Pencil / Line / Eraser, the current exhibition at Carroll/Fletcher, spanning both the main Eastcastle Street gallery and their nearby Riding House Street project space, is well worth a visit. It’s never less than engaging and there are several pieces that lodge, linger and ferment in the mind long after the bus or train ride home.

They describe the show as “surveying recent works in expanded drawing which use paper and line as a point of departure” and, let me say again, whatever I have to say that is critical you won’t waste your time there. Far from it.

This review will be in two parts – first, & with an innocent(ish) eye, I’ll sing the praises of the work that itself sang to me during my visit and then I’ll vent about the things that irritated me, more a question of contextualisation and commentary than of the work itself, although in today’s text ridden and intention trumpeting artworld it’s sometimes a little difficult to unpick one from the other. Since the artists cannot completely escape responsibility this has consequence for any assessment of some of the work.

In a space of their own, a little into the main gallery, there are three pieces by the Portuguese artist Diogo Pimentão and they are delicious – large pieces of heavyish paper covered with graphite and folded, draped and rolled. Two are delicately attached to the wall so they appear to float there and the third sits up on the floor like a long fierce graphite flue.

The works capture superbly paperishness: its particular foldiness, rolliness and drapiness and its ability to suck up pigment in large quantities (fields rather than lines here) Indeed the graphite covering softens the folds and creases so what we experience is a kind of Platonic report on the qualities of paper. The urge to touch this gorgeousness is almost irresistible.

The works strongly recall Richard Serra (though what I perceive as his machismo is entirely absent) – his early large scale drawings using a single dark medium, ink or oil stick, but also the torque and defiance of gravity that is so much part of the steel pieces. I’ve no idea whether this is a conscious borrowing but to point it out is not to criticise the work in any way because it feels like a commonality of subject matter –the stuffness of stuff – rather than technique, despite deceptive (and magically so) similarities of appearance. (It takes a couple of beats to fully realise that Pimentão’s work is work on paper and not something else.)

Further along to the left in the stairwell is one of a number of films by Wood and Harrison. Some of their work strikes me as a tad glib – smart but somehow too undemanding of thought and which tickles the viewer’s tummy (and amour propre) a bit too readily. And I apply this to their other pieces in this show – the paper which moves (conveyor belt?) beneath hands holding both a pencil and then an electric eraser makes me want to shout “I get it, OK , I get it! I get Rauschenberg, I get updating pieces to the digital era, I get a certain fashionable emptiness…”

The piece in the stairwell, though, is a different kettle of fish. Entitled ‘Fan/Paper/Fan’ it does what it says on the tin. A pair of hands places a piece of paper between two fans blowing towards each other in such a manner that the paper temporarily defies gravity and stands on its edge on its shorter side. Well, not so much stands as staggers like a gleeful drunk, manic ballerina or even someone just desperate for a pee. Then it falls and the hands re-position it, and maybe it’s just me (and even if, I offer it to you as an affective pathway to the work) but here, rather than a closing off or a patness, there is a tremendous opening out – the metaphor of the paper’s embodiment resonates with the human figure who intervenes and helps (or tasks) it. It’s difficult to resist anthropomorphising the fans, too, as windheads in map corners or Tweedles Dum & Dee. I’m going to use the artworld kiss of death term “moving” to sum it up.

The second two artists I want to hymn are to be found in the project space. The first is Sam Messenger who makes large scale abstract drawings on dense paper which is subjected to some sort of weathering process – hence, I assume, the mysterious listing of saltwater in the description of one. The net or skein of white pigment which floats upon a dark and varied but subtly modulated wash is applied according to some sort of Fibonacci based algorithm (as per usual with artists and maths the actual detail is elusive). Much play is made of the ceding of control which goes with this, together with the, therefore somewhat surprising, point that this algorithm doesn’t permit a prediction of the drawing’s final state at any point before this is reached. I get it, though, I think – the set of conditions must be firm enough to follow straightforwardly and to yield visually coherent results but at the same time there must be some choices, forks, within the procedure. What this yields is a complex detail nothing short of exquisite. Particularly lovely is the way that the drawings bulge away from the wall and also just how lost in their surfaces one soon finds oneself. It took me a little while to believe that the white “surface” network was not applied in some mechanical way (especially given the prevalence of mechanical /digital assistance/participation in the work of some other artists in the show) but close and detailed examination reveals uncertainties in marking that could come only from a human hand.

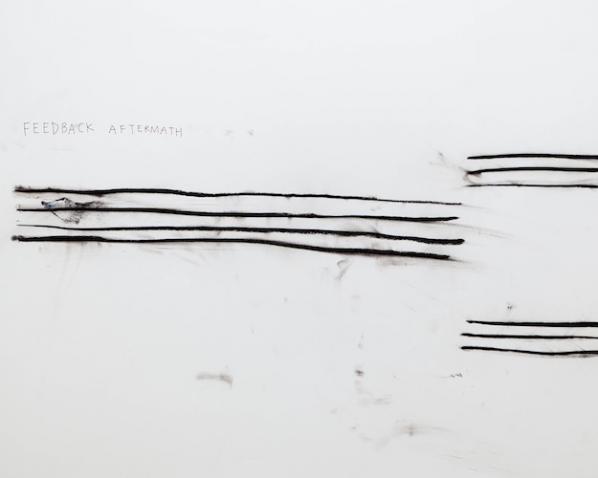

The final piece in this tour of highlights and, on a best till last basis, the one which affected me the most is a single piece by Christine Sun Kim, about whom more after I describe both the work and my first response to it. We see a drawing of a text, of three systems of horizontal lines resembling music manuscript staves (though in each case one or more lines short of the usual five) and smudges. The largest of the smudges and one which suggests it contains some colour – it’s curiously difficult to tell, I think it does – sits athwart the middle system of lines. Elsewhere there are much smaller patches which presumably arise out of a loose way of working with the charcoal of the lines. These lines themselves are gorgeous, varying markedly in width (but remaining lines, not shapes) and performing a similar balancing act with their relation to the horizontal, from which they depart but never enough to threaten our reading of them as such. Above the top left of the system of lines there is a text in clear and deliberate but slightly spidery sober brown capitals which reads FEEDBACK AFTERMATH. “Sounds like the name of a heavy metal band,” I remarked to my companion, who laughed gamely. But there is something bold and mysterious about it. After the band name, motivated in part by the horizontality of staves, their wavering might conjure a seismographic recording, or simply (and especially in the context of this show) some kind of algorithm at work. All this far from exhausts the visual pleasures of the piece. The central positioning of the marks, the feeling of a space divided into mark and void but at the same time a void graduated from nothingness up through a series of increasingly visible smudges. The palpable sense of the performative in a drawing like this. Oh it’s great! I wish you could see it! You can! (until Sept 13th 2014) Go.

On reading the handout we discover that

Christine Sun Kim, who has been deaf since birth, explores the materiality of sound in work that connects sound to drawing, painting, and performance. Her performances are often the starting point for works on paper that display witty evocations of powerful sounds or loaded silences.

I quote it not to flaunt my perceptiveness but to observe how vigorous and alive the work is even without contextualizing info. It wouldn’t matter a two-penny damn if read the “wrong” way either, it’s the sheer power, variety and beauty of the mark-making and its appeal across a whole range of things from cultural codes such as music and language, through graphs and charts through to the facts of our embodiment – our perception of dark and light, our manual dexterity or surrender to chance, the need to play, the right to say ‘fuck it!’ and leave that mark there; to own it.

So what is my beef? Part of it lies in the curatorial notion of “expanded” drawing, a conceptual movable feast. It implies some kind of comprehensible set of practices which make drawing –what? –more expressive, more up to date, capable of things that were previously not possible… I don’t know, neither do you and neither does anyone. At its most straightforward one could read it as works made which are somehow adjacent in some way to drawing –so a number of works involve moving image works of drawings or the act of drawing. But hold on –there’s a perfectly respectable word for this which is animation or, if this is stretching it, moving image work with drawing as its topic. I would be reluctant to call these works themselves drawings, expanded or no, with the exception of Fan/Paper/Fan where a path is drawn by the jittering paper. Likewise much play is made of the uses over the last forty years of mechanical means of ..er..drawing. Except one feels the weight of history and usage would fall more appropriately behind the simple print.

It probably wouldn’t be worth losing any sleep over it all except this comes to a head for me in two large scale works, one at each site. The first is a piece by Raphael Lozano Hemmer whose

Seismoscope device detects vibration around it, from footsteps to tectonic shifts, and records this vibration on paper using an automated XYplotter. As the Seismoscope registers a seismic wave, it is programmed to draw an illustration of a single 11th Century Sceptical philosopher, over and over again. The actual traces of the drawing follow a random path, while staying within the portrait image that has been burned into the memory of the device, thus each drawing emerges unique.

And each of these drawings to date is pinned up on the adjacent wall on a daily basis (although in a move that doesn’t exactly bespeak confidence a “completed” version is retained in the “out” hopper of Lozano Hemmer’s machine so that we can see what it’s like.) What one sees on the wall is a series of drawings which appear to have stopped at various points in the process of being plotted out. It looks as though something about the software tends to create a blotch of ink at that stopping point. Otherwise the images are hard to distinguish. The descriptive text is evasive about how the tremor detection feeds into the plotting process. Does an initial tremor start it or is it merely that the tremors alter the manner of laying on pigment within the template that is already programmed into the installation so the lines go on in different ways within the bounds laid down? The words sledgehammer and nut occur when such a fetishisation of the digital and mechanical is applied to results which are..well… kind of OK-ish but contain, even conceptually (lest I’m accused of being unduly optical) little to move or amaze.

There’s a similar mountain labouring to bring forth mouse situation with Julius von Bismarck & Benjamin Maus’s (ha! Just noticed!) Perpetual Storytelling Apparatus which, in truth, is a beautiful thing to behold –a wall mounted plotter which spews forth a seemingly endless scroll of printed paper, populated, the notes tell us with that hubristic gigantism that so often afflicts such documents, by drawings from “seven million patents – linked by over 22 million references”. The mechanism is easily explained (and perhaps this itself is significant). There is a root text (for one showing it was, apparently, Alice in Wonderland) and by the miracle of software and data equivalence the text is translated into a set of illustrations comprising drawings drawn from the previously mentioned patent database which are then printed out onto the scroll of paper. The artists don’t reveal the source text until after the close of the show. As noted, it’s a handsome process to watch and the drawings have the strange surreal beauty of the technical drawing uprooted from its context but there is an implicit claim made by the artists with their title (supported explicity by the curatorial “New visual connections and narrative layers emerge within the telling of this story through the graphical depiction of technical advancements”) that something resembling a narrative emerges from all this hoo-ha. To put it bluntly – it so does not. You would have to strain your imaginative faculties enormously and do some heavy duty cultural forgetting to even begin to find narrative here, because the images on which the thing piggybacks are so distinctive, strange and beautiful in and of themselves. It’s instructive to compare this rather polished and curator friendly but ultimately disappointing piece with the wonderful and messy anarchy of its distant ancestor, MTAA’s Endnode (aka Printer Tree) of 2002 where a cheap and cheerful plywood tree with printers in its branches dispensed prints of posts to a created-for-the-occasion e mail list. (Images: http://www.endnode.net/install.html background: http://www.endnode.net/index.html)

So I want to finish by saying, once again, this is a great show. There’s a lot of good stuff I haven’t even mentioned, some of Evan Roth’s work in particular. But its basis bothers me a lot – I’m certainly very far from wanting to exclude the digital, the mechanical and the procedural from an as yet to be really seriously defined expanded drawing practice but at the moment it is still drawing’s appeal to and demands on the artist’s embodiment and our embodied imagination that give rise to by far the most engaging work here.

Pencil / Line / Eraser

At Carroll/Fletcher

1 August – 13 September 2014

JENIFA TAUGHT ME

CONSTANT Dullaart’s solo show Stringendo. Vanishing Mediators, Caroll/Fletcher.

Occupying both floors of the ultimate O’Doherty white cube of Carroll/Fletcher, Dullaart’s first solo UK survey show Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators consists of 27 works – many of them newly commissioned. The works have in common Dullaart’s pervasive aspirational tactic of queering and laying bare the architecture – both physical and virtual – of our networked yet doggedly analogue broadcast lives. Retaining a sense of sepia-tinted nostalgia for the Pong era Internet, many of the works in the show pay tongue-in-cheek homage to the revolutionary and democratic aspirations placed on the web at the beginning of its popular adoption – albeit primarily by white, male middle class Americans. Throughout the exhibition, Dullaart forensically tracks, seeds and traces remnants of our digital past and places them in direct dialogue with the power relations embedded in the terms and conditions of how these technologies have remediated the way we encounter and interpret our world now. This unveiling and excavating of the digital gesture – whether personal or brand mediated – and the freezing of the smoke and mirrors affect of software semantics isolated on the plinth of the gallery. It will be familiar ground for many of us in the business of the aestheticization of our precarious position as prosumers in surveillance society. However, as Dullaart lays bare the soft terrorism of the interface and the slowly encroaching disillusion of the clunky binary “digital” and the “physical”, he points towards a new way of visualising the architecture of our messy public/private, social/political pathological states of disarray by introducing The Balcony as a newly envisaged site of resistance and broadcast.

Stepping off the street and into Constant Dullaart’s recent solo show Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators at Carroll/ Fletcher on a sweltering summer afternoon I am immediately transported into a trippy AC’d noughties Snappy Snaps.

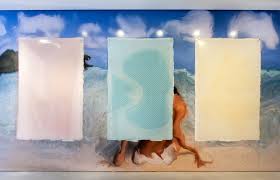

Dullaart’s signature, and now Guardian-famous, eponymous series Jennifer in Paradise acts as the hero image for the immersive world of blissfully glossy software-mediated wallpaper and slickly produced lenticular prints hanging in the entrance gallery. A Miami-hued display of software’s extensive lexicon of brushstrokes, filters and masks is flamboyantly demonstrated on the lonely yet aspirational image of a beautiful woman sitting on the beach looking out onto the tropical horizon. The promiscuous past of this image is well rehearsed; from its origins as a 1987 holiday snap – taken by co-creator of Photoshop John Knoll – to its use as crash test dummy for his ground-breaking popular software and its voracious adoption by the newly indoctrinated Photoshop masses as a subject of visual vivisection frames the staging of this exhibition. Dullaart’s archeological impulse to sniff out the rare software artefact of Jennifer points towards a general fetishization of the magic tipping point of the analogue/digital past –conjuring up a time when photography’s authenticity was still a battle to be fought. In a conversation with the artist at the appropriately ambiguous location of The Photographers Gallery shortly before his show opened, Dullaart emphasises the enduring pull of the image in his own practice. Describing the logic of the exhibition’s strategy, he sees the pasting of the Jennifer wallpaper as a “doubling” [1], or colonisation of his ongoing Jennifer experiment.

Dullaart’s Jennifer journey through the lexicon of data manipulation started when he embedded a secret stenographic message in the first re-appropriated images of Jennifer as a kind of “prize” for his growing online viral public. The first iteration(s) of Jennifer in Paradise explored the Internet’s opacity, highlighting the extent to which onscreen data is manipulated and controlled, enhanced or deformed. By celebrating and transporting the cyber-famous Jennifer into the gallery context in the form of selective editions, copies, or “abbreviations” of the digital, networked manipulation of the image, these artefacts act as both signifiers of the artists’ practice and as tempting photographic editions in their own right. A fact the artist is well aware of. However, the overarching social commentary implied in the freezing of this signifier of mass viral circulation is that the image became a coded Trojan horse for the prosumers’ 2.0 hypermarket as it was seeded, tracked mediated, remediated and mimetically distributed through the newly democratised digital commons.

It is in this mimetic gesture of versioning – a trope embedded in the very DNA of software development – that the artist does not just reference and make visible software’s surface gestures, but actually performs software’s versioning impulse, exposing it as a form of corporate cultural imperialism and spotlighting the newly negotiated role of authorship in the process. The artist’s persistent and persuasive disruption of the role of authorship is a common and recurring obsession running through his practice – from objects, to online queering of domain names, to his performances. A personal/impersonal example of this is played out in the exhibition by a row of seemingly innocuous family photographs. The series of family pictures from the 1980s are, according to Dullaart, the cleanest example of performative authorship. The photos were simply sent to Apple co-founder Steve Wozinak for him to sign and send back to the artist – resulting in the “re-authoring” of Dullaart’s childhood memories. This simple performance of capital control and authorship of so-called private identity is mainlined into Dullaart’s practice, and speaks to the artist’s core impulse: “this is exactly what I do – I take what isn’t public and I re-posses and reprocess these artefacts and re author them into a different spectrum”. [2]

In another act of ambiguous reverie of the commercial canon of software are the three pieces entitled Bill Atkinson demonstation drawing, (no.5, 12 and 18) hanging on the other side of the gallery, positioned against the Jennifer-tiled wallpaper. These drawings from the 23 stages of the first drawing made by Macpaint creator Bill Atkinson are printed in monochromatic hues sandwiched between photopolymer plates. These meticulously restored physical gestures of one of the first drawings executed by commercial software are particularly important for the artist. He sees this attempt at drawing made in the “strong consumer software” of Macpaint as a kind of totem or signifier of the emerging lexicon of the new canon in art history.

Beautiful fetishistic rubbery objects in themselves, the physicality of these works demonstrates the materially-dependent, performative intent in Dullaart’s practice. As these monochromatic objects react and change to UV light – hardening and cracking – any collector of his work needs to embrace the precarious temporality of the objects themselves. This is true of all of his work – including domain names, websites, his own online identity etc. and Dullaart emphasises that the conscious situating and staging of his works in the framework of time is one of the most vital components of his practice.

This animated relationship to instability and time- dependency is clearly demonstared in his player paino piece Feedback with Midi Piano Player at the heart of the exhibition. An algorithm interpreting polymorphic songs is played out through the grand piano in the gallery in an apparent circus-like celebration of the computer’s magical powers. However,as the recital unfolds, it is full of little mistakes – the songs are too complex for the computer to relay in a coherent feedback loop. For Dullaart, the inaccuracy and amateur quality of the computer/piano recital delivers a quasi -human quality of cuteness – an increasingly desirable quality in our popular technology, and an indication of the drive towards the synthetic anthropomorphism of digital objects and structures in general. This inevitably recalls Marx’s highly questionable use of anthropomorphizing comparisons of the commodity to children and women to underscore the “fetish character” [3] of commodities – the phantasmatic displacement of the sociality of human labour onto its products, as they appear to confront each other as if operating independent social lives of their own. In this sense, the “cuteness” in Dullaart’s piece might be seen as an intensification of commodity fetishism’s logic redoubled (like Jennifer) – as the viewer is connected to the unavoidable fantasy of fetishism, itself already an effort to find an imaginary solution to the irresolvable “contradiction between phenomenon and fungibility” [4] in the commodity form.

However, if this “cuteness” maintains fetishism’s overarching illusion of the object’s animate qualities – in this case the clumsy performance- at the same time it wants to deny what, in Marxian terms, these animated commodities articulate as “Our use-value may interest men, but is no part of us as objects…We relate to each other merely as exchange values.” [5]

Dullaart then shifts his attention to the main focus of the exhibition – the conscious construction and showcasing of his proposition of a new way of entering into a contract with our networked, hyper-published -selves: the balcony. The two physical balconies presented in Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators (one of which is accompanied by a digital ticker-tape text of his Balconism manifesto) are both visual prompts and, in a sense, demos, of Dullaart’s concept of balconisation. In direct acknowledgment of the hyper- mediated image of Julian Assange standing on the balcony of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London – Dullaart starkly illustrates this liminal, politically charged space where we bear witness to a clear slippage between UK and Ecuadorian territory. To Dullaart, the balcony represents a ‘space outside society’ [6], and this new space of public address marks a shift in responsibility in self-broadcast/publication in the digital commons and the social media sphere. According to Dullaart, we all need to recognise our position on the balcony in our hybrid public/private pathology and modus operandi of quasi-addictive self-broadcast.

On the balcony we should be ready to escape the warm enclosure of the social web, to address people outside our algorithm bubble. In the context of the show, the balcony is positioned as a higher order theory for how we should respond to the process of digitalisation as a whole, to how corporations and programmes structure our understanding of the world. We need to stand on our particular balcony ‘and choose to be out in public and we have to define cultural codes of how to do that’. [7]

What Dullaart’s exhibition Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators offers anew is an alternative proposition of spatial code through which to understand our steadily (re) negotiated locations of private and public space and the possibility of somewhere inbetween from which to enact a certain kind of everyday De Certeauian [8] tactic – the Balcony.

Dullaart’s solo exhibition ended at Carroll / Fletcher on 19th July 2014.

Featured image: Thomson and Craighead, Here (2013)

Visiting Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead’s survey exhibition, Never Odd Or Even, currently on show at Carroll / Fletcher Gallery, I found myself confronted with an enigma. How to assemble a single vision of a body of work, impelled only by the dislocated narratives it offers me? ‘Archaeology’ is derived from the Greek word, arche, meaning ‘beginning’ or ‘origin’. The principle that makes a thing possible, but which in itself may remain elusive, unquantifiable, or utterly impervious to analysis. And so it is we search art for an origin, for an arising revelation, knowing full well that meaning is not something we can pin down. Believing, that the arche of a great work is always just about to take place.

In an essay written especially for the exhibition, David Auerbach foregrounds Thomson and Craighead’s work in the overlap between “the quotidian and the global” characteristic of our hyperconnected contemporary culture. Hinged on “the tantalising impossibility of seeing the entire world at once clearly and distinctly” [1] Never Odd Or Even is an exhibition whose origins are explicitly here and everywhere, both now and anywhen. The Time Machine in Alphabetical Order (2010), a video work projected at the heart of the show, offers a compelling example of this. Transposing the 1960 film (directed by George Pal) into the alphabetical order of each word spoken, narrative time is circumvented, allowing the viewer to revel instead in the logic of the database. The dramatic arcs of individual scenes are replaced by alphabetic frames. Short staccato repetitions of the word ‘a’ or ‘you’ drive the film onwards, and with each new word comes a chance for the database to rewind. Words with greater significance such as ‘laws’, ‘life’, ‘man’ or ‘Morlocks’ cause new clusters of meaning to blossom. Scenes taut with tension and activity under a ‘normal’ viewing feel quiet, slow and tedious next to the repetitive progressions of single words propelled through alphabetic time. In the alphabetic version of the film it is scenes with a heavier focus on dialogue that stand out as pure activity, recurring again and again as the 96 minute 55 second long algorithm has its way with the audience. Regular sites of meaning become backdrop structures, thrusting forward a logic inherent in language which has no apparent bearing on narrative content. The work is reminiscent of Christian Marclay’s The Clock, also produced in 2010. A 24 hour long collage of scenes from cinema in which ‘real time’ is represented or alluded to simultaneously on screen. But whereas The Clock’s emphasis on cinema as a formal history grounds the work in narrative sequence, Thomson and Craighead’s work insists that the ground is infinitely malleable and should be called into question.

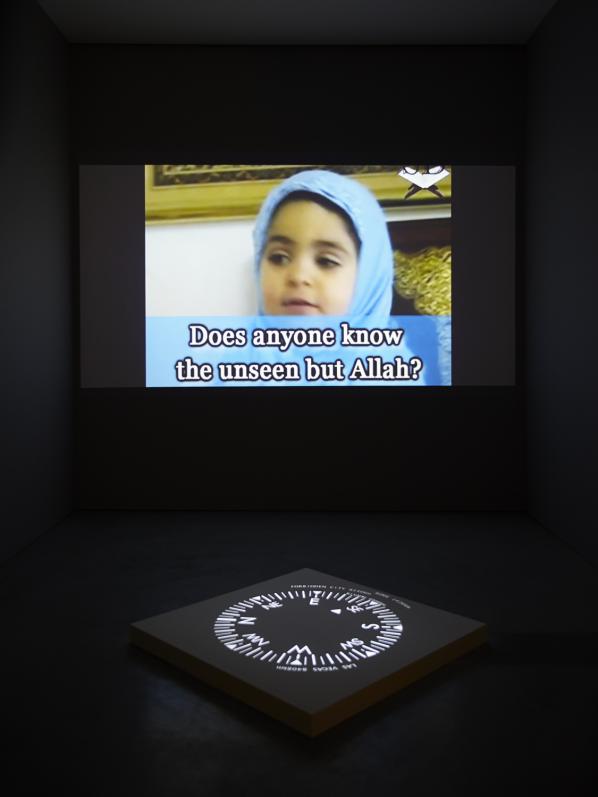

Another work, Belief (2012), depicts the human race as a vast interlinked, self-reflexive system. Its out-stretched nodes ending at webcams pointing to religious mediators, spiritual soliloquists and adamant materialists, all of them searching to define what it means to be in existence. Projected on the floor of the gallery alongside the video a compass points to the location each monologue and interview was filmed, spiralling wildly each time the footage dissolves. Each clip zooms out of a specific house, a town, a city and a continent to a blue Google Earth™ marble haloed by an opaque interface. Far from suggesting a utopian collectivity spawned by the Google machine, Belief once again highlights the mutable structures each of us formalise ourselves through. As David Auerbach suggests, the work intimates the possibility of seeing all human kind at once; a world where all beliefs are represented by the increasingly clever patterns wrought through information technology. Instead, culture, language and information technology are exposed as negligible variables in the human algorithm: the thing we share is that we all believe in something.

Never Odd Or Even features a series of works that play more explicitly with the internet, including London Wall W1W (2013), a regularly updated wall of tweets sent from within a mile of the gallery. This vision of the “quotidian” out of the “global” suffers once you realise that twitter monikers have been replaced with each tweeter’s real name. Far from rooting the ethereal tweets to ‘real’ people and their geographic vicinity the work paradoxically distances Thomson and Craighead from the very thing twitter already has in abundance: personality. In a most appropriate coincidence I found myself confronted with my own tweet, sent some weeks earlier from a nearby library. My moment of procrastination was now a heavily stylised, neutralised interjection into Carroll / Fletcher gallery. Set against a sea of thoughts about the death of Margaret Thatcher, how brilliant cannabis is, or what someone deserved for lunch I felt the opposite of integration in a work. In past instances of London Wall, including one at Furtherfield gallery, tweeters have been contacted directly, allowing them to visit their tweet in its new context. A gesture which as well as bringing to light the personal reality of twitter and tweeters no doubt created a further flux of geotagged internet traffic. Another work, shown in tandem with London Wall W1W, is More Songs of Innocence and of Experience (2012). Here the kitsch backdrop of karaoke is offered as a way to poetically engage with SPAM emails. But rather than invite me in the work felt sculptural, cold and imposing. Blowing carefully on the attached microphone evoked no response.

The perception and technical malleability of time is a central theme of the show. Both, Flipped Clock (2009), a digital wall clock reprogrammed to display alternate configurations of a liquid crystal display, and Trooper (1998), a single channel news report of a violent arrest, looped with increasing rapidity, uproot the viewer from a state of temporal nonchalance. A switch between time and synchronicity, between actual meaning and the human impetus for meaning, plays out in a multi-channel video work Several Interruptions (2009). A series of disparate videos, no doubt gleaned from YouTube, show people holding their breath underwater. Facial expressions blossom from calm to palpable terror as each series of underwater portraits are held in synchrony. As the divers all finally pull up for breath the sequence switches.

According to David Auerbach, and with echoes from Thomson and Craighead themselves, Never Odd Or Even offers a series of Oulipo inspired experiments, realised with constrained technical, rather than literary, techniques. For my own reading I was drawn to the figure of The Time Traveller, caused so splendidly to judder through time over and over again, whilst never having to repeat the self-same word twice. Mid-way through H.G.Wells’ original novel the protagonist stumbles into a crumbling museum. Sweeping the dust off abandoned relics he ponders his machine’s ability to hasten their decay. It is at this point that the Time Traveller has a revelation. The museum entombs the history of his own future: an ocean of artefacts whose potential to speak died with the civilisation that created them. [2] In Thomson and Craighead’s work the present moment we take for granted becomes malleable in the networks their artworks play with. That moment of arising, that archaeological instant is called into question, because like the Time Traveller, the narratives we tell ourselves are worth nothing if the past and the present arising from it are capable of swapping places. Thomson and Craighead’s work, like the digital present it converses with, begins now, and then again now, and then again now. The arche of our networked society erupting as the simulation of a present that has always already slipped into the past. Of course, as my meditation on The Time Traveller and archaeology suggests, this state of constant renewal is something that art as a form of communication has always been intimately intertwined with. What I was fascinated to read in the works of Never Odd Or Even was a suggestion that the kind of world we are invested in right now is one which, perhaps for the first time, begs us to simulate it anew.

Anonymous, untitled, dimensions variable is the title of a show by 0100101110101101.ORG (Eva and Franco Mattes) at Carroll/Fletcher gallery in London from 13th April to 18th May 2012. Or at least it was. The title changes each day based on submissions to a blog (http://exhibitiontitlechange.tumblr.com/). The new titles have been printed out and displayed on the wall to the left as you walk in to the gallery.

You don’t expect this kind of playful intersection of the virtual and the real in a gallery off of Oxford Street, across from Soho, opposite other new galleries. Carroll/Fletcher’s glass-fronted welcomingly brutalist interior says “serious contemporary art space”. Inhabiting such a space presents a challenge to net and digital art that must be met with careful presentation and considered curation.

Through the glass front of the gallery, and as you enter, you see a sculpture or assemblage of a (stuffed) cat trapped in a birdcage by a (stuffed) canary (Catt, 2010). The cat has suffered Epic Fail as the Internet would say, and did in the meme image that the sculpture is based on. It’s a comic and unnerving object even without the extra layers of reference provided by the original meme and the knowledge that it was originally presented as a fake Maurizo Cattelan sculpture. It is art with its roots in the net that can stand on its own without that context. Its companion piece, Rot, 2011, is a fake Dieter Roth sculpture consisting of detritus in a glass jar on a plinth against the far wall. 0100101110101101.ORG briefly inserted it into the Wikipedia page on Roth, and the fact that its materials were all ordered via the Internet drives home just how commonplace this has become.

Both are given the room they need to work as objects in a gallery. Neither originates in itself as net art, more in 0100101110101101.ORG’s history of tricksterism and transgression. These are concerns that are easily linked to net culture, possibly too easily on the part of the reviewer, but it is telling that they are the works that the show opens with. They physically establish the playful appropriation and hyperreality that is the basis of much of 0100101110101101.ORG’s work.

Pride of place in the first room of the gallery goes to the projection The Others, 2011, 10,000 digital photographs (supposedly) copied without authorization from the folders of computers used by people on a peer-to-peer filesharing network that 0100101110101101.ORG used to distribute their own work. These are private images, projected at an angle and slightly across the corner. Configure your peer-to-peer filesharing client wrongly and it shares all the files in the folder you share. Including the images of you naked, drunk, lonely, partying, or whatever else you wouldn’t post anywhere a future employer might find them.

In the next, smaller, room is Colorless, odorless and tasteless, 2011. It is an old-fashioned car racing video arcade game retro-fitted with a petrol engine that starts up when you insert a coin and revs as you press the pedal to accelerate the virtual car on the screen, filling the (sealed…) room with carbon monoxide. Combining the virtual made physical of Catt and the moral impact of The Others, it is the most immediately dangerous artwork I’ve ever had to review.

Moving into the larger room at the back of the ground floor of the gallery, the video No Fun, 2010, is the most shocking piece in the show. Franco Mattes pretending to hang hineself on the random Internet webcam video chat switchboard Chatroulette is one thing, but the reactions of other Chatroulette users as they connect and see him apparently hanging there is quite another. Some laugh, some jeer, only one I watched displayed any lasting concern. This is the moral and aesthetic flipside of The Others.

Reenactments, 2007, is my aesthetic and technical favourite piece in the show. Videos of canonical performance art pieces being re-enacted by Eva and Franco’s Second Life avatars are displayed on CRT monitors arranged at floor level surrounded by the cables and adapters used to play back the video from SD cards. It’s much easier for an avatar to remain still as a “Singing Sculpture” than it is for a human being, making it even stranger, and Marina Abramovic’s “Imponderabilia” works much better with impossibly buff avatars than with mere naked human models stood in a doorway. It exquisitely foregrounds the social mediation of Second Life and its players self-presentation. A large cartoon wolf squeezes through between the naked avatars, their polygons intersecting. A vampire attempts to fly over them but hits the bounds of the architecture. The crowd in the background chat and bide their time. The virtual intensifies the real, out-doing and critiquing its appropriated source material.

Stolen Pieces, (1995, made public 2010) claims to move beyond fakery and unauthorized copying to physical appropriation. Stolen physical fragments of canonical postmodern artworks (Duchamp, Warhol, Koons, Rauschenberg) are displayed like forensic evidence, protected in small plexiglass containers, accompanied by large photographs of them and by documentary evidence of their theft. There’s no statute of limitation on theft in the UK, and damaging artworks shouldn’t be applauded. But it’s a daring performance and a concrete critique of the fetishism that lies at the heart of the art market and the institutions that help drive its value.

Following the brutalist concrete staircase to the basement reveals My Generation, 2010, a smashed but still working early-2000s PC lying on the floor. On its monitor, that appears to have fallen on its side, show video clips of computer game players giving in to and venting their frustration at the games they play. This isn’t the kind of image of yourself you want as your lasting monument on the Internet. Gathered together, like the images in The Others and the videos in No Fun, they again form a summation of an aspect of society and our visual environment that could not be achieved with such immediacy by other means. And the clear space and architectural solidity of the gallery again help to put a different emphasis on the material than if it was encountered on the web.

The wall-filling video projection of Freedom, 2011, records Eva’s attempts to plead with the players of networked First Person Shooter computer games not to kill her character. Touch-typing might have helped, but even when Eva manages to type long enough to explain that she’s an artist, or to ask people not to shoot, the social and game logic of the virtual world mean that her character is executed again and again, the screen shifting to third person as her avatar moves out of her control in death. Like No Fun, there is a core of callousness to these Internet interactions, and like My Generation they are unexpectedly preserved and presented for contemplation.

The final piece in the show is the documentary Let them believe, 2010, a video record of 0100101110101101.ORG’s Tarkovsky-haunted journey into Chernobyl’s “Exclusion Zone” in order to recover part of a fairground ride to turn into Plan C, 2010. Bringing part of the ride to life in a place where people can enjoy it is an effective and resonant symbolic resolution of the kind that art more than any other mode of human endeavor can provide.

0100101110101101.ORG’s work presented physically has more than enough presence to fill the gallery and benefits from the space and the considered curation afforded it here. Some of the work is more physical than virtual and vice versa, sometimes the ethics of the work place 0100101110101101.ORG as the villain sometimes as the victim, and sometimes the work is performance whereas other times it is assemblage. I mention this to point out both the strong themes to the work and how individual the effect of each piece is.

Net art in the gallery might seem a category error, like museum postal art. Or it might seem a commodity, like auctions of land art documentation. But net art is transitioning from being the contact language of artworld emigrants learning the net’s protocols to the contact language of net emigrants learning artworld protocols. 0100101110101101.ORG have made art of these encounters from the start, and have always been as at home in the gallery as on the net.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.