Features Image: “Dead Copyright” installation view, 2015

Antonio Roberts is a digital artist based in Birmingham. In 2011 he has completed his Masters level studies in Digital Arts in Performance at Birmingham City University. His artwork focuses on the errors and glitches generated by digital technology. An underlying theme of his work is open source software and collaborative practices. His video work has been screened in Chicago, Illinois, at GLI.TC/H, Notacon in Cleaveland, Ohio, and Newcastle Borough Museum and Art Gallery, amongst other places.

In October 2015 he opened his first solo exhibition, “Permission Taken“, at Birmingham Open Media and in these weeks is taking part to “Jerwood Encounters: Common Property” (15th January – 21st February 2016, Jerwood Visual Arts), a group show curated by Hannah Pierce focused on the limits of Copyright when it’s about visual arts, with two projects: the installation “Transformative Use” and a collection of four works, “I Disappear”, “Blurred Lines”, “My Sweet Lord” and “Ice Ice Baby”.

Filippo Lorenzin: You’ve been always interested in how corporate and industrial logics affect daily life and art. How did you get interested in these questions?

Antonio Roberts: It’s a by-product of my interest in open source software and free culture, something which I’ve been interested in from as early as 2002 but only started taking seriously around 2007. One of the main motivators of this was my reaction to Adobe Photoshop and its influence on creative practices. My experience of studying Multimedia Graphics – and I’m sure the same can be said for Graphic Design, Illustration and any creative practice – was that it seemed more like an exercise in how to use Adobe products, not how to be creative with tools. It felt like Adobe software had gone from being one of the many tools for creating art to the art in itself. This corporate sponsorship of course has many implications for how we create and disseminate art. It poses restrictions and dictates who and who cannot create art.

FL: Copyright issues are one of the main focuses of your research and this fascinates me because of your age. You (as me, by the way) have experienced probably the most troublesome period for Copyright systems, with the wide spread of p2p networking and remixing approaches to cultural industry products. What do you think?

AR: I’m inclined to agree. I’ve had access to the internet since I was around 14 years old and in that time I’ve seen the internet and culture as a whole change drastically. For me the rise and fall of Napster, spearheaded by Metallica’s very public outcry against it, signalled the beginning of the end of the free internet that I had only known for not even a year.

Around that time Digital Rights Management (DRM) became a hot topic. The entertainment industry saw it (and suing everyone) as the only way to protect their property and so kept bundling DRM with their products, which often at times resulted in a broken experience for the user. One example that springs to mind was the attempt to make CDs unreadable by computers (and so prevent ripping), by adding in corrupted data at the beginning of CD. Whilst it did temporarily stop people to using it on computers – you could simply use a marker pen to circumvent it – it also prevented some CD players from using the CD and in general was obtrusive. This cat and mouse game is still going on to the point where simply attempting to bypass DRM to watch/listen to something that you have purchased, can be an illegal act.

As mentioned before, It wasn’t until around 2007 that I began to reconsider how Copyright affected my work. By this time I saw that there was more weight being pushed behind open source software, free culture and things like the Creative Commons licences, and so I started to get involved myself. The first stage was ditching all proprietary software (which I did in 2009) and then licensing my work under Creative Commons licences.

FL: “Jerwood Encounters: Common Property”, curated by Hannah Pierce, is a group show that seeks to investigate the new borders of Copyright, especially in regard of art. How would you define the state of these questions in UK?

AR: I think Copyright as a whole is in a terrible state. As Cory Doctorow suggests in the exhibition programme (which is in itself an excerpt from his book “Information Doesn’t want to be Free”) Copyright as we know it isn’t written for artists or any individual. Its verbose terms and complexities cannot be understood and are probably not even read by most of us. They are written for other lawyers. If, in order to go about our creative business, we are expected to read and understand the terms and conditions and law – it is estimated that it would take 76 days to read all of the Ts and Cs of websites we use – what time do we have to be creative?

FL: What’s your point of view, from your position as an artist?

AR: I think Copyright is a mess because it tries to dictate how we should be creative. Creativity is free-flowing. Copyright, and its cousins patents and trademarks, justify their existence by saying that these restrictions encourage innovative new ideas but what they do is just stop us.

FL: “Dead Copyright” reminds me some reflections by Walter Benjamin on the shock of the city, about how advertising assaults our senses 24/7 with louder and louder messages – until it reaches a state of entropy. At this stage the message isn’t actually more important than the media itself, quoting Marshall McLuhan, and all the brands create a single, colourful ambient. How much this reality has been voluntarily planned by corporations, in your own opinion?

AR: I think it’s all completely planned. The more pervasive the advertising becomes the more we accept it as part of our every day life and culture. On the other side this does mean that they have to try ever more invasive methods to get our attention. Think about the uproar over the Coca Cola van at Christmas, or Cadbury’s at Easter. They have usurped the original holidays and are more important.

FL: The reduction of brands to colorful simple shapes created something that visually reminds some of op art works, a movement that experimented with visual perceptions and that has been an important inspiration for fashion and design. I was just wondering what you think of this similarity: is there any real connection between your work and those works?

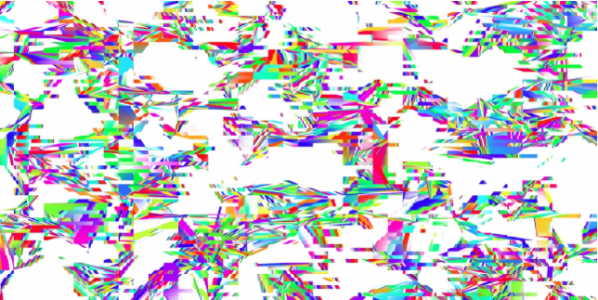

AR: Yes, certainly and this comes through with my use of glitch art techniques. In glitch art we’re often trying to find signal in the noise, and I find that many successful glitch art works (however you define successful) have some resemblance to the original yet are transformed and destroyed in way.

FL: With “Transformative Use” you use shapes that recall not just brands, but a wider imagery. It’s as if you’re focusing on other targets: can I ask you how did you get interested in this new research?

AR: I recalled all that I had learnt during my residency at University of Birmingham and during the CopyrightX course. From this I paid particular focus to the Sonny Bono act from 1998. This effectively extended the Copyright terms so that it won’t be until 2023 until works from 1923 begin to enter the Public Domain. This act is sometimes called the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, which led me to use them as a focus point for the work. Mickey Mouse should, by now, be in the Public Domain but they’ve fought to stop this in order to “protect” their brand.

People in favour of long or perpetual Copyright terms usually point to it allowing artists to reap the benefits of creating work. In truth, however, only a very small percentage of works made will be profitable in the future. To put it another way, how many books published today will see reprints? I don’t have any official statistics, but I know it would be a small percentage. So, extended Copyright terms only really benefit the small percentage of artists or publishers, whilst harming everyone else.

FL: What does it mean to deal with corporate imagery within such a chaotic and in a somewhat charming ambience? I mean, what remains a logo or a character when it gets lost within this borderless blob? Are the corporations losing their borders too, maybe?

AR: Yes.

FL: As discussed before, “Transformative Use” has been inspired by two previous projects: do you think that in future you’ll make a work that will update for the fourth time these reflections of yours?

AR: Most certainly yes. “Permission Taken” will be having an iteration at the University of Birmingham in March 2016 and will feature new and existing work. Aside from this I will continue to work with found materials but with a more explicit intention to provoke discussion around Copyright.

Copyright has been a relevant topic since the development of the printing press. It grants the author the exclusive right to reproduce, publish, and sell the content and form of intellectual property. The copy & paste mentality of the Internet user brought chaos to the system. Blockchain technology should now manage the author and marketing rights in a way that is more transparent, completely free of Bitcoin and monetary background. The idea had its origin in the art scene.

The Internet is a space without horizons or frontiers. It has changed our environment and also, thereby, our sensory perception. In ‘the real world’ we are confronted everywhere by people gazing deeply into smartphones: on the street, on the subway, in airplanes, in queues and cafés. Interpersonal dialogue is increasingly being conducted in the virtual sphere. How does the art scene react to new technological developments in arts? I asked Alain Servais (collector), Wolf Lieser (gallerist) and Aram Bartholl (artist.)

AD: Alain, you are collector of digital art since many years. How actively do you use the Internet and the possibilities that it brings for research into art?

AS: I have the opportunity to generally be able to experience art in the real. This is still an indispensable element in the process of acquiring. I’m a big user of the Internet when it’s a question of looking for information on art that’s of interest to me. The key information I always try to gather before acquiring a work is: – a document collating the works which have marked the evolution of the artist’s practice –a piece of writing by an academic, curator or critic contextualizing the artist’s work – an interview with the artist, as I want to hear his/her ‘ voice’ speaking about on his/her art – and a biography.

AD: Wolf, how much do you use the Internet and its possibilities for better marketing in the art scene?WL: We have a presence on various social media and websites, for example, FB, FLICKR, Bpigs, ArtfactsNet, etc. But we try to limit it to those pages that are relevant to art. As an actual communication medium we primarily use Facebook.

AD: Aram, killyourphone.com provides relief and a critique of technology. What would your subjects be without the Internet?

AB: Despite rising levels of communication across devices and networks, I nonetheless notice how, when friends express their opinions on the social media channels, they do so ever more consciously and selectively. We’ve come to understand that all of the commentary and spontaneous utterances on Twitter, FB & co no longer just disappear, but are saved, analyzed and used. ‘Private is the new public’, said Geraldine Juarez recently. The belief that the net makes the world fantastically democratic and offers an equal chance for everyone has, at least since Snowden’s revelations, been finally buried. To that extent, the theme ‘how would it be without the Internet?’ is very interesting! How could we communicate without central, monitoring services? Which low-tech DIY technologies are available in order to exchange data ‘offline’? How can we live without Google?… (A self-test is strongly recommended).

The interplay between the old and new environments leads to numerous uncertainties and generational conflicts. While some nostalgic digital immigrants still assess the advantages of the digital world as being synthetic, alien and unsocial, to the generation of digital natives, the digital abundance is felt as entirely natural. For them, the new technologies were with them in the cradle.

AD: Alain, you are a digital immigrant. What was the first media work in your collection? When did you buy it and why?

AL: My first experience with digital art was with bitforms gallery in NY, more than 10 years ago – at a time when it was really under the radar. I went to an exhibition by Mark Napier from whom I acquired a work at that time – one of the “Old Testament” pieces. That was very natural for me, because I was looking for some new kind of art. I knew enough of art history to know that every important movement in art was always linked to a social, economical, technological, psychological development in society. It was a time, when I was trying to collect works that were really addicted/connected to the actual world, the world around us. I was thinking, ok let’s put myself in 2150: when I’ll be using my third heart and my second brain, what will I say was important in the year 1999/ 2000? Without any doubt it will be the computer and the Internet 2.0 with Facebook and social networks and everything. Eventually I thought: wow people were creating art and it is digital. I immediately considered it to be a very important development for the arts.

AD: Wolf, you procure and sell digital art. What do you think today is the greatest obstacle to understanding the effect of new media?

WL: The sale and procurement via the Internet leads to superficiality. This is, at least, my perception. Experiencing art on a website, interactively or not, is often characterized by shorter cycles/loops compared to viewing the same website here in the gallery. I think we need, as we always did, a balance between the real and the virtual. And actually, this makes sense, because we ourselves do embody both. It’s a reason why the digital natives often express themselves in analog media – it’s no coincidence!

AD: Aram, your works stand at the charged interface between public and private, online and offline, between technological infatuation and everyday life, whereby you teach us how to better understand our new environment. ‘ Whoever sharpens our perception tends to [be] antisocial …’, said media theorist Marshall McLuhan. Is it true?

AB: Especially TODAY it is more important than ever to sharpen perception with regard to the effects of technological development. Two and a half years after Snowden the public discussion on privacy and mass surveillance continues to level off. While the big secret services use their hefty budgets to snow us under, and to lock the doors to the NSA, the interest in further explosive leaks from the Snowden documents is fading. ‘Nothing to hide’ is the mantra of the ‘Smart New World’, in which we can neither see nor sense the complex mechanisms of surveillance. In contrast to the dystopic Matrix scenario, our world will ever be fluffier, smarter and more comfortable, unless one has the wrong passport or sits on a bus next to a presumed terrorist. Then reality will be brutal. Precisely for these reasons it is so important to make the hidden, abstract data world understandable, whether through concrete images, objects, or installations. If you were to hold 8 volumes with 4.7 million passwords of LinkedIn users in your hand hand, you would suddenly understand the significance of the security of our online identities.

Copyright has been a relevant topic since the development of the printing press. It grants the author the exclusive right to reproduce, publish, and sell the content and form of intellectual property. The copy & paste mentality of the Internet user brought chaos to the system. The blockchain technology should now manage the author and marketing rights in a way that is more transparent, completely free of Bitcoin and monetary background. The idea had its origin in the art scene.

AD: Alain, do you think the further development of the blockchain lead to more transparency and protection against forgery?

AS: I would not use the word forgery, but certainly [against] an unfair use of material or a copyright infringement. I suppose that the blockchain is one path that should be investigated and tested for the copyright protection of online works of art. I believe in a transformation of the economy of the market for online art towards the direction of a wider distribution through, perhaps, a ‘renting’ of the work rather than an illusory acquisition (taking into account the copyright stays with the artist anyway). i-tunes and Spotify both adapted well to the online art economy.

AD: Wolf, do you make use of these new possibilities within the marketing of digital art? And have you already thought about a new currency model?

WL: I’ve already been confronted by this and I think that it makes sense. With my artists though there’s as yet no need or willingness. I’ve yet to engage with new currency models.

AD: Aram, to what extent is the blockchain and Bitcoin really discussed within artist circles?

AB: Services like Wikipedia, the Open-Source Software movement and, in principle, the entire World Wide Web wouldn’t exist at all today had Telco-payment-services pushed through its fee-based BTX/videotext with pay-per-view, in the 1980s. Naturally the possibility turns the never-ending reproduction of classic markets on its head, and in recent years, there have been extensive debates about copyright and intellectual property. We shouldn’t forget though, that a large part of the software that operates the Internet and millions of devices came about in the spirit of the sharing-culture. The blockchain is a powerful tool, which introduces a form of artificial scarcity into the digital environment. It’s up to each artist himself or herself whether and how he or she chooses to distribute their work. The art market and the demand will certainly create some model or other for the sale and distribution of art that only exists in bits and bytes. Let’s wait and see…

First things first, Antonio Robert is a great guy. He is literally the happiest and most lively artist I’ve ever worked with, his online postings contribute in a full and proper way to both digital art and open source code communities, and he finds space in his wetware for the feedership of cats. He has top-notch glitch credentials, and is hooked into some important ideas about where that field is going – being the most active, if not only ‘glitch artist’ currently showing work in the UK. His work is rooted in glitch aesthetics and ideas, but constantly pushing at its edges. He’s performed and presented at Tate Modern, Databit.me in Arles, France, glitChicago, and he has his first solo show coming up at BOM (Birmingham Open Media) later this year.

Beside his happiness and energy, the first thing you notice about Antonio is that he has this geeky thing going on, like some kind of 90s Spielbergesque computer wizz – I’m sure I heard him call his computer ‘baby’ once as he goded it into action – but when he came to perform as part of our Syndrome programme in Liverpool, he literally ripped his tee-shirt off in the middle of the room, just as he was about to start.

He is the embodiment, in many ways, of the kind of volatility and fun in lots of great glitch art. I hooked up with Antonio online, where we spoke about glitch, and how it relates to his new iconoclastic work on copyright.

NJ: So… first question… You’re kinda out on your own in the UK it seems, as ‘the’ representative of the Glitch Art movement. I can see that that has been really great for you, for example with trips to Chicago etc… but does it also feel a little lonely?!

Antonio: Yeah, definitely. Ever since I helped bring the GLI.TC/H event to the UK/Birmingham in 2011 I’ve been getting questions about giltch art. I’m happy to impart my knowledge and experience to anyone that’s curious and my usual response is “you can do it too!”. That is, if you want to do glitch art there are so many tutorials about it. And, if you want there to be more events focused on glitch art all you need is an idea and some motivation.

NJ: There’s certainly an appetite for work which can reveal the systems underlying digital production – which is what good glitch art does. Do you think it is the term itself which is beginning to feel dated – as a result of an appropriation of its aesthetics? So fewer and fewer artists use this term now because its central modes are being used in a non-critical basis.

Antonio: I think it has become a bit dated through appropriation. That isn’t to say that glitch art has to be a specific thing and made using community-approved techniques, but now I see art that is just noisy or digital-looking that is described as glitch art.

NJ: I want to draw attention to some works of yours – or others – which seek out new (or different) systems which which to destructively engage. Because I think your work is still very much exploring and finding new territories opening up with this trope, while remaining within the ‘glitch’ genre. The work you made for the EVP website, “spɛl ænd spik:” modulated the construction of speech with phonemes. Where does the error enter into this, and do you consider it a departure from your work previous?

Antonio: It’s definitely a departure in terms of aesthetics.

NJ: It is not multicoloured!

Antonio: Hahah yeah. Even my clothes are plain. I wanted the focus to shift from the aesthetics of glitch. Glitch art incorporates many themes including randomness, error, helplessness, the unexpected, machine driven operations. And for the EVP piece I wanted to focus on randomness. I think the error lies in the perceptions of the viewer. When it was exhibited publicly at the Next Wave Exhibition at the RBSA many people thought that it was my voice and, at times, they could hear English words, so, the thing “glitching”, or experiencing an error in this case is their perceptions.

NJ: The tension between the random sounds and the possibility of speech is certainly unsettling.

Antonio: Then there’s the fact that those random sounds are coming from a human image… Digital and “New Media” art is still a new thing for many audiences and institutions, so confusion or bafflement is to be expected. I just hope that this then turns into curiosity. I hope that audiences then begin to ask questions about what it is they’re seeing and how it fits into their ideas about art, creativity and everything else.

NJ: There is something which Bifo Berardi says in “The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance”, where he is noting how ‘political decision has been replaced by techno-linguistic automatisms’, and it seems like ‘glitch’ art has a role to play here which is analogous to the one he assigns poetry in this book. Do you think that the kind of work you do with error is innately political or have revolutionary potential in this way?

Antonio: There is the overtly political work that I have made in the past. For example, Copyright Atrophy, which uses scripts and programs to challenge notions of ownership and copyright, was made specifically to be challenging, as was the work What Revolution. Another theme that interests me is copyright and free culture. And it’s always been there in my work, just not the core message. Now, for example, there is also the work about copyright which is currently being developed (as Archive Remix) as part of my residency at the University of Birmingham. It fits a long tradition of artists remixing artworks and appropriating culture. I’m hoping to bring about a change in attitudes at the university through my work with them.

NJ: Just looking at the work you’re doing at University of Birmingham, it seems to deal with the same theme as Copyright Atrophy, which is a kind of horizon of ownership – which relates also to the horizon of meaning… between meaning and meaninglessness, between owned and apprpriated. So there is a point in the logo-gifs of Copyright Atrophy, and the Archive Remix animations, where they are operating simultaneously as a symbol, or original – and as a new, catachrestic symbol for something yet to be defined. I’m taking the term catachresis here from the way Lee Edelman uses it in his literary and cultural criticism such as No Future, to describe how ‘misuse’ of given words leads to an opening up for heretofore undiscovered territory – also similar to what Rosa Menkman describes as Glitchspeak.

Antonio: Indeed. Although in Copyright Atrophy I am “destroying” the logos, in some way I’m evolving them too. I want to show that a piece of artwork is never truly finished as it may be reinterpreted and remixed by people, and also that we should let this natural evolution happen. Another example to illustrate this evolution is Comic Sans Must DIe.

Yes, I’m destroying each glyph of Comic Sans, but some frames of that might make a good new typeface in itself. The short animations I’m making for Archive Remix are, at the moment, acting as case studies that I will take to the university to show good things can happen when you have more liberal licensing on images. As you may have seen, I also do a version of the animations with the copyrighted material censored. I want to show the perils of censoring. So underneath each “new” gif is one with the copyrighted material blacked out. Imagine if DJ Shadow’s album Entroducing only had works that had been cleared for usage!

NJ: They are sad images, for sure. There is a melancholy at work here, which makes me think of the ‘death’ of the work, being the moment it has to stop evolving.

Antonio: Indeed.

NJ: I feel that way sometimes when I perform a poem, or even read it out to someone on the phone, that somehow its limitations have been reached as potential. Do you think it’s this attitude of a work always being open to interpretation which creates an exit from the inevitably melancholy ending of a completed artwork? I guess that’s one reason why an open platform for the code you produce is attractive.

Antonio: I can see the performance or exhibiting of an artwork as limiting because what has to be presented is something finished. However, sometimes I see this as a chance to exhibit one iteration of the work. It’s always open to myself or others to remake or build on from. There have been people that have built on the code and programs that I make and I’m thankful for this. The best example of this was the method I created for generating jpgs from random data, which was in itself inspired by HEADer Remix by Ted Davis. David Schaffer greatly extended this into his own tool and Holger Ballweg ported the code into SuperCollider. If any code I write inspires others who am I to stop them from using or building on it?

NJ: A year or so ago, I proposed that art forgery should be legalised. I feel, along with many others, that the ‘art market’ has very little to do with the community of artists most worthy of admiration and respect. But perhaps it is ownership itself that is the problem. What is there in ownership ‘authorship’ which is valuable to retain? Attribution, I suppose – but what value in attribution?

Antonio: Yes, attribution is the important thing. All people should rightfully own the thing that they make. But problems arise because they then want to own everything that comes after it. So yes, remixes, reinterpretations are important and should be allowed, just as long as the original author is attributed for their work. It’s all a confusing and scary time for artists and the art world. Everyone’s wondering how they can make money and sustain their practice whilst still reaching as many people as possible. I hope that through my work I can show that these new approaches (open source, free culture, liberal licensing etc) can yield positive results and won’t necessarily result in the loss of earnings or opportunities.

NJ: It’s kind of ironic though, isn’t it, that digital artists like yourself who actively question and disrupt the basis of the apparently ‘infinite flows’ of digital content, finance… are part of a scene whose infrastructure itself is crumbling, and who generally suffer a very real stress and insecurity as a result. This is exacerbated as well by the kind of funding environment which might be offsetting this instability somewhat, but where digital artists are co-opted ecosystem of ‘digital economy’ — rather than a ‘cultural economy’ — itself formed around ideas of efficiency, and hence ‘labour savings’? Do you think this might actually be harmful?

Antonio: Yes, I think it’s dangerous focusing just on digital economy and making everything digital. Sure, it’s exciting that technology brings us all of these opportunities, but it leaves behind everyone that doesn’t work in that way.

NJ: Finally, on this subject, I thought you might like to highlight some contemporary work which influences you, which comes from outside the ‘digital art’ scene (if this is even possible!) and thus contributes to the ecosystem of digital innovation, in more traditional forms.

Antonio: One of my influences was Arturo Herrea’s 2007 exhibition at the Ikon Gallery. I loved the way there was order in the chaos. Outside of that it’s really difficult to find examples of influential work that isn’t in some way digital. A lot of the live performance, sculpture and video work that inspires me is often not only made using digital technology – 3D printing, projection etc – but is about digital and internet culture.

You can follow Antonio on

http://www.hellocatfood.com/http://hellocatfood.tumblr.com/

and https://twitter.com/hellocatfood

and Nathan is at https://twitter.com/nathmercy