Ami Clarke, The Underlying at arebyte Gallery, London. 20 September – 16 November 2019.

When I enter the arebyte Gallery, I am immediately confronted with Ami Clarke’s Lag Lag Lag, a multi-screen installation displaying the structural model of BPA (Bisphenol A). This compound is a synthetic oestrogen which is a byproduct in plastic manufacturing processes. Its molecules have been recently found in water supplies around the world and are linked to hormonal imbalance. We are consuming molecules of plastic and are bodies are becoming such. BPA is beautifully modelled, a sculptural work in its own right, which is peacefully rotating on the screen. Underneath it, there is a looped script. I managed to grasp a sentence “Capitalism as a state of contingency becomes modus operandi.”

When Lag Lag Lag’s screen switches, it shows fluctuations in stock pice of the top 100 polluting companies in the world, the same big stakeholders who are responsible for over 70% of Earth’s pollutions. These statistics are accompanied by sentiment analysis of Tweets, also showing different datasets which are being analysed; emotional, joy, disgust, fear, sadness. Most often used in marketing for specific audience targeting, it indicates how our minute online actions can also be used to influence the already violent financial market.

Clarke’s virtual reality work, Derivative, could as well be a digital trip to London in the aftermath of capitalism. Right after entering the experience, one can hear birds singing into the void and the wind carrying sand throughout the city maze. Its particles make up conical slopes in the corners between translucent buildings, which break up the surroundings into diamond-shaped fragments. I overcome them, slide a few inches above the ground by moving my thumb forward on the VR controller, which is increasingly making me lightheaded. The environment is blanketed with orange, eerie fog, reminiscent of the scenery from Blade Runner.

Further, the monotony of the landscape is interrupted by glimmering writing above the water surface. I set it as my destination, and move forward to it. The city is larger than it seems and it takes me a while to get close enough to read it. Still, I encounter no other living thing, only the lasers scanning through the buildings and my body, as if looking for sings of life. Eventually, I get to the end of the city, where I read the neon-green gothic script:

Welcome to the Offshore City

the city within the city

the tax haven

within the heart of Britain

Now I know what this place is and I dive further into the Offshore City, the tax haven for foreign investors, the headquarters for international companies, the slowly-beating heart of the world economy, supported by an invisible pump of the market. This time I am following a massive, burning sun and I encounter places modelled on London’s recognisable landmarks, such as Number 1 Poultry in Cheapside, an infamous suicide spot for depressed bankers, and, at the same time, one of the City’s oldest addresses, named “The Heart of the City”.

By using the lens of finance, Clarke points to both micro- and macro-scale of the environmental disaster and provides an unusual exploration of it. The accompanying rationalisation and monetisation feeds off the situation, and the capitalist system is shown as merciless and capable of using any opportunity to monetise on the dying planet. The lifeless scenery of Derivative directs attention to the inability of capitalist, finance-driven system to deal with its own creation in the light of planetary future.

Only halfway through my time at arebyte, I realise that there are more pairs of eyes in the space than I thought. In three places in the exhibition space, there are installations made of prosthetic eyeballs, glued to the wall, their pupils fixated on various areas in the space. On the one hand, their synthetic, static gaze is reminiscent of the the all-seeing eyes of the CCTV cameras, on the other, they suggest disembodiment as in the sentiment analysis, whereby feelings are mechanically extracted and translated into data. Are we becoming cyborgs, or have we become them already?

The exhibition is a complex puzzle. It tackles difficult subjects, speculating in language, social media and economy. It is a powerful and slightly depressing, but intriguing picture. This dystopian vision of the future prompts questions; is it possible to re-imagine it? Can we come up with new narratives and stories and use speculation as a tool for revisioning the future? Where am I, as a viewer, positioned in the power relations imposed by the corporations and what freedoms do I have? At the time when the issues relating to the climate crisis are debated more than ever before, Ami Clarke’s The Underlying enters the conversation to problematise it through the exploration of technology, proposing a multilayered analysis of human and non-human agencies in the environmental catastrophe.

The above dystopian playlist was made in response to the exhibition. Recommended: listen while reading the review or on your way to the show.

The Underlying. Ami Clarke. Runs until Sat 16 Nov 2019.

https://www.arebyte.com/the-underlying

As part of transmediale’s opening night in Berlin, audiences were sat in front of three large screens and taken on a journey through the abstract infrastructures of the imminent ‘smart city’. Liam Young, a self-proclaimed speculative architect, narrated the voyage whilst beside him, Aneek Thapar designed live sonic soundscapes complementing the performance. For Young, the smart city is a space where contemporary anxieties are not only unearthed but increasingly multiplied. The smart city manufactures users out of citizens, crafting an expanse whereby the hegemonic grip of super-production evolves into a threateningly subversive entity. According to Young, speculative architecture is one of the methods of combating the city’s supremacy – moulding the networks within a smart city to facilitate our human needs within a physical realm. It is a means of becoming active agents in amending the future.

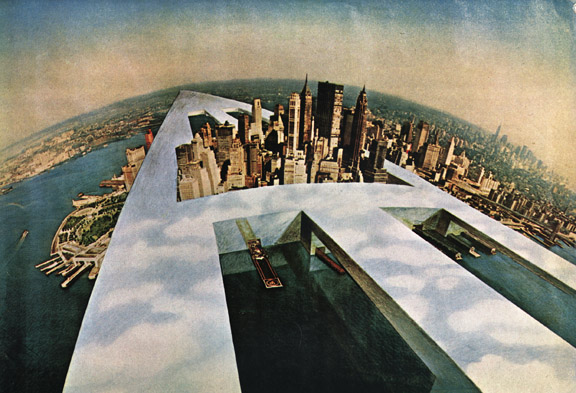

Speculative architecture as a term is relatively new, however the concept’s origins date back to the 1970s Italian leftist avant-garde. Back then it was called ‘Radical Architecture’, a term initiated by SUPERSTUDIO’s conceptual speculation regarding the structures of architecture. SUPERSTUDIO’s methods were transcendental as they favoured the superiority of mental construction over the estranged act of building. The founders of the group, Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, acknowledged modernist architecture as reductive to man’s ability of living a free life since its core foundations were built on putative methods of indoctrinating society into a pointless culture of consumption. The development of The Continuous Monument was a declaration to end all monuments since the structure itself was designed to cover the expanse of the world. Its function was to form ‘a single continuous environment of the world that would remain unchanged by technology, culture and other forms of imperialism’ as stated by SUPERSTUDIO itself. A function sufficiently egalitarian, and in some respects utopic, The Continuous Monument, much like Tatlin’s Third International in the 1920s, was never intended to be built, but instead to uncover the notion of total possibility and arbitrariness. Likewise, Young’s performative smart city does not purpose itself around applicable techniques of construction – it creates scenarios of possibility exploring the autonomous infrastructures that lie between the premeditated present and the predicted future. Hello City! intends to transpire the idea that computation, networks and the anomalies that surround them are no longer a finite set of instructions, but instead constitute an original approach to exploring and facilitating speculative thought through imagined urban fictions.

Liam Young’s real-time cinematic narration cruises us like a ‘driverless vessel’ through the smart city beyond the physical spectrum. The smart city becomes an omnipresent regulator of our existence, as it feeds on the data we wilfully relinquish. Our digital footprint re-routes the city, traversing us into what Young calls ‘human machines of the algorithm’. His narrative positions human beings as ‘machines of post-human production’ within what he names a ‘DELTA City’. As an envisioned dystopia which creates perversions between the past, present and future, Hello City! is reminiscent of Kurt Vonnegut’s post-modern narrative in Cat’s Cradle. San Lorenzo, the setting for Vonnegut’s book, is on the brink of an apocalypse – the people’s only conjectural saviour would be their deluded but devoted faith to ‘Bokononism’, a superficial religion created to make life bearable for the island’s ill-fated inhabitants. Moreover, the substance ‘Ice-9’, a technological advancement, is exploited far from its original purpose of military use, leading to looming disaster. Both Bokononism and the existence of Ice-9 resonate Young’s narrative as they explore the submissive loss of free will and the consequences of allowing the future to be dictated by uncontainable entities. In Hello City! the metropolis becomes despotic and even more complex as it is designed by algorithms feeding on information instead of the endurances and sensitivities of the human body.

Like software constructed by networks, the future landscape will be a convoluted labyrinth for physical beings. Motion within the city will be ordained by a form of digital dérive structured by self-regulated and sovereign systems. Young’s video navigates us through blueprint structures simulating the connections within networks thus proclaiming the voyage as unbridled by our own corporal bodies. The body is no longer dominant. He introduces us to Lena, the world’s first facial recognition image, originally a cover from a 1972 Playboy magazine. Furthermore, he makes references to Internet sensation Hatsune Miku as a ‘digital ghost in the smart city’ whilst the three screens project and repeat the phrase ‘to keep everybody smiling’ ten times. We may speculate that for Young, the smart city has the potential to function like Alpha 60, a sentient computer system in Godard’s film Alphaville, controlling emotions, desires and actions of the inhabitants in the ‘Outlands’. As Young dictates ‘the City, looks down on the Earth’ – it becomes a geological tool and engages the speculative architect to remain relevant within the ever-changing landscape of that space.

In a preceding interview, Young refers to the speculative architect as a ‘curator’, ‘editor’ and ‘urban strategist’ attempting to decentralise power structures from conventional and conformist architectural thought. In 2014, Young’s think tank ‘Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today’ envisaged and undertook a project titled New City. New City is a series of photorealistic animated shorts featuring the cities of tomorrow; one is The City in the Sea, another is Keeping Up Appearances and the last is Edgelands. Too often, these works are projected and interpreted with the foreseeable frowning of rising consumerism concurrent with the dissolute development of technological super structures. Without a doubt, the supposition that technology is alienating us from our identities as citizens of a city is undeniable and exhaustively linked to the creation of super consumers and social media. Nonetheless, New Cities is more than just about that – comparable to the architectural intrusions of SUPERSTUDIO, the narrative of Cat’s Cradle and Alphaville,New City underlines the impending subsequent loss of human liberty with the advent emergence of the smart city whilst Hello City! injects the audience in within it.

Young’s notion of the smart city is consolidated within a Post-Anthropocene existence. Without any dispute, our world will inevitably divulge a post-anthropocene reality, but until that critical moment arrives, acts of speculation, such as speculative architecture, only exist within the hypothesis of potentiality. In fact, throughout Hello City! speculation cannot be positioned as either a positive or negative entity – it appears to lie within a neutral area of hybridity and experimentation. The narrative of Hello City! is purely speculative and thus exceedingly experimental. Like much of SUPERSTUDIO’s existence, antithetical notions of egalitarianism and cynicism run throughout Hello City! triggering perpetual seclusion of the audience’s contemplations. Conflicting positions reveal an ambivalence resulting to escalated concerns towards the act of execution. Speculative architecture itself is a purely narrative process designed on a fictitious future that is not formulated and so the eternal battle between theory and practice will always occur. Uncertainties raise an issue of pragmatism and whether speculation, evidently in architecture, is commendable. Seeing as speculation for the future is, in its most basic form, an act of research, it is regarded as the most pragmatic practise when taking into consideration any future endeavours. As the performance draws to an end, Young declares that ‘In the future everything will be smart, connected and made all better’ and then indicates towards the contradicting existence of Detroit subcultures that the future map will be unable to locate. A message loaded with properties that are paradoxical and thus ambiguous in their intent, Hello City! occupies itself with inner contradictions that only create the possibility for plural futures, a functional commons for the infrastructure of tomorrow.

Roger Malina is a physicist and astronomer, Executive Editor of Leonardo Publications (The M.I.T. Press), and Distinguished Chair of Arts and Technology at the University of Texas at Dallas. Dr. Malina helped found IMéRA (Institut méditerranéen de recherches avancées), a Marseille-based institution nurturing collaboration between the arts and sciences.

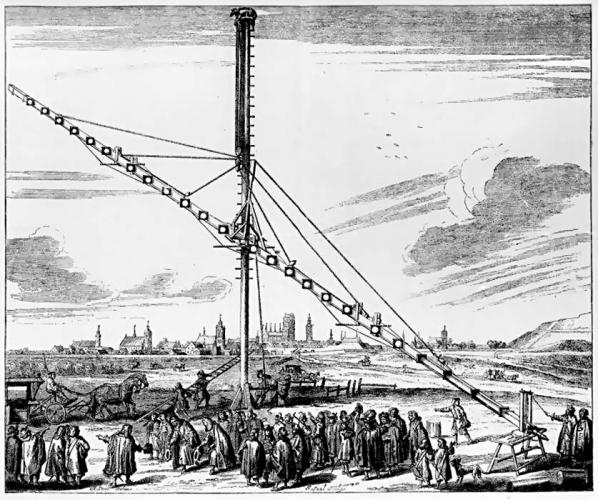

Mariateresa Sartori and Bryan Connell are two artists recently based at IMéRA. Their work connects with human movement through the city, and addresses the intersection between technology and perception. Recent work by Venice-based Mariateresa Sartori has encompassed drawing and video. Bryan Connell, Exhibit/Project Developer at San Francisco’s Exploratorium, works especially with landscape observation devices and mapping.

Lawrence Bird interviewed Roger Malina, Mariateresa Sartori, and Bryan Connell about the intersection of their work with the city. Images above courtesy: Roger Malina, Rita Gambardella, Bryan Connell.

Lawrence Bird: Roger Malina, in your recent writing you make the case that science is no longer just a field of positive knowledge. Scientists are increasingly open to engagement with the arts — for example artists’ residencies at CERN. You’ve even argued that we’re in a crisis of representation as profound as that of the Renaissance or the 19th century, and this is “driving a new theatricalisation of science.”

Urban life has often been understood as performative – display, performance of social roles, presentation of oneself before others are all part of the public life in cities. How would you say that crisis of representation plays out with regards to this performative dimension of urban life? How is science implicated alongside art in the city, in these conditions?

Roger Malina: One of my arguments for the ‘crisis of representation’ really looks at Renaissance systems of representation — first driven by what the eye could see, and then the eye extended by microscopes and telescopes. These systems of representation were developed that led to a deep contextualising of the viewer in the world.

Today we are in a new situation because so much of our perception of the world comes not through extended senses but, in a real way, through new senses. This has been happening over a number of decades; the first wave of this was at the end of the 19th century when there was a cultural shock with the introduction of x-ray images, infra-red and later radio — which didn’t extend existing senses but augmented them.The most recent series of triggers maybe comes from the nano-sciences and synthetic biology — we now perceive phenomena of which we have no daily experience of (eg quantum phenomena). Field emission microsopy or MRI or some of the other new forms of imaging really don’t build on our existing experience — there are discontinuities and dislocations. Another element is of course the hand held device that leads to techniques for ‘augmented reality’ — I have a phone app that I can point at an aeroplane overhead and it tells me what the plane is, where it came from, and where it is going.

Coming to your question about the city — there is clearly a shift in map construction and reading — from the Cartesian map that we have been acculturated to. The ability to toggle between the bird’s eye view and the “street view”, and the ability to view maps that have multiple layers simultaneously are driving artists and others to develop new forms of representation.

Someone whose work is interesting in this regard is Bryan Connell in San Francisco, he just finished an art science residency at IMéRA in Marseille. He was working on a large urban trail project called GR13 — 300 miles through industrial, urban, sub urban, and wild landscapes (the city had a hell of a time getting right of way through these areas). Bryan is currently working on a web site for the Marseille European City of Culture events, where he’s working on some of these questions of representation. The project involves a collective of ‘artist-walkers’ that I think fits right into this question of performativity.

LB: There’s currently a great deal of interest in the connections between representation, digital technology, and politics, for example the current Hybrid City II conference in Athens. As you’ve pointed out, these often underline the connections between what digital media mean for artists and what they can contribute to citizens — what’s emancipatory about them. What can art offer civil life in this context? Are there any conflicts or contradictions in that relationship?

RM: One pertinent example is the work of Bruno Giorgini, a physicist, and Mariateresa Sartori (visual artist) who work on the “physics of the city.” They were recently in residence in the IMéRA Mediterranean Institute of Advanced Study which hosts artists and scientists in residence who want to work with each other. We now have access to incredible amounts of data on human mobility (pedestrian and various forms of transportation) so it is now possible to study human behaviour quantitatively. Sartori discovered that she could tell many things about a person just through the morphology or topology of their movements through the city. Girogini discovered that people’s movements could be predicted at the 80% level, but 20% of the time he had to introduce what he called ‘social temperature’; in discussions he also referred to this as a ‘free will’ parameter. Barabasi has found similar results analysing cell phone GPS data of individuals. So its interesting to think of the development of cities as 80% predictable and 20% serendipitous. This of course then highlights the role of the arts and culture in making cities part of the cultural imaginary that drives people to make choices. Recently Max Schich here at the University of Texas has analysed very large data bases looking at where prominent people are born and where they die over the last 500 years. Immediately you can see how suddenly certain cities become cultural ‘attractors,’ say the way Berlin or Hong Kong are now. And of course cities are now trying to ‘design’ this into the development of cities. Here in Dallas there has been a huge investment in the ‘arts district’ and in institutions of higher learning in the belief that healthy cities require such investments. See for instance the US National Endowment for the Arts Program; there are many similar programs in Europe.

This doesn’t yet address your ’emancipation’ question. One of the things that is happening is that we are becoming a data taking culture (see the recent literature on ‘big data”). The cell phone has transformed every citizen (that has one) into a data taker. Of course much of this data is used by companies for marketing objectives. But many citizen groups are now able to take data for their social objectives. Some of this is captured by the ‘citizen science’ movement ( one example is here). There have been good examples of citizen’s taking data (on pollution, on illegal activities etc.) and then being in a position to challenge ‘authorities’ of various kinds whether scientific, political or economic (see for instance the way citizen groups have mobilised to collect data after man-made disasters such as oil spills, or illegal logging in forests).

A few years ago I wrote an open data manifesto which argued that I would like to advance a new human right and a human obligation:

1. Each of us has the right to the data that has been collected about ourselves and our own environment.

2. Each of must contribute to the knowledge construction by collecting and interpreting data about our own world.

Most scientific data collection is funded by public tax payer funding. The public has a fundamental right to all data collected and funded by public tax money.

LB: How do you imagine an artist’s training will change as these conditions evolve? And a scientist’s — could we foresee any kind of convergence?

RM: One interesting development is a cohort of hybrids, who have one degree in science or engineering and one in art and design ( for example J.F. Lapointe, a researcher at the National Research Council of Canada with degrees in molecular biology and dance) or degrees in Science or engineering and employment in art or design (like myself or Paul Fishwick, a key figure in the field of aesthetic computing). There’s been an emergence of art/science Ph. D. programs that take students from art or design or science or engineering. I suspect this cohort will grow over the coming years.

LB: Mariateresa Sartori, your IMéRA research project with Bruno Giorgini focused on mobility in the city. Can you tell us a little bit about how your work and Dr. Giorgini’s work complemented each other? What kind of evidence did you bring to the table as an artist?

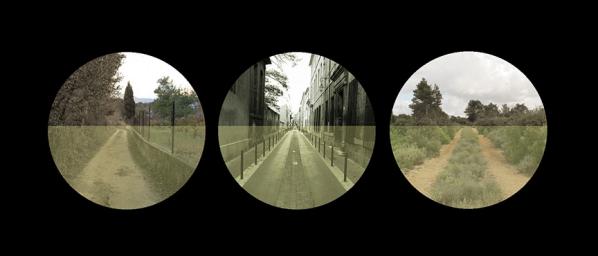

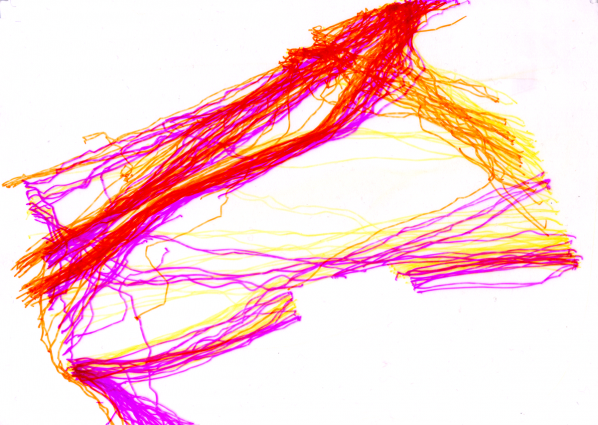

MS: The project I worked on with Bruno Giorgini developed an exploration that began with earlier work in Venice. There I created a series of drawings using a rudimentary, even crude procedure: I traced out the movements of each pedestrian in the Piazza San Marco, drawing their paths with a felt-tipped pen on a transparent sheet placed over the computer monitor. I then faithfully transferred the results onto ordinary large sheets of white paper. The lines thus drawn in different directions created a space, drawing a St. Mark’s Square that is actually not there. As well as the actual physical space, it is also a drawing of our individual and collective manner of relating to space. Each single path determines the route of others, in a continuous and reciprocal game of influences that makes our collective progress.

At IMERA we developed this method for a new environment, a city more ethnically and culturally plural than Venice. Together we set up procedures and tools for collecting data about mobility networks there: nodes, links, chronotopi. These drew on the work of Bruno Giogini’s Laboratorio di Fisica della Città of the University of Bologna. We shot videos focusing on specific behavioural patterns where strategies of shifting, approaching and distancing play a decisive role; and we were also attracted by the places and situations of pedestrian congestion. Using the same technique as in Venice, I translated these into drawings of movement. These again created a space that marks out squares and places which are actually not there, each synthesizing space, time and humanity in a single image.

LB: Is there an emancipatory or governance-related dimension to this work? Degrees of mobility have human rights implications. How does your work as an artist connect with these rights, especially the notion of the right to the city?

MS: The first goal when I work as an artist observing reality is observation, i.e. a way of observing that implies a new attention. The result is always instructive because I do not have particular expectations. After lines have been traced following my process, something always emerges and what emerges can be a useful and indicative element for the emancipatory dimension of the urban condition. I would say that Bruno Giorgini is more involved in that dimension than me, especially in the notion of the right to the city.

LB: There’s a current preoccupation among researchers in a number of fields with the relationship between representation, often engaged with/through technology, and urban life. How has your latest work connected with this relationship?

MS: My way of working with technological instruments such as computers is very particular and limited. I use the computer as a technical tool strongly mediated by the senses, i.e. by human perception. I am very interested in modalities of perception: they are so imperfect, yet sufficiently perfect to make our existence possible.

LB: You described the way you work with technological instruments as “particular and limited.” Another way to look at this is that you make the technological system slow down by inserting yourself into the process… and the result is your drawings, which still movement. Might this be one role for art — to insert the human into the machine? Much net art focuses on flows of information, virtual movement, and representing that. While not quite glitch art, do your representations of movement in some sense intentionally put a brake on the machinery?

MS: I find your words enlightening, you describe my way of working better than me….. Actually I insert myself into the technological process…..but this is not a statement of a position against technology.

I can say that what interests me the most (and art’s relation to science is just one instance of this) is the thread of connection between specific cases and general theory, between subjective and objective. Between, on the one hand, the singularity of events and, on the other, general theory. The individual’s experience is singular, unique; but there is always a thread, even if fine, that leads each individual case to a wider generalisation. What interests me is this incessant – indispensable as much as concealed – mental activity that every day leads us to search for generalisations and regulating principles. What interests me is the human tendency to comprehend phenomena, even the most complex, via schematic representation, via a generalisation that leads to the identification of organising principles. I mean “Comprehension” in very wide sense, where emotions and feelings participate too in embracing reality, including reality. Maybe in this sense I put the human in the machine…

There is a discrepancy between how we perceive reality, mediated by our senses, and the truth decreed by science. On a rational level we recognize the truth, but we cannot internalize in a deep way this knowledge; this is beyond our human capabilities. I think that in my artistic research I find myself in this deep discrepancy.

LB: Bryan Connell, your work in Marseille addresses, among other concerns, technology and its relationship to nature. Do you see the urban environment as playing any particular role in that relationship — of having a particular status in our negotiation of it?

Bryan Connell: One of the things that intrigued me about the metropolitan hiking trail in Marseille is the way it plays with our sense of meaning and value in the exploration of contemporary landscapes. Most long distance hiking trails are designed to lead out of urban environments, not into them. We don’t usually think of carrying a field guide that illustrates the taxonomy of fire hydrants, electrical pylons, or urban weeds on an extended city or suburban walk. That kind of engaged, systematic attention is usually reserved for wild natural terrains. From a traditional environmental perspective, the less altered a place is by human technology, the more scientifically interesting, ecologically exemplary, and aesthetically rich it’s going to be. Without undermining the validity of ever-present environmental concerns, the trail functions as an invitation into a more challenging and complex relationship to the emerging para-wilds and novel ecosystems that are arising at the intersection of the natural world and the technological infrastructure of the built environment.

Similarly, the Marseille trail doesn’t really focus on the kinds of urban sites that are traditionally thought of as having significant historic, architectural, or cultural interest. Instead, the trail route incites visitors into an exploration of the everyday environments and working landscapes of the contemporary urban transect – a world of parking lots, freeway overpasses, suburban developments, abandoned railways, and semi-rural wildlands.

Landscape ecologist Earl Ellis argues that to better navigate our way through the current geohistorical epoch, the Anthropocence, we must expand the traditional ecological concept of regional biomes into the parallel notion of “anthromes” – biomes that are complex interconnected melds of human technology and natural systems. In a sense, the GR 2013 Marseille trail is a sketch or system of exploratory paths into what a publically accessible, anthrome based urban ecology observatory might look like.

LB: A similar question is in relation to the image, especially sequential images. What does it mean for our negotiation of the relationship between nature and technology? Between science and art?

BC: We increasingly live in a networked digital metropolis with an image and information density that both mirrors and exceeds the high population densities of the physical metropolis. One topic of particular interest to me is the role these images play in transfiguring the quality of our desire. To what extent do scientific or aesthetic images that increase our ability to find meaning and satisfaction in observing and understanding urban landscape phenomena mitigate our need to physically alter the landscape to conform to an idealized image of what it should or shouldn’t be?

For example, the Marseille metropolitan trail didn’t require much physical alteration of the terrain – it’s a conceptually designated network of pre-existing roads, paths, streets and highways. The trail’s function is not to alter place, but alter the cognitive landscape of trail users so they have a richer sense of place. If you are fascinated by the diversity of ways a para-wild plant population has adapted to a technologically modified environment, do you need to engage in an energy and material intensive re-landscaping of that environment with a palette of conventional horticultural plantings to make it more “beautiful”? In this sense, constructing interpretive images of landscape is more than a way of augmenting a recreational hiking experience, it’s a way of shifting and re-configuring what we think we have to consume and alter to find meaning and vitality in contemporary landscapes.

http://uranus.media.uoa.gr/hc2/

Hybrid City is an international biennial event dedicated to exploring the emergent character of the city and the potential transformative shift of the urban condition, as a result of ongoing developments in information and communication technologies (ICTs) and of their integration in the urban physical context. After the successful homonymous symposium in 2011, the second edition of Hybrid City has grown into a peer reviewed conference, aiming to promote dialogue and knowledge exchange among experts drawn from academia, as well as artists, designers, researchers, advocates, stakeholders and decision makers, actively involved in addressing questions on the nature of the technologically mediated urban activity and experience.

The Hybrid City 2013 events also include an online exhibition and workshops, relevant to the theme

Hybrid City Conference 2013: Subtle rEvolutions will take place on 23-25 of May 2013.

The Hybrid City II events will take place at the central building of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

This document was edited with the instant web content composer. Use the online HTML editor tools to convert the documents for your website.

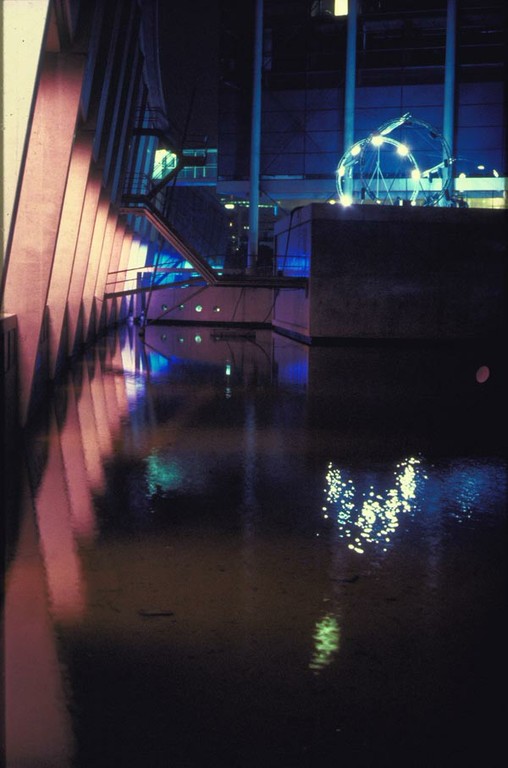

Andreas Broeckmann writes on art, machine aesthetics, and digital culture. He is director of Leuphana Arts Program at the university in Lüneburg, and has played key roles at transmediale – festival for art and digital culture, ISEA2010 RUHR, TESLA-Laboratory for Arts and Media, Berlin, and V2_Organisation Rotterdam, Institute for the Unstable Media. Lawrence Bird interviewed him on our current experience of media and civil society. Image: A. Broeckmann, transmediale 2007 (© Jonathan Gröger)

Lawrence Bird: It’s often said that we inhabit the city differently today because of our engagement with media and media technologies. This has been one of your main concerns, and it makes for a very interesting intersection of media theory and public realm theory. Where does this preoccupation come from on your part?

Andreas Broeckmann: I have arrived at these questions not so much from a theoretical or academic perspective, but in response to specific artistic practices that I was interested in. For my own thinking about this area, the works that the artist group Knowbotic Research were working on in the 1990s were seminal. The participative public installation “Anonymous Muttering” (1996), for instance, initiated a radical clash of the physical urban space with the virtual ‘space’ of the internet, interlacing the activities of the participants in a way that created a strange intermediate zone – maybe we could say that it allowed people to place themselves _in_ the medium. In the series of projects that followed under the title “IO-dencies” (1997-99), Knowbotic Research further explored the possibilities of becoming active, of acting in a virtual environment in a manner that was connected to activities and events in the physical space.

I was working quite closely with the group at the time, presenting some of the projects in Rotterdam where I was a curator at the V2_Organisation, co-authoring texts, organising workshops, etc.. This was a great opportunity to think through the issues of the new, hybrid public sphere that was opening up because of the Internet. In order to understand the works, it was necessary to develop a differentiated conception of what it meant to “be public” or to “become public”. The topic returned, for instance in projects I was involved in by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer in Rotterdam, or a publication on Polish video art by the WRO agency, or a major curatorial on a media facade in Berlin, or, for that matter, more recent projects by Knowbotic Research, like “Be Prepared Tiger”, or “MacGhillie”. Personally, I believe that privacy in all its guises – from camouflage and the absence of surveillance to “a room of one’s own” – is one of the great privileges of a modern individual. Contemporary media and communication technologies have transformed the possibilities of being private dramatically, just as the notion of what it means to be public is subject to drastic changes. And artists are articulating these changes which we are all part of, giving us opportunities to reflect on what is going on, and to imagine how things might also develop otherwise. I think that my interest in the relationship between publicness and intimacy is fed both by a personal sense of urgency and and concern, and by the inspiration I get from artists, not to fall into despair.

Lawrence Bird: Fascinating. So would you say that in the direction media are now evolving, there’s actually an increased scope for private “being” — not just in terms of a potential for increased anonymity and independence, but in terms of a richer and more developed individuality? To a greater degree — or perhaps qualitatively different — than was possible in earlier stages of modernity?

Andreas Broeckmann: Unfortunately not… I say that privacy is a privilege exactly because it is becoming such a rare condition these days. The developments that we speak about are, of course, not unidirectional and homogeneous, but very diffused and heterogeneous, and open to quite different interpretations. For many people, a platform like Facebook or Google-Plus is a way of discovering a new form of sociality in which they try out different ways of being public and being private.As for myself, having been brought up with the Critical Theory analyses of the Frankfurt School, I find it difficult not to see these optimistic readings as dangerously naive – it would be a bit like exploring your inner self in the highly regulated and commercial spaces of a shopping mall… I would not go so far as to say that privacy has completely disappered — as though we were now living in a global village of Big Brother containers, or in a vastly extensive version of the Truman Show. But I do think that today we lack a more widespread critical sense of resistance to the regimes of commodification that have taken the place of what were once “privacy” and “social relations”.

Lawrence Bird: You spoke about the concern of “falling into despair”. How general would you say that motivation is? I don’t know if you’ve thought about it this way, but I’m thinking in terms of Occupy, and the other social movements, many of them enabled by media and engaged by artists, which seem to generate new, and some evidence suggests quite lasting, relationships of trust and hope. Many of these seem to come in response to a recent loss of faith in corporations, governments, financial institutions — older social groups that had an important role in old definitions of “public”. I wonder if your comment connects with a widespread yearning for hope, in response to conditions that might well produce despair?

Andreas Broeckmann: I dare not speculate about the longevity of the relationships that have been built by the different branches of the Occupy movement, but I am skeptical about the longevity of anything that is built on specific internet-based media platforms. Facebook, for instance, was launched in 2004, that’s eight years ago, and the German and many other non-English Facebook services are no older than four years. That’s a very short time, and we might want to remember that platforms like Google (*1998), Facebook, Flickr (*2004) or Twitter (*2006) are not part of the natural environment, but recent services offered by profit-oriented companies which, just as well as they may rule the internet world throughout the 21st century, might also get drowned in the swamps of global capitalism (whose regime includes “customer confidence”).

I would refute the assumption, implicit in your question, that many of the people who protested on the squares in Madrid, Cairo, Washington or Athens last year were people who previously had faith in their governments, or the institutions of capitalism. Of course they didn’t, and quite rightly so. What was special about last year was that there is a new, articulate generation of people who would not put up with the situation of stasis, hopelessness and frustration that has paralysed major parts of global societies since 2003 when, in February of that year, millions who took to the streets around the world in protest, were not able to stop the US government and their allies from starting the war on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. The inflection of this event is different in different parts of the world, but I believe that we share that moment. And this is where the protests in the Arab countries, and those in Spain and Greece, hit the squares on a parallel trajectory: In the same year of 2003, the German government started the implementation of what was called the “Agenda 2010”, a project based on the EU’s 2000 Lisbon agreement of economic restructuring, with the aim of making Europe more competitive on the global market. Since then, in Germany we have seen an erosion of the welfare state, drops in income for lower and middle classes and a huge increase in precarious jobs. But some economists also say that the reason for Germany’s relatively healthy economic situation today, compared with, for instance, Greece or Spain, is that these countries failed to reform their debt-pampered economies. Which is why there is a certain reluctance today in Germany to protect privileges for the Greek middle class, privileges which German citizens already had to give up years ago.

above: Tahrir Square on February 11, by Jonathan Rashad (CC-BY-2.0, 2011).

My point is that if we take things into a more extended historical perspective, and if we count our lives not in short Twitter months, we can see how the struggles, the hopes and the despairs of today are part of a broader set of transformations. And we can see that in these transformations there are forces at work which have a huge inertia and which need to be worked on and battled with both patience and long-term strategies. Like any other revolution, and like in the theatres of the Occupy movement, the one in Egypt may have started on Tahrir Square and the mobilisation of people through media-based social networks, but to complete that revolution, a difficult and drawn-out political struggle needs to be fought. Maybe that is the necessary realisation that hit “the movement” this past winter.

Lawrence Bird: And what form might those long-term strategies take? It’s a huge question perhaps, but do you have any ideas about the shape this restructured public sphere might have to take, what forms of governance and participatory democracy for example, to sustain a more permanent change?

Andreas Broeckmann: Personally, I believe that for the foreseeable future many political struggles will continue to happen in the ‘arenas’ of political institutions like governments, parliaments and other election-based structures, in political parties, public administrations, in transnational and inter-governmental decision-making bodies, in trade unions and NGOs. It is a realm that will only partly be affected or influenced by the online world, and even if the emerging public sphere of the Internet and its social media forums implies a huge expansion and diversification of the mass media dominated public sphere of the 20th century, this expanded public sphere will not necessarily have a bigger impact on political processes than the ‘old’ public sphere did. The experience of the ‘movement’ in Egypt today might be analoguous to that of the APO (the extra-parliamentarian opposition of the students movement) in 1960s and 70s West Germany, i.e. realising the necessity of getting involved in existing state institutions (“the long march through the institutions”), which brought members of that generation to power some 25 years later in universities, in parliaments, in national governments. The relevance and standing of the new Egyptian parties is not proven or disproven in the first elections; it is decided when in ten or twenty years from now they may or may not have been able to change the social consensus about democracy, rights, and freedom.

Lawrence Bird: A confession here: I’m an architect, so I always assume, perhaps naively, that a built infrasructure can play a role in these kinds of transformations. In your opinion, might a material intervention be a necessary part of those changes — distinct from, though perhaps in dialogue with, the mediated public realm? What kind of physical (urban) spaces might serve as a counterpoint or moderator to the transience of the Twitter world — and are those spaces any different from the urban spaces we have now?

Andreas Broeckmann: I doubt whether architecture in the narrower understanding of the term will play much more than a symbolical role in these struggles and transformations. Of course, the built environment, especially the way in which public space is configured, plays a significant role in how public life can unfold in cities. And there are political issues to be fought over: for instance, I find it curious how in many of the European cities the authorities allow the construction of one shopping mall after the other, pushing the social and commercial activity of shopping into privatised and highly regulated control spaces, and then those same authorities are surprised when the neighbourhoods in the vicinity of these malls deteriorate because the normal shops are abandoned or have to be closed, making room for trash and money laundering businesses. The resistance against such developments can at times most effectively be fought in local parliaments that, at least in Germany, have to give their consent to such major construction projects. This makes it necessary to join a political party, get elected into the local parliament, sit around in meetings, deal with all sorts of issues of public interest, etc., and be there when the application for the next shopping mall is up for decision…

Of similar relevance is the designing of the digital sphere through software ‘architectures’ – both in terms of individual applications and services, and in terms of the overall technical infrastructure, both hard- and software, and its governance. The critical discussions around the status of ICANN and, more recently, the public protests against law-making initiatives like SOPA and ACTA, have shown that protests can in fact have an impact on such structures. Yet, that impact will remain cosmetic if the public outcry is not followed up by sustained political work through which the drafting of and the decision-making on such laws is factually influenced. This is what lobby groups do, and this is what social movements also have to do, finding whatever possible and suitable political instrument or institution through which to act.

The major arena of constructing and designing the new political sphere will be in law-making, and I believe that the movement needs critical lawyers, historians of economy and charismatic intellectuals more urgently than architects – although, of course, everybody has an important role to play and no-one who wants to contribute should be sent away.

Lawrence Bird: And how about artists — do they have a role in this? To provoke, perhaps? To articulate social and political conditions? Would you say that whatever that role is, it can be part of the sustained transformation you’re talking about — or do they need to step down into a governance role to take part in that (Vaclav Havel being one example).

Andreas Broeckmann: In my understanding of art, there is no particular role that it can, or even “should” play. I would argue that the most important aspect of art for society is its autonomy and the fact that it has no particular responsibility. Art can beautify, it can decorate, it can irritate, it can disturb, it can question, it can affirm, it can simplify or complicate. Such an “open program” of course implies that individual artists or groups, or specific projects, will take a particular political stand, will try to influence a social or political situation — will seek real impact. This is a form of activism that art can borrow from political groups and movements, but it is not the activism that is crucial for the artistic practice, it is the transgressive articulation that artists may achieve in their own dealing with social realities. I want to emphasize that this is my understanding of art, and I fully respect people who think that art can and must be more engaged in social processes in order to be relevant. But again, I think that what art can give us most importantly is what happens in a zone of freedom that is morally, aesthetically and sometimes also politically more risky than anybody who acts in the political arena — save for the mavericks — would want to be.

So the question, “what should artists do,” can in my understanding only ever be answered: “they should do whatever they do.” It must be the best thing that they can do, they have to be precise in their formulations and realisations, they have to be committed, diligent, and daring. It is wonderful if they can, in that way, help proliferate good ideas and push the political situation in a good direction. But by the same token I believe that it is equally wonderful if artists ask questions that are impossible to answer, or pointing out unsolvable ethical dilemmas, or remove the mask of an opponent only to don it themselves.

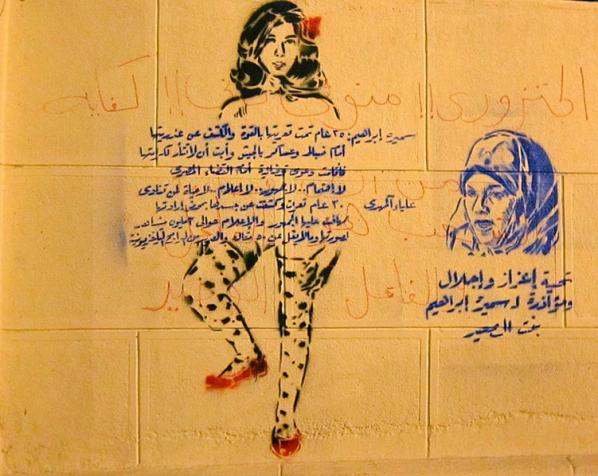

There is, in my eyes, certainly no obligation to go into politics like Havel did. Artists are not always people with a high moral reputation, and stepping into the political arena like Havel did requires stamina and a certain habitus. And there are many ways in which people can intervene in social and political processes. Take the example of Aliaa Magda Elmahdy who posted a photograph of herself naked on her website and sparked a huge debate about the situation of women in the Islamic world. This was not an art project, but it shows what work in the realm of symbols can achieve.

Lawrence Bird: If I could I’d like to steer the conversation in the direction of your thinking on “the wild” — perhaps it relates through the transgressive nature of art you’ve just been discussing, and the tricky relationship of that to civic functions, governance, and related realms of responsibility. Cities have been conceived as set apart from the wilderness — within the city lay the realm of humanity, civility, politics; outside its walls, the wild, monsters, raw life. Girorgio Agamben makes the case that the violence of our times equates to the obliteration of that line: between political life (zoe) and bare life (bios).

In light of what you’ve already said about art and transgression, and the value of that; and the precarious status of privacy today, and the danger of that; your understanding of media and the political movements underway today which involve some significant transgression of the boundaries of authority, I’m willing to bet you have a more nuanced take on this issue. What’s our condition now with regards to the edge of the wild? Is it a constantly shifting boundary, what Agamben refers to as the caesura? Does it imply a human condition interdigitated with an inhuman condition, like a werewolf, or cyborg? Does our humanity in fact find its source in the wild?

Andreas Broeckmann: The questions that you raise are of course extremely complex and very difficult to do justice in the current context. So allow me to shirk the anthropological discussion, which I guess I don’t have a particularly original opinion on anyway. When I spoke about the “wild” as an aspect of digital art a few years ago, it was in a half ironic, and half romantic way: ironic in the sense that art that makes use of digital media is technically conditioned and requires a “tamed” environment to function at all; even what is referred to as ‘glitch aesthetics’ is predicated on general functionality, the glitch being only a minor aberration, not a substantial fault. Yet, as you would gather from what I said before, I am also ‘romantically’ attached to the idea of an artistic practice that transgresses these technical functionalities and explores failure, dysfunctionality, misuse, or uncontrollability as categories of aesthetic experience. I’m thinking of artists like Gustav Metzger, Jean Tinguely, Herwig Weiser, or JODI, who in their works perform, we might claim, the potential wildness of technology. This is mostly a controlled, at times even metaphorical wildness, whereas the true wilderness of technology, if we want to go there, is probably the realm of the accident that Paul Virilio has so poignantly written about. An “art of the accident”, as we entitled a festival in Rotterdam in the late 1990s, is, I believe, only possible in the realm of metaphors.

What I’m currently wondering about is whether in our 21st-century cybernated world a notion of “nature” as something different from culture maybe disappears completely, as we have full Google-ised view and total measurability of what happens on Earth, from millimetre shifts of tectonic plates to carbon dioxide output of cattle. In such a world, there would be no room any more for the “wild”, only for different degrees of pollution on the one hand, and endangerment of species on the other…

In the long run I have trust in the finality of all existence, and the futility of all human efforts. But in the short term, that is, in our lives, I believe that we have to work to make the world a little better, or at least do our best to not make things worse than they are.

Featured image: Martijn de Waal, co-founder of The Mobile City, introduces the conference (image courtesy Virtueel Platform)

On Feb. 17th Amsterdam hosted Social Cities of Tomorrow, a conference on new media and urbanism. Adapting its title from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow, but taking equal inspiration from the work of Archigram, the conference presented a snapshot of the direction cities are moving today: as conventional means of planning and designing are renegotiated through our engagement with new media technologies:

Organized by The Mobile City and Virtueel Platform, the event showcased best-practise examples of the use of media in urban analysis, design, art and activism. These ranged from “Homeless SMS”, a text-messaging system designed to provide information to the 70% of homeless Londoners who own cell phones; “Amsterdam Wastelands”, an on-line mapping of disused sites in Amsterdam and Zaanstad; “Koppelkiek”, a game project in which residents of a troubled area of Utrecht collected “couple snapshots” (in couples of friends, relatives or complete strangers), promoting social interaction through play; and “Urbanflow”, and New York-based project to rethink the contents of urban screens. In all, a dozen such projects were presented at the conference.

http://www.socialcitiesoftomorrow.nl/showcases

Immediately preceding the conference an intensive three-day workshop took place at ARCAM, the Amsterdam Centre for Architecture. This event brought together two dozen interdisciplinary creatives from around the world to tackle urban issues in four current case-studies: Haagse Havens, Den Haag; Zeeburgereiland; Strijp-S Eindhoven; and the Amsterdam Civic Innovator Network (a proposal to open up Amsterdam’s civic resources to distributed control by citizens). Working with local stakeholder organizations, the participants brainstormed how to leverage new media to solve intractable or new problems in these real-world sites.

http://www.socialcitiesoftomorrow.nl/workshop/the-four-cases

Also at ARCAM, a roundtable discussion on the alternative forms of trust emerging out of new media conditions was held, with panelists (below, left to right) Tim Vermeulen, Henry Mentink, Rietveld Landscape, Scott Burnham, Michiel de Lange (image courtesy Aurelie).

Keynote speakers Usman Haque, Natalie Jeremijenko, and Dan Hill concluded the conference with a panel discussion that placed the presentations in the context of distributed technology, contemporary art, social innovation, and architecture (image courtesy Virtueel Platform).