Featured image: Stern, Body Language

Interactive Art and Embodiment: The Implicit Body As Performance by Nathaniel Stern. ISBN 978-1-78024-009-1 (printed publication), Gylphi Limited, Canterbury, UK, 2013. 291 pp., 41 Colour Stills.

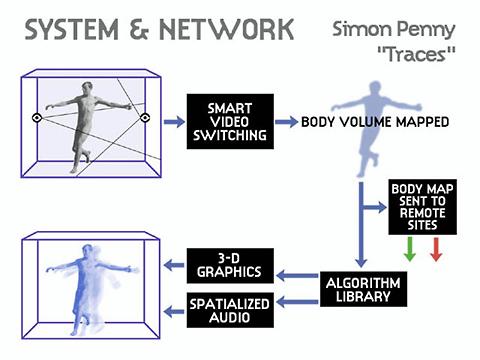

Earlier this year, I had the good fortune to sit in on a talk given by Simon Penny on May 6th 2014 at the University of Exeter. Penny, not unlike Nathaniel Stern, is best known for his praxis, writing and teaching on interactive (and robotic) installations focusing on issues of embodiment, relationality and materiality. So as unorthodox as its inclusion is to start off a review, Penny’s reflections are pertinent here (in this case, Penny’s famous installations Fugitive (1997) and Traces (1999) [1].

The purpose of Fugitive and Traces (if you can say they had one) sought to ‘embody’ virtual reality through multi-camera infra-red sensors, visual models and real-time movements. At that time, Penny’s unique theoretical take was to distance human-computer interaction away from “a system of abstracted and conventionalised signals” to where the user would “communicate kinesthetically”: instead of investigating the non-human or “inhuman” formal qualities of its medium, or some vague VR future that leaves the body behind, the system itself would “come closer to the native sensibilities of the human.” (Penny) [2]

In his Exeter talk, Penny momentarily reflected on a weird and altogether disturbing seventeen year feedback loop. The loop in question relates to how, in 2014, Penny’s early avant-garde ideas and theoretical ambitions have largely been desecrated by their replication in big business. With regard to Traces, Penny cited Microsoft’s Kinect as being the most salient example of this desecration: Kinect’s technology – marketed for the Xbox console brand – carries within its insidious techniques the ability to also “communicate kine[c]thetically”, but do so within pre-packaged, patented, IP-driven, focus-grouped-out-of-existence, commercial vacuities of gamer experience.

As an early practitioner and developer of these technologies, Penny was somewhat visibly infuriated with this, and understandably so. For him, it unintentionally reduced his aesthetic experimentation, philosophical insight, technological futurity and theoretical complexity into consumer speculation for the technology market, commandeering the tech but without the value. It transposed the artistic technological avant-garde necessity of Traces into a flaccid ‘tech-demo’ demonstration of novelty limb flailing and high-end visuals devoid of anything. It was, Penny lamented, “a very weird situation” to be in. Part of that weirdness has to do with the fact that Penny hadn’t done anything especially wrong, because there wasn’t any tangible aesthetic qualities that separated his pioneering work from Microsoft’s effort. Neither had Penny’s work brought financial success with its value intact (because its value wasn’t patentable). Instead technological development had overwritten the aesthetic value of Traces, trading technological obsolescence with aesthetic obsolescence.

Penny’s retroactive predicament is not unique in the history of digital art: for all the visionary seeds of potential in Roy Ascott’s legendary networking project, Terminal Art (1980) we now recognise how those salient characteristics have somehow ended up as Skype or Google Hangouts. Still in the 80s, one might evoke Eduardo Kac’s early videotext works (1985-1986) where visual animated poems were broadcast on the online service exchange platform Minitel (“Médium interactif par numérisation d’information téléphonique” or “Interactive medium by digitalizing telephone information” in its French iteration): a proprietary precursor to the World Wide Web [3]. The retroactive weirdness accompanying these developments is something I’ll come back to: suffice to say that what counts is the direction (and sometimes hostile return) of infrastructure, not just as the background collection of assemblages artists rely on to experiment with at any historical moment, but the shifting ecological foundations to which technology emerges, affords, and now overwrites such practices. No-one likes to play devil’s advocate and yet one must ask the question specific to Stern’s text: what, or maybe where, is the tangible point at which ‘art’ becomes historically valued in these works, if that latent aesthetic potential becomes just another market for a series of Silicon Valley, or startup conglomerates?

——–

Nathaniel Stern’s Interactive Art and Embodiment establishes two first events: not only Stern’s debut publication but also the first of a new series from Gylphi entitled “Arts Future Book” edited by Charlotte Frost, which began in 2013. All quotations are from this text unless otherwise stated.

Stern’s vision in brief: in order to rescue what is philosophically significant about interactive art, he justifies its worth through the primary acknowledgement of embodiment, relational situation, performance and sensation. In return, the usual dominant definitions of interactive art which focus on technological objects, or immaterial cultural representations thereof are secondary to the materiality of bodily movement. Comprehending digital interactive art purely as ‘art + technology’ is a secondary move and a “flawed priority” (6), which is instead underscored by a much deeper engagement, or framing, for how one becomes embodied in the work, as work. “I pose that we forget technology and remember the body” (6) Stern retorts, which is a “situational framework for the experience and practice of being and becoming.” (7). The concepts that are needed to disclose these insights are also identified as emergent.

“Sensible concepts are not only emerging, but emerging emergences: continuously constructed and constituted, re-constructed and re-constituted, through relationships with each other, the body, materiality, and more.” (205)

Interactive Art and Embodiment then, is the critical framework that engages, enriches and captivates the viewer with Stern’s vision, delineating the importance of digital interactive art together with its constitutive philosophy.

One might summarise Stern’s effort with his repeated demand to reclaim the definition of “interactive”. The term itself was a blatantly over-used badge designed to vaguely discern what made ‘new media’ that much newer, or freer than previous modes of consumption. This was quickly hunted out of discursive chatter when everyone realised the novel qualities it offered meant very little and were politically moribund. For Stern however, interactivity is central to the entire position put forward, but only insofar as it engages how a body acts within such a work. This reinvigorated definition of “interactive” reinforces deeper, differing qualities of sensual embodiment that take place in one’s relational engagement. This is to say, how one literally “inter-acts” through moving-feeling-thinking as a material bodily process, and not a technological informational entity which defines, determines or formalises its actions. A digital work might only be insipidly interactive, offering narrow computational potentials, but this importance is found wanting so long as the technology is foregrounded over ones experience of it. Instead ones relationship with technological construction should melt away through the implicit duration of a body that literally “inter-acts” with it. In Stern’s words:

“…most visually-, technically-, and linguistically-based writing on interactive art explains that a given piece is interactive, and how it is interactive, but not how we inter-act” (91)

Chapter 1 details how aesthetic ‘vision’ is understood through this framework, heavily criticising the pervasive disembodiment Stern laments in technical discussions of digital art and the VR playgrounds from the yesteryear of the 90s. Digital Interactive Art has continually suppressed a latent embodied performance that widens the disembodied aesthetic experience towards – following Ridgway and Thrift – a “non-representational experience.” Such experiences take the body as an open corporal process within a situation, which includes, whilst also encompassing, the corporal materiality of non-human computational processes. This is, clearly, designed to oppose any discourse that treats computation and digital culture as some sort of liberating, inane, immaterial phenomenon: to which Stern is absolutely right. Moreover, all of these material processes move in motion with embodied possibilities, to “create spaces in which we experience and practice this body, its agency, and how they might become.” (40) To add some political heft, Stern contrasts how the abuse of interactivity is often peddled towards consumerist choice, determining possibilities, put against artistic navigation that relinquishes control, allowing limitless possibilities. Quoting Erin Manning, Stern values interactive art’s success when it doesn’t just move in relation to human experience, but when humans move *the* relation in experience (Manning, 2009: 64; Stern, 46).

Stern’s second chapter moves straight into a philosophical discussion denoting what he means by an anti-Cartesian, non-representational, or implicit body. Heavily contexualised by a host of process, emergent materialist thinkers (Massumi, Hayles, Barad), Stern concentrates on the trait of performance as the site of body which encapsulates its relationally, emergence and potential. The body is not merely formed in stasis, (what Stern dubs “pre-formed” (62) but is regularly and always gushingly “per-formed” (61) in its movement. Following Kelli Fuery, the kind of interactivity Stern wants to foreground is always there, not a stop-start prop literate to computer interaction, but an effervescent ensemble of “becoming interactive” (Fuery, 2009: 44; Stern, 65). Interactive art is not born from an effect bestowed by a particular medium of art making, but of “making literal the kinds of assemblages we are always a part of.” (65)

Chapter three sets out Stern’s account for the implicit body framework: detailing out four areas: “artistic inquiry and process; artwork description; inter-activity and relationally.” (91) Chapters four, five and six flesh out this framework with actual practices. Four considers close readings of the aforementioned work of Penny together with Camille Utterback merging the insights gained from the previous chapters. What both artists encapsulate for Stern is that their interventions focus on the embodied activities of material signification: or “the activities of writing with the body” (114) Utterback’s 1999 installation “Textrain” is exemplary to Stern’s argument: notably the act of collecting falling text characters on a screen merges dynamic body movements with poetic disclosure. The productions of these images are always emergent and inscribed within our embodied practices and becomings: that we think with our environment. Five re-contextualises this with insights into works by Scott Scribbes and Mathieu Briand’s interventions in societal norms and environments. Six takes on the role of the body as a dynamic, topological space: most notably as practiced in Rafael Lozano-Hemmer. Chapter seven I’ll discuss near the conclusion: the last chapter shortly.

Firstly, the good stuff. Interactive Art and Embodiment is probably one of the most sincerest reads I’ve encountered in the field for some time. Partly this is because the book cultivates Stern’s sincerity for his own artistic practice, together with his own philosophical accounts that supplement that vision. His deep understanding of process philosophy is clearly matched by his enthusiastic reassessment of what interactive art purports to achieve and how other artists might have achieved it too. And it’s hard to disagree with Stern’s own position when he cites examples (of his work and others) that clearly delegate the philosophical insights to which he is committed. One highlight is Stern’s take on Scribbes’ Boundary Foundations (1998) and the Screen Series (2002-03) which intervenes and questions the physical and metaphorical boundaries surrounding ourselves and others, by performing its questioning as work. This is a refreshingly earnest text, proving that theory works best not when praxis matches the esoteric fashions of philosophical thinking, but when art provides its own stakes and its own types of thinking-experience which theory sets out to faithfully account and describe. Stern’s theoretical legitimacy is never earned from just digesting, synthesising and applying copious amounts of philosophy, but from the centrality of describing in detail what he thinks the bodily outcomes of interactive art are and what such accounts have to say: even if they significantly question existing philosophical accounts.

Stern leaves the most earnest part of his book towards the end in his final semi-auto-biographical companion chapter called “In Production (A Narrative Inquiry on Interactive Art)”. This is a snippet of a much larger story, available online and subject to collaboration [4]. Here, Stern recounts or modifies the anxiety inducing experience of being a PhD student and artist, rubbing up alongside the trials of academic rigour, dissertation writing and expected standards. Quite simply, Stern is applying his insights of performative processual experience into the everyday, ordinary experiences faced by most PhD students in this field, and using it to justify a certain writing style and a sense of practice. It’s an enjoyable affair – in large part because it outclasses the dry scholarly tone usually associated with writing ‘academically’, elevating imaginative, illuminating redescriptions for how the experiences of interactive art broadly hang together rather than relying on relentless cynical critique. And most of that is down to Stern’s strong literary metaphorical technique for grounding his vision, perhaps even more effectively than the previous chapters.

Yet earnest experiences aside, there are two problems with Stern’s vision which, in my eyes, leave it flawed. That isn’t a bad thing: all visions are flawed of course. That’s why the similarities between art and philosophy feed our heuristic, academic compulsion to come up with them and debate: well, that and sometimes the most flawed can end up being the most influential. Such flaws only arise in relation to what Stern thinks is valuable in interactive art, and to the extent that the intervention posed may require readdressing. The flaws in question are composed from two different angles, but stem from one objection. The first is philosophical, or at least a problem pre-packaged with relying almost entirely on relational ideas of embodied emergence. The second is more tied to infrastructure and technical expropriation as outlined in Penny’s predicament given from the outset.

In his introduction, Stern makes clear that this is an “art philosophical book” (4), not a philosophy of art as such: only one that “understands art and philosophy as potential practices of one another” (4). Following Brian Massumi, philosophy “tells us the stakes”, whilst “art brings those states to the table” (5), such that the type of art he values and constructs, (digital interactive art) is precisely that which melts away in its interactive encounter when constructed as work. Later on we discover that interactive art “interrupts relationality” (66), making present an “intervention that brings a situated moving-thinking-feeling to a higher power.” (66) Further on, interactive art does something else, when it “intensifies features of […] the ongoing transformation of the ‘living’ body”, and “gifts us with a state to practice being and becoming.” (73) Reflecting on the infamous Bourriaud/Bishop relational aesthetic ruckus a decade ago, Stern outlines how they focus on the explicit body (82) (how we understand ourselves or challenge explicit social/economic positions in the world), whereas artworks which privilege the implicit body have us “encounter how we move, transform, and are (continuous)” (82) in the world. The former takes on the materiality of social relations, the latter (endorsed by Stern) takes on the whole materiality of “embodied relations” (83). And again to reiterate, art operates as “the practice of contemporary philosophies, where we investigate, and further research on, embodiment and relationally together.” (83).

Now, one should admire how Stern blends philosophy and art praxis together precisely by not shoehorning authoritative philosophical accounts into art praxis where they aren’t needed. This works, precisely as the ontology expressed here actively resists such authoritative accounts as well as being cemented with the sort of sincerity with which Stern has such a keen literary grasp. More importantly, Stern cites works which seem to fit the stakes of his ontological conviction perfectly.

However the reliance of process-based philosophy dampens exactly how these works intervene to bring about the values he so desires. The simplest objection comes from asking how Stern might value anything at all, if our entire relational embodiment with the world is constantly in process – or that “[b]odies and matter are change” (220) – and must be always affirmed as such: why should every process and every bodily interaction be affirmed? Moreover why is it art’s place to give primacy to the ontological events of bodily material change?

This is one of the key infrastructural problems that surface, once a theory of art totally subscribes to a process-based ontology, let alone one focusing on embodiment: why should an artist like Stern feel compelled to present an intervention in the first place? If the dominant ontological movement of interactions is a becoming-event, by what standard or eruption should interactive art be said to work on? If, as Stern believes, “the interactive process in interactive work is the ‘work’” (159), it becomes unclear what value interactive artworks are purported to convey, if that process is all there is. To say that embodied processual events make the work “work”, because they underscore our situational intelligibility (or make it effective – so to speak) speaks nothing of what differential criteria should apply to make that aesthetic intervention intelligible. To hazard a guess, the problem is one of articulating how convention exists in a process ontology: because if everything is always emerging as an interactive event of change, the act of rupturing or intervening in convention becomes a real problem. The criteria for valuing these important works is only affirmed it seems, because every process is already affirmed: and if that’s the case you don’t need artists to make an intervention – there is no intervention required, other than the events that already exist, as change in themselves. To put it another way: why should (and how can) a work effectively gift us heightened states of being and becoming, if our entire situational relationship with the world is already situationally related in being and becoming?

I am reminded of Adrian Johnston’s 2001 review of the newly republished English translation of Dominique Laporte’s History of Shit (first published in 1978). Whereas most Foucaultians and Althusserians were disconcertingly vague in pointing out the concrete material conditions for subjectivity and economical production, Laporte boldly contended that the genealogical hypothesis to all modern civilisations was tied to one concrete material condition: the infrastructure of bodily waste management, or, the desire to control and sublimate our need to defecate. In his usual Žižekian repartee, Johnston suggested that Laporte’s bizarre history of modernity implicitly accepted the anti-Cartesian embodiment thesis (that cognition cannot be separated from the actions of the body), but pushed its logic to the end. That for all the affirmative, encompassing, sensual, emergent, potential images embodiment philosophy prefers to agree and discuss, it completely ignores one of our central and basic bodily requirements: to excrete our bodily waste or fecal matter, and remove it from sight and smell (and we don’t need to remind the reader of art’s fascination with this area).

Whilst Johnston’s tongue was firmly planted in his cheek, he did happen to put a psychoanalytical finger on the central problem with process based embodiment. That often enough, sincere accounts of embodiment designed to affirmatively depict and encompass implicit environment material engagements leave behind an unacknowledged stain: one which says more about these accounts than their proponents actually do. And it is precisely because Stern focuses on the most aesthetically agreeable areas of bodily engagement in interactive art, that something as habitual and ritualistic as the excretion of digested matter, or the infrastructure of sewage networks exposes that image.

In terms of materiality this is doubly important. Laporte’s intervention brings into conflict two competing performative materialisms which disclose our own bodily relationships with non-human processes (in this case, computational and networked material): the first is Stern’s own account of the material body as some sort of ‘nebulous material’ which is always emergent, lived, relational and thinking with its own engagement in the world of humans and non-humans. The second is Laporte’s material body seen as ‘brutal material’ – an explicit input-output, complex, evolutionary processing machine, strictly determinate and bounded in its biological function. Despite Stern arguing earnestly for the nebulous form, it doesn’t appear to me that he can hold off the brutal form, or at least prevent the latter from antagonising the former. And often enough, this happens because Stern’s accounts of embodiment, and the philosopher’s accounts he relies on, are already meant to be nebulous in themselves.

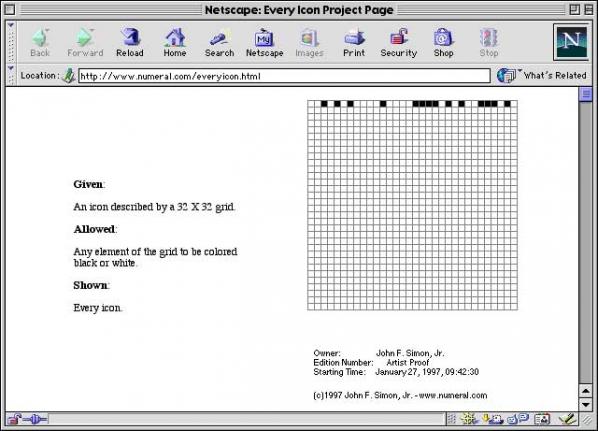

This logic unravels by chapter seven, when Stern expands the implicit body framework to analyse other examples of new media art which aren’t preoccupied with bodily participation to work, as work. He terms this “potentialized art” (206) where “audience members do not *make* the work directly through their interactions (207) but are subject to visual performances of potential movement and relation mediated by generative computation and networks. In citing Gordan Savičić and Jessica Meuninck-Ganger – amongst others – Stern argues that these ongoing performances harness generative information participating in embodiment relations, and invite metaphorical sensory change and bodily movement (in the case of Savičić’s performances, quite literally inflicting pain and suffering onto his own body using network data and social media).

However when Stern cites John F. Simon. Jr’s infamous work Every Icon (1997), (227 – 230) (a cellular automation piece which takes approximately several hundred trillion years to complete) it becomes clear to me that the aesthetically agreeable areas of embodiment start to break down. It might be that my own reading of the piece is fairly unorthodox [5] (I don’t consider the work to be primarily conceptual for a start), but Every Icon eschews what Stern writes as giving “both the corporeal and incorporeal a present and future presence as time and sign” (230) or something that generates attention to our “sensual and conceptual experience of temporality” (230).

Yet, isn’t it the case that Every Icon is probably one of the least potentialised artworks ever made? It doesn’t actually generate anything, (in the strict sense of unpredictable outcomes from simple rules) it simply enumerates configurations of pixels one by one. Neither can we be said to “feel the potency of several hundred trillion years” (230) than we feel the cold, indifferent execution of a real java applet function to which we are forever limited in experiencing directly. If anything, Every Icon is deliberately constructed to forgo a relation with us.

To conclude: this is perhaps why Penny’s predicament with the Kinect is so stark. To demand, as Stern does, that we treat digital interactive art as setting a stage for examining how we “per-form” with our bodies within media, material, conceptual frames and selves, is no longer enough of a stage to give voice to the technological ecologies we find ourselves in: nor of the art that satisfies intervening in it. Credit must be given to Stern for writing over interactive art’s emancipatory myth of disembodied immateriality, but his endorsement of embodiment only serves to realise that the problem isn’t forgetting to focus on material engagement, but forgetting the cold, hard and brutal materiality of procedural performance of infrastructure, that often moves faster than we do. When Microsoft’s Kinect co-opts all the same values of Traces, it does so not because embodiment is totally flawed, but that bodily movement has now become ecologically implicated in deceptive infrastructure.

Just as Penny’s Traces may once have evoked a renewed attention to moving-thinking-feeling, such engagements are now suitably tracked and are in service of non-transparent infrastructures of geo-social activity, which propagate themselves beyond our sensory engagement, yet paradoxically they also indirectly sustain that ordinary engagement. For example, this is now a world where Google funds a 60tbps undersea cable connecting the West Coast to Japan, in order to propagate the reach of their services. The technological engagement of our bodies cannot be restricted to how we move-think-feel, but now weaves itself within layers upon layers of platforms and pervasive surveillance structures. And I don’t disagree with Stern that the implicit body is, perhaps, deeper than the account I give here. But maybe that’s because the body is also another type of performative infrastructure, tightly bound into other formations that are just as deep, complex and engaged. We now live in a time where digital interactive art has to intervene in the performances of geo-social infrastructure: where our bodies have curiously taken on their self-directing performances, rather than our own.