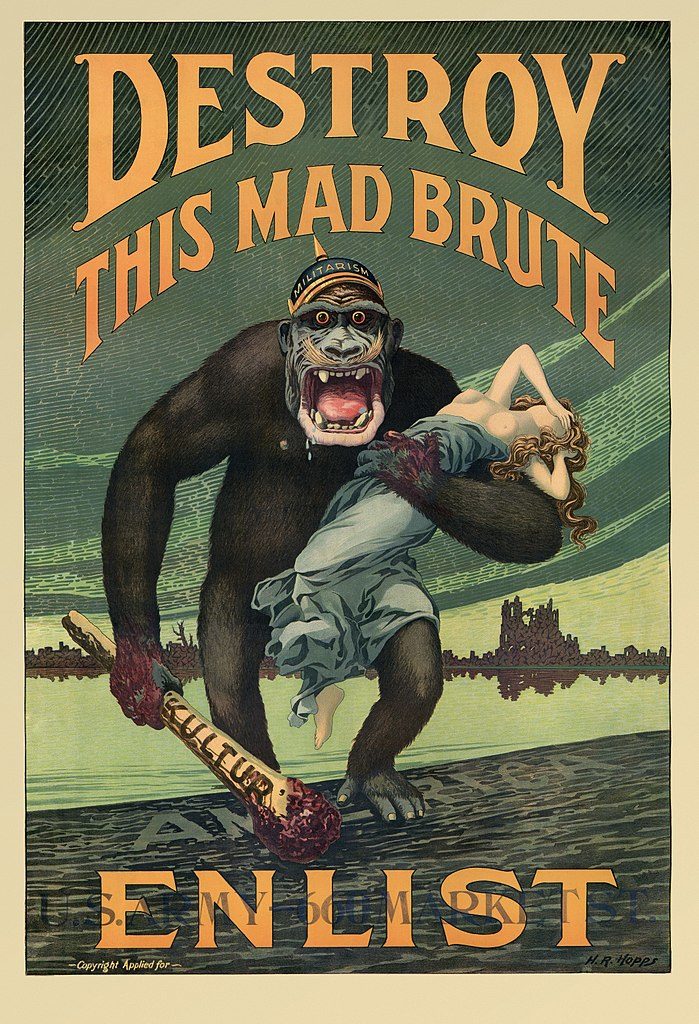

Featured image: Donald Trump as a God

“There I was faced with my nemesis, reading. It isn’t that I flubbed the words, or stumbled and mispronounced; I even placed the emphasis on the right syllable. I just lack personality when I read. The second day I was introduced to the rushes. This is the custom of going at the end of each day’s work and seeing on the screen what you shot the previous day. What a shock it was!”

-Ronald Reagan in 1937

Donald Trump has a face moulded from a slowly drooping wall of pitch. The languorous slump of his chin is accentuated by a zealous orange complexion and hi-definition makeup creases—his physiognomy would be an intricate though grotesque addition to the faces scarring the side of Mount Rushmore. Topographically speaking though, his jib is markedly less stately than Lincoln’s staunch jaw: the line from The Donald’s chin-to-neck sloping lazily in a curve that flaps and wobbles with the exaggerated gymnastics of his puckering-unpuckering mouth.

Trump’s iconic visage has dominated the memeplex for months, corrupting our newsfeeds with bust-like portraits of a man whose Tang-coloured tanning cream has since inspired a litany of derogatory epithets. Yet one of the remarkable characteristics of his campaign and its corresponding media coverage was how effortlessly both so-called mainstream media and internet culture latched on to Trump’s face as a cultural and political meme.

We can see the reproduction of iconographic power at work with a brief review of the 2016 election cycle. While campaigning for his ascensions to the Presidency, news networks depicted Trump’s head as visually emancipated from the fleshly anchor of his body, utilizing a close-cropped frame as a political device to craft caricatures by leveraging his most noticeable features—a lumpy chin, puckered mouth, wispy hairpiece. Here we see the head of God-Emperor Trump. Trump’s profile an image figurative of the head of state, the corporeal body transformed into the body politic that is an icono-graphy ready for reproduction and primed for cross-pollination with the memeplex. In fact, images of Trump’s face were so abundant during the lead-up to the election that an ur-typology of Trump media began to crystallize as campaign season progressed: Trump, face isolated, with hair-piece captured in striking relief against a backdrop of blurry patriotic signifiers. (The vertiginous swoop of sallow hair and recumbent double chin looms as pervasive and recognizable as the gaminesque contours of a perverse Pixar character in profile.)

Trump entered the 2016 race with decades of brand-management experience: his reality TV presence cemented the immediate recognisability of the TRUMP trademark, endowing his face with the universality and divine potency normally associated with the glittering icons of Byzantine Christianity. So, I wonder what Trump thinks when he looks in the mirror—he does not seem to grapple with contemplating himself in the eyes of others, as the professional actor-cum-president Reagan did, enshrining his Presidential role as the ultimate piece of character acting, fraught with tortured considerations about the role of self-image, self-perception and the externalization of the indexical viewpoint of the acting eye. Reagan was concerned with how others perceived him, as Trump is. But Trump is a businessman and seems to outsource concern for his image, treating it as a theatrical production supported by the labour of an elaborate team of technicians, brand-managers, lawyers, make-up artists, photographers…As an actor, however, Reagan was fastidious about contemplating his own performance, making and remaking himself to suit his own ever-changing, idealized self, performing his image as he wanted others to see it.

***

The most recent internet exhibition from the German collective UBERMORGEN continues the obsession with Trump’s visage in an online exhibition recently hosted by London gallery Carroll / Fletcher, which features the faces of Donald Trump and Melania Trump rendered in .gif format and created by UBERMORGEN, the Swiss-Austrian-American duo consisting of lizvlx and Hans Bernhard. Their recent work, Neue Ehrlichkeit (trans. “New Honesty”) contains two gifs: one of Trump and one of Melania, the frame cropped so close to their faces that you can see Trump’s ear piece and discern the mascara clumps adhering to Melania’s eyelashes. The gifs move manically, flipping over the y axis, invisibly bisecting the frame at vertigo-inducing speed. As you continue to watch the gif flicker, it seems to accelerate uncontrollably even though the timing of the gif loop is unvarying. Combined with the drooping jowls and brillo-pad eyebrows of Trump – details that linger for a static nanosecond in the mind’s eye – the effect is even nauseating.

UBERMORGEN preface this recent work with the following exclamation:

“The post-factual world is not a new phenomenon, not at all! But I love that the world has finally come to an agreement and I love the idea that there are so many others consensually hallucinating with us in understanding the fact that we are part of a post-factual world without ever having been in a factual world.” UBERMORGEN, Truth-Tellers Conference, Berlin, 2016

The “fact that we are part of a post-factual world” is a resolvable contradiction – UBERMORGEN’s idea of “new honesty” in a nutshell. The new honesty of post-factuality expresses anxieties about the transformations brought forward by digital technologies, but seems to (incorrectly) cite the internet as the culprit causing the erosion of trust in utterances made both off and online. (And if we learned anything from continental philosophy’s critique of empiricism, it’s that empiricism as an epistemic framework places truth and falsehood on the same fragile fulcrum, separated only by a collective delusion known as “evidence.”) One kind of post-factual phenomenon, fakeness, seems to elicit particularly virulent and hysterical reactions. Fakeness feeds on the production of virality. Fake news flourishes not only because of the viral networks that seed, transmit, and accelerate its reproduction across the social media platforms and carefully cultivated echo chambers of the web, but because fakeness marvels at the speed of its own-reproduction. Fakeness is a narcissistic vortex; it is the viral subject celebrating its own hysterical recirculation, thriving on the spectacles of hysteria and disbelief that it stokes to fuel its continued seeding of newsfeeds.

Trump’s face is a fake, a simulacrum of a face—caked in makeup, sweating under the bright bulbs of cameras, and creased with the lines of fake-tan fissures, the surface of his skin looks like an aerial photograph of the Sahara during sunset. His face is there, but it isn’t real: it operates on the level of the Imaginary. On a Zizekian interpretation of Lacanian epistemology, this is to say: Trump’s carefully curated, commodified image is a simulation, but a simulation that occupies a position of so much power that the image’s artificiality is (im)material. T R U M P the copyright, trademarked, licensed image is more real than the man himself. And, like “fakenews”, Trump has a vested commercial and now political interest in circulating his image, spreading his brand and colonizing new territories of financial opportunity that leverage and license the attention that the TRUMP exploits for profit.

***

Even though the obsession with The Donald’s face has not abated (reverberating duh), the relationship between Trump’s body and the media-memeplex dyad is quite different. Photographs of Trump that expand the optical frame to encompass his whole body portray him as a lumpy bundle of poorly tailored suits, wrinkled folds, and a protruding mass of flesh hoisted around his middle. Despite his wealth, status, and power, Trump owns a body much like that of middle-America, although his constituents are nourished on government subsidies of high-fructose corn syrup, fast food, and snakeoil dietary fads rendered (unsurprisingly) unsuccessful, rather than Mar-A-Lago brunches and Trump Tower hamburgers. Still, Trump looks as fit as the average American; his physique psychically resonates with his supporters and functions as the punctuation mark to the fanatical authoritarian-pseudo-populism of his speeches: Look! his round-shouldered posture and huddled gut proclaims: I look just like you! Vote for this body! Admittedly, Trump’s physique is not a new object of scrutiny: reflecting on the apocalyptic Presidential Portrait produced by Jonathan Horowtiz, Jerry Saltz remarks that Trump is:

“…strange, always swathed in a lot of clothes, large but unformed, awkward because he has no clear shape or outline.”

In Parables for the Virtual, Brian Massumi elaborates on the affective valences of the body as image and body without image. Body-without-image is the corruption of the normative way that bodies are produced and how they generate affective frequencies in relation to the connections and fissures that form between other bodies. The body-without-image is an aberrant figure for Massumi, which he describes as occurring when “Subject, object, and their successive emplacements in empirical space are subtracted, leaving the pure relationality of process.” (68)

If we try to image Trump in all his fleshiness, it becomes difficult. Trump the man has “no clear shape or outline”, and our collective Imagination staggers and stumbles as we try to map the boundary-lines of this man. (We might, perhaps, find it easy to caricature his “tiny hands”, but how much of our hallucination is rendered accurately, and how much of it is reposing on citing the hysteria of a tiny hands-meme for artistic direction?) If someone says TRUMP, it’s his face that we imagine, not his physique.

Further along in Parables of the Virtual, Massumi rigorously plumbs the affective resonances of the bleed, the planes where the virtual and the real intersect and erupt into productions of affect. To seriously consider the interstitial spaces where the hallmarks of reality and the virtual co-exist in neurotic states of indeterminacy requires rethinking what it would mean to give a logical consistency to the in-between. On Massumi’s view, the logic of the in-between demands:

“realigning with a logic of relation. For the in-between, as such, is not a middling being but rather the being of the middle-the being of a relation. A positioned being, central, middling, or marginal, is a term of a relation.” (70)

Another, though narrow, way of framing the need for a new logic of the in-between is to call for a radically recalibrated understanding of the “middle class” and its interposition. To whom is it designed to relate, for what ends, and by which design? If the middle class is a “positioned being, central, middling, or marginal” as Massumi argues, then it must also be seeking a reconciliation with one of the poles that bookends this relation. It is drawn towards stabilization, which is another way of saying that is oscillates unevenly, polarizing the relationships on either side. It migrates towards Trump, whose words and gestures – and physique – are like a magnet. According to the deluge of thinkpieces on Trump supporters that were churned out following the election, we know that middle-America thinks Trump is “just like us”. And we know another axiom: like attracts like.

But if Trump’s body looks like the “middle-class”, it is also a kind of hallucination—Trump’s body is the product of a lifestyle of luxurious, conspicuous excess. Any similarities are accidental, since Trump has never been in the position of foregoing diabetes medication due to rising medication prices; has never had to settle for junk food while living in an economically depressed food desert littered with high fat, high salt, edible detritus; he does not know what it is like to stitch up his own lacerated hand because the thought of incurring several thousand dollars in Emergency Room bills might provoke yet another psychic and physical trauma. In a way, Trump is not a body-without image, but image-without-body.

Here we have arrived at a key oxymoron of Trump: he is fake body attached to a simulated image.

His image is an incarnation that desires its own reproduction. It is the simulation of a man, the materialization of a God-Emperor, the embodiment of the TRUMP brand. Trump’s visage is that Paterfamilial image spiralling towards its historic manifestation, driven by a self-replication that can impregnate the memeplex with his iconographic face and drive more and more money towards the TRUMP Empire.

But Trump is also a grotesquely physical body, one that has used the powers its girth commands to physically assault women or wrestle awkward handshakes out of self-assured world-leaders. Even that, though, is a kind of hallucination: in our collective media-conscious, Trump’s body offers itself up as fodder for the refashioning of the flesh in the image of the Great American Hero, the hard-working, downtrodden, blue-collar, temporarily-embarrassed millionaire man—one who is always being dragged out of the dustbin of history, resurrected to reassure us that the America Dream can speak to us, too, if we hallucinate hard enough.

In recent times we have often heard that we’re facing the end of the world as we know it because of factors such as potential nuclear wars, self-sufficient machines, international political crises, and global environmental disaster. However, people in every single age have believed they were heading towards the end of the world. The feeling of being trapped at the end of a road leading nowhere is crucial to understanding why we have needed to apply definitions such as “post-truth” and “alternative facts” to centuries-old rhetorical strategies – creating new terms for the last age of humankind as we know it.

Whilst it may be true that propaganda has been strategically important in shaping opinions since King Darius, the nature of media – from cinematic newsreels created by 1910s national bureaus to today’s social media landscape – plays a crucial role in shaping how strategic messages are created and disseminated. Although we have shifted from the broadcast model of the 20th Century to a mode of prosumption, we are still dealing with the same questions: what effective power does language have? When does a message become propaganda? To what degree can individuals be defined as passive (or active) agents when they share officially approved information? Given these questions, it is no surprise that a number of contemporary artists working with the internet and digital cultures are responding to a perceived crisis of “truthiness” with strategies deriving from the 1910s activity of the Dadaists, a cultural elite who worked in Europe and the U.S. in war times.

Since the 1980s, early artists working with the internet claimed a connection between online art and Dada. It is now important to consider the reasons why, more than two decades later, new generations are still playing in the same field discovered by the Dadaists. The first Dada group was founded in 1915 in Zurich, one of the safest places in Europe, by artists and poets who could afford the journey and the stay. In such a city, anything could be said and written without caring too much about the actual consequences. Broadly speaking, this perceived freedom of expression is analogous to the promises of today’s social media, where everyone purportedly has the same right to share opinions and get involved in discussions as everyone else, without feeling obliged to be politically correct. A sense of detachment is among the features shared by the original Dadaists and contemporary artists with an interest in political questions. Often working in isolated environments, today’s artists use detachment as a strategy by distancing themselves from what’s happening behind the borders and commenting on the daily news, attending to how ‘facts’ have been narrated rather the ‘facts’ themselves.

Another important feature shared both by contemporary artists and the Dadaists is a focus on the ‘flatness’ of communication, which was adopted in strategies of advertising, propaganda and manifesti. This flatness arises since every sentence is an exclamation and the reader’s attention is diverted by unexpected changes and incessant slogans, making the message a discourse without hierarchies. This mechanism makes every part important and urgent, such that, no one part is actually necessary for the economy of the message.

A century ago, a political or artistic group couldn’t be defined as such if it didn’t publish at least a founding manifestoin a newspaper. To write a manifesto meant to impose a vision of the world, to claim the priority of some values in respect to other interpretations. Nowadays people rarely make manifesti, but a spectacular exception is Google’s list of guidelines for Material Design. These aim to spread the word about a “unified system that combines theory, resources, and tools for crafting digital experiences”, a mission recalling those stated by avant-garde and modernist groups to rebuild the world according to a unifying principle embracing all aspects of human beings. Artist Luca Leggero followed the guidelines provided by Google to make #MaterialArt (2017), colourful plastic art sculptures challenging the definitions of artwork and design pieces. Leggero critiques Google’s objective to reconstruct reality under its terms by putting into practice an accelerationist strategy; if everything must become part of the Google-branded world, why not art?

In the 1910s, groups published as many manifesti as possible in order to maintain interest among the public.4 To respond to their dogmatic and flat communication mode, however, Dadaists created countless statements that were not linked with each other whatsoever. For the Zurich group, the goal was to generate noise in the endless stream of commercial and political propaganda; it was a joyful activity that, with its randomness, confirmed the nonsense of all the other official communications. Today, the production of noise, and the disruption of corporate and political communication platforms is the aim of many artists’ practices, but only a few of them are so incisive as Ben Grosser’s. “ScareMail” (2013) is a web browser extension that originated in the midst of the 2013 NSA surveillance scandal. For every new email, it adds an algorithmically generated narrative comprising terms that would likely ring an alarm bell at the NSA.

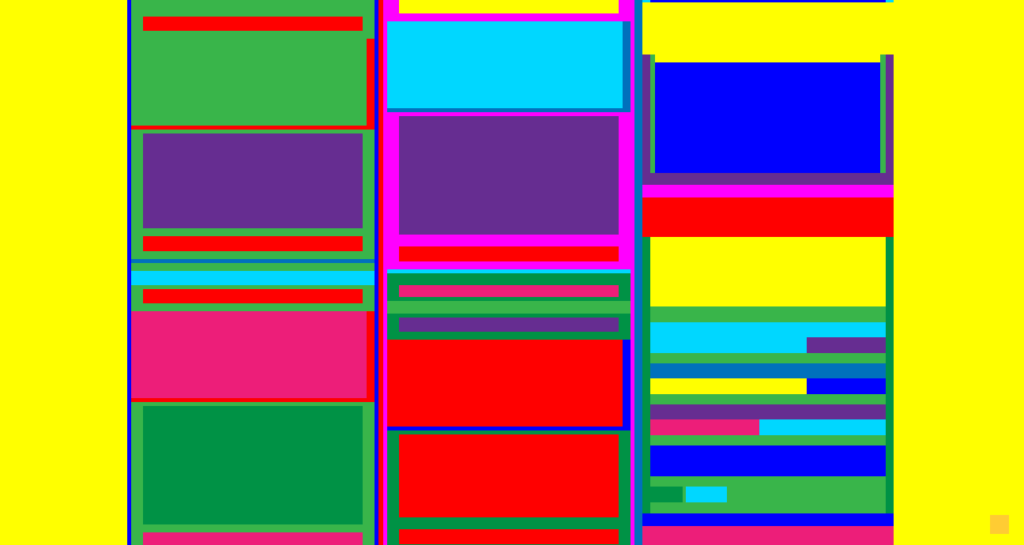

Given the importance of ‘flat’ communicative hierarchies in Dada practice, it’s not surprising how many Dada artists studied the concepts of randomness and entropy as a way of making new realities. There is not just one reality, they seemed to claim, but too many to even imagine; there is not just one imposing point of view, but many – and these may not concur with each other. An exemplary case is a series of collages by Hans Arp arranged according to the Laws of Chance, which didn’t mean they were made without the exercise of any control, but that the artist arranged the pieces automatically, by will. An interest in automatism can be found in many contemporary artists using algorithms as artistic tools, such as Rafaël Rozendaal with Abstract Browsing (2014), a Chrome extension that turns any website into a colourful composition. HTML is a language and as such, it can be read by the browser in many ways, not only the one used by developers and designers. Rozendaal’s work shows the random potential innate in anything, while suggesting there are alternative ways to consume given contents.

“Abstract Browsing” (2014), Rafaël Rozendaal

The production of noise seems to have been the most disruptive response to nationalist propaganda and corporate advertising produced by the original Dada groups. Most of these artists challenged the dogmatic, exclamatory tone used in the official language of war bulletins and newspaper adverts. Taking advantage of this tone and using it in chance-driven messages allowed them to reveal the absurdity of the dogmatic nature of propaganda and advertising.

Many contemporary artists are more or less consciously keeping alive these practices and producing their own kinds of noise in the face of fake news and alternative facts. Nowadays, not only do governments and advertising companies subtly practice dogmatic and exclamatory strategies, but it is even taken for granted they can and indeed do put into practice such disruptive ways to spread messages. When propaganda exploits guerilla strategies, and is generated in the same way art projects disrupt media environments, how should artists respond? This is one of the most challenging issues some artists want to address and the next few years will be a rich (and noisy) testing ground for many of them.

Structures. Something has been built, grown, stretched. Maybe skin, maybe a web, maybe a protective barrier – it is a plastic protein emitted by an organism in order to increase its survival opportunities, it is a food matrix for its offspring which thrive on glossy resin. You can travel across it and it can easily be mapped, although not by humans.

We can’t say anything about it – we can speculate everything about it. It is something possible or as the author says another reality. The real is replaced by the potential. This is one of a series of works by St. Petersburg-based artist Elena Romenkova. The works are glitches, abstract distortions, alien expressions of what for her is a subconscious realm.

A portal. You are entering the rainbow world contained within two concentric eggs within the grey world. This is light, reflections, haze, indescription. It looks inviting. The colour spectrum is odd, the whites creep up on everything else, the shape of everything is strange. Basic synaesthetic rules are inapplicable at the rainbow/grey world junction.

There is nothing that this image, by French artist Francoise Apter (Ellectra Radikal), has in common with Romenkova’s. They are united only by their adherence to strangeness, a technically created vista that looks like nothing we know. A world not of local cultures, but of computational production. Here anyone can know anything, it doesn’t matter where you’re from.

What is culture when locality is secondary to epistemology? What is knowledge when the portable device takes precedent over your situated environment? Worlds are built around us, sophisticated electrical spaces, they travel where we travel, and only after do we factor in the idiosyncracies of specific geography. If the banal experience is one of nomadic alienation, of search methods based on no place, what does the role of culture and art become? Everyday life is a subject for hypothetical language. The digital commons is a species of posthuman that communicates via speculative misunderstanding.

Korean artist Minhyun Cho (mentalcrusher) shows us what the dinosaurs really looked like. When you put the meat and scales back on. He shows us what an ice building being looks like in the shadow of terminal cartoon winter. How rubber can be used to erect sculptures and bones can be taken out of museums and put to good use in civic architecture. No one is around to see this, but still the idea sets a precedent. Crown each ghost with ice mountain prisms.

With visual language, very quickly we get to a stranger and more indeterminate range of science fiction possibilities than narrative tends to map out for us. How much imagination is possible, and how much does our internal experience match anything presented around us. If our environments advance exponentially quicker than any generational or traditional mythology, what sort of language can we have for expression? The maker’s invention precedes the reception of form. Innovation is a matter of banal activity, communicating an experience of the real which is never the same.

And now an eyeball. Triangles. A vessel. To Cho’s blinding world of light, Spanish artist Leticia Sampedro responds with a featureless darkness. All absurdities once on display, now they recede into nothing. It might be a mandala, perhaps an artifact from the ancient future, a portable panopticon that fits conveniently on your desktop. Your feelings are here, your peculiar distances, everything’s reflecting off the glass, the metal, the camera. You are the mirrored fragments of an invention we’ve lost the blueprints to. Foresight the womb of a disembodied politics of community.

Community held together by structures. In German artist Silke Kuhar‘s (ZIL) work, we enter into one of these structures. Inside we find hallways, a nice selection of windows and all kinds of data – scripted, graphed, symbolized. This is the plan for the future. I hope you can read what it says. Her work meshes spaces with collapsing foreign constructs – if we can just read the language we’ll know what to do. But no one reads it, and no one wrote it. This is a building without inhabitants – architecture without people. Democratic ballots are automatically filled out by a predetermined algorithm. Your agency is a speculative proposition for popular media – people collaborate with you, but they can’t be sure where you are, when you wrote, and if you really exist as such.

No people. This is a unifying principle. Cold, silver, streams. Machines in the sky. Silicon waterfalls, diagonal. Civilization distilled into physical patterns, an obtuse object photographed in another dimension. What is the word for reality again. What is the word for scientific investigation? A Venezuelan based in Paris, Maggy Almao’s abstract glitch world is silent – it’s a gradient, it’s some illusion of partial perspective.

What is the language to talk about the world? If we turn to artists’ visualizations, what does that tell us about languages we speak, and ones we read? What does the graphing of incomprehensible mechanisms tell us in turn about art and its history? The machine’s narratives tend to drown out any functional reality. Genre storytelling tropes become repurposed as collective cultural ideas. Conceptual works are followed by pragmatic speculation, medium-centric analysis replaced by experimental failures. You can never get a fictional experiment to work.

Science has indelibly entered the art field, for each of its medial innovations it requires further attention in terms of its technical makeup. Half the work is figuring out what the canvas even is, we are building canvases, none of them look alike, and their stories read like data manuals. An aesthetics of unknown information.

This is the homeland. The homeland is mobile and has many purple bubbles. It’s an airship from the blob version of the Final Fantasy series. It has satellite TV to keep in touch with the world. It has some tall buildings so you know it’s civilized. It is part of Giselle Zatonyl, an Argentine-born Brooklyn-based artist’s opus which deals comprehensively with science fiction ideas and their implications.

The ship travels, where the culture originates is more and more unknown. It is technically divided, access is the key, we can worry about language and culture later. We are still embodied, still located somewhere, but all this has become subject to the trampling of scientific mythologies, where their utilities might go, and where their toys are most needed. Crisis is a genre now, about as popular as time travel. You are now free to dream up whatever future society you wish, and subjugate whatever cyborg proletariat your heart desires. In the realm of speculation, anything is possible, and nothing is fully acceptable.

The themes of internet art production give us some language, some set of visions that tell certain stories – works found throughout the internet, posted in communities, shared online – sometimes part of gallery exhibitions or products, sometimes not. You get a profile, some social media pages, build a website, you begin making, sharing and remixing images. Folk art is a subsidiary of new media art – social sculpture meets internet content management systems. A language for political engagement based on the creative activity of speculation. Scientific dreams for a technological commons.

Dreams where sight is physicalized into complex data graphs. Where Sampedro’s portable gelatin panopticon is cloned into a regularized matrix. Inspired vision is just one aspect of algorithmic predictability. In Taiwanese artist Lidia Pluchinotta‘s visual work, the cloned image is central. Mechanical reproduction, skulls, spirals, symbols, the internet has it all. Civic participation has never been so mathematical, observation never so multiple.

Inside the city, architecture is actually a colour-coded map that helps you find the store you’re looking for. The map is the territory except there’s no info on how to read it. We are here, we are home, but the walls of the buildings were designed by some specialist that we haven’t met yet. Stairs, depths, the complex and layered constructions in Canadian artist Carrie Gates‘ work aren’t quite one of Zatonyl’s buildings. More fragmented, more saturated, more chaotic. It’s speculated that people could live here, although we don’t see them anywhere. Not yet anyway.

The maelstrom of technological progress presents us with the need to adapt our participation and rhetoric accordingly. Science fiction is a folk language for common experience within a technoscientifically oriented world. These images are imaginative products of social and participatory artist communities who, when marrying the personal and contextual, create speculative objects of general strangeness. Their description is nothing less that one of alien entities – alien entities that are everywhere. Earth is the most sophisticated foreign planet we’ve yet to invent, we just need to discover how to populate it.

Glitch as an aesthetic signifier of technological presence dates back at least to the 1980s. Look at The Vaught-Kampf machine in Blade Runner (1982) or the titular character in Max Headroom (1985). The use of Glitch as an artistic aesthetic in itself has accelerated with the democratization of newer technologies that make older glitch-prone technology obsolete. When a technology becomes redundant, its previous technical inefficiencies become available for aesthetic recuperation and appreciation.

The hiss and crackle of vinyl records, to be ignored or reduced as far as possible by the mid-20th century audiophile, became signifiers of historical authenticity in 1990s Trip Hop. The lens flare, light seepage and colour shift of cheap mass-produced chemical film-based cameras have been turned from annoyances to fetishes with Lomography (experimental analogue film photography) and Instagram. And the glitches of poor video connections or corrupted floppy disks have followed a similar path in Glitch art.

This is a process of ironisation. Irony changes or inverts content without altering form. Meaning is introduced into systems by ironising non-signifying forms. It is modified and modulated by further ironising those forms. The glitches that once frustrated media professionals and home users of electronic media are ironised into aesthetic form in Glitch Art.

Glitch Art sits in the historical tradition of process art and chance art. Automatism and chance acts in Dada, Surrealism, Situationism and the Oulipo, and Scatter art. Generative and algorithmic art. Action painting provides the useful concept of “all-over composition” as a way of avoiding a requirement of specific, localisable intent in aesthetically, evaluating an image.

Glitch art also sits in the historical traditions of remix art, detournement and décollage. The knowledge that the image has been altered is key to its aesthetic reception. It’s tempting to talk about the creative destruction of capitalism and to damn Glitch as neoliberal apologia, but that’s too easy and would leave the speaker too comfortable. It is also very tempting to try and place Glitch Art within the traditions of anti-aesthetics or of nominalistic/found art, or to compare the use of image corruption to artistic outsourcing or crowdsourcing in terms of artistic abrogation of authorship. But Glitch is at least curated by the artist, and its generation requires an engagement with the specificities of digital media that they are not supposed to have. The Glitch artist is artisan, not manager, and Glitch Art is sublime, not ordeal.

Panofsky’s extension of the idea of symbolic form to perspective can be applied to Glitch as form. Glitch is effect (a body of effects) that generates *critical* form. The patterns of noise or confounding signals that result from analog or digital image corruption and the effects on displaced sections of the corrupted image are form, presented for positive aesthetic evaluation rather than removed to avoid negative technical evaluation. This complicates Shannon’s diagram of information transmission. Noise is ironised into signal.

The smooth running of inhuman systems is disquieting. Glitch reasserts their materiality. To the extent that it did so to generalise specific failings to a general system in order to make them appear fallible and human this would be kitsch. To the extent that it did so to remind us of older technology, it would be Cory Arcangel-style leveraged nostalgia. And to the extent that it generationally positioned itself against the previous generation’s perception of value in its own culture would be adolescent, social positioning.

Glitch art avoids these failings by producing tension and contradiction rather than jouissance and confirmation. It is disquieting in a way that disturbs the new without allowing a return to an idealized earlier social and aesthetic order, and it is aesthetically creative in a way that does not hide the destruction involved.

The 8 and 16-bit console software beloved by some Glitch artists is comprehensible to them and to their audiences in a way that 64-bit cloud-based network software is not. The former is therefore a useful artistic proxy for the latter. Defamiliarising the one familiarises the other, and provides a way in to critique its unseen operation through visible means.

Art makes invisible order tractable by making it visible. Glitch aesthetics are all-over irruptions of the hidden technological order that reveal its operation through its failure. They assert not a reactionary nostalgia but a potential challenge to closure. Engaging with Glitch aesthetics allows us to exercise and develop our regard in a way that increases our fit to the smooth operation and to the catastrophes and contradictions of our post-digital environment.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Don’t forget the Glitch Moment/ums exhibition at Furtherfield

Curated by Rosa Menkman & Furtherfield.

Opening Event: Saturday 8 June 2013, 2-5pm

with Glitch Performance by Antonio Roberts at 3pm

http://www.furtherfield.org/programmes/exhibition/glitch-momentums