“Flexicity, information city, intelligent city, knowledge-based city, MESH city, telecity, teletopia, ubiquitous city, wired city… [what is] a city that dreams of itself?” (Jones 2016).

This April, 28 brave souls came together for the first time to explore algorithmic ghosts in Brighton — a city known for its blending of new-age spiritualities and digital medias, but perhaps not yet for its ghosts — through the launch of a new psychogeography tour for the Haunted Random Forest festival. Unveiling machine entities hidden within seemingly idyllic urban landscapes, from peregrine falcon webcams to always-listening WiFi hotspots, we witnessed a new glimpse of an old city, one that afforded many strange moments of unexpected (and perhaps even radical!) wisdom regarding the forgotten structures, algorithms and networks that traverse Brighton daily alongside its human inhabitants.

This intervention found its greatest inspiration in the playful, crtitical, anti-authoritarian strategies of the Situationist International group that was prominent in 1950s Europe and birthed the fluid concept of dérive or “drift”, a new method for engaging with cities like Paris through “psychogeographic” walks that charted increasingly inconsistent evolutions of urban environments and their effects on individuals. “Perhaps the most prominent characteristic of psychogeography is the activity of walking,” explains Sherif El-Azma from the Cairo Psychogeographical Society. “The act of walking is an urban affair, and in cities that are increasingly hostile to pedestrians, walking [itself]… become[s] a subversive act.”

Psychogeographical drifts have been interpreted in many ways in many places, from radical city tours with no set destination, to public pamphlets meant to shock people out of their daily urban routines, to unsanctioned street artworks that explore changing architectures and hegemonies of the built environment through direct dialogues. As the Loiterer’s Resistance Movement explains, “We can’t agree on what psychogeography means, but we all like plants growing out of the sides of buildings, looking at things from new angles, radical history, drinking tea and getting lost, having fun and feeling like a tourist in your home town. Gentrification, advertising, surveillance and blandness make us sad… our city is made for more than shopping. We want to reclaim it for play and revolutionary fun.”

In our own interpretation of the psychogeography “play box“, people from across the UK came together from local community discussion lists, universities and creative networks to join the group. We called them ‘node guardians’ to connote a shared sense of ownership regarding both the tour nodes (which were lead not only by ourselves but also by several other brave participants, who also facilitated hands-on activities to engage listeners more deeply in the lived experiences of each machine node). We were intrigued about the moments of access, control and liberation that might be exposed when the machines, networks and algorithms that we engage with on a daily basis were revealed. In the unearthing of lesser-known instances of code-based activity (and the patterns within), we hoped to meet machine spirits, languages and loves along the way. And meet them we did.

Although the tour aimed to seek out algorithms and machines, we didn’t feel limited to influences from our current digital age. Brighton has a rich history of invention and engineering which has influenced the local geography as well as wider culture. The ghosts of Magnus and George Herbert Volk, father-and-son engineers, can be found all over the city, from Magnus Volk’s seafront Electric Railway which opened in 1883 — making it the oldest working electric railway in the world — to George’s seaplane workshop in the trendy North Laine shopping area, which went on to house a thoroughly modern digital training provider, Silicon Beach Training. Magnus Volk’s most unusual invention, though, only exists as a part of Brighton’s colourful history: the Brighton and Rottingdean Electric Railway, as it was officially called, earned the nickname the ‘daddy-long-legs railway’ as it ran right through the sea with the train car raised up above the waves on 7-meter-long legs. The railway was only in operation for 5 years from 1896 to 1901, but you can still see some of the railway sleepers for the tracks along the beach at low tide.

For a relatively small town, Brighton also played a surprisingly big role in the development of the international cinema industry. In the 1890s and 1900s, a group of early filmmakers, chemists and engineers called the Brighton School pioneered film-making techniques such as dissolves, close-ups and double exposure, and created new processes for capturing and projecting moving images. Key members of the group used the old pump house in local pleasure garden St Ann’s Wells as a film laboratory and shot the world’s first colour motion picture called ‘A Visit to the Seaside’ in Brighton in 1908, using a colour film process called Kinemacolour invented by the group. Although the city’s early passion for cinema is remembered by several blue plaques marking key locations — and the presence of the Duke of York’s cinema, the oldest continually operating cinema in the UK — we wondered how much of Brighton life had been captured in the dozens of short films made at the turn of the century, only to be lost forever?

The rest of the stops on our walking tour took in more contemporary machine ghosts, including the last remaining trace of the city’s USB dead drop network — conveniently embedded in a brick wall on the seafront above the Fishing Museum — which prompted us to ask what information people may have passed to each other before these devices were destroyed by weather and vandals. Dead drops were originally set up to be an anonymized form of peer-to-peer file-sharing that anyone could use in public spaces. They have since been embedded into buildings, walls, fences and curbs across the world. Perhaps some of our tour participants will even be inspired to set up new dead drops around the city to keep the potential for off-grid knowledge-sharing alive.

In a reversal of this spirit of anonymous digital communication, a new network of WiFi-enabled lampposts, CCTV cameras and other pieces of ‘street furniture’ has been unobtrusively installed across the city by BT, in partnership with Brighton & Hove City Council. They now eavesdrop on the personal musings of passers-by who connect to them. These hidden devices provide users with a free WiFi service, but the group wondered at what cost. Participants found themselves questioning whether BT can be trusted to keep our information secure in an age where data has become a valuable marketing commodity.

As part of our psychogeographical aim to unveil the hidden lives of once-familiar urban artefacts, we also summoned the machine ghosts of some of Brighton’s most famous (and infamous) landmarks. Looming over the city centre is a towering modernist high-rise called Sussex Heights, a building that sticks out like a sore thumb amidst the classic Regency architecture of the city’s Old Town. Yet atop the concrete tower also live families of peregrine falcons, whose nesting activities are broadcast to the world by an ever-watching webcam. Conservation groups, architects and technologies intersected in 1990 to provide a nesting box that would enable the falcons, extinct in the area at the time, to successfully breed. They now return to the tower block every spring to rear their young (except in 2002, when they chose the West Pier instead). Writing down our best wishes to this season’s hatchlings, we pasted them onto the building for future city ghosts to browse.

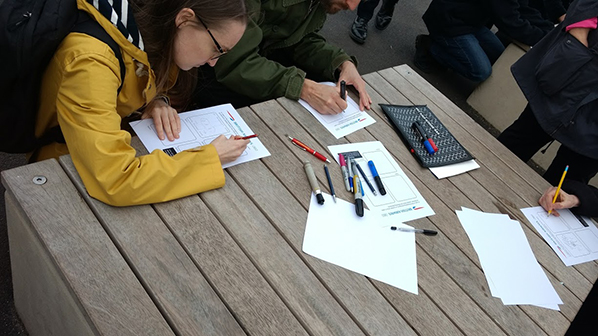

The other most visible instance of architectural and structural technologies descending upon the city can be seen in the new British Airways i360 viewing tower, variously described as a ‘suppressed lollipop’, a ‘hanging chad’, ‘an oversized flagpole’, an ‘eyesore’ and a ‘corporate branding post’. Even if you leave the city, you can’t get away from the sight of the 162-metre tall tower, as it is equally visible from the countrysides surrounding Brighton. It overshadows its neighbour, the beloved remains of the burnt-out West Pier, and opened exactly 150 years after the West Pier first opened in 1866. However, the ‘innovation’ in the i360’s name may be a boon to the city, as it’s expected to pour £1 million a year in the local community and potentially inspire the renovation of the West Pier. Our node-guardians bravely attempted a participatory activity outside the i360 which involved sketching out mock flight warnings to those who entered its gates; the mock flight attendants situated at the base of the i360 were less than amused by these efforts.

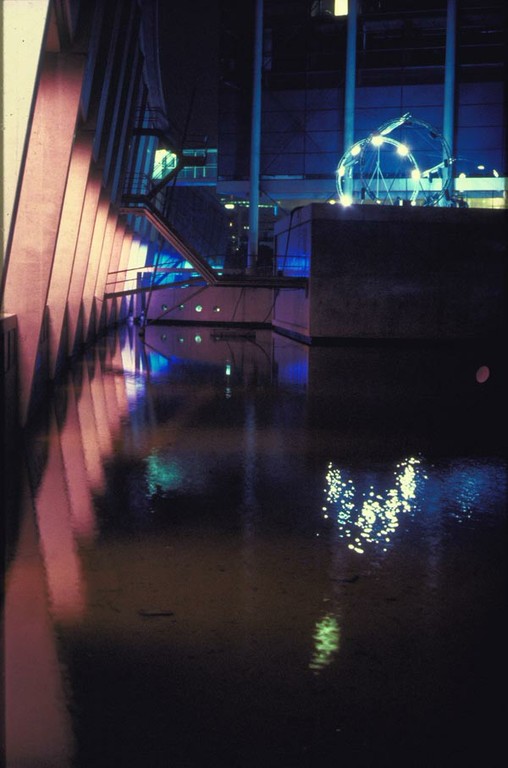

In most towns, the shopping centre becomes a well-known haunt for both locals and visitors to congregate, yet most people who visit Brighton’s Churchill Square shopping mall pass by the square’s large pair of digital sound sculptures without even a glance. The sculptures look like a pair of matching stone and bronze spheres, and are the type of public art that you can walk past everyday without actually looking at, but after looking into their always-observing faces once, you’ll never miss them again. They quietly interact with the sky every day through a set of complicated light sensors that trigger a series of musical notes tuned in to each orchestration and angle of the sun. As the sun rises, they call out to one another, their combined song fading away as the sky turns dark. Or at least, we are told they communicate; after a group activity to emulate the interactivities of the spheres, we found ourselves quite unsure if we had actually heard ghostly spherical music emanating from spherical mouths, or just the sound of shoppers and buses passing by.

And finally, if you’ve lived in Brighton for a while you’ve probably come across the French radio station FIP, which until a few years ago you could tune into on radios across the city. While standing in the bustling North Laine cultural quarter, we were briefly transported to Paris by one of our node guardians’ melodica renditions of Parisian cafe music, and heard the story of how a local resident introduced Brighton to FIP in the late 1990s when they started re-broadcasting the radio station out over the city. It became one of the most popular radio stations in town and transmissions continued until 2013, even surviving an Ofcom raid on the mystery broadcaster’s house in 2007 when their equipment was confiscated. The story of Brighton’s love for FIP radio, including a monthly fan-organised club night called Vive La FIP that joyously ran from clubs around the city for years, shows that as well as its own ghosts, our city is also haunted by the machines of distant places.

Indeed, from the distant ghosts of rebellions past to those who quietly slip by underfoot as we walk to the pier, the derives of this tour taught us that unearthing hidden histories of a city can bring both good and bad spirits back to life — moments of local liberation and defiance existing alongside a national state of increased surveillance, conglomeration and control. We call for future tours, psychogeographic and otherwise, that challenge participants to think about Brighton through new forms of engagement that focus on grassroots and community efforts, and their implications in the spaces and places we use every day. Only then can we determine whether the ghosts that surround us are in charge of our fates, or whether the myriad past and present struggles of this city can co-exist in collaboration.

The exhibition Power and Architecture was created for viewing across several months in a particular sequence. Part 1 focused on Utopia and Modernity (12 June – 3 July), Part 2 on Dead spaces and Ruins, (July 4 – August 10), Part 3 on Citizen activated space — Museum of Skateboarding,(11 August – 11 September), and Part 4 on The afterlives of Modernity — shared values and routines, (15 September – 9 October). A conference held in June – The Centre Cannot Hold? –led by important scholars Michał Murawski (SSEES, UCL) and Jonathan Bach (New School, New York) served to frame the cultural, political, economic ramifications of “centrality and monumentality in 20th century cities” with thought from prominent researchers, architects and artists. Power and Architecture concluded this October as the Calvert 22 Foundation partners with innovative architecture, design and engineering collectives Assemble (UK), Museum of Architecture (UK) and reSITE (CZ) and an Urban Research Mobility Lab connects London with Prague by asking the question: how does migration and mobility in cities affect the experience of the urban environment? A curated series of reports, essays and photo stories further explored the themes of Power and Architecture in the online Calvert Journal available through the gallery website.

Calvert 22 is a gallery devoted to contemporary Eastern European and Russian art. They presented this exhibition as “a season on utopian public space and the quest for new national identities across the post-Soviet world.” I arrived at the gallery, a Californian artist, coincidentally just as I’d read comments from Lev Manovich about the young intelligensia of post-Soviet Russia. Thus, when thinking about the exhibition, I was also thinking about the new global mobile class and the impact of Putin’s Russia upon a new generation.

Power and Architecture is a fascinating collection of research into contemporary art, films, and research about post-Soviet urban identity and the positioning of artists therein. Obviously once communist societies have experienced dramatic change since the fall of the Berlin Wall, collapse of Soviet Russia, and rise of Putin to power. Curators used multiple cultural lenses with which to pry open a critical “western” eye on the aftermath of the Soviet era and invited exploration of cultural narratives about the “post-Soviet” city. The exhibit, particularly in certain places, looked at ideas which appear to have disappeared or become outmoded as a means of aesthetic and political communication. There was an air of longing and self-reflection towards Russian identity when experiencing the work. The Russian people have something to reckon with; a revolutionary utopia which once was, but which is no more and which has left them with the traces of an almost empire,- although to call communist Russian an empire seems to obscure the politics of the revolutionary element-. These juxtapositions were in essence the heart of the show which explored the Soviet Union as constructed space. This ”location” then functions as a backdrop to present-day national identity and urban design emerges in the portrait of a “post-Soviet” society with its own futuristic ideas as well as in the lingering relics of Soviet intentions.

Power and Architecture falls on the heels of Calvert 22’s very successful Red Africa program which examined the cultural, economic and social geography between Africa, Eastern Europe, Russia and related countries during the Cold War. The Eastern European art historical and social trend of the last thirty years labelled ‘self-historicization’ –or the self-conscious effort for Eastern European and Russian artists to articulate, archive, and collect their own history, is exercised throughout the exhibit itself designed in series of presentations directed at the problem of “historical understanding” of history. The post-Soviet city and utopian public space was used as a critical framework from which to position contemporary space, identity and the intent of the exhibiting artists. The Soviet Union has fallen, but who or how is its revising and re-examination taking place?

Part 2 which dealt with “dead spaces”, the architectural ruins of empty cities, military bases, technologial infrastructure and cavernous, open landscapes at once modern and moribund seemed to suggest that retrospective analysis of utopia could only be a well-conceived guess at what was or might have been. This Part was a sojourn into the life of Soviet artifacts both remaindered in their historical trajectory and as a convincing backdrop to a pervasive contemporary ambivalence. Danila Tkachenko’s “Restricted Areas” for instance, was a series of photographs documenting relics of the military build up of the Soviet Union only to be found on abandoned, snow-covered sites in the frozen tundra. Oversized photographs of personal ID cards from unknown persons presumably found amidst Soviet architectural rubble, large format, richly-detailed color photographs of crumbling rooms, weather-worn, orphaned Soviet-era paintings, and peeling, once colorful murals inside Soviet military bases and institutions form an historic record of obvious and shocking lack of preservation of Soviet art and architecture as Russian history. Artists participating in Dead spaces and ruins were Vahram Aghasyan, Anton Ginzburg, and Eric Lusito.

To say that this work engaged narratives which imbue modern mythologies of “utopia” with certain ideas, or contained evidence of the self-conscious effort to bring post-Soviet identity into the picture is an understatement. ‘Utopian’ ideas’ exhibited, situated in urbanism and public space, were the self-conscious investigation of old or familiar‘ or “statist” (maybe) viewpoints on public identity and gave curious attention to questions of truth, experience, voice and historic preservation found in documentary discourse. Self-historicization was apparent in Russian artist Kirill Savchenkov’s Museum of Skateboarding, a mixed media installation, which was its own entire Part 3. Savchenkov’s piece talked about the activation of public space by young people and about skateboarding as a means through which to reflect upon the post-Soviet residential suburbs of Moscow. This work suggests how certain architectural interventions or objects contain meaning and can even be accessed differently or more significantly through subculture. It alluded to tropes in notions of “world” or global “utopia” which translate across seemingly disparate spaces and identities such as Californian and post-Soviet/Soviet Russia. Moreover, this reading of public space as accessed and interpreted by youth is a powerful concept about notions of history and who it belongs to.

In Part 4 (on through Oct. 9) the urban poetics of the post-Soviet city are further contextualized by looking more closely at modernity and everyday life. The afterlives of Modernity — shared values and routines. This Part concluded the exhibit with four artists, Aikaterini Gegisian, Donald Weber, Dmytrij Wulffius, and Ogino Knauss, who examine the “afterlife” of the utopian endeavor, especially the search for new national identity. This theme is provocative to be sure, given the current political contest in the Ukraine and Russia’s role in Syrian conflicts. The curators write:

“Across the former Soviet Union there are a series of architectural and physical nostalgias connecting citizens who share the same socialist history – Part 4 of the programme reflects on these shared values and routines for citizens today.”

I asked myself the question—how does art tie societies together through processes of change? Aikaterini Gegesian’s film, “My Pink City” offers a portrait of a post-Soviet Yeravan in transition and depicts the militarisation of public space and the gendered divisions within the city. In many instances, Russian government has pushed for laws “designed to rid Ukraine’s public spaces of communist relics. Their destruction proclaims a deep desire to change the cultural narrative.” In Part 2 many documentary photographs of “dead” Soviet relics are a poignant record, and politically at odds with ideas at play in contemporary Russian national consciousness. It is a record which rightfully belongs to the Russian and Ukrainian people and which makes this show more meaningful when thought of as the struggle to preserve the past for the future.“Monumental Propaganda”, a series by Donald Weber documenting sites where Soviet monuments stood and the empty pedestals remain, speaks to exactly this. Dmytrij Wulffius’ “Traces on Concrete” is a series of photographs taken from 2009 and 2013 of his own hometown, Yalta in Crimea, which also explore its architectural landscape from the perspective of modern youth. “Re:centering Periphery: Post Socialist Triplicities” by Ogino Knauss is a fascinating examination of post-socialist history in Berlin, Belgrade, and Moscow, three cities in which modernity triggered profound utopianism towards the “radical transformation of the everyday.” The piece looks at “what is left of the architectural vision in the cities and what this legacy leaves to citizens”.

Power and Architecture aimed at a present-day coming to terms with a particular Russian existence now broken into segments and pieces. It focused profoundly on the precarity and erasure of history which plagues 21st century thought on so many levels.The real and the fake, the true and false, the meanings of “Soviet utopian vision” and its presence in time in architectural and artistic form. Without quite melding together as what that vision was in the political sense, the show formed a quasi-science fictional narrative and interpretation; a history of place, both real and imagined; promised and denied.

Central to the visual collection and comprehension of these ideas was, curiously, the strategy of the archive where the act of collection takes place and where the borders and edges of history are possible. By focusing upon the urban environment of the Soviet Union now past, Power and Architecture asked us to consider ‘what modernity is” in this context. If it is machine aesthetics as James Bridle (2011) suggests, then which machines have contributed and how do we use this modern aesthetic position on technology to examine a past? If it is the new aesthetic to be looking at old relics with a different lens, then what intellectual “spin” is constructed? For whom, how, and for what? Maybe modernity is all of these—a presence of unprecedented scale in terms of cities, and the sky and the water. How do we see this totality now? How did they see it then?

Modernity did come upon Eastern Europe and Russia, arguably in similar and dissimilar ways to how it was absorbed in the west. Power and Architecture re-examined the Soviet epoch, through what artists are seeing and thinking about what has remained. It seemed expressed as a brute emergence of a set of ideas which, because they were collective, revolutionary, technological, shaped and still shape Russian consciousness, but as a past. How the past is preserved or ingested is again a compelling idea on the power-struggles for “history” which take place in modern times. Power and Architecture elucidated key features of this new era of global subjectivity and societal change through creative lenses of the recent past.

Andreas Broeckmann writes on art, machine aesthetics, and digital culture. He is director of Leuphana Arts Program at the university in Lüneburg, and has played key roles at transmediale – festival for art and digital culture, ISEA2010 RUHR, TESLA-Laboratory for Arts and Media, Berlin, and V2_Organisation Rotterdam, Institute for the Unstable Media. Lawrence Bird interviewed him on our current experience of media and civil society. Image: A. Broeckmann, transmediale 2007 (© Jonathan Gröger)

Lawrence Bird: It’s often said that we inhabit the city differently today because of our engagement with media and media technologies. This has been one of your main concerns, and it makes for a very interesting intersection of media theory and public realm theory. Where does this preoccupation come from on your part?

Andreas Broeckmann: I have arrived at these questions not so much from a theoretical or academic perspective, but in response to specific artistic practices that I was interested in. For my own thinking about this area, the works that the artist group Knowbotic Research were working on in the 1990s were seminal. The participative public installation “Anonymous Muttering” (1996), for instance, initiated a radical clash of the physical urban space with the virtual ‘space’ of the internet, interlacing the activities of the participants in a way that created a strange intermediate zone – maybe we could say that it allowed people to place themselves _in_ the medium. In the series of projects that followed under the title “IO-dencies” (1997-99), Knowbotic Research further explored the possibilities of becoming active, of acting in a virtual environment in a manner that was connected to activities and events in the physical space.

I was working quite closely with the group at the time, presenting some of the projects in Rotterdam where I was a curator at the V2_Organisation, co-authoring texts, organising workshops, etc.. This was a great opportunity to think through the issues of the new, hybrid public sphere that was opening up because of the Internet. In order to understand the works, it was necessary to develop a differentiated conception of what it meant to “be public” or to “become public”. The topic returned, for instance in projects I was involved in by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer in Rotterdam, or a publication on Polish video art by the WRO agency, or a major curatorial on a media facade in Berlin, or, for that matter, more recent projects by Knowbotic Research, like “Be Prepared Tiger”, or “MacGhillie”. Personally, I believe that privacy in all its guises – from camouflage and the absence of surveillance to “a room of one’s own” – is one of the great privileges of a modern individual. Contemporary media and communication technologies have transformed the possibilities of being private dramatically, just as the notion of what it means to be public is subject to drastic changes. And artists are articulating these changes which we are all part of, giving us opportunities to reflect on what is going on, and to imagine how things might also develop otherwise. I think that my interest in the relationship between publicness and intimacy is fed both by a personal sense of urgency and and concern, and by the inspiration I get from artists, not to fall into despair.

Lawrence Bird: Fascinating. So would you say that in the direction media are now evolving, there’s actually an increased scope for private “being” — not just in terms of a potential for increased anonymity and independence, but in terms of a richer and more developed individuality? To a greater degree — or perhaps qualitatively different — than was possible in earlier stages of modernity?

Andreas Broeckmann: Unfortunately not… I say that privacy is a privilege exactly because it is becoming such a rare condition these days. The developments that we speak about are, of course, not unidirectional and homogeneous, but very diffused and heterogeneous, and open to quite different interpretations. For many people, a platform like Facebook or Google-Plus is a way of discovering a new form of sociality in which they try out different ways of being public and being private.As for myself, having been brought up with the Critical Theory analyses of the Frankfurt School, I find it difficult not to see these optimistic readings as dangerously naive – it would be a bit like exploring your inner self in the highly regulated and commercial spaces of a shopping mall… I would not go so far as to say that privacy has completely disappered — as though we were now living in a global village of Big Brother containers, or in a vastly extensive version of the Truman Show. But I do think that today we lack a more widespread critical sense of resistance to the regimes of commodification that have taken the place of what were once “privacy” and “social relations”.

Lawrence Bird: You spoke about the concern of “falling into despair”. How general would you say that motivation is? I don’t know if you’ve thought about it this way, but I’m thinking in terms of Occupy, and the other social movements, many of them enabled by media and engaged by artists, which seem to generate new, and some evidence suggests quite lasting, relationships of trust and hope. Many of these seem to come in response to a recent loss of faith in corporations, governments, financial institutions — older social groups that had an important role in old definitions of “public”. I wonder if your comment connects with a widespread yearning for hope, in response to conditions that might well produce despair?

Andreas Broeckmann: I dare not speculate about the longevity of the relationships that have been built by the different branches of the Occupy movement, but I am skeptical about the longevity of anything that is built on specific internet-based media platforms. Facebook, for instance, was launched in 2004, that’s eight years ago, and the German and many other non-English Facebook services are no older than four years. That’s a very short time, and we might want to remember that platforms like Google (*1998), Facebook, Flickr (*2004) or Twitter (*2006) are not part of the natural environment, but recent services offered by profit-oriented companies which, just as well as they may rule the internet world throughout the 21st century, might also get drowned in the swamps of global capitalism (whose regime includes “customer confidence”).

I would refute the assumption, implicit in your question, that many of the people who protested on the squares in Madrid, Cairo, Washington or Athens last year were people who previously had faith in their governments, or the institutions of capitalism. Of course they didn’t, and quite rightly so. What was special about last year was that there is a new, articulate generation of people who would not put up with the situation of stasis, hopelessness and frustration that has paralysed major parts of global societies since 2003 when, in February of that year, millions who took to the streets around the world in protest, were not able to stop the US government and their allies from starting the war on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. The inflection of this event is different in different parts of the world, but I believe that we share that moment. And this is where the protests in the Arab countries, and those in Spain and Greece, hit the squares on a parallel trajectory: In the same year of 2003, the German government started the implementation of what was called the “Agenda 2010”, a project based on the EU’s 2000 Lisbon agreement of economic restructuring, with the aim of making Europe more competitive on the global market. Since then, in Germany we have seen an erosion of the welfare state, drops in income for lower and middle classes and a huge increase in precarious jobs. But some economists also say that the reason for Germany’s relatively healthy economic situation today, compared with, for instance, Greece or Spain, is that these countries failed to reform their debt-pampered economies. Which is why there is a certain reluctance today in Germany to protect privileges for the Greek middle class, privileges which German citizens already had to give up years ago.

above: Tahrir Square on February 11, by Jonathan Rashad (CC-BY-2.0, 2011).

My point is that if we take things into a more extended historical perspective, and if we count our lives not in short Twitter months, we can see how the struggles, the hopes and the despairs of today are part of a broader set of transformations. And we can see that in these transformations there are forces at work which have a huge inertia and which need to be worked on and battled with both patience and long-term strategies. Like any other revolution, and like in the theatres of the Occupy movement, the one in Egypt may have started on Tahrir Square and the mobilisation of people through media-based social networks, but to complete that revolution, a difficult and drawn-out political struggle needs to be fought. Maybe that is the necessary realisation that hit “the movement” this past winter.

Lawrence Bird: And what form might those long-term strategies take? It’s a huge question perhaps, but do you have any ideas about the shape this restructured public sphere might have to take, what forms of governance and participatory democracy for example, to sustain a more permanent change?

Andreas Broeckmann: Personally, I believe that for the foreseeable future many political struggles will continue to happen in the ‘arenas’ of political institutions like governments, parliaments and other election-based structures, in political parties, public administrations, in transnational and inter-governmental decision-making bodies, in trade unions and NGOs. It is a realm that will only partly be affected or influenced by the online world, and even if the emerging public sphere of the Internet and its social media forums implies a huge expansion and diversification of the mass media dominated public sphere of the 20th century, this expanded public sphere will not necessarily have a bigger impact on political processes than the ‘old’ public sphere did. The experience of the ‘movement’ in Egypt today might be analoguous to that of the APO (the extra-parliamentarian opposition of the students movement) in 1960s and 70s West Germany, i.e. realising the necessity of getting involved in existing state institutions (“the long march through the institutions”), which brought members of that generation to power some 25 years later in universities, in parliaments, in national governments. The relevance and standing of the new Egyptian parties is not proven or disproven in the first elections; it is decided when in ten or twenty years from now they may or may not have been able to change the social consensus about democracy, rights, and freedom.

Lawrence Bird: A confession here: I’m an architect, so I always assume, perhaps naively, that a built infrasructure can play a role in these kinds of transformations. In your opinion, might a material intervention be a necessary part of those changes — distinct from, though perhaps in dialogue with, the mediated public realm? What kind of physical (urban) spaces might serve as a counterpoint or moderator to the transience of the Twitter world — and are those spaces any different from the urban spaces we have now?

Andreas Broeckmann: I doubt whether architecture in the narrower understanding of the term will play much more than a symbolical role in these struggles and transformations. Of course, the built environment, especially the way in which public space is configured, plays a significant role in how public life can unfold in cities. And there are political issues to be fought over: for instance, I find it curious how in many of the European cities the authorities allow the construction of one shopping mall after the other, pushing the social and commercial activity of shopping into privatised and highly regulated control spaces, and then those same authorities are surprised when the neighbourhoods in the vicinity of these malls deteriorate because the normal shops are abandoned or have to be closed, making room for trash and money laundering businesses. The resistance against such developments can at times most effectively be fought in local parliaments that, at least in Germany, have to give their consent to such major construction projects. This makes it necessary to join a political party, get elected into the local parliament, sit around in meetings, deal with all sorts of issues of public interest, etc., and be there when the application for the next shopping mall is up for decision…

Of similar relevance is the designing of the digital sphere through software ‘architectures’ – both in terms of individual applications and services, and in terms of the overall technical infrastructure, both hard- and software, and its governance. The critical discussions around the status of ICANN and, more recently, the public protests against law-making initiatives like SOPA and ACTA, have shown that protests can in fact have an impact on such structures. Yet, that impact will remain cosmetic if the public outcry is not followed up by sustained political work through which the drafting of and the decision-making on such laws is factually influenced. This is what lobby groups do, and this is what social movements also have to do, finding whatever possible and suitable political instrument or institution through which to act.

The major arena of constructing and designing the new political sphere will be in law-making, and I believe that the movement needs critical lawyers, historians of economy and charismatic intellectuals more urgently than architects – although, of course, everybody has an important role to play and no-one who wants to contribute should be sent away.

Lawrence Bird: And how about artists — do they have a role in this? To provoke, perhaps? To articulate social and political conditions? Would you say that whatever that role is, it can be part of the sustained transformation you’re talking about — or do they need to step down into a governance role to take part in that (Vaclav Havel being one example).

Andreas Broeckmann: In my understanding of art, there is no particular role that it can, or even “should” play. I would argue that the most important aspect of art for society is its autonomy and the fact that it has no particular responsibility. Art can beautify, it can decorate, it can irritate, it can disturb, it can question, it can affirm, it can simplify or complicate. Such an “open program” of course implies that individual artists or groups, or specific projects, will take a particular political stand, will try to influence a social or political situation — will seek real impact. This is a form of activism that art can borrow from political groups and movements, but it is not the activism that is crucial for the artistic practice, it is the transgressive articulation that artists may achieve in their own dealing with social realities. I want to emphasize that this is my understanding of art, and I fully respect people who think that art can and must be more engaged in social processes in order to be relevant. But again, I think that what art can give us most importantly is what happens in a zone of freedom that is morally, aesthetically and sometimes also politically more risky than anybody who acts in the political arena — save for the mavericks — would want to be.

So the question, “what should artists do,” can in my understanding only ever be answered: “they should do whatever they do.” It must be the best thing that they can do, they have to be precise in their formulations and realisations, they have to be committed, diligent, and daring. It is wonderful if they can, in that way, help proliferate good ideas and push the political situation in a good direction. But by the same token I believe that it is equally wonderful if artists ask questions that are impossible to answer, or pointing out unsolvable ethical dilemmas, or remove the mask of an opponent only to don it themselves.

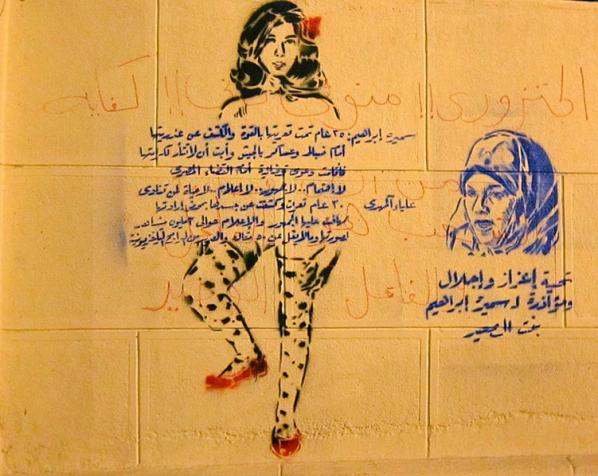

There is, in my eyes, certainly no obligation to go into politics like Havel did. Artists are not always people with a high moral reputation, and stepping into the political arena like Havel did requires stamina and a certain habitus. And there are many ways in which people can intervene in social and political processes. Take the example of Aliaa Magda Elmahdy who posted a photograph of herself naked on her website and sparked a huge debate about the situation of women in the Islamic world. This was not an art project, but it shows what work in the realm of symbols can achieve.

Lawrence Bird: If I could I’d like to steer the conversation in the direction of your thinking on “the wild” — perhaps it relates through the transgressive nature of art you’ve just been discussing, and the tricky relationship of that to civic functions, governance, and related realms of responsibility. Cities have been conceived as set apart from the wilderness — within the city lay the realm of humanity, civility, politics; outside its walls, the wild, monsters, raw life. Girorgio Agamben makes the case that the violence of our times equates to the obliteration of that line: between political life (zoe) and bare life (bios).

In light of what you’ve already said about art and transgression, and the value of that; and the precarious status of privacy today, and the danger of that; your understanding of media and the political movements underway today which involve some significant transgression of the boundaries of authority, I’m willing to bet you have a more nuanced take on this issue. What’s our condition now with regards to the edge of the wild? Is it a constantly shifting boundary, what Agamben refers to as the caesura? Does it imply a human condition interdigitated with an inhuman condition, like a werewolf, or cyborg? Does our humanity in fact find its source in the wild?

Andreas Broeckmann: The questions that you raise are of course extremely complex and very difficult to do justice in the current context. So allow me to shirk the anthropological discussion, which I guess I don’t have a particularly original opinion on anyway. When I spoke about the “wild” as an aspect of digital art a few years ago, it was in a half ironic, and half romantic way: ironic in the sense that art that makes use of digital media is technically conditioned and requires a “tamed” environment to function at all; even what is referred to as ‘glitch aesthetics’ is predicated on general functionality, the glitch being only a minor aberration, not a substantial fault. Yet, as you would gather from what I said before, I am also ‘romantically’ attached to the idea of an artistic practice that transgresses these technical functionalities and explores failure, dysfunctionality, misuse, or uncontrollability as categories of aesthetic experience. I’m thinking of artists like Gustav Metzger, Jean Tinguely, Herwig Weiser, or JODI, who in their works perform, we might claim, the potential wildness of technology. This is mostly a controlled, at times even metaphorical wildness, whereas the true wilderness of technology, if we want to go there, is probably the realm of the accident that Paul Virilio has so poignantly written about. An “art of the accident”, as we entitled a festival in Rotterdam in the late 1990s, is, I believe, only possible in the realm of metaphors.

What I’m currently wondering about is whether in our 21st-century cybernated world a notion of “nature” as something different from culture maybe disappears completely, as we have full Google-ised view and total measurability of what happens on Earth, from millimetre shifts of tectonic plates to carbon dioxide output of cattle. In such a world, there would be no room any more for the “wild”, only for different degrees of pollution on the one hand, and endangerment of species on the other…

In the long run I have trust in the finality of all existence, and the futility of all human efforts. But in the short term, that is, in our lives, I believe that we have to work to make the world a little better, or at least do our best to not make things worse than they are.