This article is co-published by The Hyperliterature Exchange and Furtherfield.org.

A short horror-game for adults, based on the Little Red Riding Hood folktale.

The Path is “a short horror-game inspired by the tale of Little Red Riding Hood” from Tale of Tales, an independent computer games development company, based in Belgium and run by Auriea Harvey and Michael Samyn. It was originally released in March 2009, and it represents Tale of Tales’ first attempt to produce a fully commercial computer game.

Harvey and Samyn’s output has always been driven by a desire to move away from the typical subject-matter and style of modern computer games, into territory which is more poetic and ambiguous, touching on deeper themes. Before they formed Tale of Tales they worked together under the name Entropy8Zuper! and produced work such as The Godlove Museum (texts from the Bible mixed with new media animations and social commentary). The first Tale of Tales project, 8, was based on the story of the Sleeping Beauty. The second, The Endless Forest, is a multi-player environment where each player controls a deer in an enchanted forest; and the third is The Graveyard, a meditation on old age and mortality, set in a cemetery, and featuring a little old lady on the point of death.

In many ways The Path‘s most obvious antecedent is 8 – in terms of its visual style and fairytale inspiration, not to mention the fact that the central character from 8, a girl dressed in white, actually reappears in The Path. But the game can also be seen as an inverted reworking of The Endless Forest, a release of the dark forces which were deliberately held at bay there. The Endless Forest is a completely safe environment because players are only able to communicate with one another through a limited range of gestures and the casting of spells – in effect, giving one another gifts. All the avatars are nominally male, since they are all stags, but essentially the game is sexless. In The Path, on the other hand, sexuality is one of the core preoccupations, and the fears that parents have about letting their children play on the Web – that they will be exploited and brutalised by sexual predators masquerading as playmates – hover in the background too.

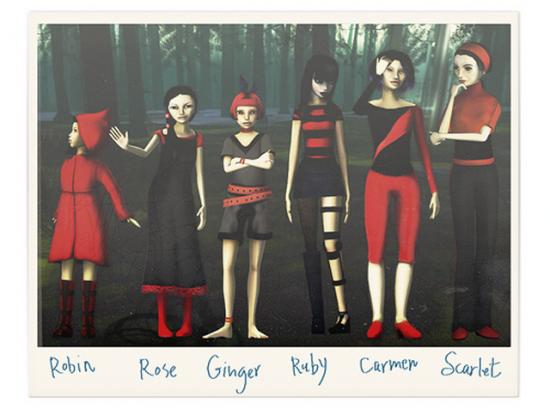

The opening scene of the game is a red room containing six girls, aged from nine to nineteen. Your task as a player is to select one of them and guide her along a path through the woods. Words appear on-screen as you begin: “Go to Grandmother’s house. And stay on the path.” You can only play the game to the full, however, if you disobey these instructions, leave the path, and venture into the trees. As soon as you do so the ambience of the game changes: the music becomes more ominous, and most of the colour disappears from the screen. Daylight is replaced either by deep shade or night. You begin to notice things between the tree-trunks: in fact, one of the most effective aspects of the game is the way in which you catch the glimpses of things far off in the wood, and they gradually reveal themselves more fully as you move towards them. There are gleaming white flowers; a running girl dressed in a white smock; abandoned objects such as an armchair, an old car, a bath or a broken television; and finally places, such as a ruined playground, a disused theatre, a field of flowers with a scarecrow in the middle, or a graveyard.

At certain points in the game, semi-transparent images loom up onto the screen, and if you let go of the controls your avatar will act of her own accord. If you place her close enough to one of the shiny flowers, for example, she will bend down and pick it. If you place her close enough to one of the abandoned objects in the wood, she may interact with it – although some of them will only interact with certain girls. She may pick up an old teddy-bear with two heads, or get inside an abandoned car. When this kind of interaction occurs, images and text-fragments appear on-screen, apparently dropping dark hints about your avatar’s ultimate fate, her past history or her inner life. For example when Ruby – the most Gothic of the girls, who wears a black brace on one leg – interacts with an old wheelchair, the following text appears:

Sitting on wheels. Paralyzed soul. Nowhere to go. Fast. Don’t come close if you want something from me. Whatever it is, I probably don’t have it. Just leave me alone.

The most potent form of interaction occurs when your avatar arrives at one of the special places in the wood, and meets her wolf. Each of the girls has her own particular wolf and will meet him if she goes to a particular place. Scarlet, for example – the oldest of the girls, lover of order, hater of mess, devotee of the arts – meets her wolf at the disused theatre. The following text appears: “Art is where the nobility of humanity is expressed. I could not live in a world without it.”

When a girl meets her wolf she is no longer under the control of the player, but swept up instead into a lengthy and sinister video-sequence which ends with a blackout. She “comes round” from this experience in torrential rain, just outside Grandmother’s house. The only thing left is to enter. Inside the house, which is dark, predominantly red and full of snarling noises, what happens depends on how many discoveries she has made in the wood. The more extensively she has explored, the more rooms she will be allowed to enter. Each room reveals a sinister and enigmatic tableau – a roomful of empty glass jars, an underwater table, or a wrecked automobile. After passing through a series of these rooms, your avatar must finally traverse a corridor decorated with a nightmarish damask pattern of spiky black leaves, until she comes to the last room, where she discovers both Grandmother’s bed, and a whole sequence of split-second images, often images of bleeding or dismemberment, which seem to half-reveal some terrible experience she is undergoing or has already undergone, possibly her rape and murder.

If you restart the game you will find yourself back in the red room where it began, but this time there is one less girl in it. In order to play the game properly all the way through, you need to take each girl in turn through the woods to Grandmother’s house.

The Path is by no means flawless. One really serious problem is its slowness. Samyn and Harvey make a virtue of this (“The Path is a Slow Game” they point out on their website), and the game’s slowness certainly does help them to build up atmosphere and tension; but there comes a point at which suspense tips over into boredom and frustration. Perhaps the most glaring example is the plank bridge leading to Grandmother’s front door, which seems to take an eternity to get across.

Furthermore, the fragments of text which appear from time to time are effective at pointing up the main character-traits of the avatars, and reinforcing the main themes of the game, but the quality of the writing is functional rather than inspired. Here is Ruby, the Goth, at the rusty car:

Engines. And friends. Turn them on. Turn them off. Life. Death. Are they so different?

Here is Scarlet encountering an old armchair:

A serenade in the woods. Somebody is playing my song. Long slim fingers gently caressing the keys of me.

Here is Robin at the disused playground:

I see-a-saw. Slide-the-hide. Go round the merry. And swing-along.

The first expresses isolation, cynicism and nihilism; the second an aesthetic and poetical nature; and the third a little girl who wants to play. They do their job, but they all sound rather contrived – a point which is best illustrated by comparing them with a text-fragment that really works, this one from Robin, when she picks up an old hunting-knife:

I’ll have to be very careful with this and not run any more.

This sounds much more like something that a little girl would actually say, but it’s also much more psychologically convincing: Robin knows that she shouldn’t be playing with the hunting-knife, but she thinks she can make it all right by promising herself to be extra-careful. We immediately feel convinced that her good resolutions won’t last long – and the sense that she is doing something she shouldn’t be doing, allowing her curiosity about forbidden things to get the better of her common-sense, is relevant to the larger themes of the game. She should never have left the path in the first place. The text makes us more acutely aware of both her vulnerability and her naive expectation that things will be all right.

There is also a hint of woodenness to certain aspects of the graphic design. In general the playing environment of The Path is a visual triumph – the woods, the special places in the woods, the path itself, and best of all Grandmother’s house, which is both quaint and sinister on the outside, and downright frightening on the inside. Some of the special objects, however, are less convincing – an old boot and an old record-player come to mind in particular – and although the female avatars are all very well designed, one or two of the male “wolves” are not, especially the wood-cutter and the man at the disused playground, both of whom look comical rather than sinister from certain angles.

Another criticism which could be levelled at The Path is that although it is full of hints and clues, musical climaxes and visionary moments, which seem to suggest that secrets are being glimpsed and hidden truths uncovered, everything in it remains nebulous and unexplained, the clues don’t really lead anywhere, we never actually learn anything concrete about the girls or their wolves, and ultimately all we are left with is the unpleasant message that the quest for experience leads to trauma, and the quest for love leads to sexual brutality. The counter-argument to this, however, is firstly that the game derives its goriness and suggestions of rape from the tale on which it is based – a tale which goes right back into folklore, and thus into the depths of the human psyche – and secondly that by keeping their story nebulous and suggestive rather than explicit and detailed, Samyn and Harvey prevent The Path from becoming a mere puzzle-game with a fixed solution. In this way the imagination of the player is freed rather than tied down, and the symbolic aspects of the game-narrative, which are its real strength, are allowed to come to the surface.

Certain elements of the Little Red Riding Hood tale are missing from The Path altogether. One of the best-known aspects of the tale – the sequence in which Red Riding Hood comments about her wolf-grandmother’s appearance in tones of rising astonishment: “What big eyes you have”, “What big teeth you have”, and so forth – has vanished. But although the tale has been simplified and truncated in some respects, it has been opened out in others, because Samyn and Harvey have incorporated references to various different versions of the tale instead of confining themselves to one in particular. The two best-known versions are by Charles Perrault (who turns it into a fable about avoiding sexually voracious men) and the Grimm Brothers (who place more emphasis on the dangers of being distracted from the paths of duty) – but there are numerous others. Sometimes Red Riding Hood meets not a wolf but an ogre; sometimes she is asked to choose which way she would like to take to Grandmother’s house, the path of needles or the path of pins; sometimes, when she gets to the house, she is fed various parts of a dismembered grandmother; and sometimes she is commanded to join the wolf or ogre in bed, first performing a striptease and throwing her clothes onto the fire.

In The Path, the gleaming flowers which lead us deeper and deeper into the trees are a reference to the pretty flowers which distract Red Riding Hood in the Grimms’ version, amongst others. Samyn and Harvey also incorporate references to the path of needles and the path of pins in some of their texts. More importantly, they retain the gruesomeness, the allusions to dismemberment, and the violent sexuality which feature in many earlier versions. And the symbolism which lurks beneath the surface of Red Riding Hood in all its various manifestations comes through particularly strongly. First of all, of course, there is the symbolism of a path through tangled woods – the same symbolism with which Dante’s Divine Comedy opens:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

che la diritta via era smarrita.

(Midway this way of life we’re bound upon,

I woke to find myself in a dark wood,

Where the right road was wholly lost and gone.)

The road or path represents virtue, civilization, safety, a sense of purpose and direction – whereas the wood represents sin and error, wilderness, danger, the unknown, bewilderment and confusion. Aspects of the same symbolism can be found in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress: in fact it is a commonplace of Christian iconography. Beyond this lie other meanings: the road represents the known whereas the wood represents the unknown; so, by extension, the road represents the conscious mind and logic, whereas the wood represents the unconscious, emotions, desires and dreams. Samyn and Harvey reinforce these associations by having the path daylit, whereas the wood is always shrouded in darkness.

The beginning and end of the game are also interesting from the symbolic point of view. We begin in a red room, and we end in the red interior of Grandmother’s house. Red is the key colour in the game: all the girls are dressed in red, and all their names play on the same theme – Robin, Ginger, Carmen (Carmine), Ruby, Scarlet and Rose. Red is the colour of blood, and therefore signifies both life and death. We never see the mother at the beginning of the story, but in a sense she is there nevertheless, because the red room from which all the girls start their journey can be interpreted as a womb-symbol. What about the horrific red house where all the journies end? On one level the journey the girls make is from innocence to experience, especially in the sexual sense, and Grandmother’s scary house represents the terrors of adulthood, life with all the pleasantries stripped away. But on another level, the house where Grandmother lives – the house where all our ancestors live – is the grave. The girls in the story are thus like red corpuscles of life, journeying from the red starting-point of the womb to the red vanishing-point of death.

Needless to say this is all very far removed from the subject-matter of most computer games. Traditional adversarial games (such as Space Invaders, PacMan or Mario Brothers) are all about the triumph of the individual over difficult circumstances; their aim is to stimulate adrenalin, their requirements are concentration and dexterity, and their message, if they have one, is that winning is good and you can achieve anything if you try hard enough. In recent years the adversarial model has lost a certain amount of market share to games such as The Sims or Animal Crossing, which are more to do with exploring and integrating in a social milieu; but their messages still tend to be upbeat and uncomplicated – you can earn lots of money, get a better house, acquire lots of friends and so forth if you just try hard enough. Importantly, in these “social interaction” games, it is left up to you, as a player, to create your own narrative. By contrast, in The Path, we find ourselves in an environment which is drenched in symbolism, where the message is anything but upbeat, and where the story already exists. Your task as a player is not simply to explore the game’s environment but to experience it – in the same way that you might explore and experience a poem or a piece of music. In the process you are also unearthing the narrative which lies buried within the game. This game is not about the virtues of self-application, willpower, quick reactions and an acquisitive nature: it is about sexuality, the darker side of human nature and the price we sometimes pay for experience. It is a game which could never have been conceived by one of the big commercial companies, and which could perhaps never have been made in the USA at all, steeped as it is in European folklore and sensibility.

As regards the commercial success of The Path, Samyn and Harvey are unable to release full sales figures at the moment, due to the nature of their contract with their main distributor, Steam; but they comment that

…we need to pay back the 90,000 Euro loan (+ interest) we got from the governmental investment company CultuurInvest. And we’re happy to say that it looks like we’re going to make it. The total budget of The Path, however, was quite a bit bigger (but financed mostly by non- or less commercial art grants). And it’s far from certain if we will actually be able to make that much back.

Conventional marketing wisdom about The Path would undoubtedly be that it is hardly likely to succeed in commercial terms, because it gives itself too many disadvantages to start with. A game based on a fairy-tale is sure to appeal primarily to young children or parents with young children: The Path, on the other hand, despite its fairy-tale origins, insists that it is designed for adults. It’s also a game about girls (a disadvantage in itself), and about girls who succumb to the wolves in the wood rather than overcoming them; and despite its billing as a horror game, it’s long on atmosphere and short on visceral thrills. In other words it disqualifies itself from success with the mainstream gaming audience (teenagers and young adults, predominantly male) by virtue of its subject matter, disqualifies itself from success with a minority audience (younger children and their parents) by virtue of the way in which that subject matter is handled, and disqualifies itself from success with any gamers left over by being too “arty”, slow-moving and downbeat.

These may seem like very crushing considerations, but if you boil them down, like a lot of marketing wisdom, what they amount to is the assumption that nothing will sell if it doesn’t fit neatly into a pre-existing category, or if it deals with its subject-matter in an unconventional way – to put it more simply, that nothing will sell if it doesn’t imitate something which has sold already. Ultimately this kind of “wisdom” is self-defeating, and leads to nothing but stagnation.

The conclusion Samyn and Harvey themselves draw from their experiences with The Path is a positive one: “Apparently you can sell art to gamers now.” They may not have produced a huge commercial success, but they haven’t produced a flop either – and this is an achievement in itself, given their unconventional approach. And it probably isn’t desireable that The Path should become a huge commercial success in any case, since this would only be likely to produce an outbreak of Path imitations. What is more important is that Tale of Tales should continue to produce new and challenging work, demonstrating that the rules of conventional games-design are not written in stone, and that it is possible to design games which are poetic and expressive but still viable in the marketplace. If they can do this for long enough, then undoubtedly other independent games developers will be inspired to follow their example, and their influence over the evolution of games design in the next few years may well be a profound one.

Available via download for Mac or Windows at $9.99, or on USB for Mac or Windows for 25.00 Euros.

copyright – Edward Picot, August 2009.