MONODROME: Art’s debt in times of crisis

AB3 Athens Biennale 2011 Monodrome

Curated by Nicolas Bourriaud and X&Y

23 October-11 December 2011

Athens Biennale 2011 was the third edition of this institution and was entitled “Monodrome”, meaning “One way street” after the 1928 text “Eisenstrasse” by Walter Benjamin. The concept of the title is obvious; after the first Athens Biennale in 2007 prophetically entitled: “Destroy Athens”, the second Biennale “Heaven” in 2009, “Monodrome” comes as a closure to this trilogy. Why Walter Benjamin? Because he was a “defeated intellectual”, according to the curators. German-Jewish philosopher, an emblematic figure of 20th century thought, gave an end to his life at the french-spanish border while trying to escape the Nazis. “He was unable to overcome his personal dead-end as a subject”, says Poka-Yio of X&Y and he continues: “The title of this exhibition after Benjamin’s text refers to a collective dead-end” currently at stake and it’s only possible fate: a cloud of doom. “Monodrome” aimed to provoke debate around “something that has fallen apart, but to also offer the possibility of a glimpse at something new to come”.

Indeed, this Biennale took place at a specific moment in Greek and global history, where all 20th century utopian narratives (i.e. modernism, ecology, metaphysics) are crashing, introducing to the whole world a humiliating and disturbing, both socially, as well as nationally, dystopian non-future. Athens, the cradle of democracy was – at the time – “rocking the world”, by suffering the experimental imposition of a non-democratic supernational regime stamped with the mark of over-privatization, a situation that immediately started spreading all over Europe. Now – that the exhibition has come to an end – nearly everyone on this planet feels that “the time” {our world – as we know it – has come to} “is out of joint”, “the very place of spectrality” (Jaques Derrida, “Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International“ Routledge, 1994: 82).

What’s art got to do with this? “Artists usually have premonitions of what’s going to happen, it is often that artists precede with their work social changes; artists are mostly intuitive, it’s at the core of their existence, this how they create” Poka-Yio says. Nicolas Bourriaud and X&Y had to deal with a situation that can be called no less than a “crisis management”. The exhibition was organized practically with no funding and was based mainly on the contribution of all participants and volunteers. The social events that were taking place during the very opening of the show were probably amongst those of the most significant importance in Greece’s postwar history. The energy and emotional vibe caused by this historical moment were the background of the Biennale and made it both a great challenge and a responsibility for the curatorial team.

Despite these critical financial and social circumstances, the Biennale was successfully realized against all odds and it can be said, that it was well received by the audience – an accomplishment on behalf of the curators who selected the works, planned and organized it. The curators of the 3rd Athens Biennale 2011 felt that “the widening situation for which Greece is a much derided yet overexposed case-study must become the focus of cultural investigation, in a way that it is no longer poignant – or even moral – to simply keep making exhibitions in the way that had become the norm in previous years”.

In order to address these issues, besides investigating the exhibition’s conceptual framework, the curators decided “to experiment with the Biennale exhibition format itself, by transforming it into an invitation to create a political moment rather than stage a political spectacle by making a call to a sit-in of collectives, political organizations and citizens involved in the transformation of society”. At another level, as the exhibition was designed and produced, its various stages of development were providing the basis for a feature film directed by Nicolas Bourriaud. Social media also played an important role in the communication strategy of this Biennale, as every event, talk, happening or performance was recorded and presented at AB3 youtube channel and one could follow it via facebook, twitter and other social platforms, as vimeo, flickr and tumblr.

The conceptual framework, upon which the theoretical thread was build, was a deep dive in the folds of Greek history. The curatorial strategy chose “to represent an ongoing crisis through historical fragments, a Benjaminian technique”. Walter Benjamin, provided with his text “Eisenstrasse” the tools for looking at history in a fragmented way, for he, according to the curators, introduced theoretical tools for looking into history with terms of “here and now”, by often making references to the city and to the popular culture of his time. “One way to talk about history is to include history”, says Nicolas Bourriaud. “The exhibition was structured as text; its narrative unfolds as one searches in the ruins and tries to read their meaning”, as one “tries to find out about new possibilities of giving meaning”.

Walter Benjamin, as a character, for the needs of this exhibition’s narrative concept was brought in a paradox dialogue with another character, a fictional one: Saint Expery’s Little Prince. This narrative plot brings this real life character, the emblematic intellectual, to meet the hero of a children’s novel, because: “a child can pose questions in an intelligent manner representing the inner child to be found in everyone” says Xenia Kalpaktsoglou of X&Y team of Athens Biennale co-founding curators. Little Prince poses all fundamental questions of “being” to the philosopher and the intellectual strives to give back the right answers. This imaginary dialogue took place in the form of sketches spreading like a graffiti-comic all over the walls of the exhibition’s main venue building. “As the intellectual retreats defeated in the face of the escalated distress, the Little Prince keeps questioning this condition with the disarming innocence and the plainspoken boldness of a child”.

The real protagonist of the exhibition, however, was Diplareios School, the main venue, a nearly disused old building located at the heart of downtown Athens in an underprivileged area, right across the City Hall and the old big open market. The local color and the smells of the market square, crowded with immigrants, ethnic shops and – especially at night – the presence of junkies, dealers and prostitutes was part of the exhibition’s “aura”. This building was literally used as a “panopticon” of both contemporary and ancient Athens and has a long history. It was built for the purposes of housing a School of Design, meant to be “the Greek Bauhaus”. Among many of its uses, it was requisitioned during the German Occupation and during the time when Athens was so badly over-built, it was hosting the offices of Urban Planning public service. The second exhibition venue was “Venizelos Museum”, a former military basis also used during the Greek dictatorship as the headquarters of torture investigating anti-regime citizens (former ΕΑΤ – ΕΣΑ).“The space is the artwork”, Bourriaud says. “Not just a venue. It’s previous functions manifest its character; it is a real protagonist”.

Diplareios School is an allegory of modern Greece surrendering itself to abandonment. Looking around all one sees is worn walls and graffiti, all one hears are the voices of protests and the ubiquitous noise of the city. The curatorial strategy for this Biennale was quite different from the two previous exhibitions, “Destroy Athens” in 2007 and “Heaven” in 2009. No big names of the international art market to be found among the artists. No self-referential patterns in this exhibition, other than “questions on the reasons behind the political crash, the crisis of moral values, the dead-end”. It was in fact a much more “introvert” exhibition, focused on the local scene, featuring mainly emergent Greek artists. The exhibited artworks in their majority came form Greece: “to include the local, to talk about local artistic production was one of our aims for this exhibition” according to Bourriaud.

Only to mention a few, Spyros Staveris, an emerging Greek photographer with a video art photo-documentation following the “Aganaktismenoi” social movement in Athens at its very birth. In the same room, “Ηommage a Athenes” a sound installation by Vlassis Kaniaris, with recorded sounds of the recent Athenian protests. One could not but mention the remarkable work of young Greek sculptror Andreas Lolis who is making cartboard boxes and felizol sculptures out of marble. “In my artwork, I try to make time stop. The reason why I am using marble, is because I want to make these fragile objects eternal”. “We all use cartboard boxes. People sleep in them. When I looked down from the windows of the Biennale venue and saw people on the terraces sleeping in cartons, it only came to me as a natural thing to co-exist with this situation – not to record it”. “This is the best time for Art. Not the art market, Art. When I recently saw the artworks of Athens Fine Art School graduates, I realized that the bubble-effect’s gone, now. These young artists, living this situation have grown into reality. There’s so much truth in their artworks”.

Another captivating artwork featured at the Biennale was “EXIT” by the Greek collective “Under Construction”, an installation of old rusty worn office desks; “in fact we present an allegorical image of Greece, using old equipment of public services, eroded now from abandonment. The hard to distinguish faded “EXIT” ‘statement’ does not exist, at least not literally”.

Rena Papaspyrou’s “Photocopies” is another stunning installation, where phone numbers printed on fragments of paper are posted on the wall. “Extending the decay of the wall, this piece secretly interacts with the graffiti notes on the wall waving alternative histories of the numerous uses of the building”. Thus the interaction between Papaspyrou’s installation and the Diplareios building creates a sense of dialogue, both in concept as well as in form.

One may wonder whether any international artists were presented in this exhibition. Lucas Lenglet, Jakob Kolding, Norman Leto, Caroline May, Josef Dabernig, Józef Robakowski only to mention a few, and of course, Julien Prévieux’s “A La Recherche du Miracle Economique”.

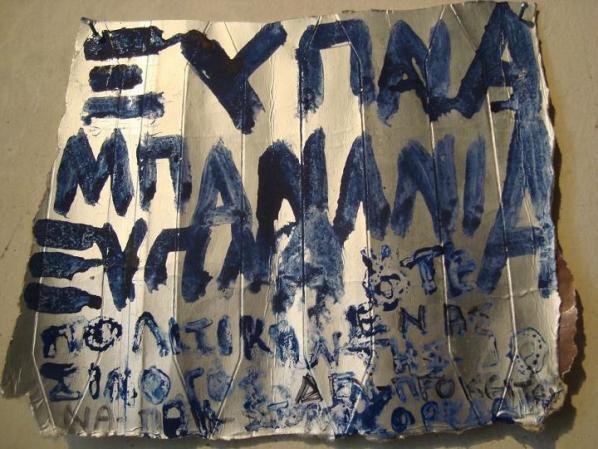

“This is a fragmented exhibition”, Bourriaud says: “one can see in this exhibition various media, film, collages, photographs, sculptures, drawings, paintings”. Amongst the artworks, the visitor would encounter several objects that have nothing to do with art but were used as tools for the exhibition narrative: a time lapse, a trip down to memory lane. For example, an object used for this purpose was a placard, that the curators found discarded after a recent protest in Athens. On the placard was written: “WAKE UP BANANA REPUBLIC”.

Also, the lost opportunity of Greek design; some of the works of students of Diplareios School were exhibited; they had been left in the old School. Posters by Greek National Tourism Organisation by Michael and Agnes Katzourakis. Pictures of Andreas Papandreou with Gaddaffi during the “good old days”. Air stewart and pilot uniforms from The Olympic Airways. In the attic of the old School, the crescendo of the exhibition’s narrative: as one faces the image of the ancient monument of the Acropolis through the dirty windows of the old School, a dead pigeon that was found there and was respectfully kept by the curators as a symbol, an omen.

The 3rd Athens Biennale 2011 was a double project; in both the form of an international exhibition and a feature film. The return of Walter Benjamin as a ghost that comes to haunt the city of Athens during this crisis period is the theme of a film directed by Nicolas Bourriaud. “It is a feature film, a film as an exhibition, a documentary based on actual characters, a docu-fiction and an experimentation with the platform of the Biennale”, says Bourriaud. “The film will be a work of fiction albeit based on real events. This is the first time that the relationship between contemporary art and filmic language is investigated in this way”. A catalogue will document the whole process of the 3rd Athens Biennale, and a DVD edition, including the movie and documents on participants’ works, will be published. Following the completion of the Biennale, the film in its final format will be distributed both in the art world and the cinema circuit. The executive producer of the movie is Kino Prod (www.kino.fr) in Paris.

Ironically, and sadly, “Monodrome“’s TV trailer was censored by the Greek National Broadcaster (ERT), who was also the major communication sponsor of the Biennale. The director of this 26’’ spot, Giorgos Zois, a talented young Greek filmmaker who has already won several international distinctions and prizes – according to his official statement as an answer to this act – attempted to “deliver the theme of the 3rd Biennale MONODROME (meaning one-way) in a series of slow-motion images of a forcibly accelerated reality depicting the one-way contemporary condition. Instinctively and suspiciously the national Greek television judged the content to be against the law that forbids “messages that contain elements of violence, or encourage dangerous behaviors, or insult human dignity”. “Apparently the daily transmission of aggressive porn-like governmental policies, does not count as an insult to viewers”. You can watch the trailer here: