Leila Johnston was Rambert Dance company’s first ‘digital creative in residence’ from October 2015 – February 2016, having successfully applied to their residency programme, Sprint. The programme aims to enable Rambert to engage more deeply with the digital world, and is framed as experimental and light touch, with no expectations or goals in mind. One of the outputs of Leila’s residency – and the subject of this review – was a report ‘Hacking Rambert’, an incisive account of Leila’s time on Sprint, as well as a reflection on the nature of the creative residencies, dance and technology cultures.

Leila describes herself as an outspoken critic of current technology culture, resistant to its tendency for ‘digital evangelism’. The report belies her frustrations with technology culture – and indeed is a call to arms for rethinking what that culture needs to become. Her approach to the residency reflects this, emphasizing that its value came from bringing her critical perspectives about tech culture to bear, as much as from introducing dancers to ‘tools’ (though this played an important role too). She stresses how opportunities for growth and learning arose ‘through people (and sometimes tech)’ (my italics), and places human interaction and collaboration at the forefront, alongside, if not over and above, hardware and software. Dance is, she says, ‘about extraordinary relationships on every level – with yourself and then the little halo of space around you at all times, and then with greater and greater halos until it’s with everyone you meet.’ People are at the centre of her thinking and writing, and her residency was underpinned by questions such as ‘Is there a way to use technology to do justice to the human lifetimes that go into dance? Is there a way to dignify individuals, to invite confrontations with real people, to respect something other than the movement and acknowledge the part that individual experience plays in the construction of dance?’

Reflections on the cultures of the dance and technology worlds are also central to the report. Leila was struck by the relative openness and accountability of the dance world, which she saw as ‘a home that opens its doors to anyone that knocks’, in contrast to self-aggrandizing, solution-focused, often misogynistic digital world that is so well equipped to sell itself and its benefits. One of the observations that fascinated me most was about the different approaches to labour in the dance and digital worlds. For the former, hard work is a celebrated and central driver – dancers are ‘efficient’ because no work is seen as wasted. By contrast, the digital world wants to recover ‘free time’ by getting the hard stuff out of the way. While tech wants to make things easier – dance wants to make them harder – so that difficulties and limitation can be mastered and overcome.

The dominant tech world rhetoric that technology – coding especially – is ‘for everyone’ is thrown into relief by its absence in the dance world, where no one would expect ‘everyone’ to be a brilliant dancer, since this is something that requires a lifetime of grit and dedication as well as the right body and innate talent. Leila shows us that we can learn from the dancers’ dedication and commitment that ‘not everyone can do anything, and that there are pursuits that arise from the nuanced world of individual lifetimes and personal, emotional, motivation, the results of which don’t resolve into a formula’.

Although her emphasis was on criticality and personal relations, she drew on an impressive range of kit. She experimented with a thermal camera attached to her iPhone, which enabled her to explore a ‘dance of heat’. She observed that ‘the idea that dancers can be expressed as their invisible heat is strange, but absolutely real’.

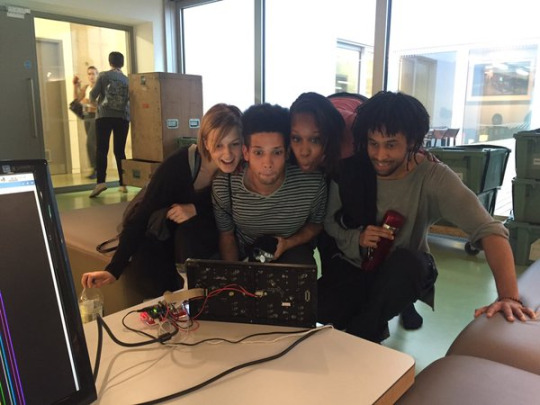

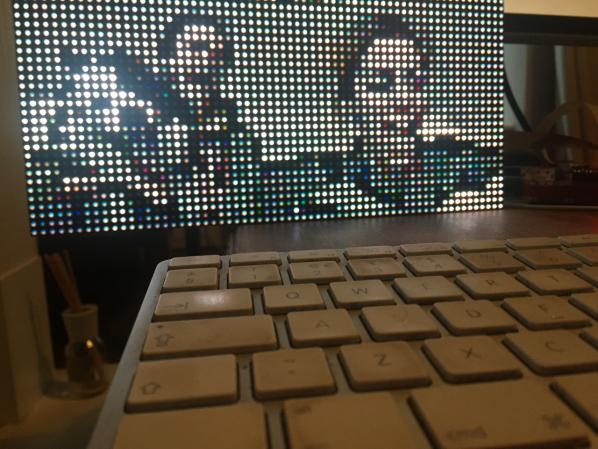

The Point Cloud demo on the Kinect was of great interest to the dancers, for whom it allowed a new kind of 360-degree vision, useful since they are ‘always looking for their own back’. Leila experimented with a Raspberry Pi, using it for a range of experiments including connecting LED panels where she could display words and video. Again though, as well as the tool itself, the Pi gave rise to critical reflection: ‘Why aren’t we teaching dancers and choreographers creative technology skills for their work, rather than reinforcing a hierarchy of expertise by ‘advising’ them on creative direction?’ Emphasizing how accessible and readily available Pis, LED panels and other technologies now are, Leila makes the point that maker culture can be embedded in the dance world at little cost, but this won’t happen organically unless more awareness of each other’s culture is fostered.

Drawing from the residency blog hackingrambert.tumblr.com, Leila reflects on time, truth, and difficulty. She is resolute that time, patience and commitment are needed to make meaningful artistic contributions, and that artists undertaking short term residencies need to be realistic about what can be achieved. Rather than gunning for a finished product, ‘short projects should be about making – what it means to be a creative, and what we learned about the best way to do things in the context of the artificially short creation time.’ Unlike the tech world, quick fix and solutionism will not fare well on a creative residency.

Leila’s reflections on the notion of truth are intriguing; she feels that there is ‘nowhere to hide’ in dance, and draws a parallel between dancers’ bodies and the ‘technical authenticity’ of circuit boards and wires. These forms of hardware offer respite from the slick interfaces that are so characteristic of digital technologies. She notes: ‘I’m interested in the relationship between truth and performance; the unique way in which (dance) performances are honest, how our bodies give away the truth, how things represent what they are very transparently’. These explorations of truth provoke rich questions about authenticity, identity, ‘fidelity’ and representation. The notion of the stripped back body is a striking one, and when one observes a dancer in motion, with their muscles, sinews, bones, sweat, and humanity on display, there can be a powerful connection between the dancer and the audience. However, there is artifice at work in dance too – creating illusions with the body, emphasizing certain lines, creating the appearance of fluidity and ease when the body is being pushed to its physical limits. Can we draw an analogy here to the performance of identity online, where the blood, sweat, tears and humanity are often glossed over with ‘choreographed’ images that appear spontaneous and perfect? Or is the truth of dance and bodies precisely an antidote to this phenomenon? My caution here would be that dancers have identities as well as bodies, and are not immune to the pressures placed on them about their appearance and representation.

Leila argues that the creative tech community needs to work harder to understand dance, but that dance too ‘has much to gain by creatively educating itself in the available tech options’. Introducing dancers and the dance world to creative technologies can be fruitful, but should not be understood in solutionist terms. Technologists must take responsibility for the enormous power they have in society – it is up to them to ‘educate and differentiate’ between the potentially homogenous mass that is ‘technology. Finally, she makes a case for ‘contemporary creative technology’. The notion of the contemporary connotes the historical nature of a given art form and the contingencies of its evolution – conceptually, technically, physically, socio-politically. The relative nascence of technology, she suggests, leaves it unanchored, and subject to the intentions of ‘commercial forces’. She states ‘A contemporary creative technology could lay down the microphone of narrative and exist in the depths of the present. We could stop writing our own story in the cultural canon – indeed stop telling stories about what we’re doing at all – and focus on being demonstrable and accountable.’

There are moments when Leila seems to idealize the dance world as relatively problem-free, without acknowledging its potential problems – not least the subjection of bodies to punishing regimes and the mental and physical problems this can give rise to, and issues of social inequality, accessibility and exclusivity that come with all creative industries. However, there is clearly a lot the technology world can learn from the culture of dance. Perhaps the tech sector should start having dancers in residence…