To many, technology and spirituality would seem antithetical. Contemporary technology is intertwined with modern science, whereas, spirituality is equally enmeshed within both religion and faith. The Post-Human Gospel self-consciously accepts this awkwardness, and manoeuvres these two uneasy bedfellows together. Offering up a night of performances, by artists whose entangled relation to technology seeks to posit new forms of identity and spirituality.

This is the latest in a series of events, collectively entitled Syndrome, seeking to explore the relationship between technology and affect in performance. The Post-Human Gospel marks the start of the third phase of this activity, collaboratively programmed by Mercy and The Hive Collective. If 3.0 is heading into the realm of spirituality, then earlier phases have played with both language and control – whether the constraints enforced on the body in virtual space, role-playing authority within the State Free State of a.P.A.t.T island, or a ‘room as instrument’ where you can physically manipulate sound and light. Across these events, those involved ask how we might interact or play with this technology, and in turn, how this experience might then act upon on us – our feelings and emotions?

The venue at 24 Kitchen Street has played host to several past Syndrome events, and as such feels like a hub for this activity as it meanders across the city. Arriving early there is a relaxed feeling to the space: people stand around chatting, whilst others tinker with equipment and final set-up, all bathed within the blue glow of the expectant projection screens. There is a familiarity to the space on a number of levels – not only physically, with decaying white walls and exposed structure typical of the post-industrial use of such buildings, but also in terms of its unclear typology, part-bar, part-residency-space, part-performance-venue, part-something-else-entirely. An earlier performer, Mathew Dryhurst, described a type of ‘third space music’ that requires a new type of venue. Something that Syndrome is clearly looking to create in Liverpool.

The evening’s Gospel was tripartite, starting with SHRINE by Outfit, followed by a first-time collaboration between Lawrence Lek and Siôn Parkinson, and then brought to a close with a live AV set by TCF. All performed from a improvised V-shaped altar – constructed from scaffold, screens, speakers and an array of other equipment – and oriented to the rows of the largely seated congregation.

A live performance-cum-guided-meditation, SHRINE was made in collaboration with the band Outfit and performed by lead guitarist Nick Hunt. Against the backdrop of a consistent electronic hum, the light of multiple projections alternates to produce a strobe-like effect. After the instruction to close our eyes, a distant reverberant monologue begins: “What is the meaning of asteroid? What is the meaning of baptism?” The warm flicker on the interior of the eyelid creates a soft trance-like state and the potential hypnotic suggestion washes over us. The minimal rhythmic repetition of this basic structure continues, but strays further and further from these initial references. What is the meaning of blurred lines? … Chandelier? … D-Day? … FIFA? Alliteration and rhyming abound. Selfie. Sophie. Stonehenge. Peter Pan. Quran. Ramadan. There is an emptying out of meaning, and a breakdown of language. KKK … K. The voice has a haunted quality, that of an entity in a state beyond being human. Perhaps it is the voice of the network, which the monologue refers to as ‘watching over us’, of ‘being busy’. It promises a revelation that is coming, that is now, another world, one that we don’t reach. Ultimately it leaves us cleansed, or rinsed out. Then I learn that the work was written with the assistance of Google Instant predictions, hence the alphabetical concatenation of words. Not so far from the network watching over us after all.

Lawrence Lek and Siôn Parkinson’s performance is the result of a short residency leading-up to the event, and therefore has a more involved relation to Syndrome. This residency structure is a recurring feature of the programme, with past residents including K回iro (Holly Herndon and Mathew Dryhurst), and before that Jamie Gledhill and Stefan Kassozoglou. Whereas these past examples involved existing partnerships, Lek and Parkinson’s collaboration was the first time that Syndrome brought together two artists, placing Parkinson’s vocal performance inside the digital landscape created by Lek.

A simulation of Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral frames the performance, and provides an imagined perspective on this familiar architecture. Starting from a removed position – with the spectral cathedral in the distance – we roam through a wood, trees blowing in the wind. This landscape glitches in a way familiar to the experience of online or virtual worlds, and is accompanied by a soundscape produced by Lek on guitar and electronics. Gradually approaching our destination, bells peal, and further sounds produced begin to resemble those of an organ, groaning and droning as we enter its interior. Parkinson’s body is silhouetted against the projected architecture, his head bathed in red light and his voice rising as Lek’s audio recedes into the background. An otherworldly sermon tells of teeth wrenched out from a mouth to form the keyboard console of the church organ. Moving from sung to spoken word, to deep guttural noises. Rumbling bass emanating from the body, amplified, and shaking the room. Lek’s guitar returns, and there is the liquid crackle of noise as water rolls down the walls, and fire inhabits the projected interior. Our point-of-view rises high above the cathedral, and we see it situated in a landscape abundant with lakes and islands, like some stretched-out fantasy where this iconic building is removed from its physical context – as though transplanted from Liverpool to another world.

These mystical images continue through to the final performance by Lars The Contemporary Future Holdus (TCF). Projecting an increasingly entangled use of technology, he plays with encryption, code and algorithms to construct a subdued visual and sonic space. Twisted and distorted beeps shudder as fragments of sound screech and scrape along the digital surface, and liquid forms slip across the projected image. This precise construction appears to breathe, the sonic utterances repeatedly sucked back inside themselves as the molten amorphous form visually expands and contracts like something from within the bodily interior. There are moments where a mouth/voice emerges, a digital blob talking to us in a language that we cannot comprehend. Behind this audio-visual surface there is something else going on, something that Lars Holdus is engrossed within as he operates the TCF system – tinkering with the algorithm to progress through a series of potential compositions. Yet despite this, I feel largely disconnected – lacking in empathy – as though missing something in what is going on. There is an evident penchant for the opaque, that creates a distance between TCF and the audience, potentially even alienates. This is acknowledged by the artist, who states: “even the presentation is an encryption in itself. And therefore the people that won’t be triggered like that won’t access it.”1 I clearly fail to trigger, and my access is denied.

Syndrome is creating a space for artists, musicians and coders to experiment with work that merges electronic music and spoken word performance. The affordance offered by the flexibility of the venue has allowed an approach that would not have been possible within a space in daily use. These latest performative responses make clear that is it not about offering concrete proposals about what is going to happen, before they have time to come into being. Rather, what we witness is artists playing with the resources available, and figuring out what these things might do to us. There is a genuine openness and a potential intimacy to this approach, as well as the acceptance that the results will not always connect or affect audiences in the ways that they might be hope.

Different types of voice seem central to the three works presented within The Post-Human Gospel, affecting the human vocal output as well as trying to give voice to instruments, electronics and digital space. There is something in this that Holly Herndon has described as a “fleshy approach to machinery”, where these digital tools can take on a post-human quality, one that can become or embody different identities. This looks set to continue with the forthcoming event Brain/Music Experiments where artist Dave Lynch, neuroscientist Christophe de Bezenac and deaf classical musicians Ruth Montgomery and Danny Lane explore the ways a brain wave scanner can contribute to live music and visual performance.

The intention for Syndrome is to learn from all the visiting artists and the performances they create in this exploratory year. Looking for moments when performances create affective interfaces to communicate with people. Where they speculate on, or re-conceive, the relationship between human and technology. If they go on to develop a new live experience with the artistic community that surrounds Syndrome – as they suggest they will – I look forward to experiencing how the cumulative knowledge built up through these earlier events is harnessed to final affect.

Pencil / Line / Eraser, the current exhibition at Carroll/Fletcher, spanning both the main Eastcastle Street gallery and their nearby Riding House Street project space, is well worth a visit. It’s never less than engaging and there are several pieces that lodge, linger and ferment in the mind long after the bus or train ride home.

They describe the show as “surveying recent works in expanded drawing which use paper and line as a point of departure” and, let me say again, whatever I have to say that is critical you won’t waste your time there. Far from it.

This review will be in two parts – first, & with an innocent(ish) eye, I’ll sing the praises of the work that itself sang to me during my visit and then I’ll vent about the things that irritated me, more a question of contextualisation and commentary than of the work itself, although in today’s text ridden and intention trumpeting artworld it’s sometimes a little difficult to unpick one from the other. Since the artists cannot completely escape responsibility this has consequence for any assessment of some of the work.

In a space of their own, a little into the main gallery, there are three pieces by the Portuguese artist Diogo Pimentão and they are delicious – large pieces of heavyish paper covered with graphite and folded, draped and rolled. Two are delicately attached to the wall so they appear to float there and the third sits up on the floor like a long fierce graphite flue.

The works capture superbly paperishness: its particular foldiness, rolliness and drapiness and its ability to suck up pigment in large quantities (fields rather than lines here) Indeed the graphite covering softens the folds and creases so what we experience is a kind of Platonic report on the qualities of paper. The urge to touch this gorgeousness is almost irresistible.

The works strongly recall Richard Serra (though what I perceive as his machismo is entirely absent) – his early large scale drawings using a single dark medium, ink or oil stick, but also the torque and defiance of gravity that is so much part of the steel pieces. I’ve no idea whether this is a conscious borrowing but to point it out is not to criticise the work in any way because it feels like a commonality of subject matter –the stuffness of stuff – rather than technique, despite deceptive (and magically so) similarities of appearance. (It takes a couple of beats to fully realise that Pimentão’s work is work on paper and not something else.)

Further along to the left in the stairwell is one of a number of films by Wood and Harrison. Some of their work strikes me as a tad glib – smart but somehow too undemanding of thought and which tickles the viewer’s tummy (and amour propre) a bit too readily. And I apply this to their other pieces in this show – the paper which moves (conveyor belt?) beneath hands holding both a pencil and then an electric eraser makes me want to shout “I get it, OK , I get it! I get Rauschenberg, I get updating pieces to the digital era, I get a certain fashionable emptiness…”

The piece in the stairwell, though, is a different kettle of fish. Entitled ‘Fan/Paper/Fan’ it does what it says on the tin. A pair of hands places a piece of paper between two fans blowing towards each other in such a manner that the paper temporarily defies gravity and stands on its edge on its shorter side. Well, not so much stands as staggers like a gleeful drunk, manic ballerina or even someone just desperate for a pee. Then it falls and the hands re-position it, and maybe it’s just me (and even if, I offer it to you as an affective pathway to the work) but here, rather than a closing off or a patness, there is a tremendous opening out – the metaphor of the paper’s embodiment resonates with the human figure who intervenes and helps (or tasks) it. It’s difficult to resist anthropomorphising the fans, too, as windheads in map corners or Tweedles Dum & Dee. I’m going to use the artworld kiss of death term “moving” to sum it up.

The second two artists I want to hymn are to be found in the project space. The first is Sam Messenger who makes large scale abstract drawings on dense paper which is subjected to some sort of weathering process – hence, I assume, the mysterious listing of saltwater in the description of one. The net or skein of white pigment which floats upon a dark and varied but subtly modulated wash is applied according to some sort of Fibonacci based algorithm (as per usual with artists and maths the actual detail is elusive). Much play is made of the ceding of control which goes with this, together with the, therefore somewhat surprising, point that this algorithm doesn’t permit a prediction of the drawing’s final state at any point before this is reached. I get it, though, I think – the set of conditions must be firm enough to follow straightforwardly and to yield visually coherent results but at the same time there must be some choices, forks, within the procedure. What this yields is a complex detail nothing short of exquisite. Particularly lovely is the way that the drawings bulge away from the wall and also just how lost in their surfaces one soon finds oneself. It took me a little while to believe that the white “surface” network was not applied in some mechanical way (especially given the prevalence of mechanical /digital assistance/participation in the work of some other artists in the show) but close and detailed examination reveals uncertainties in marking that could come only from a human hand.

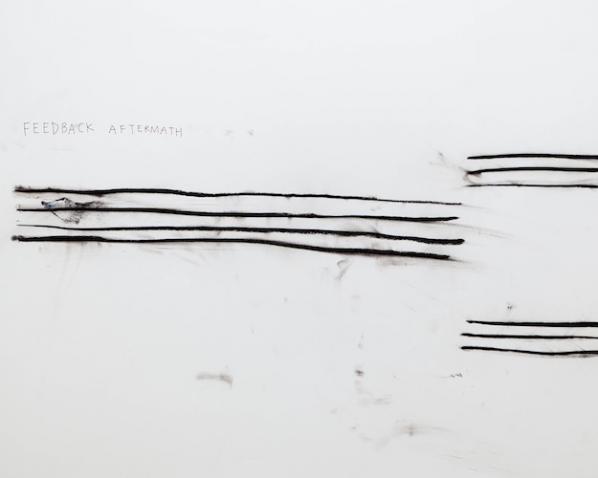

The final piece in this tour of highlights and, on a best till last basis, the one which affected me the most is a single piece by Christine Sun Kim, about whom more after I describe both the work and my first response to it. We see a drawing of a text, of three systems of horizontal lines resembling music manuscript staves (though in each case one or more lines short of the usual five) and smudges. The largest of the smudges and one which suggests it contains some colour – it’s curiously difficult to tell, I think it does – sits athwart the middle system of lines. Elsewhere there are much smaller patches which presumably arise out of a loose way of working with the charcoal of the lines. These lines themselves are gorgeous, varying markedly in width (but remaining lines, not shapes) and performing a similar balancing act with their relation to the horizontal, from which they depart but never enough to threaten our reading of them as such. Above the top left of the system of lines there is a text in clear and deliberate but slightly spidery sober brown capitals which reads FEEDBACK AFTERMATH. “Sounds like the name of a heavy metal band,” I remarked to my companion, who laughed gamely. But there is something bold and mysterious about it. After the band name, motivated in part by the horizontality of staves, their wavering might conjure a seismographic recording, or simply (and especially in the context of this show) some kind of algorithm at work. All this far from exhausts the visual pleasures of the piece. The central positioning of the marks, the feeling of a space divided into mark and void but at the same time a void graduated from nothingness up through a series of increasingly visible smudges. The palpable sense of the performative in a drawing like this. Oh it’s great! I wish you could see it! You can! (until Sept 13th 2014) Go.

On reading the handout we discover that

Christine Sun Kim, who has been deaf since birth, explores the materiality of sound in work that connects sound to drawing, painting, and performance. Her performances are often the starting point for works on paper that display witty evocations of powerful sounds or loaded silences.

I quote it not to flaunt my perceptiveness but to observe how vigorous and alive the work is even without contextualizing info. It wouldn’t matter a two-penny damn if read the “wrong” way either, it’s the sheer power, variety and beauty of the mark-making and its appeal across a whole range of things from cultural codes such as music and language, through graphs and charts through to the facts of our embodiment – our perception of dark and light, our manual dexterity or surrender to chance, the need to play, the right to say ‘fuck it!’ and leave that mark there; to own it.

So what is my beef? Part of it lies in the curatorial notion of “expanded” drawing, a conceptual movable feast. It implies some kind of comprehensible set of practices which make drawing –what? –more expressive, more up to date, capable of things that were previously not possible… I don’t know, neither do you and neither does anyone. At its most straightforward one could read it as works made which are somehow adjacent in some way to drawing –so a number of works involve moving image works of drawings or the act of drawing. But hold on –there’s a perfectly respectable word for this which is animation or, if this is stretching it, moving image work with drawing as its topic. I would be reluctant to call these works themselves drawings, expanded or no, with the exception of Fan/Paper/Fan where a path is drawn by the jittering paper. Likewise much play is made of the uses over the last forty years of mechanical means of ..er..drawing. Except one feels the weight of history and usage would fall more appropriately behind the simple print.

It probably wouldn’t be worth losing any sleep over it all except this comes to a head for me in two large scale works, one at each site. The first is a piece by Raphael Lozano Hemmer whose

Seismoscope device detects vibration around it, from footsteps to tectonic shifts, and records this vibration on paper using an automated XYplotter. As the Seismoscope registers a seismic wave, it is programmed to draw an illustration of a single 11th Century Sceptical philosopher, over and over again. The actual traces of the drawing follow a random path, while staying within the portrait image that has been burned into the memory of the device, thus each drawing emerges unique.

And each of these drawings to date is pinned up on the adjacent wall on a daily basis (although in a move that doesn’t exactly bespeak confidence a “completed” version is retained in the “out” hopper of Lozano Hemmer’s machine so that we can see what it’s like.) What one sees on the wall is a series of drawings which appear to have stopped at various points in the process of being plotted out. It looks as though something about the software tends to create a blotch of ink at that stopping point. Otherwise the images are hard to distinguish. The descriptive text is evasive about how the tremor detection feeds into the plotting process. Does an initial tremor start it or is it merely that the tremors alter the manner of laying on pigment within the template that is already programmed into the installation so the lines go on in different ways within the bounds laid down? The words sledgehammer and nut occur when such a fetishisation of the digital and mechanical is applied to results which are..well… kind of OK-ish but contain, even conceptually (lest I’m accused of being unduly optical) little to move or amaze.

There’s a similar mountain labouring to bring forth mouse situation with Julius von Bismarck & Benjamin Maus’s (ha! Just noticed!) Perpetual Storytelling Apparatus which, in truth, is a beautiful thing to behold –a wall mounted plotter which spews forth a seemingly endless scroll of printed paper, populated, the notes tell us with that hubristic gigantism that so often afflicts such documents, by drawings from “seven million patents – linked by over 22 million references”. The mechanism is easily explained (and perhaps this itself is significant). There is a root text (for one showing it was, apparently, Alice in Wonderland) and by the miracle of software and data equivalence the text is translated into a set of illustrations comprising drawings drawn from the previously mentioned patent database which are then printed out onto the scroll of paper. The artists don’t reveal the source text until after the close of the show. As noted, it’s a handsome process to watch and the drawings have the strange surreal beauty of the technical drawing uprooted from its context but there is an implicit claim made by the artists with their title (supported explicity by the curatorial “New visual connections and narrative layers emerge within the telling of this story through the graphical depiction of technical advancements”) that something resembling a narrative emerges from all this hoo-ha. To put it bluntly – it so does not. You would have to strain your imaginative faculties enormously and do some heavy duty cultural forgetting to even begin to find narrative here, because the images on which the thing piggybacks are so distinctive, strange and beautiful in and of themselves. It’s instructive to compare this rather polished and curator friendly but ultimately disappointing piece with the wonderful and messy anarchy of its distant ancestor, MTAA’s Endnode (aka Printer Tree) of 2002 where a cheap and cheerful plywood tree with printers in its branches dispensed prints of posts to a created-for-the-occasion e mail list. (Images: http://www.endnode.net/install.html background: http://www.endnode.net/index.html)

So I want to finish by saying, once again, this is a great show. There’s a lot of good stuff I haven’t even mentioned, some of Evan Roth’s work in particular. But its basis bothers me a lot – I’m certainly very far from wanting to exclude the digital, the mechanical and the procedural from an as yet to be really seriously defined expanded drawing practice but at the moment it is still drawing’s appeal to and demands on the artist’s embodiment and our embodied imagination that give rise to by far the most engaging work here.

Pencil / Line / Eraser

At Carroll/Fletcher

1 August – 13 September 2014

Jonas Lund’s artistic practice revolves around the mechanisms that constitute contemporary art production, its market and the established ‘art worlds’. Using a wide variety of media, combining software-based works with performance, installation, video, photography and sculptures, he produces works that have an underlying foundation in writing code. By approaching art world systems from a programmatic point of view, the work engages through a criticality largely informed by algorithms and ‘big data’.

It’s been just over a year since Lund began his projects that attempt to redefine the commercial art world, because according to him, ‘the art market is, compared to other markets, largely unregulated, the sales are at the whim of collectors and the price points follows an odd combination of demand, supply and peer inspired hype’. Starting with The Paintshop.biz (2012) that showed the effects of collaborative efforts and ranking algorithms, the projects moved closer and closer to reveal the mechanisms that constitute contemporary art production, its market and the creation of an established ‘art world’. Its current peak was the solo exhibition The Fear Of Missing Out, presented at MAMA in Rotterdam.

Annet Dekker: The Fear Of Missing Out (FOMO) proposes that it is possible to be one step ahead of the art world by using well-crafted algorithms and computational logic. Can you explain how this works?

Jonas Lund The underlying motivation for the work is treating art worlds as networked based systems. The exhibition The Fear Of Missing Out spawned from my previous work The Top 100 Highest Ranked Curators In The World, for which I assembled a comprehensive database on the bigger parts of the art world using sources such as Artfacts, Mutaul Art, Artsy and e-flux. The database consists of artists, curators, exhibitions, galleries, institutions, art works and auction results. At the moment it has over four million rows of information. With this amount of information – ‘big data’ – the database has the potential to reveal the hidden and unfamiliar behaviour of the art world by exploring the art world as any other network of connected nodes, as a systemic solution to problematics of abstraction.

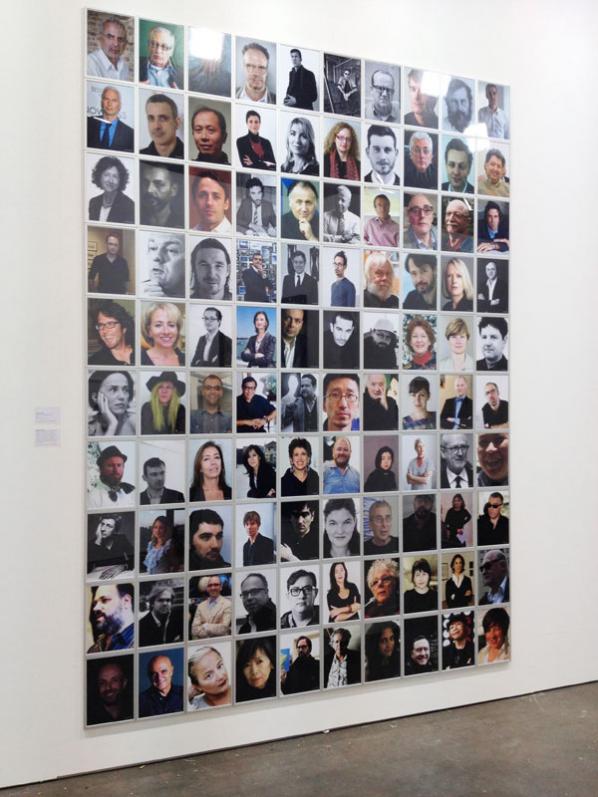

In The Top 100 Highest Ranked Curators In The World, first exhibited at Tent in Rotterdam, I wrote a curatorial ranking algorithm and used the database, to examine the underlying stratified network of artists and curators within art institutions and exhibition making: the algorithm determined who were among the most important and influential players in the art world. Presented as a photographic series of portraits, the work functions both as a summary of the increasingly important role of the curator in exhibition making, as an introduction to the larger art world database and as a guide for young up and coming artists for who to look out for at the openings.

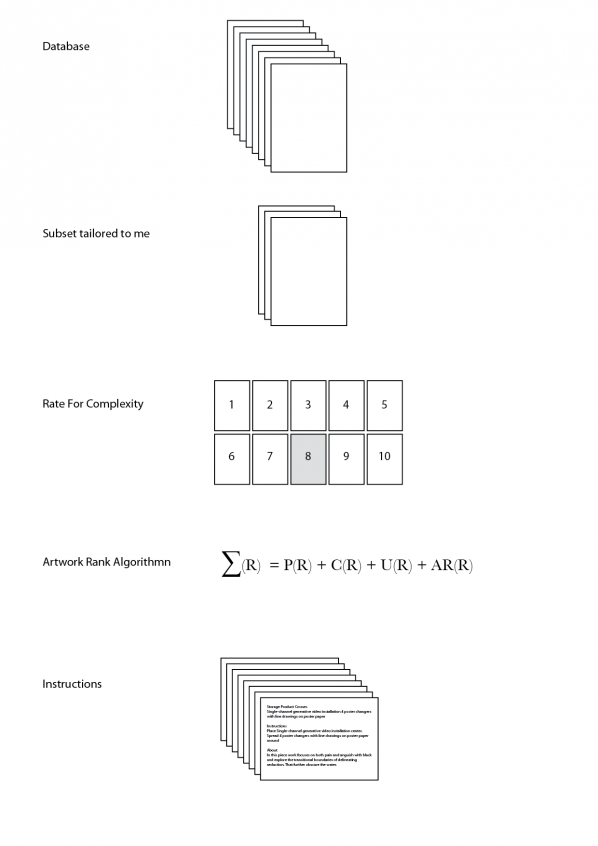

Central to the art world network of different players lies arts production, this is where FOMO comes is. In FOMO, I used the same database as the basis for an algorithm that generated instructions for producing the most optimal artworks for the size of the Showroom MAMA exhibition space in Rotterdam while taking into account the allotted production budget. Prints, sculptures, installations and photographs were all produced at the whim of the given instructions. The algorithm used meta- data from over one hundred thousand art works and ranked them based on complexity. A subset of these art works were then used, based on the premise that a successful work of art has a high price, high aesthetic value but low production cost and complexity, to create instructions deciding title, material, dimensions, price, colour palette and position within the exhibition space.

Similar to how we’re becoming puppets to the big data social media companies, so I became a slave of the instructions and executed them without hesitation. FOMO proposes that it is possible to be one step ahead of the art world by using well-crafted algorithms and computational logic and questions notions of authenticity and authorship.

AD: To briefly go into one of the works, in an interview you mention Shield Whitechapel Isn’t Scoop – a rope stretched vertically from ceiling to floor and printed with red and yellow ink – as a ‘really great piece’, can you elaborate a little bit? Why is this to you a great piece, which, according to your statement in the same interview, you would not have made if it weren’t the outcome of your analysis?

JL: Coming from a ‘net art’ background, most of the previous works I have made can be simplified and summarised in a couple of sentences in how they work and operate. Obviously this doesn’t exclude further conversation or discourse, but I feel that there is a specificity of working and making with code that is pretty far from let’s say, abstract paintings. Since the execution of each piece is based on the instructions generated by the algorithm the results can be very surprising.

The rope piece to me was striking because as soon as I saw it in finished form, I was attracted to it, but I couldn’t directly explain why. Rather than just being a cold-hearted production assistant performing the instructions, the rope piece offered a surprise aha moment, where once it was finished I could see an array of possibilities and interpretations for the piece. Was the aha moment because of its aesthetic value or rather for the symbolism of climbing the rope higher, as a sort of contemporary art response to ‘We Started From The Bottom Now We’re Here’. My surprise and affection for the piece functions as a counterweight to the notion of objective cold big data. Sometimes you just have to trust the instructionally inspired artistic instinct and roll with it, so I guess in that way maybe now it is not that different from let’s say, abstract painting.

AD: I can imagine quite a few people would be interested in using this type of predictive computation. But since you’re basing yourself on existing data in what way does it predict the future, is it not more a confirmation of the present?

JL: One of the only ways we have in order to make predictions is by looking at the past. Through detecting certain patterns and movements it is possible to glean what will happen next. Very simplified, say that artist A was part of exhibition A at institution A working with curator A in 2012 and then in 2014 part of exhibition B at institution B working with curator A. Then say that artist B participates in exhibition B in 2013 working with curator A at institution A, based on this simplified pattern analysis, artist B would participate in exhibition C at institution B working with curator A. Simple right?

AD: In the press release it states that you worked closely with Showroom MAMA’s curator Gerben Willers. How did that relation give shape or influenced the outcome? And in what way has he, as a curator, influenced the project?

JL: We first started having a conversation about doing a show in the Summer of 2012, and for the following year we met up a couple of times and discussed what would be an interesting and fitting show for MAMA. In the beginning of 2013 I started working with art world databases, Gerben and I were making our own top lists and speculative exhibitions for the future. Indirectly, the conversations led to the FOMO exhibition. During the two production phases, Gerben and his team were immensely helpful in executing the instructions.

AD: Notion of authorship and originality have been contested over the years, and within digital and networked – especially open source – practices they underwent a real transformation in which it has been argued that authorship and originality still exist but are differently defined. How do see authorship and originality in relation to your work, i.e. where do they reside; is it the writing of the code, the translation of the results, the making and exhibiting of the works, or the documentation of them?

JL: I think it depends on what work we are discussing, but in relation to FOMO I see the whole piece, from start to finish as the residing place of the work. It is not the first time someone makes works based on instructions, for example Sol LeWitt, nor the first time someone uses optimisation ideas or ‘most cliché’ art works as a subject. However, this might be first time someone has done it in the way I did with FOMO, so the whole package becomes the piece. The database, the algorithm, the instructions, the execution, the production and the documentation and the presentation of the ideas. That is not to say I claim any type of ownership or copyright of these ideas or approaches, but maybe I should.

AD: Perhaps I can also rephrase my earlier question regarding the role of the curator: in what way do you think the ‘physical’ curator or artist influences the kind of artworks that come out? In other words, earlier instructions based artworks, like indeed Sol LeWitt’s artworks, were very calculated, there was little left to the imagination of the next ‘executor’. Looking into the future, what would be a remake of FOMO: would someone execute again the algorithms or try to remake the objects that you created (from the algorithm)?

JL: In the case with FOMO the instructions are not specific but rather points out materials, and how to roughly put it together by position and dimensions, so most of the work is left up to the executor of said instructions. It would not make any sense to re-use these instructions as they were specifically tailored towards me exhibiting at Showroom MAMA in September/October 2013, so in contrast to LeWitt’s instructions, what is left and can travel on, besides the executions, is the way the instructions were constructed by the algorithm.

AD: Your project could easily be discarded as confirming instead of critiquing the established art world – this is reinforced since you recently attached yourself to a commercial gallery. In what way is a political statement important to you, or not? And how is that (or not) manifested most prominently?

JL: I don’t think the critique of the art world is necessarily coming from me. It seems like that is how what I’m doing is naturally interpreted. I’m showing correlations between materials and people, I’ve never made any statement about why those correlations exist or judging the fact that those correlations exist at all. I recently tweeted, ‘There are three types of lies: lies, damned lies and Big Data’, anachronistically paraphrasing Mark Twain’s distrust for the establishment and the reliance on numbers for making informed decisions (my addition to his quote). Big data, algorithms, quantification, optimisation… It is one way of looking at things and people; right now it seems to be the dominant way people want to look at the world. When you see that something deemed so mysterious as the art world or art in general has some type of structural logic or pattern behind it, any critical person would wonder about the causality of that structure, I guess that is why it is naturally interpreted as an institutional critique. So, by exploring the art world, the market and art production through the lens of algorithms and big data I aim to question the way we operate within these systems and what effects and affects this has on art, and perhaps even propose a better system.

AD: How did people react to the project? What (if any) reactions did you receive from the traditional artworld on the project?

JL: Most interesting reactions usually take place on the comment sections of a couple of websites that published the piece, in particular Huffington Post’s article ‘Controversial New Project Uses Algorithm To Predict Art’. Some of my favourite responses are:

‘i guess my tax dollars are going to pay this persons living wages?’

‘Pure B.S. ……..when everything is art then there is no art’

‘As an artist – I have no words for this.’

‘Sounds like a great way to sacrifice your integrity.’

‘Wanna bet this genius is under 30 and has never heard of algorithmic composition or applying stochastic techniques to art production?’

‘Or, for a fun change of pace, you could try doing something because you have a real talent for it, on your own.’

AD: Even though the project is very computational driven, as you explain the human aspects is just as important. A relation to performance art seems obvious, something that is also present in some of your other works most notably Selfsurfing (2012) where people over a 24 hour period could watch you browsing the World Wide Web, and Public Access Me (2013), an extension of Selfsurfing where people when logged in could see all your online ‘traffic’. A project that recalls earlier projects like Eva & Franco Mattes’ Life Sharing (2000). In what way does your project add to this and/or other examples from the past?

JL: Web technology changes rapidly and what is possible today wasn’t possible last year and while most art forms are rather static and change slowly, net art in particular has a context that’s changing on a weekly basis, whether there is a new service popping up changing how we communicate with each other or a revaluation that the NSA or GCHQ has been listening in on even more facets of our personal lives. As the web changes, we change how we relate to it and operate within it. Public Access Me and Selfsufing are looking at a very specific place within our browsing behaviour and breaks out of the predefined format that has been made up for us.

There are many works within this category of privacy sharing, from Kyle McDonalds’ live tweeter, to Johannes P Osterhoff’s iPhone Live and Eva & Franco Mattes’ earlier work as you mentioned. While I cannot speak for the others, I interpret it as an exploration of a similar idea where you open up a private part of your daily routine to re-evaluate what is private, what privacy means, how we are effected by surrendering it and maybe even simultaneously trying to retain or maintain some sense of intimacy. Post-Snowden, I think this is something we will see a lot more of in various forms.

AD: Is your new piece Disassociated Press, following the 1970s algorithm that generated text based on existing texts, a next step in this process? Why is this specific algorithm of the 70s important now?

JL: Central to the art world lies e-flux, the hugely popular art newsletter where a post can cost up to one thousand dollars. While spending your institution’s money you better sound really smart and using a highly complicated language helps. Through the course of thousands of press releases, exhibition descriptions, artist proposals and curatorial statements a typical art language has emerged. This language functions as a way to keep outsiders out, but also as a justification for everything that is art.

Disassociated Press is partly using the Dissociated Press algorithm developed in 1972, first associated with the Emacs implementation. By choosing a n-gram of predefined length and consequently looking for occurrences of these words within the n-gram in a body of text, new text is generated that at first sight seems to belong together but doesn’t really convey a message beyond its own creation. It is a summary of the current situation of press releases in the international English art language perhaps, as a press release in its purest form. So, Disassociated Press creates new press releases to highlight the absurdity in how we talk and write about art. If a scrambled press release sounds just like normal art talk then clearly something is wrong, right?