An Interview with Julian Oliver By Taina Bucher.

I met the Berlin-based media artist and programmer Julian Oliver in Toronto as part of the Subtle Technologies festival, where he taught a workshop on the Network as Material. The aim of the workshop reflects Oliver’s artistic and pedagogical philosophy nicely; to not only make people aware of the hidden technical infrastructures of everyday life but to also provide people with tools to interrogate these constructed and governed public spaces.

Julian Oliver, born in New Zealand (anyone who has seen him give a talk will know not to mistake him for an Australian) is not only an extremely well versed programmer but is increasingly as equally knowledgeable with computer hardware. His background is as diverse as the places he has lived and the journeys it has taken him on. Julian started out with architecture but became increasingly interested in electronic art after working as Stelarc’s assistant on ‘Ping Body’, Auckland,1996. He moved on to Melbourne, Australia, and worked as guest researcher at a Virtual Reality center. Later he established the artistic game-development collective Select Parks and in 2003 left for Gotland to work at the Interactive Institute of Sweden’s game lab. He then moved on to Madrid where he had extensive involvement with the Media Lab Prado. Several countries, projects and residencies later, he made Berlin his preferred base, setting up a studio there with colleagues. Julian is also an outspoken advocate of free software and thinks of his artistic practice not so much as art but more in terms of being a ‘critical engineer’, a term that he applies particularly to his collaborations with his studio partner Danja Vasiliev.

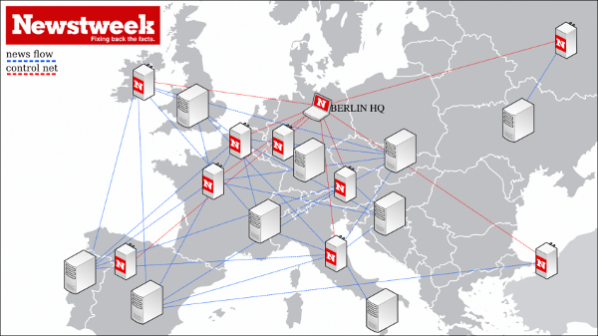

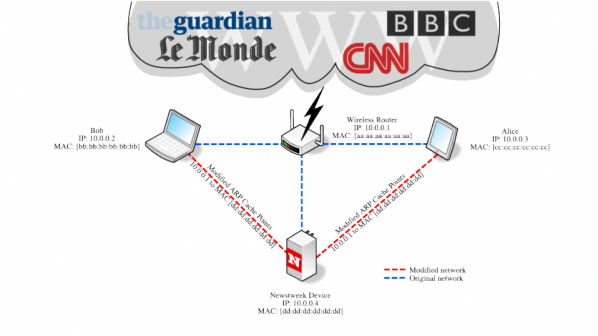

Their latest collaboration called Newstweek, was recently announced as winners of the Golden Nica in the Interactive art category of the Prix Ars Electronica 2011. The project leverages on the network as a medium for rigorous, creative investigation, exploring the intersection between the perceived trustworthiness of mass media and the conditions of networked insecurity.

His artistic practice clearly reflects his hacker and gaming background, playing around and messing with routers, capturing data from open wireless networks, visually augmenting commercial billboards in the cityscape, sonifying Facebook chats, visualizing protocols and otherwise manipulating networks for artistic purposes. I sat down with Julian on June 1st to talk about his most recent art projects, his reflections on software and digital media arts more generally. The interview was transcribed from a voice recording in a busy cafe to the best of my ability.

Taina Bucher: You started out with architecture and then moved over to games. How did that transition come about?

Julian Oliver: I realized quite early on that I was less interested in buildings than I was in exploring architecture in the context of the language within which it operates. I was more interested in hypothetical architecture. Like impossible structures such as what Buckminster Fuller proposed, and when I ended up working in a virtual reality centre in Melbourne I found that sitting behind a bunch of SGI machines dedicated to rendering virtual experiences, that I no longer really needed to invest in the idea to build something. I was more interested in something more plastic and mutable. The bridge from there to games came about around 1997-1998. Source code from games started to become available and it became apparent to me that it was possible to modify these games to explore an artistic practice, an architectural and sculptural practice really, using the medium of computer games. There were only 4-5 of us in the world working on this and we quickly made contact with each other. I left the VR centre and started an artistic game based modification lab in Melbourne called Select Parks. For about six years we did a whole bunch of projects based on computer games. We also established an online archive of the ever-increasing experiments and artistic investigations into computer game technology under selectparks.net. The archive is still there now.

TB: Was it the same interest in the mutability of the medium that led you to work with software more generally?

JO: I’ve been programming since I was pretty young and I’ve been around computers since I was a boy and working with them, but it was when I started to increase my freedom of movement with the medium of computer games that I became a programmer. I started to learn C, C++ and scripting languages and I quickly became hooked with the mix between technical challenges and rigorous creative exploration. I think the balance of the two still remains in my work.

TB: In one of your academic papers on games you ask the question of how much of the medium, as a raw field of possibilities, really is available to the artist. Well, let me ask you the same question in relation to software given that software always comes with a certain kind of aesthetic expectation.

JO: Definitely. I think it is a bit of a shame that much of what is called digital art is in fact made by using software suits built by large corporations. Macromedia, now the Adobe suite, is almost an infrastructure of the media arts. Painters of 200 years ago would never have accepted this brand attached to their canvas. They would never have accepted that their tools would be designed with such a generic mass audience in mind. I think that while the digital arts are certainly an exciting field there is an unadmitted dependency on a food chain that comes entirely from a corporation. The contemporary artist would then talk about breaking these tools, or you know, misusing them. But who is really holding the power? I think at a certain point for me, this was the reason why I moved entirely into free software. I really wanted to look at software as a core medium itself and I wanted to get at the guts of it. I wanted to have a rigorous personal relationship with technology so that I could bend it to my needs rather than my needs being bent.

TB: How do you picture a genuinely critical media arts practice then, moving away from the Adobe suites of the world?

JO: No, I think it is fine to use Adobe if it satisfies your expectations. However I think that the expectations themselves are already defined by these external corporate market inputs. I think it is really important for digital artists to understand what digits are. They call themselves software artists but they do not really write software or know what it is. By using it their works become symptomatic of a process that they themselves have not defined.

TB: Does this mean we have to know code in order to be critical of code?

JO: Yes. I think you need to speak the language. It is the same thing with other cultural practices; you need to know the basics of how a violin or a guitar works before you can pass a judgement on the player. There is a parallel history to the new media arts that is not written and that’s all of those technical and cultural contributions that artists and technologists make when they are producing a work of new media. There is certainly a very well written history for the work of art in the galleries but there is nothing of the sorts for the fundaments of the technical achievements. I mean we have that with music for instance, with the evolution of the piano, but there are things happening in the new media arts all the time that no one other than the technologists can really appreciate. These are significant contributions that actually shape the way in which media are used in the future. This is certainly the case with the development of a new programming language that a historian might not necessarily notice. A language like Python or a framework like open frameworks has shifted media arts in such an influential way. Most people only see the end product. Understanding just a little in this regard is enough for enriching the history of the field I think.

TB: One could certainly argue that the ‘democratization of code’ with web 2.0 technologies and open APIs potentially lets anyone produce software art?

JO: Yes certainly. Take Processing for instance, anyone can make a digital square if they want. There is nothing inherently wrong with that. What I am interested in is to make people understand what’s behind it. I think we as artists need to describe what we do and part of this is to publish the source code. For me personally this is an obligation. By publishing the source code I am enriching the scene by allowing other people to have an insight into how it works. Take the project that Danja and I have been doing with Newstweek. If we would hide the way it works it would not enrich anything. We’d only be contributing to our own careers. We therefore publish all our code. You can download it now and already be learning how we did it and so together as a whole we move forward.

TB: Is code ever finished?

JO: That’s a really good question. Probably not. Someone could come along and improve what you think is finished. Every problem can be solved in a multitude of different ways. What constitutes being finished for one program might be elegance of expression. For another one it might be its performance. There are different value systems for programmers. Code in an open context, that is published openly, tends to be living or have the opportunity to live and be contributed to.

TB: You mentioned that most people do not know what software is, would you mind elaborating on that?

JO: Software in its simplest form is a group of instructions that work together somewhat contiguously to process data with an intended outcome. Data itself is everything that is not program code and program code itself is instructions written in a human readable language that are compiled into a form that the computer can understand. Computers have their own language; they are interpreters in a sense. You can really understand software as an automation of multitudinous processes to speed up the production of an intended or desirable outcome. Decision-making can occur, so it is not just a one-dimensional procedure. For the user though, software is generally just a skin of metaphors. If you think about it, clicking a picture becomes an initiation of an event and software is made to allow for the clicking of pictures to allow it to start a program. I mean software is many things at the same time, a field of illusions and metaphors.

TB: To what extent can you be taken by surprise by the software as an artistic medium given that it is your instructions?

JO: Well it depends on the scale of the project. Much of the time the software is a field of limitations. Working with software is about finding ways to make these limitations work and move within them. Unless you (of course) do something in Processing and you just want it to make a square then you just want the program to do exactly this. But for more complex projects I’d describe computer programming as a process of self-humiliation. It is about finding out how poor your initial assumptions about your own abilities are, you feel frustration and you need to fight against your own attention deficit disorder. It is a conversation with yourself, self-development ultimately. Secondly, it is a process of breaking down big problems into smaller ones until so much of the smaller problems are solved that the big one is solved too. But first and foremost I think that software development is self-development.

TB: Speaking of self-development. It is interesting to note that you have in a way returned to architecture, the difference being that you are not sculpting the physical space but the immaterial space. Maybe more so than building things one could say that you deconstruct them, take them apart through intervening and disrupting space.

JO: Yeah. Danja and I work together a lot these days and we refer to ourselves less as artists than as critical engineers. We firmly believe that the most transformative language of our time, one that defines whole economies, I mean how we trade, how and what we eat, how we converse with each other, how we move around the world is engineering. Art itself is increasingly diluted in transformative power, it has become more like entertainment than necessarily anything that is intrinsically rigorous. In the early days of the 1920s and 1930s we had interventionists’ strategies that are now known as art but they didn’t call themselves artists at the time. So as I have been saying to myself quite a lot recently it doesn’t matter if I call what I do art, others will do it for me anyway. So I better describe myself as a critical engineer by taking the language of engineering and lifting it out from a strictly utilitarian space and look at it as a language for rich, critical inquiry and really take on that challenge. It is really about taking the language of engineering and blowing it wide open, taking it away from this kind of black box reality, of big companies making stuff for civilians. This is essentially our relationship to technology. The companies and government make technologies upon which we depend and I think as any technology becomes more ubiquitous like smart phones our ignorance increases. With ubiquity comes ignorance and it seems to be a plottable, predictable curve. The idea of being a critical engineer is to intervene at this point and say “No! Stop!”. We need to reflect on what we are working with and how what we depend upon is shaping us. So learning this hard stuff in order to evade the top down superstructure is necessary.

TB: This might be a good transition to talking about Newstweek, a project that precisely seeks to evade the top down superstructure that you mentioned. How did this project that you’ve collaborated on with Danja Vasiliev come about?

JO: We were at the Chaos Computer Club early this year and we put a little plug into the wall where we put a small router inside. Our goal was really simple, to go into the Berlin congress centre with thousands of hackers and put the thing into the wall and see how long it would last without anybody noticing. We expected it would last a few hours but it was there for the entire conference. One could see it from hundreds of meters away but nobody did something about it, so we realized we were onto something. So we wanted to build a device that looks so much like part of the infrastructure that it would appear harmless.

Newstweek: fixing the facts from newstweek on Vimeo.

The second thing was to couple it with a man-in-the-middle attack and to interrogate what we increasingly refer to as a browser-defined reality. Meaning that if it manifests in the browser, it is somehow authentic. It is this idea of going to a major news site, and as long as what one sees comes from this imaginary thing called a server and propagates in your browser, it is somehow trustworthy. We wanted to explore the limits of the impossibility of intervening in an otherwise top-down distribution of news. We wanted to find an on-the-ground way for civilians to intervene with this authority by manipulating the facts. It is really about allowing for a lateral interception of news sources, such as the BBC, the Guardian and CNN.

TB: Did you also record or document people’s reactions to their suddenly altered or tweaked news?

JO: Yeah, we have done this. The thing for us though was merely to provide a platform. People didn’t really believe that Newstweek worked. So we released the how-to saying here is where you buy the hardware, how you open it up, the firmware, the script, and so forth. Only then we had this quiet retrospect where people were going “aha”. What we have changed is their relationship with their environment. It doesn’t matter whether there has been a Newstweek-device in the environment or not. The very fact that they are looking around them and thinking that what is happening in their browser may have been tweaked is the most desirable outcome. This is exactly what happened. Most of the comments are of that nature, saying, “I will never trust the news again”. I mean, even when the attention for the project falls back to the sleepy town of acceptance, I think we can still be very proud of ourselves.

TB: Not just Newstweek, but much of your work is about intervening in public space and exploring the meaning of place. What do these concepts mean to you?

JO: Well I am very interested in the writings of Edward S Casey and the phenomenologist’s Husserl, Mearleau-Ponty and Heidegger of course. One of the great things that has come out of that thought is that Space in itself does not really exist, just as there is no number 2 in the universe. What we have done is to create a concept in order to pre-empt space, to reduce contingency, and in this way so much scientific thought is about reduction of contingency. Space of course is a projection of mathematical constituents to make determinations. Through mathematics and cartography and the like we have seen a growth in trust in the space model rather than the place model. So what I am really interest in, is that rationalization of place has allowed us to live in cities, which have been atomically and economically particularized, privatized. I am interested in how the distinctions between public and private is often extraordinarily blurry. A good example is the fact that a company can pay to put a huge picture outside your apartment during construction for instance yet when it is a millimetre or two away from your wall it no longer belongs to you. Or when you are drilling a hole through your wall in your house at a certain point you are going to hit the neighbours next door. Where does it begin and where does it end? It really shows that territory and place are just constructions. The same goes for wireless technology.

TB: Why is it important to question the ways in which we experience public space?

JO: Well take my work Artvertiser as an example. We have come to accept that our cities are covered in proprietary imagery. So I find it important to question this read-only space much in the line of ad busting and culture jamming. We just did a big streetwise exhibition in Helsinki where artists chose their brands and they made concise commentary simultaneously finding a new way of being in their city.

TB: Place often resides in memory and to a certain extent requires permanence. With Artvertiser it is only a temporary intervention. In the end the proprietary imagery stays. What do you hope people take away from an artwork like the Artvertiser?

JO: True. But again, the most productive outcome is conversation. We have the public coming up and looking again and again, through the binoculars at the modified billboards. We even had security guards getting angry. I mean all we are doing is producing a new experience in the visual cortex. Why would a member of the public like the security guard get angry that we are modifying our own experience voluntarily? It is kind of curious.

A Computer in the Art Room: The Origins of British Computer Arts 1950-1980

Catherine Mason

ISBN: 1899163891

JJG Publishing 2008

Computing anywhere else but its history often seems like a carefully guarded secret. This has been alleviated by activity around the resurrected Computer Arts Society in the 2000s, notably the acquisition of CAS’s archives by the V&A and the CaCHE project at Birbeck College which ran from 2002-2005. CaCHE, run by Paul Brown, Charlie Gere, Nick Lambert and Catherine Mason, produced conferences, exhibitions, and publications including the book “A Computer In the Art Room”, by Mason.

The art room of the title is the art department of British educational institutions prior to art becoming a degree-level subject. From the 1950s to the 1970s, when the cost of computing machinery dropped from the level where only major government and corporate organizations could afford them to the level where you only needed a second mortgage to afford one, the best way for artists to get access to the enabling technology of computing machinery was usually in an educational institution.

Mason starts out by describing the artistic and art educational situation in the UK at the time of the Festival Of Britain and the foundation of the ICA in London in the early 1950s. She then explains the structure and significance of the emergence of Basic Design teaching, the impact of the Coldstream report on art education, and the rise of the polytechnic colleges over the next thirty years. This provides vital context for the emergence of art computing teaching in the UK. It is also of more general interest for British art history. Conceptualism, performance, Land Art, the Hornsey Art School occupation, and the educational and media graphics that are currently being used as the basis of “hauntological” art all share this background and can better be understood and critiqued with better knowledge of it.

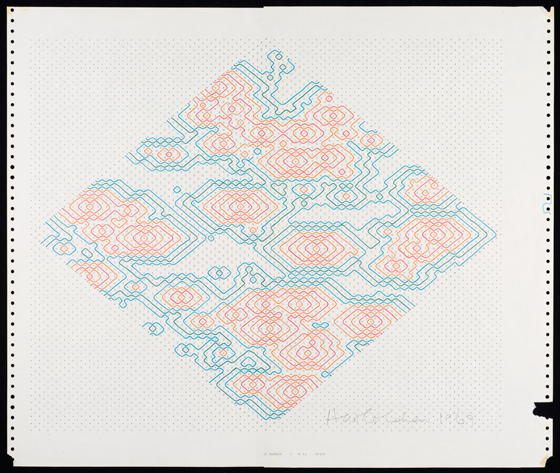

Basic Design courses started in London but didn’t remain there for long. They spread and matured throughout the UK, becoming entangled with the earliest teaching of art computing in provincial technical colleges. Mason traces the family trees of art computing teaching over time through these institutions and back to London-based institutions. Some of the names are familiar from art history (Richard Hamilton, Stephen Willats), some from art computing history (Harold Cohen, John Latham). Where the people involved cross over with cybernetic art, Conceptualism or other artistic currents Mason shows how their ideas fed into and from their art computing work.

The conceptual content of art computing followed the Bauhaus, cybernetics, systems, sociological and environmental influences on art from the 1950s to the 1970s. Its technological forms likewise followed those of mainstream computing. In the 1960s time was leased on mainframes or computers were built by hand. In the 1970s, minicomputers became available and art domain-specific software frameworks or programming languages were written by their users. In the 1980s, workstations with touch tablets, framebuffers, and increasingly proprietary software brought previously unprecedented power and ease of use at the cost of more fixed forms.

The history that I had to piece together as a student from hearsay and from hints in old publications, of the PICASO graphics language at Middlesex University that I found a print-out of the manual for when I was there in the 1990s, of Art & Language’s use of mainframe computers, of early cross-overs between art computing and dance, of cybernetic systems and games that attracted mass audiences before disappearing, is detailed, illustrated and contextualized in page after page of descriptions of hardware, software, institutions, courses and projects. The detail would be overwhelming where it not for Mason’s ability to bring the human and broader cultural aspect of it all to life.

There’s Jasia Reichardt’s Cybernetic Serendipity show at the ICA, Andy Inakhowitz’s Senster robot, John Latham’s dance notation experiments, The Environment Game, and computer graphics drawn with the languages and environments developed in UK art institutions. There’s pictures of the computer systems at the Slade, the RCA, Wimbledon and other art schools that serve as insights into the artists’ studios. There’s the Computer Arts Society, IRAT, APG. And, crucially, there’s the links between them told in a narrative that is coherent while still presenting the breaks and false starts in the story.

The history of “A Computer In The Art Room” reads all too often as brief moments of individuals triumphing against the odds to produce key works of art computing then fading into obscurity, academia or commerce. But any art history that considers a specific context at such a level of detail will look like this. Mason describes works, institutions and artists that deserve broader recognition, although she is under no illusion about how far the road to that recognition may be, citing the example of how long it has taken for photography to be recognized as art in the culturally conservative UK.

The social and pedagogical changes of the period covered by “A Computer In The Art Room” reflect a time of hope and ambition for education in society that made the academy less remote. Mason provides the social, technological and educational context needed to appreciate the very real achievements of art computing that she describes against this backdrop. As a slice of art history this is richly detailed. It touches on subjects far beyond art computing that will help any art student of history better understand the period covered. And it is both a relief and an inspiration to finally have a public record of this important aspect of the history of art computing in the UK.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Space Invaders

Tomohiro Nishikado’s classic videogame Space Invaders from 1978 can be seen as a metaphor for the Cold War and the fears for an approaching nuclear war. An extraterrestrial army are marching rhythmic and increasingly closer to Earth. Only a lone cannon stands between the intergalactic monsters and the total annihilation of mankind. The lonely hero struggling against evil is a theme that we recognise from myths, films and books. Space Invaders with its clear and pedagogical symbolic language has inspired several contemporary artists to describe the eternal struggle between good and evil in our time.

In the British artists Thomson & Craighead version Triggerhapppy the enemy aliens are replaced with quotes taken from the French philosopher Michael Foucault’s essay “What is an author?” “Triggerhappy” is a work that explores the relationship between hyper-text, author and reader. What is a writer, or rather, who is the artist when we are dealing with interactive art in the form of a videogame? Is it Tomohiro Nishikado who created the original game or is it Thomson & Craighead that have modified the game or the player that are playing the game or maybe the computer that creates and interprets the text (the code) that make the game appear on the screen?

After the 11th of September the world suddenly saw a new major enemy, international terrorism. In a modernized version of “Space Invaders”, the artist Douglas Edric Stanely located the scenario in the game to the Twin Towers in New York, which was destroyed during the terrorist attack on 11th September 2001. In Stanley’s version titled the invaders, you have to fight against the hostile aliens before they completely destroy the two towers. The classic struggle between good and evil continues, the game concept is the same as in the original but the scenario and the metaphoric meaning of the aliens has changed.

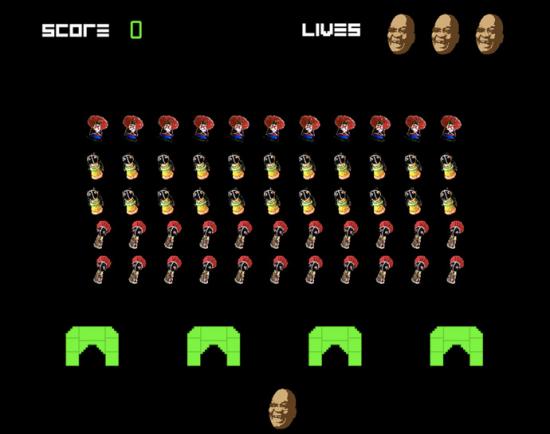

The struggle between good and evil can also be found in other areas of our society, for example in class and gender struggle. In the South African photojournalist Nadine Hutton’s version Skirt-Invaders the main character in the game is Jacob Zuma, South African president since 2009. Zuma has been quite controversial because he is a polygamist and has expressed his doubt about the dangers of AIDS. In the game Zuma you have to shoot down a never-ending stream of virgins from the Zulu tribe. Will the president succeed to shoot down any threatening scandals before they land on the ground? Hutton’s work is an example how a well-known videogame can be used for political purposes and be both entertaining and still very critically at the same time.

The term mash-up, which is frequently used today, could be described as a form of digital collage. Ryan Sneider has created mash-ups by combining images from various sources, in this case photographs from Life magazine’s archives and videogames. The photomontage Duck Hunt / Space Invader shows a bird hunter with a dog, but it is not birds the hunter aims for, instead it is the famous monsters from the “Space Invaders”. Those who played videogames in the 70 – and 80’s will probably remember the game “Duck Hunt”, where you could shoot ducks that flew up out of the reeds and your faithful dog then ran to fetch them. Sneider has combined the two game ideas, one composed of a photo of a true hunter with a dog and the second of digital graphics from the videogame “Space Invaders”. The work discusses the boundaries between the real and digital world. What will happen when these two worlds become more integrated and the borders are increasingly blurred?

Finally we have to mention the artist, who personifies the game, the French street artist who hides behind the pseudonym Space Invader. His main art project consists of invading various cities around the world and putting up small mosaics of characters from videogames as “Space Invader”. For each successful invasion, he collects points, and the whole art project is described on his website as a reality game. Like other forms of street art “Space Invader” is an ongoing battle about the public space. With help of popular culture Space Invader tries to infiltrate the commercial forces that almost have total monopoly on the imagery that appears in our public spaces. The aliens, in form of small mosaics, become a force that can not be defeated when they are spreading all over the world. A important part of the game “Space Invaders” is that you cannot win, you can certainly come to the high score list, but you can never defeat the aliens, they are instead coming in faster and faster each time they are shot down. It’s obviously a dystopian world view we meet in the videogame, but if we look at it from the artist Space Invaders point of view, it’s rather something positive. The art is a force that will not be stopped. The invasion has just begun and the struggle between good and evil continues…

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Pong. Part 1 by Mathias Jansson.

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Tetris. Part 2 by Mathias Jansson.

Form+Code In Design, Art and Architecture

Casey Reas, Chandler McWilliams, LUST

2010, Princeton Architectural Press

ISBN 9781568989372

Form+Code is an art computing programming primer. Rather than teaching any particular programming language it explains the technical and conceptual history of programming and its use in art. Starting with an introduction to the basic concepts of coding, instructions, form, and different ways of representing them (in sections titled “What Is Code?” and “Form And Computers”), it moves on to chapters covering “Repeat”, “Transform”, “Paramaterize”, “Visualize” and “Simulate”.

The basic concepts of programming are explained clearly with plenty of examples of code, hardware, and output. They are also related to broader art history, with examples drawn from conceptual artists such as Yoko Ono and Sol leWitt. And it’s good to see Jasia Reichardt’s pioneering work in bringing art and code together is recognised not just in the form of the Cybernetic Serendipity show at the ICA in London but her books and articles on art computing as well.

There is a little code, enough to give a flavour of what it looks like but not enough to intimidate. Listings in or examples of output from BASIC, LOGO, BEFLIX, Hypertalk and other important historical programming languages are presented. PostScript is given its due, with listings, examples of output and a discussion of its incredible impact on the graphic design industry.

Form+Code is about hardware as well as software. The Difference Engine, ENIAC, oscillioscpes, the PDP-1, arcade games machines that used vector graphics, and the Atari 2600 are all included in a historical narrative of computing and art. The book also describes and shows examples of output from printing hardware from pen plotters through laser printers to CNC and stereo lithography machines, providing a historical and conceptual grounding for thinking about the most advanced output devices currently available.

“Repeat” is explained starting with the Jacquard Loom, and the art of Bridget Riley and Andy Warhol before moving on to variations on a simple BASIC program with illustrations of its output. Packing this amount of historical, computer science and artistic information into each chapter would be overwhelming were it not for the book’s clear writing, structure and design.

“Transform” touches on Holbein’s “Ambassadors” and Victor Vasarely’s Op Art as well as the basic mathematics of folding a piece of paper. “Parameterize” has Dada, Duchamp, the Beats and Calder’s mobiles. It mentions grids without mentioning Rosalind Krauss (the book as a whole is pretty much Theory free), and explains how you use variables to produce variants on the same form.

“Visualise” and “Simulate” are almost devoid of (non-computer) art historical examples and cultural context. Harold Cohen’s AARON is illustrated, and Douglas Hofstadter, Richard Dawkins and Stephen Wolfram’s ideas are mentioned. More people should know about the wokr of Hofstadter’s FARG, and the concepts, work and writing presented are still a treasure trove of information and inspiration. But these chapters lack the art historical context of their predecessors.

The contemporary visual art computing presented is mostly in the generative art / data visualisation mold. It’s highly structured, would mostly be impossible to produce without computers, and is haunted by the possibility of being merely decorative. The only academically recognisable critical art included is one of JODI’s less threatening browser pieces. But the example of worldmapper.org in the chapter on visualisation shows how the aesthetic tools of data visualisation can be used politically. And the formal structures and creative strageties of much of the art has a quality of realism in the age of networks that is a challenge to Theory rather than a falure to illustrate it.

The success of books intended to provide a comprehensive foundation in an area of the study of art, such as “Art In Theory” or “Basic Design”, have both helped to enrich the study of art and had the unintended consequence of closing off other possible narratives. Form+Code stands to be as successful in its own area as those books were in theirs, with the same benefits and dangers. Form+Code’s ommission of virtual reality, livecoding, and other movements within art computing are understandable given its focus, but hopefully won’t lead to their neglect by students.

Could you code up any of the software art that you see in the book after reading it? No. The only code listings are historical fragments. But after reading the book you will undestand the concepts that you need both to figure out what more you need to learn in order to program such art and to understand why doing so is aesthetically and art historically worthwhile. And some source code from the book, in various programming languages, is available online.

Form+Code’s major achievement is that it presents technical, art historical and technical historical information in such a way that it complements each other and builds a bigger picture that demonstrates the wider relevance and further potential of art computing programming. Having read it, you’ll know more and you’ll both want to and be able to learn how to do more. It’s clearly laid out, packed full of illustrations, occasional code fragments, plenty of references to sources for further investigation, and even has a good index. It really is a foundation course in a book, providing a sound basis for further learning or research.

If you teach art computing, and if you are teaching art, graphic design, textiles, fashion or architecture then you are teaching art computing to a greater or lesser degree, then Form+Code is a perfect primer for the conceptual, historical, and cultural side of computing and art computing. Outside of education, if you are involved in art, computing, or are a non-programmer computer-using artist Form+Code provides a good grounding in the concepts used in programming for art computing.

Form+Code serves as a complete introduction to the conventional history, concepts and practice of visual art computing. It presents that information in the context of the broader history of art and design. And it provides enou

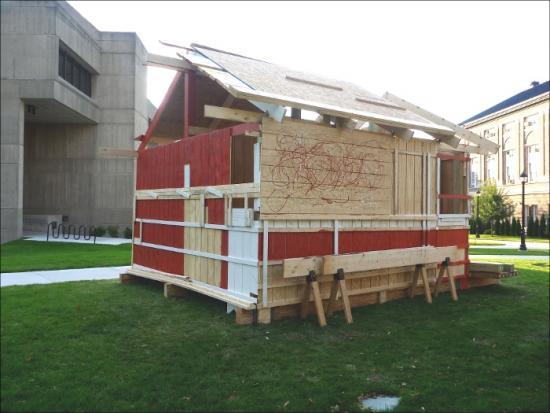

All Raise This Barn – a group-assembled public building and/or sculpture.

“Artists MTAA are conducting an old-fashioned barn-raising using high-tech techniques. The general public group-decides design, architectural, structural and aesthetic choices using a commercially-available barn-making kit as the starting point.” -MTAA

Eric Dymond: Could you give me a brief history of MTAA?

T.Whid: Mike Sarff (M.River of MTAA) and I met in college at the Columbus College of Art & Design in Columbus, OH. We both separately moved to NYC in 1992 and started collaborating as MTAA in 1996 first on paintings and then moving on to public happenings and web/net art. We’ve been collaborating since, showing our work via our websites at mteww.com and mtaa.net. We’ve earned grants and commissions from Creative Capital, Rhizome.org and SFMOMA and shown at the New Museum, 01SJ Biennial, the Whitney Museum and Postmasters Gallery.

ED: The All Raise This Barn project uses one community to design and another to construct. Barn raising is itself a communal activity, drawing out the best in people and providing a place of sustenance for the Barn owner. How did you come to use a Barn Raising as the central performance subject?

M.River: From the start, Tim and I have been interested in how groups and individuals communicate. How do we speak to each other? What rules do we use? How does communication fail or how can it be disrupted? What is the desire that engines (TW: controls?) all of this – and so on. This interest in exchange is what attracted us to the Internet as a site for art in the beginning.

Along with communication as text, speech or image, we like to use group-building as a method for working with non-verbal communication. We’ve built robot costumes, car models, aliens and snowmen with large and small groups. It’s a type of building that is intuitive and open to creative improvisation. This kind of intuitive building is heightened by placing a time constraint on the performance. In the end it’s not about the end object, which we always seem to like, but more about the group activity.

So, at some point we began to think how large can we do this? A barn-raising seemed like the next level. It’s bigger than human scale and contains a history of group-building. Barns also have a history of being social spaces. Your home is your world but the barn is your dance hall.

ED: Did you envision it as a community event from the beginning?

MR: Yes. An online community, a physical community and a community that overlaps the two.

ED: It’s a hybrid work that draws upon some important conceptual precedents. The instructional aspect takes Lewitt and turns the strict instructions he uses upside down by allowing online decisions to drive the design. Did you find the responses to the online polling surprising?

MR: Yes and no. Like the other vote works we have produced, Tim and I set up how the polls are worded and run. So, even though we try to keep the process as open as possible, the nature of how people interact is somewhat fenced in. Even with a fence, people will find a way to move in strange directions or break the fence. It’s not that we think of the surprising answers as the goal of the work, but it is an important part of the process.

ED: There is also the performance aspect which I find exciting. The performance from both events are well documented. Were there any concerns regarding the transfer of the polls instructions to physical space?

MR: We had the good fortune of doing the work in two sections. When Steve Dietz commissioned ARTBarn (West) for the 01SJ Out of the Garage exhibition, we spoke about the sculpture as a working prototype for how a large pile of lumber could be group-assembled in a day with direction from Internet polling. From this prototype we then had a model for how to go about ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC.

Tim and I had a few loose ground rules on how to approach the translation. One was that we would leave some things open to the interpretation of the crew. Another was that both Tim and I had our favorite poll questions that we tended to focus on. It was impossible to do everything as some polls conflicted with other but some details liked ghosts, dripped paint and open walls seemed to call out to us.

Kathleen Forde, who commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC, spoke about these details as where the work became more than the sculpture. The small details held the whole process – material, design polls, and performance together.

ED: I think this comment on the details is right. On first glance there is a fun, open appeal to the work. But when you look at the overall project and how the different phases are tied together it becomes really complicated in the mind of the spectator. There are also different definitions of spectator in this work. The spectator who answers the poll, the spectator on the net who is grazing through the documentation, the ones who engage in the physical construction and those who witness the completed barn. It’s not a simple piece when we perform a detailed overview. Did you think about the various types of spectator that would spin off the project? Were the possible roles for the spectator considered after the fact or were they part of the planned concept?

MR: The “ideal spectator” thought first came up for us in a project called Endnode (aka Printer Tree) in 2002. For this work, we built a large plywood Franken-tree with a set of printers in the branches and a computer in the trunk. We then built a list-serve for the tree as well as subscribed it to a few list-serves. When people communicated with the tree, the text was printed out in the exhibition space. At first we talked about the ideal viewer as one who communicated with it online and then saw that communication in the physical space or vice versa.

Now I feel that the ideal spectator hierarchy is not as important and possibly limiting. Each experience should be whole as well as point to the larger aspects of the work. People can come in and out of the work on different levels. You voted. You followed the performance documentation. Are you missing an experience if you did not build with us or see the results? Yes, an activity is missed. Can you experience that activity thorough documentation. Somewhat. Are you going to have a better understanding of the work. Probably not. Even for me, some aspect of the work will not be experienced. In Troy, they are programing it as a meeting place now that is it is built.. When they are done with it, they will dismantle it and rebuild it elsewhere as a work space.

I say all this even though it is interesting to me that a work can move in and out of levels of viewer experience. I’m not sure as to the draw of it yet but I do not feel it is about an cumulative effect.

TW: Since Endnode I’ve always liked the idea of an art work that exists in multiple (but overlapping) spaces with multiple (but overlapping) audiences. With our pieces Endnode, ARTBarn and Automatic For The People: () there are 3 distinct (but overlapping) audiences: the online audience, the audience in the physical space and the (select few member) audience that experiences the entire thing.

ED: It’s that opening of possibilities that makes this ultimately a networked piece on many different levels. I find the idea of two barns, a few thousand miles apart yet linked by common purpose really intriguing. I’m talking about the whole set of experiences, not just the physical space of the barn. There’s a collapse of Geographic distance for the community and a richer experience because of that. Was the project conceived as two distinct locations or was that a fortunate turn of events?

MR: Fortune. Kathleen Forde, commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC then Steve Dietz commissioned the beta version for the 01SJ “Out of the Garage ” exhibition. Everyone liked the idea of the work arching across time and location. We all also liked the idea that the materials would be reclaimed after it stopped being a sculpture. For me, the reclaimation of the materials to use for a functional structure is the final step of the work.

ED: As the final step, the reclamation removes the common space where the community currently shares the sculpture. Does this mean you are going to use the online documentation as the artifact, coming full circle to where the piece began? Is it important to you that the communal memory will share this role?

TW: Yes, the documentation is the artifact. The barn structure or sculpture itself had been conceived as being physically temporary from the beginning.

ED: Thanks to both of you for your time and for this work.

Introduction:

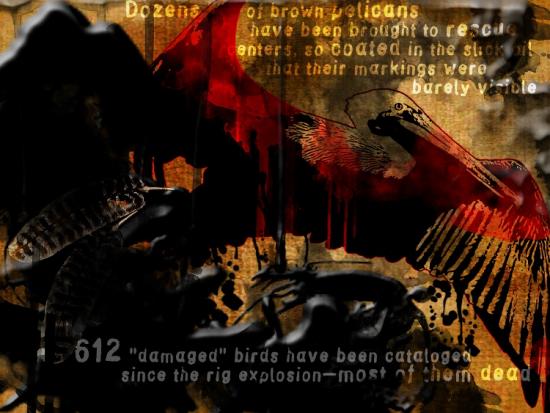

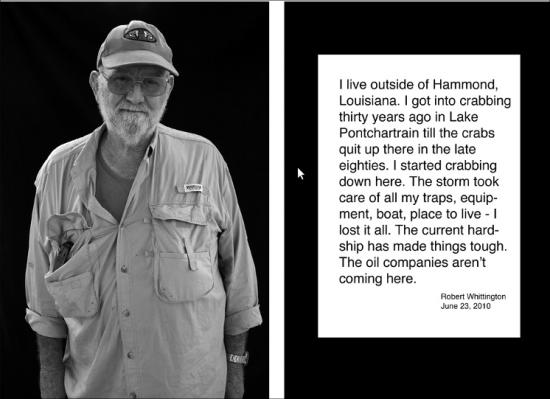

As media attention wanes, the impact of British Petroleum’s Deep Horizon, off-shore drilling disaster continues to unfold. Artists worldwide respond to this new ecological catastrophe in a group show organized by Transnational Temps, an arts collective exploring the interstices of art, ecology and technology. For Andy Deck, one of the founding members of Transnational Temps and the curator of the show, “After a decidedly unsuccessful round of climate negotiations in Copenhagen, the disaster in the Gulf of Mexico frames this exhibition of Earth Art for the 21st Century.”

Now hidden from view by BP’s media campaigns and other de facto censoring actions, the images of oil-covered birds struggling to breathe and fly, oil and dispersant-coated fish, dolphins and whales washing up dead while most sink to the ocean floor, have all but vanished. Partially filling the void are the artists showing here who are recreating topographies: mapping the course of a deadly shadow over our shores and waters; and reinterpreting the sea, its rising levels and largesse, before the vicissitudes of man and nature. Transnational Temps.

———-

Spill >> Forward by Transnational Temps describes itself as an Online Exhibition. It is a website containing images and other media on the theme of oil spills. Some of the images were shown at the MediaNoche gallery from July 30th – November 19th, 2010, with works added or removed so it isn’t just an online catalogue of a meatspace show.

The front page of the site warns that you’ll need a browser that supports HTML5 video and audio, and states that you can view it using patent-free media codecs. From a Free Software and Free Culture point of view this is excellent, your ability to view the art is not restricted by anyone else’s technological or legal machinations. This is also good from an artistic point of view. The software used to view the art can be run and maintained by anyone, making it more accessible, exhibitable and archivable. But this freedom doesn’t extend into the work itself. some of the art uses proprietary software, and none is under a free Creative Commons licence.

The image on the front page, or possibly the image exhibited at the entrance to the exhibition, is not advanced HTML5 video or canvas tag animation but an animated GIF. A Muybridge-ish series of still images of a pelican in flight flickers rapidly up and down as it descends behind an iridescent oil slick that solarizes the bottom half of the image. It’s an effective image in itself, a visually and net.art-historically literate statement that also serves to set the stage for the rest of the show.

This is clearly a politically motivated exhibition, with the theme of the exhibited art centred on a specific historical event (the Deepwater Horizon disaster). Oil spill and petrol station imagery dominates . The resulting art varies from cooly ironic asethetics (Ubermorgen), photo and video journalism (Guillermo Hermosilla Cruzat, S.Slavick & Andrew E.Johnson, Chris Dascher, Adrian Madrid), agitprop (Eric Benson, Geoffrey Michael Krawczyk, Alyce Santoro, Russ Ritell, Terri Garland, Patrick Mathieu), photography(Jessica Eik, Sabina Anton Cardenal), painting(Jessie Mann), collage(Ume Remembers), performance art(Graham Bell), interactive multimedia (Gavin Baily, Tom Corby, Jonathan Mackenzie, Chris Basmajian, Matusa Barros, Mark Cooley), augmented reality (Mark Skwarek and Joseph Hocking) and drawing (Cristine Osuna Migueles, Adrienne Klein, Jesus Andres, Sereal Designers) to video and audio art (Irad Lee, Luke Munn, Gene Gort, Tim Geers, Gratuitous Art Films, Alex George, Collette Broeders, Fred Adam and Veronica Perales, Virginia Gonzalez, Henry Gwiazda, Maria-Gracia Donoso, Jeremy Newman).

This is a lot to take in but the diversity of the work is a strength rather than a weakness, building a broad and visceral response to the Deepwater disaster. Verbal responses to the disaster from politicians seem unconvincingly nationalistic and corporate in comparison. It might seem hypocritical for artists to criticise the source of the energy that feeds us and allows us to make new media art. But we are trapped in that system, and we must be free to criticise it.

Politically inspired artworks have a difficult history, tending to be either bad politics or bad art. The art in Spill >> Forward is excellent, though. Some has a more direct message than others. Again the diversity of the exhibition plays a positive role here. The immediacy of the agitprop images doesn’t need art historical baggage to be effective, but that immediacy provides a social context for the more contemplative or abstract works. The more contemplative or abstract works don’t hammer home a simple political message but they provide an aesthetic context for the more direct images. They work very well together.

Some of the pieces in the show are clearly illustrations or recordings of work, some are electronic media that can be played on a computer, some are clearly designed to be experienced specifically through a computer system. If you removed the political theme of the show it would still be a visually (and audially) and conceptually rich cross-section of contemporary art. I was going to write “digital art” there but the show includes painting, drawing, performance, and other analogue or offline media recorded digitally for presentation online. The celestial jukebox is hungry.

If I had to pick out just a few pieces from the show I’d say that I was struck by the sounds of Luke Munn’s Deepwater Suite, by the visuals of Ubermorgen’s DEEPHORIZON, by the monochrome images and text of Terri Garland’s photography, by the video mash-up of Colette Broeders’ Breathe and by the critical camp of Graham Bell’s Radical Ecology. I think my favourite is Mark Skwarek and Joseph Hocking’s “The Leak in Your Home Town”, an iPhone app that uses the BP logo as an Augmented Reality marker to super-impose a 3D animation of the Deepwater leak over live video of your local BP petrol station. It is art that could only be made now, technologically, aesthetically and socially.

The aesthetic and conceptual competence of the artistic responses to the environmental and human crises of the oil spills in Spill >> Forward make the case for art still being a relevant and capable answer to society’s need to make sense of unfolding events. Art can still provide a much-needed space for reflection, and Spill >> Forward creates just such a space in a very contemporary way.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Ambient Information Systems

English, some texts in German. Translator: Nicholas Grindell

400 pages, 6-colour hardbound, 17.5 x 23 cm

edition of 1,500 unique & numbered.

now available at ambient.publishing.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9556245-0-6

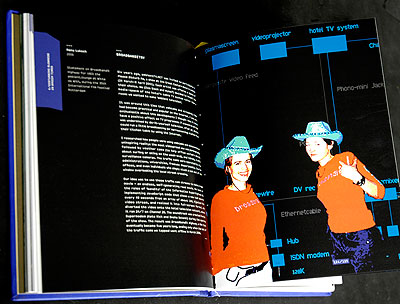

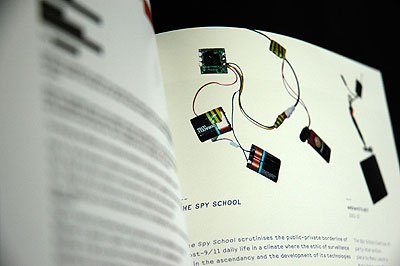

Ambient Information Systems by Manu Luksch and Mukul Patel is a hardback book that presents writing, images and art by and about ambient.tv (Luksch and her collaborators) from during the last decade. Its purple and yellow cover tempered by a tracing paper slip-cover, contains almost four hundred pages of sans-serif text cleanly laid out among images and sidebars. As intermedia artists with a strong emphasis on research and dissemination. Recent works have addressed surveillance, corporate data harvesting, and the regulation of public space.

The material presented in the book ranges from written essays and project proposals through preparatory sketches, computer server log files and video screen grabs to modification of the printed book iteslf by unique rubber stamps and scribbling over sections of text. This diverse and detailed presentation of ambient.tv’s work provides an insight into the inspiration, planning and production of some conceptually and aesthetically rich new media art.

There’s a report from Kuwait during Ramadan 2002, a description of using cutting-edge wearable PCs, a discussion of the role of television, information about the harp in mythology, cyborg markets, the UK Data Protection Act, climate change, anti-gentrification, art and systems theory, UAVs, the Pacific plastic dead zone, and much, much more. There are projects that create free networks, dangerous musical instruments, taped-out surveillance camera boundaries, video installations, photographic images, movies of CCTV footage gained through freedom of information requests, manifestos, snowglobes, and cocktails.

(It’s a fascinating pleasure to read but it’s overwhelming to try and review.)

The portrait of Ambient.tv that emerges from all this is of intensive cultural critique pursued through a playful low-fi digital aesthetic. This isn’t a contradiction, the latter is in the service of the former. Ambient.tv’s projects and proposals tackle serious social and political issues. They do so through skilled use of the aesthetics and attitude of low-fi new media art and technological activism.

The wealth of ideas contained in the essays and other writing in the book show how historical, political and philosophical knowledge grounds the resulting art and indicates how it embodies a critique of contemporary culture.

Contemporary culture as seen by Ambient.tv is surveillance culture, the database state with its DNA databases and laws that protect freedom by removing freedom. Ambient.tv is a realistic project, depicting the hidden forms of contemporary society that intrude into our lives. This is heavy stuff, and to air it critically without alienating the audience it requires precisely the playful touch that ambient.tv often bring to their art.

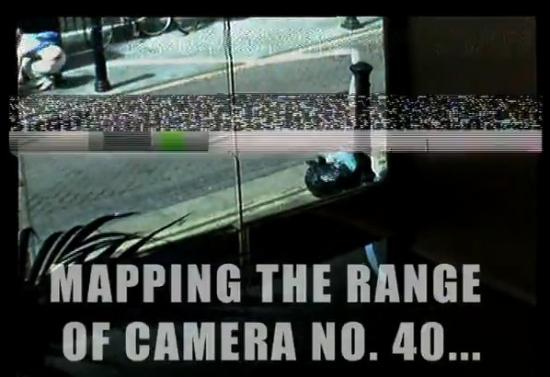

To take the example of FACELESS, 2007, (the first project I personally saw Luksch present), there is an exquisite balance between the disturbing idea of pervasive surveillance, the practical limitations of Freedom Of Information requests, and the visual and science-fictional narrative aesthetic that emerged from this. On their web site it states that it was produced “…under the rules of the Manifesto for CCTV Filmmakers. The manifesto states, amongst other things, that additional cameras are not permitted at filming locations, as the omnipresent existing video surveillance (CCTV) is already in operation.” The result is something more interesting and disturbing to watch than a simple collage of CCTV footage would be. The fact that the work can be made like this, that it can look like this, means something.

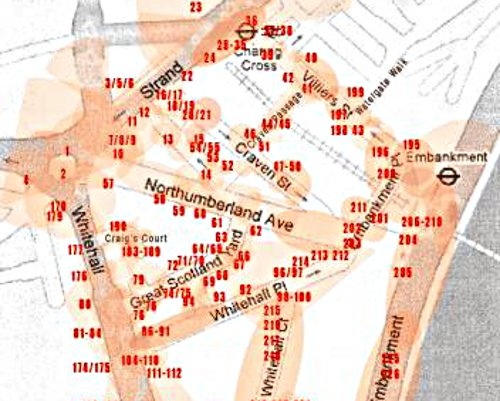

This strategy can be seen in “Mapping CCTV around Whitehall”, 2008, as well, which I also reviewed for Furtherfield here, and in many other pieces by Ambient TV.

Reading the proposals and essays shows the depth I suspected to this work, when I first saw it projected in a darkened room is there in its conception and execution.

It’s an intense and inspiring experience to be faced with the textual equivalent of a decade-long open studio. The first essay in the book, a theory-laden piece by Fahim Amir, is almost overwhelming in a different way. It’s pure Theory, which will hopefully sell Ambient.tv to the artworld sectors that thrive on that sort of thing, but it isn’t the best introduction for newcomers to the project’s very accessible art.

But what a rare pleasure to be given such a wealth of insight into art that so acutely depicts our times. “Ambient Information Systems” is an important resource for contemporary artists and critics, an insight into the ideas and development of a very successful new media art practice. The grungey, playful, important realism of Ambient.tv’s work deserves presentation in a context that shows just what has gone into the art and just what people can get out of it. This is it.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

.re_potemkin is a crowdsourced re-make of the film “Battleship Potemkin”. It is a “.f.reeP_” project by .-_-., part of a series of projects that embrace the ideology and means of production of contemporary media and technoculture in order to make art.

From December 2006 to January 2007 .-_-. worked with 15 groups of students from Yildiz Technical University to reproduce Battleship Potemkin on a shot-by-shot basis. Not all shots were reproduced, there are empty black sections in the new film. The students and the setting of the university and its surrounds are very different from the locations and actors of Battleship Potemkin. The domesticity, institutional backdrops and modern street furniture would be very different from the 1920s Soviet backdrops of the original even if they weren’t in colour.

Soviet film-maker Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin” (1925) is a classic of early 20th century cinema, a piece of obvious propaganda that both fulfils and transcends its instrumental purpose with its exceptional aesthetics. Its most famous images have become cultural icons and cliches. If you haven’t seen it then ironically enough it’s on YouTube so you can watch it there and go “oh, that’s where that came from…” before we continue. Or you can watch it in the side-by-side comparison with .re_potmkin on the project’s homepage.

The Soviet dream became (or always was) a nightmare, an ideology that sacrificed many millions of lives in order to maintain its fictions. Our contemporary liberal democratic society regards itself as unquestionably morally superior to communism for this and many other reasons. The (self-)defining difference between Soviet communism and liberal free-market capitalism is economic ideology. Free markets benefit individuals by reducing inefficiencies.

As free market capitalism has triumphed its means of production have evolved. Corporations emerged as a leading way of organizing labour, leading to utopian social projects in the West in the same era as Eisenstein was working in the East and later to a burgeoning middle class in the post-war era. But since then corporations have become increasingly unapologetic exploitative economic projects.

In order to cut costs and become more economically efficient, corporations can become virtual. They shed jobs to reduce payroll and other costs associated with actually employing people. They then source cheaper labour and production from outside, paying other companies to make the branded goods that the corporation sells. This is known as outsourcing.

A logical next step in corporate cost reduction is to source labour from individuals without paying for it at all. This is known as crowdsourcing. Although individuals who donate their labour to a corporation through crowdsourcing might not be compensated monetarily, they can still be compensated in other ways.

With crowdsourced intangible goods the best way of rewarding people who donate their labour to produce those goods is simply to give the resulting product to them under a licence that allows them to use it freely. Non-profit projects such as GNU and Wikipedia do this very successfully, but corporations are always tempted to try and privilege their “ownership” of other people’s work. Where crowdsourced labour is exploited without fair compensation this called sharecropping.

.re_potemkin is a non-profit project rather than a corporation, and as such it has adopted a GNU or Wikipedia-style copyleft licence. Or at least it claims to have. In a creative solution to the fact that there is more than one copyleft licence suitable for cultural works, .re_potemkin’s licence is a kind of meta-copyleft. Checking the licence page reveals that .re_potemkin’s licence is more a licence offer than a licence.

This avoids the politics of imposing a choice between competing copyleft licences on the producers and consumers of the work. The only problem with this approach is that adaptations of the project, works that build upon it, may end up unable to be combined and built on further because they have been placed under incompatible licences. This is unlikely to happen, but it can be very frustrating when it does.

.re_potemkin is crowdsourced equitably, then. And even in its technical form, .re_potemkin is a free and open resource. it is distributed not in a patent-encumbered, proprietary format such as Flash or MP4 but in the Free Software Ogg Vorbis format. Too few artistic projects follow the logic of their principles in this way, instead sacrificing principle to the at best temporary convenience of the proprietary YouTube or QuickTime distribution channels.

The politics of the production of an artwork are only of aesthetic (rather than art historical) interest if they intrude into the finished artwork. A crowdsourced artwork such as the Sheep Exchange is about crowdsourcing as well as being made by it. The aesthetic of that work (many differently styled drawings of sheep) raises the question of how and why it was produced and this feeds back into the aesthetic experience.

.re_potemkin does not follow the classic crowdsourcing model of an open call for volunteer labour on the internet. It was produced by many groups, but in a closed community. It functions more as an allegory of crowdsourcing than as a literal example of it, but this adds to the project artistically, creating a layer of depiction. The means of production are aestheticized in a way that presents them for the viewer’s consideration in way that can be understood and contemplated more easily than an amorphous internet project.

The “commons based peer production” of free software and free culture is not, to use Jaron Lanier’s phrase, “Digital Maoism”. But the comparison is a useful one even if it is not correct. Utopianism was exploited by the Soviets as it is exploited by the vectorialist media barons of Web 2.0 . re_potemkin gives us side-by-side examples of communism and crowdsourcing to consider this comparison for ourselves.

Within the work the similarities and differences between the original film and its recreation vary from the comical to the poignant. Students in a play park acting out shots of soldiers on a warship, hands placing spoons on a table cloth, crowds gathering around notice boards. This isn’t a parody, it’s an interrogation of meaning. And it is a strong example of why political, critical and artistic freedom is at stake in the ability of individuals and groups other than the chosen few of the old mass media to organize in order to refer to and reproduce (or recreate) existing media.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Article by Rosa Menkman

Based on an interview with the Critical Glitch Artware Category organizers and contenders of Blockparty and Notacon 2010: jonCates, James Connolly, Eric Oja Pellegrino, Jon.Satrom, Nick Briz, Jake Elliott, Mark Beasley, Tamas kemenczy and Melissa Barron.

From April 15-18th, the Critical Glitch Artware Category (CGAC) celebrated its fourth edition within the Blockparty demoparty and this time also as part of the art and technology conference Notacon.

The program of the CGAC consisted of a screening curated by Nick Briz, performances by Jon Satrom, James Connolly & Eric Pellegrino, and DJ sets by the BAD NEW FUTURE CREW. There were also a couple of artist presentations and the official presentation of a selection of the (115!) winners within the Blockparty official prize ceremony.

The fact that CGAC was coupled with a demoscene event is somewhat extraordinary. It is true that both the demoscene and CGAC or ‘glitchscene(s)’ focus on pushing boundaries of hardware and software, but that said, I (as an occasional contender within both scenes) could not think about two more parallel, yet conflicting worlds. The demoscene could be described as a ‘polymere’ culture (solid, low entropic and unmixable), whereas CGAC is more like an highly entropic gas-culture, moving fast and chaotically changing from form to form. When the two come together, it is like a cultural representation of a chemical emulsion; due to their different configuration-entropy, they just won’t (easily) mix.

But all substances are affected (oxidized) by the hands of time; there is always (a minimal) consequence at the margin. And this was not the first time these two cultures were exposed to each other either; Criticalartware had been present at Blockparty since 2007. Moreover, a culture can of course not be as strictly delineated as a chemical compound; it was thus clear that this year the two were reacting to each other.

While over the last couple of years the demoscene has been described in books, articles and thesis’, this particular kind of ‘fringe provocation’ is not what these researchers seem to focus on; they (exceptions apart) concentrate on the exclusivity of the scene and its basic or specific characteristics. The ‘assembly’ of these two cultures during Blockparty could therefore not only serve as a very special testing moment, but also widen and (re)contextualize the scope of the normally independent researches of these cultures. So what happened when the compounds of the chemicals were ‘mixed’ and what new insights do we get from this challenging alliance (if there is such a thing)?

The demoscene is often described as a bounded, delimitated and relatively conservative culture. Its artifacts are dispersed within well-defined, rarely challenged categories (for the contenders, there is the ‘wild card’ category). Moreover, the scene is a meritocracy – while the contenders (that refer to themselves with handles or pseudonyms) within the scene have roles and work in groups, the elite is ‘chosen’ by its aptitude.

The demoscene also serves a very specific aesthetics, as enumerated by Antti Silvast and Markku Reunanen this week on Rhizome (synced music and visuals, scrolling texts, 3d objects reflections, shiny materials, effects that move towards the viewer – tunnels and zooming – overlays of images and text, photo realistic drawing and adoption of popular culture are the norm). In the same article Silvast and Reunanen declare that: ‘Interestingly, even though we’re talking about technologically proficient young people, the demosceners are not among the first adopters of new platforms, as illustrated by numerous heated diskmag and online discussions. At first there is usually strong opposition against new platforms. One of the most popular arguments is that better computers make it too easy for anybody to create audiovisually impressive productions. Despite the first reactions, the demoscene eventually follows the mainstream of computing and adopts its ways after a transitional period of years.'[1]

More about this can be read at Rhizome’s week long coverage of the demoscene. Silvast and Reunanen’s statement might be most interesting when we move along to see what happened during the meeting of the two scenes.

Co-founded by jonCates, Blithe Riley, Jon Satrom, Ben Syverson and Christian Ryan in 2002, Criticalartware is a radically inclusive group that started as a media art history research and development lab. Since 2002 the group has shifted and transitioned. Criticalartware’s formation was deeply influenced by the Radical Software platform (publications and projects). Since then it has been an open platform for critical thinking about the use of technology in various cultures. Criticalartware applies media art histories to current technologies via Dirty New Media or digitalPunk approaches. Through tactics of interleaving and hyper threading it permeates into cultural categories of Software Studies, Glitch Art, Noise and New Media Art.

During the first phase of Criticalartware (from 2002 – 2007), the group was a collaborative of artist-programmers/hackers. It also functioned as a media art histories research and development lab. In this form, Criticalartware had become an internationally recognized and reviewed project and platform.

When this phase ended in 2007, jonCates, Tamas Kemenczy and Jake Elliott were the remaining active members of Criticalartware. During this time, Elliott and Kemenczy wanted to take the project in a new direction; into the demoscene. This direction has ultimately defined the second phase of Criticalartware; an artware demo crew, making work for and appearing annually at the Blockparty event and Notacon conference in Cleveland.

2010 marked the next important transition for the Criticalartware crew, when it started using the phrase ‘Critical Glitch Artware’- Category. Criticalartware now not only organizes itself around the demoscene but also around the concept of the glitch. While a glitch (not to be confused with glitch art) appears as an accident or the result of misencoding between different actors, CA’s Glitch-art category exploits this possibility in an metaphorical way. Criticalartware is now foregrounding these glitch art works (with an emphasis on the procedural/software works) that have been on a ‘pivotal axis’ of the crew for a long time.

CGA, just like the demoscene, can be described as an open (plat)form for artistic activity/culture/way of life/counter culture/multimedia hacker culture and (unfortunately a bit of ) a gendered community. CA are about pointing out ideas or concepts within popular culture and incorporating (standardizing) these as machines or programs in a reflexive and critical self-aware manner.

CA can also be described as an investigating of standard structures and systems. They are often amongst early adopters of technology, in which they (politically) challenge and subvert categories, genres, interfaces and expectations. But the CGA – artists do not feel stuck in a particular technology, which makes it aesthetically, at least at first sight hard to pinpoint a common denominator.

There is not a real organization within this scene. The artists and theorists are scattered over the world, connected in fluid/loosely tied networks dispersed over many different platforms (Flickr, Vimeo, Yahoo groups, Youtube, NING, Blogger and Delicious).

Because of its bounded, intricate conservative qualities, the demoscene has been an easy target for outsiders to play ‘popular’ ironic pranks on, to misunderstand or misrepresent. A growing interest for the demoscene by outsiders has compelled jonCates and the Criticalartware crew to articulate their position towards the demoscene more extensively. In an interview with me, jonCates articulates Criticalartware’s points and contrasts these with problematic representations of the demoscene within two works by the BEIGE Collective (that in 2002 existed along side the Criticalartware crew in Chicago).

When the BEIGE collective went to the HOPE (Hackers on Planet Earth) Conference in 2002 they made a project called: TEMP IS #173083.844NUTS ON YOUR NECK or Hacker Fashion: A Photo Essay by Paul B.Davis + Cory Arcangel.

jonCates writes to me that ‘this problematic project characterizes or epitomizes a kind of artists as interlopers positionality that i + Criticalartware as a crew has always attempted to complicate. we do not want or understand ourselves as seeking out an ironic or sarcastically oppositional position in relation to the contexts that we choose to work in. we have not set out to ridicule the demoscene or otherwise make ridiculous our relations to the demoscene. in contrast, we set out to operate within a specific demoscene through multi-valiant forms of criticality, playfullness, enthusiasm, respect, interest, admiration, etc… this has also been in efforts to connect this specific demoscene to our experimental Noise & New Media Art scenes or what you Rosa referred to earlier as glitchscene…’

Another point of contention for jonCates is the Low Level All-Stars project by BEIGE (in this case, Cory Arcangel) + Radical Software Group (Alexander R. Galloway). this work is described as ‘Video Graffiti from the Commodore 64 Computer’ (2003) by Electronic Arts Intermix who sells/distributes this work as a video in the context of Video Art.

Low Level All-Stars has been shown at Deitch Projects in NYC in 2005 and circulated in the contemporary art world. jonCates writes to me saying the work seeks ‘to isolate + thereby establish cultural values for this ‘quasi-anthropological’ view of demos as found object + functioning as a tasteful ‘testament to a lost subculture.’ It is now being offered online as an educational purchase for $35 dollars.

However, as jonCates and Criticalartware work in the demoscene demonstrates, the demoscene subculture is not lost, nor over. jonCates moves on by writing that ‘the demoscene is a vibrant whirld wit a dynamic set of pasts + presents. this is another of which many (art) whirlds are possible. we seek to make those whirlds known to each others + ourselves out of respect, curiosity, investment, inclusiveness, criticality, playfullness, etc…’

The Criticalartware crew has been taking part in Blockparty since 2007, when it won the last place in a demo competition and was disqualified. One year later, in 2008, through a number of efforts (including Jake Elliott’s presentation Dirty New Media: Art, Activism and Computer Counter Cultures at HOPE, the Hackers on Planet Earth conference in NYC in 2008). CA was able to mobilize and manifest the concept of the Artware category at Blockparty, a category which Blockparty itself retroactively recognized CA for winning.

In the same year (2009) CA organized a talk at Blockparty in which they revealed the “secret source codes” of the tool they used to develop the winning artware of the year before.

By 2010 CA wanted to expand the concept of Artware within the demoscene, which lead to the development of the ‘Critical Glitch Artware Category’ event. Within the CGAC Compo there where 115 subcategory winners, which showed some kind of glitch-critique towards systematic categorization of Artware. Jason Scott (the organizer of Blockparty) personally invited CGAC to pick 3 winners and present their wares at the official Blockparty prize ceremony. Besides these three winners, CGACs efforts got extra credits when Jon Satrom’s Velocanim_RBW also won the Wild card category compo.

Therefore, not only did CA intentionally open up the Blockparty event to outsiders of the demoscene, it also provided a place for new media art and the glitchscene within the demoscene and got Blockparty to accept and invite the CA within their program. Thus, the outsiders (CA) moved towards the inside of the event, while the insiders got introduced to what happens outside of the demoscene (event), which led to conversations and insights into for instance bug collecting, curating and coding.

The Critical Glitch Artware Category has been accepted by, at least, the fringe of Blockparty 2010. Even though the category itself is not (yet) visible on the website, Satrom’s winning work Velocanim_RBW is. Moreover, CGAC was part of the official prize ceremony, streamed live on Ustream, the live Blockparty internet television stream. So how does CGAC redefine or reorganize the fringe between them and the demoscene and how does the demoscene redefine and reorganize the structure of CGAC?

For now, I think crystallized research into the aesthetics of the demoscene can also help describe the aesthetics within CGAC. Custom elements like rasters, grids, blocks, points, vectors, discoloration, fragmentation (or linearity), complexity and interlacing are all visually aesthetic results of formal file structures. However, the aesthetics of CGA do not limit themselves, nor should they be demarcated by just these formal characteristics of the exploited media technology.

Reading more about the demoscene aesthetics, I ran into a text written by Viznut, a theorist within the demoscene (who also wrote about ‘thinking outside of the box within the demoscene’). He separates two aesthetic practices within the scene: optimalism (an ‘oldschool’ attitude) which aims at pushing the boundaries in order to fit in ‘as much beauty as possible’ in as little code necessary, and reductivism (or ‘newschool’ attitude), which “idealizes the low complexity itself as a source of beauty.'[2]

He writes that “The reductivist approach does not lead to a similar pushing of boundaries as optimalism, and in many cases, strict boundaries aren’t even introduced. Regardless, a kind of pushing is possible — by exploring ever-simpler structures and their expressive power — but most reductivists don’t seem to be interested in this aspect”.

A slightly similar construction could be used for aesthetics within Glitch Art. Within the realm of glitch art we can separate works that (similar to optimalism) aim at pushing boundaries (not in terms of minimal quantity of code, but as a subversive, political way, or what I call Critical Media Aesthetics; aesthetics that criticize and bring the medium in a critical state) and minimalism (glitch works that just focus on the -low- complexity itself – that use supervisual aesthetics as a source of beauty). The latter approach seems to end in designed imperfections and the (popularized) use of glitch as a commodity or filter.[3]

Of course these two oppositions exist in reality on a more sliding scale. Debatebly and over simplified I would like to propose this scale as the Jodi – Mille Plateaux (old version) – Beflix – Alva Noto – Glitch Mob – Kanye West/Americas Next Top Model Credits continuum; A continuum that moves from procedural/conceptual glitch art following a critical media aesthetics to the aesthetics of designed or filter based imperfections.

This kind of continuum forces us to ask questions about the relationships between various formalisms, conceptual process-based approaches, dematerializations and materialist approaches, Software Studies, Glitch Studies and Criticalartware, that could also be of interest or help to future research into the demoscene. When I ask jonCates what other questions CGAC brings to the surface, he answers: