-peer systems and the return of monolithic ‘online services’.”[2] Is Thimbl an example of the type of platform that will help to free-up things, in respect of domination by Web 2.0 corporations?

DK: Yes, Thimbl is not only a parody, it suggests a viable way forward, extending classic Internet platforms instead of engineering overly complex “full-stack” web applications. However, we also comment on why this road is not more commonly taken, because “The most significant challenge is not technical, it is political.” Our ability to sustain ourselves as developers requires us to serve our employers, who are more often than not funded by Capital and therefore are primarily interested in controlling user data and interaction, since delivering such control is a precondition of receiving capital in the first place.

If Thimbl is to become a viable platform, it will need to be adopted by a large community. Our small collective can only take the project so far. We are happy to advise any who are interested in how to join in. http://thimbl.tk is our own thimbl instance, it “knows” about most users I would imagine, since I personally follow all existing Thimbl users, as far as I know, thus you can see the state of the thimblsphere in the global timeline.

Even if the development of a platform like Thimbl is not terribly significant (with so much to accomplish so quickly), the value of a social platform is the of course derived from the size of it’s user base, thus organizations with more reach than Telekommunisten will need to adopt the platform and contribute to it for it to transcend being an artwork to being a platform.

Of course, as the website says “the idea of Thimbl is more important than Thimbl itself,” we would be equally happy if another free, open platform extending classic Internet protocols where to emerge, people have suggested employing smtp/nntp, xmmp or even http/WebDav instead of finger, and there are certain advantages and disadvantages to each approach. Our interest is the development of a free, open platform, however it works, and Thimbl is an artistic, technical and conceptual contribution to this undertaking.

MG: Another project is the Telekommunisten Facebook page, you have nearly 3000 fans on there. It highlights the complexity and contradictions many independents are faced with. It feels as though the Internet is now controlled by a series of main hubs; similar to a neighbourhood being dominated by massive superstores, whilst smaller independent shops and areas are pushed aside. With this in mind, how do you deal with these contradictions?

DK: I avoided using Facebook and similar for quite some time, sticking to email, usenet, and irc as I have since the 90s. When I co-authored InfoEnclosure 2.0, I was still not a user of these platforms. However it became more and more evident that not only where people adopting these platforms, but that they were developing a preference for receiving information on them, they would rather be contacted there than by way of email, for instance. Posting stuff of Facebook engaged them, while receiving email for many people has become a bother. The reasons for this are themselves interesting, and begin with the fact that millions where being spent by Capitalists to improve the usability of these platforms, while the classic Internet platforms were more or less left as they were in the 90s. Also, many people are using social media that never had been participants in the sorts of mailing lists, usenet groups, etc that I was accustomed to using to share information.

If I wanted to reach people and share information, I needed to do so on the technologies that others are using, which are not necessarily the ones I would prefer they use.

My criticism of Facebook and other sites is not they are not useful, it is rather that they are private, centralized, proprietary platforms. Also, simply abstaining from Facebook in the name of my own media purity is not something that I’m interested in, I don’t see capitalism as a consumer choice, I’m more interested in the condition of the masses, than my own consumer correctness. In the end it’s clear that criticizing platforms like Facebook today means using those platforms. Thus, I became a user and set up the Telekommunisten page. Unsurprisingly, it’s been quite successful for us, and reaches a lot more people than our other channels, such as our websites, mailing lists, etc. Hopefully it will also help us promote new decentralized channels as well, as they become viable.

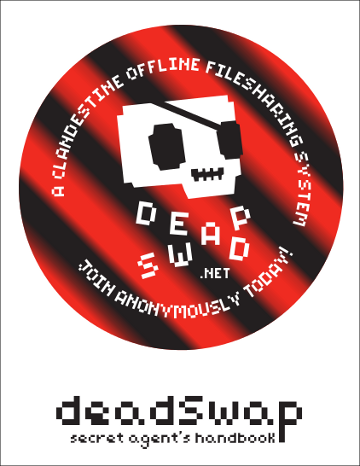

MG: So, I downloaded deadSwap (http://deadSwap.net) which I intend to explore and use. On the site it says “The Internet is dead. In order to evade the flying monkeys of capitalist control, peer communication can only abandon the Internet for the dark alleys of covert operations. Peer-to-peer is now driven offline and can only survive in clandestine cells.” Could you explain the project? And are people using it as we speak?

DK: I have no idea if people are using it, I am currently not running a network.

Like thimbl, deadSwap is an artwork. Unlike thimbl, which has the seeds of a viable platform within it, deadSwap is pure parody.

It was developed for the 2009 Sousveillance Conference, The Art of Inverse Surveillance, at Aarhus University. deadSwap is a distopian urban game where participants play secret agents sharing information on usb memory sticks by hiding them in secret locations or otherwise covertly exchanging them, communicating through an anonymizing SMS gateway. It is a parody of the “hacker elite” reaction to Internet enclosure, the promotion of the idea that new covert technologies will defeat attempts to censor the Internet, and we can simply outsmart and outmaneuver those who own and control our communications systems with clandestine technologies. This approach often rejects any class analysis out-of-hand, firmly believing in the power of us hackers to overcome state and corporate repressions. Though very simple in principal, deadSwap is actually very hard to use, as the handbook says “The success of the network depends on the competence and diligence of the participants” and “Becoming a super-spy isn’t easy.”

MG: What other services/platforms/projects does the Telekommunisten collective offer the explorative and imaginative, social hacker to join and collaborate with?

DK: We provide hosting services which are used by individuals and small organizations, especially by artists, http://trick.ca, electronic newsletter hosting (http://www.freshsent.info) and a long distance calling service (http://www.dialstation.com). We can often be found on IRC in#telnik in freenode. Thimbl will probably be a major focus for us, and anybody that wants to join the project is more than welcome, we have a community board to co-ordinate this which can be found here: http://www.thimbl.net/community.html

For those that want to follow my personal updates but don’t want don’t use any social media, most of my updates also go here: http://dmytri.info

Thank you for a fascintaing conversation Dmytri,

Thank you Marc 🙂

=============================<snip>

Top Quote: THE::CYBER.COM/MUNIST::MANIFESTO by Richard Barbrook. http://www.imaginaryfutures.net/2007/04/18/by-richard-barbrook/

The Foundation for P2P Alternatives proposes to be a meeting place for those who can broadly agree with the following propositions, which are also argued in the essay or book in progress, P2P and Human Evolution. http://blog.p2pfoundation.net

In the essay ‘Imagine there is no copyright and no cultural conglomerates too…” by Joost Smiers and Marieke van Schijndel, they say “Once a work has appeared or been played, then we should have the right to change it, in other words to respond, to remix, and not only so many years after the event that the copyright has expired. The democratic debate, including on the cutting edge of artistic forms of expression, should take place here and now and not once it has lost it relevance.”

Issue no. 4 Joost Smiers & Marieke van Schijndel, Imagine there are is no copyright and no cultural conglomorates too… Better for artists, diversity and the economy / an essay. colophon: Authors: Joost Smiers and Marieke van Schijndel, Translation from Dutch: Rosalind Buck, Design: Katja van Stiphout. Printer: ‘Print on Demand’. Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2009. ISBN: 978-90-78146-09-4.

http://networkcultures.org/wpmu/theoryondemand/titles/no04-imagine-there-are-is-no-copyright-and-no-cultural-conglomorates-too/

Michel Bauwens is one of the foremost thinkers on the peer-to-peer phenomenon. Belgian-born and currently resident in Chiang-Mai, Thailand, he is founder of the Foundation for P2P Alternatives.

It’s a commonplace now that the peer-to-peer movement opens up new ways of creating relating to others. But you’ve explored the implications of P2P in depth, in particular its social and political dimensions. If I understand right, for you the phenomenon represents a new condition of capitalism, and I’m interested in how that new condition impacts on the development of culture – in art and also architecture and urban form.

As a bit of a background, I’d like to look at what you’ve identified as the simultaneous “immanence” and “transcendence” of P2P: it’s interdependent with capital, but also opposed to it through the basic notion of the Commons. Could you elaborate on this?

With immanence, I mean that peer production is currently co-existing within capitalism and is used and beneficial to capital. Contemporary capitalism could not exist without the input of free social cooperation, and creates a surplus of value that capital can monetize and use in its accumulation processes. This is very similar to coloni, early serfdom, being used by the slave-based Roman Empire and elite, and capitalism used by feudal forces to strengthen their own system.

BUT, equally important is that peer production also has within itself elements that are anti-, non- and post-capitalist. Peer production is based on the abundance logic of digital reproduction, and what is abundant lies outside the market mechanism. It is based on free contributions that lie outside of the labour-capital relationship. It creates a commons that is outside commodification and is based on sharing practices that contradict the neoliberal and neoclassical view of human anthropology. Peer production creates use value directly, which can only be partially monetized in its periphery, contradicting the basic mechanism of capitalism, which is production for exchange value.

So, just as serfdom and capitalism before it, it is a new hyperproductive modality of value creation that has the potential of breaking through the limits of capitalism, and can be the seed form of a new civilisational order.

In fact, it is my thesis that it is precisely because it is necessary for the survival of capitalism, that this new modality will be strengthened, giving it the opportunity to move from emergence to parity level, and eventually lead to a phase transition. So, the Commons can be part of a capitalist world order, but it can also be the core of a new political economy, to which market processes are subsumed.

And how do you see this condition – the relationship to capital – coming to a head?

I have a certain idea about the timing of the potential transition. Today, we are clearly at the point of emergence, but also coinciding with a systemic crisis of capitalism and the end of a Kondratieff wave.

There are two possible scenarios in my mind. The first is that capital successfully integrates the main innovations of peer production on its own terms, and makes it the basis of a new wave of growth, say of a green capitalist wave. This would require a successful transition away from neoliberalism, the existence of a strong social movement which can push a new social contract, and an enlightened leadership which can reconfigure capitalism on this new basis. This is what I call the high road. However, given the serious ecological and resource crises, this can at the most last 2-3 decades. At this stage, we will have both a new crisis of capitalism, but also a much stronger social structure oriented around peer production, which will have reached what I call parity level, and can hence be the basis of a potential phase transition.

The other scenario is that the systemic crisis points such as peak oil, resource depletion and climate change are simply too overwhelming, and we get stagnation and regression of the global system. In this scenario, peer-to-peer becomes the method of choice of sustainable local communities and regions, and we have a very long period of transition, akin to the transition at the end of the Roman Empire until the consolidation of feudalism during the first European revolution of 975. This is what I call the low road to peer to peer, because it is much more painful and combines both progress towards p2p modalities but also an accelerating collapse of existing social logics.

That’s a less optimistic scenario… what form of conflict would this involve?

The leading conflict is no longer just between capital and labour over the social surplus, but also between the relatively autonomous peer producing communities and the capital-driven entrepreneurial coalitions that monetize the commons. This has a micro-dimension, but also a macro-dimension in the political struggles between the state, the private sector and civil society.

I see different steps of political maturation of this new sphere of peer power. First, attempts to create networks of sympathetic politicians and policy-makers; then, new types of social and political movements that take up the Commons as their central political issue, and aim for reforms that favour the autonomy of civil society; finally, a transformation of the state towards what I call a Partner State which coincides with a fundamental re-orientation of the political economy and civilization. You will notice that this pretty much coincides with the presumed phases of emergence, parity and phase transition.

Most likely, acute conflict may arise around resource depletion and the protection of these resources through commons-related mechanisms. Survival issues will dictate the fight for the protection of existing commons and the creation of new ones.

You often cite Marx, who of course also wrote at a time of conflict and social change provoked by technological and economic development. Does this tension you’re describing fit in his notion of contradictory forces conflicting – thesis, antithesis, synthesis – in other words, is this a historical materialist process?

I don’t quite use the same language, because I use Marx along with many other sources. I never use Marx exclusively or ideologically, but as part of a panoply of thinkers that can enlighten our understanding. My method is not dialectical but integrative, i.e. I strive to integrate both individual-collective aspects and objective-subjective aspects, and to avoid any reductionist and deterministic interpretations. Though I grant much importance to technological affordances, I do not adhere to technological determinism, and I don’t find that I pay much attention to historical materialism, since I see a feedback loop between culture, human intentionality, and the material basis. Technology has to be imagined before it can be invented.

My optimism is grounded in the hyperproductivity of the new modes of value creation, and on the hope that social movements will emerge to defend and expand them. If that fails to happen, then the current unsustainable infinite growth system will wreak great havoc on the biosphere and humanity.

As you say classical or Marxist economics don’t really suffice to describe the current situation. Is one aspect of this problem that the classical distinction between use and exchange doesn’t fit with a situation in which many of the “uses” are ludic, and have an exchange system built into them? I’m thinking of on-line gaming specifically. But it has always been difficult to place art in this simple use/exchange polarity. Do you see any revisions to that polarity today?

I’m not sure the ludic aspect is crucial, as use value is agnostic to the specific kind of use, just as peer production is agnostic as to the motivation of the contributors. However, our exponential ability to create use value without intervention of the commodity form, with only a linear expansion of the monetization of peer platforms, does create a double crisis of value. On the one hand, capital is valuing the surplus of social value through financial mechanisms, and is not restituting that value to labour, just as proprietary platforms do not pay their value producers; on the other hand, peer producers are producing more and more that can’t be monetized. So we have financial crisis on the one hand, a crisis of accumulation and a crisis of precarity on the other side. This means that the current form of financial capitalism, because of the broken feedback loop between value creation and realization, is no longer an appropriate format.

Regarding your ‘integrative method’, this is a much more sophisticated take on economics that places it in relationship to other, cultural, dimensions of human life. And the imagination is central to it. Given that, do you see any special role for art in this transition?

Art is a precursor of the new form of capitalism, which you could say is based on the generalization of the ‘art form of production’. Artists have always been precarious, and have largely fallen outside of commodification, relying on other forms of funding, but peer production is a very similar form of creation that is now escaping art and becoming the general modality of value creation.

My take is that commodified art has become too narcissistic and self-referential and divorced from social life. I see a new form of participatory art emerging, in which artists engage with communities and their concerns, and explore issues with their added aesthetic concerns. Artists are ideal trans-disciplinary practitioners, who are, just as peer producers, largely concerned with their ‘object’, rather than predisposed to disciplinary limits. As more and more of us have to become ‘generally creative’, artists also have a crucial role as possible mentors in this process. I was recently invited to attend the Article Biennale in Stavanger, Norway, as well as the artist-led herbologies-foraging network in Finland and the Baltics, and this participatory emergence was very much in evidence, it was heartening to see.

We might see as opposed to that sort of grassroots participatory engagement, the entities you refer to as the “netarchies.” Their power lies in the ownership of the platform they exploit for harvesting user-originating information and activities. How hegemonic is this ownership? At what point does it become impossible to create a “counter-Google”?

The hegemony is relative, and is stronger in the sharing economy, where individuals do not connect through collectives and have weak links to each other. The hegemony is much weaker in the true commons-oriented modalities of production, where communities have access to their own collaborative platforms and for-benefit associations maintaining them.

The key terrain of conflict is around the relative autonomy of the community and commons vis a vis for-profit companies. I am in favour of a preferential choice towards entrepreneurial formats which integrate the value system of the commons, rather than profit-maximisation. I’m very inspired by what David de Ugarte calls phyles, i.e. the creation of businesses by the community, in order to make the commons and their attachment to it viable and sustainable over the long run. So, I hope to see a move from the current flock of community-oriented businesses, towards business-enhanced communities. We need corporate entities that are sustainable from the inside out, not just by external regulation from the state, but from their own internal statutes and linkages to commons-oriented value systems.

Counter-googles are always possible, as platforms are always co-dependent on the user communities. If they violate the social contract in a too extreme way, users can either choose different platforms, or find a commons-oriented group that develops an independent alternative, which in turn maintains the pressure on the corporate platforms. I expect Google to be smart enough to avoid this scenario though.

As you’ve said elsewhere, many of these issues are about a new form of governance. Do you see any of this as particularly urban in character — I mean, about organization at the smaller scale, regionally focused, as opposed to at the level of the nation state. Does propinquity matter at all to this — the importance of living together? This seems to relate to a — not a contradiction or tension exactly, but a complication of the P2P notion — that relationships are dispersed, yet a number of the parallels you draw with historical models (for example the Commons) connect with social situations in which people lived very close together. A fairly strong notion in urbanistic thinking is that propinquity is a good thing. In the past that was part of many artistic relationships also: cities as milieux of artistic production/creativity, artists’ colonies; working cheek by jowl with other creative people and breathing the same air. Is this notion in any sense undermined by dispersed networks?

I think we are seeing the endgame of neoliberal material globalization based on cheap energy, and hence a necessary relocalization of production, but at the same time, we have new possibilities for online affinity-based socialization which is coupled with resulting physical interactions and community building. We have a number of trends which weaken the older forms of socialization. The imagined community of the nation-state is weakening both because of the globalized market; the new possibilities for relocalization that the internet offers, which includes a new lease of life to mostly reactionary and more primary ethnic, regional and religious identities; but also because of this important third factor, i.e. socialization through transnational affinity based networks.

What I see are more local value-creation communities, but who are globally linked. And out of that, may come new forms of business organization, which are substantially more community-oriented. I see no contradiction between global open design collaboration, and local production, both will occur simultaneously, so the relocalized reterritorialisation will be accompanied by global tribes organized in ‘phyles.’ I think the various commons based on shared knowledge, code and design, will be part of these new global knowledge networks, but closely linked to relocalized implementations.

One interesting question is what forms of urbanism come out of p2p thinking. The movement is in the process of thinking this through, in fact a definition of p2p urbanism was just published by the “Peer-to-peer Urbanism Task Force” (http://p2pfoundation.net/Peer-to-Peer_Urbanism).

This promotes, in general terms, bottom-up rather than centrally planned cities; small-scale development that involves local inhabitants and crafts; and a merging of technology with practical experience. All resonant in various ways with p2p approaches. But this statement also provokes a few questions: It calls for an urbanism based on science and function; in fact it explicitly promotes a biological paradigm for design. At the risk of over-categorizing, isn’t this a modernist understanding of design — or if not, how is it different? This document also refers to specific schools of urban design: Christopher Alexander, and also New Urbanism. On the side of socio-economics though, New Urbanism has been criticized (for example in David Harvey’s Spaces of Hope); some see it as nostalgic and in the end directed at a narrow segment of the population. Christopher Alexander’s work on urban form has also been criticized as, being based on consensus, restrictive in its own ways. In fact, might not p2p principals call for creation of spaces that allow dissent and even shearing-off from the mainstream? Might there be a contradiction built into trying to accommodate the desires for consensus and for freedom? Contradiction can be a source of vitality, certainly in art; but it can raise some tensions when you get to built form and a shared public realm.

I cannot speak for the bio- or p2p urbanism movement, which is itself a pluralistic movement, but here’s what I know about this ‘friendly’ movement. I would call p2p urbanism not a modernist but a transmodernist movement. It is a critique of both modernist and postmodern approaches in architecture and urbanism; takes critical stock of the relative successes and failings of the New Urbanist school; and then takes a trans-historical approach, i.e. it critically re-integrates the premodern, which it no longer blankly rejects as modernists would do. I don’t think that makes it a nostalgic movement, but rather it simply recognizes that thousands of years of human culture do have something to teach us, and that even as we ‘progressed’, we also lost valuable knowledge. Finally, I think there is a natural affinity between the prematerial and post-material forms of civilization. The accusation of elitism is I think also unwarranted, given what I know of the work of bio-urbanists amongst slumdwelling communities. However, I take your critique of consensus very seriously, without knowing how they answer that. You are right, that is a big danger to guard for, and one needs to strive for a correct balance between agreed-upon frameworks, that are community and consensus-driven, and the need for individual creativity and dissent. Nevertheless, compared to the modernist prescriptions of functional urbanism, I don’t think that danger should be exaggerated.

Following on this track, I’d like to pose another question that relates to living together. The P2P concept depends on the difficulty of controlling the activity of peers on a network: i.e. it’s impossible to lock down the internet. Doesn’t this degree of freedom also eliminate those social controls that might be considered “healthy” – for example, controls over criminal activity. David Harvey (to bring him in again), in his paper “Social Justice, Postmodernism and the City”, lists social controls among several elements of postmodern social justice. When the grand narratives have been replaced by small narratives, there remains a need to limit some freedoms. How does p2p thinking deal with this?

I think we can summarize the evolution of social control in three great historical movements. In premodern times, people lived mostly in holistic local communities, where everyone could see one another, and social control was very strong. At the same time, vis a vis more far-away institutions, such as for example the monarchy, or the feudal lord, or say in more impersonal communities such as large cities, compliance was often a function of fear of punishment. With modernity, we have a loss of the social control through the local community, but a heightened sense of self through guilt, combined with the fine-grained social control obtained through mass institutions, described for example by Michel Foucault. The civility obtained through the socialization of the imagined community that was the nation state, and the educational and media at its disposal, also contributed to social control and training for civil behaviour.

My feeling about peer-to-peer networks is that they bring a new form of very real socialization through value affinity, and hence, a new form of denser social control in those specific online communities which also usually have face-to-face socialities associated with them. But this depends on whether the community has a real value affinity and a common project, in which case I think social control is ‘high’, because of the contributory meritocracy that determines social standing. On the contrary, in the looser form of sharing communities, say YouTube comments for example, we get the type of social behaviour that comes from anonymity and not really being seen.

So the key challenge is to create real communities and real socialization. Peer to peer infrastructures are often holoptical, i.e. there is a rather complete record of behaviour and contributions over time, and hence, a record of one’s personality and behaviour. This gives a bonus to ‘good ethical behaviour’ and attaches a higher price to ‘evil’. On the other hand, in the looser communities, subject to more indiscriminate swarming dynamics, negative social behaviour is more likely to occur.

A key difference between contemporary commons and those of the past is that the new ones are immaterial and global. The model for P2P exchange seems to be of autonomous agents relating and forming new communities not based on membership in an originary cultural group. Given a global distribution, how do local, cultural factors play into the model of globalized distributed networks? How does P2P accommodate cultural specificity, especially specificity with deep historical roots; and how does that accommodate the development of new culture, art?

In my view, the digital commons reconfigure both the local and the global. I think we can see at least three levels, i.e. a local level, where local commons are created to sustain local communities, see for example the flowering of neighbourhood sharing systems; then there are global discourse communities, but they are constrained by language; so rather than national divisions, which still exist but erode somewhat as a limitation for discourse exchange, there is a new para-global level around shared language. At each level though, cultural difference has to be negotiated and taking into account. If there is no specific effort at diversity and inclusion, then affinity-based communities reproduce existing hierarchies. For example, the free software world is still dominated by white males. Without specific efforts to make a dominant culture, which has exclusionary effects, adaptive to inclusion, deeper participation is effectively discouraged. Of course, as the dominant culture may not be sufficiently sensitive, it is still incumbent on minoritarian cultures to make their voice and annoyances heard. Obviously, each culture will have to go through an effort to make their culture ‘available’ through the networks, but I think the specific role of artists, now operating more collectively and collaboratively than before, is to experiment with new aesthetic languages, so that non-conceptual truths can be communicated.

The innovation I see as most important though is in terms of the globa-local, i.e. a relocalization of production, but within the context of global open design and knowledge communities, probably based on language. I also see a distinct possibility for a new form of global organization, i.e. the phyle I mentioned earlier, as fictionalized in Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age and operationalized by lasindias.net. These are transnational value communities that created enterprises to sustain their livelihoods.

I see the key challenge, not just to develop ‘relationality’ between individuals, as social networks are doing very well, but to develop new types of community, such as the phyle, which are not just loose networks, but answer the key question of sustainability and solidarity.

In terms of culture, what I see developing is a new transnational culture, based on value and discourse communities, based on language, that are neither local, nor national, nor fully cosmopolitan, but ‘trans-national’.

And the creative relationships between artists can in some sense be a model for this?

Artists have been precarious in almost all periods of history, and their social condition reflects what is now very common for ‘free culture’ producers today, so studying sustainability and livelihood practices of artist communities seems to me to be a very interesting lead in terms of linking with previous historical experience. I understand that artists now have increasingly collaborative practices and forms of awareness. Unfortunately, my own knowledge of this is quite limited so this is really also an open appeal for qualified researchers to link art historical forms of livelihood, with current peer production. In some ways, we are all now becoming precarious artists under neoliberal cognitive capitalism!

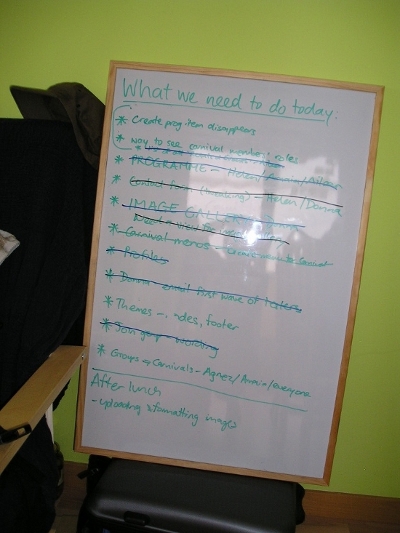

Helen Varley Jamieson’s account of working collaboratively in Madrid at the Eclectic Tech Carnival. On a ‘sprint’, with five women coming together for a week to rebuild the group’s website, physically & remotely.

In the last week of June I went to Madrid for the Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC) website workweek – the collective effort of five women coming together for a week to rebuild the group’s website. This is sprint methodology, a concept that I first met in Agile software development, but one that is being increasingly applied as a successful creative collaboration methodology. During the workweek I blogged about the process and this article is an assemblage of the blog posts.

Thinking about the concept of the sprint, I realised that over the years, I’ve participated in a number of theatrical “sprints” although we didn’t call them that. In fact it could be argued that the normal development process for theatre productions in New Zealand is the sprint – a three or four week turnaround of devising/rehearsing/presenting. Except that it doesn’t usually continue the Agile process after the first sprint – evaluation, refinement then the next sprint and iteration – and as a result, the work is often undercooked. But theatre projects that better fit the sprint analogy are some of the workshop-performance processes that I’ve participated in at theatre festivals, where a small group comes together for a few days to create a performance, then some time later meets again in another situation, perhaps a slightly different configuration of people, for another sprint. Each sprint generates a stand-alone performance or work-in-process showing, as well as contributes to a larger evolving body of work that forms the whole collaborative project. Two such projects that I’ve been part of are Water[war]s and Women With Big Eyes (with the Magdalena Project).

Recently I participated remotely in a Floss Manuals sprint, developing a manual for CiviCRM (which is something that I use with the Magdalena Aoteroa site). In this sprint, a group of about 15 people met somewhere in the USA to create a manual for CiviCRM. A few more of us were online, doing things like copy-editing the content. Most of the time there were people active in the IRC channel, chatting about the project and other things going on around them, so I got a sense of their environment, time zone and the camaraderie generated by the intense process.

Sprinting seems like a very logical and effective way to work in many situations: in software development, where each sprint focuses on specific feature development, and allows for a lot of flexibility and adaptation as the project progresses; in theatre, where limited resources make it a practical way to work, and the time pressure forces us to be resourceful and imaginative and also with networks, such as the Eclectic Tech Carnival, whose organisers don’t get to meet physically very often. It also makes sense in the context of our hectic lives, to block out a week or a few days when we agree to put everything else on hold and commit to intense, focused work instead of trying to juggle and multitask, with deadlines pushing out and out.

By halfway through the second day of the workweek, the wiki we used to plan and manage the project was filling up with tech specs, user requirements, design ideas, etc. We were getting encouraging emails from others in the network, and chatting to each other across the table and in the IRC. After lunch we did the new Drupal install and things seemed to be moving forward quickly in an organised and collaborative way.

Wednesday afternoon and the heat was oppressive; I put a little rack under my laptop because she was so hot, and my hands were too sweaty to use the trackpad. It wasn’t just Madrid’s weather that was making me sweat – we’d all been working hard on the new site since our late start in the morning (following on from a late night …). Agnes was busy developing the theme for the site, Aileen was working on profiles and user roles while Donna and Amaia were trying to configure mailing list integration and I was using the command line to drush download modules – much easier and quicker than the process of downloading, unpacking, ftp-ing and installing! And very exciting for me to use the command line, which I generally only get to do when hanging out with the /ETC crowd.

We were in that murky middle phase of the process: we’d done a lot of groundwork in terms of defining users, content types, general structure and the functionality required, but everything was still very bitsy and amorphous. But the installation of the test site had happened very easily yesterday, using drush, so that meant we now had something tangible to work with.

Working with Drupal can be pretty frustrating; it seems that every step of the way, another module is required to do what we want – then that module requires other modules, and then every little thing has to be finely configured to work just right with every other piece of the puzzle. From my previous experience with the Magdalena Aotearoa site, I knew we are doing a lot better this time in terms of defining what we need first, but some things we just can’t define until we know what’s possible, which we don’t really know for sure until we actually try it. We *think* we’re going to be able to do everything we want, but getting there isn’t simple. Also, the naming of different components and modules is sometimes ambiguous or confusing – the documentation ranges from really clear and detailed to non-existent. And some things just didn’t seem intuitive to me.

But, with five brains and our different complementary experiences and skills, I was still confident that we would have a new site by the end of Friday; maybe not a completely finished one, but a web site is never finished, is it?

On Friday morning the heat broke with a thunder storm and cooling welcome rain, but it didn’t last long. For some reason I woke up at 7.30am, ridiculously early as we hadn’t gone to bed until 2am. But I was wide awake so I enjoyed a couple of hours of quiet before everyone else awoke, drinking coffee and answering emails. The day before, Agnez and I had got up early to do yoga on the terrace, but the intense rain prevented that on Friday.

The test site was up and some of the others not present in Madrid were looking at it and trying things out. We’d solved a lot of problems but there were still a number of things not working. I had learned heaps about Drupal in the previous four days, particularly about organic groups, roles, permissions, and views. Altogether it is potentially incredibly flexible and powerful, however it takes time to work out how things need to be done and sometimes it is a confusing and circular process. Changing a setting in one place can stop something in a completely different place from working. However the combination of skills and experience between the five of us meant that usually one of us had at least an idea about how to do things and a couple of times we drew on external expertise via IRC or email.

On the last day, Agnez worked on finishing the theme while Aileen and I tried to work out why our groups are no longer displaying in the og_my view, and how to make the roles of group members visible. Donna had found that mailhandler and listhandler didn’t seem to be a practical way to integrate our mailman lists with Drupal after all – for the time being we’ll stick to the old system – and Amaia had been working on a way to create a programme for each event. The idea is that each /ETC event can be created as an organic group with the organisers having control over content and members within that group, but not being able to edit the rest of the site content. By Friday, we had this working pretty much how we wanted it.

We had planned a barbecue to celebrate the end of the workweek, but the rain prevented that. Instead, we ate inside then took turns to suffer humiliation and defeat with Wii Fitness (Amaia had clearly been practising!). In fact it wasn’t really the end of the sprint – rain again on Saturday morning meant that we decided to keep working longer and only went into the city in the afternoon, for a wander around and then the Gay Pride parade. On Sunday as we began to scatter back to our different parts of the globe, the site was still not live, as we were waiting for more feedback from testers and the finishing of the design themes. However, the site is essentially functional and should be live very soon.

The sprint process enabled us to achieve a considerable amount in a short space of time, sharing our knowledge and developing our skills. We also had great conversations over meals, explored Madrid and Colmenar Viejo, learned how to make Spanish tortilla, attempted a bit of Spanish, went swimming and did yoga. I even fitted in a performance on the first night, with Agnez, and dinner with friends another night. It’s amazing what you can do when you put the rest of your life on hold for a week; the only downside is the catching up afterwards.

Featured image: make art is an international festival focusing on Free/Libre/Open Source Software (FLOSS), and open content in digital arts

make art, one of the world’s most important free and libre art events, happens far away from the European metropolis, in the small town of Poitiers. However, it does not represent an integral piece of the ville‘s agenda to favour cultural tourism and development, as we might suppose thinking of some Brazilian film festivals and even of Bilbao’s Guggenheim. If something is to blame, it should be the grassroots effort of the native GOTO10 collective.

The name might sound familiar because not long ago they were doing a series of workshops in the UK to introduce FLOSS tools using their own pure:dyne operational system – a GNU/Linux distribution for multimedia creation. Having received some funding from the Arts Council, pure:dyne recently grew in efficiency and popularity.

Personally, the first time I heard about GOTO10 was in 2006, at that year’s Piksel festival. Some of the group’s members were there for audiovisual performances. Yes, they are artists as well – in fact, on the same days of make art, the group was taking part in the Craftivism exhibition, in Bristol. And between producing events, engineering software and, well, making art, they also found time to publish a book.

As diverse as these projects might be, they can all be inferred from the GOTO10’s creative practice, in respect of their real time interaction with people (in workshops) and machines (in live coding, etc). Given the way make art, pure:dyne and the group’s performances are interconnected, we could see them as one and the same activity, extending itself to various platforms.

I wouldn’t go as far as to say that, similarly, GOTO10 is a poitou group that has been expanded to other parts of the world. But, now that it has members from Greece, the Netherlands, Taiwan and the UK, the localization of make art seems even more meaningful to the collective’s identity, hinting on where and why it started.

According to Thomas Vriet, one original member who is still in town and mainly responsible for make art production. The group first got together in 2003 to promote digital art performances, workshops and exhibitions in Poitiers – sharing thoughts and ideas on things they were interested in, but could not find in the local art scene or École de Beaux-Arts.

So, in the same way pure:dyne was developed to cope up with GOTO10’s own needs for a live operational system capable of realtime audiovisual processing, make art is the ideal festival they’d wish to attend in town. Both projects find their reason in the group’s artistic demands, and grew simultaneously from it: the inaugural version of the distro was released in 2005, right on time to be used in a workshop in the first make art the following year.

Even though make art’s production is concentrated locally, the event is curated online, by the whole of GOTO10. The other member directly implied in this year’s planning, Marloes de Valk, arrived from Amsterdam just in the first day of the festival. make art is a group initiative that cannot be isolated from the larger open source community – a circuit that includes not only artists and programmers, but other venues as well. It is from this sizeable repository that the pieces that constitute the event’s programme come from. The aforementioned Piksel, for instance, has previously contributed to make art with a special selection of Norwegian works, creating an unexpected interchange between Bergen and Poitiers.

Together with the different Pixelache editions, these festivals form an international calendar of FLOSS art events, closely committed to developments in technology and aesthetics that, in many senses, are far more interesting that the new media proofs-of-concept proliferating elsewhere. But how does such package of extraordinary themes work in the traditional platform of the French countryside?

Altogether, make art seems to be the right size for Poitiers – not too small to feel incomplete, neither too big to feel overwhelming. The night programme may put you off if you are on a budget and decided to stay in the youth hostel (like me): there are no buses to that area after 8pm, forcing you to endure a half hour walk through cold streets. Apart from that, the city space is very well occupied by the festival, with the exhibition and debates in the central Maison de l’Architecture and a couple performances in other venues, emphasizing the curatorial logic. Posters are everywhere in town, competing for attention with those from the film festival.

However, the participation of the poitou community seems very restricted. So far, no local project has ever been sent in response to make art’s call. It might be that the theme is still alien to most people. Not surprisingly, the activity that attracted the majority of local public was the debate “Internet, Freedom and Creation” – which, beyond dealing with themes of more general concern (digital freedoms and copyright), was in French.

One of the efforts to increase this involvement was to open free places in the Fork a House! workshop to local students. Student volunteers could also be found mediating the exhibition and assisting production.

In that sense, the project that seemed to make the most of the festival’s situation was the frugal Breakfast Club. The first of these morning talks hosted by Nathalie Magnan was especially refreshing after the highly technical presentations the day before. Complex subjects were re-discussed over croissants, bringing the tone and rhythm of the event closer to the atmosphere of the #makeart IRC channel (which sometimes was livelier than the physical space).

The priority of Breakfast Club was not transparent accessibility but dialogue. Less of a tutorial and more like the public forum an open-source project cannot really do without. It made things more understandable to a laymen’s audience; it made the whole festival experience more coherent, pointing to directions in which it should grow within the city’s everyday life and structure – without having to be included in Poitiers’ tourism department masterplans.