“Your work is so Dada, its just weird…” Even though the sentence was uttered playfully and with no foul intentions, it hit me. It sounded dismissive; in my ears, my friend just admitted disinterest. Calling something “weird” suggests withdrawal. The adjective forecloses a sense of urgency and classifies the work as a shallow event: the work is funny and quirky, slightly odd and soon becomes background noise, ’nuff said. I tried to ignore the one word review, but I will never forget when it was said, or where we were standing. I wish I had responded: “I think we already know too much to make art that is weird.” But unfortunately, I kept quiet.

In his book Noise, Water, Meat (1999), Douglas Kahn writes: “We already know too much for noise to exist.” A good 15 years after Kahn’s writing, we have entered a time dominated by the noise of crises. Hackers, disease, trade stock crashes and brutalist oligarchs make sure there is not a quiet day to be had. Even our geological time is the subject to dispute. But while insecurity dictates, no-one would dare to refer to this time as the heyday of noise. We know there is more at stake than just noise.

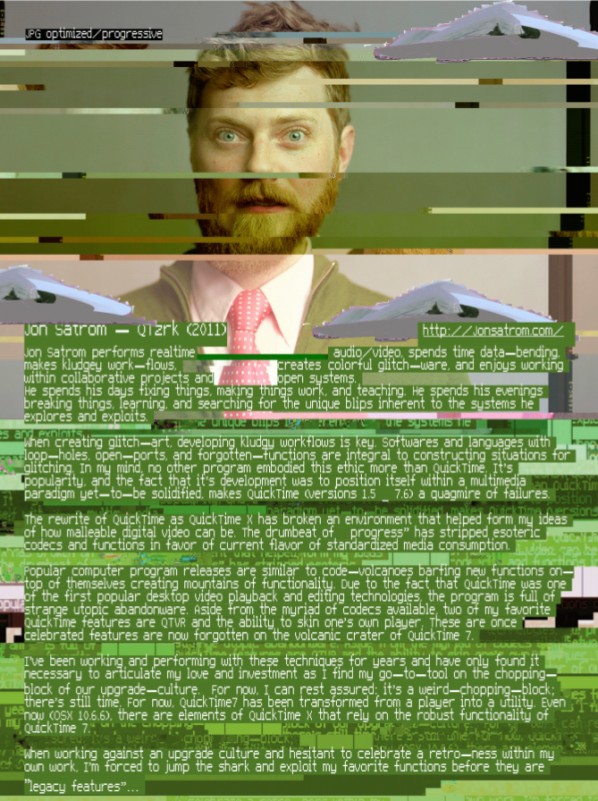

This state is reflected in critical art movements: a current generation of radical digital artists is not interested in work that is uninformed by urgency, nor can they afford to create work that is just #weird, or noisy. The work of these artists has departed from the weird and exists in an exchange that is, rather, strange. it invites the viewer to approach with inquisitiveness – it invokes a state of mind: to wonder. Consequently, these works break with tradition and create space for alternative forms, language, organisation and discourse. It is not straightforward: it is the art of creative problem creation(Jon Satrom during GLI.TC/H).

In 2016 it is easy to look at the weird aesthetics of Dada; its eclectic output is no longer unique. The techniques behind these gibberish concoctions have had a hundred years to become cultivated, even familiar. Radical art and punk alike have adopted the techniques of collage and chance and applied them as styles that are no longer inherently progressive or new. As a filter subsumed by time and fashion, Dada-esque forms of art have been morphed into weird commodities that invoke a feel of stale familiarity.

But when I take a closer look at an original Dadaist work, I enter the mind of a stranger. There is structure that looks like language, but it is not my language. It slips in and out of recognition and maybe, if I would have the chance to dialogue or question, it could become more familiar. Maybe I could even understand it. Spending more time with a piece makes it possible to break it down, to recognize its particulates and particularities, but the whole still balances a threshold of meaning and nonsense. I will never fully understand a work of Dada. The work stays a stranger, a riddle from another time, a question without an answer. The historical circumstances that drove the Dadaists to create the work, with a sentiment or mindset that bordered on madness, seems impossible to translate from one period to the next. The urgency that the Dadaists felt, while driven by their historical circumstances, is no longer accessible to me. The meaningful context of these works is left behind in another time. Which makes me question: why are so many works of contemporary digital artists still described—even dismissed—as Dada-esque? Is it even possible to be like Dada in 2016?

The answer to this question is at least twofold: it is not just the artist, but also the audience who can be responsible for claiming that an artwork is a #weird, Dada-esque anachronism. Digital art can turn Dada-esque by invoking Dadaist techniques such as collage during its production. But the work can also turn Dada-esque during its reception, when the viewer decides to describe the work as “weird like Dada.” Consequently, whether or not today a work can be weird like Dada is maybe not that interesting; the answer finally lies within the eye of the beholder. It is maybe a more interesting question to ask what makes the work of art strange? How can contemporary art invoke a mindset of wonder and the power of the critical question in a time in which noise rules and is understood to be too complex to analyse or break down?

The Dadaists invoked this power by using some kind of ellipsis (…): a tactic of strange that involves the withholding of the rules of that tactic. They employed a logic to their art that they did not share with their audience; a logic that has later been described as the logic of the madmen. Today, in a time where our daily reality has changed and our systems have grown more complex, the ellipses of mad logic (dysfunctionality) are commonplace. Weird collage is no longer strange; it is easily understood as a familiar aesthetic technique. Radical Art needs a provocative element, an element of strange that lures the viewer in and makes them think critically; that makes them question again. The art of wonder can no longer lie solely in ellipsis and the ellipsis can no longer be THE art.

This is particularly important for digital art. During the past decades, digital art has matured beyond the Dadaesque mission to create new techniques for quaint collage. Digital artists have slowly established a tradition that inquisitively opens up the more and more hermetically closed—or black boxed—technologies. Groups and movements like Critical Art Ensemble (1987), Tactical Media (1996), Glitch Art (since ±2001, and later a subgenre that is sometimes referred to as Tactical Glitch Art) and #Additivism (2015) (to name just a few) work in a reactionary, critical fashion against the status quo, engaging with the protocols that facilitate and control the fields of, for instance, infrastructure, standardization, or digital economies. The research of these artists takes place within a liminal space, where it pivots between the thresholds of digital language, such as code and algorithms, the frameworks to which data and computation adhere and the languages spoken by humans. Sometimes they use tactics that are similar to the Dadaist ellipsis. As a result, their output can border on Asemic. This practice comes close to the strangeness that was an inherent component of an original power of Dadaist art.

But an artist who still insists on explaining why a work is weirdly styled like Dada is missing out on the strange mindset that formed the inherently progressive element of Dada. Of course a work of art can be strange by other means than the tactics and techniques used in Dada. Dada is not the father of all progressive work. And not all digital art needs to be strange. But strange is a powerful affect from which to depart in a time that is desperate to ask new critical questions to counter the noise.

Thanks to Amy J. Elias and Jonathan P. Eburne

NotesImages in this article are part of the exhibition Filtering Failure curated by Julian van Aalderen and Rosa Menkman in 2011.

Catalogue of exhibition here:

http://www.slideshare.net/r00s/filtering-failure-exhibition-catalogue