1 May – 4 August 2019

Featured image: Portrait of Kathy Acker, San Francisco, 1991. Photo: Kathy Brew

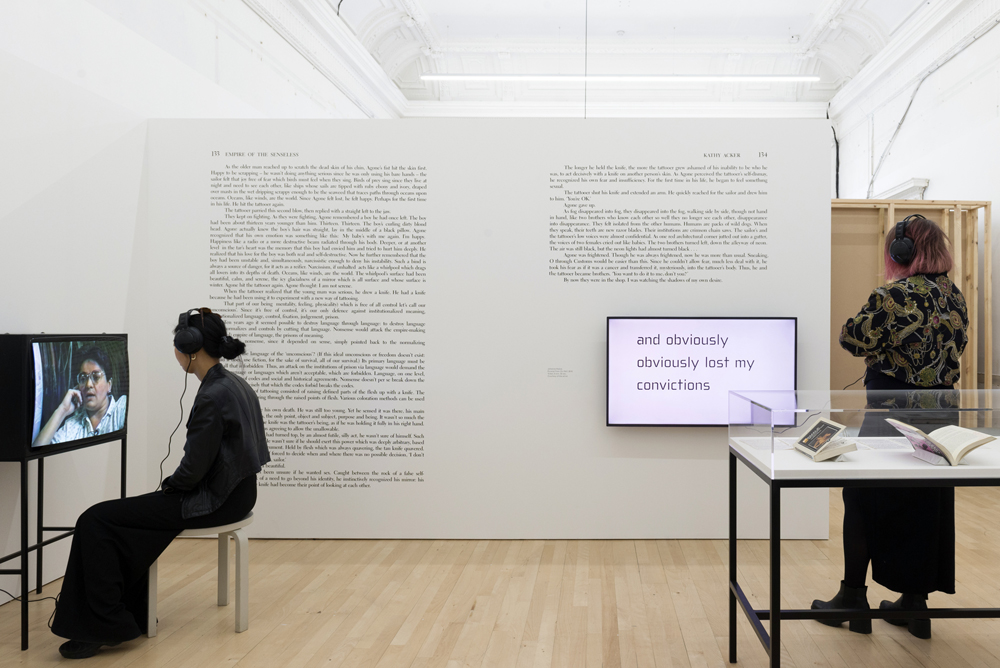

The latest exhibition at the London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts remembers the postmodernist writer Kathy Acker. The many Is in the exhibition title are suggestive of her focus on the exploration of identity and acknowledge the impact she made on the generations of artists following her. Apart from examples of Acker’s practice, such as the documentation of live readings and performances, music and text, this first exhibition dedicated to her in the UK, encompasses works by over 40 artists inspired by her legacy.

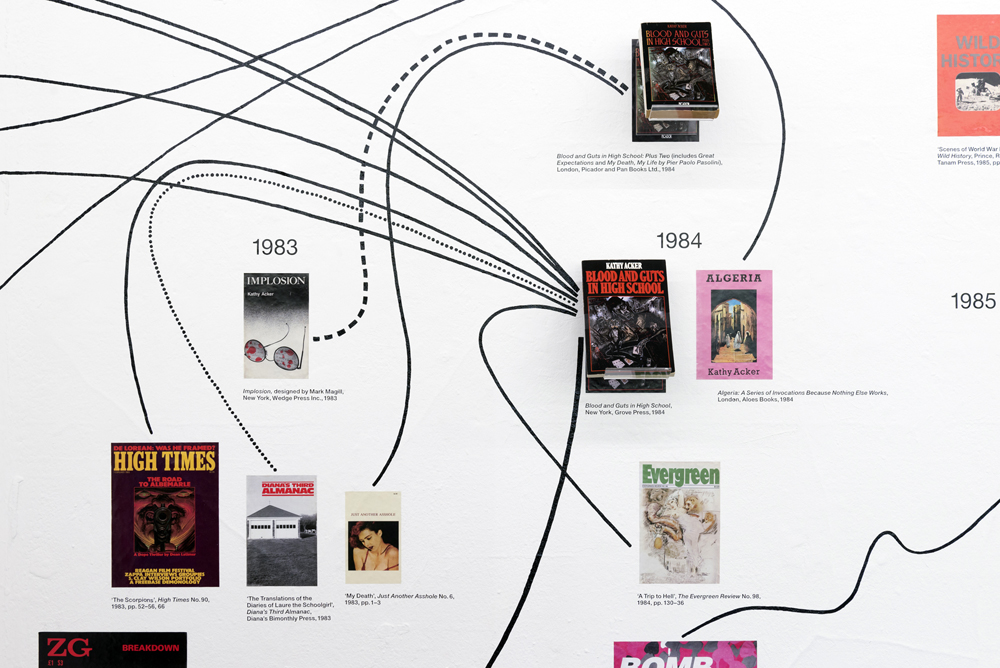

Acker’s relationship with the ICA has begun when she first moved to London, where she lived between 1983 and 1989. At that time, her anti-establishment and anti-patriarchal deconstructive philosophy fit perfectly in time with the atmosphere of the post-punk Tatcher England. She became a significant figure within the cultural landscape and a regular contributor to events at the ICA.

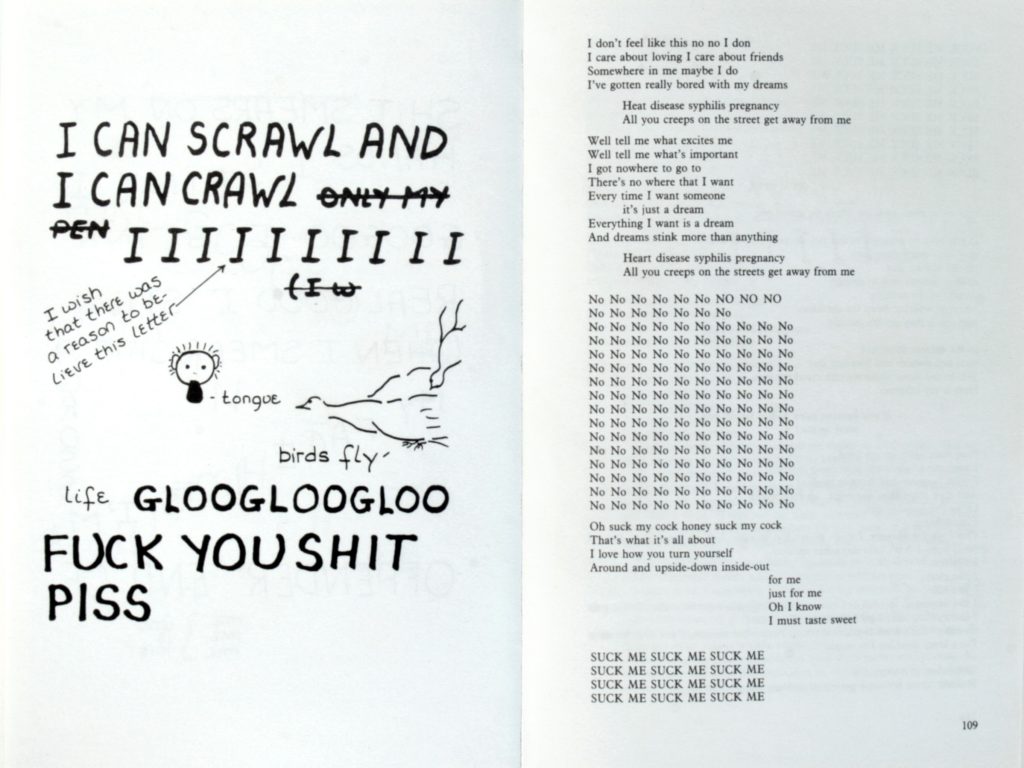

Kathy Acker was a writer who shook the punk art scene in the 70s and 80s New York. She was a lonesome figure in the East Village avant-garde, which at the time was dominated by men. In her prose, Acker often experimented with what being oneself meant. She herself said, “I was splitting the I into false and true I’s and I just wanted to see if this false I was more or less real than the true I, what are the reality levels between false and true and how it works”. Through her practice, she established a performative relationship to one’s identity, a means of exploration into the relationship between sexual desire and violence.

The language was her weapon. She treated it as a means of strong resistance towards patriarchal and heteronormative narratives in the public sphere. Throughout her writings displayed on the walls within the exhibition space, one can see her words from the book Empire of the Senseless (1994), where she declared: “Language, on one level, constitutes a set of codes and social and historical agreements. Nonsense doesn’t per se break down the codes; speaking precisely that which the codes forbid breaks the codes”. The two floors of the ICA are divided into eight sections, each corresponding to one of her books, with appropriate excerpt displayed. Her writing is at the core of the exhibition, on the walls, screens and in glass cases. There is a bit of inconsistency between the ways the literary works are displayed. On the one hand, the exhibition aims at bringing her legacy closer to the public, on the other some of them look hermeneutic when closed off behind a glass, like relics in an ethnographic museum.

However, the other works in the exhibition animate the space and the texts. The binding material between them is the preoccupation with the conflict between personal desires and the domineering narratives in society. Some of the first works to be seen are Jimi DeSana’s Masking Tape (1979) and Refrigerator (1975). The first one depicts a human figure wrapped in masking tape, only genitals exposed and the other shows a woman tied in the refrigerator. These black and white photographs contain suggestive and poetic qualities, also distinctive for Kathy Acker’s work. Further on, Acker’s pictographic “dream maps” which originally existed as large-scale drawings, are juxtaposed with works exploring the female desire in contemporary society, for instance, Reba Maybury’s The Goddess and the Worm (2015), a book telling a story of a dominatrix.

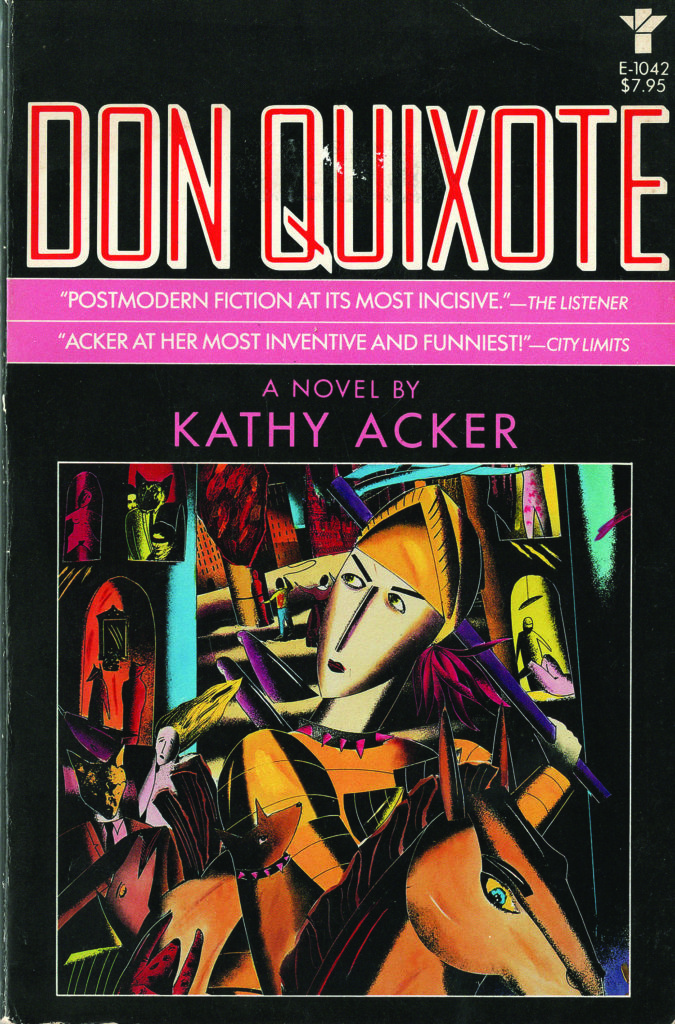

Acker critically assessed the societal norms, declared political relevance of one’s body and focused on marginalised groups. In one of her books presented in the gallery, Don Quixote (1994), the writer transformed the 17th-century canonical protagonist into a female, who becomes a knight by having an abortion and embarks on a journey to address the inequalities of Nixon’s America. Continuing to the second floor, one finds artists addressing the experiences of people who do not confine into the strict gender binary categories and the limitations of our language to describe them. At a back wall of a room, positioned opposite David Wojnarowicz’s works from the Arthur Rimbaud series, are three drawings by Jamie Crewe. Glaire takes Estradiol (2017), Potash takes Spironolactone (2016) and Saltpeter takes Verdigris (2012) show pairs of figures inscribed with the possible side effects of taking steroid hormones, compared with other substances.

The exhibition might leave the viewer in awe and with a head full of ideas. It is an ambitious project, as it addresses the integrative nature of Acker’s practice and evaluates her concepts. It is particularly successful at recognising the writer’s role in the experimental literature scene and the power of her legacy. At times when the society is becoming increasingly politically divisive and the inclusivity comes at a high price for some, it is crucial to remember the pioneers who promoted diversity in the arts. Conceptually speaking, the exhibition structure works well with the aesthetic premise of Acker’s work and creates a dialogue between all the participating artists. However, at times the experience might be overwhelming and becomes an exhibition-goer’s nightmare as it is heavily loaded with text.

I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker finishes with a wall drawing by Linda Stupart, A dead writer exists in words, and language is a type of virus (2019). In it, organic elements, serpents’ eyes and stones are tied to a blueish core resembling a cloud. Around it, there are red tentacles which enliven the virus, which spreads around the wall surface. It is mesmerising, twisted, creating a web of influences. Likewise, it corresponds with the exhibition structure, which is at times challenging to navigate, but ultimately transformative.