White Heat Cold Logic

British Computer Art 1960-1980

Edited by Pal Brown, Charlie Gere, Nicholas Lambert and Catherine Mason

ISBN 9780262026536

MIT Press 2008

This is the third and last in a series of reviews of the results of the CACHe project. The first review was of the V&A’s show and book “Digital Pioneers“, the second was of Catherine Mason’s “A Computer In The Art Room”. Where “A Computer In The Art Room” concentrated on the history of art computing in British educational institutions up to 1980, “White Heat Cold Logic” gives voice to the individuals who made art using computers in that period more generally.

Charlie Gere’s introduction explains the source of the book’s title, referring to the British Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s famous 1963 speech that a new Britain would be forged in the white heat of the scientific and technological revolution. Gere provides an overview of the history of art computing in the era that may be familiar from “A Computer In The Art Room” which is much needed, for it provides useful context for what follows in this volume. He also argues for the value and interest of the history of art computing, in terms that make it clear for academia.

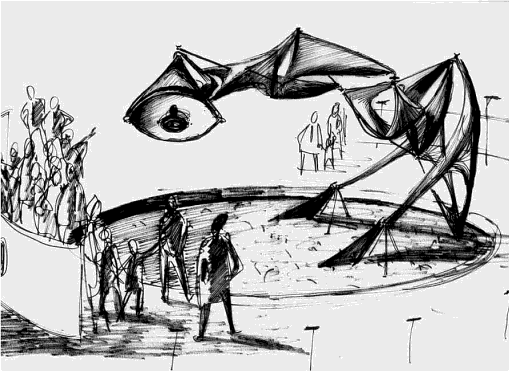

Roy Ascott describes the emergence of pre-computational art informed by cybernetics, systems theory and process against the background of the emergence of “Grounds Course” art education. Adrian Glew documents Stephen Willats’ use of computing in the processes of his art of cybernetic social engagement, the first but not the last more mainstream British artist to appear. John Hamilton Frazer describes the unrealised interactive architecture of the 1960s “Fun Palace” and 1980s “Generator” and of the technology and social legacies of these nonetheless influential projects.

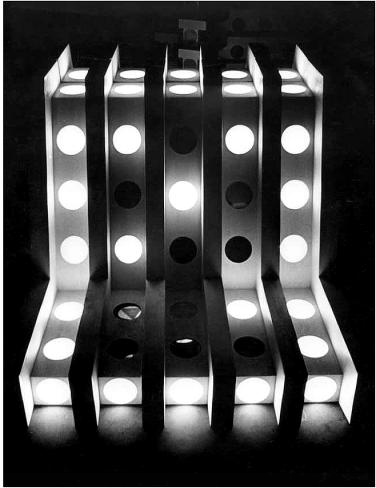

Maria Fernandez puts the figure of Gordon Pask centre stage. As John Lansdown (to whom this book is dedicated) emerged as a major figure behind educational arts computing in “A Computer In The Art Room”. Gordon Pask also emerges in this volume as the cybernetic prophet of the 1960s, mentioned by many in the early essays in this book. His own interactive theatre and robotic mobiles complement his involvement in planning the Fun Palace and as a source of ideas and support for more projects.

Jasia Reichardt provides a theoretical and practical insight into the genesis of her foundational “Cybernetic Serendipity” show at the ICA in 1968 and considers what came next. Brent Macgregor provides an outside view of the same. Neither attempts to mythologize this much mythologized show, the reality of its achievements is more than impressive enough.

Edward Ihnatowicz is the subject of two essays, one with tantalising images of preparatory and documentary material by Aleksandar Zivanovic and an insightful but more personal essay by Richard Ihnatowicz. Hopefully his reputation will continue to increase towards the level it deserves.

Richard Wright follows the ideas of Constructivist art into Systems Theory, which alongside cybernetics is one of the guiding ideas of the art of the period overdue for rediscovery both within art computing and more generally.

Harold Cohen remembers the origins of his “AARON” painting program in a tale of the struggle of art against bureaucracy. Tony Logson’s tale is surprisingly similar, although his systems-based art is very different from Cohen’s cognitively-inspired forms. Simon Ford reveals Gustav Metzger’s involvement with early computer art and with the Computer Arts Society (CAS). CAS also feature large in Alan Sutcliffe’s description of his computer music compositions, one of many essays that left me wishing I could see the code and experience the art as well as reading about it.

George Mallen also touches on CAS, and on Pask’s System Research Ltd. as he explains the art and business of the production of the unprecedented environmentalist interactive multimedia of the “Ecogame”. The Ecogame is one of many works in the book that people simply need to know about. Doron D. Swade makes the idea of the “two cultures” of art and technology that came together for the Ecogame more explicit in an attempt to recover the art of the Science Museum’s first computing exhibit.

Malcolm le Grice and Stan Heyward each describe the institutional travails of making some of the first computer animation in the UK. Catherine Mason draws together the history of many of the institutions already mentioned in what is both a recap and an extension of the history she presented in “A Computer In the Art Room”. Stephen Bury and Paul Brown bring the influence of the Slade to the fore in their chapters, revealing the Slade as an important piece in the puzzle of British Computer Art.

Stephen Scrivener, Stephen Bell, Ernest Edmonds and Jeremy Gardiner each describe their personal artistic journeys through the era of FORTRAN and flatbed plotting, illustrated by images of their work that again made me wish I could also see the code. Graham Howard describes how conceptual artists Art & Language didn’t use a university computer to generate the 64,000 permutations of one of their “Index” projects of the 1970s, instead gaining access to a local produce distribution company’s mainframe across several weekends.

The different strands of technology, institutions, ideas and economics are all drawn together in John Vince’s history of the PICASO graphics library, which spread from Middlesex Polytechnic to many other educational institutions and the successor to which, PRISM, was used to make the first logo for Channel 4.

Brian Reffin Smith makes clear, artists were as affected by the idea of computing as by computers themselves, especially when they didn’t have access to them. The Fun Palace was influential despite never being realized, Senster was influential despite being lost. It is important to realize just how limited access to computing machinery was in the era covered by the book, and to recognize how ideas of computing and its potential were part of the broader intellectual environment of the time.

Finally, Beryl Graham’s postscript covers the history of UK arts computing after 1980. I lived through some of the period covered and I recognise Graham’s description of it. The critical irony that she identifies in UK net.art and interactive multimedia is of key importance to its art historical value. Although I would question how uniquely British this is, the UK certainly took it as a baseline. As with Gere’s introduction, Graham presents the case for art computing in a way that the art critical mainstream should not just be able to understand but should be inspired by. Cybernetics, systems theory, environmentalism, socialisation, the content of conceptual art, and the political concerns and developments of the Cold War all illuminate and are in turn illuminated by this history.

For a book about art computing it is frustrating how little art and source code is illustrated in the book. Much work has been lost of course, and “Digital Pioneers” does illustrate art from this period. But for preservation, criticism and artistic progress (and I do mean progress) it is vital that as much code as possible is found and published under a Free Software licence (the GPL). Students of art computing can learn a lot from the history of their medium despite the rate at which the hardware and software used to create it may change, and code is an important part of that.

White Heat, Cold Logic presents hard-won knowledge to be learnt from and built on, achievements to be recognised, and art to be appreciated. Often from the people who actually made it. What was previously the secret history or parallel universe of art computing can now be seen in context alongside the other avant-garde art movements of the mid-late 20th century. I cannot over-emphasise the service that CACHe has done the art computing community and the arts more generally by providing this much needed reappraisal of early arts computing in the UK.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.