A Computer in the Art Room: The Origins of British Computer Arts 1950-1980

Catherine Mason

ISBN: 1899163891

JJG Publishing 2008

Computing anywhere else but its history often seems like a carefully guarded secret. This has been alleviated by activity around the resurrected Computer Arts Society in the 2000s, notably the acquisition of CAS’s archives by the V&A and the CaCHE project at Birbeck College which ran from 2002-2005. CaCHE, run by Paul Brown, Charlie Gere, Nick Lambert and Catherine Mason, produced conferences, exhibitions, and publications including the book “A Computer In the Art Room”, by Mason.

The art room of the title is the art department of British educational institutions prior to art becoming a degree-level subject. From the 1950s to the 1970s, when the cost of computing machinery dropped from the level where only major government and corporate organizations could afford them to the level where you only needed a second mortgage to afford one, the best way for artists to get access to the enabling technology of computing machinery was usually in an educational institution.

Mason starts out by describing the artistic and art educational situation in the UK at the time of the Festival Of Britain and the foundation of the ICA in London in the early 1950s. She then explains the structure and significance of the emergence of Basic Design teaching, the impact of the Coldstream report on art education, and the rise of the polytechnic colleges over the next thirty years. This provides vital context for the emergence of art computing teaching in the UK. It is also of more general interest for British art history. Conceptualism, performance, Land Art, the Hornsey Art School occupation, and the educational and media graphics that are currently being used as the basis of “hauntological” art all share this background and can better be understood and critiqued with better knowledge of it.

Basic Design courses started in London but didn’t remain there for long. They spread and matured throughout the UK, becoming entangled with the earliest teaching of art computing in provincial technical colleges. Mason traces the family trees of art computing teaching over time through these institutions and back to London-based institutions. Some of the names are familiar from art history (Richard Hamilton, Stephen Willats), some from art computing history (Harold Cohen, John Latham). Where the people involved cross over with cybernetic art, Conceptualism or other artistic currents Mason shows how their ideas fed into and from their art computing work.

The conceptual content of art computing followed the Bauhaus, cybernetics, systems, sociological and environmental influences on art from the 1950s to the 1970s. Its technological forms likewise followed those of mainstream computing. In the 1960s time was leased on mainframes or computers were built by hand. In the 1970s, minicomputers became available and art domain-specific software frameworks or programming languages were written by their users. In the 1980s, workstations with touch tablets, framebuffers, and increasingly proprietary software brought previously unprecedented power and ease of use at the cost of more fixed forms.

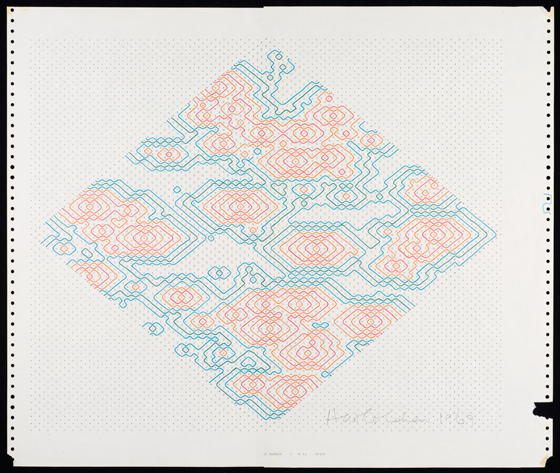

The history that I had to piece together as a student from hearsay and from hints in old publications, of the PICASO graphics language at Middlesex University that I found a print-out of the manual for when I was there in the 1990s, of Art & Language’s use of mainframe computers, of early cross-overs between art computing and dance, of cybernetic systems and games that attracted mass audiences before disappearing, is detailed, illustrated and contextualized in page after page of descriptions of hardware, software, institutions, courses and projects. The detail would be overwhelming where it not for Mason’s ability to bring the human and broader cultural aspect of it all to life.

There’s Jasia Reichardt’s Cybernetic Serendipity show at the ICA, Andy Inakhowitz’s Senster robot, John Latham’s dance notation experiments, The Environment Game, and computer graphics drawn with the languages and environments developed in UK art institutions. There’s pictures of the computer systems at the Slade, the RCA, Wimbledon and other art schools that serve as insights into the artists’ studios. There’s the Computer Arts Society, IRAT, APG. And, crucially, there’s the links between them told in a narrative that is coherent while still presenting the breaks and false starts in the story.

The history of “A Computer In The Art Room” reads all too often as brief moments of individuals triumphing against the odds to produce key works of art computing then fading into obscurity, academia or commerce. But any art history that considers a specific context at such a level of detail will look like this. Mason describes works, institutions and artists that deserve broader recognition, although she is under no illusion about how far the road to that recognition may be, citing the example of how long it has taken for photography to be recognized as art in the culturally conservative UK.

The social and pedagogical changes of the period covered by “A Computer In The Art Room” reflect a time of hope and ambition for education in society that made the academy less remote. Mason provides the social, technological and educational context needed to appreciate the very real achievements of art computing that she describes against this backdrop. As a slice of art history this is richly detailed. It touches on subjects far beyond art computing that will help any art student of history better understand the period covered. And it is both a relief and an inspiration to finally have a public record of this important aspect of the history of art computing in the UK.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

The Zero Dollar Laptop Workshop programme has been developed and delivered through partnership between Furtherfield and Access Space and aims to change attitudes to technology. It does this by recycling hardware, deploying Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), sharing skills and working together to create rich media content.

This project has provided a useful basis for thinking about how art might be able to create change through learning and education that relates to technology.

This question becomes especially relevant in the context of current, global economic and ecological collapse.

So first let’s start by thinking about what art and technology and social change have got to do with each other?

It does depend on how you view art. At Furtherfield we don’t accept the mainstream view of art as a marginal interest. The expanded, connected and networked art forms that we choose to work with cannot be separated from life so easily.

They engage the people who encounter them with different kinds of aesthetic, ethical and philosophical experiences – often in places not easily recognisable as art-spaces, often in technologically enabled spaces because this is where life takes place for so many people.

For all kinds of reasons (to do with our education and class structures), in the UK the dominant view is that ‘great’ art is separate and distant from the rest of life and therefore of marginal relevance to society and most people, or to quote Heath Bunting ‘Most art means nothing to most people’.

It is regarded as: elite/intellectual, historical/heritage, commodity, the work of charlatans etc.

Sometimes art is regarded perhaps more positively, as a diversion or a hobby; more positive from our point of view because people make art their own, share it and incorporate it into their own lives on their own terms.

Don’t just Do It Yourself, Do It With Others (DIWO!)

Furtherfield got started in the context of the discourse-smothering London Brit Art gallery scene in the mid-90s, when access to established galleries was carefully guarded. Meanwhile the Internet, an open public space of unlimited dimensions, was relatively sparsely populated at two extremes by corporate marketing departments and pet owners. The Internet also offered a free playground for early net artists.

Since then Furtherfield has co-constructed platforms and processes (online and in physical spaces) with a network of other artists, hackers, gamers, programmers, thinkers and curators to support collaboration and engagement between artists, participants and audiences worldwide.

Informed by ‘open and free’ philosophies and practices of peer-to-peer cultural development and moving on from the DIY (Do It Yourself) approach of the 1990s artist-hackers that fed on the Modernist understanding of the individual artistic genius, we have moved towards more collaborative processes that we call DIWO (Do It With Others) and that explore different ways of creating shared visions.

For us taking a grassroots approach in art means that we pay attention to the everyday lives of the people we work with, to create and shape the platforms that we need. This is not a hippy dream. Rather, it provides a way to develop robust and healthy ways for diverse people and interests to interact and co-exist for mutual benefit.

Since 2008 Furtherfield and Access Space have worked in partnership on the Zero Dollar Laptop project, to support cooperation in creativity, technical learning and environmental awareness. One side-effect of techno-consumerism is that we dump tonnes of UK electronic waste in the developing world each year.[2]

This project, inspired by James Wallbank’s Zero Dollar Laptop Manifesto, aims to change the way we think about technology by a shift of emphasis: from high-status consumer technologies to customised tools-for-the-job and smart, connected users.

Our organisations have worked together with participants to develop resources and pilot workshops that aim to eventually bring back into use (or save from toxic waste dumps) millions of redundant laptops currently gathering dust on shelves in homes and offices across Britain; putting them in the hands of the people who are best placed to make use of them, to benefit from a collaborative approach to learning and to connect with new knowledge networks in the process.

This project has its basis in grassroots, critical practice at the intersection of art, technology and social change.

The first pilot of Zero Dollar Laptop workshops kicked off at the Bridge Resource Centre in West London in January 2010 with clients of St Mungo’s Charity for Homeless People. [3]

In our experience, a much more diverse group of people are able to enjoy and benefit from technical projects when the projects acknowledge and incorporate ethical, philosophical and aesthetic questions as part of the mix.

People who might not initially identify themselves as ‘techy’ stay engaged with complex technical learning processes by focusing on the learning that is meaningful for them and sharing it with others.

In the case of Zero Dollar Laptop workshops this can range from creating a profile image for Facebook to writing a blog post to lobby against government cuts in public services, or creating a desktop background or a new startup-sound to customise their own laptop.

The meaning and function of work is often conveyed by the construction of a context (a place, a set of tools, an aesthetic, a set of relationships) or a hack or remix of an existing context.

With participatory or collaborative artworks the context in which people engage with the work is a part of the work.

So the role of the artist today has to be to push back at existing infrastructures, claim agency and share the tools with others to reclaim, shape and hack these contexts in which culture is created.

We believe that through creative and critical engagement with practices in art and technology people become active co-creators of their cultures and societies.

And as James Wallbank notes, ‘the best artworks are those that create artists’.

Originally commissioned by Axisweb.

In 2002, when Monochrom was invited to act as the representative of Austria at the Sao Paulo Biennial, instead of going as yourselves, you sent Georg Paul Thomann, one of the country’s most prominent avant guard artists, and also a complete fabrication.

Yes, we were asked to represent the Republic of Austria at the Sao Paulo Art Biennial, Sao Paulo (Brazil) in 2002. However, the political climate in Austria (at that time, the center-right People’s Party had recently formed a coalition with Jorg Haider’s radical-right Austrian Freedom Party) gave us concerns about acting as wholehearted representatives of our bloody nation. We dealt with the conundrum by creating the persona of Georg P. Thomann, an irascible, controversial (and completely fictitious) artist of longstanding fame and renown. Through the implementation of this ironic mechanism – even the catalogue included the biography of the non-existent artist – we tried to solve with pure fiction the philosophical and bureaucratic dilemma attached to the system of representation.

It gave me something of a hearty guffaw to hear about how you and your fellows, manning the Austria country booth as the artist’s technical support staff – the lowliest of low in the art world hierarchy – went about revealing the fictitious nature of the artist.

Yes, we turned the tables. When members of the administration, journalists, or curators asked about the whereabouts of Thomann, our irritated answer was that he hadn’t cared to show up so far, and that he hadn’t helped with anything, because he was supposedly watching porn in his hotel room all day, while we – the members of his technical crew – didn’t care about that bullshit at all. But we informed other technical support teams about the basic idea of the project. They were also given detailed information about Thomann’s non-existence but we did not give them any hierarchic directives about what to do with their knowledge but left it up to them if they wanted to reveal the fake or keep spinning the story. Most people enjoyed doing the latter and they also kept telling different versions of the heard information until finally a bubbling geyser kept erupting in various ways and constantly led to new outbreaks of tittle-tattle.

What happened next, as I heard you describe it, was that “bubbles and bubbles of rumors” began to form around the expansive floor of the biennial. I found this moment in the arc of the project to be particularly interesting and was hoping you could perhaps share some of your thoughts and recollections.

Let’s give you a brief summary of the background. The basic principles of an art-super-structure like a Biennial is simple: lots of little white boxes in which art was set up – and little artists, spreading business cards like prayers. There is a nice German term: “die Warenformigkeit des Kunstlers” (“the commodity value of the artist”). We hardly had any contact with other artists… and that was bad. They came from more than 80 different countries, but they were hiding in their white boxes. Everyone was busy building his or her own little world. Then, during the final setup phase we found out about an incident, which took place in our neighborhood through a copied note.

One year before the Biennial, Chien-Chi Chang had been invited to be the official representative of Taiwan at the Biennial. But then, three days before the opening, his caption – adhesive letters – had been removed from his cube virtually over night. ‘Taiwan’ was replaced with ‘Museum of Fine Arts Taipeh.’ But to Chien-Chi Chang the status as an official representative of Taiwan was very important, because his photography artwork dealt directly with the inhumane psychiatric system in Taiwan.

Chien-Chi was trying to get in contact with the Biennial administration and the chief curator (the German Alfons Hug), but didn’t succeed. Communication was refused. After that he decided to write an open letter, but the creative inhabitants of all the little white art-combs didn’t seem too interested in the artist’s chagrin, who by now wanted to leave the Biennial out of protest.

We were interested in the situation and did some research. We found out that the Chinese delegation had threatened to withdraw their contribution and to cause massive diplomatic problems. To them, Taiwan was clearly not an independent country (c/f ‘One China Policy’) and they put pressure on the Biennial management to get that message out. The management did not make this international scandal public and it was quite obvious why.

monochrom decided to show solidarity with Chien-Chi. We wanted to set an example and show that artists do not necessarily have to internalize the fragmentation and isolation that is being imposed upon them by the structure of the art market, the exhibition business, as well as the economy containing them. For us, though, this is not about taking a stand for either the westernized-economical imperialism represented by Taiwan or for China’s old-school Stalinist imperialism. This is about integrity and solidarity, values that we chose to express through a collaborative act. Together with other artists from various countries we launched a solidarity campaign: we took off some adhesive letters of each collaborating country’s signature and donated them to Chien-Chi Chang. monochrom sponsored the ‘t’ of Austria, while the Canadians donated one of their three as. The other participating artists were from Croatia, Singapore, Puerto Rico and Panama. A lot of artists and curators from other countries refused to support the campaign for fear of – as they would call it – “negative consequences.” WTF? But at least some of the artists were pulled out of their self-referential and insular national representation cubes which, in themselves, so rigorously symbolized the artists’ work and his or her persona as commodities.

After some time we managed to attach a trashy, yet legible ‘Taiwan’ to the outside wall of Chien-Chi Chan’s cube. Numerous journalists took notice of the campaign and Chien-Chi opened his exhibition in front of a cheering audience. Some days later, we found out that Chinese and Taiwanese newspapers massively covered the campaign. One Taiwanese paper used the headline “Austrian artist Georg Paul Thomann saves ‘Taiwan’.” In other words, a non-existing artist saved a country pressed into non-visibility. Who said that postmodernism can’t be radical?

What was it like – even from a kind of phenomenological sense – to be in the midst of this bubbling, to experience the formation of a scandal from its very embryonic moments? Is there something in the interiority of situations like this that you see as essential to the creation of new kinds of solidarity?

First we would have to define what “new kinds of solidarity” mean. What would be the ‘new’ part of it? Does it go beyond old and traditional forms of solidarity? And why should it? I think that classic forms of solidarity were carried out by political groups or other collective entities. They tried to express their (let’s label it as) “old-school solidarity” by pointing their collective fingers at someone who they thought were mistreated: “Look, look this human being is being oppressed!” And they always did it “in the name of something”. Old-school solidarity was one more frickin’ medium that people used to get a message across. Thus it was always part of the realm of representation. Your act of solidarity represents the one you show solidarity with, but your act is also advertisement for yourself, your cause and the (political) identity you wish to construct. Politics is always drama. Best example for this would be the “supporters of Palestine”. There are tons of ethnic groups on this rusty little planet who have to suffer under worse conditions. But nobody seems to be interested in showing solidarity with them. Where are Henning Mankell and Noam Chomsky when you really need them? Involved in some stupid fast-food anti-imperialism. We have to understand that the “object of solidarity” is something you pick for a reason… and most of the time it’s to feel good as a group and to impress your peers. But that has nothing to do with factual, non-reductionist political analysis. Collective entities define themselves through acts of representation and this representation is comparable to the construction of national pride or patriarchal family structures and values. Solidarity can be read as an act of defining identities. And that can be very dangerous, because old school solidarity always wants to be “right”. You are always “the good one” supporting the poor bastards. Smash dichotomies!

What we experienced at the Biennial of Sao Paulo back in the spring of 2002 was a very non-collective act. We were no real group, no leaflets, we had no common agenda, we were a psycho-geographic swarm. There was no basis for acting or speaking as a collective and there was no need to bundle our powers or form an identity. Yes, we tried to recruit other artists to join in our little act of solidarity. But it was no protest, we didn’t protest a certain political agenda because we didn’t want to end up in the old black and white world that, for example, all the apeshit Pro-Tibet supporters live in. Bah! Their ugly flags! Their patriarchal projections! Richard Gere! Yuck! So it was a kind of “free flowing solidarity”, not to be abused to form a political movement or statement. The only form of identity that was formed was the simple idea that even bourgeois artists can decide whether they want to be part of the Biennial and its stupid rules or whether they want to be part of action and fun.

To make it short: we are interested in micro-political solidarity, temporary solidarity that can’t fossilize. Solidarity is important if it can evolve and vanish within a short span of time and all that’s left is rumors and vague commemorations. Let’s call it a process of counteracting – that might be well-known in the field of the urban guerrilla but that so rarely pops up at art shows.

Read Part 1 of the Interview

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/interview-johannes-grenzfurthner-monochrom-part-1

Read Part 3 of the Interview

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/interview-johannes-grenzfurthner-monochrom-part-3

Co-published by Furtherfield and The Hyperliterature Exchange.

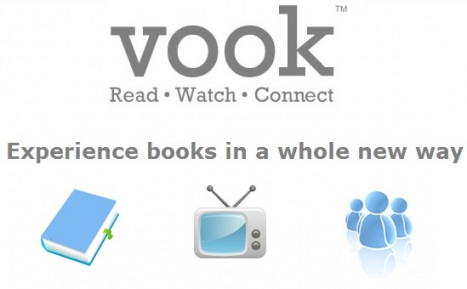

Last October I received an e-mail headed “Introducing Vook”:

The Vook Team is pleased to announce the launch of our first vooks, all published in partnership with Atria, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. These four titles… elegantly realize Vook’s mission: to blend a book with videos into one complete, instructive and entertaining story.

The e-mail also included a link to an article about Vooks in the New York Times:

Some publishers say this kind of multimedia hybrid is necessary to lure modern readers who crave something different. But reading experts question whether fiddling with the parameters of books ultimately degrades the act of reading…

Note the rather loaded use of the words “lure”, “crave”, “fiddling” and “degrades”. The phraseology seems to suggest that modern readers are decadent and listless thrill-seekers who can scarcely summon the energy to glance at a line of text, let alone plough their way through an entire book. If an artistic medium doesn’t offer them some form of instant gratification – glamour, violence, excitement, pounding beats, lurid colours, instant melodrama – then it simply won’t get their attention. But publishers have a moral duty not to pander to their readers’ base appetites: the New York Times article ends by quoting a sceptical “traditional” author called Walter Mosley –

“Reading is one of the few experiences we have outside of relationships in which our cognitive abilities grow,” Mr. Mosley said. “And our cognitive abilities actually go backwards when we’re watching television or doing stuff on computers.”

In other words, reading from the printed page is better for your mental health than watching moving pictures on a screen: an argument which has been resurfacing in one form or another at least since television-watching started to dominate everyday life in the USA and Europe back in the 1950s. To some extent this is the self-defence of a book-loving and academically-inclined intelligensia against the indifference or hostility of popular culture – but in the context of a discussion of Vooks, it can also be interpreted as a cry of irritation from a publishing industry which is increasingly finding the ground being scooped from under its feet by younger, sexier, more attention-grabbing forms of entertainment.

The fact that the Vook publicity-email links to an article which is generally rather sniffy and unfavourable about the idea of combining video with print no doubt reflects a belief that all publicity is good publicity – but it is also indicative of the publishing industry’s mixed attitudes towards the digital revolution. On the whole, up until recently, they have tended to simply wish it would just go away; but they have also wished, sporadically, that they could grab themselves a piece of the action. But those publishers who have attempted to ride the digital surf rather than defy the tide have generally put their efforts and resources into re-packaging literature instead of re-thinking it: and the evidence of this is that the recent history of the publishing industry is littered with ebooks and e-readers, whereas attempts to exploit the digital environment by combining text with other media in new ways have generally been ignored by the publishing mainstream, and have therefore remained confined to the academic and experimental fringes.

The publishing industry’s determination to make the digital revolution go away by ignoring it has been even more evident in the UK than in the US. The 1997 edition of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, for example, contains no references to ebooks or digital publishing whatsoever, although it does contain items about word-processing and dot-matrix printers. On the other hand, Wired magazine was already publishing an in-depth article about ebooks in 1998 (“Ex Libris” by Steve Silberman, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/6.07/es_ebooks.html) which describes the genesis of the SoftBook, the RocketBook and the EveryBook, as well as alluding to their predecessor, the Sony BookMan (launched in 1991). Even in the USA, however, enthusiasm for ebooks took a tremendous knock from the dot-com crash of 2000. Stephen Cole, writing about ebooks in the 2010 edition of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, summarises their history as follows:

Ebook devices first appeared as reading gadgets in science fiction novels and television series… But it was not until the late 1990s that dedicated ebook devices were marketed commercially in the USA… A stock market correction in 2000, combined with the generally poor adoption of downloadable books, sapped all available investment capital away from internet technology companies, leaving a wasteland of broken dreams in its wake. Over the next two years, over a billion dollars was written off the value of ebook companies, large and small.

After 2000, there was a widely-held view (which I shared) that the ebook experiment had been tried and failed: paper books were a superb piece of technology, and perhaps a digital replacement for them was simply never going to happen. There were numerous problems with ebooks: too many different and incompatible formats, too difficult to bookmark, screens hard to read in direct sunlight, couldn’t be taken into the bath, etc. But ebooks have always had a couple of big points in their favour – you can store hundreds on a computer, whereas the same books in paper form demand both physical space and shelving, you can find them quickly once you’ve got them, and they’re cheap to produce and deliver. Despite the dot-com crash and general indifference of the reading public, publishers continued to bring out electronic editions of books, and a small but growing number of people continued to download them.

Things really started to change with the launch of Amazon’s Kindle First Generation in 2007. It sold out in five and a half hours. With the Kindle, the e-reader went wireless. Instead of having to buy books on CDs or cartridges and slot them into hand-helds, or download them onto computers and then transfer them, readers using the Kindle could go right online using a dedicated network called the Whispernet, and get themselves content from the Kindle store.

Despite this big step forward, the Kindle was still an old-school e-reader in some respects: it had a black and white display, and very limited multimedia capabilities. The Apple iPad changed the rules again when it was launched in April 2010. The iPad isn’t just an e-reader – it’s “a tablet computer… particularly marketed for consumption of media such as books and periodicals, movies, music, and games, and for general web and e-mail access” (Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I-pad). Its display screen is in colour, and it can play MP3s and videos or browse the Web as well as displaying text. For another thing, it goes a long way towards scrapping the rule that each e-reader can only display books in its own proprietary format. The iPad has its own bookstore – iBooks – but it also runs a Kindle app, meaning that iPad owners can buy and display Kindle content if they wish.

It seems we may finally be reaching the point where ebooks are going to pose a genuine challenge to print-and-paper. Amazon have just announced that Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has become the first ebook to sell more than a million copies; and also that they are now selling more copies of ebooks than books in hardcover.

It is certainly also significant that the past couple of years have seen a sudden upsurge of interest in the question of who owns the rights over digitised book content, and whether ordinary copyright laws apply to online text – a debate which has been brought to the boil by a court case brought against Google in 2005 by the Authors Guild of America.

In 2002, under the title of “The Google Books Library Project”, Google began to digitise the collections of a number of university libraries in the USA (with the libraries’ agreement). Google describes this project as being “like a card catalogue” – in other words, primarily displaying bibliographic information about books rather than their actual contents. “The Library Project’s aim is simple”, says Google: “make it easier for people to find relevant books – specifically, books they wouldn’t find any other way such as those that are out of print – while carefully respecting authors’ and publishers’ copyrights.” They do concede, however, that the project includes more than bibliographic information in some instances: “If the book is out of copyright, you’ll be able to view and download the entire book.” (http://books.google.com/googlebooks/library.html)

In 2004 Google launched Book Search, which is described as “a book marketing program”, but structured in a very similar way to the Library Project: displaying “basic bibliographic information about the book plus a few snippets”; or a “limited preview” if the copyright holder has given permission, or full texts for books which are out of copyright – in all cases with links to places online where the books can be bought. Interestingly, my own book Outcasts from Eden is viewable online in its entirety, although it is neither out of copyright nor out of print, which casts a certain amount of doubt on Google’s claim to be “carefully respecting authors’ and publishers’ copyrights”.

In 2005 the Authors Guild of America, closely followed by the Association of American Publishers, took Google to court on the basis that books in copyright were being digitised – and short extracts shown – without the agreement of the rightsholders. Google suspended its digitisation programme but responded that displaying “snippets” of copyright text was “fair use” under American copyright law. In October 2008 Google agreed to pay $125 million to settle the lawsuit – $45.5 million in legal fees, $45 million to “rightsholders” whose rights had already been infringed, and “$34.5 million to create a Book Rights Registry, a form of copyright collective to collect revenues from Google and dispense them to the rightsholders. In exchange, the agreement released Google and its library partners from liability for its book digitization.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Book_Search_Settlement_Agreement). The settlement was queried by the Department of Justice, and a revised version was published in November 2009, which is still awaiting approval at the time of writing.

The settlement is a complex one, but its most important provision as regards the future of publishing seems to be that “Google is authorised to sell online access to books (but only to users in the USA). For example, it can sell subscriptions to its database of digitised books to institutions and can sell online access to individual books.” 63% of the revenue thus generated must be passed on to “rightsholders” via the new Registry. “The settlement does not allow Google or its licensees to print copies of books in copyright.” (“The Google Settlement” by Mark Le Fanu, The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook 2010, pp. 631-635).

Google, it will be noted, are now legally within their rights to continue their digitisation programme. This means they don’t have to ask anyone’s permission before they digitise work. If authors or publishers would prefer not to be listed by Google it is up to them to lodge an objection online. Google would argue that in launching their Library Project and Books Search they have merely been seeking to make their search facilities more complete, and thus to “make it easier for people to find relevant books” – but whether or not they have been deliberately plotting their course with wider strategic issues in mind, the end result has been to make them the biggest single player – almost the monopoly-holder – where digital book rights are concerned. As a reflection of this, an organisation called the Open Book Alliance has been set up to oppose the settlement, supported by the likes of Amazon and Yahoo: “In short,” their website claims, “Google’s book digitization strategy in the U.S. has focused on creating an impenetrable content monopoly that violates copyright laws and builds an unfair and legally insurmountable lead over competitors.” (http://www.openbookalliance.org/)

Whatever the pros and cons of the Google Settlement, it has undoubtedly helped to focus the minds of writers and publishers alike on the question of digital rights. Copyright laws and publishers’ contracts were designed to deal with print and paper, and until very recently there has been almost no reference at all to electronic publication. Writers who have agreed terms with a publisher for reproduction of their work in print have theoretically been at liberty to re-publish the same work on their own websites, or perhaps even to collect another fee for it from a digital publisher; and conversely, publishers who have signed a contract to bring out an author’s work in print have sometimes felt free to reproduce it electronically as well, without asking the writer’s permission or paying any extra money.

But things are beginning to change. A June 2010 article in The Bookseller notes that Andrew Wylie, one of the most prestigious of UK literary agents, “is threatening to bypass publishers and license his authors’ ebook rights directly to Google, Amazon or Apple because he is unhappy with publishers’ terms.” This is partly because he believes electronic rights are being sold too cheaply to the likes of Apple: “The music industry did itself in by taking its profitability and allocating it to device holders… Why should someone who makes a machine – the iPod, which is the contemporary equivalent of a jukebox – take all the profit?” Clearly, electronic rights are going to be taken much more seriously from now on.

Further indications that authors, publishers and agents are beginning to wake up and smell the digital coffee can be found in the latest editions of The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook and The Writers’ Handbook. For those who are unfamiliar with them, these annual publications are the UK’s two main guides to the writing industry. The 2010 edition of The Writer’s Handbook opens with a keynote article from the editor, Barry Turner, entitled “And Then There was Google”. As the title indicates, its main subject is the Google settlement and its implications – but its broader theme is that the book trade has been ignoring the digital revolution for too long, and can afford to do so no longer:

In the States… sales of e-books are increasing by 50 per cent per year while conventional book sales are static. An indication of what is in store was provided at last year’s Frankfurt Book Fair where a survey of book-buying professionals found that 40 per cent believe that digital sales, regardless of format, will surpass ink on paper within a decade.

The Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook is more conservative in tone, but if anything its coverage is more in-depth. It has an entire section titled “Writers and Artists Online”, which leads with an article about the Google settlement. In addition there are articles on “Marketing Yourself Online”, “E-publishing” and “Ebooks”. Even in the more general sections of the Yearbook there is a widespread awareness of how digital developments are affecting the book trade. For example, there is a review (by Tom Tivnan) of the previous twelve months in the publishing industry, which acknowledges the importance not just of ebooks but print-on-demand:

Amazon’s increasing power underscores how crucial the digital arena is for publishing… Ebooks remain a miniscule part of the market,… yet publishers and booksellers say they are pleasantly surprised at the amount of sales… And it is not all ebooks. The rise of print-on-demand (POD) technology (basically keeping digital files of books to be printed only when a customer orders it) means that the so-called “long tail” has lengthened, with books rarely going out of print… POD may soon be coming to your local bookshop. In April 2009, academic chain Blackwell had the UK launch of the snazzy in-store Espresso POD machine, which can print a book in about four minutes…

There is also an article about “Books Published from Blogs” (by Scott Pack):

Agents are proving quite proactive when it comes to bloggers. Some of the more savvy ones are identifying blogs with a buzz behind them and approaching the authors with the lure of a possible book deal… Many bestsellers in the years to come will have started out online.

Most of the emphasis in these articles falls on the impact which digital developments are having on the marketing of books rather than the practice of writing itself. But now and again there are signs of a creeping awareness that digitisation may actually change the ways in which our literature is created and consumed. In The Writer’s Handbook, Barry Turner attempts to predict how the digital environment may affect the practice of writing in the coming years:

Those of us who make any sort of livng from writing will have to get used to a whole new way of reaching out to readers. Start with the novel. Most fiction comes in king-sized packages… Publishers demand a product that looks value for money… But all will be different when we get into e-books. There will be no obvious advantage in stretching out a novel because size will not be immediately apparent… Expect the short story to make a comeback… The two categories of books in the forefront of change are reference and travel. Their survival… is tied to a combination of online and print. Any reference or travel book without a website is in trouble, maybe not now, but soon.

Scott Pack’s article on “Books Published from Blogs” tends to focus on those aspects of a blog which may need remoulding to suit publication in book form; but an article by Isabella Pereira entitled “Writing a blog” is more enthusiastic about the blog as a form in its own right:

The glory of blogging lies not just in its immediacy but in its lack of rules… The best bloggers can open a window into private worlds and passions, or provide a blast of fresh air in an era when corporate giants control most of our media… Use lots of links – links uniquely enrich writing for the web and readers expect them… What about pictures? You can get away without them but it would be a shame not to use photos to make the most of the web’s all-singing, all-dancing capacities.

Even here, however, the advice stops short of videos, sound-effects or animations. Another article in The Writers’ and Artists’ Handbook (“Setting up a Website”, by Jane Dorner) specifically forbids the use of animations:

Bullet points or graphic elements help pick out key words but animations should be avoided. Studies show that the message is lost when television images fail to reinforce spoken words. The same is true of the web.

It’s a little difficult to fathom exactly what point Dorner is trying to make here, but it seems to be something along the lines that using more than one medium may have a distracting rather than enhancing effect. If the spoken words on your television are telling you one thing, but the pictures are telling you another, then “the message is lost”. Perhaps a more interesting point, however, is where Dorner draws her dividing-line between acceptable and unacceptable practice. “Bullet points or graphic elements” are all right, because they “help pick out key words”, but “animations should be avoided”. In other words visual aids are all very well as long as they remain to subservient to text. They minute they threaten to replace it as the focus of attention, they become undesireable.

Clearly this point of view continues to enjoy a lot of support, particularly from traditionalists in the writing and publishing industries. All the same, combinations of text with other media may be about to enjoy some kind of vogue; and the development of the Vook brand since its launch last October is an instructive case-history in this regard.

When Vooks were first launched it seems fair to say that they were broadly greeted with a mixture of indifference and scorn. Reviews which appeared in the first couple of months after the launch were usually either lukewarm of downright unfavourable. Here, for example, is one from Janet Cloninger, writing in The Gadgeteer, November 2009:

So how were the video clips? Have you ever seen any of those old 60s TV shows where they were trying to show a bad acid trip? You know the crazy camera work, the weird color changes, the really bad acting?… I don’t think they added anything to the story at all… I found they were very distracting while trying to read.

Here is another from the Institute for the Future of the Book:

In terms of form the result is ho-hum in the extreme, particularly as there doesn’t seem to be much attempt to integrate the text and the banal video, which seems to exist simply to pretty-up the pages.

Following on from this generally unenthusiastic reception for the first Vooks, news about the brand over the next few months seemed to suggest that it was struggling to establish itself. In January 2010 Vook announced that they were publishing a range of “classic” titles, mostly for children – since “classic” normally means “out of copyright”, this seemed to imply that they were trying to boost their titles-list on the cheap. In February there was an announcement that Vook had raised an extra $2.5 million in “seed-financing” from a number of Silicon Valley and New York investors, suggesting that perhaps initial sales had been disappointing, Simon & Schuster had been reluctant to put up more money, and new sources of finance had therefore been sought.

With the launch of the iPad, however, it became obvious that Vook was making another throw of the dice. In April they launched 19 titles specially adapted for the iPad: In a statement, Bradley Inman, Vook CEO and founder said, “We will remember the iPad launch as the day that the publishing industry officially made the leap to mixed-media digital formats and never looked back…” The Vook blog makes this pinning-of-hopes on the iPad even more apparent:

The release of the iPad this Saturday was not just a red letter moment for Silicon Valley, it marked a turning point for the publishing and film industries, and a great opportunity for those invested in the future of media. The team at Vook has been working hard for months to prepare apps for submission to Apple… In many ways, it seems like the iPad was literally made for us…

And it seems their hopes may not have been misplaced. In May they launched a title about Guns’n’Roses (Reckless Road, documenting the creation of the Appetite for Destruction album), and lo and behold it was favourably greeted:

…unprecedented photos and memorabilia from the early years of one of the great rock bands from the 1980s and 1990s… If you are a true hard rock fan, and Guns ‘N’ Roses was one of your favorite bands, this app is worth the try. (PadGadget)

Now that I’ve had some time to read through Reckless Road and watch many of the videos included in it I can see the value of the Vook approach. It lends itself well to a product like this… This is an app any Guns N’ Roses fan would greatly appreciate. (Joe Wickert)

In June, the Vook version of Brad Meltzer’s bestseller Heroes for my Son was also favourably received:

It is easy to see the tremendous possibilities in the Vook format, especially when tied to a tablet device like the iPad. I very much enjoyed my first experience with a Vook mainly because I rapidly dropped my attempt to think of it as a Book with video plug ins. A Vook is really a multimedia platform that centers around text, rather than a traditional book. (MobilitySite)

Both these books are non-fiction – a genre in which the relationship between video footage and text seems far less problematic. It is interesting to note, however, that in both cases the non-linear structure of the Vook is singled out as a positive feature, compared to the sequential organisation of a traditional book:

It is charmingly non-linear and can be approached from many different angles. More a chocolate box than a book, especially if you are like me and enjoy really digging down into a subject while reading. (MobilitySite)

Remember that old VH1 series, Behind the Music? Canter’s Vook app feels like a modern version of that approach, with the added benefit that you can hop around the story to your heart’s content… (Joe Wickert)

There are hints here of a realisation that digital media can sometimes offer kinds of reading which are unavailable to, or hampered by, traditional print-and-paper.

Further recognition that ebooks with multimedia in them might actually have market appeal came at the end of June from none other than Amazon, who announced that they were adding audio and video to the Kindle iPhone/iPad app. The irony of this move is, of course, that Kindle ebooks are now multimedia-capable on the iPhone and iPad but not on the Kindle itself – an irony which can hardly be allowed to continue, and which therefore doubtless presages the launch of a multimedia Kindle some time in the near future.

Of course, the story of multimedia innovation in literature goes back much further than Vooks and the iPad. The British writer Andy Campbell, for example, has been publishing his own new media fiction online for years – most recently on the Dreaming Methods website. Most of his work has been designed in Flash, which the iPad unfortunately does not support. He therefore finds himself in the one-step-forward-and-two-steps-back position where new media literature is finally starting to make some headway in the marketplace, but thanks to a whim of the Apple corporation his own work in the field, developed over more than a decade, been landed with a big disadvantage. Understandably, his feelings are mixed:

It does indeed seem like there is a shift going on with digital fiction, although there are still a large number of stumbling blocks from a development point of view… Whilst the potential of the iPhone and iPad is undoubtedly exciting, a lot of authors – including myself – do not work with Macs or have the programming experience required to produce Apple-happy content…. However that’s from the point of view of Apple dominating the market and forcing everyone to use their SDK, whilst in actual fact Android holds considerable promise… I wouldn’t say digital fiction is breaking through into the mainstream – although perhaps it depends what you mean by digital fiction… Whether anything has been produced that really takes reading as an experience to a new level, I’m not sure.

Since Flash has hitherto been one of the main tools used by new media writers and artists, many of them will now find themselves in the same predicament as Campbell – and many of them will doubtless be hoping, like him, that alternative platforms such as Android are going to make some headway in the coming months. But leaving the question of platforms on one side, another difficulty for existing new media writers seems to be that although publishers are suddenly discovering a new enthusiasm for the form, they have very little knowledge or understanding of the work which has already been done, and very few links with those who have been doing it. Nor is this entirely the publishers’ fault, because there seems to be a genuine cultural divide between those who work in the publishing industry and those who take an interest in new media literature. Emily Williams of Digital Book World alludes to this divide in her article about this year’s London Book Fair (“Old London vs. New Media”, April 2010):

In most [publishing] houses, the digital innovators are still operating on a parallel plane, touching on but not fully integrated into the publishers’ core business centers. This segregation is so complete that much of the digital crowd is liable to skip the traditional fairs altogether, gravitating instead to their own tech confabs (which are in turn often boycotted by, or unknown to, the bookish folk).

Michael Bhaskar, a publisher and one of the judges of the Poole Literary Festival’s New Media Writing Prize, makes a similar point in his blog:

There has been no real conversation between the two [publishers and new media writers]. Why? It seems like we should have hit the meeting point where there could and should be a productive alliance, when in fact the gulf seems as wide as ever… Publishers have to sell books – or something – to keep going… [whereas] much new media writing is not designed to be commercial, being associated with a more recondite and experimental mindset.

In other words, publishers and new media writers have failed to come together, not simply because publishers have been hoping for the digital revolution to go away, nor because new media writers have been go-it-alone experimentalists, but because culturally they have belonged to different worlds, moved in different circles and spoken different languages.

Even assuming that these difficulties can be overcome, it is open to doubt whether new media writers will necessarily want to throw themselves headlong into the commercial mainstream. Many of them, like Andy Campbell, have been going it alone for so long that the habit of independence may be difficult to shake. Undoubtedly a bit of money would be very welcome, but advice from marketing men about how to make their work more commercial might be less well-received. On the publishing side of the equasion, however, there are definite signs that things are starting to change. Experimentation was the buzzword of the 2010 London Book Fair:

The publishing industry must move at speed to adopt new business models and new ways of working if it is to seize the opportunities of the digital revolution, delegates were told at London Book Fair… Industry figures focused on the need to experiment and to get a real understanding of what consumers want from the new technologies in a fast-changing environment. (The Bookseller)

There are also signs that the influence of digital technology on writing now extends beyond the software-savvy fringe, and is starting to affect the ways in which less specialised writers create their work. One of the surprize best-sellers of last year was a book called Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion and Jewellery, by Leanne Shapton, which (as the title suggests) takes the form of an auction catalogue, selling off the belongings of a fictional couple. As befits an auction catalogue, the book consists of photographs of the articles for sale, accompanied by snippets of text –

Lot 1231: Two pairs of white shoes. Two pairs of white bucks. The label inside the men’s pair reads “Prada”, the women’s reads “Toast”. Sizes men’s 11, women’s 9. Well worn. $40-60.

The artefacts in the catalogue are arranged in chronological order, which makes it easier for them to tell the story of the couple’s love-affair; but despite this concession to linearity what is striking about the novel, to anyone who has had very much to do with new media literature, is how like a piece of new media literature it is. Experimental it may be as a novel in print, but as a piece of digital writing it would be fairly conventional, albeit unusually well-put-together. It was obviously composed as collection of objects and pictures as much as a a piece of written text; there is no conventional dialogue or storytelling; despite its chronological sequence there is a strong non-linear element to the book, a feeling that it is as much designed to be dipped and skimmed as to be read from one end to the other; it makes a knowing reference to Raymond Queneau, the Oulipo writer; and in many ways it would be more at home on the Web, where the pictures could be in full colour and zoomable at no extra expense.

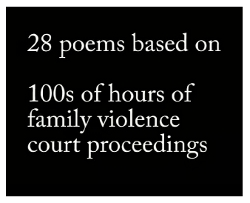

Another example of the influence of digital technology on “ordinary” literature comes from the small-scale end of the publishing industry – Martha Deed’s poetry chapbook The Lost Shoe, which was published earlier this year by Dan Waber at Naissance Chapbooks (about whom, more in a moment). The first point to note about this collection is that in order to publicise it Martha made a video, also called “The Lost Shoe” (http://www.sporkworld.org/Deed/lostshoe.mov), which deserves to be thought of as a companion-piece rather than a “trailer”. The poems in the collection are based on Martha’s experiences as a psychologist specialising in family law – more specifically, they deal with cases in which family members have done violence to each other, and some of them are harrowingly raw:

Upstairs, he tried twice to change his clothes

his fingers slippery with your blood…

You were looking at him

the last person you saw before your death

It bothered him, that lifeless stare,

so he stepped over your mother

your dying baby sister

and tried to close your eyes…

The video has the same combination of near-documentary authenticity and artistic control. It starts with a 911 telephone call from a man who has harmed his own children. There is a terrible moment when he is asked what has happened and he breaks into hysterical tears and says “They got stabbed”, as if somebody else might have done it. It ends with Martha reading aloud from one of her own poems, “Practice Tips”, which is based on the Center for Criminal Justice Advocacy‘s “Criminal Pre-Trial and Trial Practice”:

Play the tape 10 times at trial.

The jury will become accustomed to the carnage…

Obfuscate. Whine. Grandstand.

Fumble with your papers.

The fact that Martha feels equally at home working with both the written word and the camera, and therefore feels able to shoot her own video as a means of publicising her collection of poems, is an indication of the way in which digital technology is beginning to influence literary practice at grass-roots level. But the influence goes further. As well as conventional verse, her collection contains a number of visual poems – you could almost call them diagram poems – combining text with graphic design. “Jury Pool”, for example, shows a number of black stick-figures in and around the jury pool, labelled with reasons why they have been disqualified from the jury, or factors which will influence their outlook on the case: “Have to go back to school”, “Ate lunch with defendant’s mother”, “Crime victim”, “Don’t understand English”, and so forth. Including a diagram-poem such as this in a collection of poetry would not have been impossible before digital technology came along, but the fact that software packages such as Microsoft Word and Open Office Writer can handle images as easily as text, and make it simple to customise page-design without incurring any extra cost, means that poets now have an enormous range of experimental possibilities constantly at their fingertips.

Furthermore a lot of writers haven’t just moved beyond the pen or the portable typewriter to computers and word processing software; they have moved on to such things as blogs and web-pages, which have built-in multimedia capabilities. Sound-files and videos are rapidly becoming a normal part of the amateur writer’s working environment, and as a result the combination of text with other media is becoming a grassroots staple rather than a specialists-only field.

The Lost Shoeis published by Naissance Chapbooks, run by Dan Waber. A glance through Waber’s catalogue is enough to confirm the effect which digital technology is starting to have on poetic style. Amongst more formally conventional poetry he publishes, for example, Psychosis by Steve Giasson, which is based on comments collected by a YouTube posting of the shower scene from Psycho:

kthevsd Lame movies ? Kid I like all movies, old films, new films, etc. How is this classic lame ? Have you even ever watched it ? What would some 16 year old teenybopper know about cinema ? You probably have never even heard of Kurosawa and I bet you have never even seen a Daniel Day Lewis or Meryl Streep movie in your life. No wonder everyone laughs at your generations taste…

Or there is a collection by Jenny Hill called Regular Expressions: the Facebook status update poems –

Ron: I delivered a fucking BABY tonight! Yep, a fucking BABY!!!!!!!!! what did

u do today? Nursing school is AWESOME!!!!!!!

Someone asks if it was slimy, another wants

the placenta, most are stumped

at how to comment

on all your exclamation marks.

Then there is Watching the Windows Sleep by Tantra Bensko, which combines “fiction, poetry, and photographs”; or Open your I by endwar, which is “at times concrete, at times typoem, at times visual poem, at times conceptual poem, at times typewriter poem”. It is clear that the digital revolution has affected all of these collections in one way or another – either by making a wider range of experimental options available, or by providing them with their inspiration and subject-matter.

Of course, these are atypical exhibits, because Dan Waber, the publisher, is clearly interested in adventurous and experimental kinds of poetry. He also publishes a series called “This is Visual Poetry“, which now runs to about fifty full-colour booklets of visual poems, “answering the question [What is visual poetry?] one full-color chapbook at a time”, and answering it extremely variously. All the same, even allowing for Waber’s adventurous tastes, the fact that within a couple of years he has managed to put together fifty chapbooks of visual poetry, plus nineteen “conventional” poetry collections which often show clear signs of technological influence, is strongly suggestive of the directon in which things are moving.

Just as noteworthy is the business-model behind Waber’s publishing ventures. Basically, his operation relies on three key elements. The first is print-on-demand technology, which has almost completely done away with the printing expertise on which book production used to rely. These days, as long as writers can produce a competently-laid-out electronic original it can be turned into a book at the touch of a button. Colour reproduction is slightly more expensive than black-and-white, but not prohibitively so. Standards of reproduction are undoubtedly lower than they would be in the hands of a specialist printer, but most people never notice the difference. Self-publishing ventures such as Lulu (www.lulu.com) rely on this kind of print-on-demand process, and although Waber sends his electronic originals to the local print shop rather than using a completely automated online process, the technology is the same.

However, whereas the Lulu publishing process involves quite a bit of donkeywork (and usually a crash course in book-design and pagination) on the part of the author, the second key element of Waber’s publishing model is a drastically simplified and stringent set of layout criteria. Submissions to the visual poetry series must be “17 color images of visual poems of yours that are 600 pixels wide by 800 pixels tall”; and submissions to the Naissance chapbook series must be a maximum of 48 pages, in A4 portrait layout, with specified page-margins. Waber has designed a macro which takes Word files laid out according to these specifications and converts them instantaneously into print-ready book originals. This means that responsibility for the page layout is left squarely with the author – as Waber’s guidelines say, “all you need to do is make each page look how you want it to look… and we’ll convert it” – with the added effect that as long as authors stay within the guidelines, they are free to experiment as much as they like.

This combination of strict limitations and artistic freedom has undoubtedly helped to foster some of the adventurous design his chapbook series displays. At the same time, however, Waber has eliminated so much complexity from the publishing process that the third key element of the business model looks after itself: his costs (including time-costs) have come right down, to the point where he can show a modest profit on print-runs as low as ten units. All he has to do is decide whether he wants to publish something: if he does, he runs his macro, sends his print-ready file to the printer, and has ten copies of the chapbook in his hands within 24 hours. As he writes with understandable pride:

The beauty in all of this is no cash outlay. No huge print runs. No wondering if there’s grant money to support it, no worrying if it’ll actually sell enough to cover costs. It’s all profit after one copy sells… I am in a situation where because I make money off of every book I publish, all I need to do is find more books to publish. Because I de-complexified the process so completely.

Waber believes that his kind of venture represents the way forward for literary publishing in the era of digital technology, and he also believes that it is the kind of solution which can probably only come from outside the existing print industry, not from inside, because, as he puts it, “Big Publishing has a model that is blockbuster-based”. To explain this more fully, he cites an article by Clay Shirkey called “The Collapse of Complex Business Models“, which argues that big and complex businesses become unable to adapt to new circumstances, because their ideas about how they should operate become culturally embedded. If the new circumstances are sufficiently challenging then the only way forward will be for big organisations to collapse, and for new small ones, without the same culturally embedded assumptions, to take their place.

When ecosystems change and inflexible institutions collapse, their members disperse, abandoning old beliefs, trying new things, making their living in different ways than they used to… when the ecosystem stops rewarding complexity, it is the people who figure out how to work simply in the present, rather than the people who mastered the complexities of the past, who get to say what happens in the future.

This, argues Waber, is likely to be the ultimate effect of the digital revolution on the publishing industry; not simply dramatic changes in publishing formats and marketing methods, but a complete collapse of “Big Publishing”, and a multitude of small-scale, dynamic new ventures like his own, growing up out of the wreckage.

Clearly this is something that publishers themselves are worried about. As Michael Bhaskar writes in his blog for The Poole Literary Festival’s New Media Writing Prize,

On the writing side I often hear that people feel ignored by publishers.Essentially the world of commercial publishing is a closed shop unwilling to listen to the maverick, the outsider and the original, and will ultimately pay for this as audiences gravitate to newer and amorphous forms… This might be an argument for by-passing publishers or intermediaries altogether… [but] what I would like is mediation.

Clay Shirkey quotes the example of the “Charley bit my finger” video on YouTube to illustrate how production values have changed:

The most watched minute of video made in the last five years shows baby Charlie biting his brother’s finger… made by amateurs, in one take, with a lousy camera… Not one dime changed hands anywhere between creator, host, and viewers. A world where that is the kind of thing that just happens from time to time is a world where complexity is neither an absolute requirement nor an automatic advantage.

The “not one dime changed hands anywhere” line is perhaps a bit of an oversimplification. Wikipedia notes that “According to The Times, web experts believe the Davies-Carr family could earn £100,000 from ‘Charlie Bit My Finger’, mostly from advertisements shown during the video.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlie_Bit_My_Finger) But the Davies-Carrs didn’t make or post the video with the intention of becoming celebrities or making money. They posted it so that it could be viewed by the boys’ godfather. The success of the video, in other words, owes nothing to its production values or to any marketing strategy, and everything to the environment created by YouTube and its viewers.

An alternative to the Big Publishing model is already with us, and despite odd viral phenomena like “Charlie Bit My Finger”, it consists in the main of very large numbers of small-scale products reaching small audiences, rather than small numbers of very high-profile products reaching huge audiences. This alternative model is enabled by digital technology, and it replaces high production values and market-minded editorial controls with the principle that people’s desire to publish themselves and to look at each other’s efforts is itself a profit motor. No single book published by Lulu, for example, has to sell a lot of copies for Lulu itself to make a profit – it’s the volume which counts. The same is true of YouTube, and it’s also true, on a much smaller scale, of Dan Waber’s enterprise.

YouTube is now crawling with people hoping to become the next viral phenomenon – and there are also a number of talented individuals who have built up sizeable audiences on YouTube and who are making decent amounts of money out of those audiences – but the really big money is being made not by the people who contribute material, but by YouTube itself. The same is true of print-and-paper publishing via Lulu. The removal of editorial constraint has greatly freed up and democratised the creative side of the publishing process, but on the other hand, a system where most writers made relatively small amounts of money compared to publishers and agents is being increasingly shoved aside by a new system where most creators make no money at all, while the publishers do very nicely.

Add to this the fact that YouTube is now in the hands of Google – the same Google which has been “creating an impenetrable content monopoly” over digitised books through the Google Books programme – and the future of publishing starts to look less like an open field for small enterprises, created by the collapse of big corporations, and more like a battleground where a few monster Web 2 corporations – Amazon/Kindle, YouTube/Google and Apple – are carving up the territory as fast as they can, much as the major European countries carved up Africa during the nineteenth century.

What the future really holds for the publishing industry is probably a mixture of these two scenarios. It’s unlikely that conventional publishing is going to disappear any time soon, but in a shrinking market publishers are going to be more and more reluctant to publish untried material, more and more inclined to go with material which seems to tap into an already-established audience. The celebrity biography or autobiography; the book of the comedy series; the first novel by a TV personality; these are already familiar. The book version of a popular blog and the “global distribution” edition of something which has already sold very well via the Web are going to become increasingly familiar in the near future. Add to this books with associated websites, increasing emphasis on ebooks, and a cautious trial of ebooks with interactive elements, and you have a pretty good picture of how the conventional publishing industry is shaping up to deal with the digital revolution.

In the meantime, entrepreneurs like Dan Waber are taking fuller advantage of the new possiblities offered by digital technology, and perhaps planting the seeds for a whole new generation of publishing houses; while writers like Martha Deed and Leanne Shapton, under the influence of the digital revolution, are redefining literary genres.

But one consideration which should not be overlooked in all this is the importance of open standards. The digital revolution itself is predicated not only on technical advances – such as broadband, print-on-demand, digital video and multimedia handheld devices – but on the Web itself, and in particular on the fact that the Web is non-commercial and belongs to all its users. Material which appears on the Web doesn’t have to comply with a proprietary format laid down by any one corporation: it has to comply with standards laid down by the World Wide Web Consortium. It is this open structure which has enabled the Web to develop so rapidly and to serve as a framework within which so many enterprises have been able to flourish. For the field of publishing to flourish in the same way, open standards need to prevail here as well – open standards for ebooks, for example, so that standards-complaint work will be viewable on a whole range of different devices. Only under those circumstances can small enterprises and individual artists stand some kind of chance against the big corporations.

http://www.hyperex.co.uk/reviewdigitalpublishing.php

© Edward Picot, August 2010

© The Hyperliterature Exchange

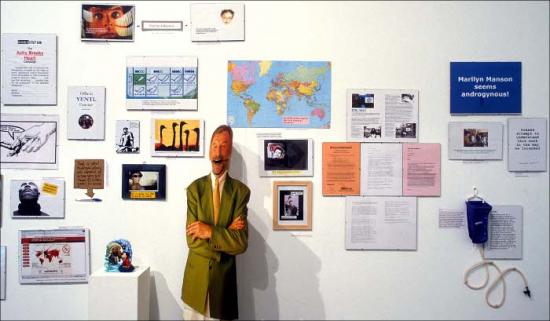

Above image taken by Scott Beale, Laughing Squid.

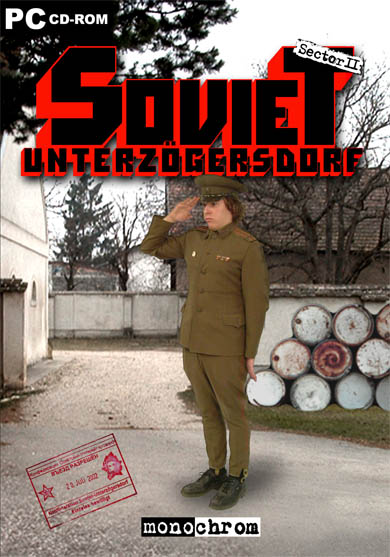

Marc Da Costa interviews the ever dynamic Johannes Grenzfurthner, founder of monochrom. This is the first of three interviews, where he talks about the project ‘Soviet Unterzoegersdorf’; the fake history of the “last existing appanage republic of the USSR”. Created to discuss topics such as the theoretical problems of historiography, the concept of the “socialist utopia” and the political struggles of postwar Europe. In March 2009 Monochrom presented ‘Soviet Unterzoegersdorf: Sector II’. The game features special guest appearances of Cory Doctorow, Bruce Sterling, Jello Biafra, Jason Scott, Bre Pettis and MC Frontalot.

Since 1993, the Monochrom members have devoted themselves to the grey zones where systems intersect: the art (market), politics, economics, pop, gaiety, vanity, good clean fanaticism, crisis, language, culture, self-content, identity, utopia, mania and despair. The technique underlying Monochrom’s work is that of being and working in the fields of Pop/avant-garde, theory/reflection, interventionism/politics, gaiety/lust/tragedy, (self-)configuration/mystification. The project Monochrom pushes into and beyond these fields is, ‘networking’ events, people, possibilities, material, impetus and identities.” (Zdenka Badovinac, Moderna Galerija Ljubljana)

Grenzfurthner has collaborated with groups such as ubermorgen, Billboard Liberation Front, Esel and Mego (label). Grenzfurthner writes for various online/print magazines and radio stations (e.g. ORF, Telepolis, Boing Boing). Grenzfurthner has served on a number of art juries (e.g. Steirischer Herbst, Graz). He holds a professorship for art theory and art practice at the University of Applied Sciences, Graz, Austria and is a lecturer at University of Arts and Industrial Design in Linz, Austria.

Recurring topics in Johannes Grenzfurthner’s artistic and textual work are: contemporary art, activism, performance, humour, philosophy, sex, communism, postmodernism, media theory, cultural studies, popular culture studies, science fiction, and the debate about copyright.

The ‘Soviet Unterzoegersdorf’, a game created by monochrom, is described as being at once the “last existing appendage republic of the USSR” and located inside the Republic of Austria. Could you speak a bit about the project and its background?

From a conceptual background we have to state that we have been occupied with the construction, analysis and reflection of alternative worlds for quite a long time. A lot of our projects are treating this field partly as a discussion with concepts deriving from popular culture, science and philosophy, and partly as a direct reference to science fiction and fantasy fan culture. We first created the fake history of the “last existing appendage republic of the USSR” in 2001 — ten years after the ‘mighty Soviet Union’ went into this nation-state-splitting-up-process and new countries emerged like Firefox pop-ups that you can’t manage to click away.

We wanted to discuss topics such as the problems of historiography, the concept of “utopia” and “socialist utopia” and the political struggles of postwar Europe in a playful, grotesque way. You have to bear in mind that the real village of Unterzoegersdorf was part of the Post WWII Soviet zone from 1945 until the foundation of the ‘neutral’ Republic of Austria in 1955. Reactionary Austrians talk about 1955 as the ‘real liberation’… and I have to mention that that’s rather typical: cheering when Hitler arrives and being proud members of the Third Reich, afterwards proclaiming that Austria was the first victim of Nazi Germany and complaining about the allied occupation forces — especially the Soviet.

We transformed the theoretical concept into an improvisational theatre/performance/live action role-playing game that lasted two days. That means we really organized bus tours to Unterzoegersdorf — a small village that really exists — and acted the setting; beginning with the harsh EU Schengen border control. Later, in 2004, we started to think about a possible sequel to the performance. We thought that the cultural format of the “adventure game” provided the perfect media platform to communicate and improve the idea.

We started to work in February 2004 and presented ‘Sector 1’ — the first part of the trilogy — in the form of an exhibition in Graz/Austria in August 2005. We released ‘Sector 2’ in 2009, featuring guest stars as Cory Doctorow, Jello Biafra or Bruce Sterling. As the game series uses a 3rd person perspective with photo backgrounds and pictures of real actors as sprites, it took us quite a while to digitize and image process all of the material. This technique was actually first used by Sierra On-Line during the early and mid-1990s — but we are quite proud that we managed to get the feeling of discovering an old computer game that never existed on your old 500 MB hard drive. One aspect of the game is playing with memories and the future of the past. The future is a kind of carrot, the sort tied just in front of the cartoon donkey’s nose so it goes to work, goes off to war, learns Javascript and knows which bits to laugh at in Woody Allen’s Sleeper. You can imagine.

At a HOPE conference a few years back I was interested to hear you talk about the framing of the project as somehow deeply connected with a certain understanding of historiography that you and the other members of monochrom share. Could you elaborate on this a bit?

Debates triggered by postmodern culture have directed our attention towards questions of representation and the relevance of “history” and stories — i.e. The challenging proclamation of a post-histoire, the realization of the impossibility of a meta-narrative of history; the clash between reality and sign systems, the difference between fact and fiction, the impossibility of neutral contemplation or witnessing as well as the positioning of subjective awareness within such representations, etc. All these forms of representation have been playing a central part in the development of national, ethnic and tribal identities since WWII. And (as a by-product of military technology) computer game development is hardly aware of these discourses.

We wanted to combine (retro)gaming and (retro)politics and (crypto)humor to delve into this ongoing discourse. We wanted to harvest the wonderful aesthetic and historic qualities of adventure gaming. It is a commemoration and resurrection, and one more reminder that contemporary gaming (in its radical business-driven state-of-the-artness) should not dare to forget the (un)dead media of the past — or they will haunt them.

If you compare the status of the adventure game in the context of the economic growth of the computer game industry you could state that it is gone. Less than 1% of all computer games written are adventure games. Adventure games are nearly extinct… but only nearly. If media and media applications make it past their Golden Vaporware stage, they usually expand like giant fungi and then shrink back to some protective niche. They just all jostle around seeking a more perfect app.

For many people in the Soviet Unterzoegersdorf team, adventure games are part of their media socialization. For the computer industry it is one of the most successful gaming formats of the past. And for the feminist movement it is proof that a woman — I’m talking about Sierra On-Line’s Roberta Williams — was able to shape the form of a whole industry totally dominated by men.