3 October 2019 – 5 January 2020, Daily. Free Entry

The roar of an airplane is a familiar sound for many parts of west London, home to one of the busiest airports in the world and the subject of a new exhibition, Air Matters at Watermans Arts Centre in Brentford, just a few miles away from Heathrow.

Echoing the experience of hearing an aircraft in action, sound itself plays an integral part in the show and leads with The Substitute (2019) by Hermione Spriggs and Laura Cooper. Through overhead speakers outside the main entrance, visitors are greeted by an authoritative voice musing on the fate of local flocks in an airspace strictly controlled by humans and their contraptions, intermittently reciting names of affected birds like a tribute, and ultimately urging listeners to “work with nature” which sets a critical tone.

The audio installation is reminiscent of public announcements at airports, a strategy that continues into the foyer with Frequency (2019) by Louise K Wilson. It features intimate anecdotes of air travel through resonance devices on a skylight roof where planes might fly by at any moment. Speaking softly akin to ASMR, one person wonders about the destinations of travellers, while another recalls vivid memories of flights that seem traumatic, bouncing back and forth between excitement and anxiety.

The theme reaches its crescendo inside the gallery, with a mixture of ambient sounds reverberating across the space from Ascending Composition I (For Planes) (2019) by Kate Carr, an atmospheric concoction of incidental noises recorded around Heathrow including birds, markets, and trains on tracks. With pocket-sized media players attached to deconstructed speakers on strings of fabric, the installation documents an intervention that already took place when the work itself flew up on balloons blasting whispers from the ground, a small but meaningful gesture challenging the sonic waves of jumbo jets that dominate the surrounding sky and soundscape.

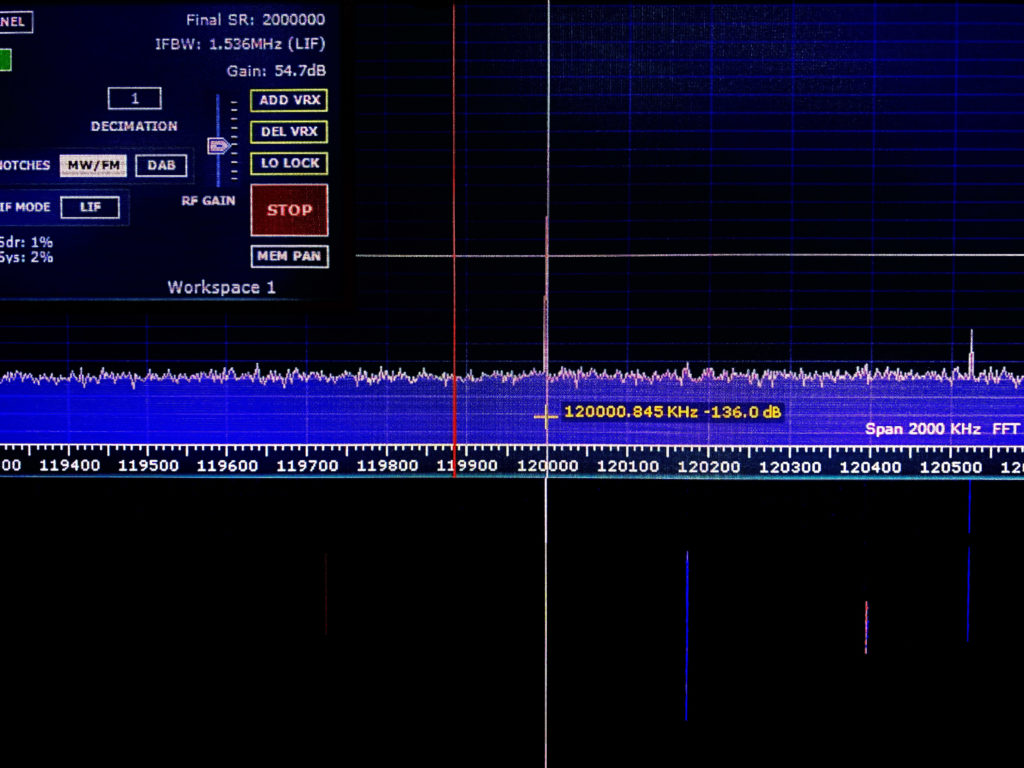

This act of defiance flows into Skyport (2019) by Magz Hall, a mixed media installation with a set of frequency scanners emitting an unsettling static. The title refers to a pirate radio station based along a Heathrow flightpath in the 1970s, illustrated with archival images and texts from an attempt to reclaim airwaves colonised by traffic control and engine noise. The work emulates this spirit with an LCD screen broadcasting airport channels as visual wavelengths, the contents of which are protected as classified information in UK law, consequently questioning ownership, access, and authority over radio frequencies.

The symphony of sounds become unavoidable throughout, and there is a possibility that it might grow vexing for some, perhaps more so for the people that work here who may not have a choice but to hear it again and again. Yet, as irksome as that might be, it is a crucial part of what makes this show effective. The audible pieces collectively transform the spaces into simulations of airport lounges and peripheral towns, simultaneously mimicking and counteracting oppressive noises from airplanes and terminals that have become inevitable in contemporary life, irrespective of its value and/or harm.

Beyond aural tendencies, the exhibition reaches further by considering scale and movement. The sheer volume of Capsule (2019) by Nick Ferguson is an imposing presence in the gallery with a wooden sculpture modelled after the wheel bay of a Boeing 777, floating a few inches off the ground and hovering over visitors. Shown alongside printed images of microscopic substances found in a real plane, it orchestrates a juxtaposition between the enormity of a flying machine and the imperceptible residue it accumulates, revealing traces from the many places it has been including sand, spores, and bacteria.

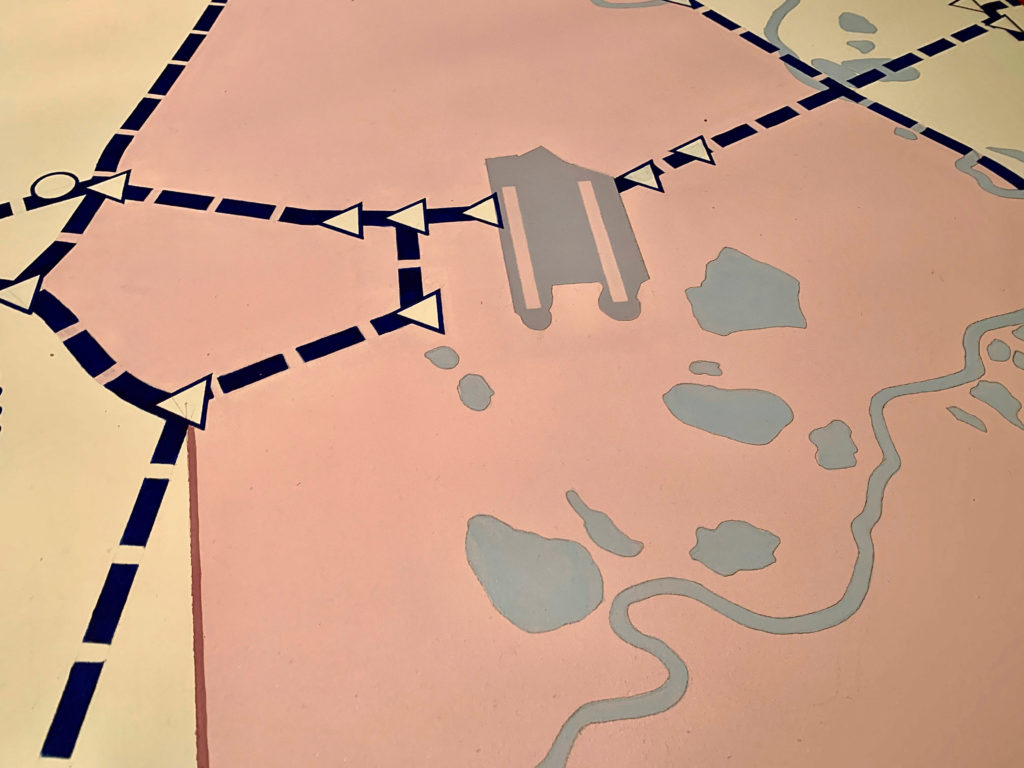

A map nearby, Heathrow (Volumetric Airspace Structures) (2019) by Matthew Flintham, takes the viewer back to west London with a bird’s eye view of the airport complex. Presented on a table that might be used for urban planning, military operation, or board games, it illustrates the topography of the area highlighting a vast infrastructure beneath large sections of controlled airspace, seemingly encroaching on everything else which becomes almost invisible or insignificant.

Navigating the show functions as an exercise of remembrance in many ways, bringing to mind a number of issues that have been at the forefront of public discourse in recent years: from the role of aviation on climate change, to its impact on local communities and ecosystems around airports. And it comes, as if on cue, at a period of heightened environmental concern, propelled most prominently by the Extinction Rebellion movement and climate activist Greta Thunberg, ringing the alarm on the perils of flying.

The controversial Heathrow Airport Expansion also comes through in this context, caught between government plans for future economic growth, and the ongoing resistance from neighbouring residents with campaigns like Stop Heathrow Expansion, No Third Runway Coalition, and Heathrow Association for the Control of Aircraft Noise.

It conjures up conflicting perspectives that unpack a classic dilemma for a society in flux. On one hand, the flight industry is evidently harmful because of its pollution to the planet and the unfair toll on local hosts. Yet, on the other, it is part of a system that facilitates international trade, freedom of movement, and cultural exchanges, each one increasingly more accessible to broader people beyond a privileged few who will always have it. And while it has serious problems that must be addressed, some of which are rightly pointed out here, a world without it entirely is at risk of descent into tribalism and isolationism.

With so much at stake at this particular time and place, the exhibition feels important for its worthwhile attempt in raising these pertinent questions through art, successfully using Heathrow as a case study for matters that undoubtedly have wider implications.

Like the rumble of a plane and many works in this show, the politics of flying will become inescapable as air travel is projected to almost double in size by 2036, despite recent backlash from flight shaming, the rise of staycation, and a spotlight on frequent flyers. The solutions to its unintended consequences are not as straightforward as it might seem, and will likely require a nuanced approach combining systemic changes, paradigm shifts, technological developments, and personal adjustments, all of which cannot come soon enough.

Air Matters: Learning From Heathrow is at Watermans Arts Centre until 5 January 2020. Curated by Nicholas Ferguson in collaboration with Klio Krajewska. Supported by Arts Council England, Forma, London Borough of Hounslow, Kingston School of Art, and Richmond University.

Featured main image: Kate Carr. Image 11. NF. Ascending Composition 1 (For planes). Mixed media, 2019. Included in Air Matters: Learning from Heathrow. 3 October – 5 January 2019.

“It is highly unlikely that we, who can know, determine, and define the natural essences of all things surrounding us, which we are not, should ever be able to do the same for ourselves – this would be like jumping over our own shadows.” – Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

One & Other, part of the Zabludowicz Collection’s annual Testing Ground Project, is a curatorial collaboration between MA Curating students from Chelsea College of Arts and CASS, London Metropolitan University. The show holds together works by Ed Atkins, David Blandy, Cécile B. Evans, Leo Gabin, Isa Genzken, Rashid Johnson, Tim Noble, Sue Webster, Ferhat Ozgur, Jon Rafman, Ugo Rondinone, Amalia Ulman, Ulla Von Brandenburg and Gillian Wearing.

The exhibition threads the simultaneously disturbing yet beautiful dualities between the simulated daily persona humans perform and, as Atkins’ work states, ‘actual’ human presence – the distinction between real and the Other.

Walking into the main area of the late 19th century former Methodist Chapel, Atkins’ work echoes through the two-storey building in an authoritative manner, “read my teeth, read my lips, listen, listen, you don’t know how to listen”.

Situated on the ground floor of the space, No one is more WORK than me (2014) appears to be a lower grade CGI avatar of Dave, a persona from Atkins’ Ribbons. I will just call him Dave. Dave is glitchy, at times not synced. His desire to bring himself into the perceived physicality is overwhelming as he elaborates on causal harm features making himself more human, ‘it’s blood, it’s blood, there’s a bruise’. All the works within the space, share the same space and thus are always accompanied by the backdrop of Atkins’ voice, repetitively stating ‘this is my actual head’ and describing the features on the figure’s face. Dave’s comments about his ‘actual’ body features shape the ambience and undertones of the show.

Shown on a flat screen placed on the floor, Dave commands the space to his will as the only video work not bearing headphones. Dave sings for us on multiple occasions, specifically performing Bryan Adam’s ‘Everything I Do (I Do It for You)’. At times he becomes almost irrationally frustrated with himself and the audience, tells us to do him ‘a favour’ and ‘fuck off’. His performance – and frustration – are immersive and quite literally frame the entire show around the work’s presence. Cécile B. Evans’ work positioned directly opposite it, corresponds with teeth, although harmoniously to the corporeal visuals provided by Atkins’ work.

Evans, now exhibiting at the Tate Liverpool, has been making outstanding work since I first came across Hyperlinks, or it didn’t happen (2014) at Seventeen Gallery in London. In One & Other, her video, The Brightness (2013), involves the visual three-dimensional participation of the audience as the invigilators provide 3D-glasses. She states ‘I am here because I am plastic’ and ‘I was real then’, whilst a CGI render of pirouetting teeth is shown, dislocated from their place of origin, the mouth.

The teeth, traditionally a sign interpreted from dreams as a symbol of anxiety, are animated, dancing and may be symbolising the unease experienced when becoming something outside of what you are. Evans’ work is placed within close proximity to Atkins’ work, adjusting for a very comfortable relational approach to both pieces in conversation with each other as motifs of personifying the unanimated, the plastic.

Sleeping Mask (2004) is a mask of a human face made out of painted wax. Playing with notions of human disguised as human, Wearing creates a re-enactment of one of the most human physical properties, the face. Sleeping Mask was placed on a plinth, on a slightly elevated podium, with a singular spotlight shining on it like the Genie Lamp in the Cave of Wonders, thus proving that particular notion to be very effective.

Less effective, and regrettably so, one of the weaker curatorial links to the show, was the inclusion of Amalia Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections – Do You Follow? (2014). As a scripted online-performance viable and lived through her Instagram account, Ulman appears to be critiquing the vanity of self-indulgent approval on social media. Through creating the persona of an overactive digital self, Ulman’s work comes as no surprise when taking into consideration the wider context of the conceptualisation of One & Other. Having been featured in The Telegraph this time last year, she seems to have grabbed the attention of a more public young audience, themselves feverishly present on social media. Whilst her inclusion is not controversial at all, it more so had the teetering effect of ‘oh, it’s that work by Amalia Ulman’. The decision to include her in the show might be interpreted as making a statement – audience participation within this critique becomes redundant as it is vocalised through the very tool she is critiquing. Nonetheless, the surprising addition of Sue Webster and Tim Noble’s work, Ghastly Arrangements (2002), made up for the aforementioned curatorial paradox.

Placed in a room of their own, the work captivates all attention in the darkness. Ghastly Arrangements is an arrangement of silk and plastic flowers in a ceramic vase with a single spotlight projecting its shadow onto the wall. The work addresses the concept of human duality without using humans as a visual medium, perhaps even addressing it more appropriately because it doesn’t involve humans- it involves shadows. The Other in One & Other, is an entity by which can be projected onto, containing duality. Such is Ghastly Arrangements, as the Other assumes a signifier through the shadow as the self. An object can thus be a more powerful vehicle for thought than representation itself – another point made with Jon Rafman’s choice regarding plinths.

A friend of mine once said that a good plinth signifies art with value, making it the ultimate art object. Rafman’s New Age Demanded (2014) is a series of digital sculptures, scattered on tall mirror coated plinths with self-assured confidence on the wooden stage stairs in the upstairs area. Faceless representations of humans are created through quite uncanny looking textured materiality; smooth marble, dripping resin, copper patina and rough concrete. The non-faces are unidentifiable and the absence of definite characteristics moulds an audience-subjective projection of the Other self. The mirror plinth adds to the dimension of projecting oneself, the performative experience and known duality of the self in contemporary society begging the question of, ‘How many people do we exist as?’

Overall, within such an overwhelmingly impressive structure housing the Zabludowicz Collection, a near-perfect group show can prove very challenging to execute. The architecture of the space, its high ceilings, stage and upper balcony, may interfere with the presentation of the art. In One & Other’s case, it felt as though there was too much going on, conceptually but more importantly spatially. Rafman’s immense installation would have been better suited as an isolated entity in the balcony upstairs, whilst the works of Atkins, Evans, Wearing, Webster and Noble could have also stood their own ground conceptually without any further additions. One & Other felt like it could have done with constraining itself to only one type of self-identifying duality, instead of attempting to assess multiple, and although I love the work of Rashid Johnson, it felt slightly out of place within the space; perhaps less is more.

Whilst this piece of writing is only comprised of personal highlights and observations, One & Other is a show not to be missed, and to inspire fellow young and aspiring curators.In the curatorial team for One & Other were Caterina Avataneo, Ryan Blakeley, Nadine Cordial Settele, Sofía Corrales Akerman, Gaia Giacomelli and Angela Pippo.

On until the 26th of February 2017.

All images by Tim Bowditch, courtesy of the Zabludovicz Collection.

At first glance networks and the practice of drawing would seem to be worlds apart. However, the diagram, originally a hand-drawn symbolic form, has long been employed by science as a means of visualising and explaining concepts. Perhaps the most important of these concepts is that of relationships visualised as circles and lines that represent nodes and links or effectively what is related. As such networks, that is groupings of relationships, have come to be visualised through the use of the same styles and iconography employed in diagrams. For artists to reclaim the diagram as a part of their own practice and thereby adopt the practice of visualising networks developed within science sees the practice of creating diagrams in a sense come full circle. Artists have time and time again drawn diagrams and networks that explore relationships. For example: Josef Beuys famously used blackboard diagrams as part of his teaching performances concerning art and politics; Stephen Willats has since the 1960s developed drawn diagrammatic works that explore his socially formed practice; Mark Lombardi drew societies’ networks of power relations throughout the 1990s; Torgeir Husevaag has since the late 1990s drawn diagrams of a number of networks within which he participated while Emma McNally draws diagrammatic networks “bringing different spaces into relation [such as] the virtual world, the networked world and the supposedly real world” (Hayward, 2014).

The work of Suzanne Treister resides within this category of artist’s drawing, and in this instance also painting, networks. With a background in painting Treister works across video, the internet, interactive technologies, photography, drawing and watercolour painting (Treister, n.d.). Her work employs “eccentric narratives and unconventional bodies of research to reveal structures that bind power, identity and knowledge” (ibid) within contemporary contexts. As a result of this process of revealing structures, essentially the relationships within the subject matter she addresses and the resulting networks they form, her practice has since the 1990s been closely allied with art that employs or explores technology. She has been repeatedly included in exhibitions and publications that link her work with networks, cybernetics, new media and most recently Post-Internet Art (Flanagan and Booth, 2002; Pickering, 2012; Larsen, 2014; Warde-Aldam, 2014).

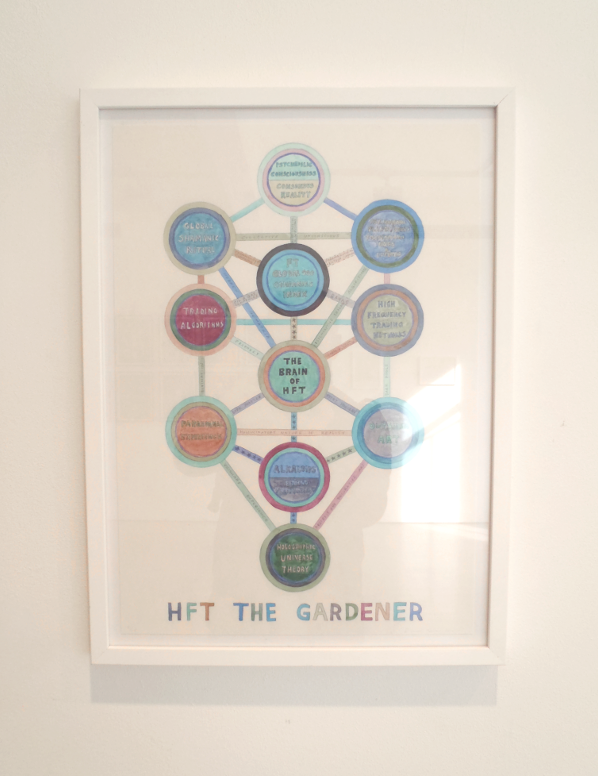

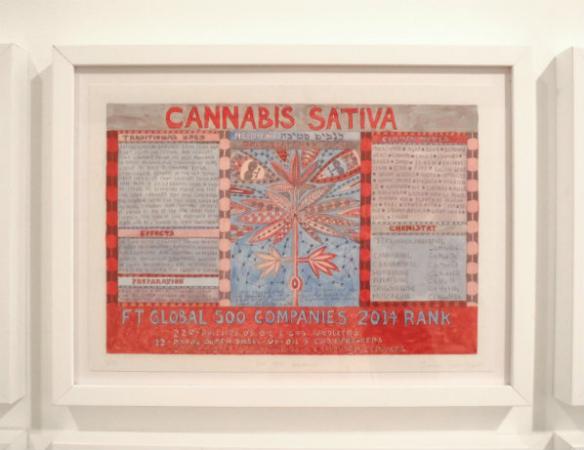

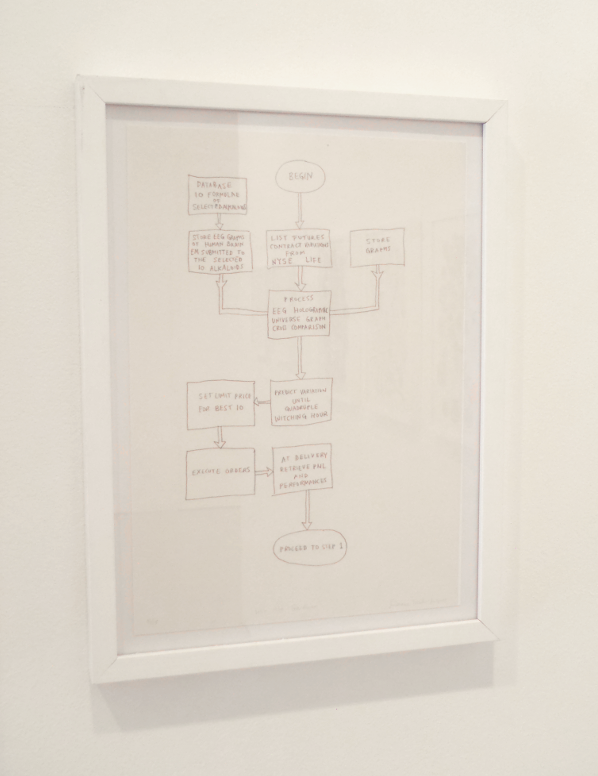

HFT the Gardener (2014-15), a recent solo exhibition by Treister at Annely Juda Fine Art in London, is a body of artworks consisting of drawings, paintings, photographs and digital prints supposedly created by a fictional character and a documentary video about the same character. The character, Hillel Fischer Traumberg, is an algorithmic high-frequency trader (HFT) within the London Stock Exchange. After an optically induced semi-hallucinogenic state, Traumberg experiments with psychoactive drugs in order to recreate and further the experience (Treister, 2015). Along the way Traumberg becomes fascinated with botany, experiments with the molecular formulae of drugs as trading algorithms, makes links between the numerological equivalents of plants’ botanical names and the FT Global 500 index, visually documenting all of his research and ultimately becoming an ‘outsider’ artist (ibid). In the process Traumberg transitions from an insider of one network, a trader within the stock exchange, to that of an outsider in another, the contemporary art world.

This juxtaposition of opposites is repeated throughout the exhibition. For example, the drawings and paintings of HFT the Gardener employ illustrations of networks containing nodes and links. These illustrate a number of different sets of relationships that are established by the artist. These include: that of the central character to his concepts, research and environment; the locations where drugs were taken; states of consciousness; the components of an algorithm; different companies within a sector and different aspects of the universe including life and art. Additionally a variety of diagrammatic forms are co-opted in the creation of the drawings and paintings including the Judaic Kabbalah Tree of Life, radial diagrams, flowcharts similar to those used in software design and reference is made to a number of other abstracted forms including star charts, snow crystals, fractals and paisley design. Through both form and subject matter the illustrations of networks and the diagrams gather together combinations of opposites. There is of course the use of what can be considered traditional media to illustrate new media forms, however among others there are also the opposites of painting and software, science and art, corporate and counter-culture, belief and fact, fiction and reality.

To coincide with the creation of the artwork a book of the same name has been published. In the foreword Erik Davis states that there is an “initial shock of Treister’s juxtaposition of esoterica and the financial sector” (2016). The same could be said of the numerous other juxtapositions that occur within HFT the Gardener. However, are Treister’s, or is it Traumberg’s, combinations really contrasts that shock? Treister does more than simply juxtapose opposites. The artist effectively synthesises them into a whole that is indicative of our networked era where individuals routinely select, cut, paste and combine combinations ad-hoc to suit a moment or context. HFT the Gardener is an artwork that could only be created in this era of networks and as such it cannot be considered shocking or out of context with the eclectic recombinatory society that surrounds it.

Not only are drawn diagrams and networks employed extensively throughout the exhibition in a number of ways but a network-like structure is also employed to arrange the artworks within the space of the gallery. Initially on entering the gallery space it seems as if artworks are arranged in no particular order. However it gradually becomes clear that this arrangement is purposefully obliging the visitor to enter into and move through the space as if it were a network; that is entering at any point and navigated in any order. While some series of artworks within HFT the Gardener, such as the Botanical prints, maintain an order to illustrate the ranking of companies employed in their creation, the majority of artworks are experienced out of the order they have been created and the documentary video about Traumberg, presumably from Treister’s perspective, is encountered at the midpoint of the exhibition. As such the artworks are presented as if they are interconnected nodes in a network.

As a result of the diagrams, illustrations of networks, juxtaposed combinations of subject matter and a network-like structure in arranging the artworks within the exhibition Treister successfully manages to make one last combination of opposites, that of non-linearity of experience and linearity of narrative. In doing so the visitor experiences the juxtapositions, combinations and resulting networks formed by Traumberg’s hallucinatory non-linear associations and yet manages to steadily interpret the detailed narrative carefully constructed by the artist. It is in this last combination where the strength of Treister’s exhibition lies as it not only reflects society at large but also suggests that art is and perhaps always has been, a non-linear networked experience that is only now coming into its own.

An exhibition catalogue of HFT The Gardener is available through ISSUU (https://issuu.com/annelyjuda/docs/treister_cat) and a fully illustrated book of the same name is available from Black Dog Publishing, London.

HFT The Gardener will continue to tour throughout 2017 at the following venues. Please see the artist’s website for exhibition updates.

22/10/2016 – 05/03/2017

Selected works from HFT The Gardener exhibited in The World Without Us

Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV),

Dortmund, Germany.

07/01/2017 – 18/02/2017

HFT The Gardener diagrams exhibited in Underlying system is not known

Western Exhibitions, Chicago, USA.

03/02/2017 – 05/03/2017

Selected works from HFT The Gardener exhibited in Alien Ecologies

Transmediale 2017

Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany.

Since the establishment of the World Wide Web, questions have proliferated around the possibilities, value and collectability of its associated contemporary art forms.

The web provides a single site for the creation (and sometimes co-creation), distribution, review and remix of an art form that takes as its medium: code, images, text, video, music and social relations. Historically, the value of an artwork resided in its uniqueness. Now artists, audiences, curators and collectors grapple with an infinitely replicable and distributable art form. This panel discusses an electrifying cluster of controversies: the subversive intentions and emancipatory motivations of many media artists; the needs and concerns of public art collectors and conservators; the opportunities for private collectors and the interests of high art market speculation.

This panel is chaired by Ruth Catlow, artist, co-founder and co-director Furtherfield, established in 1997 for art, technology and social change.

Steve Fletcher – Co-founder of Carroll / Fletcher, a recently established commercial gallery specialising in contemporary socio-political, cultural, scientific and technological themes

Lindsay Taylor – Salford University Art Curator who established the first UK public digital arts collection at the Harris Museum and Art Gallery

Please visit this page to register for this talk.

1) purified social process. Screenshot from VisitorsStudio, by Furtherfield 2011

2) The Lover by James Coupe. Surveillance video installation commissioned by Harris Museum, 2011

Contact: gabrielle@andfestival.org.uk

Hashtag: #6pmuk

Participants: TBC

VISITING INFORMATION

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

6PM YLT is a networked, distributed, one night contemporary art event, which takes place simultaneously in different locations, coordinated from one central venue, and documented online via a web application.

Furtherfield is hosting the first UK event, chosen for its history of critical engagement with networked culture.

At 5.30 pm, Domenico Quaranta and Fabio Paris from Link Art Center will talk through their ambitions and inspiration for the project. For the duration of the event, participating venues and their audiences across the UK will be testing the platform by sharing documentation images and videos of their events under the same hashtag, #6pmuk. The audience at Furtherfield will be able to enjoy the live feed from all the locations involved, and to discuss the project with us.

Artists, technologists, network thinkers and makers are invited to join us to learn more about the conceptual framework for 6PM YLT and talk through how it can evolve, in anticipation of its European launch in July. Food and drinks will be available!

6PMYLT is a format conceived by the Link Art Center and developed in collaboration with Abandon Normal Devices (AND) and Gummy Industries. On 22 July 6 PM YOUR LOCAL TIME launches across Europe.

6 PM YOUR LOCAL TIME (6PM YLT) is a networked, distributed, one night contemporary art event taking place simultaneously in different locations, coordinated from one central venue and documented online via a web application. The locations (institutions, non-profit spaces, commercial galleries, artist’s studios) will address their local audience and, through the dedicated web platform, a global audience. While visiting your local 6PM YLT event(s) will allow you to experience a single portion first hand, the only way to get the whole picture will be to access its online documentation: all exhibits will be documented and shared in real time by organizers and audience on the dedicated web platform, thanks to a web application aggregating content from different social platforms.

The lead partner will coordinate the event from one central venue, and will put on display the event itself, screening the live feed from all the locations involved, and eventually making additional documentation available in different ways, ie. arranging video conferences with specific venues, or printing out images in real time and displaying them as a wall installation.

After the launch event, 6PMYLT will become an open format available for anyone to utilise. The lead partners will maintain the platform and support the coordination of events all around the world.

Today, art is mostly experienced through its documentation. Even if globalization made it easier and cheaper to organize exhibitions, ship artworks, invite artists and move audiences to any part of the world, the excess of cultural activity all around the world makes it impossible to be everywhere at the same time. Bits are still faster and cheaper than atoms, and we can enjoy them more comfortably on different devices. The border between first hand and second hand experience, reality and media documentation becomes increasingly blurred, with a profound impact on the way art is produced and documented.

Almost every art-addict is now using social networks like Instagram, Twitter and Facebook to take photographs during art exhibitions and to share them with their contacts. The pictures already have some meta-data that we could use to trace them and to collect them: #hashtags, captions, geographical data, publishing date. By suggesting the use of a given #hashtag to all the organizers and audience participants, we can collect and show all this documentation on a dedicated web platform. Our software will automatically collect all the pictures, tweets, and public Facebook produced about the 6PM YLT event, and will show them in a single gallery.

6PMYLT is a format conceived by the Link Art Center and developed in collaboration with Abandon Normal Devices (AND) and Gummy Industries.

The Link Center for the Arts of the Information Age (Link Art Center) is a no-profit organization promoting artistic research with new technologies and critical reflections on the core issues of the information age: it organizes exhibitions, events, conferences and workshops, publishes books, forges partnerships with private and institutional partners and networks with similar organizations worldwide. More info: www.linkartcenter.eu

Abandon Normal Devices (AND) presents world-class artists at the frontiers of art, digital culture and new cinema. A UK based organisation it is a catalyst for new approaches to art-making and digital invention, commissioning public realm works, exhibitions, research projects and a roaming biennial festival. AND has commissioned work from Carolee Schneeman, Krystoph Wodischko, Gillian Wearing, Phil Collins, Rafael Lozano Hemmer and the Yes Men (to name but a few). More info: www.andfestival.org.uk/

Gummy Industries is an online communication and marketing agency based in Brescia, Italy. Their work ranges from consultancy to design and (web) development. They usually work with medium business and large companies, with a strong focus on the fashion industry. More info: http://gummyindustries.com/

Furtherfield was founded by artists Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett in 1997 and is been sustained by the work of its community; specialist and amateur artists, activists, thinkers, and technologists, who, together cultivate open, critical contexts for making and thinking. Furtherfield is now a dynamic, creative and social nerve centre where upwards of 26,000 contributors worldwide have built a visionary culture around co-creation – swapping and sharing code, music, images, video and ideas. More info: www.furtherfield.org.

Concept: Fabio Paris

Production: Link Art Center, Brescia, IT

Co-production: Abandon Normal Devices, Manchester, UK

Website and software development: Gummy Industries, Brescia, IT

Funded by: Creative Europe; Art Council England

6PM YOUR LOCAL TIME is realized in the framework of Masters & Servers, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Abandon Normal Devices (UK), Link Art Center (IT) and d-i-n-a / The Influencers (ES) that was recently awarded with a Creative Europe 2014 – 2020 grant. For 24 months from now, Masters & Servers will explore networked culture in the post-digital age.

Featured image: A live portrait of Tim Berners-Lee (an early warning system). Thomson and Craighead. March 2012.

Flat Earth was published to accompany two solo exhibitions. The first, Not even the sky at MEWO Kunsthalle, Memmingen, Germany from 26 October 2013 – 6 January 2014 and the second Maps DNA and Spam at Dundee Contemporary Arts, Scotland from 18 January – 16 March 2014. The book contains a foreword by Axel Lapp, essays by Dundee Fellow Sarah Cook and DCA Director Clive Gillman as well as an interview with the artists by Steve Rushton.

On the whole, the mainstream art world has failed to ‘convincingly’ adapt to (new) media art and similar contemporary art practices using networks and technology. Thomson & Craighead have overcome this impasse and this is one of a few reasons why they’re so interesting to look at as contemporary artists. The book, Flat Earth does not propose to cover all of their art and this review does not propose to cover all that it is featured in it. The review features Flat Earth Trilogy, The End, October and TRIGGER HAPPY (not in the book).

“Their work provides us with a new perception, through

a completely unexpected multi-focal perspective. They reveal

the wide ramifications of systems of information exchange and

provide us with an insight into the resulting infrastructure of

our own thinking.” [1] (Alex Lapp 2013)

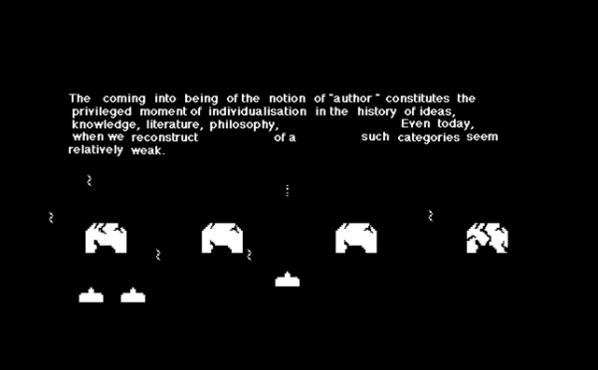

TRIGGER HAPPY: Shooting The Messenger.

Although TRIGGER HAPPY (1998), is not featured in the publication it provides a useful introduction to some of the ideas and conceptual approaches present in Thomson & Craighead’s later artworks. I first experienced the work online, but it’s also a gallery installation that takes the form of an early shoot-em-up arcade game, Space Invaders. This work reflects the sly and cheeky side of Thomson & Craighead and tells us how humorous they can be in their art. TRIGGER HAPPY is philosophical and playful. It asks the player to shoot down the text of Michel Foucault’s essay What Is an Author? published in 1969. [2]

Foucault said the depiction of knowledge is a production and truth is produced, and it is always a reconstructed falsification. In a way TRIGGER HAPPY gives us a chance to shoot at Foucault, who in this respect is the annoying messenger. At gut-level, this art object recognises that on the whole we prefer to shoot at things or play games, than to deal with the complex and pressing questions of our time. Even if the gamer does manage to destroy Foucault’s text, this action prompts an existential enactment of doubt and induces a more vulnerable state of interpassivity. This relates to the illusion of agency when playing games, using corporate online platforms like Facebook and other experiences involving interaction with media, and it can also be extended to life situations. Slavoj Žižek proposes that interpassivity is the opposite of interaction and says “that with interactivity a false activity occurs: ‘you think you are active, while your true position, as it is embodied in the fetish, is passive’. Žižek refers to the Marxist notion of commodity-fetishism to imply that social relations are increasingly reduced to objects (Žižek, 1998).” [3]

We can almost hear the catchphrases “it’s only a movie” or “it’s only a game” as we are compelled to shoot at rather than attend to the messages that may serve to enlighten us and free us from our societal conditioning.

Flat Earth Trilogy: A networked society’s gaze at its mediated self.

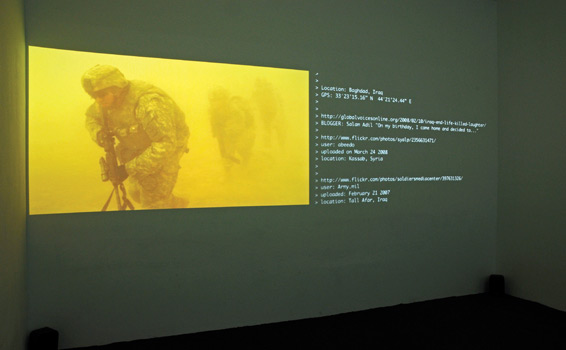

The Flat Earth Trilogy is a series of documentary artworks each made entirely from information found on the World Wide Web; with fragments collected from people’s blogs, This covers a six-year period beginning with Flat Earth (2007) A short film about War (2009/2010) and then ends with Belief (2012).

Commenting on A Short Film About War, on their website, Thomson & Craighead write “In ten minutes this two screen gallery installation takes viewers around the world to a variety of war zones as seen through the collective eyes of the online photo sharing community Flickr, and as witnessed by a variety of existing military and civilian bloggers.” [4]

In the book Flat Earth Steve Rushton discusses with Thomson & Craighead why he feels A short film about War works for him best. He says, “It seems to make a claim on truth – which is the traditional claim of the documentary in particular and photography in general – whilst at the same time it shows us that truth is constructed.” [5] (Rushton 2013)

These works challenge our notion of what a documentary is, what and who the author is, and leaves us with the question, what does this mean for the wider society? This brings us back to Foucault’s ideas on the production of truth and its falsification. Tom Snow writes “In the essayistic act of image compilation then, the piecing together of filmic clips and stills distorts the dividing line between fiction and fact, and reimagines the enigmatic relations between photographic mediums and the condition of representation.” [6] (Snow 2009)

Flat Earth, A short film about War, and Belief all relate to topics concerning human values, conflicts, militarism and everyday societal struggles. “Machines,” wrote Gilles Deleuze in his examination of Foucault’s thought, “are always social before being technical. Or, rather, there is a human technology before which exists before a material technology.” [7] (Berger 2014) And so the technologies we produce are another materialization of the continuing human story.

Millions of people, en-masse, are uploading their personal data (different indications of their states of being) to a collective assemblage. Alex Galloway says that in order to get a better understanding of what networks are we must put aside the idea that networks are a metaphor. He proposes networks as part of a materialized and materializing media. He views this as an important step toward understanding the “power relationships in control societies.” [8] (Galloway 2004)

“It is a set of technical procedures for defining, managing, modulating, and distributing information throughout a flexible yet robust delivery infrastructure.” And “More than that, this infrastructure and set of procedures grows out of U.S. government and military interests in developing high-technology communications capabilities (from ARPA to DARPA to dot-coms).” [9] (Ibid 2004) Galloway’s distinction helps us to re-evaluate what he sees as distracting tropes and uncritical interpretations of the Internet, the World Wide Web and Web 2.0.

Thomson & Craighead provide parallel insights through their artwork into the protocols and technical procedures governing the functions of networks. However, human existence and human experience has a relationship with these networks and, out of millions of interactions, evolves not metaphors but fragmented symbolisms and stories. These are telling us about a networked society’s gaze at its mediated self. And this is where art can play a special role in critiquing, communicating and sharing the nuances of this emerging multitude.

The Flat Earth Trilogy presents us with a complexity where everything is flattened out. It maps out a human psyche from an anthropological perspective. And this leaves society to deal with issues concerning the human condition entwined within a machinic evolution.

This evolution has no physical body even if real lives and bodies are its source material “each mode is displaced by machinic evolution, mixing flows and the shifting codes and overcodes of power, the base forms continue onward, written directly into the heart of the system.” [10] (Berger 2014)

To further understand this work in relation to the machinic evolution, the networked gaze, and human interaction, I feel there is some value in considering hyperreality “…a condition in which what is real and what is fiction are seamlessly blended together so that there is no clear distinction between where one ends and the other begins.” [11] Hyperreality is a post-modern term used by Jean Baudrillard, Albert Borgmann, Daniel J. Boorstin, Neil Postman, and Umberto Eco. However, if we add a contemporary flavour to what hyperreality looks like now in a networked society we come up with hyper-mediality. “What we refer to as reality very often is just mediality, and also because that’s how human nature often prefers to observe reality, you know, via some media.” [12] (Ubermogen 2013)

We can see an example of this condition in an artwork by artists’ Franco and Eva Mattes, with their performance video No Fun (2010) [13] where they staged a suicide in the popular webcam-based chat room Chatroulette.

“Notably, only one out of several thousand people called the police. Moving beyond the aspects of shock and provocation, this touches on a basic question: What does “reality” mean in the digital age?” [14] (Eva & Franco Mattes)

The Flat Earth Trilogy throws up many questions and you’d be forgiven for thinking we need another book to fully examine the ramifications of these artworks. Instead let me to refer you to other related texts by Tom Snow, Edwin Coomasaru, Jo Chard, and Alan Ingram by clicking here http://www.inmg.org.uk/archive/thomson-craighead/catalogue/

Shifting Sands.

Clive Gillman in his essay in Flat Earth says “if artists are to find a way to assert a commentary or expression through these emerging forms of contemporary media, they will have to do this by reconciling the resistance of these new media objects to be ordered into a form that may represent a recognisable notion of artistic intent. And it is into this challenge that Thomson & Craighead pitch themselves.” [15] (Gillman 2013)

It is not the audiences who have difficulties with emerging forms of contemporary media it is the mainstream art world, and this is most of its magazines, galleries and museums. From our own experience of showing art and technology at Furtherfield Gallery, audiences tend to be adventurous and open-minded regarding their experiences with technology and societal issues. And yet the art world has had difficulties making a place for this work.

Sarah Cook and Christiane Paul, both curators well versed in the field of media art, have tirelessly offered us convincing arguments why this is. Christiane Paul says, “Many curators and other practitioners in new media seek to “teleport” the art out of its ghetto and introduce it to a larger public.” [16]

Sarah Cook says “artists who are really working with technology are still redefining art. So they’ll always be “in emergence” [..] They always will try to change the boundaries of what we think Art is and challenge the institutions that show it.” [17] This is true with Thomson & Craighead’s installation and networked artwork. It is plugged directly into a larger, expansive, worldly discourse, in contrast to traditional modes of artistic and news presentation which are highly restrictive and contained within their mediated monocultures.

Gillman proposes that Thomson & Craighead are pitching themselves to create art which is a recognisable notion of artistic intent, and other artists should do this also. I am assuming this is so the work is recognisable as ‘art’ to the mainstream artworld and its traditional remits. This is a strange ask if you are an artist who is truly exploring further than what is typically expected by mainstream art culture. I would argue that artistic context and its values are not fixed and that’s the point. If artists become too self conscious in trying to make their art look like an art that “fits”, it then looses its imaginative edge and critical reasoning.

It’s a difficult balancing act if the artist is examining deep or necessary questions whilst the current art world is lagging behind in so many ways. Julian Stallabrass sees this lagging behind as a political issue. In his book Contemporary Art: A very Short Introduction, he critiques the blocking of emergent, and critically engaged artistic expression as part of a ‘New World Order’ where we are constrained by a compliant culture controlled by the rampant demands of a corporate elite, who only consider art in terms of economics, markets and brands. And these restrictive and dominating frameworks are dedicated to the neoliberal promotion of privatisation and growing inequalities.

In his article ‘Reasons to Hate Thomson & Craighead’ he says “At this point, the art professional sees a world crumbling, visions of empty galleries, unique works owned by everyone, a stuttering and then failing of artspeak amid a mass proliferation of ‘work’ and comment, the autonomy of art ruptured, artists and dealers redundant, in short an economy broken and the sacred polluted with the profane. Naturally, representatives of the old order, more or less sharply aware of dark clouds gathering at their horizons, have good reason to hate Thomson & Craighead.” [18] (Stallabrass 2005)

Thomson & Craighead’s work connects with people and they know this because they use content and themes people are thinking about in their everyday lives. This is what makes the series of documentary artworks so powerful. It assembles what is going on in the world in ways that traditional documentary and news channels are not. And this is their real challenge, because if they continue to reflect human culture as it happens with works like October – a documentary artwork about the early rise and fall of the Occupy movement – they will be highlighting messages from a world of people in need of something different than what is currently in place, whether this is deliberate or not. This art has a strange irony, it not only asks us what a documentary is, but it also asks what is news?

The End.

The End is a site-specific artwork first shown at the Highland Institute of Contemporary Art in 2010, Scotland. It is situated in one of the gallery rooms at H.I.C.A that has a large, wall-sized window looking out onto the countryside in the Highlands. It is an intervention into the space where the words ‘The End’ are fixed onto the glass in a style and scale one might associate with the end credits of a movie.

The combination of the outside natural environment, the galley building with its large glass window, and the added text, are assembled together to build a whole artwork. If any these components were taken out of the assemblage it wouldn’t work. This tells us how well crafted Thomson and Craighead’s work is and how much attention is paid to detail.

When looking at The End, one cannot help feeling a little out of sync. It is like a monument or an obituary for a lost world or lost time when we were all standing on solid ground and felt we knew what was real and not real. The End brings into play the rhythms of a larger natural environment and works as a bridge between two worlds or the illusion of it. It reminds us we are no longer experiencing the world face on or directly, but the world is re-introduced to us mainly through screens, televisions, mobile phones and our computers. It also invites us to imagine as we look out on the beauty of the natural world that we are viewing the end of our own role in the story of humanity.

The Situationist, Guy Debord said that people’s alienation was once about having things and claiming better working conditions, but then it moved onto being about a state of appearing. Meaning, it is not producing things, or even owning things that drives society but rather how things appear and how they make us appear. The glass acts as a filter and an interface, a place of safety distant from the touch of the wild. Its physicality, metaphors and symbolism offers a poetic moment for us to consider how perceptions about ourselves and ideas concerning real-life have changed, and what this means.

On the DCA website as part of its commentary about the book, it says Flat Earth presents Thomson & Craighead as pioneers in the field of new media for nearly twenty years. Sarah Cook and Christiane Paul also deserve credit as pioneers for recognising, supporting and dedicating their lives to creating the contexts in contemporary art culture for Thomson & Craighead’s work and other artists’ works. Also, Cook has edited a fine publication. Flat Earth is well designed and the whole book is meticulously well put together with quality images throughout. The mix of inteviews and essays with Thomson & Craighead give the reader a well balanced overview of their the art and their ideas, it is unpretentious and explores their focus as creative and thinking individuals artistically, conceptually and critically. We need many more of these types of books to support this dynamic and ever-changing field.

Thomson & Craighead dig deep into the algorithmic phenomena of our networked society; its conditions and protocols (architecture of the Internet) and the non-ending terror of the spectacle as a mediated life. When reading the Flat Earth publication, you get a clear impression of their conceptual rigour. They know their place and role as artists in society and this is well presented in the book. Their collaborative journey has remained faithful to the World Wide Web, and the Internet as a focal point and a content provider for their art practice.

It would be simplistic to assume they are embracing technology as a celebration of its progress. Their critical scope examines big issues and this is evident in Flat Earth. They belong to a generation of artists who are experimenting with real time data, networks, web cams, movies, images, sound and text; as part of an anthropological venture that studies humanity’s relationship with technology, alongside the inane and profound nature(s) of the human and non-human condition. We exist at a point where ubiquitous computing now redefines our point of presence, shifting our perceptions in reference to cultural tags and repeated experiences of mediation. They successfully critique these changes. Not only to other artists, curators and galleries, but to all who are being transformed by technology and this is what makes them essential and contemporary.

Thomson & Craighead are not just making and showing art they are also presenting questions. These are not invented questions they are already out there. But, just like some need an interpreter to translate different dialogues they are assembling for us the dialogues of an emergent multitude.

Some have proposed Jennifer Chan to be part of what has been termed as the post-internet era. But, this is an inadequate representation of the spirit, criticality and adventure at play in her work. Chan’s awareness and use of the Internet reflects a way of life, that situates its networks as a primary resource. Chan lives amongst various worlds and engages in different shades of being; a self-described ‘amateur cultural critic’, a net artist, a media artist, and academic. Her work exists both online and in physical realms, it is always present and contemporary. This is because her work lives in a world where the scripting of official art definitions loses its power. People have exploited technology to facilitate new behaviours where the artist or art amateur redefine what art is on their own terms. We are now in a post-art context. It reflects a very real, societal shift. Mainstream art culture no longer owns the consciousness of art, Chan and others like her are pulling it apart.

Marc Garrett: In your video Interpassivity a kind of docu-performance made for the exhibition REALCORE, you’re in a park spraying a brown cardboard box, silver. As you go through the process of walking around the box whilst spraying it, you comment on the object’s formal aspects. But, what you mainly discuss are your own personal views about contemporary art. It then becomes apparent that the box is a prop for the performance, enabling the subject to be explored.

Alongside your interpretations of the work my own thoughts on the subject feel as though they are included in the conversation. I know as a viewer, that the artist is not aware of my thoughts on the matter. However, it feels like there is space for me to be a part of the conversation. Not literally through a feedback system or interaction, but as an individual considering your personal questions. The artwork knows I am experiencing it, it knows that a consciousness out there is somehow engaging with its dialogue.

It is clear you are in tune with the feeling of dysfunction. You say, “I need to spit out some creative truth”. On hearing this, I was not sure whether this was a parady, irony or an expression of despair, or all these. You also say “contemporary art is removed from our everyday feelings”. As you express these words I begin the view the box as a symbol of contemporary art as a centralized, institutional monolith? So, before I unwittingly place my own meanings onto the work could you tell us what it means to you?

Jennifer Chan: Interpassivity is the instance of something cueing an audience to feel a certain way, such as canned laughter to stand in for humoured social reaction to jokes in a sitcom– even when it’s not funny. I titled it that because I felt like another art student trying to convince herself or the viewer what she made is art. I feel embarrassed about this self-aware but privileged complaining. A few people have found this work online and screened it, but I’m still mortified to watch it with them.

I made that video because I think a lot of contemporary art is sterile, mannered and removed from emotion. I wasn’t thinking of Donald Judd at that point but I could see the box standing in as a poor attempt at work, like his work. What I was working on (or seven years of art education) had little to do with what was happening in my life. (So to answer your question, yes, it is despair) Using my flipcam and talking over it was immediate for recording those ideas. It’s also a big trope of Canadian video art… a breathy voiceover conveys something serious and personal.

re: REALCORE. The title came about as a play on the idea of “real life”, or face-to-face life away from keyboard. Likewise, users would say “irl”(in real life), or “so real~” in Facebook comment threads to joke about the divide between online/offline contexts. The curator David Hanes felt the video was important to contextualize my use of sincerity and clichés, I was not being ironic in my intention. Arielle Gavin and Jaakko Pallasvuo thought it was questionably ironic and an emotive perspective on the Internet as a form of new sincerity.

I later found that someone wrote a paper by someone who coined “realcore” as a kind of amateur user-generated porn, which is a cool double-meaning. The “interpassivity” video was used to promote the show online but I showed my kitschy found footage videos on twisted pizza box plinths for the show. This was my fuck-you to geometric minimalism and boring white plinths, but I suppose it resulted in a different take of it…

MG: In one of your recent videos “Grey Matter” when watching it felt like I was immediately pulled into a remixed world of teenage celebrity, products and brands, dripping in an orgasmic noise of techno-capitalism. Most of it is found footage, images, video and sound remixed into an edited compilation. Running through the video in between the high octane fuelled cuts and glitches, are messages to the Internet user who chances upon the video. These messages feel like they are from an individual voice but also of a multitude – caught up in a constant state of mediated folk hedonism.

What intentions lie behind this work as an artistic explorer of the entertainment culture you have remixed?

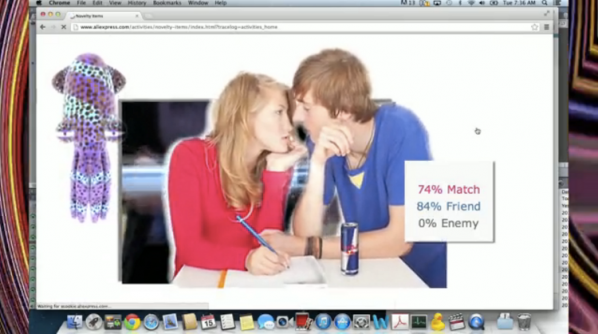

JC: Grey Matter is a first person account on feeling politically inactive online while having access to a wealth of information. I wanted to use remix in a confessional manner, so I combined obscure nostalgic media with embarrassing statements. The video begins with sped up footage of early 3D simulator ride called “Millennium Bug”. Y2K was the first technological “crisis” I recalled with clarity when I was growing up. The rest of the video includes cynical commentary on online spaces I’ve engaged with in the past year. (shopping on aliexpress.com and lurking people on OkCupid) “Little Prince” is compressed 25 times and sped up by 400%. I included old profile pics and some summary text from my OkCupid profile–I thought it was quite telling about how I wanted to be seen online and irl. I think it’s possible to feel mutually exclusive feelings at the same time, or maybe the experience of being active on different social networks produces a kind of schizophrenia. Collaging Internet pop culture is a way to appreciate it-as artifacts-in a complex light, and to be critical of it by acting out within its language.

MG: What do you find fascinating about popular culture on the Internet?

JC: Anything minuscule has the potential to be popular amongst disparate users and they form vernaculars to talk about their interest in that. I find that desire relatable. That is what I think of as “community” online. It’s based on human interest and media fandom. Justin Bieber is made into something of a scapegoat for the first world’s shortcomings; people who like his image/music idolize him, and people who hate him are waiting for him to crack. Both are forms of fanaticism (one based on affinity; the other on hate-watching something.) Supercuts of Justin Bieber hairflips, object crushing fetishists, disease forums, long threads debating a detail…etc. I like the solipsism and intensity of all that.

MG: Can you share with us some of your critical insights and personal pleasures on this subject?

JC: Pop culture is paradoxical and audiences selectively enjoy it. (like teens dancing to hip hop with irreverence to its violent or sexist content.) Consuming and sampling pop allows people to indulge into its meanings, and through this there is a reconsideration of what “the masses” find important. Like the use of “users”, “masses” is what cultural studies calls everyone or everyone except-you. But every “user” has a specific relationship with interfaces and platforms, so they aren’t so homogenous.

Pop culture is also political. There was a time when more people voted for American Idol than the US elections, and if 10,000 people showed up to the 2012 cat video festival, entertainment is generally more seductive than current affairs–until there is a gatekeeping emergency (like mainstream media not covering the early days of Occupy). In terms of “internet pop culture”, perhaps traffic with social networking has overtaken porn and gambling online, but social news is also a kind of entertainment.

MG: Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied in their book Digital Folklore they celebrate everyday people’s use of personal computers with “glittering star backgrounds, photos of cute kittens and rainbow gradients”. They value the non-professionalism and amateur spirit that has come about from millions of people enjoying the Internet since it started. There is a difference now, the Internet masses have been shifted and prodded into large web 2.0 frameworks such as Facebook, and an abundance of personal web projects have been lost since.

And, like them do you find reassurance or a personal connection with the Internet Amateurs of the world?

JC: In context of new media art, it’s probably more accurate to think of amateurs as people who don’t self-identify as artists or technicians. What non-artists do with software and video appears facile, sincere, and intuitive. I make amateur-looking work to dialogue with that.. I like to say something dumb to say something serious. Something that’s made simplistically and filled with kitschy references can be packaged as critique that also appeals to non-art audiences.

I caught the tail end of the homepage-o-sphere/webring 1.0 period. Non-artists made personal websites out of a genuine interest in something. tumblr and pinterest is used in a same way today–to collect indiscriminately. Like 2.0 frameworks, the early internet also had free webpage hosting that users relied on (Geocities and Lycos). Personal website design isn’t over either; net artists still make them or bind together to create their own sites (like tightartists.com). I think I have an idea of what you mean though; it was less commercial and there weren’t as many distinct “most-visited” places online.

I made a lot of gothy dark art on DeviantArt before I knew about contemporary art, and my sensibility towards Photoshop was more romantic and impulsive without the baggage of art education. Maybe this “revival” cult of amateur-looking digital folklore happened because I/we exoticize that kind of amateur production. Web vernaculars have also become stylized and this aesthetic is shared with seapunks and filmmakers. Artists need to adapt to that.

MG: What do you feel is still alive and open for everyday online expression and play, in respect of what Lialina and Espenschied perceive as Digital Folklore?

JC: I think a lot of emerging artists have a greater awareness of obsolescence and upgrade culture than we give them credit for–while still complacent to the socialization structures on Facebook. Many seem more interested in navigating these networks to question their inner control mechanisms than overthrowing them or innovating new ones. It can be simple things like friending as many users as possible, looping webcam feeds, archiving and re-uploading banned content on different platforms, having an anonymous/alternate personas/using multiple accounts…etc. People like glitchr and Ian Aleksander Adams are always looking for ways to use a system against its intended functions in the same way jodi did all the cheat moves in max payne CHEATS ONLY. I admire glitch practices for that.

There’s also the possibility for re-appropriating anything to rebrand or critique particular communities. I think Angela Washko and Jaakko Pallasvuo are doing this in a compelling way that covers a large territory between art and Internet culture.

MG: So, what are you working on at the moment?

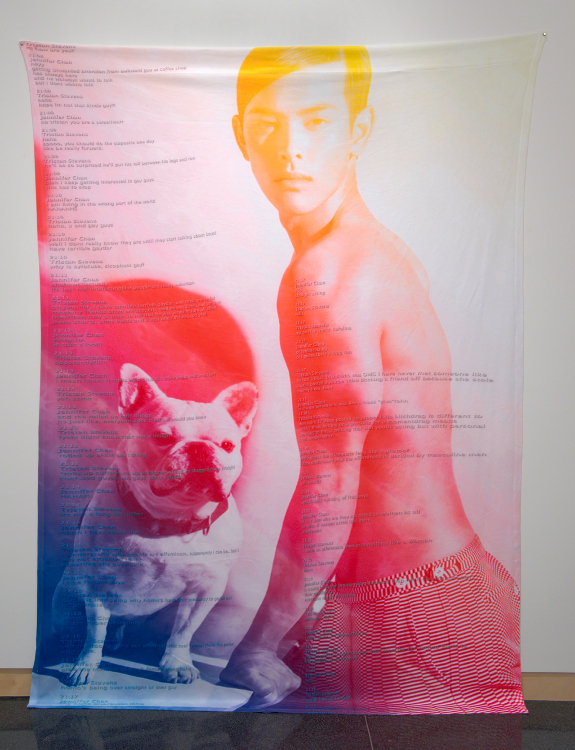

JC: <–for some reason this sounds less perverted than if I were an old guy doing this to teen girls but its really just as perverse–>

I’m observing what young adult/teen boys do on YouTube: bulking up, performing dares, talking about how to pick up a White/Asian girls etc. I’m also making a video about Asian guys (both diasporic, Asian American, and more specifically, Korean and Taiwanese men) and their interpretations of mediated masculinity. There is something disturbingly tantalizing in terms of how they have learned to look at the webcam as if they are boy band stars yet they are not fully grown men. A lot of this is informed by growing up in Hong Kong, and knowing that fashion and romance, is inspired by many “neighbouring” cultural media from Japan, Korea and Taiwan even though American/British influence is also prominent in the club scene.

Here are two images from my late installation that will foreshadow this interest. It’s chat text over layered on modified fashion and makeup adverts targeted at Korean and Chinese men, and printed onto micro-fibred bedding. I feel like they’re treated as pleasant freak shows on tumblr but this imagery is a banal, idealized kind of masculinity in Asia. I think western facial features are really common amongst these popular images of Asian-ness, and most would tend to read it as aspiring to western culture, though the hyperfemme “doll” look or metro-masculinity has been a regional style since the 90s.

Chan’s work reflects an emerging condition described by Zizek as “interpassivity” in which our engagement with interactive experience has lost traction and is replaced with “its shadowy and much more uncanny supplement/double “interpassivity””[1], a “Fetish between structure and humanism”[ibid]. We are pulled into a paradox, where ‘interaction and passivity’ are joined together as spectacle of constant mediation. Millions have joined online centralized, megastructures such as Facebook, and this is not a black and white situation. Many are coerced from social and consumer pressures into the state of being seen as interacting. As the futuristic time machine streams onwards at high-speed, agency slouches into a spurious and distant dream. Others and the same are enjoying the flow for the sake of self expression within these scripted frameworks.

Chan’s work critiques, plays with, and exploits this networked, social intervention, as well as her viewers’ desires. Her imaginative palette revivifies questions about agency, passivity, sexuality, privacy, individuality, behaviour, networked consumption and its production. These remixed artworks have much material to work with, as the endless ether of everyday noise is uploaded and distributed through blogs and social networking sites; then returned into the ether as cut-ups where a transforming culture is engaged in its own mutation.

Its noise engages us whether we enjoy it or not, in the medium of “interpassivity”, and we all find ourselves caught within this spectacular enticement driven by the Netopticon. “On a holiday trip, it is quite common to feel a superego compulsion to enjoy, one “must have fun” — one feels guilty if one doesn’t enjoy it.”[ibid]

Jennifer Chan – http://www.jennifer-chan.com/

Heavy MetaVernacular video after the popularization of the internet

http://jennifer-chan.com/index.php?/curatorial/heavy-meta/

SELF-LOVE A non-consensual exhibition of emerging net art

http://jennifer-chan.com/index.php?/curatorial/self-love/

New Insularity Peer backpatting. A screening of works by friends and users whose works I admire.

http://jennifer-chan.com/newinsularity.html

Feeling VideoThe affective appeal of antisocial video

http://jennifer-chan.com/index.php?/curatorial/feeling-video/

Trivial Pursuits Distracting “new media art”

http://jennifer-chan.com/index.php?/curatorial/trivial-pursuits/

We live in a world riddled with contradictions and confusing signals. Our histories are assessed, judged and introduced as fact yet there are so many bits missing. We accept what is given through soundbite forms of mediation and end up using the easy bits as our defaults, and build up these assumptions as our ‘imagined’ guidelines. This article examines how these accepted defaults are being challenged by contemporary artists. Each have expressed their own particular (unofficial and official) form of interventions at the Tate Gallery. Featuring art works produced by artists’ and art groups, such as Graham Harwood, Platform, IOCOSE and Tamiko Thiel, we explore their connected enactments and critiques of the existing conditions. Whether it is based on economic, ecological, historical, political or hierarchical situations, they are making others aware of their creative arguments in different ways.

You will not see them accepting an award at the Turner Prize. But, their work has become as equally significant (perhaps even more) than, the mainstream art establishment’s franchised celebrities. There is now wider art audience out there, connected to the Internet and they are aware of the issues of the day. Yet, this context is not reflected back by traditional art venues and art press. Instead, we receive more of the same. The mainstream version of contemporary art has found its allies within a global and corporate culture, where business dictate’s art value. Critical and imaginative contexts contrary to neoliberal demands, are left aside. We cannot trust the ‘official’ art world to produce a realistic vision of what contemporary art really is. It is up those who are not reliant on or diverted by these powerful frameworks and elusive economies, to bring about a different set of examples of an existing parallel world which is thriving, and so much more interesting and relevant.

“Art is subject to a double protection. In the market, it is shielded from unwarranted treatment through controlled ownership. In the museum world, experts decide what should be seen, alongside what, with what interpretation and in what circumstances. A wide public is courted but allowed no power over what it sees. The very ethos of this culture—of exclusivity, elitism and control—is now at odds with the culture people make themselves.” [1] (Stallabrass 2011)

“From adolescence I had visited the Tate, read the Art books and generally pulled a forelock in the direction of the cult of genius, on cue relegating my own creativity to the Victorian image of the rabid dog. We know well enough that this was how it was supposed to be. The historical literature on ‘rational recreations’ states that, in reforming opinion, museums were envisaged as a means of exposing the working classes to the improving mental influence of middle class culture. I was being inoculated for the cultural health of the nation.”[2] (Harwood)

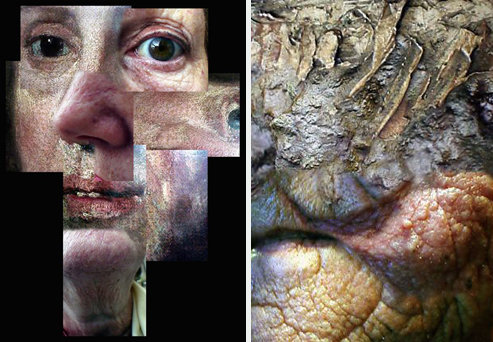

In 2000, Graham Harwood[3] received the first Net Art online commission from the Tate Gallery London for the creation of his art work ‘Uncomfortable Proximity'[4]. Viewing the visual images/collages created by Harwood; reminds one of the moment when Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray'[5] views his disfigured self portrait. Considered a work of classic gothic fiction with a strong Faustian theme. The facade of his own idealised beauty is revealed as something less attractive and deeply disturbing. Harwood’s approach in offering the viewer to click on the image to see what lies behind shows the people he represents, to be seen as lurking secrets, as ghosts, mutants, lepers and outsiders.

![Dorian in front of his portrait in the 1945 film The Picture of Dorian Gray.[6]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/dorian-gray.jpg)

“Tate Britain stands on the site of Millbank penitentiary incorporating part of the prison within its own structure. The bodies of many of the inmates remain concreted into the foundations of the building. The drains that run from the building to the Thames, a stones through away, bleed this decay into the silt of the Thames.”[7] (Harwood 2006).

Harwood brings to the fore the forgotten people. The lives of others, whose stories are now just distant markers of a past, dominated by a colonial history. These are the losers, the then ridiculed and exploited chavs of their day.

“‘Chav’ is an insulting word exclusively directed at people who are working class.”[8] (Jones 2012).

The first section of ‘Uncomfortable Proximity’ maps high society rituals of tastefulness and its inherent hypocrisy. The second, representations and histories of different people such as friends, family and others, who are unseen in terms of the institution’s remit of tastefulness. To do this he used the historically respected paintings (on-line images) on the Tate web site by artists such as Turner, Hogarth, Hamilton, Gainsborough, Constable and others.

“This work forced me into an uncomfortable proximity with the economic and social elite’s use of aesthetics in their ascendancy to power and what this means in my own work on the internet.”[9] (Harwood 2006)

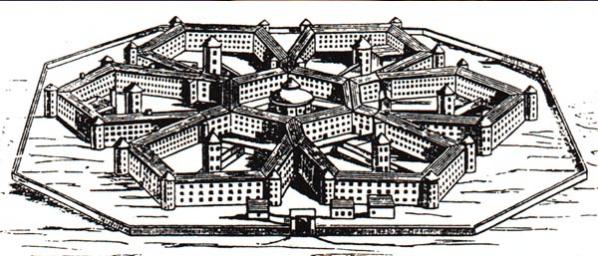

London’s Tate Britain area, before it was reconstructed into an art gallery, in the early 19th century was a national prison. The Millbank Penetentiary, was hailed as the greatest prison in Europe, at a cost of £500,000 it was finally built in 1821. It was Jeremy Bentham, the British philosopher and philanthropist who designed it using his pionering ideas creating the prison as a ‘panopticon’.

“At its centre was the Governor’s House, which allowed prison guards to keep watch over 1,500 transportation prisoners housed in separate cells in the surrounding pentagonal blocks. There were three miles of cold, gloomy passages: the turnkeys invented a code of chalked directions to stop getting lost in the maze!”[10]

Sentenced prisoners were processed in the prison each year and up to 4,000 would then be sent off to distant lands, such as Australia. Within the panopticon, prisoners would not know whether they were being watched or not.

“The panopticon Panoptic power built into the architecture of Benthams’ prison Prefigured what some refer to as the “electronic panopticon” or “surveillance society” which includes: the mass surveillance & collection of data by government on populations; the surveillance & collection of data on consumers for marketing purposes; the management surveillance & control of the workforce by industry.”[11] (Ballantyne)

Somehow Harwood manages to bite at the hand that feeds him, “the artist very deliberately used the work to question the role of digital media in promotion and collection. His Web site copied the Tate publicity site, with his own content inserted, causing substantial institutional disruption around the marketing department because the Tate’s Web site, in common with those of many art museums, was seen primarily as a marketing tool, then perhaps as interpretation, but never before then as a venue for digital art.[12] (Cook, 2001).

At his point it’s worth considering how some artists have experimented with the behaviour of parasites in order to explore their artistic autonomy at the edge of things. The rise of hacking and ‘art and hacktivism’ has brought about artists reimagining their creative intentions not in terms of existing within the frameworks of galleries and museums (although many do show their work in these types of venues as well). Many have chosen not to comply to the ‘official’ script of marketing demands and values imposed by mainstream art world hegemony, or concede to centralised web 2.0 structures dominating Internet culture and our mobile networks.

“The word ‘parasite’ comes from ‘para sitos’, meaning ‘beside the grain’, and refers to those animals that take advantage of grain stores to feed. […] they are not part of the restricted economy of exchange, profit, and return that is at the heart of capitalism, and to which everything else ends up being subordinated and subsumed. Thus they find an enclave away from total subsumption not outside of the market, but at its technical core.”[13] (Gere 2012)

![Haw under arrest before the State Opening of Parliament in 2010. Photo: Jeff Moore. Telegraph.[14]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/haw-police_1924712b.jpg)

In June 2001, activist Brian Haw began his protest against the economic sanction on Iraq, opposite the Palace of Westminster in central London, until his death of lung cancer in June 2011. He earned himself a place in the history books for what he devoted ten years of his life doing, camping in a tent outside the Palace with numerous placards. First it started with only a few banners and then through the years the number of banners accumulated, with its content pointing out to the public and politicians, the huge suffering and killing of people in Iraq supported by the UK government. “Even as fresh attempts were begun to oust him, he won an award for being that year’s ‘most inspiring political figure’.”[15] (Stevenson 2011)

In 2006-7 British artist Mark Wallinger created an installation called State Britain, replicating all of the tents and banners at Parliament Square. Featuring it as his main entry for the Turner Prize at Tate Britain. “Faithful in every detail, each section of Brian Haw’s peace camp from the makeshift tarpaulin shelter and tea-making area to the profusion of hand-painted placards and teddy bears wearing peace-slogan t-shirts has been painstakingly sourced and replicated for the display.”[16] It also included copies of other people’s contributions, consisting of messages and banners amassed by Haw over the years, as a constant and dedicated daily protester, winning Wallinger the Turner Prize.

“…the larger hand-painted signs are defanged by their new context. “Beep for Brian,” once an irreverent call-to-arms taken up by many motorists plowing through the Westminster traffic, has become an absurdity, un-honkably sealed within the echoing marble box of the Tate. Never has the notion of the “lost original,” that timeworn legacy of Duchamp’s ready-mades, carried such a melancholic charge.” [17] (Street)

In contrast to his peers who also came out of the YBA (BritArt) movement in the late 80s and early 90s, which includes individuals such as Damien Hirst, Rachel Whiteread and Tracey Emin, Wallinger is a committed socialist. Damien Hirst was “the leading light in the YBA movement, is a famously good businessman and is now one of the richest men in England.”[18] (Shaw 2011)

“I did feel removed from the YBA thing. But it almost immediately raised people’s game. There was money and there was an audience. Or, to be strictly accurate, there was money – it really was a very targeted strategy to begin with – and the audience came along a bit later.”[19] (Wallinger 2011)

Wallinger’s comments about the audience coming along later rings true. The power of money and marketing created an audience that before,was not there, specifically for the YBA’s. Emerging artists at the time, who were not part of this elite where left out of the picture, not because of their art but because of their lack of connections with YBA circles. Many artists casted their creative intentions and values aside and re-invented their art in accordance to YBA themes, with a hope they would be accepted by this (then) new, mainstream art establishment. From the early 80s, and well into the 90s, UK art culture was dominated by the marketing strategies of Saatchi and Saatchi, a formidable force in the advertising world. The same company had been responsible for the successful promotion of the Conservative party (and conservative culture) that had led to the election of the Thatcher government in 1979. Saatchi and Saatchi Applied their marketing techniques and corporate power, with an accomplished parallel coup within the British art scene, creating an elite of artists who embraced the commodification of their personalities alongside depoliticized artworks.

Stewart Home proposes that the YBA movement’s evolving presence in art culture fits within the discourse of totalitarian art “the critics who theorise the yBa understand that by transforming art into a secular religion, rather than a mere adjunct of the state, liberalism imposes its domination over the ‘masses’ far more effectively than National Socialism. The focus, especially in the mass media, must be on the artists rather than the artwork.”[20] (Home 1996)

“To be an artist is to contend with the present, and there are not many other careers that afford the freedom to radically examine life and society. To put it bluntly, if artists are studying and writing more about politics, culture, and education, it’s probably a reflection of the unprecedented dysfunctionality of the societies in which they live.”[21] (Deck 2005)

Every now and then something slips through the highly taught institutional web of marketed ideologies and it causes a state of ‘healthy’ unease. One such intervention is the recent collaborative project Tate à Tate.[22] It is a public intervention consisting of an audio guide that people can download onto their MP3 players or mobile phones. The material is accessible from http://tateatate.org – you download a selection of audio files and then take a physical tour to Tate Britain. It is best experienced if you take the Tate Boat to Tate Modern, or you can listen at home. The artists selected to make the sound works are Ansuman Biswas, Phil England, Jim Welton, Isa Suarez, Mark McGowan and Mae Martin.