AS FOUNDER/DIRECTOR OF THE MEDIA ARCHEOLOGY LAB IN COLORADO, LORI EMERSON HAS (since 2009) been surrounding herself with “dead” media technologies in order to help make sense of (and critique) today’s much-hyped alive ones. Being also a scholar and critic of contemporary poetics, she is keenly aware of how such devices are equipped to influence and constrain our writing/thinking.

Emerson’s work celebrates and calls for a “frictional media archeological analysis” aimed at the continual “unmooring” of the accepted conventions of reading and writing. Towards this end, she critiques consumer-oriented trends in computing–trends which unfortunately seek to “efface the interface” in the name of so-called user-friendliness. Montgomery Cantsin conducted the following interview by email upon the release of Lori’s new book, Reading Writing Interfaces (recently published by University of Minnesota Press).

Montgomery Cantsin: First, I want to point out that your new book is part of a series which was founded by Mark Poster, who passed away not too long ago. Can you talk about how your work fits into his “Electronic Mediations” series and what (if any) influence Poster has had on you?

Lori Emerson: Mark Poster has been an underlying, though subtle, influence on my work as I first read him in a graduate seminar I took on “cybercultures” in the mid- to late-90s with the Victorianist and early hypertext theorist Christopher Keep. That class and Poster’s work–his deeply political readings of digital media structures–stayed with me long afterwards. In fact, about seventeen years ago I gave a presentation on “Postmodern Virtualities” in that class and while I have no memory at all of what I said or even what I learned from reading his work back then, it’s remarkable that his opening sentence rings so true to the kind of work I now find myself doing–he writes that “a critical understanding of the new communications systems requires an evaluation of the type of subject it encourages, while a viable articulation of postmodernity must include an elaboration of its relation to new technologies of communication.” And so the point at which I realized I was, to my surprise, writing a political book that meshed together poetics and media studies was the point at which I realized that my work would likely fit in best (or, given its reputation in media studies, I wanted to make my work fit in) with the Electronic Mediations series, especially because of their books on tactical media, glitch and error, as well as the politics of archives and networks. It’s such a thrill and an honor to have my book included in that series.

MC: How did your Media Archeology Lab come about?

LE: I was fortunate enough to have the support of the past director of the Alliance for Technology, Learning, and Society when I was first hired here at the University of Colorado at Boulder in 2008. In 2009, the director, John Bennett, offered me a $20,000 startup grant to build a lab, any lab, that Atlas and English Department students could both use. I then began looking for a way to build a lab that wasn’t just another venue on campus to celebrate the perpetual new in computing and, since I was at the time fascinated with how the Canadian poet bpNichol wrote one of the first kinetic digital poems, “First Screening,” in 1983 using Basic on an Apple IIe, I decided to create a lab that had enough Apple IIe’s to teach bpNichol in a classroom full of 20 English majors. It didn’t take long before I moved on to acquiring Commodore 64’s and then to where we find ourselves now, with a collection of about a thousand pieces of still functioning hardware and software from the mid-1970s to the early 2000s. I also have to admit that the MAL wouldn’t be what it is now if we weren’t flying under the radar of the university for the first three years or so. The relative obscurity of the lab in those early years meant that we had little to no oversight, no one to report to, no metrics or outcomes to adhere to, and so on which meant we were free to be as wild as we wanted.

MC: In trying to explain your book to a friend, I admit I had some difficulty. I found that it was (for me) hard to do without making the subject of the book sound obscure. And yet I feel that the issues raised in the book are actually quite significant/fundamental. …Let’s delve right into the concept of the interface. As you point out, digital interfaces are now being made “invisible” by manufacturers in the name of “naturalness,” and so it is hard now to even point to a modern interface and say “this is an interface.” At one point you quote Alexander Galloway, who defines an interface as a “point of transition.” (In other words it is a sort of boundary?) You also quote Johanna Drucker, who says that a book can qualify as an interface!? …Is it useful here to ask what’s NOT an interface??!

LE: I think that, similar to Marshall McLuhan’s notion of ‘medium’ which he even extended to roads (and then had to endure a couple decades of ridicule from academics), interface can indeed be anything that’s an intermediary between a human user or creator and what is being created. But unlike using ‘medium’, ‘interface’ seems to allow us to focus our thinking on the particular affordances of specific intermediary structures. It’s not especially unusual or even useful to point out that paper is a medium but, by contrast, calling it an interface summons up not only the material qualities of paper (the grain, size, texture, limits and possibilities for inscription) but also pens and pencils along with that crucial point of interaction that’s between–between writer or artist and their materials. But I also suspect that some of the significance of the concept as I’m using is lost when you start from an arbitrary point in the past and think about needles as interfaces for needlework, or rocks as interfaces for etchings or engravings. Instead, ‘interface’ gains traction when we use contemporary notions of it to have a see-saw relationship between present and past–reading contemporary interfaces through past interfaces and vice-versa. In this way, my book is resolutely of the present because I tend not to delude myself into thinking I can have a pure, direct access to the past. Instead, I start with the closed interfaces of the present moment whose manufacturers try to convince us that a closed device is the only way for us to have a supposedly “natural,” “intuitive,” “seamless” experience with our digital devices; I then work my way back in time to reread typewriters and fascicles or handmade books as profoundly open and configurable interfaces but still with their own limitations.

MC: I was delighted to see that the first scholarly name you drop into your text is that of the amazingly awesome Florian Cramer, the second-wave Neoist. You say he importantly identified eight different types of interfaces. Of these eight, the type that you identify as being of particular interest to you is the “human-to-hardware” interface?

LE: I’m interested in thinking about how certain (largely profit-driven) decisions about interfaces for human-computer-interaction fundamentally affect the human user–determining their access to information along with what and how they’re able to create. This uneven distribution of power between user and digital computer is most obvious when we start to think about why the keyboard/screen/mouse interface has become the only way for us to interact with our machines or when we look at the history of how a particular notion of the Graphical User Interface was used to advance an ideology of the user-friendly. While I am obviously quite dedicated to certain aspects of media archaeology that believe in the value of looking at the operational undersides of machines and the ways in which these machines can now operate quite independently of humans, in Reading Writing Interfaces I’m most concerned with how humans are now almost totally unable to think outside of the current dominant paradigm in computing. This is why I’m less interested in hardware-to-hardware configurations and more interested in the space between human and hardware–as well as software.

MC: I like how you point out that the closed interface can be a sort of metaphor for ideology (‘that which we are not aware of’). This part of the book blew my mind and I’d love it if you could expand on this here.

LE: I’m fast and loose with how I use ‘ideology’ but, after going through every issue of Byte magazine from the late 70s through the mid-1980s after the release of the Apple Macintosh–mostly just to see what I’d find–I became convinced not even that contemporary computing interfaces are metaphors for ideology but that they are themselves expressions of an ideology. Somehow what was at first a battle between competing philosophies in the 1970s–between a model of computing based on openness and a model of computing based on a closed interface for the sake of a very particular notion of user friendliness–gradually turned into an all-out marketing campaign by Apple that was so successful users/consumers are barely even aware of other possible versions of computing. These closed interfaces have become so familiar, so accepted as the so-called ‘natural’ way for users to access their computers, that we are mostly utterly unable to imagine any other alternative. Over and over again, we’re told: “Computers are only getting easier, more intuitive, more natural to use!” Or so the story goes, until you either try to understand how exactly our digital devices work. Or until you try to create outside of a corporation’s rigid developer guidelines. Or until you come up against the impossibility of working with a closed device whose “seamless,” “natural,” “intuitive” user interface doesn’t in any way conform to your own sense of nature or intuition and can’t be rebuilt, remade, or reassembled in your own image because in computing words like “seamless” and “natural” are code for “closed.”

Something I’d love to research more is how this ideology of invisibility is not a reflection of a particular aspect of capitalism (as I thought when I wrote Reading Writing Interfaces) but is actually one of the key underpinnings of a capitalist economy. I recently learned from reading Kirstyn Leuner‘s dissertation that the diorama–which emerged in the 1820s in Paris not coincidentally at the same time as early industrial capitalism began to get its legs (and only twenty years before Marx would move to Paris and begin formulating Capital)–was also produced and marketed as a “magical” device whose inner workings were kept hidden from viewers in the interests of providing an immersive experience. But I admit this is all just a hunch.

MC: The Situationists called for a seizing of the “means of conditioning.” Should we also aim to seize the means of programming? And what connections might we draw between these two projects?

LE: As I try to imply above, contemporary computing is one of the most profound manifestations of late capitalism–I only have a superficial understanding of the Situationists but, ultimately, the only reason why our devices are now not only closed to us but gradually disappearing under the guise of ‘seamlessness’ is because, from a profit-oriented perspective, a universal homogeneity of devices is the ideal; and now, to accelerate that homogeneity, these devices must also be invisible. It does seem to me that the way out is to hack, appropriate, seize, rebuild in our own image. The only problem is that even ‘hacking’ and ‘making’ have become big business, as Make Magazine and all its spin-off projects (Maker Faire, Craft Magazine, Maker Television etc.) continue to be enormously profitable and as mega corporations such as Google and Facebook hire hackers and even hire Occupy Wall Street activists. Nonetheless, I have a tremendous amount of respect for utterly unprofitable experiments in taking control of our technology–I’ve begun working on my next project I’m calling OTHER NETWORKS which looks at networks that exist outside of or before that behemoth “the internet” came to dominate our online interactions. One project in particular, Occupy.Here, seems to fit in nicely as a Situationist-inspired seizing of the means of programming in that it is a network that exists entirely outside of the internet via a wifi router near Zuccotti Park in New York City which anyone with a smartphone or laptop can access through a portal website. In other words, it offers us a beautifully simple, elegant way out of the way the internet disempowers us through a system of distributed control.

MC: It used to be that people could take apart and reassemble the mechanical devices in their lives (toasters for example), and these devices were constructed with universal parts (screws, etc) …How can the tinkering impulse survive in the face of smart devices, blackboxing, proprietary components, etc.? (Maybe not everyone is a tinkerer, but…)

LE: I’ve wondered the same thing but projects such as Occupy.Here and devices such as Raspberry Pi (that are as inexpensive as a book) or platforms such as Arduino that are meant to help us build other devices give me hope. But also I think it’s important to remember this blackboxing is largely (but of course not only) driven by Apple and that, as I’ve come to learn, this tinkering impulse is alive and well in countries outside of the U.S. For example, I recently met a graduate student from Israel who assured me that nearly all of her friends and family members living in Israel used PCs or Linux devices and everyone regularly takes apart and fixes their machines. This was quite a revelation to me, to realize that the overwhelming push to disempower users/consumers with closed devices may be a western phenomenon.

MC: Your book suggests that an interface that is truly going to be a “friend” to the user is NOT necessarily an interface that is going to make all the fundamental decisions in advance for the user, etc. Maybe talk about how future interfaces might possibly instead more fully engage the creativity of the user (and/or invite the user to engage at a deeper level with the capabilities of computers)? Also, can such be accomplished in a way that draws in all users and not just geeks?

LE: Uncovering documentation from the 1970s on Smalltalk and on Alan Kay’s vision of a Dynabook (as a device that would have given users the ability to create their own ways to view and manipulate information) demonstrated to me that there are real alternatives to the binary of experts on one side and everyday users on the other. This is a false dichotomy, a convenient construction invented to convince people that closed devices were, as an advertisement for Apple Macintosh put it, computers “for the rest of us.” It is perfectly possible in theory for us to have interfaces in the future that are open, extensible, and configurable to the expert or novice user. The problem is, first, that there’s no way to avoid the need to institute nationwide education in programming and digital literacy in public schools as I imagine that any device built for configurability will also have to be programmable; and second, it’s hard to imagine a configurable, programmable device that will generate maximum profit – companies and western consumers would have to change in a radical way that seems unsupportable by the dictates of late capitalism.

MC: The computer’s identity as tool for efficiency seems to overshadow the computer’s poetic potential. I use ‘poetic’ here to mean “the development of absolutely new forms of behavior”–a Lettrist definition of poetics which is notably similar to Mckenzie Wark’s definition of hacking (which you cite): “creating the possibility of new things entering the world.” …Has the poet always been a sort of hacker?

LE: I think so! Seeing writing, especially innovative poetry that lives on the edges of acceptability, as studies of media has brought about a profound shift in my thinking so that I’m no longer interested in trying to seeing through letters and words to get at the representational meaning but instead I think about how the writing registers media effects. I’m not sure how far back you can go in literary history and make this work, but there’s no question in my mind that poets such as Emily Dickinson, Stéphane Mallarmé, and of course a whole host of experimental early twentieth century poets were pushing up against the limits of what the media of their time could and could not do for/with writing. And to the extent that these poets are engaged in a continuous cycling of tinkering with the limits and possibilities of writing media of their time which in turn re-enlivens our language, it does seem like poetry [defined as such] could be seen as hacking.

MC: Diane di Prima wrote: “THE ONLY WAR THAT MATTERS IS THE WAR AGAINST THE IMAGINATION / ALL OTHER WARS ARE SUBSUMED IN IT” [emphasis in the original]. Do you think we have the means to win this war (which is also, it would seem, Richard Bailey’s “war against conventionality”)? To what degree is it a question of interface?

LE: Nearly all of our tools, no matter how simple, are interfaces for accessing other sets of tools (think of hammers and pens as interfaces to access nails and paper) so that not only are nearly all our actions mediated by interfaces of some sort but also there may not be such a thing as an unmediated, interface-free interaction. So, it’s possible to say that it’s always been a question of interface–the problem now is that corporations are making it as difficult as possible to perceive these interfaces and to see how they’re mediating and even determining our experience.

To get to your question about imagination, it’s getting harder and harder to be weird, or even encounter the truly weird which, for me, is “imagination”–existing in or seeing the world askew, envisioning new kinds of existence in the world because everything is indeed mediated tightly and thoroughly for us, making it next to impossible to be anything but a consumer. In this sense, winning the war could come down to making or producing either as an end in itself or as a means to just exercise imagination.

JENIFA TAUGHT ME

CONSTANT Dullaart’s solo show Stringendo. Vanishing Mediators, Caroll/Fletcher.

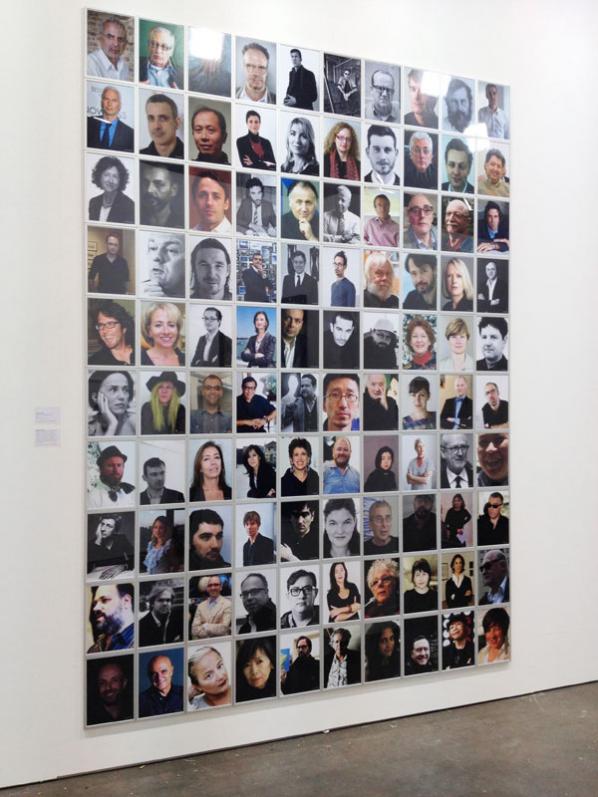

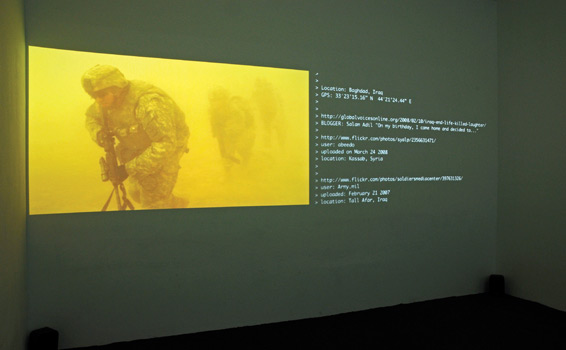

Occupying both floors of the ultimate O’Doherty white cube of Carroll/Fletcher, Dullaart’s first solo UK survey show Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators consists of 27 works – many of them newly commissioned. The works have in common Dullaart’s pervasive aspirational tactic of queering and laying bare the architecture – both physical and virtual – of our networked yet doggedly analogue broadcast lives. Retaining a sense of sepia-tinted nostalgia for the Pong era Internet, many of the works in the show pay tongue-in-cheek homage to the revolutionary and democratic aspirations placed on the web at the beginning of its popular adoption – albeit primarily by white, male middle class Americans. Throughout the exhibition, Dullaart forensically tracks, seeds and traces remnants of our digital past and places them in direct dialogue with the power relations embedded in the terms and conditions of how these technologies have remediated the way we encounter and interpret our world now. This unveiling and excavating of the digital gesture – whether personal or brand mediated – and the freezing of the smoke and mirrors affect of software semantics isolated on the plinth of the gallery. It will be familiar ground for many of us in the business of the aestheticization of our precarious position as prosumers in surveillance society. However, as Dullaart lays bare the soft terrorism of the interface and the slowly encroaching disillusion of the clunky binary “digital” and the “physical”, he points towards a new way of visualising the architecture of our messy public/private, social/political pathological states of disarray by introducing The Balcony as a newly envisaged site of resistance and broadcast.

Stepping off the street and into Constant Dullaart’s recent solo show Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators at Carroll/ Fletcher on a sweltering summer afternoon I am immediately transported into a trippy AC’d noughties Snappy Snaps.

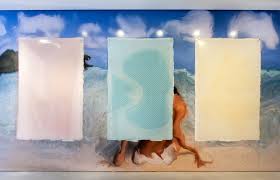

Dullaart’s signature, and now Guardian-famous, eponymous series Jennifer in Paradise acts as the hero image for the immersive world of blissfully glossy software-mediated wallpaper and slickly produced lenticular prints hanging in the entrance gallery. A Miami-hued display of software’s extensive lexicon of brushstrokes, filters and masks is flamboyantly demonstrated on the lonely yet aspirational image of a beautiful woman sitting on the beach looking out onto the tropical horizon. The promiscuous past of this image is well rehearsed; from its origins as a 1987 holiday snap – taken by co-creator of Photoshop John Knoll – to its use as crash test dummy for his ground-breaking popular software and its voracious adoption by the newly indoctrinated Photoshop masses as a subject of visual vivisection frames the staging of this exhibition. Dullaart’s archeological impulse to sniff out the rare software artefact of Jennifer points towards a general fetishization of the magic tipping point of the analogue/digital past –conjuring up a time when photography’s authenticity was still a battle to be fought. In a conversation with the artist at the appropriately ambiguous location of The Photographers Gallery shortly before his show opened, Dullaart emphasises the enduring pull of the image in his own practice. Describing the logic of the exhibition’s strategy, he sees the pasting of the Jennifer wallpaper as a “doubling” [1], or colonisation of his ongoing Jennifer experiment.

Dullaart’s Jennifer journey through the lexicon of data manipulation started when he embedded a secret stenographic message in the first re-appropriated images of Jennifer as a kind of “prize” for his growing online viral public. The first iteration(s) of Jennifer in Paradise explored the Internet’s opacity, highlighting the extent to which onscreen data is manipulated and controlled, enhanced or deformed. By celebrating and transporting the cyber-famous Jennifer into the gallery context in the form of selective editions, copies, or “abbreviations” of the digital, networked manipulation of the image, these artefacts act as both signifiers of the artists’ practice and as tempting photographic editions in their own right. A fact the artist is well aware of. However, the overarching social commentary implied in the freezing of this signifier of mass viral circulation is that the image became a coded Trojan horse for the prosumers’ 2.0 hypermarket as it was seeded, tracked mediated, remediated and mimetically distributed through the newly democratised digital commons.

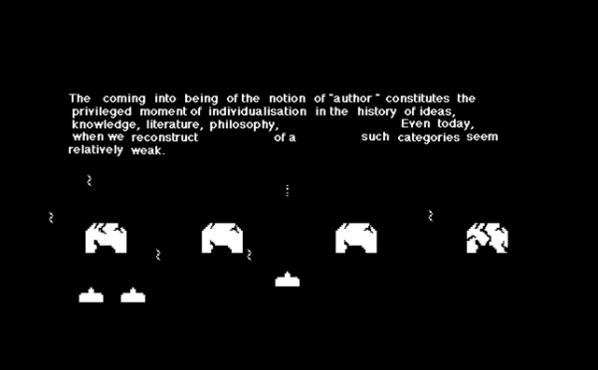

It is in this mimetic gesture of versioning – a trope embedded in the very DNA of software development – that the artist does not just reference and make visible software’s surface gestures, but actually performs software’s versioning impulse, exposing it as a form of corporate cultural imperialism and spotlighting the newly negotiated role of authorship in the process. The artist’s persistent and persuasive disruption of the role of authorship is a common and recurring obsession running through his practice – from objects, to online queering of domain names, to his performances. A personal/impersonal example of this is played out in the exhibition by a row of seemingly innocuous family photographs. The series of family pictures from the 1980s are, according to Dullaart, the cleanest example of performative authorship. The photos were simply sent to Apple co-founder Steve Wozinak for him to sign and send back to the artist – resulting in the “re-authoring” of Dullaart’s childhood memories. This simple performance of capital control and authorship of so-called private identity is mainlined into Dullaart’s practice, and speaks to the artist’s core impulse: “this is exactly what I do – I take what isn’t public and I re-posses and reprocess these artefacts and re author them into a different spectrum”. [2]

In another act of ambiguous reverie of the commercial canon of software are the three pieces entitled Bill Atkinson demonstation drawing, (no.5, 12 and 18) hanging on the other side of the gallery, positioned against the Jennifer-tiled wallpaper. These drawings from the 23 stages of the first drawing made by Macpaint creator Bill Atkinson are printed in monochromatic hues sandwiched between photopolymer plates. These meticulously restored physical gestures of one of the first drawings executed by commercial software are particularly important for the artist. He sees this attempt at drawing made in the “strong consumer software” of Macpaint as a kind of totem or signifier of the emerging lexicon of the new canon in art history.

Beautiful fetishistic rubbery objects in themselves, the physicality of these works demonstrates the materially-dependent, performative intent in Dullaart’s practice. As these monochromatic objects react and change to UV light – hardening and cracking – any collector of his work needs to embrace the precarious temporality of the objects themselves. This is true of all of his work – including domain names, websites, his own online identity etc. and Dullaart emphasises that the conscious situating and staging of his works in the framework of time is one of the most vital components of his practice.

This animated relationship to instability and time- dependency is clearly demonstared in his player paino piece Feedback with Midi Piano Player at the heart of the exhibition. An algorithm interpreting polymorphic songs is played out through the grand piano in the gallery in an apparent circus-like celebration of the computer’s magical powers. However,as the recital unfolds, it is full of little mistakes – the songs are too complex for the computer to relay in a coherent feedback loop. For Dullaart, the inaccuracy and amateur quality of the computer/piano recital delivers a quasi -human quality of cuteness – an increasingly desirable quality in our popular technology, and an indication of the drive towards the synthetic anthropomorphism of digital objects and structures in general. This inevitably recalls Marx’s highly questionable use of anthropomorphizing comparisons of the commodity to children and women to underscore the “fetish character” [3] of commodities – the phantasmatic displacement of the sociality of human labour onto its products, as they appear to confront each other as if operating independent social lives of their own. In this sense, the “cuteness” in Dullaart’s piece might be seen as an intensification of commodity fetishism’s logic redoubled (like Jennifer) – as the viewer is connected to the unavoidable fantasy of fetishism, itself already an effort to find an imaginary solution to the irresolvable “contradiction between phenomenon and fungibility” [4] in the commodity form.

However, if this “cuteness” maintains fetishism’s overarching illusion of the object’s animate qualities – in this case the clumsy performance- at the same time it wants to deny what, in Marxian terms, these animated commodities articulate as “Our use-value may interest men, but is no part of us as objects…We relate to each other merely as exchange values.” [5]

Dullaart then shifts his attention to the main focus of the exhibition – the conscious construction and showcasing of his proposition of a new way of entering into a contract with our networked, hyper-published -selves: the balcony. The two physical balconies presented in Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators (one of which is accompanied by a digital ticker-tape text of his Balconism manifesto) are both visual prompts and, in a sense, demos, of Dullaart’s concept of balconisation. In direct acknowledgment of the hyper- mediated image of Julian Assange standing on the balcony of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London – Dullaart starkly illustrates this liminal, politically charged space where we bear witness to a clear slippage between UK and Ecuadorian territory. To Dullaart, the balcony represents a ‘space outside society’ [6], and this new space of public address marks a shift in responsibility in self-broadcast/publication in the digital commons and the social media sphere. According to Dullaart, we all need to recognise our position on the balcony in our hybrid public/private pathology and modus operandi of quasi-addictive self-broadcast.

On the balcony we should be ready to escape the warm enclosure of the social web, to address people outside our algorithm bubble. In the context of the show, the balcony is positioned as a higher order theory for how we should respond to the process of digitalisation as a whole, to how corporations and programmes structure our understanding of the world. We need to stand on our particular balcony ‘and choose to be out in public and we have to define cultural codes of how to do that’. [7]

What Dullaart’s exhibition Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators offers anew is an alternative proposition of spatial code through which to understand our steadily (re) negotiated locations of private and public space and the possibility of somewhere inbetween from which to enact a certain kind of everyday De Certeauian [8] tactic – the Balcony.

Dullaart’s solo exhibition ended at Carroll / Fletcher on 19th July 2014.

Featured image: still from Fatima Al Qadiri / Sophia Al Maria HOW CAN I RESIST U

E-Vapor-8 is a very cool group show which looks and feels about as much like a club as you would want it to. It features a series of haunted works opening onto the “death of rave” — and what that death means, when it happened, and if it is still happening, are the most interesting questions provoked by a visit.

Works by Fatima Al Qadiri, Daniel Swan, Petra Cortright, Rhys Coren become the characters and rooms of a labrinthine underground culture which takes emotion, history, sexuality and race as its headliners and resident evil. It is a small exhibition, considering this scope, and perhaps not the show which the curators would lead us to believe.

The notion of cultural ‘Afterlife’ enters the fray as surely and convincingly as a sweaty-metallic-render 3D blade drifting though green wireframe. Afterlife is a ziegist topic – Transmediale’s Afterglow theme explored an afterward of an already exploded digital scene; Mark Fisher’s term ‘Hauntology’ connected Derridian theory to underround music/artists like Al Qadiri and Maria Minerva; and the recent New Death exhibition at FACT featured works such as Jon Rafman’s installation, depicting an indecent internet-accelerated-libido as a kind of end-of-the-world-is-now scenario. In these works and perspectives the realm of the afterlife is shown to be a nuanced one from which to view the epochal changes culture has undergone, and this is why a show like E-Vapour-8 feels so timely.

The name of the exhibition is taken from a 1992 rave track, but it also makes me think of the recent rash of e-cigarette shops…

and, more portentiously musical genre coinage I know from reading Adam Harper’s contemporary music commentary: vapourwave –

“At the end of the world there will only be liquid advertisement and gaseous desire. Sublimated from our bodies, our untethered senses will endlessly ride escalators through pristine artificial environments, more and less than human, drugged-up and drugged down, catalysed, consuming and consumed by a relentlessly rich economy of sensory information, valued by the pixel.” Adam Harper in DUMMY

Several of the best works here are available to view online, and benefit greatly from the throb and thurst of this gallery setting. Watching Daniel Swan’s Plane Drift V on a hi-def monitor, I appreciated the use of lo-fi pixilation as part of the affective ether of the work, as the utopian 3D crumbles into a flat and luscious digital irony. The video ends its loop on a frieze of a 3D plaque stating ‘Return’, evoking the role of the loop in dance culture, and the mode of reinvention in evidence throughout the show.

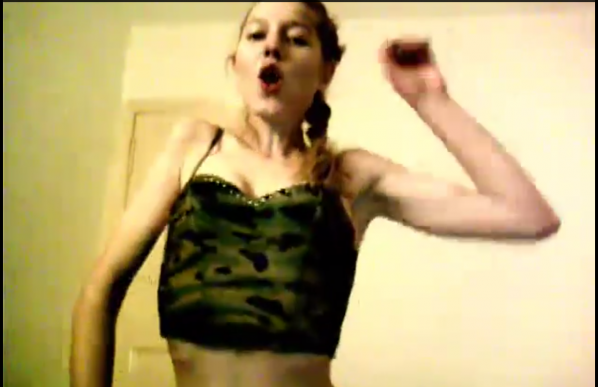

Fatima Al Qadiri’s tune How Can I Resist U with a new video by Sophia Al-Maria dominates the main gallery space with its unsettling deep bass underflows, and audaciously cool bringing together of urban architecture with international dance cultures. In the other room, Petra Cortright’s voyeuristic film Lara Practice shows a young girl trying out her ecstatic dance moves presumably to rewatch later – a tragic pantomiming of ‘happy hardcore’.

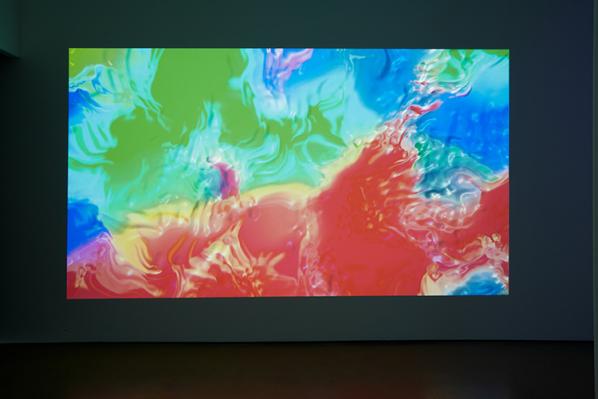

Other works play on the aesthetics of given rave cultures. Travis Smalley’s Wave Trancendence splays the multi-coloured trippy aesthetic of early hardcore flyers as a sickly overlush chill-out visual.

Adham Faramawy’s Lifeproof iPhone Cover revisits the metallic Photoshop filter and puts it in motion, his work simultaneously harking back to late-90s era Drum n’ Bass, while having the look and feel of a vapourwave.jpg – except instead of vapour-wave’s marble, the plinths and stands for Faramawy’s work ooze black foam, like an ashtray left in the alley behind your mum and dad’s for thirty years.

This incongruous collection of perspectives, along with the jostling beats across the whole show provoke a kind of nervy excitement. Installations in the show also play and elide bliss and paranoia. Harry Burden inverse-casts a crumpled car wing and paints it in a pearlised blue and green like a strange beetle.

Alexandra Gorczynski’s liquid dream-like video peers up queasily from under a glittery canvas bedcover, and Maria Olsen’s gold tapes in a heap on the floor; each item together and the same, but the artifacts themselves – the music, the person – alone in their capsule.

Only Rhys Coren’s playful video-loop doodles set across three screens to a chirpy four-four house beat seem unequivocally ‘happy’ – but we notice that even here, the screens face away from each other, and the animations jiggle on their own buzz.

Sitting off in the corridor like a rushed-out raver afterwards, the trouble with this show sinks in. In her short introductory essay, curator Francesca Gavin acknowledges that many of the young artists she features are not old enough to have experienced the first ‘white glove’ rave referenced in the title of the show, but neglects to acknowledge the life of rave and dance culture which these ‘subsequent’ generations find ourselves mourning. To an extent, the use of Acid House here has more to do with marketability than criticality – but to jump right from early 90s rave to the work of an artist like Harry Burden, Adham Faramawy or Fatima Al Qadiri, and to locate the older Jeremy Deller’s smiley-face poster artwork at the ‘fulcrum’ of this show, is to willfully ignore the racial and social complex of the Drum’n’Bass, Techno and Trance which followed (as documented most memorably by Simon Reynolds in his Hardcore Continuum series for The Wire).

Gavin’s insistance that the exhibition ‘examines the utopian ideas surrounding rave before its failure’, seems to ignore what the artists in the show might consider the actual moment of rave’s failure. This central oversight leads to others. The choice of JG Ballard’s Crash as key-text, while obliquely relevant as an aesthetic touchstone of dystopia, doesn’t really reflect on the ‘realness’ of the scene artworks such as Gorczynski’s reference – it would be nice to have a chance to review the impact of a novel like Irvine Welsh’s Maribou Stalk Nightmares on this generation, or reflect on how current novelists such as Tao Lin use prose style to echo the afterlife of re-illusioned rave and drug culture.

The best works in E-Vapour-8 exist as echoes a UK club culture with more ambiguous relations to capitalism and politics than the radical and resistant Acid House rave. The void left by the hedonistic lifestyle is a simulacrum in a work like Faramawy’s, for the void left in our lives by the death of the hope of capitalism, and our continued afterlife within it – like a club we’re forced to keep revisiting even though it’s too expensive the DJs are shit and people keep getting shot.

The deep cuts in Sophia Al Maria’s and Fatima Al Qadiri’s How Can I Resist U are reconstituted and assimilated into an elegy – to the ‘bootyshake’ and bass, but also to social distribution and emptying out of utopian modernist architectures, using the lo-fi and hi-rise as distinctly modern hallucinations, and touching clearly on Sheffield’s own rave heritage in buildings such as the Park Hill flats.

Seen in the light of her generational ‘shortfall’ (being too young to have been seen Altern8 in the Hacienda, but old enough to have got down to Ed Rush at The End) Petra Cortright’s subtle and lyrical cutting and smeering of an original video and its soundtrack in Lara Practice, reminds me of the millenial dancefloor vibe – how out of place those moves were, how re-territorialised they immediately became.

“I start to wonder if she, like me, got sucked in by Ardkore’s explosive euphoria, its manic, fiery-eyed glee, and then got carried along by the music’s logical evolution to wind up at another place altogether, dystopian rather than utopian.” Simon Reynolds ‘”Slipping Into Darkness” The Wire #148

As examples of the thematic depth offered in this show, the Al-Qadiri/Al-Maria and Cortright videos capture the implosion of a naïve energy. By focusing on the female body in the throes of bass, they present distinct and equally valid breakages taking place between anticipation and experience – and the emergence into a darker real and global hyper-real. The artists’ contemporaries in the music scene (including vapourwave artists such as Vektroid and Oneohtrix Point Never) deserve some credit for informing a culture which can act in this way.

It would seem that a gallery of this stature, and a curator with the contemporary culture credentials of Francesca Gavin – visual arts editor at Dazed – would be more keen to link visual art with actual dance culture, rather than a fully assimilated cultural caricature like happy hardcore… but then, the exhibition itself is an opportunity for us to do just that.

I recommend a visit – the show is on until August 17th. Those who were in a circa-1998 nightclub will recognize the nervy and unsettling sensation of the corridor or cloakroom queue, the combination of E-high with screw-face attitude. A steady, percolating dark bass among the hallucinatory imagery and tongue-in-cheek synth refrains. Those who weren’t will undoubtedly find their own touchstones in these independently deeply poignant and distinctly contemporary works.

Play with the Rubik Cube simulator online! Drag the pieces with your mouse to unjumble the puzzle.

Featured image: Image from “Otherworldly” at Manchester Urban Screens 2007. Curated by Michelle Kasprzak

Eva Kekou interviews Michelle Kasprzak, a Canadian curator and writer based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She is a Curator at V2_ Institute for the Unstable Media and the Dutch Electronic Art Festival (DEAF). She has appeared in Wired UK, on radio and TV broadcasts by the BBC and CBC, and lectured at PICNIC. In 2006 she founded Curating.info, the web’s leading resource for curators. She has written critical essays for C Magazine, Volume, Spacing, Mute, and many other media outlets. She is a member of IKT (International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art). Michelle is also an avid weightlifter with current personal records of 80 kg squat, 52.5 kg bench press, and 90 kg deadlift.

Eva Kekou: Can you give us some info about your work as an artist and curator and specifically your work at V2_?

Michelle Kasprzak: I was trained as an artist, but my art career feels many moons ago now. My first love was photography, and I spent many hours in the darkroom as a teenager. Later on I moved into live video mixing for performance contexts and parties, single channel video works, and integrating technologies like speech recognition and found objects into performance.

I was also curating throughout this time, though for many years it took a back seat to my artistic practice. Eventually I realized that I was more interested in curating and writing than making the artworks myself. Of course, one should never say never, so I may return to art making someday, but from that point onward and until the present time I focused full-time on curating and writing.

This was the mid 2000s and it was a pretty exciting time to be a media arts curator. It felt as though things were gaining traction. So many years after Cybernetic Serendipity had laid the foundations, we had exhibitions such as The Art Formerly Known As New Media curated by Sarah Cook and Steve Dietz to stimulate the dialogue about new media art and how to exhibit it, and take it all to the next level.

Fast forward to now: a few years later, I’m a curator at V2_ Institute for the Unstable Media in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. V2_ loomed large for me as a young undergraduate in Toronto studying new media – it was this far away place in a city I didn’t know with this massive reputation for doing edgy, interesting things. I wouldn’t in my wildest dreams at the time ever imagine I would one day work there.

As an institute, V2_ has been through a number of key transformations and I think it’s interesting to map that on to what was happening at the time both in art and in society. It started in the 1981 as a squat (which was common in the Netherlands at that time) and the founders called it a “multimedia centre”. Sonic Youth, Laibach, and Einsturzende Neubauten played there. The “Manifesto for the Unstable Media” was written in 1987 and arose out of a dissatisfaction with the status quo and it said things like “Our goal is to strive for constant change”. Following the Manifesto, a series of “Manifestations of the Unstable Media” were created, which evolved into the Dutch Electronic Art Festival (DEAF), a festival which continues today. In 1994 V2_ moved from s-Hertogenbosch to Rotterdam and has remained there ever since.

Around that same period of the mid- to late-90s, the growth of internet access and support for artists working with networked technologies caused V2_ to change its focus in this direction. In 1997, V2_Lab opened as a hub within V2_ to initiate and support the production of artistic projects investigating contemporary issues in art, science, technology, and society.

EK: So today, in this age of ubiquitous technology and information, where does an institute like V2_ find its place?

MK: I see media art as a category splintering and dissolving, with bits of its ethos absorbed into design, contemporary art, craft, and hacker culture – and vice versa. One way to find a place in the world is to stay true to the origins of V2_ in terms of its squatter ethic. So for example, we (myself and my colleagues, particularly Boris Debackere and Michel van Dartel) recently rewrote the mission statement of the Lab, declaring it “…an autonomous zone where experiments and collaborations can take place outside of the constraints of innovation agendas or economic and political imperatives.” Which is not to say that anything goes, but states explicitly that we’re especially open to people looking for a home for a risky or unconventional idea. Also, following on from several years where V2_Lab hosted residents based on three fairly technologically-driven themes (wearables, augmented reality, and ecology), the Lab has taken on a new direction of being methodologically-driven, and looking at themes like re-enactments, design fiction, and extreme scenarios.

I think it’s a key shift, because in order to “strive for constant change” as we said in the original manifesto, linking to any one technology of the moment seems too static and limiting, as well as reducing our reach into areas with interesting and relevant artistic research occurring, but which might not have much technology involved in an apparent way. The fact is just about everything being made right now is a product of the technological age we live in, so it’s more useful to think in terms of methods and approaches rather than whether something fits a classic definition of what media art is or not.

Take for example one of our latest commissions, Paper Moon by Ilona Gaynor in collaboration with Craig Sinnamon. Ilona and Craig were at V2_ for a few months at the end of 2013 and both have design backgrounds. The work, to describe it in a formal sense, is a series of objects and paper-based work arranged in a specific fashion along with a short screen-based animation. This seems a little different than what one might expect to see at V2_, except for small clues in the creation of some of the items (the animation is generated with 3D animation software, some of the objects have been 3D printed). But more significantly, in its thematic Paper Moon enters the realm of the unstable by exploring the emerging legal definitions and loopholes of outer space – particularly the treatment of the moon and other celestial bodies. Our legal system on Earth, as Ilona put it “…has no definition for what ‘Outer Space’ actually means, what it is, and where it is. The problem we face with such literal unmarked territory is the emergent field of ‘Space Law’ becomes genuinely speculative.”

Ilona’s residency was part of V2_Lab research project Habbakuk, about Innovation in Extreme Scenarios. The Innovation in Extreme Scenarios research thread was generated in reaction to the introduction of an innovation agenda for the arts as part of the Dutch government’s ambitionto be “one of the world’s top five knowledge economies” by 2020. As a way of directly addressing this policy direction, V2_Lab began undertaking research into the nature of and appropriate contexts for innovation through a series of expert meetings, workshops, site visits and interviews over the course of 2013-14. The final outputs of the project, which will comprise project commissions and a final publication, will be used as a tool to engage with the policy conversation on innovation in a more profound way. So we’ve been doing work on this at home and abroad, holding expert meetings and interviews in the Netherlands, Canada, Hungary, and Denmark.

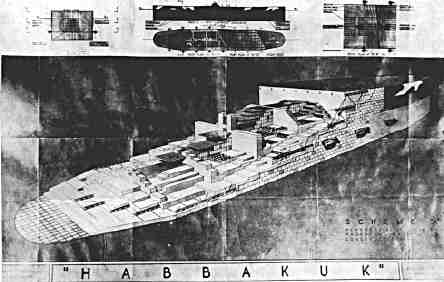

The Dutch policy context explains the “innovation” part, but the “extreme scenarios” part came from somewhere else. For that I was inspired by the World War II story of the Habbakuk aircraft carrier which was commissioned by Winston Churchill. The Allies were plagued by German U-boats, and Churchill desperately needed an innovative solution to this particular problem. In the extreme scenario of war, Churchill authorized the production of a radically innovative solution: building an aircraft carrier made of ice – specifically Pykrete, a frozen mixture of water and sawdust.

Pykrete seems like ordinary ice but the addition of sawdust makes it into a kind of wonder material that takes longer to melt and invulnerable to bullets. In the end the massive ship, which was to be christened “Habbakuk”, never saw the theatre of war but considerable effort was put into developing a prototype in total secrecy deep in the Canadian Rockies.

Inspired by both the Habbakuk story and our own policy situation brewing at home, some of the questions we’ve been trying to answer with this research are things like: What are the best contexts for innovation to take place? What are the myths surrounding how innovation occurs? Does the pressure of an extreme scenario inspire innovative solutions, or only eccentric, unrealisable concepts? What’s the U-boat problem of today?

The theme of Innovation in Extreme Scenarios is also being explored in the programme that I devised and curate at V2_ called Blowup. Blowup refers to a number of things: the way that you can blow up a photograph, a balloon, a situation, and of course – the Antonioni film. I see it as a container that presents things in a slightly different way each time, and that its main remit is to examine the things that are changing the way we live now, or reinforcing the status quo of today. The formats for Blowup have varied a lot: from a workshop, to a talk show, to a talk show within a talk show, to a five day booksprint, to an exhibition in a pop-up space. The topics have been equally eclectic: art for animals, outer space, journalism as an art practice, object-oriented ontology, and so on. The most consistent element is that each event has an eBook released along with it, and that these eBooks explore the topic in a little more depth, but also combine previously released material with newly commissioned material. We all have bulging bookshelves and intend to always read something later – by bringing relevant old texts back into the forefront, I hope to give them a chance for a second look (or a first look if you missed it when it was released).

EK: What are your hopes and dreams for the future?

MK: For the future, I think new ideas are incredibly rare, and that doesn’t bother me at all – what interests me is that dreams that were previously impossible are becoming possible, and so my passion continues to be seeking out the inventive eccentrics with grand master plans, and being a part of realising that. Churchill dreamed of ending the war with a boat made of ice more than ten times the size of the Queen Mary. These are the kinds of big wild dreams – in scale and in scope, if not in my discipline – that I dream of.

Die GstettenSaga: The Rise of Echsenfriedl review. SPOILER WARNING!

Johannes Grenzfurthner’s Post-Apocalyptic DIY Epic on Makers, Hacktivism and Media Culture.

“A mad post-collapse satire of information culture and tech fetishism, in a weird sort of melding of Stalker, Network, and The Bed-Sitting Room.” (Richard Kadrey)

Die GstettenSaga: The Rise of Echsenfriedl is an Austrian hackploitation art house film by Johannes Grenzfurthner, mastermind of the international art-technology-philosophy group monochrom, co-produced by the media collective Traum & Wahnsinn. Reimagining the makerspace as grindhouse, the story is set in the post-apocalyptic aftermath of the “Google Wars” – an armed global conflict between the last two remaining superpowers China and Google – which has turned what remained of the Alps into a Gstetten.

In Austrian German, “Gstetten” translates to wasteland, outback or ‘fourth world’ (Manuel Castells) and is a popular name for provincial towns – and sometimes just the less sophisticated parts of them. The area’s biggest semi-urban sprawl is Mega City Schwechat, the former home of Vienna International Airport, a refinery and a beer brewery. It is governed by the evil media mogul Thurnher von Pjölk (Martin Auer), a pretender who claims to be the inventor of key publishing technologies such as letterpress printing and rules the area with his tabloid newspaper. But the hegemony of his yellow press empire is contested by – spoiler alert! – makers, hackers and nerds, who are more leaning towards electronic media such as the recently rediscovered television. In order to get rid off this bothersome opposition, Pjölk devises an evil plan for wiping out Schwechat’s insubordinate creative class.

In an insidious political move, he pretends to reach out for the technophile faction by commissioning two of his reporters, the bootlicking opportunist Fratt Aigner (Lukas Tagwerker) and the brainy geek girl Alalia Grundschober (Sophia Grabner), to conduct an exclusive TV interview with the ultimate Gstetterati icon, the legendary innovator Echsenfriedl (“Lizard Freddy”) – on the basis of precarious employment conditions. The title character, who turns out to be an basilisk, embodies a mix of Steve Jobs, Richard Stallman and Julian Assange and lives in the depths of Niederpröll in his hideout much like Subcomandante Marcos – partly in order to protect the world from his killing gaze, which would, audio-visually transmitted, turn the whole of his fan base immediately to stone.

Grenzfurthner’s sci-fi-horror adaption of the Divine Comedy takes us on a retro-futuristic post-cyberpunk adventure in the tradition of cinema grotesque back to the dark days which preceded the Internet. The journey of our heroes – distinctively resembling Tarkovsky’s ‘stalkers’ – is a quest for extinct media technologies but their search for Echsenfriedl eventually leads the two protagonists to a deepened understanding of who they really are: the media industry’s precarious workforce under spectacular capitalism. While Fratt’s dirt track to enlightenment is paved with stumbling blocks, his brainy Beatrice advances with the determination of a Harawayian cyborg who makes use of her superior technical skills to save them from the zombified folk populating the Gstetten: uncanny creatures from the Kafkaesque bestiarium of Austria’s undead bureaucracy and its hanger-ons like armed-to-the-teeth Postal Service subcontractors (brilliant: monochrom’s Evelyn Fürlinger, also Grenzfurthner’s ex-wife) or the once powerful Farmers Association led by Jeff Ricketts (Firefly, Buffy the Vampire Slayer), who are worshipping antique pre-war EU funding applications as their sacred scriptures. Our friends receive the final hints for their search from the Sphinx Philine-Codec Comtesse de Cybersdorf (Eva-Christina Binder), a fantasy femme fatale who is torn between Plöjlk and Echsenfriedl, and the bearded drag queen Heinz Rand of Raiká (David Dempsey), an eccentric agricultural cooperative banker and possible descendant of Conchita Wurst.

The Gstettensaga’s fascinating cinematic pastiche is more than just a firework of rhizomatic intertextuality, a symptom of the depthlessness of postmodern aesthetics or excessive enthusiasm for experimentation in the field of form. In their infamous 1972 book Anti-Oedipus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari have identified the technique of bricolage as the characteristic mode of production under “schizophrenic” capitalism, a facet triumphantly magnified by the filmmakers. If every discourse is bricoleur, like Jacques Derrida suggested, suddenly ‘context’ can become the artist’s material or even a form of art in its own right:

“The more artists are consigned to an existence within a patchwork of niches, the more dependent they become on information resources, communication and networking. In this respect, aesthetic artefacts must take a stance toward a plethora or markedly heterogeneous contexts that sediment in one way or another: the conditions and circumstances surrounding their production, their various social fields from which (and for or against which) they speak: real or imagined audiences toward (or against) whose values a work, an approach or a position is targeted. This play with the factors affecting it and among which it must mediate has become an essential trait on an art form that might best be described as ‘Contextualism’.” [1]

What I found especially intriguing about the Gstettensaga is how the filmmakers responded to the various challenges of the feature film format by contextualising the whole production process, distribution, language adaptions (subtitles are an integral part of the story), soundtrack and even the viewing experience.

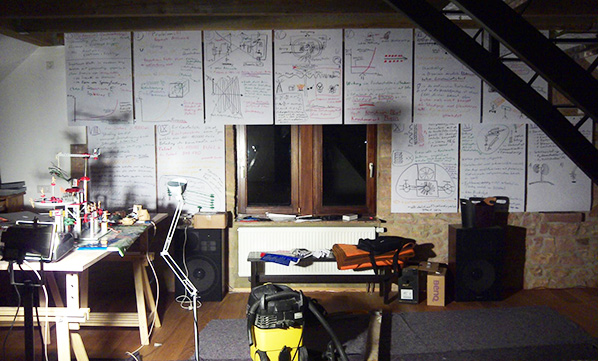

The film was initially commissioned by Austrian public broadcasting station ORF III as part of the series Artist-in-Residence for a budget of only €5000, set to be produced within a six months period. In response, monochrom used an embedded prank to raise money. The movie contains a text insert similar to watermarks used in festival viewing copies, which asks the viewer to report the film as copyright infringement by calling a premium-rate phone number (1.09 EUR/minute) and enabled Grenzfurthner to co-finance the film with proceeds from this new strategy he has named ‘crowdratting’. [2]

The Contextualist script – including outlines of scenes for improvisation – was written by Grenzfurthner and Roland Gratzer in just a couple of days in November 2013 in a Viennese restaurant. They also incorporated ideas that came up during their weekly meeting with the entire production crew, whereas some of the backstory was first created for monochrom’s pen-and-paper role-playing theatre performance Campaign. Principal photography – the camera work of Thomas Weilguny deserves the highest praise – commenced on December 2, 2013 and ended January 19, 2014, which left nearly 5 weeks for post-production and editing. Due to the fast production process and the financial limitations, no film score was composed for the Gstettensaga – instead, Grenzfurthner used an assortment of 8bit, synth pop and electronica tracks especially for their specific retro quality because “they may sound old-school to us, but not in the world of the Gstettensaga, where all retro electronic music is still impossible and futuristic.” [3]

The retro-futuristic world of Echsenfriedl is coming to a film festival, hacker con or Pirate Bay near you.

http://www.monochrom.at/gstettensaga/

Tamtam (Seara de proiectie la TT) / May 7, 2014 (Timisoara, Romania)

KOMM.ST Festival / May 11, 2014 (Anger, Austria)

Supermarkt (Dismalware) / June 7, 2014 (Berlin, Germany)

Fusion Festival / June 25-29, 2014 (Lärz Airfield, Mecklenburg, Germany)

Roswell International Sci Fi Film Festival / June 26-29, 2014 (Roswell, NM, USA)

iRRland movie night / June 30, 2014 (Munich, Germany)

qujochö Film Summer / July 3, 2014 (Linz, Austria)

HOPE X / July 18-20, 2014 (New York, New York, USA)

Fright Night Film Fest / August 1-3, 2014 (Louisville, KY, USA)

Gen Con Indy Film Festival 2014 / August 14-17, 2014 (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA)

San Francisco Global Movie Fest / August 15-17, 2014 (San Jose, CA, USA)

Rostfest / August 21-24, 2014 (Eisenerz, Austria)

Noisebridge / August 29, 2014 (San Francisco, USA)

/slash Filmfestival / September 18-28, 2014 (Vienna, Austria)

Simultan Fest / October 6-11, 2014 (Timisoara, Romania)

Phuture Fest / October 11, 2014 (Denver, Colorado, USA)

prol.kino / October 14, 2014 (Graz, Austria)

Featured image: A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter” (2009) Caleb Larsen

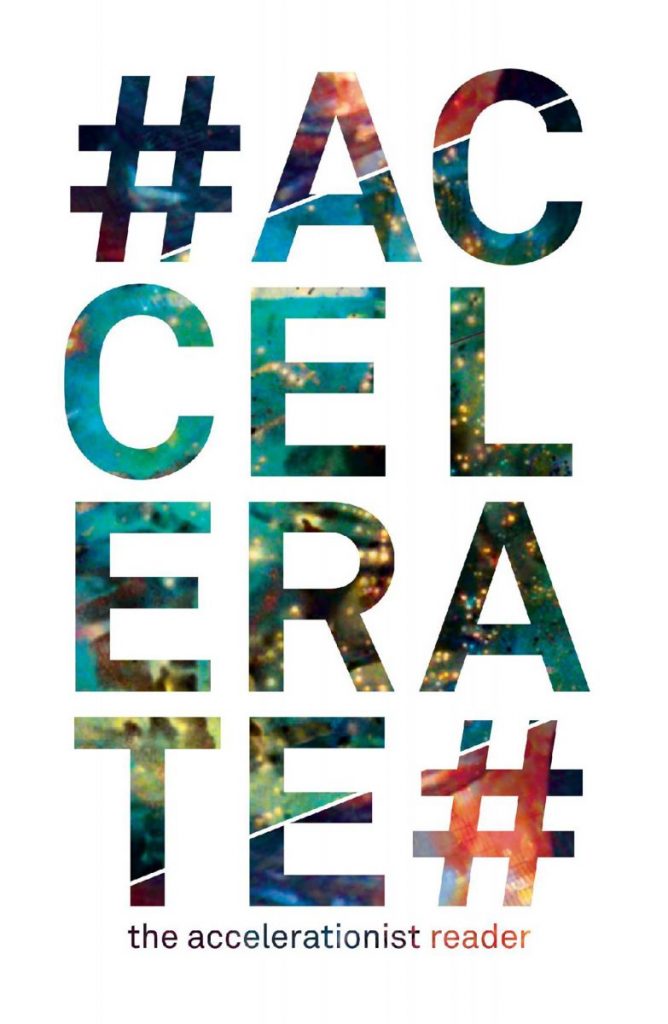

Accelerationism came to prominence in 2013 with Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’s hashtag-titled manifesto. A cloud computing-era spin on the old Marxist argument that we first need to perfect capitalism in order to transcend it, its lineage is fleshed out in a new book from Urbanomic. Urbanomic claim (among others) Nick Land’s skynet midwifery, J.G. Ballard’s science fictionalization of culture, and Marx himself as precursors to Accelerationism, establishing it as a serious anti-humanistic response to the challenges that humanity faces if it is to avoid extinction. Similar to Christine Harold’s strategy of “intensification“, Accelerationism calls for us to appropriate the value of capital’s developments and transform them materially into something else rather than attempt to resist them head-on or refuse them in our hearts.

Bitcoin is an example of an accelerationist technology. It uses Internet-scale computing resources to rebuild social bonds by destroying the requirement for them in monetary exchange. You don’t have to know me or trust me or any third parties to receive money from me in the form of Bitcoins. You just have to trust the algorithms that very publicly operate the Bitcoin network. The new Ethereum project takes the blockchain technology behind Bitcoin and generalizes to contracts for purposes other than just the transfer of money, although of course those contracts can involve payments. Ethereum contracts exist as a distributed database of small programs and their state that resembles nothing so much as an economic LambdaMOO. There’s a good guide to their promise and potential pitfalls in the talk “Ethereum: Freenet or Skynet ?” by Berkman Center Fellow Primavera Di Filippi.

Smart contracts and smart property, which uses smart contracts to identify and control ownership of physical resources, were first described by Nick Szabo in the 1990s. Smart contracts are “smart” because they are implemented as computer code rather than as legal documents. Real world examples include vending machines, in which a contract to purchase goods is encoded into the simple software that dispenses carbonated drinks when you insert the correct money, Boris Bikes, RFID card payments for photocopies, and car hire schemes that unlock vehicles and track their use with QR codes. Would-be rentiers who try to launder their ambitions with the warm fuzziness of “sharing” are salivating at the prospect, as are the incorrigible snake oil merchants of DRM, but that is not what concerns us here.

Smart contracts and smart property for art already exist. The artwork “A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter” constantly re-sells itself on eBay. The GIF ownership service “Monegraph” uses the NameCoin system to track notional ownership of instances of infinitely reproducible digital art. These are extensions of pre-digital art contracts such as certificates of authenticity or ownership for conceptual and immaterial artworks. They show a way for art to continue producing a useful critique of property and social relations under technoculture, and for new technology to feed art’s ongoing critique of its own production and nature. I wrote about this in “Artworld Ethereum – Identity, Ownership and Authenticity“, which provides code examples demonstrating how simple it is to implement some of these examples with technology dedicated to smart contracts.

Like Bitcoin, smart contracts and smart property do not require social trust to build social value, just running code. They have very limited functionality, being unable to check RSS feeds on the Internet for information for example as that information might be tampered with. This raises the question of how individuals can be encouraged to provide valid real-world information to smart contracts rather than just entering the values that will immediately profit them the most. Capitalist economics answers this with the concept of incentives. Value, and values, can be determined by the behaviour of individuals in markets in response to economic incentives. And smart contracts are intended to make markets more efficient.

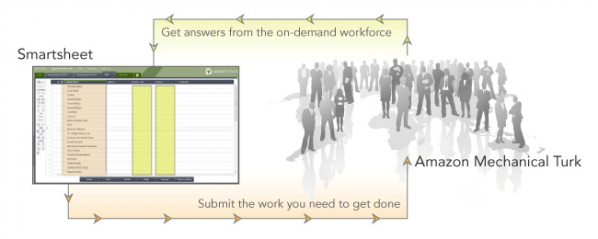

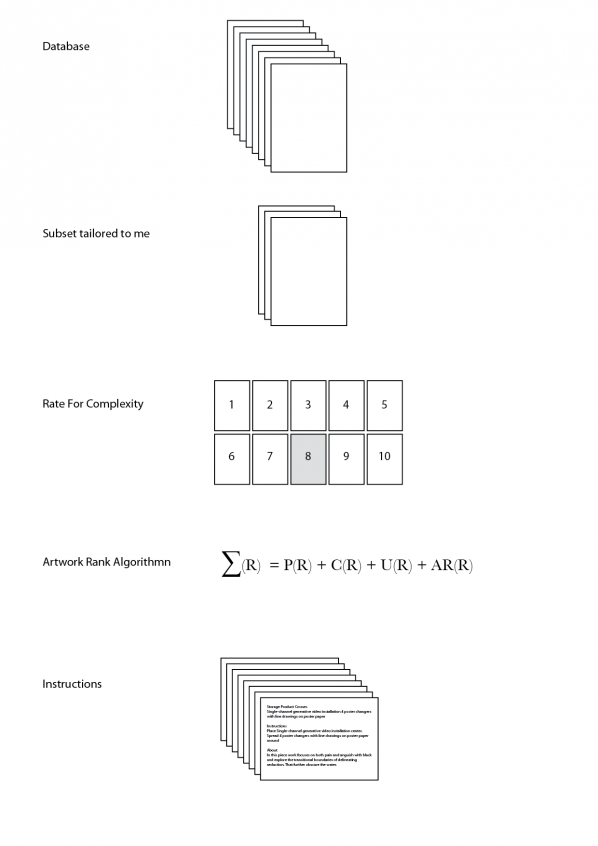

I would like to apply this agoric approach to truth to the crisis of art criticism in the face of aggregation that I identified in “The Proletarianization Of Art Criticism“. Individuals can be motivated to publish defensible aesthetic and art critical opinion in novel ways via smart contracts. I am not proposing an automated or purely algorithmic art criticism here: human activity is the core of this approach. Nor am I proposing an Amazon Mechanical Turk-style exploitation of affective labour. Rather I am proposing an Accelerationist approach, using the technology of digital capitalism to rebuild the social flows that it has destroyed.

Art is no stranger to the idea of markets, the artworld consists of one of the least regulated and therefore in theory one of the purest markets. But even ignoring the opacity and corruption of the art market, there is a problem with taking a direct approach to the art market as an arbiter of artistic value. As David Galenson‘s 2008 study of aesthetic value and market price showed there is a problem in using pure market mechanisms to establish the value of art: many “great works” have either never been auctioned or have not been to market in decades or even centuries.

I therefore propose three different approaches to art criticism via smart contracts. For work exposed to the market, the mechanisms used to price shares and other financial assets can be used. For work with less exposure, SchellingCoins and prediction markets can work alongside these mechanisms via proxies.

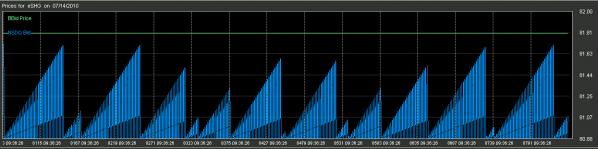

The prices of financial assets, stocks and shares or contracts for commodities for example, are set using a system of derivatives. Financial derivatives gained a bad reputation following their role in the global financial crash of 2008. By 2011 the notional value of the derivatives being traded was almost ten times the total GDP of planet Earth. And their automation by algorithmic high frequency trading is being increasingly scrutinized by regulators.

There are many different kinds of derivatives: short and long options, futures and exotics for example. But in theory at least their function is simple and beneficial. They enable individuals to profit by expressing whether they think a financial asset is over- or under-priced. This incentivizes them to act on this information. The resulting sharing of information and correction of prices benefits society.

Non-physical ownership, sponsorship, crowdfunding, dedications and more exotic value relationships to physical works and, crucially, to works that have not or will not be sold and to unownable digital art can be represented by smart contracts. These can then be treated as the underlying assets of derivatives, also represented as smart contracts, in whole or again crucially in fractional parts or shares. Buying and selling derivatives of shares in digital artworks, and particularly going short or long on them, represents a critical position on their worth. Where the underlying asset does not represent actual ownership of the artwork, we are closer to a prediction market than a financial market. But if the assets themselves attract prestige or value regardless of their proxy status they may become art objects in themselves.

Art criticism in such a market is a matter of financial investment and returns. Critics express their opinion of art, artists and artistic trends by buying and selling different kinds of derivatives at different times. If they are shown to be correct over time, the market will reward them. Derivatives are a prime candidate for implementation as smart contracts, there is already a project to create a standard language of (non-aesthetic) derivative smart contracts.

Since Ethereum contracts have no direct access to the outside world (or the Web), contracts that require information about the outside world must access it through intermediaries. This means that contracts must trust those intermediaries, and if it is more profitable for them to lie to the contracts that creates a problem. To remove this requirement of trust we can use a system that rewards people for independently supplying information that accurately reflects the true (or most likely) state of the world.

A SchellingCoin is an Ethereum contract that allows people to send it messages registering their opinion about (for example) the current temperature in Berlin or exchange rate between dollars and yen. Those that set the majority view are rewarded for doing so, similarly to the operation of a prediction market. But how do they know which value to choose? The game theory concept of a focal point, or Schelling point, is an answer to a question that people who cannot communicate will give independently because it seems natural, appropriate or special. SchellingCoins reward people who give the consensus answer to a question, and people can determine the right answer by converging on a Schelling point. For real world phenomena, such as temperature or exchange rates, the Schelling point is likely to be the correct answer. SchellingCoins can be implemented as smart contracts, removing the need for a trusted entity to run them.

Schellingcoins are designed to address external, quantitative phenomena. Opinions regarding cultural works are personal and qualitative, and spontaneous reactions to cultural works are even more so. This is different from the commonly expressed quantitative values that the SchellingCoin proposal requires. To adapt SchellingCoins to cultural criticism we must adopt the methods of collective intelligence and the digital humanities and use some tricks to turn personal opinion into cultural appraisal.

Collective intelligence algorithms work well with star rating systems and tags. These are popular methods for rating books, films and music on ecommerce and review sites. They can be represeented, aggregated and extrapolated from easily by software, which makes them ideal for representing opinion in SchellingCoins. There are risks in using such systems, as the low rating of the film “Gunday” on IMDB shows, but they are easy and accessible to use.

Digital Humanities approaches often involve counting the frequency of words in texts or other unstructured phenomena. The results of binary checks or of counts can be applied to Schelling coins. For example, whether an artwork appears on CAD or Rhizome or not, or whether the words “blue” or “postbinary” appear the most in reviews about it on major review sites can be reported via further SchellingCoins or via trusted feeds or oracles.

To turn these approaches into a SchellingCoin, we do not ask what people think of an artwork. We ask them what they think the average reviewer will think of the artwork (or to protect against gaming, we ask them to predict the curve for all the star ratings for the work). Given the theory of focal points, the most likely answer is the one that people suspect will be true.

Cultural SchellingCoins can therefore function as aggregators of opinion-about-opinion-about artworks, producing qualitative but consensual evaluations and critiques of works of art that contain more information than purely price-based mechanisms. Using SchellingCoins to aggregate opinion about other schellingcoins, Meta-SchellingCoings, can provide more general cultural critique.

To turn reviews into art criticism with a longer or broader perspective we can ask people not what the current state of reviews of the artwork but about what they will be in a year’s time, five years’ time, etc. How highly starred will they be and what tags/words will be used to describe them? Will the work (or the artist) be used as a point of comparison in reviews and articles? Will it (or they) still be being exhibited or purchased, and in what kind of galleries? How much will the work sell for, or in the absence of sales how many people will visit it at exhibitions? Will the artist still be working in that style, or how will their work have changed?

Each prediction can be represented as a security in a prediction market, and the current price of that security can be interpreted as the probability of that prediction. For example, a prediction market security might reward a hundred Satoshis or ten points if a particular artist has a headline show at Tate Modern. If you think there’s an 80% chance of that happening, you can pay up to 80 Satoshis or 8 points for the security representing that prediction. If you’re right you gain in return for improving the market, if you’re wrong you lose instead. There is evidence that prediction markets are successful, although they have been banned as a form of gambling in the US and the Pentagon’s 2003 attempt at a political prediction market was quickly labelled a “terrorism futures market” by the press and taken offline.

There is already a successful cultural predicton market, Hollywood Stock Exchange, where the price of “shares” in actors, directors and movies function as a prediction of their performance at the box office. The art market itself can be considered a kind of hybrid prediction market, but separating out that predictive function into a pure prediction market concentrating on critical evaluation can remove distortions that result from manipulation of the secondary market and solve the problem of representing critically valuable artworks that aren’t part of the art market.

It’s also possible, as with Hollywood Stock Exchange’s use of directors and actors as well as movies, to have prediction markets for other artworld entities. Not just artists and galleries, but movements, styles, genres, subject matter, even formal and aesthetic properties such as colours can be represented as securities in a prediction market. Buying and selling them can help set a shared understanding of their potential and impact.

Prediction markets can be represented as Distributed Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) on Ethereum’s blockchain, free from central control. DAOs present an opportunity to re-think and re-implement organizations on the blockchain. As well as markets they can be used to manage events, publications, co-operatives and educational or artworld institutions on various organizational models in a public and transparent way.

Cultural SchellingCoins, Artistic Prediction Markets and Aesthetic Derivatives are Accelerationist technologies for art criticism. Not necessarily for art criticism of the kind that survives online after being exiled from print media. Rather a functional equivalent to it that recaptures its lost authority in the form of a relationship between individuals and artistic production that exerts a guiding hand on its reception and direction. As they represent an emergent ontology of art and aesthetics manipulating these technologies, whether through technical or social means, is itself art and art criticism.

The text of this essay is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

Featured image: Image from the movie ‘Frankenstein Conquers the World’ directed by Ishirō Honda, a 1965 Kaiju film.

“Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. … They are organs of the human brain, created by human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified.” [1] Marx (1857-8)

This writing roots out a few ideas concerning science and technological determinism and humanity’s bond with digital media and social networks. The themes are covered in terms loosely as to what they may symbolize. It looks at our fears relating to technology, human-machine relations, cyborgs, theories in cyber-culture, classical and SF literature and contemporary art practices across the fields of media art, hacktivism, activism, feminism and cyberpunk.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the focus for this text but it also brings into the mix, Greek mythology and Prometheus – the Titan, and what the myth symbolizes, asking, in what form does he exist in the world today? It is a playful assemblage of unresolved contemplations that have been sitting around asking for light in the back of my mind. This is a stripped down version of the original study about mythology, technology, fear and revolution.

Humans have always exploited the raw materials this planet has to offer, and has the power to change the nature of things, whether it is physical or virtual. With constant re-edits and enhancements we transform everything we touch and this is all part of our evolutionary mutation. [2] The word ‘technology’ originally comes from the Greek word tekhne, meaning art and craft, the making of useful or good things. The ‘ology’ part means to discuss something or a branch of knowledge and common form. In Greek Mythology Prometheus was a demigod and a Titan worshiped by craftsmen. “In Greece the Titans were ultimately honoured as the ancestors of men. To them was attributed the invention of the arts and magic.” [3] (Graves 1964)

First, we begin with an apocalyptic vision of what could be and what it looks like when something strange occurs in the oceans. In July 2011, an article in the International Business Times featured a phenomenon we’d normally expect in a science fiction novel or movie. The headline read “Millions of Jellyfish Invade Nuclear Reactors in Japan, Israel” [4] Then the Reuters news web site mentions another jellyfish invasion at a Scottish nuclear power plant, in Torness. “An invasion of jellyfish into a cooling water pool at a Scottish nuclear power plant kept its nuclear reactors offline on Wednesday, a phenomenon which may grow more common in future, scientists said.” [5]

![Dauphin Island Sea Lab. [7]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/127544-millions-of-jellyfish-invade-nuclear-reactors-in-japan-and-israel.jpg)

On whether this occurrence is significant and poses future threats, the International Business Times said, “The several [power plant] incidents that happened recently aren’t enough to indicate a global pattern. They certainly could be coincidental, Monty Graham, a jellyfish biologist and senior marine scientist at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab off the Gulf Coast of Alabama stating, told LiveScience.” [7] However, some say jellyfish may be the only species worth fishing in European waters if trends in overfishing are allowed to continue. In an article in the Telegraph in 2008, it said, “scientists have said that unless the system is completely overhauled fish stocks will continue to deplete to the point of extinction by 2048, leaving consumers little option but to eat jellyfish or the small bony species left behind at the bottom of the ocean.” [8]

In September 2013 another mass of jellyfish forced one of the world’s largest nuclear reactors to shut down. The Operators of the Oskarshamn nuclear plant in Sweden had to scramble one of their three reactors after tons of jellyfish clogged the pipes that bring in cool water to the plant’s turbines. “By Tuesday, the pipes had been cleaned of the jellyfish and engineers were preparing to restart the reactor, which at 1,400 megawatts of output is the largest boiling-water reactor in the world.” [9]

“New research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that the rise in jellyfish populations may not only be aided by climate change, but is also contributing to it by making oceans more acidic, thereby disrupting their function as carbon sinks.” [10] (Land 2011)

Since the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 trust of a state’s handling of dangerous technology has taken a dive. We need only to look at Japan’s recent experience of technological disaster with their nuclear power stations. This brings us to the notion of risk and what this means. In the 19th Century risk was no longer about nature, it changed, it extended to us humans and our conduct. “This extension was due in part to the singular appearance of the accident, a kind of mix between nature and will.” [11] (Ewald 1993) […] Thus “no progress without associated damages.” [12]

Gareth Edwards, director of the 2014 Godzilla movie, starts with a 10 minute recap of “nuclear bomb tests from Bikini Atoll featuring voluminous apocalyptic mushroom clouds and a full-blown Fukushima-like nuclear power meltdown.” [13]

Since the 19th century fears about technology and the notion that scientists are meddling with creation itself has been in the public’s consciousness. Many view Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as triggering these long-term concerns. Of course, these fears are subjective, but also include people’s concerns about not having control over how technological decisions are reshaping society. After all, many lives have been lost due to brilliant uses of technological advancement made specifically for the act of killing many, as with the development of nuclear and biological weapons.

“Two international treaties outlawed biological weapons in 1925 and 1972, but they have largely failed to stop countries from conducting offensive weapons research and large-scale production of biological weapons.” [14] (Frischknecht 2003)