Parrots. Grey parrots. African grey parrots. African grey parrots laughing. I hear African grey parrots laughing. I hear African grey parrots laughing and it’s weird.

Their laughter sounds forced. Not compulsive, no, it’s not that. But artificial to say the least. Somewhat robotic. And I find it rather disturbing.

I can also hear birds chirping outside, and their sound is clearly different. Their tone of voice is lively and high pitched. And it brings me joy, almost subconsciously.

However, as I begin to doubt the authenticity of the African grey parrots’ laughter, I am told that their laughter is real. They are real parrots that are truly emitting the sound of laughter: they have been trained to do so.

The history of the process that leads me to listen to this laughter spans over a period of sixteen years. Sixteen years during which the Slovenian artist Sanela Jahić has produced works that have reversed the power balance in the world of work (Five Handshakes, 2016), explored the range of emotions within the human-machine relations in industrial workplaces, (The Factory, 2013), studied the history of gesture efficiency in factories (Tempo Tempo, 2014) and created the conditions for experiencing human-machine co-creation (Fire Painting, 2010). However, over the past three years she narrowed her focus to applying automation to her own practice. Since these prosthetic technologies pervade the capitalist world of work—through the increasing replacement of workforce by industrial robotic arms and systems as well as through the increasingly algorithmic management of workers—why should it not be applied to the production of artworks? A seemingly light-hearted question that allows the artist to raise another, deeper question: can artistic creation be considered on the same level as other types of work? And ultimately, what does it mean to cast off the burden of choice to machines, what does it mean to try to distance oneself from one’s subjectivity while consciously choosing to delegate one’s decisions to a computer program?

Responding to generalized quantophrenia1—from permanent, automatized and unsuspected data extraction to voluntary submission to the fascinating and oxymoronic idea of the quantified self, i.e. a human being reduced to mere numbers—Sanela Jahić started to conceive a way to turn her career into numbers. She created a classification system which she applied to all of her artworks and through this produced a database of her works. A selection of parameters described as keywords represented numerous different aspects of her work such as ‘manual labour’, ‘mathematical precision’, ‘mechanical device for showing images’, ‘collaboration’, ‘mistake as a sign of the human factor’, ‘revealing patterns’, ‘mechanism in the back’, ‘machine painting’, ‘light-based medium’, and many more; their intensity was displayed in graph form in a series of works titled The Labour of Making Labour Disappear (2018). But this would not present sufficient data for an algorithm to create a work on Jahić’s behalf, since this new work would have been based merely on the previously created works, and not on what would have actually taken place in the artist’s mind at the moment of creation.

In order to overcome the potentially simplistic predictive outcome, Jahić decided to complete the database with elements that would have probably influenced her. Thus, she added approximately six months of real time data on what she was reading while working on this project to the parameters. Every word from every text that passed in front of her eyes increased the database, opening new horizons of thought. With this amount of technical, theoretical, sociological and descriptive terms, ranked by the frequency of their occurrences, the algorithm was set to act as a surrogate of her creative endeavour.

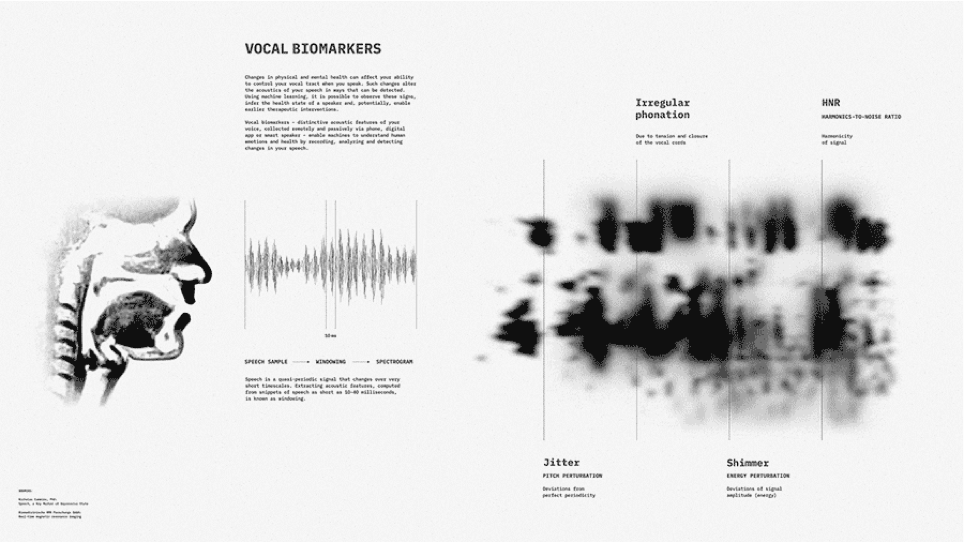

According to the artist, if we consider this process as a (psycho)analysis of her work, we can also ironically read it as an analysis of the prediction algorithm by itself. Indeed, the algorithm specifically designed2 for the occasion, produced output terms such as: ‘behavioural data’, ‘tracking devices’, ‘scientific investigation’, ‘assessment tool’ and ‘machine learning’. ‘Vocal biomarkers’ also came up. Vocal biomarkers are a diagnostic tool used by artificial intelligence systems that scan for voice patterns in speech with the aim of detecting diseases such as depression, cancer, or heart conditions with the aid of a database of intonations linked to predetermined underlying emotions. This speech signal analysis focuses on the tone of voice and therefore does not require the spoken words to be numerous or even to make sense, which is why individual words can be used as vocal exercises that provide the necessary data.

Pataka is one of these words. Found in the Mapuche language in which it means a hundred, as well as in Hindi where it designates firecrackers, the word Pataka, when pronounced, asks the speaker to emit rapidly alternating sounds which allow for precise detection of their muscle control, the lack of which is a common sign of depression.

Since Sanela Jahić had to interpret the predictive results from the algorithm in order to turn them into an artwork in its own right, she chose to work around the use of this specific word3 but not to work with people afflicted by illness; thus she decided to use parrots as proxies. Parrots are known for imitating the voice of the persons teaching them to speak, and this can be seen in Jahić’s Pataka videos. Parrots. Grey parrots. African grey parrots. African grey parrots talking. And African grey parrots laughing.

Sanela Jahić, Uncertainty-in-the-Loop, Aksioma, Ljubljana, 23 September – 23 October 2020, and Delta Lab, Rijeka, 5–27 November 2020.