Mainframe Experimentalism

Early Computing And The Foundations Of The Digital Arts

Edited by Hannah B Higgins and Douglas Kahn

University of California Press, 2012

ISBN 978-0-520-26838-8

The history of arts computing’s heroic age is a family affair in Hannah B Higgins and Douglas Kahn’s Mainframe Experimentalism. Starting with the founding legend of the FORTRAN programming workshops that one of the editors’ parents led in their New York apartment in the 60s, the book quickly broadens across continents and decades to cover the mainframe and minicomputer period of digital art. Several of the chapters are also written by children of the artists. Can they make the case that the work they grew up with is of wider interest and value?

The 1960s and 1970s were the era prior to the rise of home and micro computing, when small computers weighed as much as a fridge (before you added any peripherals to them) and large computers took up entire air conditioned offices. Mainframes cost millions of dollars, minicomputers tens of thousands at a time when the average weekly wage was closer to a hundred dollars. To access a computer you had to engage with the institutions that could afford to maintain them – large businesses and universities, and with their guardians – the programmers and system administrators who knew how to encode ideas as marks on punched cards for the computer to run.

Computers looked like unlikely tools or materials for art. The governmental, corporate and scientific associations of computers made them appear actively opposed to the individualistic and humanistic nature of mid-20th Century art. It took an imaginative leap to want to use, or to encourage others to use, computers in art making.

Flowchart for asking your boss for a raise, Georges Perec

Many people were unwilling or unable to make that leap. As Grant Taylor describes in The Soulless Usurper, “Almost any artistic endeavor(sic) associated with early computing elicited a negative, fearful, or indifferent response”(p.19). The idea, or the cognates, of computing were as powerful a force in culture as any access to actual computer hardware, a point that David Bellos makes with reference to the pataphysical bureaucratic dramas of Georges Perec’s Thinking Machines. Those wider cultural ideas, such as structuralism, could provide arts computing with the context that it sorely lacked in most people’s eyes as Edward A. Shanken argues in his discussion of the ideas behind Jack Burnham’s “Software” exhibition, an intellectual moment in urgent need of rediscovery and re-evaluation.

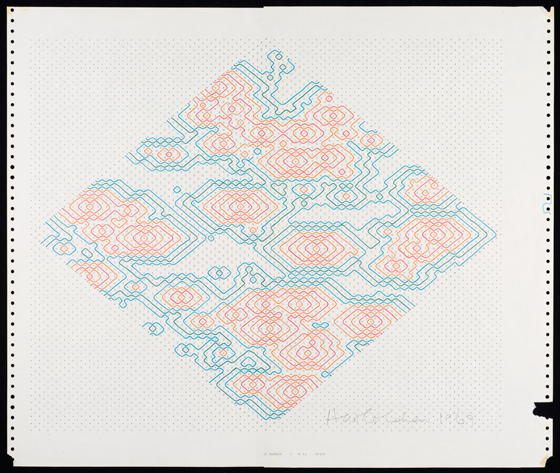

The extensive resources needed to access computing machinery led to clusters of activity around those institutions that could provide access to them. In Information Aesthetics and the Stuttgart School, Christoph Klütsch describes the emergence of a style and theory of art in that town (including work by Frieder Nake and Manfred Mohr) in the mid-1960s. In communist Yugoslavia the New Tendencies school at Zagreb achieved international reach with its publications and conferences as described by Margit Rosen.

Charlie Gere’s Minicomputer Experimentalism in the United Kingdom describes the institutional aftermath of the era that is the book’s focus. Like Gere I arrived at Middlesex University’s Centre For Electronic Arts in the 1990s with the knowledge that there was a long history of computer art making there. Also like Gere I encountered John Lansdowne in the hallways and regret not taking the opportunity to ask him more about his groundbreaking work.

Perhaps surprisingly, music was an early aesthetic and cultural success for arts computing. The mathematics of sound waveforms, or musical scores, were tractable to early computers that had been built to service military and engineering mathematical calculations. In James Tenney at Bell Labs, Douglas Kahn makes the case that “Text generation and digitally synthesized sound were the earliest computer processes adequate to the arts” (p.132) and argues convincingly for the genuine musical achievements of the composer’s work there. Branden W. Joseph places John Cage and Lejaren Hiller’s multimedia performance “HPSCHD”, made using the ILLIAC II mainframe, in the context of the aesthetics and the critical reactions of both, and considers how the experience may have influenced Cage’s later more authoritarian politics. Cristoph Cox, Robert A. Moog and Alvin Lucier all write about the latter’s “North American Time Capsule 1967”, a proto-glitch vocoder piece that, as someone who is not any kind of expert in that area, I didn’t feel warranted such extensive treatment.

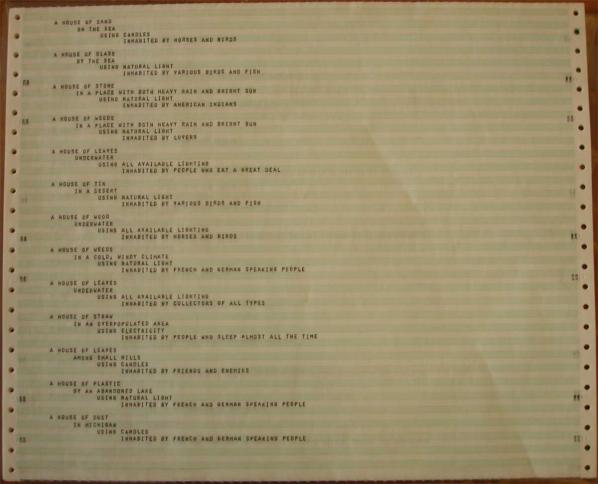

Hannah B Higgins provides An Introduction To Alison B Knowles’s House of Dust, describing it as “an early computerized poem”. It’s a good poem, later realized in physical architecture, and given extensive responses by students and other artists, that helps underwrite the claim for early arts computing’s cultural and aesthetic significance. Benjamin H.D. Buchlock describes the cultural and programmatic construction of the poem in The Book of the Future. And to jump ahead for a moment, a later extract from Dick Higgins’ 1968 pamphlet “Computers for the Arts” explains the programming techniques that programs like “House of Dust” used.

I mention this now because of the way that the extract of Higgins’ pamphlet contrasts with the version published in 1970 (available online as a PDF scan that I would urge anyone interested in the history of arts computing to find and study under academic fair use/dealing). Mainframe Experimentalism includes many wonderful examples of the output of programs, and many detailed descriptions of the construction of artworks. But the original of “Computers for the Arts” goes beyond this. It includes not just a description of the code techniques but a walk-through of the code and the actual FORTRAN IV program listings. Type these into a modern Fortran compiler and they will run (with a couple of extra compiler flags…). For all the strengths of Mainframe Experimentalism, it is this kind of incredibly rare primary source material that we also need access to, and it is a shame that where more was available it couldn’t be included.

Three Early Texts by Gustav Metzger on Computer Art collated by Simon Ford gives the reader a feel for the intellectual zeitgeist of arts computing at the turn of the 1970s, one that might surprise critics then and now with its political literacy and commitment. William Kazen brings Nam June Paik’s lesser known computer(rather than television)-based work to the foreground while tying it to the artist’s McLuhanish hopes for empowering global media.

Knowles’ poem isn’t in the section on poetry (it’s classified as Intermedia), which begins with Christopher Funkhouser’s First-Generation Poetry Generators: Establishing Foundations in Form. Funkhouser gives an excellent overview of the technologies and approaches used to create generative text in the mid 1960s, providing a wonderful selection of examples while tracking pecedents back through Mallarme to Roman times.

In Letter to Ann Noël Emmet Williams explains the process for creating a letter expanding poem that had been recreated on an IBM mainframe. Like “House of Dust” it’s an example of computer automation increasing the power of an existing technique for generating texts. Hannah B Higgins’ The Computational Word Works of Eric Andersen and Dick Higgins draws a line out of Fluxus for the artists’ Intermedia and computing work. Eric Andersen’s artist’s statement describing the lists of words and numbers used to create “Opus 1966” shows both the ingenuity and intellectual rigour that artists brought to bear on early code poetry. The inclusion of Staisey Divorski’s translation of Nanni Balestrini’s specification for “Tape Mark I” provides an example of the depth of appreciation that prepraratory sources can provide for an artwork. Mordecai-Mark Mac Low describes how his father took ideas from Zen Buddhism and negotiated the technial limitations of late 1960s computing machinery to realise them in poetic form in The Role of the Machine in the Experiment of Egoless Poetry: Jackson Mac Low and the Programmable Film Reader.

Finally, Mainframe Experimentalism turns to cinema. Gloria Sutton casts Stan VanDerBeek’s “Poemfields” in a more computational light than their usual place in media history as experimental films to be projected in the artist’s MovieDrome dome. Ending where a history of the ideas and technology of arts computing might otherwise begin, Zabet Patterson describes the triumphs and frustrations of using World War II surplus analogue computers to make films in From The Gun Controller To The Mandala: The Cybernetic Cinema of John and James Whitney. It’s a fitting finish that feels like it brings the book full circle.

I mentioned that several of the essays in Mainframe Experimentalism were written by family members of the artists. A number of the essays also overlap with their coverage of different artists, or describe encounters or influences between them. Arts computing was a small world, a genuine avant-garde. We are lucky not to have lost all memory of it, and we should be grateful to those students and family members who have kept those memories alive.

In “Computers For The Arts”, Dick Higgins describes two ways of generating output from a computer program – aleatory (randomized) or non-aleatory (iterative) ways. Christopher Funkhouser and Hannah B Higgins’s essays also touch on this difference, but forty years later. This is key to understanding computer art making not just in the mainframe era but today. Computers are good for describing mathematical spaces then exploring them step by step or (psuedo-)randomly, and whether it’s an animated GIF or a social media bot you can often see which of those processes is at work. It’s inspiring to see such fundamental and lasting principles identified and made explicit so early on.

Away from the era of the “Two Cultures” of science and the humanities, and of computing’s guilt by association with the database-driven Vietnam War, the art of Mainframe Experimentalism rewards consideration as a legitimate and valuable part of art history. Not all of it equally, and not all of it to the same degree – but that is true of all art, and cannot be used to disregard early arts computing as a whole. This aesthetically and intellectually under-appreciated moment in Twentieth Century art is crying out for a critical re-evaluation and an art historical recuperation. Mainframe Experimentalism provides ample examples of where we can start looking, and exactly why we should.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

White Heat Cold Logic

British Computer Art 1960-1980

Edited by Pal Brown, Charlie Gere, Nicholas Lambert and Catherine Mason

ISBN 9780262026536

MIT Press 2008

This is the third and last in a series of reviews of the results of the CACHe project. The first review was of the V&A’s show and book “Digital Pioneers“, the second was of Catherine Mason’s “A Computer In The Art Room”. Where “A Computer In The Art Room” concentrated on the history of art computing in British educational institutions up to 1980, “White Heat Cold Logic” gives voice to the individuals who made art using computers in that period more generally.

Charlie Gere’s introduction explains the source of the book’s title, referring to the British Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s famous 1963 speech that a new Britain would be forged in the white heat of the scientific and technological revolution. Gere provides an overview of the history of art computing in the era that may be familiar from “A Computer In The Art Room” which is much needed, for it provides useful context for what follows in this volume. He also argues for the value and interest of the history of art computing, in terms that make it clear for academia.

Roy Ascott describes the emergence of pre-computational art informed by cybernetics, systems theory and process against the background of the emergence of “Grounds Course” art education. Adrian Glew documents Stephen Willats’ use of computing in the processes of his art of cybernetic social engagement, the first but not the last more mainstream British artist to appear. John Hamilton Frazer describes the unrealised interactive architecture of the 1960s “Fun Palace” and 1980s “Generator” and of the technology and social legacies of these nonetheless influential projects.

Maria Fernandez puts the figure of Gordon Pask centre stage. As John Lansdown (to whom this book is dedicated) emerged as a major figure behind educational arts computing in “A Computer In The Art Room”. Gordon Pask also emerges in this volume as the cybernetic prophet of the 1960s, mentioned by many in the early essays in this book. His own interactive theatre and robotic mobiles complement his involvement in planning the Fun Palace and as a source of ideas and support for more projects.

Jasia Reichardt provides a theoretical and practical insight into the genesis of her foundational “Cybernetic Serendipity” show at the ICA in 1968 and considers what came next. Brent Macgregor provides an outside view of the same. Neither attempts to mythologize this much mythologized show, the reality of its achievements is more than impressive enough.

Edward Ihnatowicz is the subject of two essays, one with tantalising images of preparatory and documentary material by Aleksandar Zivanovic and an insightful but more personal essay by Richard Ihnatowicz. Hopefully his reputation will continue to increase towards the level it deserves.

Richard Wright follows the ideas of Constructivist art into Systems Theory, which alongside cybernetics is one of the guiding ideas of the art of the period overdue for rediscovery both within art computing and more generally.

Harold Cohen remembers the origins of his “AARON” painting program in a tale of the struggle of art against bureaucracy. Tony Logson’s tale is surprisingly similar, although his systems-based art is very different from Cohen’s cognitively-inspired forms. Simon Ford reveals Gustav Metzger’s involvement with early computer art and with the Computer Arts Society (CAS). CAS also feature large in Alan Sutcliffe’s description of his computer music compositions, one of many essays that left me wishing I could see the code and experience the art as well as reading about it.

George Mallen also touches on CAS, and on Pask’s System Research Ltd. as he explains the art and business of the production of the unprecedented environmentalist interactive multimedia of the “Ecogame”. The Ecogame is one of many works in the book that people simply need to know about. Doron D. Swade makes the idea of the “two cultures” of art and technology that came together for the Ecogame more explicit in an attempt to recover the art of the Science Museum’s first computing exhibit.

Malcolm le Grice and Stan Heyward each describe the institutional travails of making some of the first computer animation in the UK. Catherine Mason draws together the history of many of the institutions already mentioned in what is both a recap and an extension of the history she presented in “A Computer In the Art Room”. Stephen Bury and Paul Brown bring the influence of the Slade to the fore in their chapters, revealing the Slade as an important piece in the puzzle of British Computer Art.

Stephen Scrivener, Stephen Bell, Ernest Edmonds and Jeremy Gardiner each describe their personal artistic journeys through the era of FORTRAN and flatbed plotting, illustrated by images of their work that again made me wish I could also see the code. Graham Howard describes how conceptual artists Art & Language didn’t use a university computer to generate the 64,000 permutations of one of their “Index” projects of the 1970s, instead gaining access to a local produce distribution company’s mainframe across several weekends.

The different strands of technology, institutions, ideas and economics are all drawn together in John Vince’s history of the PICASO graphics library, which spread from Middlesex Polytechnic to many other educational institutions and the successor to which, PRISM, was used to make the first logo for Channel 4.

Brian Reffin Smith makes clear, artists were as affected by the idea of computing as by computers themselves, especially when they didn’t have access to them. The Fun Palace was influential despite never being realized, Senster was influential despite being lost. It is important to realize just how limited access to computing machinery was in the era covered by the book, and to recognize how ideas of computing and its potential were part of the broader intellectual environment of the time.

Finally, Beryl Graham’s postscript covers the history of UK arts computing after 1980. I lived through some of the period covered and I recognise Graham’s description of it. The critical irony that she identifies in UK net.art and interactive multimedia is of key importance to its art historical value. Although I would question how uniquely British this is, the UK certainly took it as a baseline. As with Gere’s introduction, Graham presents the case for art computing in a way that the art critical mainstream should not just be able to understand but should be inspired by. Cybernetics, systems theory, environmentalism, socialisation, the content of conceptual art, and the political concerns and developments of the Cold War all illuminate and are in turn illuminated by this history.

For a book about art computing it is frustrating how little art and source code is illustrated in the book. Much work has been lost of course, and “Digital Pioneers” does illustrate art from this period. But for preservation, criticism and artistic progress (and I do mean progress) it is vital that as much code as possible is found and published under a Free Software licence (the GPL). Students of art computing can learn a lot from the history of their medium despite the rate at which the hardware and software used to create it may change, and code is an important part of that.

White Heat, Cold Logic presents hard-won knowledge to be learnt from and built on, achievements to be recognised, and art to be appreciated. Often from the people who actually made it. What was previously the secret history or parallel universe of art computing can now be seen in context alongside the other avant-garde art movements of the mid-late 20th century. I cannot over-emphasise the service that CACHe has done the art computing community and the arts more generally by providing this much needed reappraisal of early arts computing in the UK.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

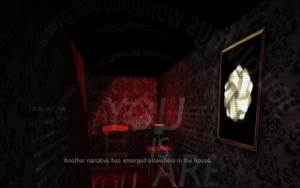

Featured image: Nightingale’s Playground Chapter Selection

Andy Campbell is a UK writer who has been experimenting with new media fiction since the 1990s, when he started creating stories on floppy disc for the Commodore Amiga. By 2000, when I first came across him, he was working mainly in Flash and self-publishing the results on a website called “Digital Fiction”. He has continued to produce one or two pieces of work per year ever since, latterly on a site called “Dreaming Methods”. His output is invariably enigmatic, complex, densely-textured, dark in tone and technically highly-accomplished; and he has gradually established himself, certainly amongst his peers, as one of the leading exponents of the digital fiction form.

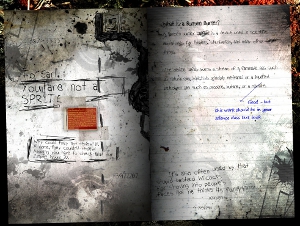

His most recent work is also his biggest and most ambitious to date. Entitled Nightingale’s Playground, it consists of four interlinked parts: a click-and-read interactive story; a 3D “game”, which involves exploring a dark flat; a virtual exercise-book, the pages of which can be turned by dragging them across the screen with your mouse; and an ebook text narrative, written in short fragments.

The story, put simply, goes like this. In “Consensus Trance” (the click-and-read interactive section), the adult Carl has just broken up with his girlfriend. The one item he carries away from the breakup is an old red vanity case belonging to his Gran, with whom he used to live when he was a boy. The case contains bits of talismanic bric-a-brac dating back to Carl’s schooldays. Partly because the contents of the case have jogged his memories, Carl attends a school reunion in the hope of catching up with his best schoolfriend, Alex Nightingale. But Alex isn’t there – and furthermore nobody else can remember him. Carl remembers that Alex disappeared unaccountably while he was still at school. He begins to wonder whether Alex actually existed at all, or whether he imagined him; but at the same time he starts to feel as if “ordinary life” might be the illusion, and Alex might have disappeared because he somehow managed to get through to a further reality. He goes back to revisit the flat where Alex used to live.

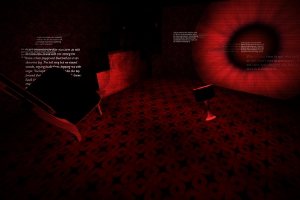

“Consensus Trance II” picks up from inside the flat’s front door. It takes the form of a 3D “game”, in which we must walk through the passages and rooms of a half-dark flat, discovering fragments of white text as we go, and unlocking extra sections of the flat once a certain number of texts have been discovered. The text-fragments reprise parts of the story which can be found elsewhere, but they also develop the theme that Alex may have disappeared because he managed to get beyond the illusion of everyday life, along with a suggestion that Carl and Alex may be figments of one another’s imagination (many of the text-fragments have Alex’s name in them at one moment and Carl’s at the next), and a third idea that Carl may not be able to remember what happened to Alex because it was something so terrible that he blocked it out of his mind. In the last room of the flat, which has to be unlocked by discovering and “walking through” all the text-fragments elsewhere, this suggestion becomes more concrete: Alex may have tested out his own theories about reality by drinking something poisonous, and therefore he may have disappeared because he killed himself. The process of exploring the half-dark flat thus becomes a metaphor for Carl’s exploration of his own repressed memories, and the fragmentary revelation which awaits us in the last room represents the moment in which he rediscovers his personal nightmare.

The third part of the story, “The Fieldwork Book”, is an old exercise book of Alex’s – or rather a virtual exercise book, apparently recently dug-up, complete with soil-stains, scribbly handwriting, comments in blue from the teacher, doodles, bits of leaf stuck to the pages with sellotape, and woodlice running around on the front cover. It contains the beginnings of a school project about nature – “A dead tree may look lifeless, but actually it’s teeming with activity…” – along with notes from Alex to Carl – “Worthington has paired me up with this mad girl called Joanne. She smokes and stinks but I quite like her.” – and a lot of press cuttings and comments about a computer-game called The Sentinel. All of this makes more sense once the other parts of “Nightingale’s Playground” have been visited, particularly the ebook, which gives a lot of background information about both the Fieldwork Book itself and the Sentinel.

One thing we learn from the ebook section of the story is that The Fieldwork Book is a kind of changeling. Carl buried his science exercise book in the back garden behind his gran’s flat, at Alex’s suggestion, as a way of making it look more grubby and out-of-doors, and thus suggesting to the science teacher that it had been used intensively in the development of the nature project. However, when he dug it up again after Alex’s disappearance, what he discovered was not his own exercise-book but one belonging to Alex.

Another thing we learn is that The Sentinel, to which the Fieldwork Book makes numerous references, is an old Commodore computer-game with which Alex was obsessed. It had 10,000 levels, all based on the same principle: that players had to approach an object called The Sentinel across mountainous terrain without being observed. If they were detected the game would be over. Carl never managed to get very far but Alex managed to get to level 9,999 – and in fact one possible explanation for his disappearance is that it may have had something to do with him reaching level 10,000. He and Carl also played their own outdoor version of The Sentinel, in which Carl would have to stand still while Alex attempted to creep up on him undetected. A copy of The Sentinel is one of the items of bric-a-brac which Carl the adult discovers in his Gran’s old red vanity case.

The ebook also gives some more information about the vanity case itself. When Carl retrieves the Fieldwork Book and finds it to be Alex’s version rather than his own, he hides it in his Gran’s sideboard, and whilst hiding it he discovers something else in there – the red vanity case. The story doesn’t actually tell us in so many words that he looks inside the case, but we gather he must have done, because later on he has a conversation with his Gran, who is telling him that the contents of the case are private and he mustn’t look in there again:

“But what’s that red case? What are those papers?”

“They’re nothing,” she said insistently. “They’re from a long time ago, they don’t make any sense and they’re private love, they’re just private.”

The papers may have something to do with Alex’s death. On the other hand, they may be connected with Carl’s mother, since this is one of the few times in the story when she gets a mention:

…[Gran said] there were things in the world, happenings, that she didn’t understand, and neither would I, and neither would anyone else, and sometimes it was best to just leave them alone.

“Like we leave Mum alone,” I murmured. She didn’t answer that, and looked a little hurt, so I whispered “sorry” and she started talking to me again…

These hints are never developed further.

Nightingale’s Playground is not without its shortcomings. Its most obvious structural weakness is that its four different sections are in four different formats, each with its own distinctive “look” in terms of graphic design, and each needing to be viewed and interacted with in a different way. This is asking a lot of any readers and viewers who are unfamiliar with new media, although it’s actually less of a problem than might be supposed. Once the initial leap of faith has been made the cross-references between the four sections soon start to pull the story together into a surprisingly cohesive single structure. All the same, the fact that two parts are designed to be viewed online, whereas the other two parts are designed to be downloaded onto your own computer (or ereader) does make it a little bit inconvenient to shuttle backwards and forwards between one section and another if you want to examine the story in detail.

A more serious flaw is the fact that the Fieldwork Book doesn’t actually add very much to our sense of what’s going on. Pretty much all the information it contains (about the Sentinel, and Alex’s view of reality) can be garnered from the other sections, and although reading the Fieldwork Book gives us a slightly stronger sense of Alex’s personality and voice, the material in it begins to seem rather like padding on repeated viewing. There is a similar problem with the red vanity case, which is built up into something of great importance both in the point-and-click narrative section of the story and the ebook. When we actually get to see what’s inside the vanity case, halfway through the point-and-click section, the contents turn out to be rather disappointing.

Campbell does tend to talk up the importance of events and symbolic objects in his stories, rather than leave them to speak for themselves, which can sometimes backfire and lead to a sense of anticlimax. His prose-style can be overblown, a trait which is probably at its most noticeable in the “game” section of the story, where white texts either hang in the air or in some cases appear on the walls of the darkened flat. Some of these texts are particularly sonorous and doomy:

Where were we? Who were we? How much control did we have over the rain coming down, the hideous blank backdrop we were cut and pasted and glued against?

You were onto it, like you were onto something that meant all of this was wrong, some kind of mad illusion; that there was a staggering, amazing psychedelic hope going on that I desperately, weepingly wanted to understand.

I get the feeling everything changed then, like you said words to me that didn’t exist; a language that spoke the impossible; couldn’t be absorbed by the normal brain. Did you even invent some new words? Pierce a new crack in the fabric of what was going on in our limited, messed up world?

“The hideous blank backgrop”; “mad illusion”; “staggering, amazing psychedelic hope”; “desperately, weepingly wanted to understand”; “pierce a new crack in the fabric of what was going on” – the harder these phrases try to impress us, the less they succeed. The trouble is that there isn’t enough concrete observation or information here to convince us that the big emotive adjectives are justified. They seem to be flapping around in a vaccuum.

On the other hand, the ebook section of Nightingale’s Playground contains some of Campbell’s tightest and most effective writing:

Science was my best lesson because Alex was in it – science without Alex was a shitty prospect. I didn’t like any of the other kids in the class, I didn’t like the teacher, I didn’t like doing experiments or doing any work. Science for me was about swapping computer game cassettes under the table, scribbling rude shapes on Alex’s excercise book, whispering about whether the teachers were really aliens trying to brainwash us or whether the entire school was some kind of hologram that folded up and disappeared after the bell for hometime.

This is both convincing about the boredom of being a schoolkid in a dull lesson, and suggestive in terms of the story’s wider themes – the idea that “the entire school was some kind of hologram” clearly links to the alternative-reality theme. The ebook as a whole is written in short punchy sections jumbled into a non-linear sequence, shuttling us backwards and forwards through a term of so or Carl’s school memories, and unfolding (without ever fully explaining) the story of Alex’s disappearance. It works as a stand-alone, but it also works as the glue which holds the entire structure of Nightingale’s Playground together.

It should also be said that although the flat-exploring section of the story is sometimes overwritten, it is also the most thoroughly immersive of all four parts, and the one where Campbell’s characteristic approach to new media fiction comes into its own most strongly. He has always been at pains not to place his text in front of his images, or beneath them or to one side, like labels on tanks at the zoo or explanatory plaques next to pictures in a gallery; instead he puts his words inside his graphical environments, sometimes hidden or partially-hidden inside them, so that we have to explore to read. This avoids the danger of us regarding the texts as more important than the images. It pulls us in, and it makes his work inherently immersive and interactive.

This characteristic technique is taken a step further in the flat-exploring section of Nightingale’s Playground (which was built with gaming software called Coppercube 2.0), because here the three-dimensional space is deeper, more mazelike and more thoroughly-articulated than Campbell’s customary Flash environments. There is a sinister audio track which changes incrementally as we move from one part of the flat to another, enhancing our sense of three-dimensionality (the audio dimension of Campbell’s environments should not be overlooked in any of his work). The atmosphere is claustrophobic and scary. When you manage to find the right number of texts to unlock an extra section of the flat, there is a loud door-latch click which makes you jump even if you’re expecting it. When you get to the last room of the flat – the one where Carl is starting to get fragmentary recall of Alex’s possible suicide – the space is suddenly bigger, the predominant colour is red, there are items of furniture floating in the middle of the air, the far wall is decorated with a massive staring eye (an icon from the Sentinel game), the text-fragments tend to slide around in front of you as you approach them instead of staying still, and the whole effect is genuinely climactic and nightmarish. There can be no doubt that at moments like this Nightingale’s Playground is an extremely effective piece of new meda fiction.

It’s interesting to note how closely the climax of this flat-exploring sequence resembles Grandma’s house in Tale of Tales’ horror-game The Path. Campbell is an admirer of Tale of Tales’ work, but he hadn’t seen The Path prior to the completion of Nightingale’s Playground. All the same, the parallels are striking: the feeling of combined claustrophobia and disorientation, the sinister red-and-black colouring, the way the reader/viewer is barraged with suggestive fragments, and the way this technique is used to suggest flashbacks. There is a strong sexual theme in The Path which is not present in Nightingale’s Playground, but otherwise it’s difficult to escape the feeling that both Campbell and Tale of Tales have seized upon the exploration of a mazelike game-space as a metaphor for an inner journey, and have developed the metaphor in very similar ways.

Readers who are familiar with Campbell’s earlier work will recognise a number of the themes and motifs employed in Nightingale’s Playground. The Fieldwork Book, for example, is designed in very much the same way as an earlier virtual exercise book from a story called “The Scrapbook”; collections of fragmentary jottings, or old half-corrupted electronic files, can also be found in “Fractured”, “Floppy” and “The Incomplete”; the feverish boy being looked after by his Gran, with his mother either absent or not interested, is a familiar figure from “Dim O’Gauble”; the schoolfriend who introduces the first-person narrator to an apocalyptic secret is an echo of “Capped”; and a gloomy flat which must be explored for clues to the story’s central mystery can also be found in “The Flat”.

But these narrative strategies in turn suggest certain deeper patterns on which much of Campbell’s work seems to be built. His abiding interest in hints and fragments, for example, is admittedly suited to the nonlinear style of new media literature, but it also serves to suggest that Campbell’s central characters are often living in a reality with two layers: the “ordinary” everyday world which is mean, dull, shoddy and constricting, but relatively safe; and an inner or underlying reality which can only be glimpsed rather than viewed as a whole, possibly because it is so dangerous and frightening – a reality which emerges fitfully via dreams, games, imaginings and doodles.

It also frequently the case in Campbell’s work that the constricted dullness of the “ordinary” world is associated with adult life and adult sensibilities, whereas the “inner” reality is associated with childhood. Thus, in Nightingale’s Playground, the adult narrator starts to rediscover his “real” self when he breaks up with his girlfriend and rediscovers his memories of his best friend Alex. In a way, this could be seen as a Romantic or Wordsworthian view of the relationship between childhood and adulthood: as children we are much more in touch both with our imaginations and our inner selves, and therefore much more aware of the true nature of things, while as adults we become more absorbed in “getting and spending”, and therefore spiritually dull. Campbell is certainly no sentimentalist about childhood – in fact his stories are full of instances of kids being nasty to each other – and it should also be noted that the imaginative insights of the children in his stories may be shared or partially shared by more elderly figures such as the Gran in Nightingale’s Playground, another Gran in Dim O’Gauble, and the dying old man in Last Dream. It may be that these old people share the visionary capabilities of the young by virtue of their closeness to death – there are strong hints in the ebook section of Nightingale’s Playground that Carl’s Nan is about to die of lung cancer.

Perhaps a better literary antecedent for Cambell’s obsessive and visionary kids is the figure of Roland from Alan Garner’s Elidor – another hypersensitive and super-visionary outsider whose insight and talents serve to isolate him both from the mundane world of the Manchester suburb where he lives, and from the other members of his own family who would rather have safe, dull lives than dangerous, eccentric and magical ones. Of course Roland is an outsider-figure who can easily be identified with Alan Garner himself; and in the same way, Alex Nightingale can easily be identified with Campbell. The refusal of these visionary characters to settle for mere ordinary life can be interpreted as an oblique declaration of intent from the artists who created them. But there are other messages here too. The whole structure of Nightingale’s Playground is telling us something about the nature of the world we live in. Did Alex Nightingale actually disappear into an alternative reality, or did he commit suicide? Did Carl imagine Alex, did Alex imagine Carl, or did they both somehow imagine each other? Is the Sentinel just a computer-game or the key to something deeper? What was in the red vanity case when Carl first discovered it? What is the secret his Gran is so anxious to keep hidden? The fact that all of these issues are left hanging, and that the whole pattern of the story is therefore deliberately-unresolved, ambiguous, is a message in itself. Life isn’t clear-cut: it isn’t about answers: it’s about questions.

Nightingale’s Playground has its shortcomings, but it builds Campbell’s open-ended style of narrative into a more ambitious and absorbing structure – and explores some of his characteristic themes with greater maturity and depth – than anything he has produced before.

This review is co-published by The Hyperliterature Exchange and Furtherfield.org.

A Computer in the Art Room: The Origins of British Computer Arts 1950-1980

Catherine Mason

ISBN: 1899163891

JJG Publishing 2008

Computing anywhere else but its history often seems like a carefully guarded secret. This has been alleviated by activity around the resurrected Computer Arts Society in the 2000s, notably the acquisition of CAS’s archives by the V&A and the CaCHE project at Birbeck College which ran from 2002-2005. CaCHE, run by Paul Brown, Charlie Gere, Nick Lambert and Catherine Mason, produced conferences, exhibitions, and publications including the book “A Computer In the Art Room”, by Mason.

The art room of the title is the art department of British educational institutions prior to art becoming a degree-level subject. From the 1950s to the 1970s, when the cost of computing machinery dropped from the level where only major government and corporate organizations could afford them to the level where you only needed a second mortgage to afford one, the best way for artists to get access to the enabling technology of computing machinery was usually in an educational institution.

Mason starts out by describing the artistic and art educational situation in the UK at the time of the Festival Of Britain and the foundation of the ICA in London in the early 1950s. She then explains the structure and significance of the emergence of Basic Design teaching, the impact of the Coldstream report on art education, and the rise of the polytechnic colleges over the next thirty years. This provides vital context for the emergence of art computing teaching in the UK. It is also of more general interest for British art history. Conceptualism, performance, Land Art, the Hornsey Art School occupation, and the educational and media graphics that are currently being used as the basis of “hauntological” art all share this background and can better be understood and critiqued with better knowledge of it.

Basic Design courses started in London but didn’t remain there for long. They spread and matured throughout the UK, becoming entangled with the earliest teaching of art computing in provincial technical colleges. Mason traces the family trees of art computing teaching over time through these institutions and back to London-based institutions. Some of the names are familiar from art history (Richard Hamilton, Stephen Willats), some from art computing history (Harold Cohen, John Latham). Where the people involved cross over with cybernetic art, Conceptualism or other artistic currents Mason shows how their ideas fed into and from their art computing work.

The conceptual content of art computing followed the Bauhaus, cybernetics, systems, sociological and environmental influences on art from the 1950s to the 1970s. Its technological forms likewise followed those of mainstream computing. In the 1960s time was leased on mainframes or computers were built by hand. In the 1970s, minicomputers became available and art domain-specific software frameworks or programming languages were written by their users. In the 1980s, workstations with touch tablets, framebuffers, and increasingly proprietary software brought previously unprecedented power and ease of use at the cost of more fixed forms.

The history that I had to piece together as a student from hearsay and from hints in old publications, of the PICASO graphics language at Middlesex University that I found a print-out of the manual for when I was there in the 1990s, of Art & Language’s use of mainframe computers, of early cross-overs between art computing and dance, of cybernetic systems and games that attracted mass audiences before disappearing, is detailed, illustrated and contextualized in page after page of descriptions of hardware, software, institutions, courses and projects. The detail would be overwhelming where it not for Mason’s ability to bring the human and broader cultural aspect of it all to life.

There’s Jasia Reichardt’s Cybernetic Serendipity show at the ICA, Andy Inakhowitz’s Senster robot, John Latham’s dance notation experiments, The Environment Game, and computer graphics drawn with the languages and environments developed in UK art institutions. There’s pictures of the computer systems at the Slade, the RCA, Wimbledon and other art schools that serve as insights into the artists’ studios. There’s the Computer Arts Society, IRAT, APG. And, crucially, there’s the links between them told in a narrative that is coherent while still presenting the breaks and false starts in the story.

The history of “A Computer In The Art Room” reads all too often as brief moments of individuals triumphing against the odds to produce key works of art computing then fading into obscurity, academia or commerce. But any art history that considers a specific context at such a level of detail will look like this. Mason describes works, institutions and artists that deserve broader recognition, although she is under no illusion about how far the road to that recognition may be, citing the example of how long it has taken for photography to be recognized as art in the culturally conservative UK.

The social and pedagogical changes of the period covered by “A Computer In The Art Room” reflect a time of hope and ambition for education in society that made the academy less remote. Mason provides the social, technological and educational context needed to appreciate the very real achievements of art computing that she describes against this backdrop. As a slice of art history this is richly detailed. It touches on subjects far beyond art computing that will help any art student of history better understand the period covered. And it is both a relief and an inspiration to finally have a public record of this important aspect of the history of art computing in the UK.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

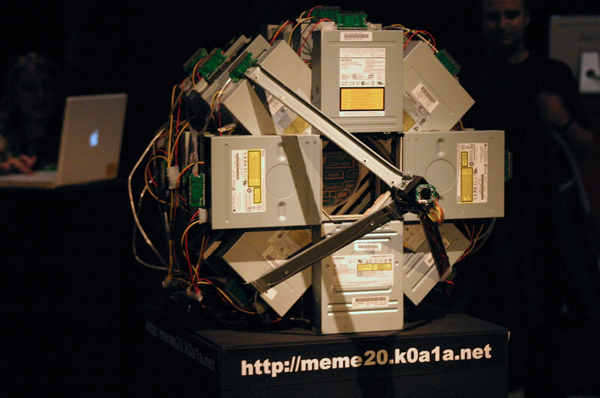

Danja Vasiliev will be working as an Artist in Residence at HTTP, Furtherfield’s Gallery and lab space in March 2010. During this residency Danja will work on his Netless project. Netless is an attempt to create a new network, alternative to the internet. More precisely – networks within existing city infrastructures, possibly interconnected into a larger network alike the internet. Netless is not dependent on specialized data carriers such as cables or regulated radio channels. In fact, there is no permanent connection between all of its hosts (peers) at all – it is net-less.

The network is based on the city transportation grid, where traffic of the vehicles is the data carrier. Borrowing the principals of the ‘sneaker-net’ concept, the information storage devices are physically moved from point A to point B. Numerous nodes of the netless network are attached to city buses and trams. Whenever those vehicles pass by one another a short range wireless communication session is established among the approaching nodes and the data they contain is synchronized. Spreading like a virus, from one node to another, the data is penetrating from the suburbs into the city and backwards, expanding all over the area in the meanwhile. The signal of any of netless nodes can be received and sent to using any wifi enabled device – a laptop, pda or mobile phone.

There are no addresses or routes in the netless network – any participant can potentially receive all data circulating in the network – all data is broadcast. Personal messages and datagrams can be sent using pgp-like personalized keys which ensure that only two people (the original sender and intended receiver) can decipher the message. Only such, as it might seem, oversimplified approach for communication allows the network to be completely homogeneous and flat – any node can be replaced by any other without any modification or configuration. In such an environment it is also impossible to trace data flows.

2006-2008: MA in Networked Media (Media Design) at Piet Zwart Institute, Netherlands

2006-2003: BA in ‘Media art’ AKI Academy of Visual Art and Design, Netherlands

2000-2001: Institute ‘ProArte’, short course of new media arts, Saint-Petersburg, Russia

1996-1999: Academy of Culture and Art, Media and Information Design, Saint-Petersburg, Russia

Danja Vasiliev is a co-founder of moddr_lab – http://moddr.net/.