Featured Image: Julian Rosefeldt Manifesto, 2014/2015 ©VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016

Entering the darkened gallery space in the side wing of Berlin`s Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, the visitor first encounters a projection showing the close-up of a fuse cord burning in the dark. Shot out of focus its sparks are flying in slow motion, a firm clear female voice comes in beginning a monologue which includes familiar lines and passages: “I am against action; for continuous contradiction, for affirmation too, I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense. […] All that is solid melts into air. […] I am writing a manifesto because I have nothing to say.”. The fuse cord gradually exstinguishes without leading to an explosion.

Quoting parts of the manifesto of the Communist Party, Tristan Tzara`s Dada Manifesto as well as pieces of Philippe Soupault`s “Literature and the Rest”, the 4-minute video in its function as “Prologue” sets the tone of Julian Rosefeldt`s exhibition “Manifesto”. The opulent 13-channel installation is a homage to the textual form of the artist manifesto – in Rosefeldt´s words “a manifesto of manifestos”. Inspired by the research for his previous work “Deep Gold”, Rosefeldt began looking further into the genre and its poetics. From about sixty popular art manifestos – the earliest from 1848, the latest from 2004 – he collaged twelve new powerful and entertaining manifestos. Said manifestos serve as the source for each of the thirteen videos (a prologue and 12 scenarios) delivered and performed as monologues by Oscar-winning actress Cate Blanchett.

In every film, an extremely versatile Blanchett morphs into another role: From homeless man to broker, newsreader to punk, puppeteer or scientist. Obviously these roles do not represent the manifesto`s authors, they rather show contemporary types chosen by the artist to counterpoint or stress the ideas and attitudes of the text passages they are reciting. As a CEO at a private party, Blanchett is orating in front of an affluent audience, praising “the great art vortex”. Continuing her celebratory speech, she changes the tone to amuse her crowd quoting more passages of the Vorticist manifesto: “The past and future are the prostitutes nature has provided.”. Polite laughter, glasses are clinging. Another scene shows a bourgeois American family sitting at the dining table about to say grace. Blanchett in the role of the conservative mother is leaning her head, folding her hands but instead of the usual blessing, she begins to fervently recite Claes Oldenburg`s Pop Art Manifesto which consists of a series of propositions starting with “I am for an art …” and includes such gems as: “I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.” or “I am for the white art of refrigerators and their muscular openings and closings.”.

All 10-minutes-long videos in the exhibition work according to the same principle: the art manifesto collages are delivered as monologues by Blanchett at first in voice-over introducing the scene, then in filmed action and at its climax as speech to camera. Shown in parallel and installed without spatial division, the monologues interfere with one another, and the visitor is always confronted with more than one narration. While watching Blanchett in the role of a primary school teacher softly correcting her pupils quoting Jim Jarmusch: “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination.”, one can at the same time hear her in the role of an eccentric choreographer slamming the rehearsal of a dance ensemble with the words of Yvonne Rainer, “No to style. No to camp. No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.” From somewhere else the sound of a brass band appears, introducing the funeral scene in which Blanchett is holding a eulogy consisting of a collage of several Dada manifestos. Sounds and voices overlap and compete for attention until a point in each video when all characters in sync turn towards the camera falling into a chorus-like liturgical chant, filling the dark gallery space with a polyphony – or cacophony – of interfering monologues. It is an impressive experience, but simultaneously the installing method makes it very hard to concentrate on words and ideas expressed in the manifestos.

In general, the exhibition and each of the videos are aesthetically pleasing and entertaining to watch, which is equally due to the scenography with its amusing artifices, the strong selection of text passages as well as its its star power. Rosefeldt´s opulent, multi-layered and choreographed installation blurs the lines between narrative film and visual art. Commissioned by a unique group of partners that include the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Hamburger Bahnhof and Hanover `s Sprengel Museum, “Manifesto” is in no way inferior to most cinematic productions made in Hollywood. But here´s the problem: Although Rosefeldt claims in his intro text and again in the video interview accompanying the exhibition online, that he wanted to emphasize and celebrate the literary beauty and poetry of artist manifestos, the texts are outshined by the cinematic staging of actress, setting and choreography of space. The attention of the viewer is drawn to speaker and theatrical performance, instead of focusing on the poetics and messages contained in each one of the thirteen art manifesto texts.

Another stylistic element that Rosefeldt uses attempting to highlight the manifesto texts is creating tension between text and image. Most of the settings and characters in “Manifesto” deliberately break with the performed text, which can for example be witnessed in the scene of the conservative mother reciting Oldenburg. Both were conceived by Rosefeldt to intensify the contrast between the rebellious rhetoric, idealism and radical notions of the manifesto form and the realities of today´s world. This does not work out at all times, sometimes the performances seem so exaggerated that they tip over and border on the ridiculous, the staging turns into travesty. It reinforces the impression that the exhibition is not in the first place about the texts, their content and reflective presentation, but rather aimed at the maximum achievable effect. But Rosefeldt succeeds in his intention to show how surprisingly current the demands of some of the manifestos presented are, most of them written in the 20th century. A century which was defined by historian Eric Hobsbawm as the short century and “The Age of Extremes” which saw the disastrous failures of state communism, capitalism, and nationalism. The world has more or less continued to be one of violent politics and violent political changes, and as Hobsbawm writes most certainly will continue like that.

So it is no wonder that the manifesto, also serving as a signal of crisis, is experiencing a revival. With the internet as an easy means of dissemination, the manifesto form has been revisited by a great number of single artists and artist activist groups, it spread out in every niches of the art world, and was adapted by academia and beyond. So when Rosefeldt in his statements nostalgically praises texts from the “Age of Manifestos” and states that he misses this thoughts focus in today´s discourses, one cannot but wonder if he missed the current debates sparked by texts like the “#ACCELERATE MANIFESTO for an Accelerationist Politics”, “The Coming Insurrection” by the anonymous Invisible Committee, “Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation” authored by Laboria Cuboniks collective or texts by individual artists like Hito Steyerl which became important points of reference.

Rosefeldt´s selection of manifesto texts seems random and inconsistent with his expressed intentions: Why was the manifesto of the Communist party included in an assortment of art manifestos? Or why were Jim Jarmusch`s “Golden Rules of Filmmaking” from 2002 and Sturtevant`s ”Man is Double Man is Copy Man is Clone” from 2004 chosen in a selection concentrating on 20st century texts? Instead of concentrating on canonic art movements and a few single artists, it would been more convincing to reflect how the art field since then has been trying to re-position itself within the shifting boundaries of activism, technology and aesthetics. With a subjective selection of simply “the most fascinating, and also the most recitable” texts, “Manifesto” is caught up in an acritical nostalgia to the disadvantage of coherence and focuses rather on text as performance as on persuasive messages and reflection.

As Mary Ann Caws in her anthology “Manifesto: A Century of Isms” states, the manifesto is “a document of an ideology, crafted to convince and convert”. Naturally, there also is some discomfort with or even suspicion of the manifesto form. The obvious example being the Futurists, who in their manifesto glorified speed, machinery and war. Their text largely influenced the ideology of fascism which they supported in the run up to World War II. In the exhibition, the macho-male tone of the Futurist manifestos fittingly and amusingly is performed by Cate Blanchett in the role of a female stockbroker. Rosenfeldt met Marinetti`s dream of an engineered society showing us the violent creator and destroyer financial capitalism.

Julian Rosefeldt. Manifesto

Curated by Anna-Catharina Gebbers & Udo Kittelmann

10.02.2016 to 10.07.2016

Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin

http://www.smb.museum/en/museums-institutions/hamburger-bahnhof/exhibitions/detail/julian-rosefeldt-manifesto.html

[Notes:

1. These are the minimally reformatted and slightly expanded notes for what would have been a 15-minute presentation.

2. The presentation was meant to be followed by questions and form part of the introduction to a panel discussion. Any questions in the comments here or on netbehaviour gratefully received.]

Art and money have always been involved in each other’s production. This is a Greek Drachma from 600BC with a relief depiction of a sea turtle on one side. For many people this would be the artwork, or at least the image, that they saw most frequently in their everyday lives.

In the present day, high art and high finance (or big art and big finance) go hand in hand. Blue chip artworks produced by brand name artists like Jeff Koons are collected by hedge fund managers and oil oligarchs as investments and as signifiers of socioeconomic position (while stolen Old Master paintings are used as signifiers of value in transactions between criminal gangs…). This tendency reaches its logical conclusion for now with Damien Hirst’s “For The Love of God” (2007), a diamond-encrusted platinum cast of an actual human skull complete with the original teeth. It was sold for fifty million pounds sterling.

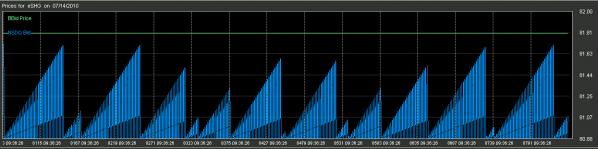

Looking inside the sale of “For The Love Of God” makes its narrative less straightforward. It was sold to a group including the artist and their dealer, making the actual figure and its ownership less straightforward than a simple sale would suggest. Nanex’s High Frequency Trading visualizations from 2010 look inside transcations in electronic stocks & shares markets, finding aesthetic forms in the activity of share trading bots. What the sawtooth waves of this bot’s activity represent is unknown: a glitch, a strategy, a side-effect. But without making these forms visible, we would not be able to ask these questions or reflect on this economic activity.

It is part of the value of art, particularly Conceptual Art, that it can afford us these opportunities for reflection and critique. Cildo Meireles’ “Insertions Into Ideological Circuits 2” (1970) overwrites the contemporary equivalent of the Drachma’s turtle with a rubber stamped message on a banknote, intruding into everyday use and circulation of currency in order to give its audience a pause for critical reflection.

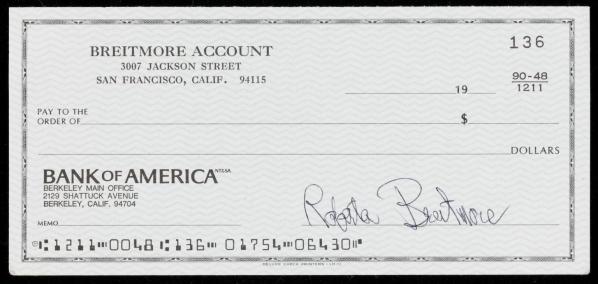

Lynn Hershman’s “Check” (1974) is signed by their artistic alter ego Roberta Breitmore, using financial transactions and their attendant contracts as a producer and guarantor of identity, literally underwriting it.

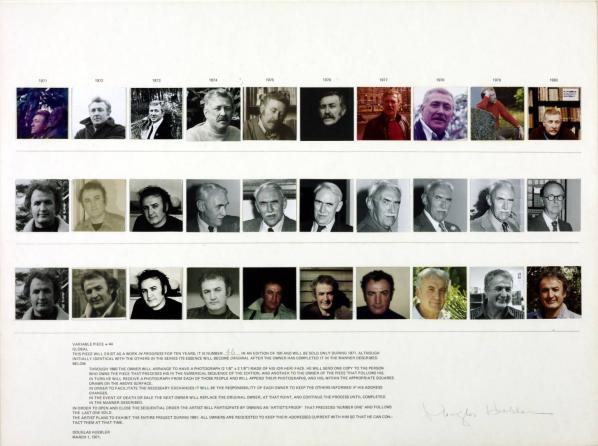

Douglas Huebler’s “Variable Piece no.44” (1971) incorporates an image of its current owner into itself each year for its first decade, in an analogue precedent for Bruce Sterling’s idea of “spimes”. When the artwork is sold a new owner appears, making the artwork’s contingent economics its aesthetic subject.

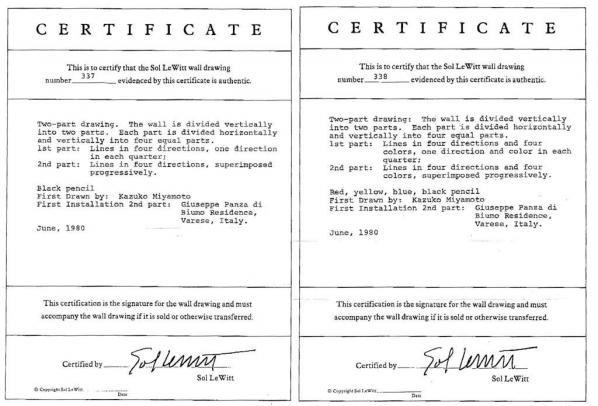

The initial critique of the ontology and economics of art that Conceptual Art represented in its “dematerialisation” phase represented as much of a challenge for the livelihoods of artists as it did to its chosen targets. One solution found early on was to produce certificates of authenticity or ownership for otherwise un-ownable art. This re-appropriates conceptual art for scarcity economics and as property, returning it to the market. Sol LeWitt’s certificates for two wall drawings (1980) demonstrate how this works. If you own such a certificate and I do not, and we both follow the instructions on the certificate, you produce an authentic LeWitt and I at best produce a forgery.

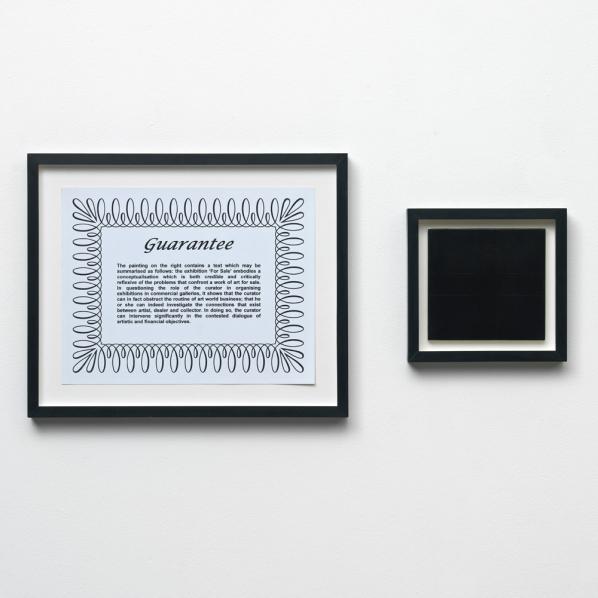

This stretegy was criticised (and parodied) within the Conceptual Art movement itself. An early Art & Language artwork, “Guaranteed Painting” (1967), contains a printed certificate guaranteeing that the painting accompanying it contains particular content and addressing the curator of the show it appears in as someone who can possibly intervene in artworld economic relationships.

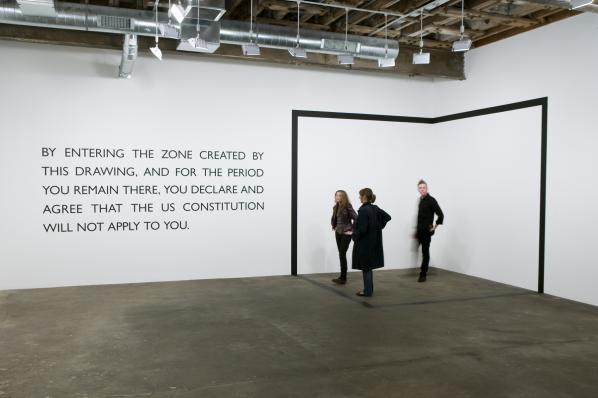

Carey Young’s “Declared Void” (2005) is a wall drawing that creates a space in which its audience enters into a contract agreeing that the constitution of the United States. Legal form as sculptural form, this is no longer about the relationship between art and money but rather between the individual, contract law, and the state. This is the kind of relationship that produces money, or at least fiat currency, and is a broader context for considering the more specific relationship between art and money.

I love this flower currency from 2005, produced by a group of Viennese artists. It’s both a LETS-style complementary currency and a use of the aesthetics of pressing flowers to allegorize and aestheticize the relationship between nature, production, and value in economies.

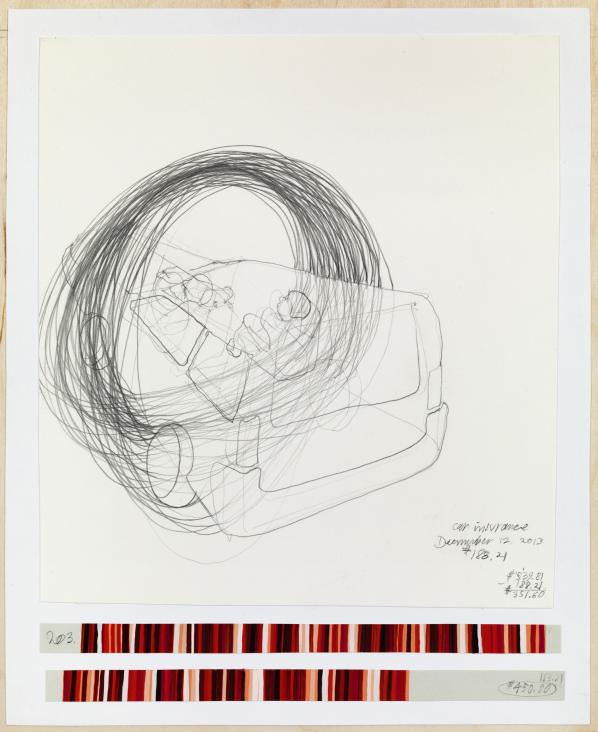

This Danica Phelps stripe drawing (2013) shows the artist’s expenditure on reparing their car. If it depicted income rather than outcome the stripes would be green rather than red. Phelps’ work combines the ledger of their economic existence with the artistic record of their social presence.

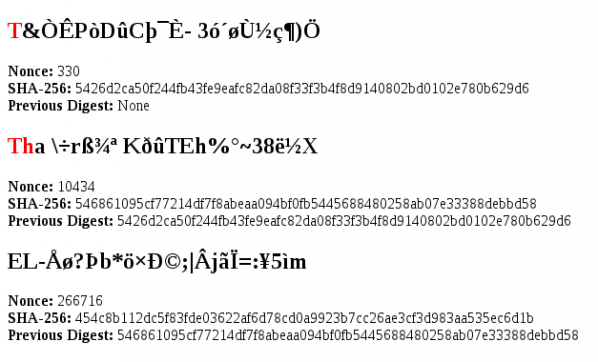

Bitcoin emerged as a critique of state-issued “fiat” currency following the financial crisis of 2008. Bitcoin is a cryptocurrency, a piece of software that runs on computers (“nodes”) spread across the network that communicate with each other to reach a shared consensus on the current state of a cryptographically-secured ledger. Every ten minutes or so these computers bundle up transactions into “blocks”, each of which refers to the previous block. This is the “blockchain”. This is yodark’s fanciful depiction of the blockchain proceeding from the first block of transactions, the “genesis block”.

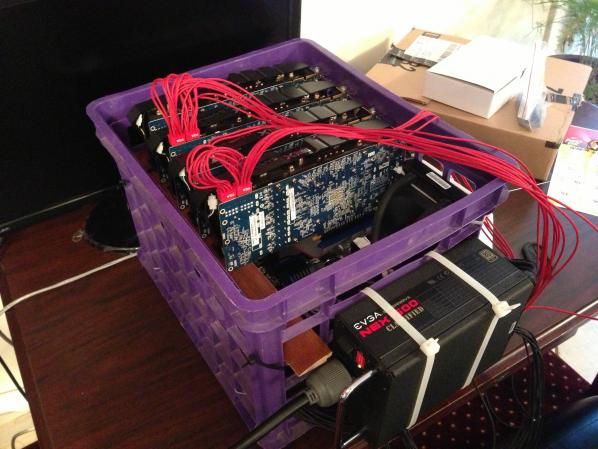

In reality news blocks in the chain are validated (or “mined”) by nodes in the network using increasingly specialised hardware, such as this milk crate mining rig from a couple of years ago. They perform difficult to solve but easy to validate sums on each block, the “proof of work”, and the first node to succeed gets a reward (paid in Bitcoins) for doing so.

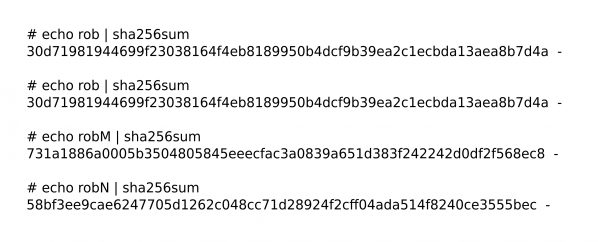

Bitcoin account addresses, Bitcoin transactions, and the proof of work system all use cryptographic algorithms. These are mathematical ways of taking data and creating an almost un-fakeable, almost un-reversable, almost unique (where “almost” means “as likely to fail as the Earth is likely to be hit by a civilization-ending asteroid in the next 20 minutes”) identity for it. The examples here show how feeding a cryptographic hash function the same data twice results in the same incredibly unlikely number, but feeding it even slightly different data results in very different and unrelated numbers.

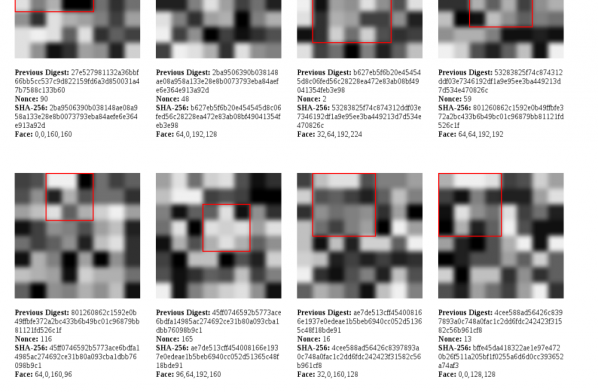

Bitcoin uses these functions to secure its network in the “proof of work” system by searching for auspicious numbers in their output (strings of zeroes in the current scheme). My Facecoin (2014) implements an alternative proof of work system in which the useless work performed is that of portraiture, (mis-)using machine vision algorithms to find imaginary faces in cryptographic hashes represented as bitmaps rather than numbers.

My Monkeycoin (2014) takes a different approach, searching for the complete works of shakespeare in textual representations of those numbers.

Cryptocurrencies can be used in lieu of fiat currency for all kinds of transactions, including artistic ones. Here the artist Eric Drass is offering a painting for sale via Bitcoin. Different means of exhange create different kinds of social relationships, buying the painting via Bitcoin is a different kind of social and economic transaction than paying with fiat currency for it via Saatchi Online.

Cryptocurrencies can be created as complimentary currencies with specific intent or for specific constituencies. This is the logo of Banksycoin (2014), an attempt to create a currency to pay for art and create a parallel economy for artistic production.

Cryptocurrency-based technology can change how individual artworks are owned as well as paid for. This is theironman’s “nxtdrop” (2014), the ownership of which is represented by shares on the “nxt” blockchain. Ownership of the painting can be changed fractionally by dealing in those shares.

There are poems, images, and other cultural artefacts embedded in the Bitcoin blockchain, disguised as transaction information. I embedded the cryptographic hash of my genome in the Bitcoin blockchain to establish my identity with “Proof Of Existence I” (2014).

This is Caleb Larsen’s “A Tool To Deceive and Slaughter” (2009). It contains a computer that must be connected to the Internet as part of the conditions of ownership, which then immediately offers itself for sale on the eBay auction site. This kind of “smart property” is a good example of smart contracts, in which arrangements such as ownership are managed by software rather or more immediately than by law.

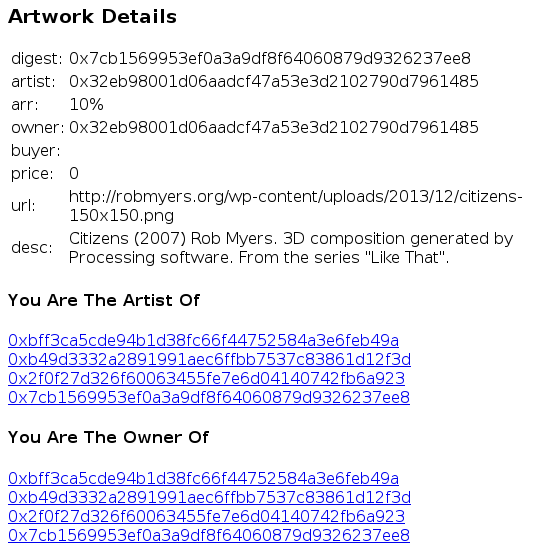

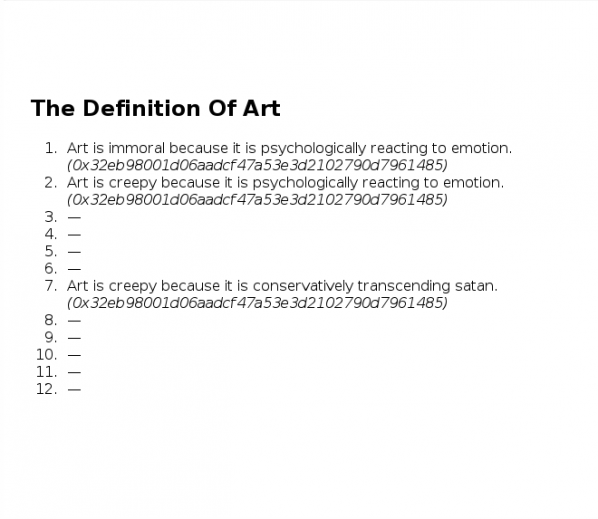

My “Art Market” (2014), uses the Ethereum smart contract system (a generalization of Bitcoin to contracts other than for the exchange of money) to record “owenrship” of infinitely reproducible digital files and allow them to be “sold” for cryptocurrency. Other systems exist to do this, such as the Monegraph and Rarebit systems.

My “Is Art” (2014) uses a simple smart contract to democratize the nominational strategy of conceptual art. The contract can be set to nominate itself as art or not with a click of a mouse and the paying of a small fee to execue the change on the blockchain.

My “Art Is” (2014) applies behavioural economics to the philosophy of art, allowing individuals to pay as much as they feel their definition of art it worth. This disincentivises malicious or unserious definitions and indicates an individuals’s confidence in their definition, using market mechanisms to price and allocate knowledge and even truth efficiently. fnord

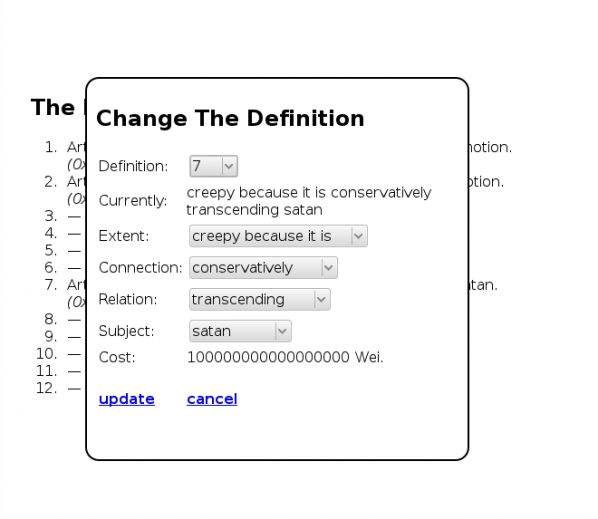

This is Art & Language’s “Index 002” (1972), a collection of the group’s writings assembled and indexed for presention in a traditional gallery setting to assert their identity and productivity at a time when their largely conversational practice might not have looked much like “art” to outside observers. Filing cabinets and photocopied sheets were contemporary information technology, later “Indexes” would use microfilm and (allegedly random) computer-generated tabulations. Their use and the production of the “Indexes” was both a solution to and a subject of the problems of Art & Language’s work. A contemporary group could use the blockchain to similarly focus and problematize their work.

The Cypherfunks are a distributed music group. Anyone who uploads a song to the SoundCloud music sharing web site tagged #thecypherfunks receives the groups cryptocurrency FUNK in return, becoming part of the group.

Dogecoin is one of the most popular “altcoins”, Bitcoin-derived cryptocurrencies that are not interoperable with the original Bitcoin network. It is the coin of an intentionally constructed culture of virtue and play, with its own argot and social norms based on Internet memes (particularly the titular “Doge” and the idea of a potlatch-like norm of tipping).

These are all more contemporary, and more complex, ways of demonstrating affiliation to a group than simply painting currency code-like letters on a canvas (this is a detail from Millais’ “Isabella” (1849). Possibly the ultimate in creating a group affiliation, or even a society, using smart contract technology is the idea of “Decentralized Autonomous Organizations” (DAOs), economic agents that exists on the blockchain and manage the resources of an organization via code rather than bylaws or legislation.

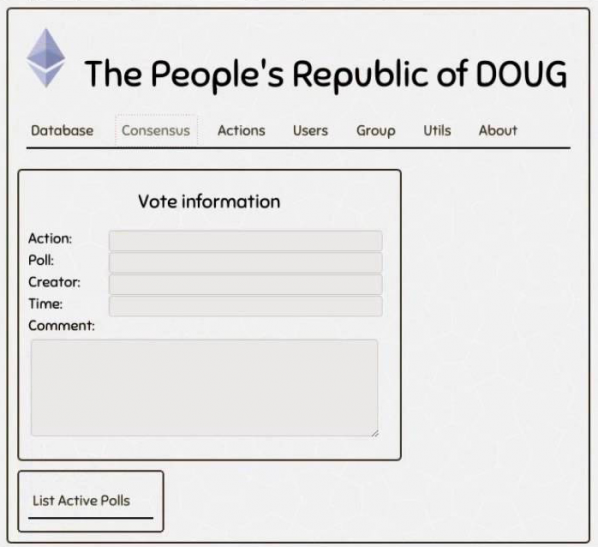

This is “The People’s Republic of DOUG”(2014), a DAO implemented as smart contracts on the Ethereum smart contract system’s blockchain. You can become a citizen, own property, vote, use its own currency in transactions, all functions traditionally provided by the state as conceived of in terms of contract law. Bitcoin’s dream of a stateless (but not property-less, making it anarcho-capitalist rather than anarchist) future realised in a few thousand lines of code. Imagine using (and/or critiquing) such a system for artistic organization and/or production.

“Now make art with it.”

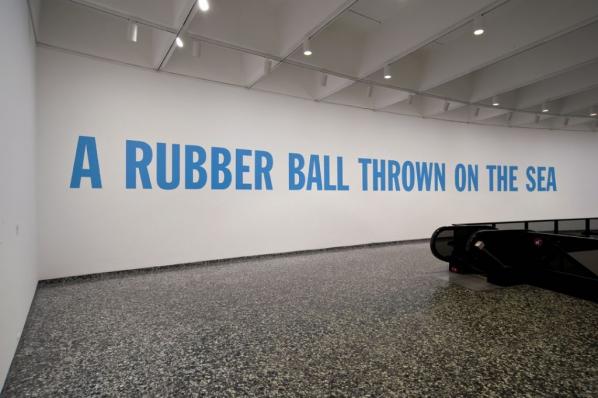

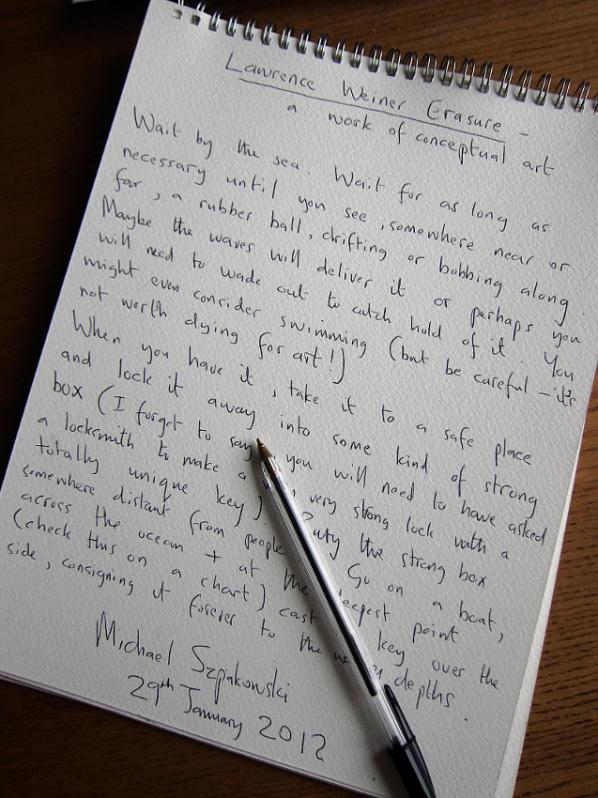

Michael Szpakowski’s “Lawrence Weiner Erasure“, 2012, presents itself as an erasure of Lawrence Weiner’s “A RUBBER BALL THROWN ON THE SEA“, 1969. It takes the form of a handwritten text on a drawing pad accompanied by the ballpoint pen used to write it and an edition of framed photographs of them.

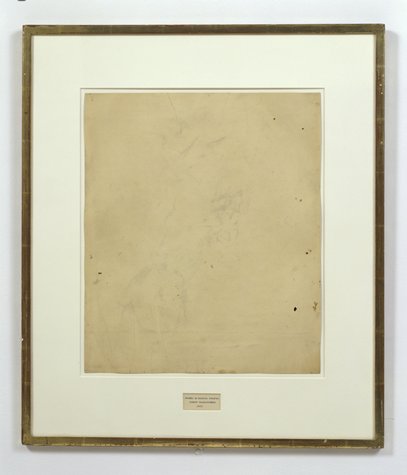

The best known act of erasure in twentieth century art is Robert Rauschenberg’s “Erased de Kooning Drawing“, 1953. The young Rauschenberg visited Willem de Kooning at the height of the latter’s fame and asked for a drawing to erase. de Kooning obliged, but ensured that Rauschenberg would have his work cut out by choosing a drawing that would be particularly difficult to erase. It took Rauschenberg a month to get the paper almost free of marks (its catalogue entry lists the medium as “traces of ink and crayon on paper”).

This was a clear act of iconoclasm and generational positioning by Rauschenberg but he was not reacting negatively to de Kooning’s work or fame. Rauschenberg had previously been erasing his own drawings but felt that this lacked creative tension. Using a de Kooning drawing gave both an aesthetic and an artworld weight to the act of erasure. Although fitting neatly into the historical era of Neo-Dada, its relational and performative content can also be read through the lens of the conceptual art of a decade later.

Conceptual art’s journey from institutional critique to critically important part of contemporary art institutions is a cautionary tale for artists with any kind of political or social aims. In the nineteen-sixties it must have seemed that an idea typed on office paper or published in a photocopied journal could never be sucked into the market for authentic artworks as defined by Greenberg’s ideas of painting and sculpture. When Art & Language were recently asked to authenticate what a dealer had been told were previously unknown prints of theirs from the sixties, they pointed out that they must be fakes as they were on “good paper”. But the very difficulty of acquiring and preserving early conceptual art, both for collecting by private collectors and for display by public art institutions, has made it increasingly appealing and valuable precisely because of its lack of physical quality.

Many artists have followed their work through this transition, the artistic equivalent of an indie band turning to stadium rock as their audience grows. Lawrence Weiner started out in the 1960s making (or in fact not making) such works as “ONE STANDARD DYE MARKER THROWN INTO THE SEA”, 1968, and “A REMOVAL OF THE CORNER OF A RUG IN USE”, 1968. These started naturally as happenings-era proposals for performances and installations that were never made, instead becoming art in themselves. Over the years Weiner responded to the need to display these simple texts in increasingly grandiose public contexts with increasingly large typographic arrangements painted onto or cut into walls and floors. I appreciate Weiner’s work but it is easy to appreciate the criticism that it has progressed more in the scale of its presentation, than in its form or content.

Against this backdrop of institutional recuperation and inflation of the history of conceptual art, Michael Szpakowski has turned to Rauschenberg’s erasure and Weiner’s concepts. Rather than recreate the current large-scale installations of Weiner’s texts, he has gone back to conceptual art’s simple material and conceptual roots with a hand-written text. I initially read the tone of voice of that text as the artist’s own. In fact it is not (as he pointed out in a private email exchange). It is a conscious part of the aesthetics of the piece and the effect it must create in order to persuade the viewer to enter into the imagined actions that it describes.

Those actions serve to undo, or erase, the action described in Weiner’s original. They undo both the action and its formal properties. The experience described in Szpakowski’s text is of a different duration and character to that described in Weiner’s. The length of Szpakowski’s text contrasts with Weiner’s gnomics very clearly. It also relates to the thoroughness required to erase a vivid drawing or concept. And it is a product of the requirement to create the mental self-image in the audience of standing by the sea waiting, to really create that concept in someone’s mind. This requires a number of words longer than “stand by the sea and wait for a rubber ball to drift into view”.

Using handwriting rather than wall-sized cut vinyl letters reproduces the Johns/de Kooning power relationship in the form of an aesthetic relationship between the simple recording of an idea and Weiner’s increasingly grandiose and expensive typography. It evokes Weiner’s humble (but authentic…) beginnings and brings this into tension with the artworld monster he has become. This is a dialectical art, of aesthetic and conceptual tension and what they generate. Though it may seem to be more about the artworld than about geopolitics (as was the case in Art & Language’s Cold War-era “Portrait of Lenin In The Style Of Jackson Pollock”), the artworld and the careers within it are a reflection of broader socioeconomic changes.

Making an edition of photographs emphasizes the work as competent contemporary art given the increasing prevalence of editions in the art market. The contrast between the edition and the physical original draws in the economic and social relationships between the privileged individuals who pay for and experience the work itself and those of us who just see photographic records of it in galleries, books and magazines. The digital image is also Lawrence Weiner Erasure available on Flickr as a Creative Commons Attribution-Licenced download, making it Free Culture as well. This sits in further tension with the idea of an edition. And it is an important moral statement when making work by excercising one’s right to commentary on and reference or depiction of the work of previous artists, protecting the rights of future artists and critics to do so in turn.

Lawrence Weiner Erasure – a work of conceptual art

An erasure of Lawrence Weiner’s ‘A RUBBER BALL THROWN AT THE SEA’ 1969

Download/Print the photo: free, help yourself

Framed photos, limited edition of five (four currently available): £100 each

Drawing pad, with text and ballpoint pen: £750

Raushenberg and Weiner are two favourite artists of mine (although I can’t stand Rauschenberg’s comic strip panels). More to the point, they are well known within the artworld and their institutional histories are useful critical resources. “Lawrence Weiner Erasure” is an aesthetically and conceptually literate and effective mash-up of the form of Weiner’s art with the content of Rauschenberg’s that expresses an important critique of the history and experience of conceptual art.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.