Feature image: Winchester School of Art Exhibition of Data Asymmetries. Image Credit: Olcay Öztürk

Burak Arikan is one of Turkey’s leading media artists, a figure who straddles the lines between technologist and practitioner. He explores relations between data and transactions, the regimes of datafication and identification as control, and maps relations of power and invisible infrastructures with network mapping tools. According to new media theorist Jussi Parikka, Burak’s pieces “raise questions of the predictability of ordinary human behavior with MyPocket(2008); reveal insights into the infrastructure of megacities like Istanbul as a network of mosques, republican monuments and shopping malls (Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism, 2012); remap and organise recurring patterns in the official tourism commercials of governments with Monovacation (2012); explore the growth of networks via visual and kinetic abstraction with Tense (2007-2012); and showcase collective production of network maps from the Graph Commons platform.”

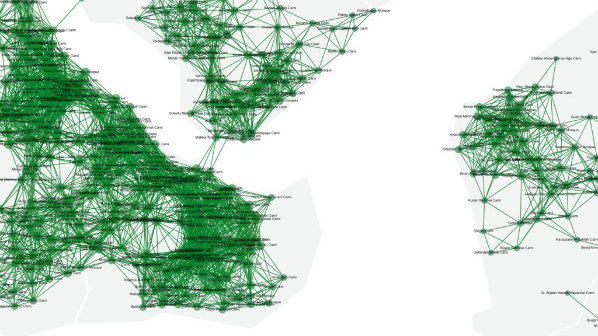

Burak’s creation of the Graph Commons, an online network mapping tool, is an open platform for the creation of networks that encourages its users to explore the functional limits of network architectures as a mechanism for storytelling, data visualization, and modelling our contemporary moment, from graphing financial microtransactions to mapping superstructures splayed across a continent.

Burak Arikan’s most recent body of work, Data Asymmetry, was hosted at the Winchester School of Art from November 10-24, 2016. His network mapping tool, Graph Commons, is viewable here.

In the first of this two part interview series, Carleigh Morgan speaks to Burak Arikan about his practice. In the second part of the series Morgan interviews Jussi Parikka about Arikan’s work and the way data and networks condition and build the way we view and interact within the world.

CM: The aim of the Graph Commons is to “empower people and projects through using network mapping, and collectively experiment with mapping as an ongoing practice.” But every visualising methodology has its hermeneutical blindspots and invisible shortcomings.

With those boundary constraints and affordances in mind: What are networks in art, and how are they are extensions of or departures from the networks that they attempt to depict?

BA: I use network as a map vs network as an event separately in my work.

Network as a map is simply using dots and lines to represent observed or measured relationships in order to explore the structures of rather complex systems in life. For example, I am interested in revealing the institutionalization without walls in the world of art, so I look at relationships of artists exhibiting together with other artists, art institutions related by the artists they show, influence of collector-artist relations etc. Such network mapping reveals central actors, indirect connections, organic clusters, structural holes, bridging actors, outliers etc. Network mapping provides a view of such qualities about that particular art world that you wouldn’t see otherwise.

A network map is both a visual and a mathematical language, that you can visually follow dots and lines with your eyes, as well as apply calculations on this data diagram. When you simply record and measure activities as data points, then you can link them to generate more insight and value from the linked whole than the sum of its parts. This is typical data linking method is commonly employed in security, marketing, finance, and social media industries by governments and corporations. One position I have in my art is to use such data mapping and analysis capacity on power relationships, mapping the ones who are mapping us. No need to say, my work is not necessarily about the internet of art things, but I’ve been interested in revealing the relations at scale in variety of fields ranging from juridical systems to cinematic languages.

Network as an event is a living substrate, it is people hanging out together, machines transmitting data packages, neurons firing signals, online platforms for social networking, physical ecosystems of humans and animals where widespread infectious disease can occur. These are physical, digital, hybrid living and multilayered systems maintained by diverse interactions between independent agents, where their small interactions governed by certain protocols together constitute an ever changing larger whole. Building a living network, or network as an event is another line of effort I’ve been pursuing in my work. For example, in 2007 I’ve built Meta-Markets, an experimental online stock market for trading social media profiles, where users did IPO (Initial Public Offering) their profiles and traded with others, with a goal to evaluate the value of a social media profile, the information you cannot get from the service provider company. It ran for 2 years and a community of members formed a dynamic trade network among a couple of thousand social media profiles.

CM: What types of agencies do network maps engender their makers with, and what kinds of constraints to they bring to bear on their creators? As an artist who works with the form of networks, have you witnessed a formal re-alignment of your thinking to reflect these structures? Through ongoing interrogations with and construction of networks as an aesthetic model, would you consider yourself more alert to the networks that condition our contemporary moment?

BA: As with any research, network maps are subjective too. Because by just measuring a reality you claim a subjective position. Thus, data points are always generated, rather than collected. Furthermore, network diagrams are usually totalizing and contemplative. As McKenzie Wark writes criticizing Frederic Jameson’s cognitive mapping: network maps freeze into a contemplative totality that prescribes an ideal form of action that never comes.

My network mapping work starts with raising new questions on critical relations that scale. Then I conduct research to generate data about a “particular world”, which enables many stories, interpretations, and use cases.

As a response to the lack of the “dialectical” in the frozen totality of static diagrams, I started using algorithmic interfaces in my installations. Such interactive network maps let you touch and change the positions of the dots on a map, yet browse the names without losing their relationality to each other as the software simulation continuously organizes the network layout. This way, normally invisible relations not just become visible, but also touchable, which enables us to effectively explore the chain of influences and relationality at scale. Touching the nodes also displays information cards, where you can get richer information about individual data points. By using an algorithmic interface you navigate back and forth between an abstract large picture and concrete juicy details of a complex issue. I think such encounters help the viewer to effectively interrogate the particular issue at hand and develop better insight. This aesthetic and pedagogical experience of interactive cartography is very different from a static diagram, that still lacks criticism.

CM: There’s a resounding common thread in your work [the mapping of the urban infrastructure of Istanbul in terms of its mosques, malls and national monuments in Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism demonstrates this clearly] that seeks to articulate the imbricated matrices of politics, art, and the practices of everyday life that are often not apprehensible to the individual occupied with the attention-consuming projects of being and living.

How does your work position the actor within the network, and what kinds of political commitments do you see expressed from your position as the authoritative designer/person who captures these networks in artistic form?

BA: Since a network map provides a world rather than a story and is thus a nonlinear medium, there is no flow of introduction, development, and finalization, neither a single story. So you start exploring a network map from a “you are here” point, a familiar name or an interesting image, which may be different for every other viewer. Then you do an unplanned journey through a topology of connected information points, navigate from one connection to another. You experience a traversal, a situationist dérive on a data network.

In my workshops and lectures I tell people not to use network mapping against themselves. Network mapping is a powerful tool, it makes structures transparent. Keep the maps about yourself to yourself. Turn it around and map the ones who map you.

In fact, when you click on a follow button, swipe a metrocard, or use your credit card your data is being captured and mapped by data-driven oligarchies. Obviously, this is not just a concern of privacy violation, in this day and age, data capturing is about ownership and control, thus capital and power.

CM: MyPocket generates data from bank transactions, Monovacation from tourism commercials, Islam Republic Neoliberalism organises data collected about the urban infrastructure, Tense Series generates semi-random numbers and uses it as data.

How does your work foreground how data–as algorithmic material that exists at the level of computation, below the thresholds of human apprehension– conditions and structures the world we live in?

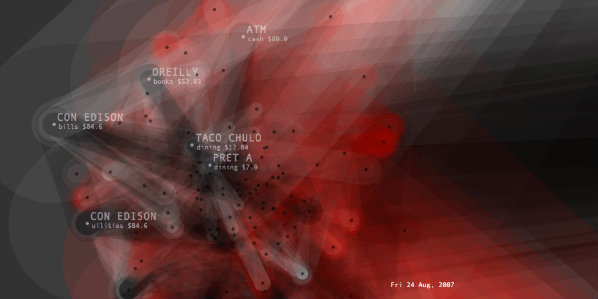

BA: Data about us, metadata, make our everyday behaviour more predictable. No one wants to live such a boring predictable life. In MyPocket (2008), by predicting and publishing what I will buy every other day, I demonstrated how easy it is to algorithmically predict our mundane behavior. With this work, in a way I sacrificed myself by making my data no more exclusive to a bank but available to anyone else, so that you can start thinking what corporations can predict about yourself and what it might mean to you.

By turning data around, we can reveal systematic yet invisible power structures. For example in 2012, I mapped a network of Istanbul’s 3000 mosques based on their overlapping call to prayer sounds. Most people living in Istanbul are born into this and take it for granted. However, the mosque network constitutes a subtle power structure, which became quite apparent to many as the government used this network to make calls to city squares in the days following the coup d’etat attempt on July 15th, 2016.

In most of my mapping work, I simply investigate data about one critical relation that connects many agents and constitutes more power as it scales. When completed, a data network is formed and I put that particular world to use.

CM: MyPocket discloses your personal financial records to the internet public by exploring essential patterns in your transactions and deploying software to analyse those transactions. The software, which predicts future spending, sometimes determines your future spending choices. Mark B Hansen calls this a “feed-forward” relationship—one where statistical forecasting, future prediction, and probability calculation can code user behaviour “ahead of time,” framing the future-oriented choices of a subject.

What is an example of a consumer choice you’ve exercised that you were directly influenced to make by this software prediction? Did knowing that your personal financial data was being tracked impact your financial management or change your spending behaviors at all?

BA: MyPocket software was able to successfully predict when and where am I going to buy coffee. It predicts ordinary futures. Our lives have such repetitive patterns, which are not so hard to guess right for a supervised algorithm. With MyPocket, I put myself in an experiment of living under excessive forecast about my everyday purchasing behavior. Would I change my habits, would I abide by the predictions, would I care, would I notice, would I ignore? All of these applied at various stages as I lived with this software system for 2 years.

Today, protecting your privacy is akin to quitting smoking or exercising a vegan lifestyle. Changing habits is clearly hard, but once it starts rolling, it causes a big positive change. I believe, in a society of control that monitors, simulates and pre-mediates individual identities in relation to their data trails, behavioural dissidence is superior to reactionary resistance.

CM: You are an artist and technologist. Does one of these identities emerge more frequently in your work? Did your programming skills drive you to explore the aesthetic possibilities of networking mapping? Was there a sequential logic to your artwork as a secondary and subsequent extension of your work in the computational sphere? How do you situate your artistic practice—one that is reliant on a high degree of technological literacy—to the tools of computer technologies?

BA: My art making is a subjective exploration raising questions, whereas my tool making always wants to be objective, tapping an issue with a solution. I practice them in parallel and they feed each other. Making tools helps me examine all kinds of infrastructures closely thus provides lenses for new questions in my artwork. Artistic inquiries help me change my beliefs about the world.

In the first class of an introduction to computer programming course at MIT, students are told that programming is unrelated to computers in a way that geometry is unrelated to geography. Mastering programming takes years. In fact, in my very early work, technology and algorithms had authority on the outcome, whereas later works have been freed from technological capacities.

BA: Do you find that the procedures for mapping with non-digital tools change your artistic strategies and the types of networks you produce? In a similar vein, is the medium of Graph Commons as a digital interface important to the co-collaborative possibilities that this online platform enables? Would you describe the network mapping that Graph Commons enables as an act that is inherently political, or aligned with activist models of representation?

BA: I always start modeling an idea by sketching on a paper, by discussing with people, by taking notes here and there. It is often a contemplative process that I don’t find possible in a digital tool. As the idea gets mature, the amount of related material might not be manageable on paper – then I start organizing it using digital tools, write some code to scale it and observe its extents.

Obviously, digital tools on the Internet are best for asynchronous communication. The Graph Commons data mapping and publishing platform is great for internet-scale data mapping collaborations. Network mapping particularly is a powerful tool, it makes things more transparent. So activists, journalists, researchers, and civil society organizations around the world use it to untangle complex relations that impact them and their communities.

CM: Do you see networks as maps? Monovacation seems to deploy features of both in its networked parody of the commodity forms and repeated images that characterize the tourism commercial as a typology. What are some key distinctions that might separate these two forms from one another in their attempts to frame, visualize, and enclose data?

BA: As I mentioned earlier, I use network as a map vs network as an event separately in my work.

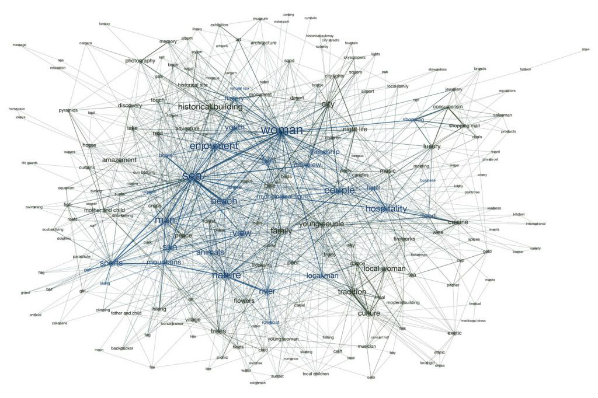

Monovacation introduced network traversal as a method to deconstruct and explore movies as databases. The official tourism commercials of countries in competition with each other have been selected and each film has been divided into the possible tiniest clips. The 3-4 second long clips have been coded with tags. Tags with shared clips are connected to each other (weighted with number of clips) on a network diagram, which runs as a self-organizing software simulation. A new movie has been algorithmically generated through a traversal on this network map, a program navigating from one node to another, following the weighted path among the tags. Seashores from Egypt to Portugal, women from Israel to India, mythological figures from Thailand to Turkey formed an extracted fantasy of “vacation”.

CM: The Graph Commons platform contains an additional axis that static graphics do not: time. How does working within digital media open up new models for orienting the user within data collections, particularly where the ability to represent change-over-time is at play?

BA: Networks are inherently dynamic, undergoing constant changes, both within the composition of nodes, and in the relations between nodes. To help you understand how the network changes and behaves over time, Graph Commons provides a timeline interface. It animates your network map as nodes leave and enter the network and the map expands or contracts in time. The network shape, radius, density, intensity, and emergence of clusters, central and peripheral actors all become observable and comparable using the timeline feature.

CM: Networks are the predominant and paradigmatic episteme of the information age. What kinds of relationalities, phenomena, data collections, or texts do they fail to capture? In other words:

a. What the network is NOT suited to do/perform

b. On speculating through an accelerated lens, what will the predominant formal and organisational structure of the next century look like? Will networks continue to play a role, or will they be completely surpassed by new organisational and structural logics?

BA: Bare network mapping may not be sufficient in studying multilayered diverse network dynamics where actors (nodes) and relations (edges) is not clearly distinguishable from one another as in swarms of species or molecular activity. Moreover, at the heart of capturing data lies the question of measurability. If something analogue can be measured it becomes digital, then it can be linked to other data points and become a subject of a network analysis. I think in this day and age, even emotions, intentions, and desires could be measured to a degree, if not socially reproduced.

In a world where every atom can be addressable with an IP address (IP6), discussion of the possibility of capturing analogue things is increasingly less relevant. What becomes critical is the question of who captures and controls what data owned by whom. Do you own a self-driving car’s data captured from your neighbourhood? Are you in control of your data captured by the network medicine? Are you paid rent for the use of data that belongs to you? Data oligarchies will only continue to grow, and this situation of data dispossession will increasingly constitute what I call data asymmetry for many years to come, until we move from connectivity to collectivity, build purposeful exploitation-free autonomous zones, and reroute our life activities in solidarity.

Regarding the future of organizational structures as imagined to be constituted by cryptocurrencies, something clear from today is that decentralization is not necessarily democratic. It should be deliberately discussed that ones who design the protocols have power and network effects can generate inequality. A blind belief in decentralization would not be so different than a belief in free market ideology. When Poland, Chile, and Turkey opened their markets to the world in the 80s, globally networked corporations penetrated into these markets completely within the laws and yet left the small locally connected actors stagnant, this is one example how network effects could generate inequality.

Basic Income is often promoted as an idea that will solve inequality and make people less dependent on capitalist employment. However, it will instead aggravate inequality and reduce social programs that benefit the majority of people.

At its Winnipeg 2016 Biennial Convention, the Canadian Liberal Party passed a resolution in support of “Basic Income.” The resolution, called “Poverty Reduction: Minimum Income,” contains the following rationale: “The ever growing gap between the wealthy and the poor in Canada will lead to social unrest, increased crime rates and violence… Savings in health, justice, education and social welfare as well as the building of self-reliant, taxpaying citizens more than offset the investment.”

The reason many people on the left are excited about proposals such as universal basic income is that they acknowledges economic inequality and its social consequences. However, a closer look at how UBI is expected to work reveals that it is intended to provide political cover for the elimination of social programs and the privatization of social services. The Liberal Party’s resolution is no exception. Calling for “Savings in health, justice, education and social welfare as well as the building of self-reliant, taxpaying citizen,” clearly means social cuts and privatization.

UBI has been endorsed by neoliberal economists for a long time. One of its early champions was the patron saint of neoliberalism, Milton Friedman. In his book Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman argues for a “negative income tax” as a means to deliver a basic income. After arguing that private charity is the best way to alleviate poverty, and praising the “private … organizations and institutions” that delivered charity for the poor in the capitalist heyday of the nineteenth century, Friedman blames social programs for the disappearance of private charities: “One of the major costs of the extension of governmental welfare activities has been the corresponding decline in private charitable activities.”

To Friedman and his many powerful followers, the cause of poverty is not enough capitalism. Thus, their solution is to provide a “basic income” as a means to eliminate social programs and replace them with private organizations. Friedman specifically argues that “if enacted as a substitute for the present rag bag of measures directed at the same end, the total administrative burden would surely be reduced.”

Friedman goes on to list some the “rag bag” of measures he would hope to eliminate: direct welfare payments and programs of all kinds, old age assistance, social security, aid to dependent children, public housing, veterans’ benefits, minimum-wage laws, and public health programs, hospitals and mental institutions.

Friedman also spends a few paragraphs worrying whether people who depend on “Basic Income” should have the right to vote, since politically enfranchised dependents could vote for more money and services at the expense of those who do not depend on these. Using the example of pension recipients in the United Kingdom, he concludes that they “have not destroyed, at least as yet, Britain’s liberties or its predominantly capitalistic system.”

Charles Murray, another prominent libertarian promoter of UBI, shares Friedman’s views. In an interview with PBS, he said: “America’s always been very good at providing help to people in need. It hasn’t been perfect, but they’ve been very good at it. Those relationships have been undercut in recent years by a welfare state that has, in my view, denuded the civic culture.” Like Friedman, Murray blames the welfare state for the loss of apparently effective private charity.

Murray adds: “The first rule is that the basic guaranteed income has to replace everything else — it’s not an add-on. So there’s no more food stamps; there’s no more Medicaid; you just go down the whole list. None of that’s left. The government gives money; other human needs are dealt with by other human beings in the neighborhood, in the community, in the organizations. I think that’s great.”

To the Cato Institute, the elimination of social programs is a part of the meaning of Universal Income. In an article about the Finish pilot project, the Institute defines UBI as “scrapping the existing welfare system and distributing the same cash benefit to every adult citizen without additional strings or eligibility criteria”. And in fact, the options being considered by Finland are constrained to limiting the amount of the basic income to the savings from the programs it would replace.

From a social welfare point of view, the substitution of social programs with market-based and charitable provision of everything from health to housing, from child support to old-age assistance, clearly creates a multi-tier system in which the poorest may be able to afford some housing and health care, but clearly much less than the rich — most importantly, with no guarantee that the income will be sufficient for their actual need for health care, child care, education, housing, and other needs, which would be available only by way of for-profit markets and private charities.

Looking specifically at whether Friedman’s proposal would improve the conditions of the poor, Hyman A. Minsky, a renowned and highly regarded economist, wrote the “The Macroeconomics of a Negative Income Tax.” Minsky looks at the outcome of a “social dividend,” which “transfers to every person alive, rich or poor, working or unemployed, young or old, a designated money income by right.” Minsky conclusively shows that such a program would “be inflationary even if budgets are balanced” and that the “rise in prices will erode the real value of benefits to the poor … and may impose unintended real costs upon families with modest incomes.” Any improved spending power afforded to citizens through an instrument such as UBI will be completely absorbed by higher prices for necessities.

Rather than alleviating poverty, UBI will most likely exacerbate it. The core reasoning is quite simple: the prices that people pay for housing and other necessities are derived from how much they can afford to pay in the first place. If you imagine how housing is distributed in modern capitalist society, the poorest get the worst housing, and the richest get the best. Giving everyone in the community, rich and poor alike, more money would not allow the poorest to get better housing, and it would just raise the price of housing.

If UBI came at the expense of other social programs, such as health care or child care, as Friedman intended, then the rising cost of housing would draw money away from other previously socially provisioned services, forcing families with modest incomes to improve their substandard housing by accepting worse or less childcare or healthcare, or vice versa. A disabled person whose mobility needs requires an additional expenditure on accessible housing may not have enough of the basic income left for any additional health care they also require. Yet replacing means testing and special programs that address specific needs is the big idea of UBI.

The notion that we can solve inequality within capitalism by indiscriminately giving people money and leaving the provisioning of all social needs to corporations is extremely dubious. While this view is expected among those, like Murray and Friedman, who promote capitalism, it is incompatible with anticapitalism. UBI will end up in the hands of capitalists. We will be dependent on these same capitalists for everything we need. But to truly alleviate poverty, productive capacity must be directed toward creating real value for society and not toward “maximizing shareholder value” of profit-seeking investors.

Many people don’t dispute the fact that establishment promoters of UBI are only doing it to eliminate social programs, but they imagine that another kind of basic income is possible. They call for a basic income that disregards the “deal” that Charles Murray advocates but wants UBI in addition to other social programs, including means-tested benefits, housing protections, education and child care guarantees, and so on. This view ignores the political dimension of the question. Proposing UBI, in addition to existing program mistakes, a general consensus for replacing social programs with a guaranteed income for a broad support base for increasing social programs. But, no such broad base exists.

Writing in 1943, with the wartime policies of “full employment” enjoying wide support, Michal Kalecki wrote a remarkable essay entitled “The Political Aspects of Full Employment.” Kalecki opens by writing, “a solid majority of economists is now of the opinion that, even in a capitalist system, full employment may be secured by a government spending programme.” Though he is talking about full employment, which means an “adequate plan to employ all existing labour power,” the same is true of UBI. Most economists would agree that a plan to guarantee an income for all is possible.

However, Kelecki ultimately argues that full employment policies will be abandoned: “The maintenance of full employment would cause social and political changes which would give a new impetus to the opposition of the business leaders. Indeed, under a regime of permanent full employment, ‘the sack’ would cease to play its role as a disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be undermined, and the self-assurance and class-consciousness of the working class would grow.”

The conflict between the worker and the capitalist, or between the rich and the poor, can not be sidestepped simply by giving people money if capitalists are allowed to continue monopolising the supply of goods. Such a notion ignores the political struggle between the workers to maintain (or extend) the “basic income” and the capitalists to lower or eliminate it to strengthen their social position over the worker and to protect the power of “the sack.”

Business leaders fight tooth and nail against any increase in social benefits for workers. Under their dominion, only one kind of UBI is possible: the one supported by Friedman and Murray, the Canadian Liberal Party and all others. They want to subject workers to bosses. The UBI will be under constant attack. Unlike established social programs with planned outcomes that are socially entrenched and difficult to eliminate, UBI is just a number that can be reduced, eliminated, or allowed to fall behind inflation.

UBI does not alleviate poverty and turns social necessities into products for profit. To truly address inequality we need adequate social provisioning. If we want to reduce means testing and dependency on capitalist employment, we can do so with capacity planning. Our political demands should mandate sufficient housing, healthcare, education, childcare and all basic human necessities. Rather than a basic income, we must demand and fight for a basic outcome — the right to life and justice, not just the right to spend.