Lift up Your Heads,

O Ye Gates

An Appreciation of David Daniels 1933 – 2008

http://www.thegatesofparadise.com/

Click here for Tributes to David Daniels by Divers Hands

This article is co-published by The Hyperliterature Exchange and Furtherfield.

David Daniels, who died in May 2008, was a shape-poet. Between 1984 (when, already in his fifties, he first began to create picture-poems) (1) and the year of his death, he produced three huge sequences of work: The Gates of Paradise, Years and Humans.

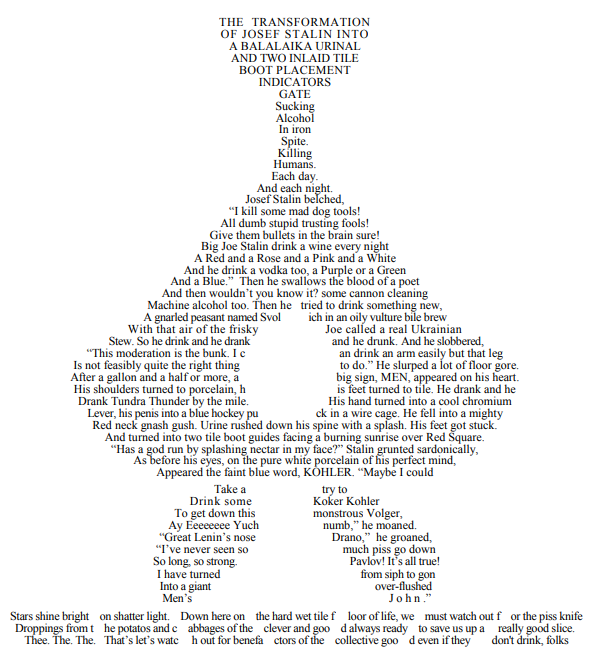

The Gates of Paradise contains over 350 poems, each of which, according to Daniels’ Introduction to the project, is “an icon of our world… that exhibits some of the ways I’ve seen living and dead human beings struggling to find happiness inside themselves and outside of them… My idea is to nourish the buried real human inside…” They are poems about people and their states of mind, sometimes satirical, sometimes visionary and sometimes obscene.

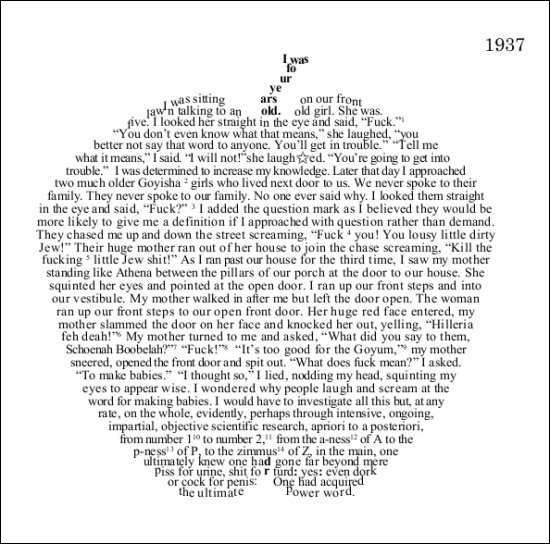

The Years sequence comprises one poem for every year of Daniels’ life (up to 2002 when the project was completed), plus one extra poem set in 2133 after his death. Many of the poems are autobiographical, but 1962 is almost a poem apart, or rather a novella, complete with narrative, multiple characters and dialogue. This section was described by Daniels as “a mini epic, 70 pages long, [which] I wrote in sonata form” (2). 1962 had a special significance for Daniels, because it was the year when “Earth became a technicolor Oz for me due to a sea change in my life that led me into a permanent inner joy” (3).

Humans, Daniels’ final project, is a sequence of 200 poems based on the lives, writings and biographical details of 200 individuals – some living, some dead, some of them relatives or friends of Daniels, some his fellow-artists, and some known to him through his reading. Again, as in The Gates of Paradise, his concern is with the inner lives of his subjects, and his treatment of those inner lives ranges from satire and hilarity to visionary intensity – sometimes within the space of the same poem.

What is shape poetry? In his preface to Years Daniels writes: “David Daniels has been making words out of pictures and pictures out of words for over 60 years” – which is probably as good a description of his art as any. Shape poetry (also known as concrete poetry, visual poetry or pattern poetry) is poetry in which the actual shapes of the words and letters make an important contribution to the meaning of the verse. Some of the earliest examples, cited as influences by Daniels himself, are the “pattern poems” collected in The Greek Anthology, where the text forms the shapes of an axe, a pair of wings, an egg, and so forth (4). Another much-cited example is “The Mouse’s Tale” by Lewis Carroll (from Alice in Wonderland), which resembles a long wavy tail, with the font-size gradually becoming smaller and smaller towards the end so that the tail dwindles to a fine point. This latter example is particularly relevant to Daniels, firstly because it displays a quirky sense of humour, and secondly because it manipulates not just the position of words on the page but the way in which they are displayed – the font-size – to achieve its effect. Thirdly, there are the Calligrammes of the French experimental poet Guillaume Apollinaire (5), published in 1918 shortly after his death, where the words (sometimes handwritten) form pictures such as the Eiffel Tower and a woman in a hat.

Concrete poetry established itself as a “movement”, complete with its own manifesto, in Brazil in the 1950s (6), and it’s no coincidence that Daniels’ work was greeted with much enthusiasm by the Brazilians Regina Celia Pinto and Jorge Luis Antonio; but whereas the concrete poets of the fifties argued their case in theoretical terms (“Concrete poetry begins by assuming a total responsibility before language… it refuses to absorb words as mere indifferent vehicles…” (7)), Daniels himself preferred to account for his chosen style in terms of his background and personal inclinations:

When I was little sometimes I wished I was looking at pictures when I was reading books. And sometimes I wished I was reading words when I was looking at pictures. I was probably prejudiced by films which were pictures that spoke words. When I wrote I wished I could write pictures. When I painted I wished I could paint words. (3)

He was also influenced by his family’s involvement with print:

My father’s four brothers were printers in Newark, New Jersey… My Uncle Nathan… would sit at this huge line-o-type machine and type in things and out would come typeset. I was only there once and I watched him and I said, “Nathan, what are you doing?” He said, “I’m writing a poem.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “It’s just nothing, it’s just a poem for someone, someone wants a poem for their wedding.” So he was typesetting poems and I might have got the idea from that.(2)

If the first quote hints at Daniels’ visionary and experimental tendencies – his love of magical transformations and his impatience with received form and its constraints (“When I wrote I wished I could write pictures. When I painted I wished I could paint words.”) – the second suggests other important aspects of his work: a fascination with craftsmanship and process, and an interest in the intersection between art and technology.

Daniels always freely acknowledged the importance of technology to his art:

Some people have tried to create shape poems with a typewriter. No one could write the shapes I write without a computer.(3)

“I use Microsoft Word, I started in 1984. I started off with Microsoft Word and every new Microsoft Word, I’ve had to redo everything I’ve done until the latest one because it has gray shading, unless they come out with something that makes things move.”

“And at that time, I began to come under the influence of the Internet. I had never had the internet before and someone named Mark Peters started sending me these weird poems where people had taken things off the internet and assembled them. So people started sending me at that time, I guess it was 1994/95, this amazing lists of things, jokes, dirty words, things that have happened, slang, everything under the sun… I just took them and put them into my works.”(2)

Daniels is one of those figures who straddles the divide between digital and pre-digital art and literature. His emphasis as an artist was always on process and practice rather than concept and theory, and for that reason he was never inclined to insist, as some new media artists and writers do, on the fundamental differences between the page and the screen, or between a virtual image and a painted or printed one. In new media terms, his output was fairly low-tech. His work was never interactive, generative or otherwise coded. As far as I know he never involved himself in programming: he simply used the Microsoft Word software-package as he found it, for his own purposes. On the other hand he clearly had a very detailed grasp of Word’s capabilities in terms of text layout and presentation, and he used it with a craftsmanship of which his Uncle Nathan would have been proud:

And then there are subtler things where you need to get a line to go up so if there is a word like light or elevation, you can by raising it 5 point, _ point (sic), 1 point you can get a word to get up or down and then when people read it, it affects them the way meter works.(2)

His shape poems achieve their effects through the strategic use of different fonts, font-sizes, ranging, kerning, bold type, italics, upper and lower case and (perhaps most importantly) empty space. He could make a block of text look like a human being, an elephant, a pyramid, a sunset, a tree, a pointing finger or a griffin. Until you’ve actually tried to do the kind of things he did it’s quite difficult to understand the attention to detail and the technical expertise involved. But he wasn’t content simply to perfect his skill at making shapes out of words. In his last work, Humans, he took an important step away from the paradigm of the printed page, and began to exploit the possibilities of the computer as a display-medium in itself – firstly by adding multiple colours to his pages (both text and backgrounds), secondly by building them into sequences which could be viewed as stop-frame animations, and thirdly – right at the end of his life – by adding sound.

His claim to be thought of as a digital artist, if it matters, rests partly on these late experiments: but it also rests on the enthusiasm with which he embraced the Web and was embraced in his turn by other experimental writers working online. According to his entry on Wikipedia (8), he described a web artist as “a human or a machine that pours out his/her/its soul on the internet” – in other words he didn’t think web artists were defined by any particular medium or artform, but by their use of the internet as a means of dissemination. On the other hand, his account of how he used material from the internet in his work (“people started sending me… everything under the sun… I just took them and put them into my works”) has an authentic new media ring to it – the author as an assembler of online “found” materials. He was also like a lot of other digital artists in his enthusiasm for the open source, copyleft principle of making work available online for nothing: “My art is available in .pdf form FREE at my website. Why should I wait around for no one to buy it?” (9) He was delighted to allow UbuWeb (http://www.ubu.com/) to display both The Gates of Paradise and Years in their entirety. In the same way, in 2004 he allowed Regina Celia Pinto to publish all he had completed up to that time of the Humans project (10), and promised her that she could have the whole thing when it was finished.

http://www.thegatesofparadise.com/tgop_pdf/198gate.pdf

http://www.thegatesofparadise.com/tgop_pdf/198gate.pdf

His friendships with Regina Pinto of The Museum of the Essential (http://www.arteonline.arq.br/) and with Kenneth Goldsmith of UbuWeb are examples of the connections he made, and the high regard in which he was held, within the digital arts community. As well as UbuWeb and The Museum of the Essential, his work was also featured in Deluxe Rubber Chicken (http://www.thegatesofparadise.com/chicken/six/contents.html), Drunken Boat (http://www.thegatesofparadise.com/drunkenboat/daniels/daniels.html), Iowa Review Web (http://www.uiowa.edu/~iareview/tirweb/feature/sept04/index.html), Xerolage (http://xexoxial.org/xerolage/x34.html) and Whalelane (http://www.thegatesofparadise.com/GOP_whaleline/whaleline_index.htm). The names of digital artists featured in the Humans project give some idea of how well-regarded he became in the new media field: Alan Sondheim, Jim Andrews, Mez, Ana Maria Uribe, Barry Smiley, Lewis Lacook, Joel Weishaus, mIEKAL aND, Michael Szpakowski and so on. Many of these connections were made via the WebArtery e-mail group, which he joined in 2001, and to which he continued to post items of interest and comments about other people’s work until within a few weeks of his death. When the members of this group heard (via Joel Weishaus) that Daniels was terminally ill, the list was flooded with messages of regret and appreciation, and one noteworthy aspect of this reaction was the number of webarterians who remarked that they had been looking at his work again and realising what an achievement it was.

So what was it about his shape poems which commanded such respect from his peers? It wasn’t simply the quality or technical mastery of his page-design or the excellence of his writing: it was the vitality, variety and inventiveness of his output, along with its ambition and scale. As Michael Basinski remarks in his interview with Daniels, “Unlike other visual poetry that is minimalist, your work is narrative.” In fact Daniels’ work mixes poetry and prose together with complete freedom, but his shape-poems are certainly very wordy compared with most other artists working in the same tradition. It is significant in this regard that Daniels professed not to like very much poetry. He claimed that he started writing poetry of his own when his son Chris “gave me a book called The Stuffed Owl which is an anthology of bad verse by good writers edited by D. B. Wyndham Lewis. It’s the poetry I first read that I ever liked. It was just so easy to read and it was so interesting.” (2) The writers he admired tended to be novelists – ” I have a very good ear for writing because when I hear things, I think of Dickens, Hemingway, and all these people” (2) – Dickens was obviously a particular favourite; and the 1962 section of Years certainly shows a novelist-like talent for character, dialogue, description, social milieu, multiple viewpoints and so forth.

But despite his protestation that he preferred bad poetry to good, there are clear links between his work and the Romantic movement. For one thing, he was obviously an admirer of William Blake. Before Daniels used it, The Gates of Paradise was already the title of one of Blake’s later and lesser-known works; and his admiration for Blake is made clear in the interview with Michael Basinski (2):

Anyone who… tries to make a masterpiece is considered a lunatic weirdo. That’s what my best friends call me… Well, Blake was like that… He was considered a total idiot. And let’s hope he was.

My son… told me, dad, wait until they see this, no one’s ever written their life story in pictures. People are going to be in awe. They’re going to think you’re like Blake.

It’s easy to understand why Daniels would have felt drawn to Blake: an outsider and revolutionary who insisted on producing his work in a completely idiosyncratic way, despite its lack of critical or commercial success; a self-publisher who put a great deal of craftsmanship and technical expertise into his books along with a great deal of invention; and an artist who was equally gifted as a poet and a picture-maker. But there is another point of similarity too: Blake was a visionary. He believed that most human beings spent their lives repressing and denying the divinity that dwelt within them. His work is complex, but it is unified by a single message: that people should free themselves from the “mind-forg’d manacles” which imprison them, and realise their true potential.

Daniels worked in very much the same spirit. He believed that humanity was divine, but its divinity was often repressed and twisted by upbringing, society and circumstance. In 2000 he described The Gates of Paradise to John Strausbaugh (11) in the following terms: “they’re gates to inside a person. And also paradise is really inside people – happiness.” And in his 2004 interview with Jorge Luiz Antonio and Regina Celia Pinto he developed the same theme in a way which brings to mind not only Blake but the Wordsworth of “Intimations of Immortality”:

When children are born they are a fine invisible engine as soft as the mirror on a pool of silk water inside a clumsy automobile. As they grow they crash in accidents and get dents and scrapes and road dirt all over their automobile. They are trained to forget they are an invisible engine inside… Whenever they say – “I have an invisible engine”… they are told that they are crazy, or to go on a boring drive they hate…

Compare this with Wordsworth’s lines:

Thou little child, yet glorious in the might

Of heaven-born freedom…

…Full soon thy Soul shall have her earthly freight,

And custom lie upon thee with a weight,

Heavy as frost, and deep almost as life!

One thing which separated Daniels from Blake and Wordsworth alike, however – apart from his atheism – was that his work was frequently very funny, and just as it freely mingled poetry and prose, it also balanced its visionary qualities with moments of startling earthiness. Here, for example, is an extract from the 1962 section of Years:

“Get your goddam hands off the shoulder, farm boy! Fuck you in the teeth with a blow torch, you greenballed grandmother raping goddam cock sucking son of a bitch.”

and here is an extract from his last completed Human, Shane Morgan Seavey, published in March 2008:

Shane Morgan Seavey loves Milk: Burping: Farting: Mommy: Daddy: Grandpa: Grandma: Nana: & Papa: Bella: & Buster: And his giant world famous railroad tunnel of giant shits…

http://www.thegatesofparadise.com/tgop_pdf/198gate.pdf

http://www.thegatesofparadise.com/tgop_pdf/198gate.pdf

Of course, Daniels’ work will not be to everyone’s taste. He never made any secret of the fact that he was trying to write masterpieces (“Why doesn’t anyone want to do anything important anymore?”), and this in itself imposes a barrier between him and those theoreticians who argue that the age of the masterpiece is dead. He isn’t a concept artist: in many ways he is a throwback to the old Romantic idea of the artist as an inspired individual, a kind of prophet who can see through our drab materialism to the inner truths it obscures. He also belongs in the American tradition of bardic experimentalists, along with Whitman and Ginsberg (although he professed not to like Ginsberg).

Like Whitman and Ginsberg, he can be prolix. Because he made up words to fill out the typographical shapes he was creating, there is an element of “padding” to his writing, and he often uses a kind of sing-song word-association of indefinite length: “And now I will say farewell to you: And I will sing of another jolly work loving level headed warm breaded friend making householding drawing sketching painting designing building far corner of the world azure cobalt navy sapphire…” At its best this has an improvisational quality like jazz, but at its weakest it can become reminiscent of the “lipsmacking thirstquenching ace tasting motivating Pepsi” advert.

Another potential weak-point is that, because Daniels’ pictures were made of lots of small words rather than a few large ones, it is always difficult to appreciate them as pictures and as writing both at the same time. In effect they separate out into two layers, and probably the best method of looking at them (on the computer-screen) is to reduce them in size and enjoy them as pictures first of all, then increase them in size and enjoy them as writing afterwards. Only once they have been looked at in both these ways does their full unity of design become apparent. This separation into two different layers became even more emphatic in the Humans project, when Daniels began to combine lots of similar pages with the same text on them into long sequences, to create stop-frame animations. But after all, the same criticism – that the design can only be appreciated by detaching yourself from the text, and the text can only be appreciated by detaching yourself from the design – can be levelled at illuminated manuscripts, and it doesn’t prevent them from being amongst the best-loved artefacts of mediaeval culture. The objection is a theoretical one, which tends to become insubstantial when you absorb yourself the actual work, because the same qualities of vitality and imagination come across from both the written and pictorial aspects. One leads you to the other, and his unique artistic personality seems to emerge equally from both.

In the last analysis Daniels’ flaws are part of his artistic personality. His freewheeling verbosity is part of his energy and inventiveness, and it goes hand-in-hand with his imagination and humour. The fact that his art in some ways seems to be going in two directions at once, doing two different things at the same time, is an expression of his Protean quality, his impatience with received forms, his desire to create something uniquely his own. He wasn’t the kind of man who liked to work with a restricted pallette or hold himself in check for the sake of greater control and perfection. His art is about liberation, uninhibited outpouring, spontaneity and fun. It is a completely human art: its flaws are human flaws: and that’s exactly the way he would have wanted it.

Notes:

(1) See Interview with Michael Basinski (http://www.ubu.com/papers/daniels_interview.html): “I use Microsoft Word. I started in 1984 and really started writing in 84. I started Gates in 87.”

(2) Interview with Michael Basinski (http://www.ubu.com/papers/daniels_interview.html)

(3) Interview with Jorge Juis Antonio and Regina Celia Pinto (http://arteonline.arq.br/museu/interviews/david.htm)

(4) See Interview with Jorge Luis Antonio and Regina Celia Pinto, opus cited: “In the 1950’s I stumbled upon The Greek Anthology – Vol 5 – Loeb Classical Library – 1953 – Book XV – MISCELANEA EPIGRAM 21- The Pipe Of Theocritus- A picture of the pipe of Pan in words written about Pan.” The Greek pattern poems themselves can be seen at http://www.theoi.com/Text/PatternPoems.html.

(6) See, for example, the website of Augusto de Campos, a pioneer of the movement, at http://www2.uol.com.br/augustodecampos/home.htm

(7) Quoted in the Wikipedia article on concrete poetry, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concrete_poetry

(8) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Daniels_(poet)

(9) http://www.hyperex.co.uk/reviewpayments.php

(10) http://www.arteonline.arq.br/david/

© Edward Picot, October 2008