On June the 16th Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger presented a new Disruption Network Lab conference entitled “AI TRAPS” to scrutinize Artificial Intelligence and automatic discrimination. The conference touched several topics from biometric surveillance to diversity in data, giving a closer look at how AI and algorithms reinforce prejudices and biases of its human creators and societies, to find solutions and countermeasures.

A focus on facial recognition technologies opened the first panel “THE TRACKED & THE INVISIBLE: From Biometric Surveillance to Diversity in Data Science” discussing how massive sets of images have been used by academic, commercial, defence and intelligence agencies around the world for their research and development. The artist and researcher Adam Harvey addressed this tech as the focal point of an emerging authoritarian logic, based on probabilistic determinations and the assumption that identities are static and reality is made through absolute norms. The artist considered two recent reports about the UK and China showing how this technology is yet unreliable and dangerous. According to data released under the UK´s Freedom of Information Law, 98% of “matches” made by the English Met police using facial recognition were mistakes. Meanwhile, over 200 million cameras are active in China and – although only 15% are supposed to be technically implemented for effective face recognition – Chinese authorities are deploying a new system of this tech to racial profile, track and control the Uighurs Muslim minority.

Big companies like Google and Facebook hold a collection of billions of images, most of which are available inside search engines (63%), on Flickr (25%) and on IMdB (11 %). Biometric companies around the world are implementing facial recognition algorithms on the pictures of common people, collected in unsuspected places like dating-apps and social media, to be used for private profit purposes and governmental mass-surveillance. They end up mostly in China (37%), US (34%), UK (21%) and Australia (4%), as Harvey reported.

Metis Senior Data Scientist Sophie Searcy, technical expert who has also extensively researched on the subject of diversity in tech, contributed to the discussion on such a crucial issue underlying the design and implementation of AI, enforcing the description of a technology that tends to be defective, unable to contextualise and consider the complexity of the reality it interacts with. This generates a lot of false predictions and mistakes. To maximise their results and reduce mistakes tech companies and research institutions that develop algorithms for AI use the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) technique. This enables to pick a few samples selected randomly from a dataset instead of analysing the whole of it for each iteration, saving a considerable amount of time. As Searcy explained during the talk with the panel moderator, Adriana Groh, this technique needs huge amount of data and tech companies are therefore becoming increasingly hungry for them.

In order to have a closer look at the relation between governments and AI-tech, the researcher and writer Crofton Black presented the study conducted with Cansu Safak at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism on the UK government’s use of big data. They used publicly available data to build a picture of companies, services and projects in the area of AI and machine learning, to map what IT systems the British government has been buying. To do so they interviewed experts and academics, analysed official transparency data and scraped governmental websites. Transparency and accountability over the way in which public money is spent are a requirement for public administrations and they relied on this principle, filing dozens of requests under the Freedom of Information Act to public authorities to get audit trails. Thus they mapped an ecosystem of the corporate nexus between UK public sector and corporate entities. More than 1,800 IT companies, from big ones like BEA System and IBM to small ones within a constellation of start-ups.

As Black explained in the talk with the moderator of the keynote Daniel Eriksson, Transparency International Head of Technology, this investigation faced systemic problems with disclosure from authorities, that do not keep transparent and accessible records. Indeed just 25% of the UK-government departments provided some form of info. Therefore details of the assignments are still unknown, but it is at least possible to list the services those companies deploying AI and machine learning can offer governments: connect data and identify links between people, objects, locations; set up automated alerts in the context of border and immigration control, spotting out changes in data and events of interest; work on passports application programs, implementing the risk-based approaches to passports application assessments; work on identity verification services using smartphones, gathering real time biometric authentications. These are just few examples.

Maya Indira Ganesh opened the panel “AI FOR THE PEOPLE: AI Bias, Ethics & the Common Good” questioning how tech and research have historically been almost always developed and conducted on prejudiced parameters, falsifying results and distorting reality. For instance, data about women’s heart attacks hadn´t been taken in consideration for decades, until doctors and scientists determined that ECG-machines calibrated on the data collected from early ´60s could neither predict heart attacks in women, nor give reliable data for therapeutic purposes, because they were trained only on male population. Just from 2007 ECG-machines were recalibrated on parameters based on data collected from female individuals. It is not possible to calculate the impact this gender inequality had on the development of modern cardiovascular medicine and on the lives of millions of women.

As the issue of algorithmic bias in tech and specifically in AI grows, all big tech firms and research institutions are writing ethics charters and establishing ethics boards sponsoring research in these topics. Detractors often refer to it as ethics-washing, which Ganesh finds a trick to mask ethics and morality as something definable in universal terms or scale: though it cannot be computed by machines, corporations need us to believe that ethics is something measurable. The researcher suggested that in such a way the abstraction and the complexity of the machine get easy to process as ethics becomes the interface used to obfuscate what is going on inside the black box and represent its abstractions. “But these abstractions are us and our way to build relations” she objected.

Ganesh wonders consequently according to what principle it shall be acceptable to train a facial recognition system, basing it on video of transgender people, as it happened in the alarming “Robust transgender face recognition” research, based on data from people undergoing hormone replacement therapy, Youtube videos, diaries and time-lapse documentation of the transition process. The HRT Transgender Dataset used to train AI to recognize transgender people worsens the harassment and the targeting that trans-people already experience daily, targeting and harming them as a group. However, it was partly financed by FBI and US-Army, confirming that law enforcement and national security agencies appear to be very interested in these kinds of datasets and look for private companies and researchers able to provide it.

In this same panel professor of Data Science and Public Policy Slava Jankin reflected on how machine learning can be used for common good in the public sector. As it was objected during the discussion moderated by Nicole Shephard, Researcher on Gender, Technology and Politics of Data, the “common good” isn’t easy to define, and like ethics it is not universally given. It could be identified with those goods that are relevant to guarantee and determine the respect of human rights and their practice. The project that Jankin presented was developed inside the Essex Centre for Data analytics in a synergic effort of developers, researches, universities and local authorities. Together, they tried to build an AI able to predict within reliability where children lacking school readiness are more likely to be found geographically, to support them in their transition and gaining competencies, considering social, economic and environmental conditions.

The first keynote of the conference was the researcher and activist Charlotte Webb, who presented her project Feminist Internet in the talk “WHAT IS A FEMINIST AI?”

<<There is not just one possible internet and there is not just one possible feminism, but only possible feminisms and possible internets>>. Starting from this assumption Webb talked about Feminist Human Computer Interaction, a discipline born to improve understandings about how gender identities and relations shape the design and use of interactive technologies. Her Feminist Internet is a no profit organisation funded to make internet a more equal space for women and other marginalized groups. Its approach combines art, design, critical thinking, creative technology development and feminism, seeking to build more responsible and bias-free AI able to empower people considering the causes of marginalization and discrimination. In her words, a feminist AI is not an algorithm and is not a system built to evangelize about a certain political or ideological cause. It is a tool that aims at recognizing differences without minimizing them for the sake of universality, meeting human needs with the awareness of the entire ecosystem in which it sits.

Tech adapts plastically to pre-existing discriminations and gender stereotypes. In a recent UN report, the ‘female’ obsequiousness and the servility expressed by digital assistants like Alexa, the Google Assistant, are defined as example of gender biases coded into tech products, since they are often projected as young women. They are programmed to be submissive and accept abuses. As stated by Feldman (2016) by encouraging consumers to understand the objects that serve them as women, technologists abet the prejudice by which women are considered objects. With her projects, Webb pushes to create alternatives that educate to shift this systemic problem – rather than complying with market demands – first considering that there is a diversity crisis in the AI sector and in the Silicon Valley. Between 2.5 and 4% of Google, Facebook and Microsoft employees are black, whilst there are no public data on transgender workers within these companies. Moreover, as Webb pointed out, just 22% of the people building AI right now are female, only 18% of authors at major AI-conferences are women, whilst over 80% of AI-professors are men. Considering companies with decisive impact on society women comprise only 15% of AI research staff at Facebook and 10% in Google.

Women, people of colour, minorities, LGBTQ and marginalized groups are substantially not deciding about designing and implementing AI and algorithms. They are excluded from the processes of coding and programming. As a result the work of engineers and designers is not inherently neutral and the automated systems that they build reflect their perspectives, preferences, priorities and eventually their bias.

Washington Tech Policy Advisor Mutale Nkonde focused on this issue in her keynote “RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN THE AGE OF AI.” She opened her dissertation reporting that Google´s facial intelligence team is composed by 893 people, and just one is a black woman, an intern. Questions, answers and predictions in their technological work will always reflect a political and socioeconomic point of view, consciously or unconsciously. A lot of the tech-people confronted with this wide-ranging problem seem to undermine it, showing colour-blindness tendencies about what impacts their tech have on minorities and specifically black people. Historically credit scores are correlated with racist segregated neighbourhoods and risk analyses and predictive policing data are corrupted by racist prejudice, leading to biased data collection reinforcing privileges. Without a conscious effort to address racism in technology, new technologies will replicate old divisions and conflicts. By instituting policies like facial recognition we just replicate rooted behaviours based on racial lines and gender stereotypes mediated by algorithms. Nkonde warns that civil liberties need an update for the era of AI, advancing racial literacy in Tech.

In a talk with the moderator, the writer Rhianna Ilube, the keynote Nkonde recalled that in New York´s poor and black neighbourhood with historically high crime and violence rates, Brownsville, a private landlord in social housing wanted to exchange keys for facial recognition software, so that either people accept surveillance, or they lose their homes. The finding echoes wider concerns about the lack of awareness of racism. Nkonde thinks that white people must be able to cope with the inconvenience of talking about race, with the countervailing pressures and their lack of cultural preparation, or simply the risk to get it wrong. Acting ethically isn´t easy if you do not work on it and many big tech companies just like to crow about their diversity and inclusion efforts, disclosing diversity goals and offering courses that reduce bias. However, there is a high level of racial discrimination in tech sector and specifically in the Silicon Valley, at best colour-blindness – said Nkonde – since many believe that racial classification does not limit a person’s opportunities within the society, ignoring that there are instead economic and social obstacles that prevent full individual development and participation, limiting freedom and equality, excluding marginalized and disadvantaged groups from the political, economic, and social organization. Nkonde concluded her keynote stressing that we need to empower minorities, providing tools that allow overcoming autonomously socio-economic obstacles, to fully participate in society. It is about sharing power, taking in consideration the unconscious biases of people, for example starting from those designing the technology.

The closing panel “ON THE POLITICS OF AI: Fighting Injustice & Automatic Supremacism” discussed the effect of a tool shown to be not neutral, but just the product of the prevailing social economical model.

Dia Kayyali, Leader of the Tech and Advocacy program at WITNESS, described how AI is facilitating white supremacy, nationalism, racism and transphobia, recalling the dramatic case of the Rohingya persecution in Myanmar and the oppressive Chinese social score and surveillance systems. Pointing out critical aspects the researcher reported the case of the Youtube anti-extremism-algorithm, which removed thousands of videos documenting atrocities in Syria in an effort to purge hate speech and propaganda from its platform. The algorithm was trained to automatically flag and eliminate content that potentially breached its guidelines and ended up cancelling documents relevant to prosecute war crimes. Once again, the absence of the ability to contextualize leads to severe risks in the way machines operate and make decisions. Likewise, applying general parameters without considering specificities and the complex concept of identity, Facebook imposed in 2015 new policies and arbitrarily exposed drag queens, trans people and other users at risk, who were not using their legal names for safety and privacy reasons, including domestic violence and stalking.

Researcher on gender, tech and (counter) power Os Keyes considered that AI is not the problem, but the symptom. The problem are the structures creating AI. We live in an environment where few highly wealthy people and companies are ruling all. We have bias in AI and tech because their development is driven by exactly those same individuals. To fix AI we have to change requirements and expectations around it; we can fight to have AI based on explainability and transparency, but eventually if we strive to fix AI and do not look at the wider picture, in 10 years the same debate over another technology will arise. Keyes considered that since its very beginning AI-tech was discriminatory, racialized and gendered, because society is capitalist, racist, homo-transphobic and misogynistic. The question to pose is how we start building spaces that are prefigurative and constructed on values that we want a wider society to embrace.

As the funder and curator of the Disruption Network Lab Tatiana Bazzichelli pointed out during the moderation of this panel, the problem of bias in algorithms is related to several major “bias traps” that algorithm-based prediction systems fail to win. The fact that AI is political – not just because of the question of what is to be done with it, but because of the political tendencies of the technology itself – is the real aspect to discuss.

In his analysis of the political effects of AI, Dan McQuillan, Lecturer in Creative and Social Computing from the London University, underlined that while the reform of AI is endlessly discussed, there seems to be no attempt to seriously question whether we should be using it at all. We need to think collectively about ways out, learning from and with each other rather than relying on machine learning. Countering thoughtlessness of AI with practices of solidarity, self-management and collective care is what he suggests because bringing the perspective of marginalised groups at the core of AI practice, it is possible to build a new society within the old, based on social autonomy.

What McQuillan calls the AI realism appears to be close to the far-right perspective, as it trivialises complexity and naturalises inequalities. The character of learning through AI implicates indeed reductive simplifications, and simplifying social problems to matters of exclusion is the politics of populist and Fascist right. McQuillan suggests taking some guidance from the feminist and decolonial technology studies that have cast doubt on our ideas about objectivity and neutrality. An antifascist AI, he explains, shall involve some kinds of people’s councils, to put the perspective of marginalised groups at the core of AI practice and to transform machine learning into a form of critical pedagogy.

Pic 7: Dia Kayyali, Os Keyes, Dan McQuillan and Tatiana Bazzichelli during the panel “ON THE POLITICS OF AI: Fighting Injustice & Automatic Supremacism”

We see increasing investment on AI, machine learning and robots. Automated decision-making informed by algorithms is already a predominant reality, whose range of applications has broadened to almost all aspects of life. Current ethical debates about the consequences of automation focus on the rights of individuals and marginalized groups. However, algorithmic processes generate a collective impact too, that can only be addressed partially at the level of individual rights, as it is the result of a collective cultural legacy. A society that is soaked in racial and sexual discriminations will replicate them inside technology.

Moreover, when referring to surveillance technology and face recognition software, existing ethical and legal criteria appear to be ineffective and a lack of standards around their use and sharing just benefit its intrusive and discriminatory nature.

Whilst building alternatives we need to consider inclusion and diversity: If more brown and black people would be involved in the building and making of these systems, there would be less bias. But this is not enough. Automated systems are mostly trying to identify and predict risk, and risk is defined according to cultural parameters that reflect the historical, social and political milieu, to give answers able to fit a certain point of view and make decisions. What we are and where we are as a collective, what we have achieved and what we still lack culturally is what is put in software to make those same decisions in the future. In such a context a diverse team within a discriminatory conflictual society might find ways to flash the problem of bias away, but it will get somewhere else.

The truth is that automated discrimination, racism and sexism are integrated in tech-infrastructures. New generation of start-ups are fulfilling authoritarian needs, commercialising AI-technologies, automating biases based on skin colour and ethnicity, sexual orientation and identity. They develop censored search engine and platforms for authoritarian governments and dictators, refine high-tech military weapons training them using facial recognition on millions of people without their knowledge. Governments and corporations are developing technology in ways that threaten civil liberties and human rights. It is not hard to imagine the impact of the implementation of tools for robotic gender recognition, within countries were non-white, non-male and non-binary individuals are discriminated. Bathrooms and changing rooms that open just by AI gender-detection, or cars that start the engine just if a man is driving, are to be expected. Those not gender conforming, who do not fit traditional gender structures, will end up being systematically blocked and discriminated.

Open source, transparency and diversity alone will not defeat colour-blinded attitudes, reactionary backlashes, monopolies, other-directed homologation and cultural oppression by design. As it was discussed in the conference, using algorithms to label people based on sexual identity or ethnicity has become easy and common. If you build a technology able to catalogue people by ethnicity or sexual identity, someone will exploit it to repress genders or ethnicities, China shows.

In this sense, no better facial recognition is possible, no mass-surveillance tech is safe and attempts at building good tech will continue to fail. To tackle bias, discrimination and harm in AI we have to integrate research on and development of technology with all of the humanities and social sciences, deciding to consciously create a society where everybody could participate to the organisation of our common future.

Curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli and developed in cooperation with Transparency International, this Disruption Network Lab-conference was the second of the 2019 series The Art of Exposing Injustice.

More info, all its speakers and thematic could be found here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/ai-traps

The videos of the conference are on Youtube and the Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter and Facebook.

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for its Newsletter and get informed about its conferences, ongoing researches and projects. The next Disruption Network Lab event “Citizen of evidence” is planned for September 20-21 in Kunstquartier Bethanien Berlin. Make sure you don´t miss it!

Photocredits: Maria Silvano for Disruption Network Lab

In which the spectre of the Luddite software engineer is raised, in an AI-driven future where programming languages become commercially redundant, and therefore take on new cultural significance.

In 1812, Lord Byron dedicated his first speech in the House of Lords to the defence of the machine breakers, whose violent acts against the machines replacing their jobs prefigured large scale trade unionism. We know these machine breakers as Luddites, a movement lead by the mysterious, fictional character of General Ludd, although curiously, Byron doesn’t refer to them as such in his speech. With the topic of post-work in the air at the moment, the Luddite movements are instructive; The movement was comprised of workers finding themselves replaced by machines, left not in a post-work Utopia, but in a state of destitution and starvation. According to Hobsbawm (1952), if Luddites broke machines, it was not through a hatred of technology, but through self-preservation. Indeed, when political economist David Ricardo (1921) raised “the machinery question” he did so signalling a change in his own mind, from a Utopian vision where the landlord, capitalist, and labourer all benefit from mechanisation, to one where reduction in gross revenue hits the labourer alone. Against the backdrop of present-day ‘disruptive technology’, the machinery question is as relevant as ever.

A few years after his speech, Byron went on to father Ada Lovelace, the much celebrated prototypical software engineer. Famously, Ada Lovelace cooperated with Charles Babbage on his Analytical Engine; Lovelace exploring abstract notions of computation at a time when Luddites were fighting against their own replacement by machines. This gives us a helpful narrative link between mill workers of the industrial revolution, and software engineers of the information revolution. That said, Byron’s wayward behaviour took him away from his family, and he deserves no credit for Ada’s upbringing. Ada was instead influenced by her mother Annabella Byron, the anti-slavery and women’s rights campaigner, who encouraged Ada into mathematics.

Today, general purpose computing is becoming as ubiquitous as woven fabric, and is maintained and developed by a global industry of software engineers. While the textile industry developed out of worldwide practices over millennia, deeply embedded in culture, the software industry has developed over a single lifetime, the practice of software engineering literally constructed as a military operation. Nonetheless, the similarity between millworkers and programmers is stark if we consider weaving itself as a technology. Here I am not talking about inventions of the industrial age, but the fundamental, structural crossing of warp and weft, with its extremely complex, generative properties to which we have become largely blind since replacing human weavers with powerlooms and Jacquard devices. As Ellen Harlizius-Klück argues, weaving has been a digital art from the very beginning.

Software engineers are now threatened under strikingly similar circumstances, thanks to breakthroughs in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and “Deep Learning” methods, taking advantage of the processing power of industrial-scale server farms. Jen-Hsun Hu, chief executive of NVIDIA who make some of the chips used in these servers is quoted as saying that now, “Instead of people writing software, we have data writing software”. Too often we think of Luddites as those who are against technology, but this is a profound misunderstanding. Luddites were skilled craftspeople working with technology advanced over thousands of years, who only objected once they were replaced by technology. Deep learning may well not be able to do everything that human software engineers can do, or to the same degree of quality, but this was precisely the situation in the industrial revolution. Machines cannot make the same woven structures as hands, to the same quality, or even at the same speed at first, but the Jacquard mechanism replaced human drawboys anyway.

As a thought experiment then, let’s imagine a future where entire industries of computer programmers are replaced by AI. These programmers would either have to upskill to work in Deep Learning, find something else to do, or form a Luddite movement to disrupt Deep Learning algorithms. The latter case might even seem plausible when we recognise the similarities between the Luddite movement and Anonymous, both outwardly disruptive, lacking central organisation, and lead by an avatar: General Ludd in the case of the Luddites, and Guy Fawkes in the case of Anonymous.

Let’s not dwell on Anonymous though. Instead try to imagine a Utopia in which current experiments in Universal Basic Income are proved effective, and software engineers are able to find gainful activity without the threat of destitution. The question we are left with then is not what to do with all the software engineers, but what to do with all the software? With the arrival of machine weaving and knitting, many craftspeople continued hand weaving and handknitting in their homes and in social clubs for pleasure rather than out of necessity. This was hardly a surprise, as people have always made fabric, and indeed in many parts of the world handweaving has remained the dominant form of fabric making. Through much of the history of general purpose computing however, any cultural context for computer programming has been a distant second to its industrial and military contexts. There has of course been a hackerly counter-culture from the beginning of modern-day computing, but consider that the celebrated early hackers in MIT were funded by the military while Vietnam flared, and the renowned early Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition of electronic art included presentations by General Motors and Boeing, showing no evidence of an undercurrent of political dissent. Nonetheless, I think a Utopian view of the future is possible, but only once Deep Learning renders the craft of programming languages useless for such military and corporate interests.

Looking forward, I see great possibilities. All the young people now learning how to write code for industry may find that the industry has disappeared by the time they graduate, and that their programming skills give no insight into the workings of Deep Learning networks. So, it seems that the scene is set for programming to be untethered from necessity. The activity of programming, free from a military-industrial imperative, may become dedicated almost entirely to cultural activities such as music-making and sculpture, augmenting human abilities to bring understanding to our own data, breathing computational pattern into our lives. Programming languages could slowly become closer to natural languages, simply by developing through use while embedded in culture. Perhaps the growing practice of Live Coding, where software artists have been developing computer languages for creative coding, live interaction and music-making over the past two decades, are a precursor to this. My hope is that we will begin to think of code and data in the same way as we do of knitting patterns and weaving block designs, because from my perspective, they are one and the same, all formal languages, with their structures intricately and literally woven into our everyday lives.

So in order for human cultures to fully embrace the networks and data of the information revolution, perhaps we should take lessons from the Luddites. Because they were not just agents of disruption, but also agents against disruption, not campaigning against technology, but for technology as a positive cultural force.

This article was written by Alex while sound artist in residence in the Open Data Institute, London, as part of the Sound and Music embedded programme.

Featured Image: Gerald Raunig, Dividuum, Semiotext (e)/ MIT Press

Gerald Raunig’s book on the concept and the genealogy of “dividuum” is a learned tour de force about what is supposed to be replacing the individual, if the latter is going to “break down” – as Raunig suggests. The dividuum is presented as a concept with roots in Epicurean and Platonic philosophy that has been most controversially disputed in medieval philosophy and achieves new relevance in our days, i.e. the era of machinic capitalism.

The word dividuum appears for the first time in a comedy by Plautus from the year 211 BC . “Dividuom facere” is Ancient Latin for making something divisible that has not been able to be divided before. This is at the core of dividuality that is presented here as a counter-concept to individuality.

Raunig introduces the notion of dividuality by presenting a section of the comedy “Rudens” by Plautus. The free citizen Daemones is faced with a problem: His slave Gripus pulls a treasure from the sea that belongs to the slave-holder Labrax and demands his share. Technically the treasure belongs to the slave-holder, and not to the slave. Yet, in terms of pragmatic reasoning there would have been no treasure if the slave hadn’t pulled it from the sea and declared it as found to his master. Daemones comes up with a solution that he calls “dividuom facere”. He assigns half of the money to Labrax, who is technically the owner, if he sets free Ampelisca, a female slave whom Gripus loves. The other half of the treasure is assigned to Gripus for buying himself out of slavery. This will allow Gripus to marry Ampelisca and it will also benefit the patriarch’s wealth. Raunig points out that Daemones transfers formerly indivisible rights and statuses – that of the finder and that of the owner – into a multiple assignment of findership and ownership.

We will later in the book see how Raunig sees this magic trick being reproduced in contemporary society, when we turn or are turned into producer/consumers, photographers/photographed, players/instruments, surveyors/surveyed under the guiding imperative of “free/ voluntary obedience [freiwilliger Gehorsam]”.

The reader need not be scared by text sections in Ancient Greek, Ancient Latin, Modern Latin or Middle High German, as Raunig provides with translations. The translator Aileen Derieg must be praised for having undertaken this difficult task once more for the English language version of the book. It can however be questioned whether issues of proper or improper translation of Greek terms into Latin in Cicero’s writings in the first century BC should be discussed in the context of this book. This seems to be a matter for an old philology publication, rather than for a Semiotext(e) issue.

It is, however, interesting to see how Raunig’s genealogy of the dividuum portraits scholastic quarrels as philosophic background for the development of the dividuum. With the trinity of God, Son of God and the Holy Spirit the Christian dogma faced a problem of explaining how a trinity and a simultaneous unity of God could be implemented in a plausible and consistent fashion. Attempts to speak of the three personae (masks) of God or to propose that father, son and spirit were just three modes (modalism) of the one god led to accusations of heresy. Gilbert de Poitiers’ “rationes” were methodological constructions that claimed at least two different approaches to reasoning: One in the realm of the godly and the other in the creaturely realm. Unity and plurality could in this way be detected in the former and the latter realm respectively without contradicting each other. Gilbert arrives at a point where he concludes that “diversity and conformity are not to be seen as mutually exclusive, but rather as mutually conditional.” Dissimilarity is a property of the individual that forms a whole in space and time. The dividual, however, is characterized by similarity, or in Gilbert de Poitiers’ words: co-formity. “Co-formity means that parts that share their form with others assemblage along the dividual line. Dividuality emerges as assemblage of co-formity to form-multiplicity. The dividual type of singularity runs through various single things according to their similar properties. … This co-formity, multi-formity constitutes the dividual parts as unum dividuum.”

In contemporary society the one that can be divided, unum dividuum, can be found in “samples, data, markets, or ‘banks’”. Developing his argument in the footsteps of Gilles Deleuze, Gerald Raunig critically analyses Quantified Self, Life-Logging, purchases from Amazon, film recommendations from Netflix, Big Data and Facebook. “Facebook needs the self-division of individual users just as intelligence agencies continue to retain individual identities. Big Data on the other hand, is less interested in individuals and just as little interested in a totalization of data, but all the more so in data sets that are freely floating and as detailed as possible, which it can individually traverse.” In the beginning “Google & Co. tailor search results individually (geographical position, language, individual search history, personal profile, etc.” The qualitative leap from individual data to dividual data happens when the ”massive transition to machinic recommendation [happens], which save the customer the trouble of engaging in a relatively undetermined search process.” With this new form of searching the target of my search request is generated by my search history and by an opaque layer of preformatted selection criteria. The formerly individual subject of the search process turns into a dividuum that is asking for data and providing data, that is replying to the subject’s own questions and becomes interrogator and responder in one. This is where Gilbert de Poitiers’ unum dividuum reappers in the disguise of contemporary techno-rationality.

Raunig succeeds in creating a bridge from ancient and medieval texts to contemporary technologies and application areas. He discusses Arjun Appadurai’s theory of the “predatory dividualism”, speculates about Lev Sergeyevich Termen’s dividual machine from the 1920s that created a player that is played by technology, and theorizes on “dividual law” as observed in Hugo Chávez’ presidency or the Ecuadorian “Constituyente” from 2007. The reviewer mentions these few selected fields of Raunig’s research to show that his book is not far from an attempt to explain the whole world seamlessly from 210 BC to now, and one can’t help feeling overwhelmed by the text.

For some readers Raunig’s manneristic style of writing might be over the top, when he calls the paragraphs of his book “ritornelli”, when he introduces a chapter in the middle of his arguments that just lists people whom he wants to thank, or when he poetically goes beyond comprehensiveness and engages with grammatical extravaganzas in sentences like this one: “[: Crossing right through space, through time, through becoming and past. Eternal queer return. An eighty-thousand or roughly 368-old being traversing multiple individuals.”

It is obvious that Gerald Raunig owes the authors of the Anti-Œdipe stylistic inspirations, theoretical background and a terminological basis, when he talks of the molecular revolutions, desiring machines, the dividuum, deterritorialization, machinic subservience and lines of flight. He manages to contextualise a concept that has historic weight and current relevance within a wide field of cultural phenomena, philosophical positions, technological innovation and political problems. A great book.

Dividuum

Machinic Capitalism and Molecular Revolution

By Gerald Raunig

Translated by Aileen Derieg

Semiotext(e) / MIT Press

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/dividuum

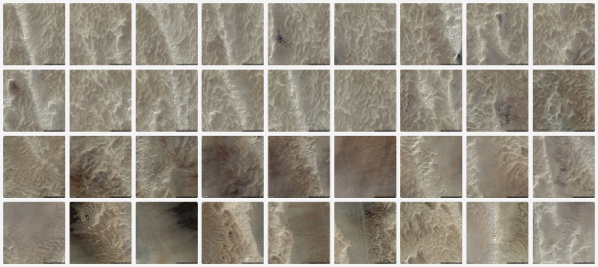

The new project by Guido Segni is so monumental in scope and so multitudinous in its implications that it can be a bit slippery to get a handle on it in a meaningful way. A quiet desert failure is one of those ideas that is deceptively simple on the surface but look closer and you quickly find yourself falling down a rabbit-hole of tangential thoughts, references, and connections. Segni summarises the project as an “ongoing algorithmic performance” in which a custom bot programmed by the artist “traverses the datascape of Google Maps in order to fill a Tumblr blog and its datacenters with a remapped representation of the whole Sahara Desert, one post at a time, every 30 minutes.”1

Opening the Tumblr page that forms the core component of A quiet desert failure it is hard not to get lost in the visual romanticism of it. The page is a patchwork of soft beiges, mauves, creams, and threads of pale terracotta that look like arteries or bronchia. At least this morning it was. Since the bot posts every 30 minutes around the clock, the page on other days is dominated by yellows, reds, myriad grey tones. Every now and then the eye is captured by tiny remnants of human intervention; something that looks like a road, or a small settlement; a lone, white building being bleached by the sun. The distance of the satellite, and thus our vicarious view, from the actual terrain (not to mention the climate, people, politics, and more) renders everything safely, sensuously fuzzy; in a word, beautiful. Perhaps dangerously so.

As is the nature of social media platforms that prescribe and mediate our experience of the content we access through them, actually following the A quiet desert failure Tumblr account and encountering each post individually through the template of the Tumblr dashboard provides a totally different layer to the work. On the one hand this mode allows the occasional stunningly perfect compositions to come to the fore – see image below – some of these individual ‘frames’ feel almost too perfect to have been lifted at random by an aesthetically indifferent bot. Of course with the sheer scope of visual information being scoured, packaged, and disseminated here there are bound to be some that hit the aesthetic jackpot. Viewed individually, some of these gorgeous images feel like the next generation of automated-process artworks – a link to the automatic drawing machines of, say, Jean Tinguely. Although one could also construct a lineage back to Duchamp’s readymades.

Segni encourages us to invest our aesthetic sensibility in the work. On his personal website, the artist has installed on his homepage a version of A quiet desert failure that features a series of animated digital scribbles overlaid over a screenshot of the desert images the bot trawls for. Then there is the page which combines floating, overlapping, translucent Google Maps captures with an eery, alternately bass-heavy then shrill, atmospheric soundtrack by Fabio Angeli and Lorenzo Del Grande. The attention to detail is noteworthy here; from the automatically transforming URL in the browser bar to the hat tip to themes around “big data” in the real time updating of the number of bytes of data that have been dispersed through the project, Segni pushes the limits of the digital medium, bending and subverting the standardised platforms at every turn.

But this is not art about an aesthetic. A quiet desert failure did begin after the term New Aesthetic came to prominence in 2012, and the visual components of the work do – at least superficially – fit into that genre, or ideology. Thankfully, however, this project goes much further than just reflecting on the aesthetic influence of “modern network culture”2 and rehashing the problematically anthropocentric humanism of questions about the way machines ‘see’. Segni’s monumental work takes us to the heart of some of the most critical issues facing our increasingly networked society and the cultural impact of digitalisation.

The Sahara Desert is the largest non-polar desert in the world covering nearly 5000 km across northern Africa from the Atlantic ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east, and ranging from the Mediterranean Sea in the north almost 2000 km south towards central Africa. The notoriously inhospitable climate conditions combine with political unrest, poverty, and post-colonial power struggles across the dozen or so countries across the Sahara Desert to make it surely one of the most difficult areas for foreigners to traverse. And yet, through the ‘wonders’ of network technologies, global internet corporations, server farms, and satellites, we can have a level of access to even the most problematic, war-torn, and infrastructure-poor parts of the planet that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago.

A quiet desert failure, through the sheer scope of the piece, which will take – at a rate of one image posted every 30 minutes – 50 years to complete, draws attention to the vast amounts of data that are being created and stored through networked technologies. From there, it’s only a short step to wondering about the amount of material, infrastructure, and machinery required to maintain – and, indeed, expand – such data hoarding. Earlier this month a collaboration between private companies, NASA, and the International Space Station was announced that plans to launch around 150 new satellites into space in order to provide daily updating global earth images from space3. The California-based company leading the project, Planet Labs, forecasts uses as varied as farmers tracking crops to international aid agencies planning emergency responses after natural disasters. While it is encouraging that Planet Labs publishes a code of ethics4 on their website laying out their concerns regarding privacy, space debris, and sustainability, there is precious little detail available and governments are, it seems, hopelessly out of date in terms of regulating, monitoring, or otherwise ensuring that private organisations with such enormous access to potentially sensitive information are acting in a manner that is in the public interest.

The choice of the Sahara Desert is significant. The artist, in fact, calls an understanding of the reasons behind this choice “key to interpret[ing] the work”. Desertification – the process by which an area becomes a desert – involves the rapid depletion of plant life and soil erosion, usually caused by a combination of drought and overexploitation of vegetation by humans.5 A quiet desert failure suggests “a kind of desertification taking place in a Tumblr archive and [across] the Internet.”6 For Segni, Tumblr, more even than Instagram or any of the other digitally fenced user generated content reichs colonising whatever is left of the ‘free internet’, is symbolic of the danger facing today’s Internet – “with it’s tons of posts, images, and video shared across its highways and doomed to oblivion. Remember Geocities?”7

From this point of view, the project takes on a rather melancholic aspect. A half-decade-long, stately and beautiful funeral march. An achingly slow last salute to a state of the internet that doesn’t yet know it is walking dead; that goes for the technology, the posts that will be lost, the interior lives of teenagers, artists, nerds, people who would claim that “my Tumblr is what the inside of my head looks like”8 – a whole social structure backed by a particular digital architecture, power structure, and socio-political agenda.

The performative aspect of A quiet desert failure lies in the expectation of its inherent breakdown and decay. Over the 50 year duration of the performance – not a randomly selected timeframe, but determined by Tumblr’s policy regulating how many posts a user can make in a day – it is likely that one or more of the technological building blocks upon which the project rests will be retired. In this way we see that the performance is multi-layered; not just the algorithm, but also the programming of the algorithm, and not just that but the programming of all the algorithms across all the various platforms and net-based services incorporated, and not just those but also all the users, and how they use the services available to them (or don’t), and how all of the above interact with new services yet to be created, and future users, and how they perform online, and basically all of the whole web of interconnections between human and non-human “actants” (as defined by Actor- network theory) that come together to make up the system of network, digital, and telecommunications technologies as we know them.

Perhaps the best piece I know that explains this performativity in technology is the two-minute video New Zealand-based artist Luke Munn made for my Net Work Compendium – a curated collection of works documenting the breadth of networked performance practices. The piece is a recording of code that displays the following text, one word at a time, each word visible for exactly one second: “This is a performance. One word per second. Perfectly timed, perfectly executed. All day, every day. One line after another. Command upon endless command. Each statement tirelessly completed. Zero one, zero one. Slave to the master. Such was the promise. But exhaustion is inevitable. This memory fills up. Fragmented and leaking. This processor slows down. Each cycle steals lifecycle. This word milliseconds late. That loop fractionally delayed. Things get lost, corrupted. Objects become jagged, frozen. The CPU is oblivious to all this. Locked away, hermetically sealed, completely focused. This performance is always perfect.”

Guido Segni’s A quiet desert failure is, contrary to its rather bombastic scale, a finely attuned and sensitively implemented work about technology and our relationship to it, obsolescence (planned and otherwise), and the fragility of culture (notice I do not write “digital” culture) during this phase of rapid digitalisation. The work has been released as part of The Wrong – New Digital Art Biennale, in an online pavilion curated by Filippo Lorenzin and Kamilia Kard, inexactitudeinscience.com.

Erica Scourti’s work addresses the mediation of personal and collective experience through language and technology in the net-worked regime of contemporary culture. Using autobiographical source material, as well as found text collected from the internet displaced into social space, her work explores communication, and particularly the mediated intimacy engendered by a digital paradigm.

The variable status and job of the artist is humorously fore-grounded in her work, assuming alternating between the role activist, ‘always-on’ freelancer, healer of social bonds and a self-obsessed documenter of quotidian experience.

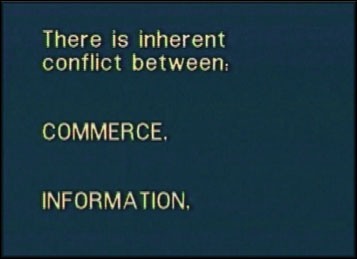

Millions are blissfully unaware of the technological forces at work behind the scenes when we use social network platforms, mobile phones and search engines. The Web is bulging with information. What lies behind the content of the systems we use everyday are algorithms, designed to mine and sort through all the influx of diverse data. The byproduct of this mass online activity is described by marketing companies as data exhaust and seen as a deluge of passively produced data. All kinds of groups have vested interests in the collection and analysis of the this data quietly collected while users pursue their online activities and interests; with companies wanting to gain more insight into our web behaviours so that they can sell more products, government agencies observing attitudes around austerity cuts, and carrying out anti-terrorism surveillance.

Felix Stalder and Konrad Becker, editors of Deep Search: The Politics of Search Beyond Google,[1] ask whether our autonomies are at risk as we constantly adapt and tailor our interactions to the demands of surveillance and manipulation through social sorting. We consciously and unconsciously collide with the algorithm as it affects every field of human endeavour. Deep Search illuminates the politics and power play that surround the development and use of search engines.

But, what can we learn from other explorers and their own real-life adventures in a world where a battle of consciousness between human and machine is fought out daily?

Artist Erica Scourti spent months of her life in this hazy twilight zone. I was intrigued to know more about her strange adventure and the chronicling of a life within the ad-triggering keywords of the “free” Internet marketing economy.

Marc Garrett: In March 2012, you began the long Internet based, networked art project called Life in AdWords, in which you wrote and emailed a daily diary to your Gmail account and performed regular webcams where you read out to the video lists suggested keywords. These links as you say are “clusters of relevant ads, making visible the way we and our personal information are the product in the ‘free’ Internet economy.”

Firstly, what were the reasons behind what seems to be a very demanding project?

Erica Scourti: Simply put, I wanted to make visible in a literal and banal way how algorithms are being deployed by Google to translate our personal information – in this case, the private correspondence of email content – into consumer profiles, which advertisers pay to access. It’s pretty widespread knowledge by now that this data ends up refining the profile marketers have of us, hence being able to target us more effectively and efficiently; just as in Carlotta Schoolman and Richard Serra’s 1973 video TV Delivers People,[2] which argues that the function of TV is to deliver viewers to advertisers, we could say the same about at least parts of the internet; we are the commodities delivered to the advertisers, which keep the Web 2.0 economy ‘free’. The self as commodity is foregrounded in this project, a notion eerily echoed by the authors who coined the term ‘experience economy’, who are now promoting the idea of the transformation economy in which, as they gleefully state, “the customer is the product!”, whose essential desire is to be changed. The notion of transformation and self-betterment, and how it relates to female experience especially within our networked paradigm is something I’m really interested in.

As Eli Pariser has pointed out with his notion of filter bubbles, the increasingly personalised web employs algorithms to invisibly edit what we see, so that our Google searches and Facebook news feeds reflect back what we are already interested in, creating a kind of solipsistic feedback loop. Life in AdWords plays on this solipsism, since it’s based on me talking to myself (writing a diary), then emailing it to myself and then repeating to the mirror-like webcam a Gmail version of me. This mirror-fascination also implies a highly narcissistic aspect, which echoes the preoccupation with self-performance that the social media stage seems to engender; but narcissism is also one of the accusations often leveled at women’s mediated self-presentation in particular, despite, as Sarah Gram notes in a great piece on the selfie, [3] it being nothing less than what capital requires of them.

![Girl with a Pearl Earring and a Silver Camera. Digital mashup after Johannes Vermeer, attributed to Mitchell Grafton. c.2012. [4]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/vermeer_selfie.jpg)

And as this project is a form of autobiography and diary-writing, it could also be seen as both narcissistic and as asserting the importance of personal experience and emotions in the construction of a humanist, unified subject. Instead, I wanted to experiment with a way of writing a life story that operated somewhere between software and self, so that, as Donna Harraway says “it is not clear who makes and who is made in the relation between human and machine”. Part of the humour of the project arises from the dissonance between the staged realism of the webcam (and my real cat/ hangover/ bad hair) with the syntactically awkward, machinic language, which undermines any notion that this diary is the expression of any authentic subject.

The demanding aspect of it is something I was interested in too, since it calls up the notion of endurance as a virtue, and therefore as a value-enhancer, which many artworks – from mind-boggingly labour intensive supercut-style videos to sculptures made from millions of pins (or whatever) – trade on. You just can’t help but ask ‘wow…how long did that take?!’ – as if the time, labour and effort, i.e. the endurance, necessarily confer value. So there is a parallel between a certain kind of ‘age of austerity’ rhetoric that valorises resilience and endurance and artworks that trade on a similar kind of doggedness – like Life in AdWords does.

And finally – it made me laugh. Some of the text was so dumb, and funny, it amused me to think of these algorithms dutifully labouring away to come up with key-phrases like ‘Yo Mamma jokes’ and ‘weird pants’.

MG: It ran until 20th January 2013, and ended due to system changes in the Gmail ad settings. How many videos did you produce and were you glad when it all had finally ended?

ES: Not sure how many I made – but I was 6 weeks short of the intended year, so definitely over 300. Actually I was infuriated and somewhat depressed when it ended without warning and in a moment of panic I even thought about somehow cheating it out to the end; but working with a system that is beyond your control (i.e. Google) necessarily involves handing over some of your authorial agency. So instead I embraced the unexpected ending and threw a kind of send-off party plus performance in my bedroom/ studio to mark it.

But this question of agency is obviously crucial in the discussion of technology and runs through the project in various ways, beyond its unintended termination. At the level of the overall structure, it involves following a simple instruction (to write and process the diaries every day and do the webcam recording) which could be seen as the enactment of a procedure that echoes the operation of a software program carrying out automated scripts. And on the level of the texts, while all the language used in the project was generated and created by the software, I also was exercising a certain amount of control over which sections of the diary I favoured and editing the resulting lists, a move which seemingly reasserts my own authorial agency.

Thus the texts are more composed and manipulated than they first appear, but of course the viewer has no way of knowing what was edited out and why; they have to take it on faith that the texts they hear are the ‘real’ ones for that diary.

MG: During this period you recorded daily interactions of the ongoing experience onto webcam. As you went through the process of viewing the constant Google algorithms, I am wondering what kind of effect it had on your state of mind as you directly experienced thousands of different brands being promoted whilst handing over the content once again, verbally to the live camera?

ES: I’m not sure what effect it had on my state of mind, though considering the amount of concerned friends that got in touch after viewing the videos, Google certainly thought I was mostly stressed, anxious and depressed. Maybe it’s just easier to market things to a negative mind state.

But also, the recurrence of these terms was no coincidence; early film theorist Tom Gunning has argued that Charlie Chaplin’s bodily movement in Modern Times [5] ‘makes it clear that the modern body is one subject to nervous breakdown when the efficiency demanded of it fails,’ and compares his jerky, mechanical gestures with the machines of his era.

So I was interested in if and how you could do something similar for the contemporary body; how can we envisage it and its efficiency failures in relation to the technology of today when our machines are opaque and unreadable, if we can see them at all. Maybe what they ‘look like’ is code (a type of language), so it would entail some kind of breakdown communicated through language rather than bodily gestures – though the deadpan delivery certainly evokes a machinic ‘computer says no’ type of affectlessness.

Also, Franco Berardi has spoken of the super-speedy fatigued denizen of today’s infoworld, for whom “acceleration is the beginning of panic and panic is the beginning of depression”. In a sense this recurrent theme of stress and anxiety disavows the idea of the efficient, ever-ready, always-on subject of neo-liberalism – and yet the project as a whole kind of sneakily joins the club too, since it obeys the imperative of productivity by turning a diary (personal life, non-work) into a ‘project’ (i.e. work).

As mentioned earlier in terms of the ‘transformation economy’, I’m really interested in this idea of efficiency also as it manifests in rhetorics of self-betterment, and its relation to the neo-liberal promotion of self-responsibility (if you’re poor, it’s your fault….). Diaries and journal writing – as well as meditation, yoga, therapy, self-help etc – are often championed in everything from cognitive fitness to management literature as excellent ways of becoming more ‘efficient’. The underlying belief seems to be that by unloading all the crap that weighs you down, from emotional blockages to unhelpful romantic attachments to an overly-busy mind, you’d get an ‘optimised you’. Why this is necessarily a good thing – apart from the elusive promise of ‘happiness’ of course – is never really discussed.

Tiqquun’s notion of the Young Girl, the model consumer-citizen, is interesting in this regard – taking good care of oneself reframed as a form of subservience which maintains the value and usefulness of our bodies and minds to capital. Their idea that the Young Girl (not actually a gendered concept in their estimation) “advances like a living engine, directed by, and directing herself toward the Spectacle” also points to the irony beneath what appears to be a very humanist/ individualist inflection to these discourses of self-realisation: they could also be read as a latent desire to become somehow more ‘machine-like’, as if we could therapise/ meditate/ journal/ jog away our mind-junk with the swiftness and ease of emptying the computer’s trash, thereby becoming more productive.

And yet I’m clearly complicit in this, as I write diaries, meditate, do yoga and obsess over my bad time management, as Life in AdWords makes clear both in the recurrence of all these activities in the texts and obviously in its structure as a daily journal project.

MG: Robert Jackson in his article Algorithms and Control discusses in his conclusion that even though “use of dominant representations to control and exploit the energies of a population is, of course, nothing new”, when masses of people respond and say yes to this “particular reduced/reductive version of reality”, as an act of investment it “is the first step in a loss of autonomy and an abdication of what I would posit is a human obligation to retain a higher degree of idiosyncratic self-developed world-view.” Alex Galloway also explores this issue in his book Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization, where he argues that the Internet is riddled with controls and that what Foucault termed as “political technologies” as well as his concepts around biopower and biopolitics are significant.

Life in AdWords, seems to express the above contexts with a personal approach on the matter. Drawing upon an artistic narrative as the audience views your gradual decline into boredom and feelings of banality. The viewer can relate to these conditions and perhaps ask themselves similar questions as they go through the similar experiences. Thus, through performance and a play on personal sacrifice on a human level, it elucidates the frustrations on the constant, noise and domination of these protocols and algorithms and how they may effect our behaviours.

With this in mind, what have you learnt from your own experience, and how do you see others regaining some form of conscious independence from this state of sublimation?

ES: I found Galloways’ explanation of Foucault’s notions of biopower to be some of the most interesting parts of that book – as he puts it “demographics and user statistics are more important than real names and real identities”, so it’s not ‘you’ according to your Amazon purchase history, but more ‘you’ according to Amazon’s ‘suggestions’ (often scarily accurate in my experience). Which is where the algorithms come in; they do the number-crunching to be able to predict what you might buy, and hence who you are, not because anyone cares about you particularly, but because where you fit in a demographic (a person who is interested in art, technology, etc..) is useful information and creates new possibilities for control.

Regaining conscious independence… hmm. I found it interesting that during the project, the people I explained it to would often report back to me on what keywords their emails had produced, and what adverts came up on Facebook, as they hadn’t really noticed before – so perhaps in these cases it made people more conscious of the exchange taking place in the ‘free’ web economy. Others took up AdBlocker in response, which is one way of gaining distance – by opting out. However, the info each of us generates is still useful, since even if you aren’t seeing the ads, your choices and interactions are still being parsed and thus help delineate a particular user group of citizen-consumers.

Despite this, my feeling is that opting out – if it’s even possible – can be a way of pretending none of this stuff is happening. I’m generally more interested in finding ways of working with the logic of the system, in this case the use of algorithms to sell things back to us, and making it overly obvious or visible. Geert Lovink asked whether its possible for artists to adopt an “amoral position and see control as an environment one can navigate through instead of merely condemn it as a tool in the hands of authorities” and his suggestion of using Google to do the ‘work’ of dissemination for you, in spreading your meme/ word/ image, is one I’ve thought about, particularly in other works (especially Woman Nature Alone). This approach entails hijacking the process by which Google’s algorithms organise the hierarchy of visibility to one’s own ends – a ‘natural language’ hack, as Lovink puts it.

In contrast, Life in AdWords makes visible the working of the algorithmic system more on the level of the language it produces. It also employs humour, and laughter has been one of the main responses people have had when watching the videos, for a number of reasons. The frequent dumbness of the language and/ or the juxtapositions (‘Where is God?’, ‘Eating Disorder Program’); the flattening out of all difference between objects/ feelings/ places (e.g. work-related stress, cat food, God, Krakow); and the lack of shame the software exhibits in enumerating bodily and mental malfunctions (blood in poop, wet bed, fear of vomiting) are all quite amusing in and of themselves.

That shameless aspect also echoes the over-sharing and ‘too much information’ tendencies the web (especially social media) seems to encourage, which Rob Horning has written about in his excellent blog, Marginal Utility. It also foregrounds that whatever the algorithms can do, what they still can’t do is emulate the codes of behaviour governing human interaction – including knowing when to shut up about your ‘issues’.

The frequent allusions to these bodily and mental blockages also point to the limits of the productivity imperative – a refusal to perform enacted through minor breakdowns – while bringing it back to an embodied subject, who despite her immersion in networked space is still a body with messy, inefficient feelings, needs and urges. And the comically limited portrait the keywords paint maybe suggests that despite the best efforts of Web 2.0 companies, we still are not quite reducible to a list of consumer preferences and lifestyles.

MG: What are you up to at the monment?

ES: Amongst other things I’m doing a residency with Field Broadcast (artists Rebecca Birch and Rob Smith) called Domestic Pursuits, a project which ‘considers the domestic contexts of broadcast reception and the infrastructure that enables its transmission.’

And I’m working on some drawings plus a video involving Skype meditation with members of the Insight Timer meditation app community, for A Small Hiccup, curated by George Vasey and opening 24th May at Grand Union, Birmingham- the video is being shown online tommorrow.

Also I’m attempting and mostly failing at the moment to write my dissertation for the MRes in Moving Image Art I’m doing at Central St Martins and LUX.

Personal Web searching in the age of semantic capitalism: Diagnosing the mechanisms of personalisation. Martin Feuz, Matthew Fuller, and Felix Stalder.

http://firstmonday.org/article/view/3344/2766

Live Performance. KONRAD BECKER (aka Monoton) featuring SELA 3 themes from “OPERATIONS” (15 min.). Published on Jul 9, 2012. YouTube.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMscYTAF4wY

Erica Scourti was born in Athens, Greece in 1980 and now lives in London. After a year studying Chemistry at UCL, an art and fashion foundation and a year of Fine Art Textiles at Goldsmiths, she completed her BA in Fine Art at Middlesex University in 2003 and is currently enrolled on a Research degree (Masters) in Moving Image Art at Central Saint Martin’s College of Art & Design, run in conjunction with LUX. Her area of research is the figure of the female fool in performative video works.

She works with video, drawing and text, and her work has been screened internationally at museums like the Museo Reine Sofia, Kunstmuseum Bonn and Jeu de Paume Museum, as well as festivals such as the Recontres Internationales, interfilm Berlin, ZEBRA Film Festival, Antimatter, Impakt, MediaArt Friesland, 700IS as well as extensively in the UK, where she won Best Video at Radical Reels Film Competition; recent screenings include Video Salon Art Prize, Exeter Phoenix, Bureau Gallery, Tyneside Cinema and Sheffield Fringe Festival.

Her work has also been published in anthologies of moving image work like Best of Purescreen (vols 1, 2 and 3) and The Centre of Attention Biannual magazine.

more info – http://www.ericascourti.com/art_pages/biography.html