Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Space Invaders

Tomohiro Nishikado’s classic videogame Space Invaders from 1978 can be seen as a metaphor for the Cold War and the fears for an approaching nuclear war. An extraterrestrial army are marching rhythmic and increasingly closer to Earth. Only a lone cannon stands between the intergalactic monsters and the total annihilation of mankind. The lonely hero struggling against evil is a theme that we recognise from myths, films and books. Space Invaders with its clear and pedagogical symbolic language has inspired several contemporary artists to describe the eternal struggle between good and evil in our time.

In the British artists Thomson & Craighead version Triggerhapppy the enemy aliens are replaced with quotes taken from the French philosopher Michael Foucault’s essay “What is an author?” “Triggerhappy” is a work that explores the relationship between hyper-text, author and reader. What is a writer, or rather, who is the artist when we are dealing with interactive art in the form of a videogame? Is it Tomohiro Nishikado who created the original game or is it Thomson & Craighead that have modified the game or the player that are playing the game or maybe the computer that creates and interprets the text (the code) that make the game appear on the screen?

After the 11th of September the world suddenly saw a new major enemy, international terrorism. In a modernized version of “Space Invaders”, the artist Douglas Edric Stanely located the scenario in the game to the Twin Towers in New York, which was destroyed during the terrorist attack on 11th September 2001. In Stanley’s version titled the invaders, you have to fight against the hostile aliens before they completely destroy the two towers. The classic struggle between good and evil continues, the game concept is the same as in the original but the scenario and the metaphoric meaning of the aliens has changed.

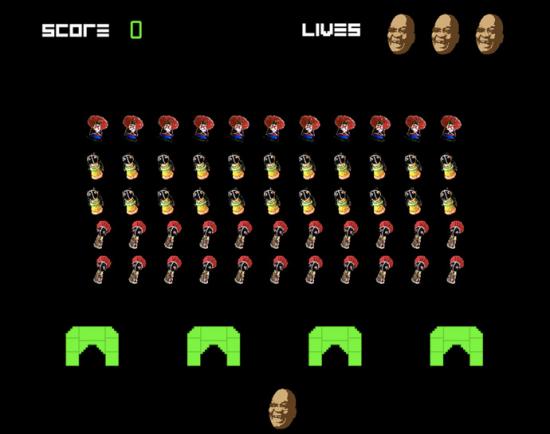

The struggle between good and evil can also be found in other areas of our society, for example in class and gender struggle. In the South African photojournalist Nadine Hutton’s version Skirt-Invaders the main character in the game is Jacob Zuma, South African president since 2009. Zuma has been quite controversial because he is a polygamist and has expressed his doubt about the dangers of AIDS. In the game Zuma you have to shoot down a never-ending stream of virgins from the Zulu tribe. Will the president succeed to shoot down any threatening scandals before they land on the ground? Hutton’s work is an example how a well-known videogame can be used for political purposes and be both entertaining and still very critically at the same time.

The term mash-up, which is frequently used today, could be described as a form of digital collage. Ryan Sneider has created mash-ups by combining images from various sources, in this case photographs from Life magazine’s archives and videogames. The photomontage Duck Hunt / Space Invader shows a bird hunter with a dog, but it is not birds the hunter aims for, instead it is the famous monsters from the “Space Invaders”. Those who played videogames in the 70 – and 80’s will probably remember the game “Duck Hunt”, where you could shoot ducks that flew up out of the reeds and your faithful dog then ran to fetch them. Sneider has combined the two game ideas, one composed of a photo of a true hunter with a dog and the second of digital graphics from the videogame “Space Invaders”. The work discusses the boundaries between the real and digital world. What will happen when these two worlds become more integrated and the borders are increasingly blurred?

Finally we have to mention the artist, who personifies the game, the French street artist who hides behind the pseudonym Space Invader. His main art project consists of invading various cities around the world and putting up small mosaics of characters from videogames as “Space Invader”. For each successful invasion, he collects points, and the whole art project is described on his website as a reality game. Like other forms of street art “Space Invader” is an ongoing battle about the public space. With help of popular culture Space Invader tries to infiltrate the commercial forces that almost have total monopoly on the imagery that appears in our public spaces. The aliens, in form of small mosaics, become a force that can not be defeated when they are spreading all over the world. A important part of the game “Space Invaders” is that you cannot win, you can certainly come to the high score list, but you can never defeat the aliens, they are instead coming in faster and faster each time they are shot down. It’s obviously a dystopian world view we meet in the videogame, but if we look at it from the artist Space Invaders point of view, it’s rather something positive. The art is a force that will not be stopped. The invasion has just begun and the struggle between good and evil continues…

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Pong. Part 1 by Mathias Jansson.

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Tetris. Part 2 by Mathias Jansson.

The legend says it was when the Japanese game developer Toru Iwatani took a slice of his pizza that the yellow game character Pac-Man appeared before him. In Pac-Man, we find a restless character hunting around in life’s mazes constantly seeking for pills to satisfy his insatiable desire. Meanwhile the ghosts of anxiety are tracking him down. What many players don’t realize are that the game also contains an unanswered philosophical-existential question. Where is actually Pac-Man for the short period of time when he escapes into the left or right end of the maze and after a short time pop up on the other side of the maze?

In Martina Kellner’s work “Pac-Man Time Out”, which was showed at the exhibition A MAZE in Berlin 2009, Kellner had created short video clips that investigated what Pac-Man actually did in the short time he was away from the monitor. In one clip, we find him at the airport queue with Ms. Pac-Man ready to board. Perhaps they are planning to take a holiday away from the busy videogame environment? One thing is for sure, Pac-Man does no appear in contemporary art as much as his colleagues from other classic games as Space Invader, Pong and Super Mario.

Like many 8-bit characters Pac-Man is well represented in street art and design. For example the American street artist Katie Sokoler staged a real Pac-Man game in her quarters. But it is quite unusual with installations, machinima or Art Games in which Pac-Man has the lead role. This is a bit odd considering how famous Pac-Man is among the general public. The French artist François Escuillie has even created a paleontological reconstruction of Pac-Man’s skull and the Swedish artist Johan Lofgren has in his new colour series “Confessions of a Color-Eater” taken with the colour “Ms. Pac -Man-yellow “, but despite this there are few interactive artworks based on Pac-Man.

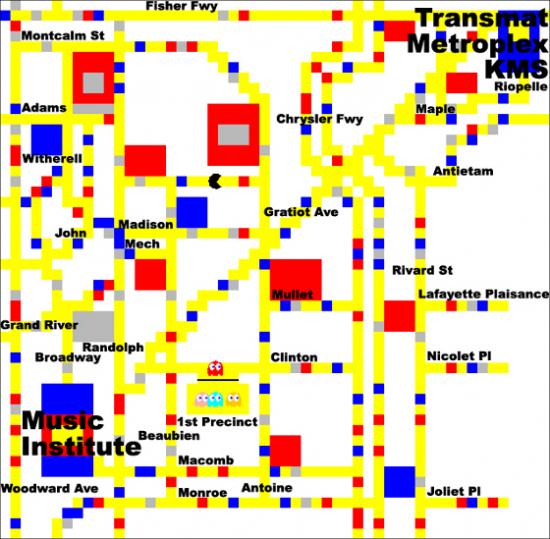

Two exceptions are in any case worth highlighting: the “Pac-Mondrian” and “Eggregore”. “Pac-Mondrian” was created in its first version in 2002 by the Canadian artist group, Price Budgets Boys and is described as a mix of Piet Mondrian, Pac-Man and Boggie Woggie music. The board consists of Piet Mondrian’s painting “Broadway Boogie Woogie” (1942-43), which in its turn is inspired by Manhattan’s street grid and boogie woogie music. The videogame works with the same principle as a normal Pac-Man game except that the maze is a painting by Piet Mondrian. Price Budget Boys have also created three sequels: “Detroit Techno” (2005), “Tokyo Techno” (2006) and “Toronto Techno” (2006). The labyrinths in the new versions are created by stylized street grid from each city, executed in the style of Piet Mondrian. And in the name of equality, you play as Ms.Pac-Man in these versions. For those who have followed previous articles in this series, will recognize that there is a similarity between “Pac-Mondrian” and the Danish artist Andre Vistis works “PONGdrian v1.0”, in which Vistis combined the videogame PONG with Mondrian’s paintings.

Antonin Fourneau & Manuel Braun’s work “Eggregore” is a social video game in which eight players, each with its own control will try to collaborate and steer Pac-Man through the maze. It may sound like an old teamwork workshop with a twist. Eight wills and strategies must collaborate to succeed with the mission. “Eggregore” is a Greek word which is associated with occultism and means a collective mind. The question that Fourneau and Braun is asking is: Can multiple individual game strategies together create a stronger and better collective player or will it just be chaos when the different games strategies are pulling in different directions? In the video game world, there are many examples of online worlds like World of Warcraft, where player successfully work together in clans or guilds in order to achieve higher goals in the game. It has even become an asset in your CV to show that you have played World of Warcraft and that you can lead and work together with other players to achieve different goals. Pac-Man, however, seems to be a rather greedy individualist who only thinks of himself in the video game world. And perhaps it is this self-absorption with himself taht prevents the game from breaking through as a major theme in contemporary Game Art?

Pac-Mondrian:

http://www.pbfb.ca/pac-mondrian/

Eggregore:

http://liftconference.com/eggregor8

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Pong. Part 1 by Mathias Jansson.

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Tetris. Part 2 by Mathias Jansson.

Videogame appropriation in contemporary art: Space Invaders. Part 3 by Mathias Jansson

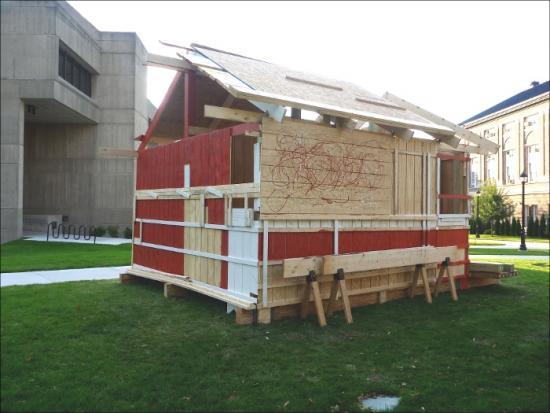

All Raise This Barn – a group-assembled public building and/or sculpture.

“Artists MTAA are conducting an old-fashioned barn-raising using high-tech techniques. The general public group-decides design, architectural, structural and aesthetic choices using a commercially-available barn-making kit as the starting point.” -MTAA

Eric Dymond: Could you give me a brief history of MTAA?

T.Whid: Mike Sarff (M.River of MTAA) and I met in college at the Columbus College of Art & Design in Columbus, OH. We both separately moved to NYC in 1992 and started collaborating as MTAA in 1996 first on paintings and then moving on to public happenings and web/net art. We’ve been collaborating since, showing our work via our websites at mteww.com and mtaa.net. We’ve earned grants and commissions from Creative Capital, Rhizome.org and SFMOMA and shown at the New Museum, 01SJ Biennial, the Whitney Museum and Postmasters Gallery.

ED: The All Raise This Barn project uses one community to design and another to construct. Barn raising is itself a communal activity, drawing out the best in people and providing a place of sustenance for the Barn owner. How did you come to use a Barn Raising as the central performance subject?

M.River: From the start, Tim and I have been interested in how groups and individuals communicate. How do we speak to each other? What rules do we use? How does communication fail or how can it be disrupted? What is the desire that engines (TW: controls?) all of this – and so on. This interest in exchange is what attracted us to the Internet as a site for art in the beginning.

Along with communication as text, speech or image, we like to use group-building as a method for working with non-verbal communication. We’ve built robot costumes, car models, aliens and snowmen with large and small groups. It’s a type of building that is intuitive and open to creative improvisation. This kind of intuitive building is heightened by placing a time constraint on the performance. In the end it’s not about the end object, which we always seem to like, but more about the group activity.

So, at some point we began to think how large can we do this? A barn-raising seemed like the next level. It’s bigger than human scale and contains a history of group-building. Barns also have a history of being social spaces. Your home is your world but the barn is your dance hall.

ED: Did you envision it as a community event from the beginning?

MR: Yes. An online community, a physical community and a community that overlaps the two.

ED: It’s a hybrid work that draws upon some important conceptual precedents. The instructional aspect takes Lewitt and turns the strict instructions he uses upside down by allowing online decisions to drive the design. Did you find the responses to the online polling surprising?

MR: Yes and no. Like the other vote works we have produced, Tim and I set up how the polls are worded and run. So, even though we try to keep the process as open as possible, the nature of how people interact is somewhat fenced in. Even with a fence, people will find a way to move in strange directions or break the fence. It’s not that we think of the surprising answers as the goal of the work, but it is an important part of the process.

ED: There is also the performance aspect which I find exciting. The performance from both events are well documented. Were there any concerns regarding the transfer of the polls instructions to physical space?

MR: We had the good fortune of doing the work in two sections. When Steve Dietz commissioned ARTBarn (West) for the 01SJ Out of the Garage exhibition, we spoke about the sculpture as a working prototype for how a large pile of lumber could be group-assembled in a day with direction from Internet polling. From this prototype we then had a model for how to go about ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC.

Tim and I had a few loose ground rules on how to approach the translation. One was that we would leave some things open to the interpretation of the crew. Another was that both Tim and I had our favorite poll questions that we tended to focus on. It was impossible to do everything as some polls conflicted with other but some details liked ghosts, dripped paint and open walls seemed to call out to us.

Kathleen Forde, who commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC, spoke about these details as where the work became more than the sculpture. The small details held the whole process – material, design polls, and performance together.

ED: I think this comment on the details is right. On first glance there is a fun, open appeal to the work. But when you look at the overall project and how the different phases are tied together it becomes really complicated in the mind of the spectator. There are also different definitions of spectator in this work. The spectator who answers the poll, the spectator on the net who is grazing through the documentation, the ones who engage in the physical construction and those who witness the completed barn. It’s not a simple piece when we perform a detailed overview. Did you think about the various types of spectator that would spin off the project? Were the possible roles for the spectator considered after the fact or were they part of the planned concept?

MR: The “ideal spectator” thought first came up for us in a project called Endnode (aka Printer Tree) in 2002. For this work, we built a large plywood Franken-tree with a set of printers in the branches and a computer in the trunk. We then built a list-serve for the tree as well as subscribed it to a few list-serves. When people communicated with the tree, the text was printed out in the exhibition space. At first we talked about the ideal viewer as one who communicated with it online and then saw that communication in the physical space or vice versa.

Now I feel that the ideal spectator hierarchy is not as important and possibly limiting. Each experience should be whole as well as point to the larger aspects of the work. People can come in and out of the work on different levels. You voted. You followed the performance documentation. Are you missing an experience if you did not build with us or see the results? Yes, an activity is missed. Can you experience that activity thorough documentation. Somewhat. Are you going to have a better understanding of the work. Probably not. Even for me, some aspect of the work will not be experienced. In Troy, they are programing it as a meeting place now that is it is built.. When they are done with it, they will dismantle it and rebuild it elsewhere as a work space.

I say all this even though it is interesting to me that a work can move in and out of levels of viewer experience. I’m not sure as to the draw of it yet but I do not feel it is about an cumulative effect.

TW: Since Endnode I’ve always liked the idea of an art work that exists in multiple (but overlapping) spaces with multiple (but overlapping) audiences. With our pieces Endnode, ARTBarn and Automatic For The People: () there are 3 distinct (but overlapping) audiences: the online audience, the audience in the physical space and the (select few member) audience that experiences the entire thing.

ED: It’s that opening of possibilities that makes this ultimately a networked piece on many different levels. I find the idea of two barns, a few thousand miles apart yet linked by common purpose really intriguing. I’m talking about the whole set of experiences, not just the physical space of the barn. There’s a collapse of Geographic distance for the community and a richer experience because of that. Was the project conceived as two distinct locations or was that a fortunate turn of events?

MR: Fortune. Kathleen Forde, commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC then Steve Dietz commissioned the beta version for the 01SJ “Out of the Garage ” exhibition. Everyone liked the idea of the work arching across time and location. We all also liked the idea that the materials would be reclaimed after it stopped being a sculpture. For me, the reclaimation of the materials to use for a functional structure is the final step of the work.

ED: As the final step, the reclamation removes the common space where the community currently shares the sculpture. Does this mean you are going to use the online documentation as the artifact, coming full circle to where the piece began? Is it important to you that the communal memory will share this role?

TW: Yes, the documentation is the artifact. The barn structure or sculpture itself had been conceived as being physically temporary from the beginning.

ED: Thanks to both of you for your time and for this work.

Introduction:

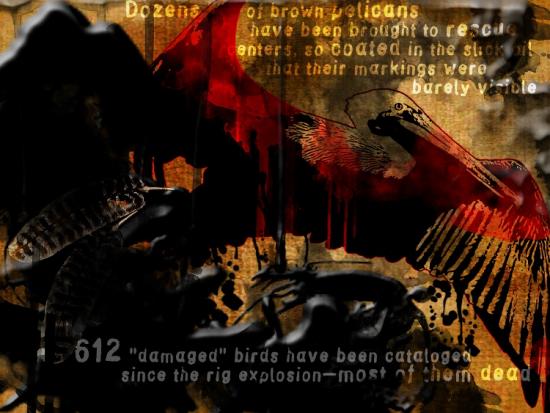

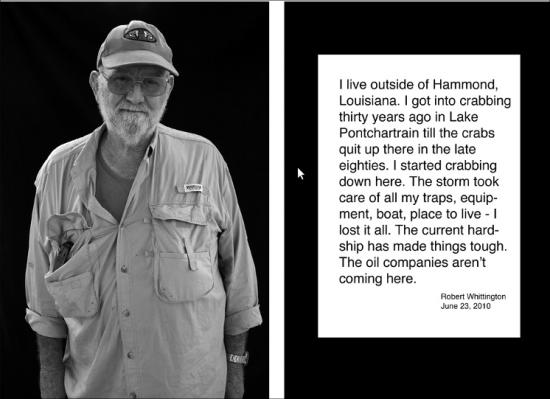

As media attention wanes, the impact of British Petroleum’s Deep Horizon, off-shore drilling disaster continues to unfold. Artists worldwide respond to this new ecological catastrophe in a group show organized by Transnational Temps, an arts collective exploring the interstices of art, ecology and technology. For Andy Deck, one of the founding members of Transnational Temps and the curator of the show, “After a decidedly unsuccessful round of climate negotiations in Copenhagen, the disaster in the Gulf of Mexico frames this exhibition of Earth Art for the 21st Century.”

Now hidden from view by BP’s media campaigns and other de facto censoring actions, the images of oil-covered birds struggling to breathe and fly, oil and dispersant-coated fish, dolphins and whales washing up dead while most sink to the ocean floor, have all but vanished. Partially filling the void are the artists showing here who are recreating topographies: mapping the course of a deadly shadow over our shores and waters; and reinterpreting the sea, its rising levels and largesse, before the vicissitudes of man and nature. Transnational Temps.

———-

Spill >> Forward by Transnational Temps describes itself as an Online Exhibition. It is a website containing images and other media on the theme of oil spills. Some of the images were shown at the MediaNoche gallery from July 30th – November 19th, 2010, with works added or removed so it isn’t just an online catalogue of a meatspace show.

The front page of the site warns that you’ll need a browser that supports HTML5 video and audio, and states that you can view it using patent-free media codecs. From a Free Software and Free Culture point of view this is excellent, your ability to view the art is not restricted by anyone else’s technological or legal machinations. This is also good from an artistic point of view. The software used to view the art can be run and maintained by anyone, making it more accessible, exhibitable and archivable. But this freedom doesn’t extend into the work itself. some of the art uses proprietary software, and none is under a free Creative Commons licence.

The image on the front page, or possibly the image exhibited at the entrance to the exhibition, is not advanced HTML5 video or canvas tag animation but an animated GIF. A Muybridge-ish series of still images of a pelican in flight flickers rapidly up and down as it descends behind an iridescent oil slick that solarizes the bottom half of the image. It’s an effective image in itself, a visually and net.art-historically literate statement that also serves to set the stage for the rest of the show.

This is clearly a politically motivated exhibition, with the theme of the exhibited art centred on a specific historical event (the Deepwater Horizon disaster). Oil spill and petrol station imagery dominates . The resulting art varies from cooly ironic asethetics (Ubermorgen), photo and video journalism (Guillermo Hermosilla Cruzat, S.Slavick & Andrew E.Johnson, Chris Dascher, Adrian Madrid), agitprop (Eric Benson, Geoffrey Michael Krawczyk, Alyce Santoro, Russ Ritell, Terri Garland, Patrick Mathieu), photography(Jessica Eik, Sabina Anton Cardenal), painting(Jessie Mann), collage(Ume Remembers), performance art(Graham Bell), interactive multimedia (Gavin Baily, Tom Corby, Jonathan Mackenzie, Chris Basmajian, Matusa Barros, Mark Cooley), augmented reality (Mark Skwarek and Joseph Hocking) and drawing (Cristine Osuna Migueles, Adrienne Klein, Jesus Andres, Sereal Designers) to video and audio art (Irad Lee, Luke Munn, Gene Gort, Tim Geers, Gratuitous Art Films, Alex George, Collette Broeders, Fred Adam and Veronica Perales, Virginia Gonzalez, Henry Gwiazda, Maria-Gracia Donoso, Jeremy Newman).

This is a lot to take in but the diversity of the work is a strength rather than a weakness, building a broad and visceral response to the Deepwater disaster. Verbal responses to the disaster from politicians seem unconvincingly nationalistic and corporate in comparison. It might seem hypocritical for artists to criticise the source of the energy that feeds us and allows us to make new media art. But we are trapped in that system, and we must be free to criticise it.

Politically inspired artworks have a difficult history, tending to be either bad politics or bad art. The art in Spill >> Forward is excellent, though. Some has a more direct message than others. Again the diversity of the exhibition plays a positive role here. The immediacy of the agitprop images doesn’t need art historical baggage to be effective, but that immediacy provides a social context for the more contemplative or abstract works. The more contemplative or abstract works don’t hammer home a simple political message but they provide an aesthetic context for the more direct images. They work very well together.

Some of the pieces in the show are clearly illustrations or recordings of work, some are electronic media that can be played on a computer, some are clearly designed to be experienced specifically through a computer system. If you removed the political theme of the show it would still be a visually (and audially) and conceptually rich cross-section of contemporary art. I was going to write “digital art” there but the show includes painting, drawing, performance, and other analogue or offline media recorded digitally for presentation online. The celestial jukebox is hungry.

If I had to pick out just a few pieces from the show I’d say that I was struck by the sounds of Luke Munn’s Deepwater Suite, by the visuals of Ubermorgen’s DEEPHORIZON, by the monochrome images and text of Terri Garland’s photography, by the video mash-up of Colette Broeders’ Breathe and by the critical camp of Graham Bell’s Radical Ecology. I think my favourite is Mark Skwarek and Joseph Hocking’s “The Leak in Your Home Town”, an iPhone app that uses the BP logo as an Augmented Reality marker to super-impose a 3D animation of the Deepwater leak over live video of your local BP petrol station. It is art that could only be made now, technologically, aesthetically and socially.

The aesthetic and conceptual competence of the artistic responses to the environmental and human crises of the oil spills in Spill >> Forward make the case for art still being a relevant and capable answer to society’s need to make sense of unfolding events. Art can still provide a much-needed space for reflection, and Spill >> Forward creates just such a space in a very contemporary way.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Article by Rosa Menkman

Based on an interview with the Critical Glitch Artware Category organizers and contenders of Blockparty and Notacon 2010: jonCates, James Connolly, Eric Oja Pellegrino, Jon.Satrom, Nick Briz, Jake Elliott, Mark Beasley, Tamas kemenczy and Melissa Barron.

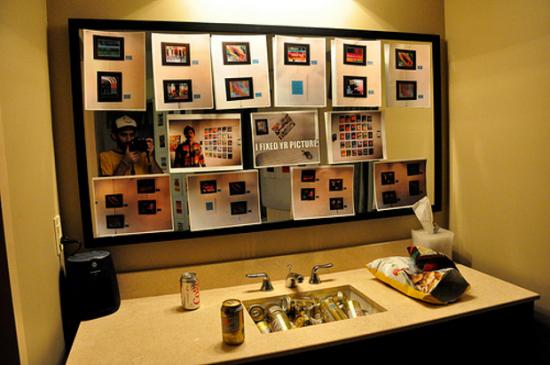

From April 15-18th, the Critical Glitch Artware Category (CGAC) celebrated its fourth edition within the Blockparty demoparty and this time also as part of the art and technology conference Notacon.

The program of the CGAC consisted of a screening curated by Nick Briz, performances by Jon Satrom, James Connolly & Eric Pellegrino, and DJ sets by the BAD NEW FUTURE CREW. There were also a couple of artist presentations and the official presentation of a selection of the (115!) winners within the Blockparty official prize ceremony.

The fact that CGAC was coupled with a demoscene event is somewhat extraordinary. It is true that both the demoscene and CGAC or ‘glitchscene(s)’ focus on pushing boundaries of hardware and software, but that said, I (as an occasional contender within both scenes) could not think about two more parallel, yet conflicting worlds. The demoscene could be described as a ‘polymere’ culture (solid, low entropic and unmixable), whereas CGAC is more like an highly entropic gas-culture, moving fast and chaotically changing from form to form. When the two come together, it is like a cultural representation of a chemical emulsion; due to their different configuration-entropy, they just won’t (easily) mix.

But all substances are affected (oxidized) by the hands of time; there is always (a minimal) consequence at the margin. And this was not the first time these two cultures were exposed to each other either; Criticalartware had been present at Blockparty since 2007. Moreover, a culture can of course not be as strictly delineated as a chemical compound; it was thus clear that this year the two were reacting to each other.

While over the last couple of years the demoscene has been described in books, articles and thesis’, this particular kind of ‘fringe provocation’ is not what these researchers seem to focus on; they (exceptions apart) concentrate on the exclusivity of the scene and its basic or specific characteristics. The ‘assembly’ of these two cultures during Blockparty could therefore not only serve as a very special testing moment, but also widen and (re)contextualize the scope of the normally independent researches of these cultures. So what happened when the compounds of the chemicals were ‘mixed’ and what new insights do we get from this challenging alliance (if there is such a thing)?

The demoscene is often described as a bounded, delimitated and relatively conservative culture. Its artifacts are dispersed within well-defined, rarely challenged categories (for the contenders, there is the ‘wild card’ category). Moreover, the scene is a meritocracy – while the contenders (that refer to themselves with handles or pseudonyms) within the scene have roles and work in groups, the elite is ‘chosen’ by its aptitude.

The demoscene also serves a very specific aesthetics, as enumerated by Antti Silvast and Markku Reunanen this week on Rhizome (synced music and visuals, scrolling texts, 3d objects reflections, shiny materials, effects that move towards the viewer – tunnels and zooming – overlays of images and text, photo realistic drawing and adoption of popular culture are the norm). In the same article Silvast and Reunanen declare that: ‘Interestingly, even though we’re talking about technologically proficient young people, the demosceners are not among the first adopters of new platforms, as illustrated by numerous heated diskmag and online discussions. At first there is usually strong opposition against new platforms. One of the most popular arguments is that better computers make it too easy for anybody to create audiovisually impressive productions. Despite the first reactions, the demoscene eventually follows the mainstream of computing and adopts its ways after a transitional period of years.'[1]

More about this can be read at Rhizome’s week long coverage of the demoscene. Silvast and Reunanen’s statement might be most interesting when we move along to see what happened during the meeting of the two scenes.

Co-founded by jonCates, Blithe Riley, Jon Satrom, Ben Syverson and Christian Ryan in 2002, Criticalartware is a radically inclusive group that started as a media art history research and development lab. Since 2002 the group has shifted and transitioned. Criticalartware’s formation was deeply influenced by the Radical Software platform (publications and projects). Since then it has been an open platform for critical thinking about the use of technology in various cultures. Criticalartware applies media art histories to current technologies via Dirty New Media or digitalPunk approaches. Through tactics of interleaving and hyper threading it permeates into cultural categories of Software Studies, Glitch Art, Noise and New Media Art.

During the first phase of Criticalartware (from 2002 – 2007), the group was a collaborative of artist-programmers/hackers. It also functioned as a media art histories research and development lab. In this form, Criticalartware had become an internationally recognized and reviewed project and platform.

When this phase ended in 2007, jonCates, Tamas Kemenczy and Jake Elliott were the remaining active members of Criticalartware. During this time, Elliott and Kemenczy wanted to take the project in a new direction; into the demoscene. This direction has ultimately defined the second phase of Criticalartware; an artware demo crew, making work for and appearing annually at the Blockparty event and Notacon conference in Cleveland.

2010 marked the next important transition for the Criticalartware crew, when it started using the phrase ‘Critical Glitch Artware’- Category. Criticalartware now not only organizes itself around the demoscene but also around the concept of the glitch. While a glitch (not to be confused with glitch art) appears as an accident or the result of misencoding between different actors, CA’s Glitch-art category exploits this possibility in an metaphorical way. Criticalartware is now foregrounding these glitch art works (with an emphasis on the procedural/software works) that have been on a ‘pivotal axis’ of the crew for a long time.

CGA, just like the demoscene, can be described as an open (plat)form for artistic activity/culture/way of life/counter culture/multimedia hacker culture and (unfortunately a bit of ) a gendered community. CA are about pointing out ideas or concepts within popular culture and incorporating (standardizing) these as machines or programs in a reflexive and critical self-aware manner.

CA can also be described as an investigating of standard structures and systems. They are often amongst early adopters of technology, in which they (politically) challenge and subvert categories, genres, interfaces and expectations. But the CGA – artists do not feel stuck in a particular technology, which makes it aesthetically, at least at first sight hard to pinpoint a common denominator.

There is not a real organization within this scene. The artists and theorists are scattered over the world, connected in fluid/loosely tied networks dispersed over many different platforms (Flickr, Vimeo, Yahoo groups, Youtube, NING, Blogger and Delicious).

Because of its bounded, intricate conservative qualities, the demoscene has been an easy target for outsiders to play ‘popular’ ironic pranks on, to misunderstand or misrepresent. A growing interest for the demoscene by outsiders has compelled jonCates and the Criticalartware crew to articulate their position towards the demoscene more extensively. In an interview with me, jonCates articulates Criticalartware’s points and contrasts these with problematic representations of the demoscene within two works by the BEIGE Collective (that in 2002 existed along side the Criticalartware crew in Chicago).

When the BEIGE collective went to the HOPE (Hackers on Planet Earth) Conference in 2002 they made a project called: TEMP IS #173083.844NUTS ON YOUR NECK or Hacker Fashion: A Photo Essay by Paul B.Davis + Cory Arcangel.

jonCates writes to me that ‘this problematic project characterizes or epitomizes a kind of artists as interlopers positionality that i + Criticalartware as a crew has always attempted to complicate. we do not want or understand ourselves as seeking out an ironic or sarcastically oppositional position in relation to the contexts that we choose to work in. we have not set out to ridicule the demoscene or otherwise make ridiculous our relations to the demoscene. in contrast, we set out to operate within a specific demoscene through multi-valiant forms of criticality, playfullness, enthusiasm, respect, interest, admiration, etc… this has also been in efforts to connect this specific demoscene to our experimental Noise & New Media Art scenes or what you Rosa referred to earlier as glitchscene…’

Another point of contention for jonCates is the Low Level All-Stars project by BEIGE (in this case, Cory Arcangel) + Radical Software Group (Alexander R. Galloway). this work is described as ‘Video Graffiti from the Commodore 64 Computer’ (2003) by Electronic Arts Intermix who sells/distributes this work as a video in the context of Video Art.

Low Level All-Stars has been shown at Deitch Projects in NYC in 2005 and circulated in the contemporary art world. jonCates writes to me saying the work seeks ‘to isolate + thereby establish cultural values for this ‘quasi-anthropological’ view of demos as found object + functioning as a tasteful ‘testament to a lost subculture.’ It is now being offered online as an educational purchase for $35 dollars.

However, as jonCates and Criticalartware work in the demoscene demonstrates, the demoscene subculture is not lost, nor over. jonCates moves on by writing that ‘the demoscene is a vibrant whirld wit a dynamic set of pasts + presents. this is another of which many (art) whirlds are possible. we seek to make those whirlds known to each others + ourselves out of respect, curiosity, investment, inclusiveness, criticality, playfullness, etc…’

The Criticalartware crew has been taking part in Blockparty since 2007, when it won the last place in a demo competition and was disqualified. One year later, in 2008, through a number of efforts (including Jake Elliott’s presentation Dirty New Media: Art, Activism and Computer Counter Cultures at HOPE, the Hackers on Planet Earth conference in NYC in 2008). CA was able to mobilize and manifest the concept of the Artware category at Blockparty, a category which Blockparty itself retroactively recognized CA for winning.

In the same year (2009) CA organized a talk at Blockparty in which they revealed the “secret source codes” of the tool they used to develop the winning artware of the year before.

By 2010 CA wanted to expand the concept of Artware within the demoscene, which lead to the development of the ‘Critical Glitch Artware Category’ event. Within the CGAC Compo there where 115 subcategory winners, which showed some kind of glitch-critique towards systematic categorization of Artware. Jason Scott (the organizer of Blockparty) personally invited CGAC to pick 3 winners and present their wares at the official Blockparty prize ceremony. Besides these three winners, CGACs efforts got extra credits when Jon Satrom’s Velocanim_RBW also won the Wild card category compo.

Therefore, not only did CA intentionally open up the Blockparty event to outsiders of the demoscene, it also provided a place for new media art and the glitchscene within the demoscene and got Blockparty to accept and invite the CA within their program. Thus, the outsiders (CA) moved towards the inside of the event, while the insiders got introduced to what happens outside of the demoscene (event), which led to conversations and insights into for instance bug collecting, curating and coding.

The Critical Glitch Artware Category has been accepted by, at least, the fringe of Blockparty 2010. Even though the category itself is not (yet) visible on the website, Satrom’s winning work Velocanim_RBW is. Moreover, CGAC was part of the official prize ceremony, streamed live on Ustream, the live Blockparty internet television stream. So how does CGAC redefine or reorganize the fringe between them and the demoscene and how does the demoscene redefine and reorganize the structure of CGAC?

For now, I think crystallized research into the aesthetics of the demoscene can also help describe the aesthetics within CGAC. Custom elements like rasters, grids, blocks, points, vectors, discoloration, fragmentation (or linearity), complexity and interlacing are all visually aesthetic results of formal file structures. However, the aesthetics of CGA do not limit themselves, nor should they be demarcated by just these formal characteristics of the exploited media technology.

Reading more about the demoscene aesthetics, I ran into a text written by Viznut, a theorist within the demoscene (who also wrote about ‘thinking outside of the box within the demoscene’). He separates two aesthetic practices within the scene: optimalism (an ‘oldschool’ attitude) which aims at pushing the boundaries in order to fit in ‘as much beauty as possible’ in as little code necessary, and reductivism (or ‘newschool’ attitude), which “idealizes the low complexity itself as a source of beauty.'[2]

He writes that “The reductivist approach does not lead to a similar pushing of boundaries as optimalism, and in many cases, strict boundaries aren’t even introduced. Regardless, a kind of pushing is possible — by exploring ever-simpler structures and their expressive power — but most reductivists don’t seem to be interested in this aspect”.

A slightly similar construction could be used for aesthetics within Glitch Art. Within the realm of glitch art we can separate works that (similar to optimalism) aim at pushing boundaries (not in terms of minimal quantity of code, but as a subversive, political way, or what I call Critical Media Aesthetics; aesthetics that criticize and bring the medium in a critical state) and minimalism (glitch works that just focus on the -low- complexity itself – that use supervisual aesthetics as a source of beauty). The latter approach seems to end in designed imperfections and the (popularized) use of glitch as a commodity or filter.[3]

Of course these two oppositions exist in reality on a more sliding scale. Debatebly and over simplified I would like to propose this scale as the Jodi – Mille Plateaux (old version) – Beflix – Alva Noto – Glitch Mob – Kanye West/Americas Next Top Model Credits continuum; A continuum that moves from procedural/conceptual glitch art following a critical media aesthetics to the aesthetics of designed or filter based imperfections.

This kind of continuum forces us to ask questions about the relationships between various formalisms, conceptual process-based approaches, dematerializations and materialist approaches, Software Studies, Glitch Studies and Criticalartware, that could also be of interest or help to future research into the demoscene. When I ask jonCates what other questions CGAC brings to the surface, he answers:

“when i asked Satrom to participate in the CRITICAL GLITCH ARTWARE CATEGORY event + explained the concept that Jake + i had developed to him he was immediately interested in talking about it as form of hacking a hacker conference, by creating a backdoor into the conference/demoscene/party/event. im also excited about this way of discussion the event + our reasonings + intentions, but i want to underscore that this effort is also undertaken out of respect for everyone involved, those from the demoscene, glitchscenes, hackers, computer enthusiasts, experimental New Media Artists, archivists, those who are working to preserve computer culture, Noise Artists + Musicians, etc… so while this may be a kind cultural hack/crack it is not done maliciously. we are playful in our approach (i.e. the pranksterism that Nick refers) but we are not merely court jesters in the kingdom of BLOCKPARTY. we have now, as of 2010, achieved complete integration into the event without ever asking for permission. perhaps that is digitalPunk. + mayhaps that is a reason for making so many categories +/or so many WINNERS! 🙂

…also, opening the category as we did (with a call for works [although under a very short deadline], an invitational in the form of spam-styled personal/New Media Art whirlds contacts + mass promotional email announcements of WINNERS! (in the style of the largest-scale international New Media Art festivals such as Ars Electronica, transmediale, etc…) opens a set of questions about inclusion.

…whois included? who self-selects? whois in glitchscenes? are Glitch Artists in the demoscene? etc… this opening also renders a view on a possible whirld, which was an important part of my intent in my selection of those who won the invitational aspect of the CRITICAL GLITCH ARTWARE CATEGORY. by drawing together (virtually, online + in person) these ppl, we render a whirld in which an international glitchscene exists, momentarily inside a demoscene, a specific timeplace + context.”

Lately the demoscene seems to get more and more attention from “outsiders”. Not only ‘pranksters’, artists and designers who are interested in an “old skool” aesthetic, but also researchers and developers that genuinely feel a connection or interest to a demoscene culture (I use ‘a’ because I think there still should be a debate about if there might be different demoscene cultures).

This development makes it possible to research a subculture normally described as ‘closed/bounded’ and to see where and how these different cultures are delineated. The tension between Blockparty/Notacon and Critical Glitch Artware Category is one that takes place on a fringe. They do not come together, but while it would be easy to just think that probably the CGAC sceners were just ignored (and maybe flamed) by the demosceners half of the time, some more interesting and important developments and insights also took place.

The CGAC-crew has over the years shown itself to be volatile, critical and unexpected, but it has also shown respect to the traditions of the demoscene and in doing so, earned a place within this culture (at least at Blockparty). This gave the CGAC-democrew not only the opportunity to put a foot in the backdoor of a normally closed system, but also to give some more insights into what they expose best: they confronted the contenders with their (self-imposed) structures and introduced them to (yet to be understood and accepted) new possibilities.

So what happens when a polymere is confronted with entropic gasses? I think the chemical compounds get the opportunity to measure the entropic elasticity of their dogmatic chains.

Also read:

Carlsson, Anders. Passionately fucking the scene: Skrju.

http://chipflip.wordpress.com/2010/05/20/passionately-fucking-the-scene-skrju/ Chipflip. May 20th, 2010.

Mark Napier’s Venus 2.0

Angela Ferraiolo

February 5, 2010

“Now that I’m done’ I find the artwork disturbing. It freaks me out. Maybe I’ll do landscapes for a while to detox.” — Mark Napier

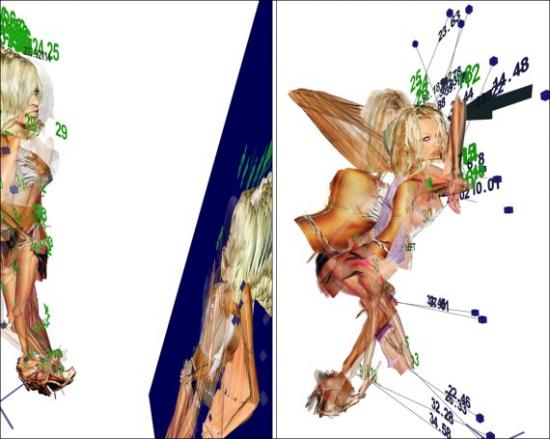

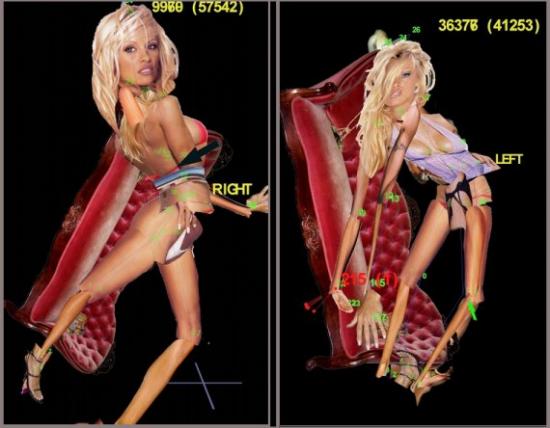

Artist Mark Napier, well-known for the net classics Shredder, Riot, and Digital Landfill, recently exhibited his latest work Venus 2.0 at the DAM Gallery in Berlin. A sort of portrait via data collection Venus 2.0 uses a software program to cross the web and collect various images of the American television star Pamela Anderson. These images are then broken up, sorted by body parts put back together and — as this inventory of fragments cycles onscreen, a leg, a leg another leg — the progressive offset of each rendering of Anderson’s head, arms, and torso makes her reconstructed figure twist, turn and jerk like a puppet. It’s odd looking. Even her creator is a little afraid of her:

“I have to say’ if I ever meet Pamela Anderson in real life I think I’ll completely freak out and run away. I don’t think I could have a conversation with the woman after this project … I started with a sympathetic view of the actual Pamela Anderson. She is part of the spectacle of sexuality in contemporary media. She’s caught in that ‘desiring machine’ as much as any other human’ probably even more so. She has surgically modified her body in order to have greater leverage in the media. Does this put her in control? I think not.”

Napier’s project doesn’t answer or intend to answer the question of who is in control either, but it plays with the possibilities. Although I wasn’t able to see the portrait at its exhibition. I did track down part of the series Pam Standing at a private location here in New York. Napier has also posted video excerpts of the work online. Unfortunately, these still images and clips are a bit too static to really do the piece justice. If you get to see the real thing and if you look for a while, you’ll see what I mean. Venus 2.0 is an amazing jigsaw puzzle, a deceptive surface of shifting layers – part painting and part search result.

The effect is translucent, lyrical, mathematic and creepy. When I implied that it must have taken an awful lot of precision and calculation to get something like this to come together, Napier insisted that focusing on the technology behind Venus 2.0, its algorithm, or even on the unique materiality of networked art in general, is a way of missing the point. The way he relates to Venus 2.0 is through the painter’s hand. What counts is not the data feed, but who were are, what we want and how we behave:

“The artwork is a riff on sexuality as an elaborate hoax played by a precocious molecule that builds insanely complex sculptures out of protein, aka, meat puppets or more simply, ‘us’. These animate shells follow a script that’s written and refined over the past half billion years. And that script is in a nutshell: 1) survive 2) reproduce 3) goto #1. So sexual attraction is the carrot to DNA’s stick. Attraction is part of the machine. In art history this appears as the tradition of Venus. And more recently: Duchamp’s ‘Bride’. Magritte’s ‘Assasin’. Warhol’s ‘Marilyn’. The focus of digital art is still the human being. Don’t be distracted by the gadgets.”

Hi-tech or not, new media artists are by now well-practiced in the technique of unraveling a familiar image to expose an occluded, yet equally valid identity. In Distorted Barbie, Napier relied on a repeated process of digital degradation to blur both the literal and conceptual fiction of the Mattel franchise. Another early project stolen, took the female body apart, presenting attraction as database. Years later these kind of approaches, pixel manipulations and indexing without comment, as well as parsing and remixing have become a sort of standard operating procedure in new media. So much so that as technique becomes more well-known and more accessible, it can be hard to tell one work from another or one artist from the next. With this in mind’ it seems important to note that in the case of Venus 2.0 it is not so much a choice of subject or an organizational scheme that guarantees the final effect, but the manner in which Napier investigates the image and the ways in which Napier illustrates and manipulates both the visual elements of portraiture and his relationship to the figure involved.

Napier builds and destructs, assembles and tears apart, but in doing so tries his best to keep us focused on these activities as processes. At times Pam’s contortions are allowed to expose the wireframe which allegedly guides her construction and at certain key points on the interface, there is also a steady stream of vector coordinates to embody the idea of data. But Napier makes less of technology than another artist might by effacing what some would tend to elaborate on, in order to draw our attention elsewhere – usually towards evolution, gradation and the ways in which images evolve, and by extension the ideas that inspire those images which reflect how unstable elements are, even treacherous:

“I work at probabilities: what is the likelihood that the figure will be totally opaque? How often does it get murky and undefined? How often should I let that happen and for how long? How often does the figure jump? How long till the figure lands and stands up again? How much time is spent in chaotic motion and how much in stillness? How often does something completely messy happen? Like the figure gets tangled up in a ball that has no structure. I don’t know how the piece will play out each minute, but I know what kind of situations will arise in the piece. I can plan those likelihood, and then let the piece play and see what it does.”

So, like the woman who inspired her. Pam Standing is beautiful, but more unsettling. What makes Pamela Anderson the most frequently mentioned woman on the Internet? Why do we mention her? What is it we want when we give our gaze to celebrity? What has celebrity done to attract us? Whatever your answers, what Napier privileges in his response is not a fixed portrait of a star, but a cloud of iteration that produces its own image and reproduces that image, jangled, confused and full of surprises. A portrait whose finest moments are accidental and whose design is an accumulation of fragments that tense and dissolve, floating like clouds one instant and then sinking like lead the next. This is where the imagination takes a step forward and Napier the artist or Napier the geek becomes Napier the puppetmaster, a networked Dr. Coppelious:

“My favorite moment with the PAM series was when I finally got all the math to work so that the body part images displayed correctly and the correct side of the body showed at the right time and the stick figure suddenly started to look like a ‘real’ puppet that was starting to come alive in the golem-esque way that I thought it could when I was sketching out the idea. I had that Dr. Frankenstein moment: ‘She’s aliiiiiiiiiive!!!!!!!!!!!!!’ which was really the point all along, to create this virtual golem that is clearly not alive at all and yet teases us all with this false appearance of life. Venus 2.0.”

Until the layers of arms, legs, breasts and hips collapse in on themselves and Pam is back where she started, a manipulated beauty unable to escape presentation as a collaged monstrosity.

Note: Mark Napier has been creating network art since 1995. One of the earliest artists to deal thematically and formally with the Internet, Napier has been commissioned to create net art by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His work has appeared at the Centre Pompidou in Paris’ P.S.1 New York’ the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis’ Ars Electronica in Linz’ The Kitchen’ Kunstlerhaus Vienna’ ZKM Karlsruhe’ Transmediale’ iMAL Brussels’ Eyebeam’ the Princeton Art Museum’ la Villette’ Paris’ and at the DAM Gallery in Berlin.

This article is co-published by Furtherfield and The Hyperliterature Exchange.

Millie Niss, the writer and new media artist, died of swine flu with complications at 5 a.m. on 29th November 2009. Her mother and longtime collaborator, Martha Deed, was with her then. She had been in hospital for four weeks, mostly in intensive care, after picking up the virus, which quickly became serious in her case, probably because she already had respiratory difficulties due to a rare condition known as Behcet’s Disease. She was 36 years old.

The news would have been sad to hear about anyone, but it was especially sad in Millie’s case because she was one of the people in the new media community with whom I felt particularly close. I met her at the trAce “Incubation” conference in Nottingham in 2004. When I first arrived at the conference, I was directed to the part of the room where Michael Szpakowski was because he and I had already struck up an e-mail friendship, and he’d left a message for me at the door. I found him talking to Millie. Michael was only there for that first evening because he had to go and see his father, but Millie was there for the rest of the conference, and I sat next to her at many events. She was dark-haired, overweight and funny: very easy to talk to. Later in the conference, she gave a presentation about how to attach behaviours to objects in Flash, which I attended along with Jim Andrews and others. She kept saying beforehand that she was feeling pretty nervous about it, but she seemed very natural and nerveless when it came to the event. In the beginning, she asked for suggestions from the audience – I think for an initial idea on which to base her Flash piece – and at first, nobody said anything. She suddenly became acerbic – “Oh come on – don’t make me pick on someone like you were a bunch of school kids!” Immediately you could see her as a teacher and imagine how she would have controlled a classroom. I suggested spiders, which set the ball rolling, and from that point onwards, everything went very rapidly. She quickly and expertly demonstrated how to set up a drawing of a spider as a symbol, and attach a behaviour to it so that when the mouse pointed to it, a sound file played. Another thing I remember was that she was very critical of certain aspects of Flash – how you had to import things into your library and then drag them from the library to the stage before you could do anything with them. You could feel her personality’s force, her opinions’ sharpness, and her sense of humour and fun.

From that time onwards, she and I regularly exchanged e-mails. She knew that I worked in the National Health Service, and because she was very much in the mill of health care herself, we had some lengthy correspondence about how the UK system worked, compared with how things worked in the USA. She also sent me two glass unicorns through the post – occasionally, she would run little competitions on her “Sporkworld” website and offer glass unicorns to participants as prizes. The first of these unicorns went to my daughter Rachel, and the second is still sitting on my study window-ledge in a white cardboard box. He used to stand out on his own four feet, but unfortunately, he had an accident with the curtain, and one of his legs got knocked off. I stuck it back on with Superglue, but it fell off again. Millie knew all about this, and I sent her a photograph of the unicorn on my window-ledge – I think I even sent her a second photograph, showing how he looked after his accident and temporary repair. She was always very interested in Rachel and liked to hear my stories about her. Perhaps they reminded her of her childhood, or perhaps she just liked kids.

One thing which came across from Millie’s correspondence, as well as from her work and her occasional online commentaries, was her sense of perspective on new media art. She was grateful to it because it provided an outlet for her creativity which she had never managed to find through traditional print; but all the same, she remained aware that it was a small and specialised field and that a good deal of new media work might seem incomprehensible to “ordinary” people. Her comments about other new media artists reflected this grounded attitude. She preferred work which didn’t reach for the hi-tech solution that a lo-tech one would do – work, in other words, which didn’t employ technology for its own sake, and where the form was dictated by content rather than the other way round. Likewise, she wasn’t particularly bothered whether her output complied with the dictates of new media theory – whether it was interactive, non-linear, coded or networked. The pieces on her website exhibit a cheerful mixture of genres and media: Flash, video, poetry, prose, photography, sound files and plain old HTML rub shoulders in much the same way that political commentary, literary criticism, observations of places and people, food appreciation, nature notes, raucous humour and occasional obscenity rub shoulders in her blog. The groundedness of her art, and her sense of responsibility towards her audience, is demonstrated by the way in which she habitually presented videos on her site in different sizes and resolutions – for example, “Warhol’s Campbell’s Brodo” is available 8.85mb, 6.23 MB and 2.43 MB – so that people with slower connections could sacrifice a bit of quality to save a long wait if they so desired. Similarly, her introduction to “Warhol’s Campbell’s Brodo” explains that “brodo is the Italian word for soup and the restaurant’s name”. Without talking down to her audience or limiting what she wanted to say, she was always at pains to be as clear and user-friendly as she could – and this insistence on clarity and user-friendliness, her desire to reach out to an audience of “ordinary” people whenever possible, was one of the things which made her voice such a distinctive and refreshing one in the new media world.

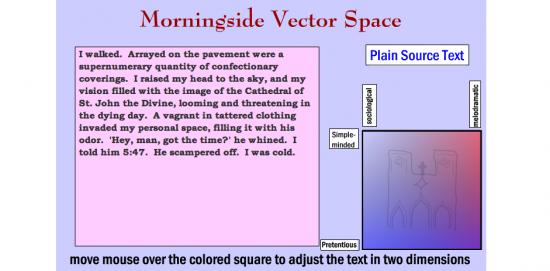

However, this is not to say that she was any Luddite or uninterested in the theory of any description. One of her best-known pieces of work – a collection of six pieces – is the Oulipoems, reproduced in Volume One of the Electronic Literature Collection in 2006. As Millie explains in her introduction, “Oulipoems is a series of six interactive poetry Flash works… loosely based on the Oulipo movement in French literature, which focused on texts based on constraints… and also on mixtures of literature and mathematics.” One of the Oulipoems is “Morningside Vector Space”, which rewrites a description of a simple incident in various ways, depending on how we move the mouse cursor over a coloured square. The source text reads:

Yesterday, I was walking on Amsterdam Avenue. There were cracks in the sidewalk. I looked up and saw the tall and unfinished Cathedral of St. John the Divine. A man approached me. ‘Excuse me, do you have the time,’ he said. I told him at 5:47. He walked (sic) away. It was windy. The coloured square is marked to indicate the inflexions this text will be given if we hover over different areas – from “Simple-minded” to “Pretentious” on the x-axis and from “Sociological” to “Melodramatic” on the y-axis. If we point to the “Simple-minded” corner, we get this:

I walked. On the sidewalk. By the big church. There was a man. He wanted the time. I gave him my watch. He left. I was cold.

The intersection of “Pretentious” with “Melodramatic” yields this:

A vagrant in tattered clothing invaded my personal space, filling it with his odor. ‘Hey, man, got the time?’ he whined…

The intersection of “Pretentious” with “Sociological” produces:

The sidewalk, unmaintained by the municipality, contained evidence of substance abuse…

– and so forth.

A number of observations come to mind about this piece. First of all, although it isn’t tremendously technically sophisticated, it does reveal a very competent grasp of Flash and object-oriented coding. This grasp is also displayed in many of Millie’s other pieces. Secondly, it demonstrates the “mixture of literature and mathematics” to which Millie refers in her Introduction to the Oulipoems – the idea that different styles of writing can be mapped onto a graph and summoned by pointing at different vectors – and in doing so, it demonstrates a willingness to experiment with text, and an openness to the idea that text in digital literature may sometimes be manipulable by the audience, rather than fixed into a single unquestionable form by the author. Thirdly, “Morningside Vector Space” is funny and accessible. The labels with which Millie marks out her vectored space are humorous, and the texts with which she illustrates these different writing styles are exaggerated for comic effect. At the same time, there is an undercurrent of social observation, with a suggestion of political edge: “I was observing a mixed-income neighborhood on the borders of a low socioeconomic enclave… Lacking funds for a watch, he had to rely on others in the community to be on time for his appointment with the social services…”

Lastly, perhaps least obvious is a powerful sense of place. The piece’s title refers to Morningside Heights, an area of Manhattan in New York. The texts allude to Amsterdam Avenue, a street in Morningside, and the Cathedral of St John the Divine, which stands there. St John the Divine is also known as St John the Unfinished because although it was begun in 1892, it remains incomplete to this day – hence the description of the cathedral as “tall and unfinished”. The coloured vector space in Millie’s piece contains another reference to the cathedral, in the shape of a wobbly but recognisable line drawing of its facade. This sense of place is an important aspect of Millie’s output – not only in videos about places such as “Jewel of the Erie Canal” or “A Hecatomb in Cheektowaga” but also in new media works such as “The Talking Escalator at Penn Station”and “Unscenic Postcards” – and like her interest in politics, it demonstrates her commitment to the “real” world, as well as her talent for observation and comment.

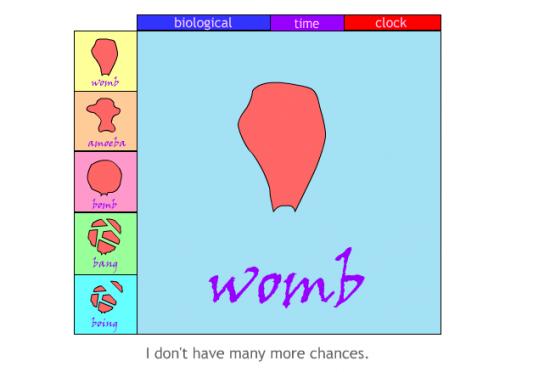

Another of Millie’s Flash pieces, and one of her most personal artworks, is “Biological Time Clock”. In a central pane, the words “womb”, “amoeba”, “bomb”, “bang”, and “boing” appear, accompanied firstly by Millie’s voice intoning the same words, and secondly by drawings of a womb, an amoeba, a womb inflated to the point of bursting, a womb breaking into pieces, and another slightly different drawing of a womb in bits. Underneath this pane appears a randomised sequence of phrases, arguing both for and against getting pregnant and giving birth: “It’s not for me”, “I’d be nurturing”, “I’m more than a womb”, “I’m not together enough”, “maybe I should do it while I can”, and so forth. There are also buttons that allow you to add extra sound effects, such as Millie saying “tick-tock” or chanting “biological”.

There are feminist aspects to the piece – one of the anti-pregnancy phrases is “I don’t want to be a breeding cow”, and another is “I’m more than a womb” – mixed with what seem to be more autobiographical notes, such as “why am I alone?” and “I don’t want to lose my creativity”. However, a question that seems to go to the heart of the piece is what is the word “boing” doing in there? The drawing which accompanies this word is enigmatic. Still, it may be meant to suggest that the womb, which broke apart at “bomb”, is now somehow bouncing back together again – and by implication, that no matter how many times the author talks herself out of childbirth, her consciousness of her womb keeps coming back to bother her afresh. But the word “boing” serves another purpose by introducing into the piece the quirky, unpretentious, comical note essential to Millie’s art. If the word sequence at the heart of the poem were simply “womb, amoeba, bomb, bang,” then both the message and the tone would seem much starker. With “boing” on board, there is a playful and funny element to the piece, a release from serious description into exaggeration, which seems to suggest that Millie herself isn’t taking it completely seriously, and we don’t have to take it completely seriously either.

In some ways, this insistence on the quirky and the wacky might be considered a weakness or a limitation in Millie’s art, flinching away from completely direct and honest engagement with her subject matter, symptomatic of a tendency to let both herself and her audience off the hook, especially if her subject-matter happens to be personal. But it should be borne in mind that Millie had more personal subject matter to deal with than most of us, and her insistence on humour was an essential part of her strategy for dealing with it. One of the anti-pregnancy arguments on “Biological Time Clock” is “I’m not well…” and it is impossible to write about Millie’s art without taking her mental and physical ill health into account, if only because so much of her art deals with it. For many years she was considered – and considered herself – to be mentally ill with Bipolar Disorder. Millie’s experiences of mental illness and the health and social care professionals with whom it brought her in contact are memorialised in “The Adventures of Spork, the Schizophrenic Skua”. As described on Millie’s site:

Millie Niss created Spork… to be a sympathetic and intelligent character who was also an indigent client of the mental health system. The cartoons began to express frustrations about how mentally ill people and welfare recipients are treated, but later on, other issues and pure silliness were added to the Spork series.

Eventually, after years of treatment for mental illness, Millie was diagnosed with Behcet’s disease, a severe disorder of the immune system which can cause depression along with ulcers, skin lesions, stomach problems and inflammation of the lungs. Before this diagnosis, however, she suffered attacks of dangerously acute depression, and one part of her website is devoted to suicide (http://www.sporkworld.org/suicide). The way in which she tackles this subject makes it clear how her sense of humour, far from demonstrating an unwillingness to confront her inner demons, was really evidence of her mental toughness and self-discipline in dealing with them – a refusal to give in to self-pity:

I was often, very often ready to kill myself, but I hate guns and wouldn’t want to use one. And lying on a gun license application was out of the question: I would not sign my name to a paper which said I was not intending to kill myself or was not mentally ill… Hanging was reputed to be painless and so we thought getting sentenced to death was the perfect out: that way you could have the benefit of dying without the guilt of doing it to yourself. It was unfortunate that you had to do something awful to get sentenced to death, though… A big question was the suicide note. Should you leave one or not, and if so what should you say in it? The argument for not leaving a note was a strong one: someone might find the note and stop you from doing it… The desire to write a suicide note that was a literary masterpiece kept me alive at times. I couldn’t kill myself until I thought of something good enough.

In these passages, Millie combines a sharp, satirical, almost gleeful insight into the ironies and self-contradictions of the suicidal mindset with an understated – but nevertheless essential and genuinely tough – conviction of her individuality and status as an artist. As she insists in “Biological Time Clock”: “I have a brain”, “I’m more than a womb”, and “I don’t want to lose my creativity”. In “Suicide”, the idea that she doesn’t want to kill herself until she can devise a sufficiently well-written suicide note is a good joke at her own expense. Still, it also points to something deeper: her writing is her way of dealing with depression and her reason for not succumbing. It gives her a sense of self-worth, and the discipline of art allows her to detach herself from her feelings and sublimate them, thereby gaining some form of control over them.

In an article entitled “Suicide, Art, and Humor”, which she published on Michael Szpakowski’s website “, Some Dancers and Musicians”, Millie wrote that “The artist has a duty, some might say, to produce art. But with that comes the more fundamental duty to stay alive.” This is a typically grounded remark: the artist’s duty to life is “more fundamental” than her duty to art. Referring to her own “Suicide” piece, she goes on: “I was at least trying to be funny… Art is a force that tends towards life… While you are writing a despairing poem, you are, in the act of writing, temporarily suspended from the act of despairing.” The effort to be funny and thereby entertain an audience, art as an affirmation of life, and art/humour as a defence against despair – all of these ideas were essential to Millie’s work.

The same values are apparent on the Sporkworld Microblog, which Millie shared with her mother, Martha Deed. They are present even in the very last days of her final illness. Here is an entry from 16th November: “We like to keep a chipper tone here, and we do not intend this to be a place to list complaints. We also insist that any personal events must be… transformed from raw anecdote into something with literary intent.” Martha actually wrote this, but Millie approved it, and it reflects a shared philosophy that runs right through the site’s contents. “Raw anecdote” is inadmissible, not only because it may lack the “chipper tone” that the Microblog seeks to maintain, but because it also lacks the discipline and detachment of real art. The word “raw” suggests something of the harshness of unfiltered experience. The artist’s job is not to pass on this harshness to the audience direct and unmediated, but to control it through an effort of will, to fit it into a composition, to comment on it, reason about it, make jokes about it and turn it into an element in discourse; and thus to humanise it.

After Millie’s death, Martha published a poem on the Microblog entitled “Travelling with H1N1”, which contains the following lines:

even if it is difficult to be funny

while intubated, you will fight and fight and fight…

you will be sending email on your way to the fluoroscope

with subject lines like

I never thought I would write email while intubated”…

The sense of humour, the refusal to give in, and the determination to fight back against her difficulties by finding something to say about them were all there until the very end. Martha relates that in the intensive care Unit (ICU), although she couldn’t speak because she was on a ventilator, she kept her lines of communication open by writing things down. She struck up a friendship with a nurse supervisor, Tom, who “was astonished at her ability to tolerate the ventilator and keep up a running conversation in her notebooks… He continued to visit her in the ICU and received her candid evaluations of her care there – both good and bad – and he found her to be very funny and brave.”

Mentioning the Sporkworld Microblog, and the fact that it was shared with Martha Deed, brings us to Millie’s frequent and long-term collaborations with her mother. Millie is known as “Spork Major” on the Microblog, while Martha is “Spork Minor”. Apart from the blog, they collaborated on many other works – Martha co-wrote the “Oulipoems” texts, for example, and “Jewel of the Erie Canal” is credited to them both. But one of the largest, most ambitious and most formally developed of their collaborations is News from Erewhon, a series of parallel surreal fictions created by the process of “guided free association”.

News from Erewhon is by no means a perfect work of art. Firstly, the title makes a rather distracting reference to Samuel Butler’s satirical, pseudo-Utopian novel “Erewhon”, which doesn’t really seem to have much to do with the rest of the book. Secondly, each chapter is accompanied by a number of images which zoom up in front of the words and then quickly fade away to allow us to read on. The Introduction argues that these add “another level” to work and that the pictures “appear only briefly to affect the viewer in an almost subliminal manner”. In fact, their main effect is to make you lose your place. Luckily, Millie provides a button which allows us to switch the images off.

Nevertheless, the texts themselves are fascinating. They were written in an almost Oulipo-like manner. Several words were picked randomly from chosen books; then, using these words as “seeds” and incorporating them into their writing as they went along, both Millie and Martha produced a series of eight “miniature fictions, situated halfway between poetry and prose”. As the Introduction says, these fictions suggest “a bizarre alternate universe, whose characters and settings evoke themes such as war and peace, the workplace, and religion. These themes… weave in and out of the texts like strands in a braid. The two authors can also be seen as separate, interacting strands.” The image of strands in a braid suggests both the closeness with which Martha and Millie were able to work together and the fact that they always retained their distinct identities and styles, and News from Erewhon is a good demonstration of this. Millie’s sections are generally longer than Martha’s and more narrative in style, whereas Martha’s tend to be more surreal and poetic. Both, however, display a constant flow of inventive wit. One of the funniest of the lot is Millie’s fourth:

The mice lived in a cream-colored bungalow under Mrs Johnson’s sink. Or so at least it seemed to them. Others less culturally attuned might have seen only some half-eaten Triscuits and the remains of a sesame bagel… “God save all the creatures who crawl under the moon, and all of their offspring,” murmured Chuck in a non-denominational invocation of the Divine. He would feel differently in the morning when he blistered his toe in the empty mousetrap from which the clever mice had stolen the cheese. “God Fuck!” he would swear into the mirror, cursing his fate as he brushed the All Bran from his teeth.

Seed-words for the passage are shown in bold. Here is an extract from Martha’s equivalent passage:

A cream-colored bungalow? How could you? It will curdle in the sun, and this is July, she said… Your invocation of natural disasters has blistered the mirror of my mind, he moaned.

Both writers, it will be noted, start by cheating: instead of introducing the “cream-colored bungalow” into their stories in a literal-minded way, they bring it in obliquely. Martha imagines a bungalow, not the colour of cream, but actually painted with cream on the outside – hence the objection that “it will curdle in the sun” – while in Millie’s story, the bungalow only exists at all in the collective imagination of a family of mice. Martha sticks more closely to an underlying structure suggested by the seed words, producing a more densely written text and poetic texture. This is particularly evident in the alliteration – “colored”, “could”, and “curdle” or “mirror”, “mind”, and “moaned”; but also in the lilting rhythm – “Your invocation of natural disasters has blistered the mirror of my mind, he moaned”. Millie, on the other hand, shows something of the novelist’s delight in incidental detail – “Triscuits”, “sesame bagel”, “under Mrs Johnson’s sink”, and “he brushed the All Bran from his teeth”. Her passage seems to take a serious turn with the phrase “God save all the creatures who crawl under the moon” – simultaneously poetic, literary and religious – yet this moment of gravity is almost immediately reversed by an explosion of comical blasphemy – “God Fuck!”

It would be too simplistic to suggest that Martha was always the more focused and disciplined partner in collaborative work. It should be remembered that Millie was the techno-savvy one, and therefore the design and construction of the Sporkworld site, the Microblog and News from Erewhon were all carried out by her. Her work in this area is always individualistic rather than textbook. Still, at the same time, it exhibits both a powerful emphasis on user-friendly functionality and a considerable visual flair. She may have presented herself as the mercurial, comical, slightly wacky half of the partnership, but there was always a sharpness, toughness, self-discipline and a determination to succeed just under the surface.

On the other hand, Millie’s work undoubtedly has an impulsive element, and in the collaborations, this makes a compelling contrast with Martha’s more studied approach. “God Fuck!” is one example; another is “Voting”, a video made in November 2008 showing Millie’s difficulties, as a disabled individual, in trying to deal with her postal vote form. Her ballot paper combines a list of presidential, senatorial, and Congress options and several constitutional issues specific to North Tonawanda, the town in which Millie and Martha live. As a result, it’s a huge sheet about the size of a tablecloth, with as many creases as an Ordnance Survey map, and just as difficult to flatten or re-fold. Step by step, Martha takes Millie through the different options on offer, with Millie keeping up a gunfire of questions and acerbic commentary, interspersed by short periods of silence during which she gasps for breath. Both Martha and Millie are represented on-screen mainly by their hands – first Martha’s, as she manipulates the ballot paper and fills it out in accordance with Millie’s instructions; then Millie’s, towards the end of the process, as she signs the outside of the envelope to authorise her vote. Apart from this, they are represented by their voices: Martha’s calm and methodical, Millie’s staccato and satirical, but both become increasingly impatient as the difficulties of dealing with the ballot paper become increasingly apparent. Ultimately, Martha can’t get it folded to fit the official envelope. Then Millie has to rehearse her signature because her hands are so afflicted with arthritis that she struggles to hold a pen. Then the envelope is difficult to sign because it’s so fat and unshapely with the ballot paper inside it. Then it turns out that the envelope will have to be taken to the Post Office and weighed because it isn’t pre-franked or freepost; at which point –

MILLIE: Okay, so we’re gonna have to pay postage on top of this… and it has to be weighed because it’s so fucking heavy!

(Slightly shocked pause.)

MARTHA (elaborately self-restrained): Did you mean to put the word “effing” in?

MILLIE (immediately): I did! I absolutely did! I mean, it’s a matter of free speech. The Supreme Court would have upheld my right to say fucking on my own blog. There have been efforts to make it impossible to say that.

MARTHA (holding up the envelope, with a noticeable change of subject): Okay, I think we actually have it done.