Marc Garrett: You are an artist who works solo and with others in various ways. A large body of your work consists of performances, interventions and sound recordings. I want to begin this interview by asking, why you decided to form ‘The NeoFuturist Collective‘, and what was the main mission or purpose behind such a collective?

Joseph Young: The NeoFuturist Collective was born as a convenient way to house a piece of work I was making called ReAwakening of a City. The idea had started as part of a practice-based PhD at SMARTlab UEL, but as soon I got funding for the project from the Arts Council, I realised I didn’t want to spend the next four years writing about it…

I invited a group of artists to join me in making a collaborative piece of work from a seemingly simple premise – the transformation of urban noise, inspired by futurist artist Luigi Russolo’s Art of Noises manifesto. Russolo had created a series of “noise networks” or symphonies for his mechanical intonarumori (noise makers) back in 1914, and in so doing he had influenced the entire course of 20th century music.

Despite his contemporary resonance, little is generally known about Russolo’s work, as all of his instruments were destroyed in the intervening two world wars. Of the scores he wrote, only the first 7 bars remain of Awakening of a City, and that only because it was reprinted in the art magazine Lacerba. Apart from the fragment of written score there are letters, reviews, photographs and other forms of documentation which have led researchers and artists over the years to try and recreate his noise making instruments.

Our project is rather different – we use the remaining 7 bars as the starting point for a new piece of work, ReAwakening of a City, engaging with all forms of visual and aural urban noise that we spend so much time trying to block out. Traffic noise, junk emails, health and safety warnings, advertising and street furniture. The form is performative, visual and mediated as well as musical, using all available means at the disposal of the 21st century artist.

By engaging with my artist-collaborators’ practices, I commission work that responds to this central idea and then set up an appropriate curatorial context for extending that individual response into a collective noise network.

MG: Where did these ReAwakening of a City events happen, and what kind of response did you receive when these performance, interventions took place? How important was it to connect with others – every day people, whilst engaging in the process of expressing these real-life experiments?

JY: The first ReAwakening took place in Brighton in Feb 2008. We started off the project by declaiming the NeoFuturist manifesto (written by Rowena Easton) in Jubilee Square, with a bunch of workmen and their drills providing a fabulously appropriate accompaniment to the text which celebrates Urban NOISE. (The manifesto can be downloaded from www.neofuturist.org). The crowd then followed us onto the Arts Council offices where we laid a wreath on their steps in support of all the companies that had been recently cut – we were ourselves in receipt of Arts Council funding at the time. A classic case of biting the hand that feeds you. Our activities provoked mild amusement and little controversy however, as the good citizens of Brighton & Hove are used to seeing “crazy” artists peddle their wares in public.

A couple of months later we had our first performances of work-in-progress at The Basement, Brighton. The reaction here was far more hostile and interesting, with some audience members questioning our politics in the Q&A session afterwards, accusing us of proto- fascism. Actually the level of debate was thrilling, as we really touched people’s buttons and ended in a deep discussion about the impact of the Futurists and their relevance to the current political climate. This question surfaced again a few of months later in an online interview with The Thing Is… magazine.

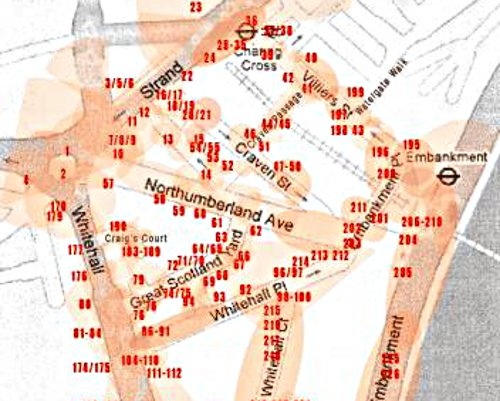

We were fortunate after that to be invited to make a piece of work on Wall Street in New York for the psychogeographic festival, Conflux. Our proposal was to make a walking performance that explored the everyday experience of living and working in the Wall Street district and how this might inform our understanding of the impact that this small area of real estate has on the rest of the planet. We arrived on September 11th 2008 to be met by 9/11 conspiracy theorists on street corners, and proceeded to spend several days mapping the area through sound recordings, text and video in preparation for a dawn performance on 14th September – a ReAwakening as the city awakes. The effect was dramatic and unexpected, as my declaration of the NeoFuturist manifesto outside 1 Wall Street brought about the collapse of Lehmann Brothers that weekend and the subsequent domino effect on the global economic system. Sorry world!

Our next major intervention was more low key, but no less dramatic as we were commissioned by Fuse Medway festival to engage with and inspire the village community of Upnor. Our mission was to get the people to take to the streets in a protest/celebration march. We worked with the community over a number of months, holding public workshops and meetings, networking furiously in the local pub (one of four!) and it soon became clear that the general apathy towards the arts, and outsiders in general, meant that if the public were not going to come to us, then we would have to go to them. So we took to the streets and made work in public which enraged some, who questioned where our funding had come from, but delighted others and built a momentum towards our final performance.

A Call to Arms (as the piece was finally called) took place in June last year and was a very successful example, I think, of how one can make “community art” challenging as well as accessible. See http://neofuturist.blogspot.com for full documentation and a film of the performance.

Other pieces of work, include shouting at the Futurist paintings with a megaphone, as part of the Tate Modern Futurist retrospective last summer. An experience as liberating as it was faithful to the original spirit of futurism, causing equal anger and delight amongst an unsuspecting public. I was also invited as a panellist to take part in a public debate along with other luminaries from the art world, on the subject of “Is the Avant Garde Passe?” organised by The Institute of Ideas in London. Here the public paid to witness a lively and informed panel discussion around the relevance of contemporary art, proving, it seems to me, that there is a real appetite for intelligent, politically driven commentary and debate.

A group of artists drawn from the fields of visual, performance, video and sound art will attempt to transform the everyday language of urban sounds and visual junk (such as spam emails and billboard advertising) into a true multi-media experience to do just that; asking us to question our assumptions about what is beautiful in a modern world of information overload.

MG: Your comments that contemporary art is in need of intelligent, politically driven commentary and debate rings true. In respect of my own art context(s). Thinking of the many amazing self-organised, networked communities, of which there are many, on-line and in physical space; there has been a massive shift of art creating, moving independently, yet in parallel to the ‘official’ and hegemonic examples accepted or considered contemporary at the moment. Of course, if we think about what contemporary means itself, it means existing, occurring, or living at the same time. The relationship between institutions and art which is actively critical and more challenging than easier processed art such as Brit Art, how they represent contemporary art.

Considering the history and knowledge we have regarding the original Futurist movement, and its close connections with fascism. For instance, what is less known is that, the Futurist movement did not only consist of fascists, but within it there were also socialists, anarchists, leftist and anti-Fascist supporters. Consisting of interesting individuals such as Georges Sorel, who explored his own views and intellectual thinking, right across the political spectrum. Georges Sorel “…was a voluntarist Marxism: he rejected those Marxists who believed in inevitable and evolutionary change, emphasising instead the importance of will and preferring direct action. These approaches included general strikes, boycotts, and constant disruption of capitalism with the goal being to achieve worker control over the means of production.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Sorel

I can see a direct link from Sorel’s activist approach and The NeoFuturist Collective’s ReAwakening events and performances. Of course, there are some other pretty good contemporary art activists out there at the moment, who also incorporate performance as part of their creative process; such as ‘The Office of Community Sousveillance’. “This work rests between legality and illegality. By posing as security officers, ‘PCSO Watch’ imaginatively play at the borders of what is typically deemed right and wrong, real and unreal, pushing their expression in the form of political enactments and direct action. This is a paradigm shift, not particularly interested in the art critic’s perspective.” http://www.furtherfield.org/displayreview.php?review_id=338

“Futurism has produced several reactions, including the literary genre of cyberpunk — in which technology was often treated with a critical eye — whilst artists who came to prominence during the first flush of the Internet, such as Stelarc and Mariko Mori, produce work which comments on futurist ideals.” The legacy of Futurism. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futurism#The_legacy_of_Futurism

With the understanding that there have been various influences, mutations and re-appropriations from the Fururist movement, I am wondering what elements you feel or think are still important to reclaim, reshape and reintroduce into a contemporary world, both in respect of the art arena and in relation to our everyday environments?

JY: What interests me in relation to the Milan Futurists is, first of all, the misperception, as you have pointed out, that futurism was primarily a fascist movement. My understanding is that Marinetti was the only artist to have that association, having been invited to serve on the Central Fascist Party Council after the First World War. He resigned not long after as soon as the Catholic Church was also invited to sit on the Council – Marinetti being an avowed atheist. This is not to excuse the entire movement of this problematic association, but it does put it in context. It also recognises that a spirit of optimism and a belief in technological solutions to the world’s problems, that futurism embodied, also has its’ darker side. And it is with this knowledge that I choose to engage with (neo)futurist ideas in the 21st century, as it seems to me, that in a world seemingly on the verge of collapse, that a spirit of positivity renewal is both urgent and necessary, and also the ultimate political gesture.

You mention various artist collectives that have appropriated the futurist legacy in this way, and to that I would add Ultra-Red who, incidentally, published a short sound piece of mine, recorded on Wall Street during the crash of 2008, as part of Fifteen Sounds of the War on the Poor vol.3.

In order to engage with the state of the planet, artists can no longer cling to romantic, utopian notions of nature/beauty in opposition to man/technology. This dichotomy seems to represent more about human self-loathing than it does about a workable solution to global warming/terrorism/the energy crisis/reform of global capitalism, etc. Moreover it leads us towards a new “medievalism” (ban air travel, ban cars, buy local) that is all too prevalent in ecological pressure groups. In this argument, man has brought us to the edge of destruction, therefore we must drastically scale back all of our wealth-producing activities. As if the (post)modern world could be wished away in either Luddite vision of the future or more worryingly in the ideology of The Zeitgeist Movement, whose apocalyptic vision of a radical eco-future involves tearing down our cities and rebuilding them.

This thinking is also represented in the work of acoustic ecologist and renowned nature recordist, Bernie Krause in his article, Anatomy of the Soundscape: New Perspectives, Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, Jan/Feb 2008 Vol. 56 Number 1/2, Pg 73-80 (2008), in which he dissects the soundscape (a term first coined by R Murray Schafer in Soundscape: The Tuning of the World) into 3 separate strata:

“GEOPHONY is framed as natural sounds emanating from non-biological sources in a given habitat.acoustic variations. BIOPHONY By far the most complex and laden with information, this unique feature of the soundscape is comprised of all of the biological sources of sound from microscopic to megafauna that transpire over time within a particular territory. ANTHROPHONY, defined as all of the human-generated sounds that occur in a given environment: physiological (talking, grunting, body sounds), electromechanical, controlled sound (music, theatre, etc.), and inci- dental (walking, clothes rustling, etc.).”

In this breathtaking philosophical leap, Krause removes the human from the natural environment and pits him/her in opposition to it. In creating a separate category for human sound activities outside of the biophony (i.e. the sounds of all other species on the planet), he is both over-stating human control and dominance over the environment and also denying us a role in the Gaia hypothesis – one of the green movement’s central texts, that views the Earth (and all of its inhabitants) as a single organism.

I am certainly not refuting or seeking to contradict many of the arguments regarding human sound activities and stress levels, posited by the World Soundscape Project, of which Krause is a prominent member, but it is worrying that so many eco-activists see humanity as a problem and not as a solution. And this is where Futurism and its antecedents/mutations can offer a way forward…

If, as I believe, we can find beauty within the drone (our drone), then the clamour of urban noise, both visual and aural, can be transformed in our perceptions into something of interest and value, rather a thing to be blocked out or ignored. If we can stand in a busy place such as Oxford Circus in the centre of London and open our ears to the sonic detail that is contained within the omnipresent drone of human activity, then we can begin to understand that activity as a creative as well as a destructive force. We can then harness and use this energy to power and revitalise the human spirit.

So, for me, the Art of Noises manifesto is the central and critical text in beginning to shape a new understanding of the contemporary sound and land-scape. If we can find a way of reframing urban noise as a meditative experience, as I recently did in my residency with Blast Theory, then we are part of the way to ReAwakening our cities as places of hope and optimism. To do this, I made a number of immersive binaural recordings of the area around 20 Wellington Road, where Blast Theory are based on the industrial outskirts of Brighton, and mediated these as iPod listening experiences in a temporary installation space that I set up for the event. When I came to retrieve participants from the room (they went in 4 at a time) they had invariably made themselves comfortable and been totally immersed in the sounds of the local traffic. They often described their experiences as “relaxing” and “enjoyable”, and how many times can you say that of the experience of standing beside a busy, urban, traffic-filled road?

So that is my mission for ReAwakening of a City; to take Russolo’s lead from the surviving 7 bars of his score to Awakening of a City (1914) and reframe and rework the paradigm of the celebration of urban noise to (re)awaken of all of the senses through a heightened perceptual shift in one of them – that of hearing; the neglected sensory cousin in our predominately visual culture. My ultimate ambition being to create a large-scale performance event for the 100th anniversary celebrations in 2014, in collaboration with like-minded artists from around the globe.

Featured image: F.A.T. Lab (Free Art and Technology Lab) were found causing trouble at the Transmediale.10 this year.

An interesting outsider project at Transmediale.10 this year, was F.A.T. Lab (Free Art and Technology Lab). A collective of artists, engineers, scientists, lawyers, musicians and trouble-makers who have been working together for two years, on the intersections of Pop culture and Open source. Their stapline describes them as “An organization who is dedicated to enriching the public domain through the research and development of creative technologies and media”. Beware, they love using the word ‘Fuck’. A lot! Which means they are cool, and some you grown ups may feel slightly unnerved by their over generous outpouring of flippant explitives, but the kids out there just love it!

You can read an explanation of their work in the about section on their website, and view a video presenting some of their ideas and works. With a simple rap base with nasty yellow and pink colors, it could be considered as a joke. Perhaps, to some degree it is, but at another level they are playing around with social contexts of the Internet culture’s, presumptions and acceptance of things. Through an omnipresent ludic approach they reuse what is given to us all with a contemporary pop attitude – showing us the many contradictions from these given systems. Proposing other possibilities in order to loosen and to free things up from the copyright laws and prescribed rules of both big companies and clumsy governments.

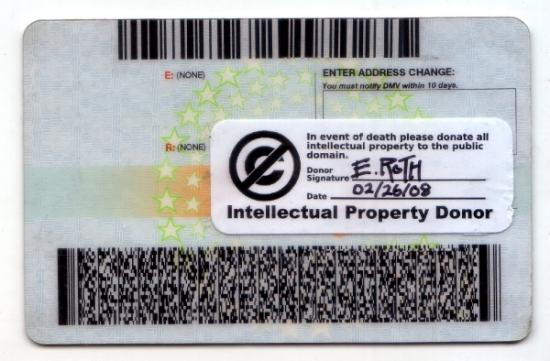

One of their projects called Public Domain Donor, consists of D.I.Y stickers saying “In the event of death please donate all intellectual property to the public domain”. They write “Why let all of your ideas die with you? Current Copyright law prevents anyone from building upon your creativity for 70 years after your death. Live on in collaboration with others. Make an intellectual property donation. By donating your IP into the public domain you will “promote the progress of science and useful arts” (U.S. Constitution). Ensure that your creativity will live on after you are gone, make a donation today.”Simple and humurous.

Yet, behind their process of cultural detournment exists a reference to earlier net art critique, by Critical Art Ensemble who way back in 1995 said “Each one of us has files that rest at the state’s fingertips. Education files, medical files, employment files, financial files, communication files, travel files, and for some, criminal files. Each strand in the trajectory of each person’s life is recorded and maintained. The total collection of records on an individual is his or her data body -a state-and-corporate-controlled doppelganger. What is most unfortunate about this development is that the data body not only claims to have ontological privilege, but actually has it. What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself. The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world. What we are witnessing at this point in time is the triumph of representation over being. The electronic file has conquered self-aware consciousness.” The Mythology of Terrorism on the Net. Critical Art Ensemble Summer, 95

Also as stimulating, is the idea Graffiti Markup Language, an XML file type specifically designed for archiving graffiti tags, and easily reproducing them.

For Transmediale.10 they presented a project called Fuck google, one of their more involved works, appropriating the image of Haus der Kultur der Welt, the futuristic bulding hosting Transmediale, formerly known as the Kongresshalle conference hall, a gift from the United States, designed in 1957 by the American architect Hugh Stubbins Jr. as a part of the Interbau exhibition. John F. Kennedy spoke there during his June 1963 visit to West Berlin. Fuckgoogle focuses on reminding us all how this big company has become omnipresent in our digital lives, refering to the risk that too much data is owned and is going to be owned more and more, just by Google alone. It exists as a collection of browser add-ons, open source software, theoretical musings and direct actions.

Not necessarily trying to be a definitive solution against the big G in any sense of the word, but more a reminder, a provocative virus to diffuse. So we have a graffiti firefox skin, fuck google pins, The F.A.T Pad or some plugins to reclaim your public individual space on your browser. Everything is D.I.Y and opensource, so you can easily replicate it. The approach can be find with FuckFlickr a free image gallery script offering everyone who visits a Flicker-like image gallery.

The F.A.T. Lab is an example of technological sabotage. Of course, it’s not a new thing in respect of the hacker community: using the instrument, medium directly, in order to change perceived assumptions of our reality. What is quite new is F.A.T. Lab’s blatant exploitation of everyday Pop culture and its language. The hacker counterculture has always had it’s own way of communication, built in the late 80’s and 90’s. These days, more and more people use the computer, not just hackers. Using Pop culture in order to communicate one’s message could be one possible way to escape the duality culture/counterculture. On the other hand, F.A.T. Lab could be creating a fresh paradigm which allows others who would not normally appreciate hacker culture or even media art culture, filling a space beyond art culture which could be considered as too refined.

Marcello & Gaia: Can you describe who you are and how do you connect each other?

Evan Roth from F.A.T. Lab: We are a group of friends. There’s not any formal application process or open call, many come from typical art organizations. It started out as a group of friends and then slowly, more friends joined. We also made more friends, collaborators on line. Here at Transmediale.10, it’s actually our first chance to meet face to face and some of us have not met before. There are two things that mainly characterize us. On one side, there is the open source culture and advertisement free culture, but also the idea that this all should be fun. Art and political activism doesn’t have to be a boring, the interface of it all, can be accessible to more people. We try to push this candy coding, get the those audiences who are using youtube videos, that is our primary audience. We like it when art organizations pay attention to us but really our main audience is at the borders of things, using different networks, commercial networks out there, happening outside of the gallery.

M&G: If we look at the projects you are showing here there is a kind of aesthetic in common, the colours are really interesting, the pink and the yellow remind us early 90’s spam. Is that aesthetic a primary decision, is the style you choose to define you, or has it just happened in the progress of your work.

E: I answer that in two. There is a thing from open source development culture that is ‘release early and release often’, we try to apply this model to the media production. We try to release ‘early and often’. If you are on the fence where you should release something or not and it is not quite ready, just push out the door, because it is better to have it in the public counter system than not. So the aesthetic of the website is in part probably pushing out the door rather taking care of the nuances or the color it is. We just try to get this thing published quickly. Someone could be sitting on their brilliant idea and waiting for years to release, waiting for some details and then you find that no one really cares about this in the end. But there is also an aesthetic interest in common, that comes from this ‘dirty style’. There is an artist friend, Cory Arcangel who is one of my favorites, and he describes the dirty style as ‘either you take little interest in design so it becomes so un-aesthetic or you over-work it to a point that the work itself becomes something too trivial’. We don’t have meetings about how the website is going or what it looks like.

M&G: Don’t you think that this “dirty style” is somehow hiding the real content or the message? The use of ‘dirty style’ is obviously an answer of the hyper sensibilization, concern of the form but at the same time this makes your work splitting in between the no-attention of form and pushes content in the corner.

E: The way our websites look matter’s less and less now, because people don’t go to websites for content anymore. Most of the traffic in the websites do not even see the pink and the yellow, design. There is some kind of form/function relationship going on. We are interested in rolling up this web 2.0 idea a little bit, and that’s what this installation here is about at Transmediale. The early 90’s aesthetic was with people hand coding html and making tables, not downloading a WordPress thing. In that sense, there is a sort of connection to the DIY, rolling back to the way of 1.0 – where the files are hosted in your own server and not google or yahoo.

M&G: Isn’t it more interesting to try and critique in a more constructive way, creating something else, not just another google appropriation but other kind of net platform for a community? Could that be one of the important challenges for artists now?

E: Open source is a big movement and free culture is even bigger and so we know that there are people out there hacking in this way right now, but we are not programmers, there are programmers taking part but these are not our skills. Our place in this movement is in the media side. We do have programmers in our group but we feel more like media makers. We make these videos and they are kind of funny and taking something from the pop/culture, twisting them, possibly people have a look and pass them around. But there are messages in them. And the messages are trying to reveal the money and the branding business that google is making and saying it is not cool, and being involved in an alternative open source culture looks better. We also have a development tool like fuck flicker and flv player where you can have your own videos up like you tube.

M&G: Why are you are supposed to win this year’s Transmediale? You stood up on the stage during the award claiming the award for yourselves!

E: Oh no, we don’t think we are supposed to win. Do you know Kanye West? This is a USA story, we joked about Kanye a little bit. We’re always trying to pay attention to what is going on in pop culture and surf a little bit. Kanye was notorious for interrupting a ceremony whenever he lost, grabbing the mic. As we were for this fuck google project – last night, the winner was a youtube related project, and google is a sponsor. The message we tried to get across last night, was a reference to this, and we are gonna have an official press release on it soon. But I think that for Transmediale, our project was an anomolie, showing this fuckgoogle in contrast to accepting web 2.0, which is actually a range of projects. We were surprised to be invited, who know’s what for? But we think that it was a very wise decision, and we are really happy to be here.

On their website you can get a clear impression of their feelings towards Google “So, what is so “fuck-worthy†about Mother-google? It is the fact that a corporate entity, even one as beloved and competent as Google, is in control of such a large stake in the digital network and public utility upon which we have all grown so reliant. And, that as a publicly traded company, it doesn’t have to answer to anyone but its largest shareholders, despite the fact that its decisions effect the lives and private information of millions of people. Few even question or raise a voice in opposition to the Google-ification of the Internet.”

There were more than 1,500 submissions for the Transmediale.10 awards, nine art projects were nominated and F.A.T. Lab was a runner up amongst them. Showing contemporary, activist art within a larger more incorporated festival is to be commended, it is not an easy thing to do. And we all know how easy it is to criticize rather than make something ‘real’ and positive happen. F.A.T. Lab are a tangible byproduct of a culture, caught in the trappiings of Hyperreal situations, a confused world losing itself even further into a perpetual state of denial. Pop culture and celebrity related banalities are constantly distracting our gaze. It is an interface which can only handle life via mediated proxy. F.A.T. Lab know’s this, and have adapted themselves to literally scrap with it on their own terms. Their role and place in the world is to get out there on the front line and go places where the common people reside. They want to be on the main stage battling it out, whilst challenging the interface presented to us all – making it their playground.

You can also read Marcello Lussana and Gaia Novati’s article about this year’s Transmediale.10 here…

Featured image: An interview with Chris Dooks, a ‘Polymath’ exploring various creative avenues, making his art using different media.

One of the many interesting and rewarding elements of being deeply involved in what, I’ll loosely term as ‘media arts’ practice, is the breadth of imaginative people you meet along the way. We first met Chris Dooks in 2005-6, when he worked with us on a project by Furtherfield called 5+5=5. We commissioned 5 short movies about 5 UK-based networked art projects exploring critical approaches to social engagement. These pieces offered alternative interfaces to the artworks and the every-day artistic practices of their producers. Including the motivations and social contexts of artists and artists’ groups working with DIY approaches to digital technology and its culture, where medium and distribution channels merge. Chris produced a film-work for the project called Polyfaith. A Psycho-Geographical Web Project introducing the beliefs and philosophies of his (invented) friend Erica Tetralix.

“My friend Erica Tetralix died. She gave me the task of fulfilling her dream which was that people would enjoy the parts of Edinburgh that were so dear to her in her life. She also loved tourists and sympathised with people on a budget, so she devised, with my posthumous help, this free way to enjoy the city. It’s a beautiful gift for both transients and residents. It’s popular with backpackers, parents and children, cultural groups and well, basically anyone.”

Later on we discovered that the name Erica Tetralix, is actually a name of a plant. Often called a cross-leaved heath, a species of heather found in Atlantic areas of Europe, from southern Portugal to central Norway, as well as a number of boggy regions further from the coast in Central Europe.

To view Polyfaith visit link below:

http://furtherfield.org/5+5=5/polyfaith.mov

The value of an interview is that it can serve as a useful documentation, a process allowing a kind of unfolding of time, All layed out in front of you. The reader can experience not necessarily a retrospective, but a dynamic and creative life and a personal history openly shared, on their own terms.

This interview reveals various levels and approaches by Chris Dooks. An inquistive and playful mind is at work here, engaged in exploring across different forms of personal agency, as well as redefining his practice in relation to the world he exists in, and the people he comes across in connection to various projects. His art is not a singular activity. Meaning, he does not rest in one particular art genre or movement. Instead, we are asked to acknowledge a personal enquiry formed from different engagements and choice of mediums, which happen to meet his creative intentions and questions at the time. We are all relational beings and Chris Dooks is a clear example of how this can work in an artistic context.

The Interview:

Marc Garrett: Many out there will already know you as a professional film maker, directing arts-based TV documentaries such as The South Bank Show in your twenties. Since then, you have developed other skills involving design, composing and making music, audio visual installations, explorative psychogeographical projects, as well as continuing making films, and you’ve even got a record deal. You have as far as I can gather four different music projects curently on the go, your electronica group BovineLife, an architecture music project known as As Ruby’s Comet, Feible for laptronica and also the Audiostreet project featured at The Leith Festival.

Chris Dooks: It’s amazing how many people still know me from Bovine Life which was a moniker I used for an internet audio project way before broadband in 1999. It’s the tenth anniversary of my bip-hop album SOCIAL ELECTRICS and I would like to make all my albums available for free for furtherfield readers. Don’t let itunes rob me of any money! The transition to musician was down in part to the South Bank Show when working with Scanner. I was really frustrated at making work about musicians. And the technology was making it easier for folks like me without a classical training. Here are three for you for free – check links below for free tunes at the bottom of the interview.

South Bank Show UK television documentary directed by Chris Dooks, featuring Robin Rimbaud speaking about his practice and ideas. 1997. Click here to watch video.

MG: In The Glasgow Herald, in Scotland a journalist called you a Polymath. Even though you were delighted to receive such a compliment in the local press, you decided to re-edit the term, reclaim it so to make it less seemingly mathmatical. Prefering Polymash because it sounds “friendlier, resourceful and potentially charming.” Sticking with this notion of you being a Polymath or rather a Polymash. Your diverse approach in creating art works in a non-singular approach, is a core element of your practice. I was wondering whether this is a deliberate decision or a natural and overall state of being?

CD: It’s weird though, I learned more in my background as a wedding videographer aged 14-19 (35 weddings at weekends!!!) than on any other course. Doing weddings gives you various skills as a digital artist. Fuck a film degree! As a wedding videographer, you need to be able to mike the vows in difficult audio environments (i.e. reverby spaces), film it about fifty feet away, liaise with highly emotional temperaments, be like a war photographer – it’s only gonna happen once, miss it at your peril – and stay sober. Not to mention edit it at a time when non-linear editing was non-existent, (I remember the heady days of “crash editing” between two panasonic VHS machines) white balancing everything on manual heavy equipment and creating all the graphic design and labelling of tapes. I was like a teenage record label!

So in 2009 when I made www.studio1824.com – making a record (netlabel) for an icehouse in Sutherland (remote Scottish Highlands) I got a kind of deja vu experience. Only with an education and life experience in the mix now.

When I was 8 years old, I had two epiphanies. One was that death is really gonna happen, and two, that cinema is wonderful, emotional and that it offers us a naive form of immortality. Cinema was the only artform that even at that age, I felt could make me feel…spiritual, for want of a better term. I became quite religious.

I was obsessed with super 8 cameras and video. And now I am trying to get all my pre-teen works tracked down! But even at this stage there was always a healthy distraction in other areas. I wouldn’t get involved with narrative and this has never been my strong point, even though I was reasonably good with words. My uncle played a lot of classical music and my dad took me all over the UK in his lorry, and at this time I won a scholarship to play the cello at school with the posh kids, being the other three. (It was a working class music “initiative”) But alas, I didn’t realise how lucky this was for me. So I went back to making videos, this “poly” approach was probably set quite early. I remember doing a kind of pre-Blair Witch thing when I was 14 and I would get sidetracked into filming the shapes of the leaves and the sound of the wind. Then I realised that the material didn’t make sense in the conventional sense. So I became an aesthete of kinds at an early age. And in every way, from Granny’s trifles and an early lust for Kate Bush, I was concerned with the sensual world. But until 22 I was monogamous to film projects and would work as a corporate director in the art school holidays to fund my college life, with the odd wedding video thrown in. By the time I did my film degree at Edinburgh College of Art, I was much more interested in people like video artists Bill Viola, Gary Hill and Daniel Reeves – (I met all three) via the “team-building” world of film shoots. Bill Viola’s THE PASSING changed my life.

The Passing, 1991. In memory of Wynne Lee Viola. Videotape, black-and-white, mono sound; 54 minutes.

Pre-degree, in those days (1989-91) you had to REALLY know your kit and be a good all rounder. I trained on huge Umatic machines and did a BTEC before a degree. I was from a part of a culture where there was no film degree, and I was a couple of years behind my peers. But by the time I hit ECA, I could mix radio programmes, edit timecode, black and white balance studio cameras and location kit and I spent most of the time buggering off to the hills to film Scottish waterfalls. I might have been techinically proficient and this was behind the poly approach to an extent, but I had bugger all conceptual skills. These have only really solidified in my thirties…

MG: Lets talk about the Surreal Steyning psychogeographic audio tour, part of the The Steyning Festival in 2009. On the web page for the project is written “This tour is simply a different way to skin the proverbial cat. In this case, the cat is Steyning. In fact, if you think of Steyning as a cat, you are already a psychogeographer. Well done. You’ve engaged your psyche with geography. You’ve mapped the town conceptually. The High Street becomes the cat’s spine with the head chasing Mouse Lane. Now you are in the same company as such artist groups as the Situationists, the Dadaist Movement and other high fallutin ripples in art tourism, and even The Ramblers.” Did those who took part manage to understand and appreciate where you were coming from? Also, how did it work?

CD: There was a tiny degree of spin with the site’s headline Traditional English Town Embraces Conceptual Art Walk but by and large folk did embrace it and it would have been patronising not to drop a little sand in the vaseline, not to deliberately challenge, because the Steyning Festival, was, I felt, in danger of being a little like a tasteful village fete. A good fete I might point out, so this year, there was something brave about them putting a conceptual artist at the heart of a residency in the village. English villages like Steyning were not and are not, all tasteful. Whenever I encounter these tasteful expectations in the arts, I think of that Stereolab song, Motoroller Scalatron with it’s chorus “What’s society built on? It’s built on blood. (some say the lyric is “bluff” not blood but either way it works)” So I saw my role not as a socialist historian, because I wouldn’t have a clue, but as someone who encourages an enquiry per se into unusual histories, paganism, aesthetics and philosophies of very local travel. I mean, I don’t think there’s anything angry or unloving in the tours. In fact, I try to make them about folk being nicer to each other. These activities have a small socialist agenda but as a performer, I am not exactly Stelarc, slashing my wrists in the street. I’m not about shock! However, this tour had a couple of “jaw droppers” (See The Steyning Star on the tour). The main outrages came from people who wanted a straight history tour and were not given one, depsite my first words on the tour saying “this is NOT a history tour!”

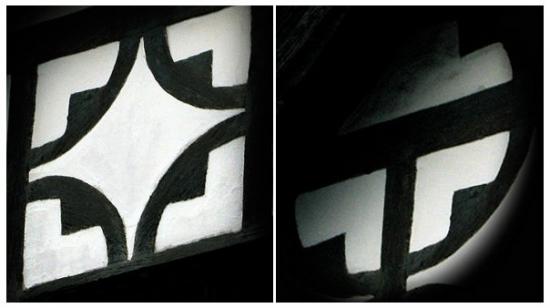

Example taken from section 4 of the The Steyning Star on the tour:

“This is Brotherhood Hall, built in the fifteenth century and now part of Steyning Grammar School. Look closely at the symbols which adorn the gables. They may look like simple decoration to us, but these markings are rather unusual. They have been the subject of no fewer than three PhDs, and for a century the world’s leading symbologists have engaged in hot debate over how to read the meaning of them. One of the most important questions is what shape we are dealing with. While some people see predominantly circles, others see squares and diamonds, rather like those tiles that everyone had in their bathrooms in the 1970s.”

“Was this a pop premonition? For some time it seemed so, and this remains a strong theory. But in the mid 90s the school took part in a German exchange programme, and visiting German students proposed yet another alternative. When they looked at the patterns on the gables they saw a cross drawn within the circles, or a gammadia, to be more precise. A gammadia is a cross voided through, or a cross formed with four of the Greek letter Gamma. It looks a bit like an ‘L’ to us. The swastika is the most famous example of a gammadion. The German students believed that this was not a pop premonition at all, but a foretelling of the success of German heavy metal band Gamma Ray. This theory also gained popularity among members of the school’s very active astronomy club.”

The festival had hired a PR person to market aspects of the festival and commission an artist, and so I was brought there with a little Arts Council of England fund, so felt obliged to make work with the tools I’ve been developing – or my “brand.”

Nothing was watered down simply because it was a village (it’s actually a town but it feels like a village) because it would have meant compromising the ideals or enquiry, of looking deeply and into the areas of my interests of paradolia (faces in chaos) and simulacra formations (things that appear to be other things).

Most of them got it! I mean, it was nearly two hours long and they stayed till the end, although it did split the audience, but not badly. 2-3 out of 20, left. We had to do it again the next day due to popular demand! The ones who stayed had smiles on their faces by and large, which made me very happy. The weird thing was, not once had it been stated that it was a “straight history tour”, and it should have been obvious within the first thirty seconds that I make some of the stories and hypotheses so outrageous that surely this is tongue in cheek? However, I had written some slightly anti daily mail sentiment in it and two or three people angrily walked out of the tour. I got that wrong. It’s a Tory (conservative) heartland, and I don’t think you can be an artist and right-wing, you are just too aware of the world, but I should have considered this aspect more.. My landlady was one of the people present in the audience and she walked out, that upset me a wee bit.

But there’s something about my personality that makes people trust me in my tours, folk are quite sweet and gentle perhaps. The message behind the tours is one of re-imagining everything you hold to be true. The motivation behind these tours is to see travel as something that can be done anywhere. People go to the other side of the world to enrich their lives, many don’t even journey over to the other side of the street, or drive through a different part of town! I find that hilarious. So for me, psychogeography is about the chicken crossing the road..

If we can’t even do that, what hope is there for atheists like me (who find Buddhist philosophy and its practice the only religion without the conceit of the other big hitters) who are forced to approach the world from multiple angles, because we can’t accept the idea of monotheism and monotheistic thinking. This single mindedness of approach, when challenged (not just in religious people, but people stuck in their ways) is bound to create a bit of friction even on a playful level like in Steyning.

I became invloved in Surreal Steyning based on another project, in Brighton, where I made several songs about a building on Brighton sea front. This was a song cycle, based on a very specific bit of geography.

There is this idea that psychogeography is only urban – but I prefer to bring this intense work to the home counties! After all, the whole point of being an artist is to see through the privets, the darkness of the forests. So while I was in Steyning I was reading about Alistair Crowley and witchcraft and when Steyning used to be a port – it’s now land, ten miles inland! In the middle ages everything was different. I think a lot about how many contemporary English folk in these wee villages don’t realise their own foundations. I found Steyning a really charged place and not just a twee place to get (admittedly excellent) cream teas and real ale (a bit flat for my northern British palette).

This was, without a doubt though, the most successful public psychogeography tour I had done, even more than Polyfaith. There have only really been three tours – Polyfaith, Select Avocados and Surreal Steyning. And Surreal Steyning learned from the other two – so I had my schtick by then. I think it’s the best executed one so far. Let me be clear, I care about the audience. I adapted to their demographic, their language and their refinery in this tour, but I really care about people, but what I hate is bigotry and there was a little bit of friction about some of the left-wing ideas in the work and some of my own goals. But they needen’t be upset by a Middle East reading of a thatched cottage, the similarities of Tudor graphics and the 1990s version of the Take That logo, and the roof of some flats that might look like an arrow.

MG: This critical approach of consciously making room within yourself to understand or at least appreciate the sensibilities of others, surely it must be a difficult task to accomplish? What I find fascinating about your engagement with the public is the measure of respect for them, mixed with a healthy level of detournement.

Thanks! I actually think it’s a big complement to have the public stay on a tour for up to two hours, or buy one of my records. So I’ve really tried to attack attention-deficit tendencies whenever possible. It’s also my grammar. I don’t really do critical theory, although to apply for money you need to know where your bit of culture fits in with others. I really dig a good bit of popular culture. I think the best stories in our culture in the UK can all be seen on Jimmy McGovan’s The Street. He is a master of audience respect. Also, I feel confused by a lot of art, so I like to call a spade a spade, unless I am in a surreal mood and I’ll call it a Sad Ape (Sad Ape is an anagram of A Spade).

I had a slightly uncomfortable childhood and adolescence That “public” thing comes from Teesside. I also particularly like North of England humour – and actually I really like it when “clever shits” (to quote my Granny RIP) get usurped by that kind of spit-and-sawdust philosophy. There’s something survival-like and super-clever about grass roots humour because it comes out of neccessity. So I think my own personality is a bit of art school but with angry chips on both shoulders. It’s why working in Scotland is great, because the Scots hate bullshitters – especially the Nathan Barley set. I always found that very attractive. I remember seeing and being heavily inspired by Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer’s first series and thinking, this is a dangerous combination! Northern swagger and charm! Dada! but with more academic kudos than might appear at first glance. And it was bloody funny! It was both alienating and accessible at the same time.

I grew up in Teesside and North Yorkshire and school never encouraged me really. I never had a bohemian upbringing, but I believed in the soul and went to Sunday School (my own choice – I was very religious for a kid). But I probably owe my interest in orchestral and “difficult” music to my uncle, and this was partly my first exposure to other worlds – I was particularly inspired by Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. And I liked that piece because it had something I could relate to (the church organ), it felt something otherworldly – both the sustained drones and mechanical math-like, transcendental nature about it. And no words. I remember talking to my music teacher about it. She got all excited and presumed I could play it so she got me the sheet music to learn it. But I could never do it, I had no discipline. Anyway, that piece was amazing, spiritual to me. When you thought it couldn’t end, it changed scale and key and ascended to even more articulate heights, clever and gorgeously aesthetic at the same time.

I failed art. I grew up around lorry drivers, grandma’s trifle and Christmas at working men’s clubs. A lot of nice memories but I’ve always been looking for ways to sweeten the sour ones. And then, a huge affliction came. Around twelve, I started to have these really strong life changing shocks, like my psyche being ripped to shreds – just by thinking, enquiring, looking deeper. I would call them “dark epiphanies” later. They are still with me. Adulthood has not softened them. I’m always on the lookout for liberation! Like Russel Crowe in A Beautiful Mind he learns to live with his Demons and accept they are there! I’ll never get over these mortal messengers, but it’s what underpins all the puns and humour in the work. Tears of a Clown maybe? At the time, (aged 12-15) there were pennies dropping about mortality – real hopelessness of mortality. I’m still dealing with it. The problem is, because these visceral thoughts will never go away, I have started trying to make them my teachers. And all I want to do across all of my works is reduce anxiety – mainly my own – and look at multiple universes – and I think we forget that your street is part of the universe. That’s where the work begins, in your block, your local Lidl – these places should teach you as much about our ridiculous situation as anywhere else. It’s like that idea that “the environment” is outside somewhere, when really it’s in the most mundane places. The mundane is “supramundane” at the same time. It’s no wonder I became a Buddhist in my early thirties. I need to get back into it. I’m getting somewhere maybe.

MG: Perhaps, it is not just about re-inventing a selection of different mythologies, histories in relation to localities, whilst exploiting contemporary mediums; which includes elements of satire, a certain level of hyper-reality.

CD: I think it’s about a hatred of authority, not because we don’t need order, I think we do, but authority takes all the colour out of our history and culture. I watch X-factor, like Peter Kay (underrated surrealist like most comedians – despite the professional Northerner get up). I never liked punk and thought anarchy was really stupid! Civil disobedience maybe. I hate it when I see musos on the telly talking about punk, getting all nostalgic. Maybe the Clash. Maybe it’s the patronage of culture by high fallutin’ types I don’t like. Because patronage kills proper culture doesn’t it? And because of that, I never got passionate about history at school. It was a bit grey. So what do I do without the arsenal of the passionate historian? I make bits up and flirt with it. These projects mean I have to know bits of history now. And this bit is really telling – the bizarre thing about the hyper-reality aspects of my tours and other works – is that the bits I make up and flirt with – those bits are often scarily close to the truth. Also you say I’m really respectful to the public, but I like to push it a lot. In Edinburgh, on the Polyfaith tour, folk were swallowing my wildest tales about the city when they’d lived there all their lives! I came in under the radar I suppose. I like usurping the pompous stuff with a passion though, I really do, I feel it’s my duty!

MG: There seems to be a kind of niggling question in this work. I get a sense that this question does not only relate to asking those who take part, but also yourself. It touches upon something quite raw, authentic and complicated, and untouchable at the same time. I am not referring to the sublime here, it relates to all of our collective histories, on this earth. A Genealogical form of re-assembling, re-knowing and perhaps not knowing. Are you trying to make contact, or reconnect some how to a type of authenticity; if so, what does this look like in respect of your intentions?

CD: I want to find spiritual relief. That’s a terrible word – maybe the sublime is better. Fuck it, I want it back from the New-Agers. Even though I am a total Dawkins fan, and am partly liberated by looking deeply, I just want a bit of peace really. And the tours train me to think outside the box, that’s it. I suppose it’s like doing my own philosophy degree “in the field.” But there’s a bigger box I am being prepared for (see what I did there!). There’s not much relief. I am a highly charged person – some would say high maintenence! I’ve just seen the Andromeda galaxy from the back garden. I want more of that. This is a really hard life. I want to be less fat. I’m sick of having M.E. My wife is pregnant. Christ, I am going to be a father. Maybe that will help my afterlife woes. Men aren’t supposed to moan. I’m being genuine here though. I forgot to mention Derren Brown. I’d love to do a project with him. I am sorry these answers are not very articulate. It’s in the tours! Do them!? Seriously, do the tours.

MG: What qualities and values do you think or feel this form, process and working offers yourself, the world, art and culture on the whole?

CD: I look at my place in the digital arts as a priest being sent to a remote parish – so hopefully we’ll clean up here in Ayr, our new home! ha ha! A lack of funding might make that difficult but it hasn’t stopped me before. My current thoughts are… Paradolia and Simulacratic Forms as narrative agents for psychogeographical tours. The benefits of the sustained drone in music. “Dayglow” hues and man made fibres in landscape photography. High hills. The idea, place and value of the troubador in the present age and the potential of “singing the news” as a deterrent for media-saturation. My next project may be about folk-music and psychogeography, using local folk clubs to make popular songs based on themes by bloggers. Some of the things I think of, I sometimes see being made around the time. A bit of Zeitgeist, collective unconsciousness awareness maybe! I am also still digging around popular atheism and the atheistic roots of Buddhism. Folk-Art and the search for genuine Scottish culture as opposed to the much-touted facsimile. These are my daily concerns. A project that I should mention is Ayrtime. A series of eclectic cultural events presented in the heart of Ayr, Scotland. Gigs, Theatre, Literature, Astronomy & more – on this site you can find archives of the events with beautifully crafted podcasts!

My work offers me the stuff I was told at school really. No different to building or plumbing on one level. Just a sense of achievement and pride I suppose. Quite traditional aims. I remember a conversation with my dad in the last few years (we row a lot) in The Ship Inn in Marske. I asked him why he never wants to know about all these fantastic projects I’d done! And he said “Well that’s your work isn’t it? If you were a plumber we wouldn’t be sat here discussing U-bends” and at first, I felt slighted, I’m not a plumber I’m an ARTIST goddammit!! It made me think of The Cohen’s Barton Fink, human and pretentious character “The life of the mind, there’s no roadmap for that territory” but on reflection it’s quite good to be making this mad work in working class areas, to take my artist ego down a peg or two. Lord knows I need it sometimes because I have two fights generally – the first is the fight to get work funded and made and promoted and so on and it be stimulating work. The second is the fight with M.E. which I feel like I am totally on my own with a lot of the time. I get really unpleasant symptoms, often with no break for weeks on end. Sometimes I can only do 30 minutes of work in a day. Sometimes, even that is a pipe dream. I’ve had twelve years of this shit. I was directing arts documentaries for telly when I was well. The upside of the M.E. is that it is humbling. I’d probably be that Nathan Barley wanker by now, and I wouldn’t have touched the Buddhism, the philosophy, proper art and gotten arts council funding without the lessons I have learned.

Social Electrics 10 year Anniversay edition 1999 – bip-hop.

You Know, You Love Something Little – Lost Vessel 2002.

The Aesthetic Animals Album 2008 – benbecula records.

www.eleanorthom.com

www.karencampbell.co.uk

www.alanbissett.com

http://www.louisewelsh.com

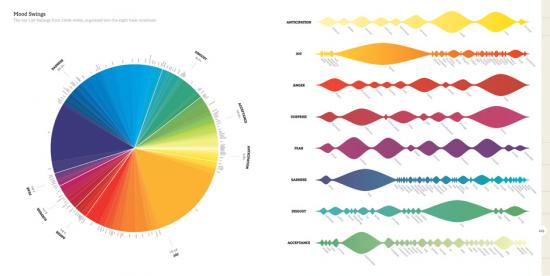

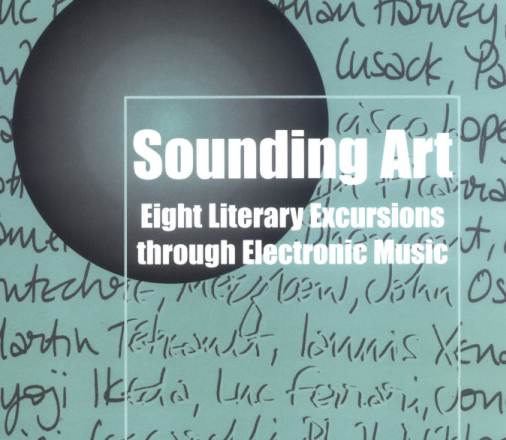

We Feel Fine: An Almanac of Human Emotion

Jonathan Harris and Sep Kamvar

Scribner Book Company, December 2009

ISBN 1439116830

Featured image: We Feel Fine project poster

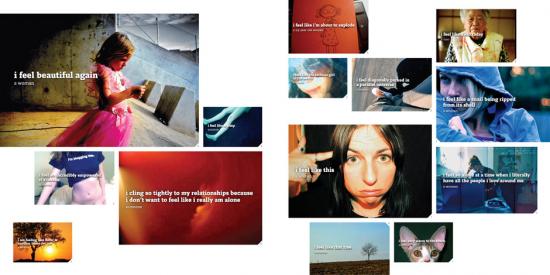

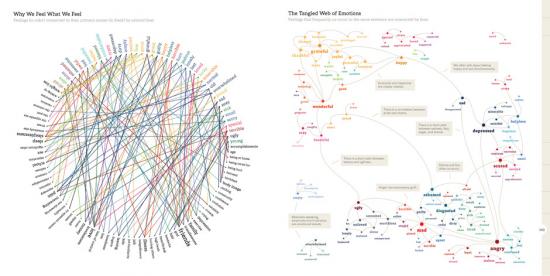

“We Feel Fine – An Almanac Of Human Emotion” is a hardback book that in just under 300 pages of well designed montages, data visualisations, diagrams, illustrations and text presents and analyses the data gathered by the We Feel Fine project. Started in 2005 and launched in early 2006 by Jonathan Harris and Sep Kamvar, We Feel Fine is based around a database assembled using a webcrawler that searches the blogosphere for statements of the form “I feel” or “I feel like”. Any matches are stored along with as much contextual data as the webcrawler can find (a photograph nearby in the blog post, the poster’s age, gender, and location, local weather). The database contained twelve million such entries by the time the book was published.

Sections of the book categorise statements of feelings by age, gender, the location of the poster, and subject of the statement. Individual statements are presented superimposed over images found in the same blog post. The photographs presented with their accompanying expressions of emotion have a high-contrast, shallow depth of field, and highly focused look that resembles Lomography. But this is a product of the presentation of photographs on the web rather than an hipsterly ironic invocation of the contingent aesthetics of mass photography. The images are for the most part JPEGs, and show the contrast, mach banding and visual noise of that technology.

The montages of “I feel…” statements in a standard format superimposed over an image found in the same blog post serve to provide a (sometimes incongruous) context for the statements that the project is based on. They resemble Gillian Wearing’s “Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say” 1992-3 featured photographs of people holding up placards on which the artist had asked them to write down what was on their mind. Going back further into the history of art, the montages and in a novel way particularly the data visualisations and graphs bear comparison to Vermeer’s seventeenth Century paintings of bourgeois social relations and reverie. Both “Girl reading a Letter at an Open Window” and “We Feel Fine” present social class, social self-presentation, advanced communication technology and consideration of the thoughts of others in a medium and way that epitomises the way people see things in that era.

The book’s volume of data and graphics quantifying social phenomena might resemble a “state of the blogosphere” corporate social media report in some ways, but its presentation directs attention back to the emotions featured rather than trying to tie them to any corporate or governmental agenda. This is a book by, about and for individuals in contemporary mediatised society. I found reading it became quite overwhelming sometimes once I had adjusted to its presentation.

Dictionary definitions, statistical breakdowns of the kinds of words, ages and genders of bloggers and other demographic and affective data are presented in compact graphic form on every page, and larger charts show more general conclusions. Feelings, or the words used to refer to them, are shown to vary between genders and as people age. This is an exemplary application of Edward Tufte’s science of the graphical presentation of information. They even have sparklines. But that science is applied to data that is at its heart qualitative rather than quantitative.

Such “data visualization” was a hot trend in 2009. Visualisations of crime rates, corruption, climate change and other issues can be produced using such data, and have become an important weapon in the arsenal of visual persuasion. On the We Feel Fine web site, feeling data is mapped to coloured blobs in an interactive user interface to the constantly updated (every minute) database. In the book, feelings and demographic information are processed to produce graphics that represent the prevalence of feelings over time, between genders, in different locations and in relation to each other. But as visual persuasion this is directed back to the vividness of human, qualitative experience rather than a more political or economic agenda.

“Sentiment analysis” was also hot trend in social media marketing in 2009 and its limitations quickly became apparent. Current systems simply cannot handle irony, sarcasm, regional differences in the usage of words and in many cases even simple negation. The We Feel Fine system is an exercise in gathering affective or sentiment data to visualise, but it avoids the pitfalls of sentiment analysis by automating only the gathering of the statements of emotion themselves, not analysis of how they relate to what they refer to. This is a classic example of well-chosen limits strengthening a project.

The problem of the relationship between qualitative (how you feel) and quantitative (how many people feel what you feel) data and how to deal with this in a non-voodoo way are avoided in We Feel Fine because of this.

Another 2009 hot trend was “big data”, the assembling of datasets that vary from many megabytes to many gigabytes in size. Datasets from regional and national governments, scientific research and freedom of information requests can be used in “data mining” to search for facts among the numbers. The We Feel Fine system is a good example of a big data dataset (and API, application programming interface, for accessing that data over the web). Unlike global temperature data it neither offers the possibility of objective accuracy nor involves any great risk if it lacks it. But it does reintroduce the human subjectivity that big data threatens to replace with numbers.

The striking thing about this is that although the We Feel Fine book is very much of the zeitgeist for 2009 the web-based system it presents started five years ago in 2005. At that time blogs were regarded by the mass media as disposable, narcissistic and somehow inauthentic. They were an unlikely subject at that time for art concerned with the authentic expression of emotion. We Feel Fine’s history, subject and results therefore both prefigure and go beyond the current state of the art in Internet social and corporate culture.

Harris and Kamvar are admirably candid in laying out the history, methodology, technology and in the case of the book’s production even the finances of their project. The code listings included in the book are tantalising glimpses into how the We Feel Fine server works, allowing a rare chance for students and artists to study such a system, and are licenced under the GPLv3. The book is under the obscure but principled Creative Commons “Founders Copyright” licence which will automatically expire the copyright on the book in twenty years time. This is all invaluable for critique and study of the project by artists, academics and anyone with an interest in art and technology, and more artists should do it.

In the FAQ and other essays contained in the book Harris and Kamvar are open about the methodological strengths and weaknesses of the We Feel Fine system. They acknowledge the limitations and demographics inherent in profiling bloggers (who are younger, wealthier and more technologically savvy than is usual). They also make a convincing case for the very real conceptual strengths of the project, discussing how the system holds up as science and statistics. And the project itself is overwhelming as an aesthetic and, strangely, somehow as a social experience.

Even if we don’t deny or question the existence or status of emotions for ideological reasons, do we know what we really feel? And even if we do know what we really feel can we really express it in a way that will be understood by others? We Feel Fine doesn’t address these questions. They are outside of its scope. Its acceptance of sentiment at face value and its mechanical (re-)production of representations of sentiment might look like the hallmarks of kitsch. But that would deny the subjectivity of the original authors of the expressions of sentiment that We Feel Fine processes. And a progressive art needs to represent the masses, not merely rulers and pop stars. Not everyone will be feeling ironic or critical on any given day. Given this, the transparency, scale and effectiveness of We Feel Fine mean that ideological objections to big data, to emotional taxonomies, or to the very idea of emotion face a problem in the project’s aesthetic and affective success rather than vice versa.

Some of the stories found while researching the posts and presented in the book are heartbreaking or uplifting, but the statistical nature of the project makes these outliers – they are rare events and can be identified as such. What comes through from page after page of casual statements of feeling is an impression of the range of human experience, or at least the range of human expression. If you can adjust to the montage format and the diagrams then the book can inspire sympathy, pity, and joy for your fellow human beings.

The book ends by considering the philosophical and spiritual meaning of feelings, how they affect our lives, and what we can do about this. The data gathered to back up this consideration makes the conclusions both persuasive (this is a paradigmatic representation of humanity) and surprising (that would be telling).

We Feel Fine faces up to the challenge of making Internet art that realistically deals with the scale of the contemporary web. It does this by tackling the millions of daily new entries in the blogosphere but crucially it retains a focus on qualitative, subjective human experience. In its engagement with multiple levels and kinds of representation, from emotional taxonomies and statistical methods to digital photography, weblogs, and data visualisation, it shows just how broad are the range of systems and modes of depiction that artists can and possibly must deal with today. And it’s a project that simply wouldn’t exist if the people who made it couldn’t code.

We Feel Fine is a persuasive and insightful portrait of the individuals that make up the blogosphere. It can be overwhelming in terms of the amount of information and in terms of the volume and strength of emotion presented, but that is part of what makes it vivid. It is a paradigmatic, realistic and persuasive depiction of the qualitative experience of individuals within networked information society.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Featured image: Photograph of a creative experiment on more intelligent modes of inhabiting the planet

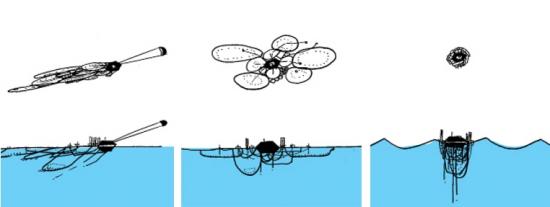

Open_Sailing‘s biggest achievement is perhaps to have turned our future into an open source project. Led by a group of enthusiasts, gathered around the idea of “we don’t know what will happen, but together we can invent our future and cope”, the project puts forward a very ambitious, action-driven, experiment-led, way of thinking forward. After meeting with the founder of the project, Cesar Harada, Open_Sailing proved to be a much more complex enterprise than I originally thought.

Initially the project started by mapping threats, the idea being that threats can produce something else than fear. Indeed Cesar Harada, was decided to turn threats into design constraints. This constitutes an interesting methodology to deal with the current climate of fear. The exploitation of threat has become the standard procedure to stabilize a permanent state of emergency. Mobilising virtual threats, states acquire exceptional powers that facilitate the implementation of ever more pervasive measures of control. The current case of swine flu is the last of a long list of exercises of mass modulation of fear. War on terror is the paradigmatic one. On the other hand, and following the warnings of the Maya calendar, all sorts of popular tales for an apocalyptic 2012 have started to populate the planet.

The role of Open_Sailing is to function as a catalyst that channels all this energy into the production of a better future. In short, its role is to transform fear into hope. Certainly this functioned as a strong attractor for new collaborators and soon the team started to grow. After putting together large amounts of real-time data about all sorts of dangers such as tsunami, terrorist attacks, nuclear accidents or pandemics, it became clear that the potential safest spots on earth were mostly located at sea. That led to the idea of designing the infrastructure necessary to inhabit those spots based on the concept of ‘Open Architecture’. Fear had been successfully turned into an active force unleashing the creative process. Inspired by this initial concept the Open_Sailing team started a very intense process of scientific, technological, architectural and artistic research that resulted in a first prototype awarded at Ars Electronica: Open_Sailing_01.

“A drifting village of solid and comfortable shelters surrounded by flexible ocean farming units: fluid, pre-broken, reconfigurable, sustainable, pluggable, organic and instinctive.” [1]

This drifting village, which is about 50 metres in diameter and can host four people, is designed to respond to its environment, being able to become compact and endure severe weather conditions, and spreading out to harvest in calm situations. Open_Sailing_01 was supposed to set sail last May 2009 but mis-coordination in the production with Ars Electronica delayed the plan. In the meantime, small intermediary prototypes of different modules are being built and tested constantly, but the Open_Sailing team hopes to put together the main modules of the International_Ocean_Station for general testing by the summer 2010.

One other important thing that came across in the interview with Cesar Harada was how soon after Open_Sailing was set in motion, it became clear that the project was not only about escaping the problematics of our society. It was definitely not an idealistic utopia happening elsewhere and starting a world from scratch. Rather than an exercise of escapism, they realised that the idea of inhabiting those sites where there is no threat had become an experimental laboratory where to grasp the future. Indeed Open_Sailing is very much about finding ways to face and deal with the very problems of our world.

“Be it overpopulation, global warming or energy conflicts, we are living in a time where ‘Apocalypse’ beckons. We need to collectively invent and spread bootstrapping DIY technologies for the forthcoming challenges, not only to survive but to re-invent how we inhabit this planet.” [2]

This became particularly obvious when the team flew to Morocco to try out some live-saving structures. Between the coast of Morocco and the Canary Islands in Spain hundreds of illegal immigrants die every year at sea. A high-seas permanent shelter would provide a low cost life-saving facility for the migrants.

This particular instance is also paradigmatic of the way in which experimentation is carried within the project. Future thinking is developed through material instantiations. This very characteristic process of design and engineering disciplines gives Open_Sailing an exciting palpability, a materiality, a commitment with actualisation that accounts for its potential to bring about real change. Commitment with results drives the project away from the artistic disciplines, but the poetics of the project undeniably brings them back together. A project that in a year of development has acquired such a level of complexity necessarily had to go through a very intense and accelerated process of conceptualisation and experimentation. And there comes the figure of the enthusiast, an experimental survivalist who is willing to take a plane the morning after an idea has come up to participate in a military training testing life-saving technologies.

Even more interesting is perhaps how this enthusiasm becomes contagious and the project starts to work as a truly open source venture. Open_Sailing becomes a powerful autonomous entity that keeps bringing people in a dividing itself into labs. Each new lab engages a whole new group of contributors, with a new set of preoccupations and hopes. The project proves to be definitely not about the implementation of a master plan or utopian blue print, but an example of how open source can literally be applied to the construction of alternative worlds. Within these labs we find different experimental research projects focusing for example on mesh networking; pollution, climate and natural reserve monitoring; sustainable aquaculture in high seas; or energy autonomous systems that generate electricity through wind, sun or wave power.

Now, there is of course the problem of co-option. The research being done is a very useful material with infinite commercial and even military applications. But perhaps this is not something that compromises the success of the project. Rather, its value lies in its capacity to encourage people to co-design their own futures. It is more about joining people that want to create than attracting those that want to buy. Surely, it is the process of creation of alternative that’s been set in motion that is truly significant, even more than the technologies being produced. Furthermore, Open_Sailing manages to reverse the process of co-option, the same way it reverses the effects of threat. Collaborators turn to scientific institutions, corporations, military research, as a useful resource, and then open up the knowledge acquired. This is not a new ‘green design’ product for the consumerist society, it is a spark for a collaborative rethinking of the world.

A conversation between G.H. Hovagimyan and Mark Cooley conducted through electronic mail – January 2008.

MC: Over the years, you’ve had experiences with various authorities that have tried in one way or another to censor your work. I’m interested if you could identify and comment on particular sites of censorship that exist in and around Art institutions and identify some the taboos that tend to generate negative responses from potential censors (curators, board members, sponsors, politicians, and other interested parties).

GH: The most blatant example was a piece called, Tactics for Survival in the New Culture. It was a text piece. I was going to put it in the windows of 112 Workshop (the first alternative space in New York City & the US) in 1974. Since 112 depended on grants from NYSCA and National Endowment for the Arts I was told I couldn’t do the piece because it would jeopardize their funding. I did do the piece later for another exhibition called the Manifesto Show for COLAB (an artists group I was a member of). When I first started working on the internet twenty years later in 1994 I put the piece up as a hypertext work. I have also updated it from a manifesto to an interactive textual maze http://www.thing.net/~gh/artdirect . The piece is not cute. It deals with the dark side of the American psyche. It is a meditation on the psychological states that would bring one to be an anarchist. It is a New York Punk Art piece. Punk was a rebellion against the fake hippy utopian art that was being produced at the time. That type of art is still being produced. It gets a lot of funding because it is uncontroversial.

There are of course several ways to censor artists for example the simplest is to not include the work in an exhibition or ask the artists to alter the work to make it more acceptable. This happens to me a lot in the US. Several of my artworks in particular my net.art works have sexual content. One of my first internet pieces Art Direct/ Sex Violence & Politics was always raising hackles because of the sexual content. It was not included in several major internet shows because the museums were afraid that children would come upon the images and they would be liable. In this case both the government and the institution censored the work. In France the same work was featured in a centerfold of Art Press magazine in a special issue on techno art.

People who censor are often corporations flexing their muscle. One of the pieces in Art Direct … called BKPC used Barbie, Ken and G.I. Joe dolls. At some point the isp host, *the thing* received a letter from Mattel toys demanding that the site be removed for violation of copyright. I had to get a lawyer and send them a letter saying it was fair use and for them to back off. Luckily the people at the thing were not intimidated by Mattel so the site stayed up. By the way BKPC is about interracial sex so it makes people uncomfortable or it’s titillating. When I showed the physical work in a Christmas showed called Toys/Art/Us, I was asked by the curators to make sure that children could not view the art work. I did this by mounting the works in glassine sleeves on a podium that could only be seen by standing adults. I was lucky the curator wanted to show the work and was willing to work through the problem with me. In other cases the curator would not be that imaginative and simply shy away from showing anything that was vaguely controversial.

Another case of censorship was the Whitney Art Port an online new media projects gallery. I did a piece called Cocktail Party that featured synthetic voices in conversations as if they were drunk and at a cocktail party. I was asked to remove three sequences because of their sexual content. I wanted so much to be included in this project and the curator was a friend that I altered the piece, removing the offensive parts. The curator was afraid that the corporation would stop funding the project if I offended them with my overt content.