Robert Jackson continues with a second journey into the realms of Accelerationism and Ordinaryism. Having articulated how Accelerationism merges Enlightenment principles in a supposed age of automation, Jackson interrogates its philosophical roots by suggesting that the core motivation behind its key approach embraces skepticism (even if the explicit method is to reject skepticism in favour of increasing applications of knowledge) – whereas what Ordinaryism suggests (following Cavell) is that skepticism cannot be refuted nor endorsed, only inhabited as a salient vulnerable conditon. The political implications of this division are telling and can be extrapolated through the freedom to Exit (inhuman acceleration) versus the freedom to find ones Voice (Ordinary appeal).

“But who is the authority when all are masters?” (Cavell, The Claim of Reason, p. 180).

For part 1 click HERE.

For part 3 click HERE.

In its philosophical usage ‘skepticism’ [i] hardly surfaces, if at all, in the contemporary Accelerationist lexicon. This is to be expected: as its political aspirations are organised by a cascade of philosophical trajectories designed to either refute skepticism, or as ordinaryism will claim, not bother to take it seriously enough.

Ordinaryism and Accelerationism approach familiar problems, even familiar desires, from familiar starting points, yet ultimately arrive at different conclusions. Most notably the political desire to overcome the intellectual chagrin of postmodern skepticism. Exactly what sort of overcoming is required feeds the conflict put forward: a conflict which has its history in the activity of reasoning as referenced earlier between Wilfrid Sellars and Stanley Cavell’s divulging and unique approaches to post-analytical knowledge.

Part 2 explores the following discord: Accelerationism (specifically its neo-rationalist, epistemic variant) builds a collection of political arguments which in order to work, have to refute skepticism. This is akin to (but not conflated with) the removal of skepticism in political emancipation through the practical competency of conceptual, normative reasoning. Ordinary, everyday experience is only considered as a human constraint that can be overcome or explained by a technological inhuman sovereignty of collective reasoning, where linguistic practice is essentially procedural, explanatory, functional and rule-governed. Alex Williams put it this way in his 2013 essay ‘Escape Velocities’;

Accelerationism in this guise is the project of maximizing rational capacity—the contents of knowledge about the world—and enabling the ramification of the conceptual space of reason… Enlightenment, rather than entailing an edifying reassurance of the humanistic order, instead gradually but irreparably modifies the manifest image of ourselves-in-the-world, stripping back the comforting homilies of humanism to reveal, Terminator-style, the gleaming bones of Sellars’s empty, formalist, rational subject lying beneath.

Ultimately Ordinaryism and Accelerationism want the same outcome though: the progressive aim for a better future in the face of the immediate everyday. But whereas Accelerationism thinks this can be achieved through the ascension of reason, Ordinaryism thinks it can be achieved only by acknowledging reason’s vulnerability. We must attend and attune to a diurnal world and others around us through the emotional exposure of claims rather than the Promethean expanse of the stars. Ordinaryism interrogates this force of Accelerationist reasoning and seeks a romantic alternative located in the epistemic, ethical and aesthetic priorities of responsiveness, alterity, otherness and appeal that are constitutive of the everyday and its fusion with technology. The larger attempt calls for the everyday to be reclaimed whilst surrounded by the purported effects of a ‘knowledge economy’. How is it that everytime we appeal for a new future, we are really appealing for a ‘new normal’?

The diagnosis establishes itself in the role of skepticism: and for Ordinaryists, skepticism cannot be refuted – only inhabited. Epistemic doubt has to be lived and coped with. The Cavellian lesson of the ordinary is that the world isn’t to be known, but to be acknowledged: a viewpoint which, presumably, would make the accelerationist hairs stand on end. But this not to say that ordinary acknowledgement – the everyday in general – is tantamount to political complicity and illusive habit. Ordinaryism only establishes an interest in what Cavell terms the eventual everyday, against the actual everyday of common sense, responding to the ordinary as if it appeared to us for the first time. Our relationship to others, and of the world, isn’t an exercise of philosophical skill which can be explained or solved because of an intellectual error, with its ambiguities swiped aside or viewed as insufficiently limiting. Nor is this condition indicative of ‘ordinary beliefs’ in public consensus whilst experts and technicians manipulate the structural groundwork behind the scenes: it is central to the democratic possibilities of all political activity. Bringing Cavell’s views of skepticism into focus allows us to acknowledge that politics is not well-serviced from a detached epistemological point of view: or an inhuman, impersonal space of reasons. One might wish to ask, why should any appeal to the strange tendencies of the inhuman take priority, when the familiar is equally as strange?

And following Cavell, the ‘ordinary’ in this view, is taken from the ordinary language philosopher’s commitment to reasoning. It appeals to “what we should say when..”: that any ordinary voice, what we ordinarily say, ordinarily mean, ordinarily know, has the same authority as any other when responding to what a situation calls for. Moreover, with ordinary language philosophy’s technique (in particular its leading practitioner J.L. Austin), one can simply take an instance of a word, used with certainty (I am free, I know) pick out all the ordinary, ambivalent uses philosophers don’t bother addressing, only to reveal as if for the first time, what it is we ordinarily accept everyday.

It’s a radical challenge that has a loose origin in Romanticism, but can be hinted at through punctuated periods of twentieth century philosophy. However the idiosyncratic musings of Wittgenstein interest us here, or at least those brought into fruition by Cavell’s masterpiece The Claim of Reason building towards later work on Emerson. Cavell remains indispensable here insofar as his collective, idiosyncratic view imparts a view of language, justification and reasoning based on the never-ensured acknowledgement of one other (and the claims of what we ordinarily say through one’s voice), in each specific and singular case of reasoning. This will be opposed against a neo-rational appeal to a universal inhuman force, waging on some quasi-guarantee that reason is alien, determinate and self-correcting.

In the space given I won’t be able to replicate the philosophy here at its most sophisticated, so we’ll have to settle for a more general level of enquiry that collates various, repeated aspects of the conflict involved. The remarks put forward will hopefully show why a Cavellian normative ‘Voice’ or ordinary appeal is an indispensable political tool, only because it treats skepticism seriously as an ordinary task in a world of increasing automation, not to superseded by a warped view of technology that can overcome it. Ordinaryism sheds a Cavellian insight that our relationship with technology fundamentally pivots on living our skepticism: inhabiting our condition, acknowledging our vulnerability, making ourselves intelligible to others, desiring an intimacy with things and establishing a voice to do so. The additional requirement here, comes to terms with the notion that skepticism isn’t a unique feature of ordinary language projected onto the world (as Cavell held), but is now operationalised in machinic systems. This is explicitly against an accelerationist insight, that machines operationalise the ascension of inhuman reason.

The problem is that Accelerationist reasoning simply refuses to consider skepticism as a problem, ridicules the everyday and instead pines for an inhuman, rule-bound determination of normative governance, which the ordinary cannot achieve. By doing so, it appears unconcerned with political dangers once the voice of others is rendered insufficient: that we could fail to acknowledge others, unwittingly presenting our relationships to knowledge and of other minds as unproblematic.

This unorthodox schism on reasoning can be exposed into a more contemporary technical conflict vying for political, philosophical and technological priority – call it, the freedom to Exit (inhuman acceleration) versus the freedom to find ones Voice (Ordinary appeal). The claim being that all political repercussions of Exit versus Voice pivot on whether you can refute skepticism, or inhabit its condition.

Over two years ago, Stanford University lecturer and entrepreneur Balaji S. Srinivasan delivered a speech at the 2013 Startup School event, entitled “Silicon Valley’s Ultimate Exit” (Transcript here). His talk was noteworthy for galvanising Silicon Valley cohorts into a usual online futurist catatonic stupor. But like all effective presentations Srinivasan delivered one simple, established idea into a contemporary setting and did so with honesty and gusto. Silicon Valley’s seemingly unstoppable knack for disrupting nearly all forms of cultural production and communication can be unpacked from an insight in 1970s political science.

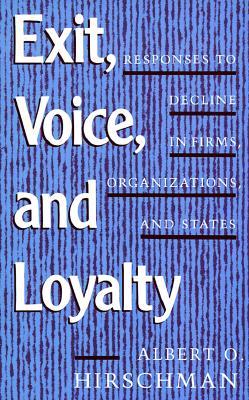

Srinivasan paid tribute to the landmark libertarian 1970 treatise “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organi[s]ations, and States” by Albert O. Hirschman, in which the author stated the following economic conjecture: When any particular form of human system culturally designed to offer a service (a business, charity, government, country, state, school, etc.) experiences a decrease in quality, they have two options for freedom; either Exit or Voice. Put simply, Exit is the attempt to withdraw completely from the relationship provided with the aim of joining or starting up another, whereas Voice gives the customer the right to reform the existing relationship through protest and complaint.

Hirschman used these two options as a prism for opening up a range of economic and political outcomes that encapsulate ones freedom, equally emphasising that such models were mutually exclusive, operating in a parallel stop-start fashion. He understood Exit to be exclusively libertarian where freedom was guided under the economic freedom of the market, where decline could be corrected by ‘better’ services. Voice became the political freedom to confront existing decline by reforming the system within. Unpacked into differing global contexts, Exit vs. Voice shifts into multiple flavours of freedom, emanating from the same source. For a consumer, Exit manifests itself as the freedom to take your business elsewhere, whereas Voice is sending off a complaint form. For a country, Exit becomes emigration whereas Voice becomes the democratic right to vote. In the case of lobbying, Exit expresses itself as the think tank, whilst Voice emerges as the grassroots protest.

However Srinivasan took Hirschman’s options and gave the distinction a new technological edge relatable to an age of platforms, code, startups and disruption. Srinivasan suggested that Exit is a meta-concept which Silicon Valley has implicitly adopted, subsuming Voice without eliminating it (and perhaps even amplifying the latter). It is the hidden gear behind the Valley’s dominance, from various startup successes to the inherent properties of code itself. He cites the fact that Larry Page and Sergey Brin could never have reformed Microsoft from within, and so had to found Google by attaining the freedom to exit Microsoft completely, taking the sustained knowledge of their peers and independently crafting something smarter and better. Similarly, in software engineering if Voice operates as a patch designed to reform existing functional problems, Exit is the fork designed to splinter an existing platform of ineffective decline into a separate, and (presumably) more effective one.

But Srinivasan’s talk was essentially in support with ‘ultimate exit’ – the idea that the United States itself was completely beyond libertarian reform, and that Silicon Valley would in the next 10 years have to secede, and launch its own independent platform if it wanted to maintain freedom. Srinivasan’s rationale (which has solidified its popularity since 2013) is that if you can do it with a startup why not an entire country? It’s not exactly a pipe dream wither. A failed startup called Blueseed already sought funding in order to attempt such a feat, but it was eventually postponed. Blueseed was the closest attempt at creating an ultimate Exit, where a purposely built cruise liner, sailing twelve nautical miles from San Francisco, would allow entrepreneurs to create their own businesses without the need for a U.S work visa. Earlier still, a 2005 startup called SeaCode promised something similar, but similarly folded due to insufficient funding.

In the eyes of the Valley though, the Exit strategy has successfully challenged existing industries anyway; including Hollywood (through Netflix), print and television outlets (through social media), city transport (through Uber), currencies (through Bitcoin and Blockchain), healthcare (The Quantified Self movement), and even simple objects (3-D printing). Before the backlash hit the fan, Srinivasan’s foresaw that the only future worth betting on would involve building “an opt-in society, ultimately outside the United States, run by technology.” Who is John Galt? Presumably Balaji S. Srinivasan.

Randian fetishes aside Exit versus Voice is a clever forced choice. It’s designed to organise a schism in contemporary political thought where cultural activities and labour are increasingly wedded to automation: from casual acts of ordinary communication, to the darkest depths of hidden encryption. It’s a schism which the theoretical movement of Accelerationism is borne out from, despite the clear difference of its political goals and the varying flavours bundled with its name. Replacing Srinivasan’s libertarian freedom for a hard left emancipatory stance, Exit is now construed as engineering a post-capitalist exit, and ‘opting-out’ becomes inventing and repurposing technological infrastructure towards emancipation without losing any of the inhuman significance that got it there.

What is it however that philosophically separates the contemporary Left accelerationist position from previous iterations unable to grasp the future, or have resisted such attempts? We are of course reminded of such post-structural flights of fancy, (accelerationist musings of Lyotard, Deleuze and Guattari) to the experimental Cybernetic Cultural Research Unit (CCRU) whose famous figureheads included Nick Land & Sadie Plant. As many have already written, Land has become the quintessential prophet of the contemporary ‘Exit’ strategy (both in his early philosophical work, and later activities) understanding capitalism to be the ultimate engine of inhuman freedom. If our manifest fate is destined to head towards a technological singularity, it has only been put on ice because of meddling Marxists and (in his eyes) a dribbling progressive State. Having reorganised his views into neo-reactionism (NR-x), (which Srinivasan’s talk contributes to and in no small part, influentially gravitated a great number of libertarians towards), Land has one goal: the full realisation of ultimate exit. As Park MacDougald put it last year, Land’s;

Laissez-faire, in this view, is doomed to failure as soon as it’s up for a vote. Rather than accept creeping democratic socialism (which leads to “zombie apocalypse”), Land would prefer to simply abolish democracy and appoint a national CEO. This capitalist Leviathan would be, at a bare minimum, capable of rational long-term planning and aligning individual incentive structures with social well-being (CEO-as-Tiger-Mom). Individuals would have no say in government, but would be generally left alone, and free to leave. This right of “exit” is, for Land, the only meaningful right, and it’s opposed to democratic “voice,” where everyone gets a say, but is bound by the decisions of the majority — the fear being that the majority will decide to self-immolate.

Shockingly, Land’s NR-x demands the elimination of democratic voice altogether because, in his view, economically and socially effective governments legitimize themselves eschewing any appeal for a democratic voice. There isn’t any need for a voice if, like a commercial service, you can just exit your government and join a better one. So long as the functional technocratic inhuman is maximally realised there can be no room for moralism, sentimentality or suffering, for these are the very human traits which hold back our genuine freedom. Bending the market to fit human empathic needs will be futile. The sustained requirement for humans to lend a voice of political appeal is simply too ineffective to halt the inhuman onslaught of capitalist acceleration.

Cemented into the freedom to Exit is the implicit determination that all global technological progress (and its inherent possibilities as production) is bound up with the invisible, impersonal rigour of inhuman market competition, which democratic voice has little hope of addressing, let alone overthrowing. In Land’s view, capitalism is akin to an inhuman non-conceptual alien automatically programming human behaviour in order to drive it forward. This strange, foreign compulsiveness is integral to our dystopian future and Land’s job is to let the tap run (or more accurately, don’t pull the charger out).

So with Land’s current brand of libertarianism leaning more to the right than someone whose right leg has just been blown off, the political ground to develop a Left accelerationism has been given renewed impetus. As Peter Wolfendale previously pointed out, both positions jointly agree that capitalist production and modern developments of social justice are utterly incompatible, and the site of their incompatibility combined with technological expertise is what motivates both to conceive of an Exit: but crucially the discord between them comes from which set of principles should be exited from, and what sort of freedom is called for;

The right thinks that the accelerative emancipatory force is nothing other than capitalism itself, whereas the left thinks that capitalism is an adaptive and plastic obstacle suppressing a deeper emancipatory dynamic. It is in essence a disagreement about freedom: what it is to have it, what it is to enhance it, and whether there is anything we can do about it.

What both forms of freedom inhabit is to construct an exit from the limitations of the current status quo entrenched in reaction, resistance, refusal and reform. If the force of ‘Exit’ is what both movements share, then they also share the same schism of opposing Voice. And in one name or another, this is exactly what Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams have dubbed ‘folk politics’: political methods which eschew inhuman knowledge, global reach, feedback and technological infrastructure favouring instead outdated methods of reform, simplicity, horizontal plurality, immediacy and reactive protest (the 2008 Occupy protests being one example of many). In short, politics that might be associated with the demands of Voice. They may not wish to call it Voice, or be opposed to Voice democratically, and might even propose that it has some sort of place in contemporary political struggle. However, their opposition to a certain form of phenomenological immediacy in authentic resistance (which Voice might certaintly inhabit), carries all the connotations of leftist action they find strategically moribund. Reform and resistance are no longer the sole legitimate leftist options to overcome capitalism.

Their logic is two fold – 1.) reforming the capitalist system through protest, localism and critique alone has become useless at furthering leftist goals, often resulting in unashamed defeatism. Human acts of immediate protest and localism are no longer any match for the long term planning of inhuman complexity that global capitalism has become. The left simply sets itself up to fail.

2.) In light of this failure, contemporary leftist politics has a choice: either reduce political action to a relatable human local level, or embrace complex conceptual mediacy of capitalist process. In adopting the latter, the technological tools at our disposal afforded by capitalism must now invent alternative platforms repurposing leftist change, rather than chastised as oppressive, skeptical limits inherent to it. The left can no longer solely rely on ‘having a voice’ which appeals to habitual sit-ins and sporadic acts of resistance: it must invent alternative methods of infrastructure that will eventually abandon the need for capitalism, overcoming leftist resistance and reform completely (think André Gorz, but with Big Data and Apps).

The output of that challenge operates through various interlocking projects:

—Political theories for how a post-capitalist world that abolishes work can not only be made intelligible but be feasibly engineered (see Srnicek and Williams in their recently released publication ‘Inventing the Future: PostCapitalism and A World Without Work’ published by Verso). To be clear Srnicek and Williams entirely abandon the term ‘Accelerationism’, or ‘Left-accelerationism’ not specifically because of disagreement, but to alleviate widespread confusion.

—Renewed commitments to nineteenth/twentieth century cosmicism that manifests in a post-Earth future. Or alternatively treating science fiction as a necessary path towards a real exit (in its absolute form, exiting the Earth). (See Benedict Singleton’s Maximum Jailbreak)

—Regrounded developments in feminist strategies (see the recent xeno-feminist (XF) manifesto), by the anonymous collective Laboria Cuboniks which in their words asks that “Reason, like information, wants to be free, and patriarchy cannot give it freedom. Rationalism must itself be a feminism. XF marks the point where these claims intersect in a two-way dependency. It names reason as an engine of feminist emancipation, and declares the right of everyone to speak as no one in particular.”

—New strategies for art that oppose contemporary art’s global hegemony (See the forthcoming publication ‘On the necessity of Art’s Exit from Contemporary Art) by Suhail Malik. One might see a recent influence in Holly Herndon’s song “An Exit” which is describes Malik’s exit as “rather than act in angry opposition to an existing aesthetic or marketplace, we just walk away, facing towards the future”.

Yet, the lynchpin that passes through these varying outputs has one additional philosophical goal: one that has reshifted the political site upon which inhuman freedom can be realised through an interconnected philosophy beginning to rethink contemporary forms of reasoning, knowledge and rationalism.

What gives the Left accelerationists an injection of substance is not merely repeating Marxist demands that capitalism is an unjust, unequal system which promotes corpulent wealth, but that it primarily holds back the progressive and explanatory capacities of inhuman reasoning and technological progress (or at least that Voice, under this view, can only ever be the immediate starting point for an inhuman ascension).

Simply put, Left-accelerationism recognises both the lack of freedom and rationality and seeks to restore both in a more contemporary guise: the normative aim of constructing political freedom in ever greater inhuman measures. Thus the additional impulsion of Srnicek and Williams’ project stresses that the only method of overcoming capitalism is to self-master our epistemological knowledge of it , in order to apply methods that structure leverage towards rational self-determination. Here one almost tastes the accelerationist contempt for Leftist skepticism, and all of its appeals to doubt that have become complicit in contemporary forms of political action undermining progressive futurist thought. Skepticism for them, only bestows reason with a staggering lack of imagination and of lives that entirely accept the limits of neo-liberal stupor wrought by epistemic immediacy and affirmationist philosophies (distancing itself from the vitalist aspects of Deleuze and Guattari plays a key developmental role here).

The philosophical appeal toward a universal rationalist epistemology supports accelerationism’s desire to reengage with the Enlightenment project, where freedom becomes the binding of oneself to a universal rational rule (that must include and surpass capitalist and economic development) together with an adherence to that rule. More importantly the universalisation required must be a movement of Promethean ascension which promotes, as Williams puts it alongside Srnicek in an interview with Mohammed Salemy: “the idea that through our knowledge of the world and through political struggle, too, we can open new ways of being free that were unavailable to us before.” Inhuman Exit is rescued from the libertarian darkness of the NR-x hand, and into the clutches of unending rigorous collective reasoning. Inhuman freedom is repurposed away from compulsive slavery of alien market forces, to an alien rationality of a free rational subject that might exit from capital. The only alien demand is an inhuman demand to self-master our own possibilities towards rejecting capitalism (towards a post-capitalist future).

Williams has previously suggested that the twin thinkers of epistemic accelerationism are Ray Brassier and Reza Negarestani (whether these thinkers agree is another matter). Both are highly influenced by Land, and both are committed to an anti-skeptical method of gaining knowledge about the world, where the freedom to reason emerges as rule-governed, practical, revisable, autonomous and collective, not reducible to the manifest experience of humanity yet central to its emergence. Their neo-rationalism repeats the enlightenment’s desire to explain and act on the collective determinacy of the human epistemological condition outside any specific context.

The freedom to self-master an Exit lends its the support for a universal rationalist epistemology as enshrined within Sellars pragmatism (as outlined in Part 1 ). In this guise freedom becomes, according to Brassier, “… not simply the absence of external determination but the agent’s rational self-determination in and through its espousal of a universally applicable rule.” For complicated reasons Sellars sets out a pragmatist view of reasoning which is defined by its anti-skepticism as much as its Promethean promise (dependent on which thread of influence you follow). What makes such freedom a feature of pragmatism is that rationality is understood as an inherently social linguistic activity as well as a rule-based resource for expanding collective knowledge. Freedom through reasoning is grounded in essentially public and social normative practices of communication, that account for the correctness and incorrectness of ordinary linguistic usage and function. The accelerationist motivation is compelled by a pragmatist sensibility that rationality is founded by the capacity of a community to ‘agree in’ statements and judgements as normative commitments and entitlements. This domain from which freedom resides, and where it can be emancipated from, lies in a shared conceptual framework of utility.

The notion that human creatures are defined by living in a normative space of reasons has obvious overlapping concerns with the origins of philosophy, but only really found its teeth in the Enlightenment. The idea that I, as a rational subject can apply a certain concept means I must be committed to or bound by certain consequences. This can be traced through Plato and Aristotle, although the history takes its initial cue from Kant who understood human concepts to be uniquely and fundamentally normative, despite their finite status. Hegel then builds on Kant’s normative insight, eschewing the acknowledgement of finitude, by showing how freedom emerges from normative constraints inherent to discursive social statuses. Or putting it differently, developing an insight that the creation and generation of ideas and concepts arise in a shared normative medium. Freedom is thus, socially expressive, constitutive of norms and rules that already govern and constrain it, yet also subject to generative possibilities which it entertains. As Robert Pippin puts it;

… the problem of freedom, and in the Kantian/Hegelian tradition […] means being able somehow to own up to, justify, and stand behind one’s deeds (reclaim them as my own), and that involves (so it is argued) understanding what it is to be responsive to norms, reasons.(Pippin, The Persistence of Subjectivity: On the Kantian Aftermath, 2005, p. 11)

One of the most influential Hegelian ideas that the epistemic accelerationists have adopted (amongst others) is that without any justification, inferred assertion or claim – let alone a political claim – intelligible forms of progressive political action or agency are out of the question. No human communication occurs, principally, within the sole reducible product of a human individual, but as a distinctly social progressive achievement of reason and that ordinary modes of intelligibility have to be cemented in normative commitments of correctness. The job of philosophy is to offer an explanation constitutive of the very normative system it seeks to explain. Recoding these Kantian and Hegelian insights is said to establish and explain the inner workings of what we mean when we say something.

Clearly, the real reason why such Sellarsian normative accounts are useful is that they are characteristic of many philosophical attempts to comprehend language through a systematic and explainable structure, fully applying the force of reason with practices that commit effective conceptual action. It strips the rational subject back until it finds the primitive inhuman, artificial, functional, rational ‘machine’ guiding the system through the freedoms of feedback and function: What Sellars demarcates as the sapient, normative space of reasons (doing something for a reason) is understood to be completely separate from the sentient, causal nature of reasons (doing something because of a reason). Norms of reasoning cannot, like natural laws, suggest what will happen, but instead what ought to happen, and pinpoint shared, rational outcomes that can be correctly drawn from certain assumptions.

Responsibility and recognition cannot make sense outside of its social, discursive emergence, as is the case of any concept whatsoever, for concepts themselves are characteristically normative. Judgements that express knowledge are distinctively responsible and moreover they express themselves as social commitments. Normative claims and reasons are usually understood as not only bearing commitments and entitlements that take place in discursive behaviour, holding others as responsible, relating to an ideal, rule or standard: they are part and parcel of what it is to be a rational subject. Normative claims are taken to be reciprocal recognitions between human creatures who then take other assertions to be reciprocally rational and assertive to normative ideals, and thus expressive freedom is generated and determined. Thought and expression in this light, begins to give us a manifest grip on a non-perceptual world, which isn’t typically manifest (the dual roles of Sellars’ Manifest Image and Scientific Image provide this ‘grip’). The application of the concept, establishes what is correct as opposed to what might be taken to be phenomenally correct (and thus potentially wrong).

No wonder then this view appeals to general artificial intelligence as a futurist necessity, because sapience must be understood as different from the natural order. This is where Sellars’ anti-skepticism becomes obvious: not only reducing all human voice and communication to a primitive, determinate and rule-governed inhuman process which silently determines our linguistic activity, but at the same time, fully unleashing its ability to explain all possibilities of human communication, as well as what it means to freely communicate at all. It is distinctive that this peculiar inhuman force determines how we ought to act, only insofar as we can conceive it – seeing language this way is what demarcates the normative from the naturalistic, acting on norms is dependent on our recognition of them. Voice and speech simply becomes subordinate to this normative demarcation, because what we say is reducible to what can be thought.

This expressive toolkit for establishing a rational grip on non-perceptible systems in the world is necessary for epistemic-accelerationism. Like Land it commits to the idea that intelligence is wholly functional, but not tied to the machine of the free market, but the machine of rationality (which Land abhors). If it is the case that an inhuman grip of capitalism evades human representation, and with climate change becoming an ever greater non-human concern, then the entrenched political tactics of Voice, the task of the human, must embrace the promethean progress of science and technology and ascend our current cognitive resources accordingly. Srnicek thinks we can do this by returning to Fredric Jameson’s cognitive mapping – “the means to make our own world intelligible to ourselves through a situational understanding of our own position.” Other theorists express the same premise, but in different flavours: the field, the plot, the thread, the yarn. All yearn for the same process: the ongoing project to expand our cognitive intelligibility so that the left can master, identify, calculate and classify invisibly complex systems so as to change them for the better.

However, before we start (or try to start) building space programs and hedge funds for the Left there is a problem. Giving up on Voice becomes far too hasty, insofar as the accelerationist view of Voice is inherently predicated on function, it undermines the very intelligibility it desperately craves. There is a greater depth and vulnerability to Voice that must be addressed which stretches further than the quagmires of reform and resistance. If political intelligibility is predicated on problems of knowledge, questions surrounding what happens to political voice appear to be eradicated. So what happens to it? What might take on the form of addressing normative claims which speak on behalf of others? What might be the unintended political effects of “everyone speaking for no-one in particular”. How does this affect the silenced, who wish to make themselves known, rather than ‘being known’?

It’s easy for the epistemic accelerationists to address political authority if reason’s ascension can be established, but the harder questions arise if reason’s authority is primarily established by vulnerability.

[i] – I’m adopting the American spelling of skepticism here, in large part, because it’s easier to quote from Cavell texts for susequent sections.