We live in a world riddled with contradictions and confusing signals. Our histories are assessed, judged and introduced as fact yet there are so many bits missing. We accept what is given through soundbite forms of mediation and end up using the easy bits as our defaults, and build up these assumptions as our ‘imagined’ guidelines. This article examines how these accepted defaults are being challenged by contemporary artists. Each have expressed their own particular (unofficial and official) form of interventions at the Tate Gallery. Featuring art works produced by artists’ and art groups, such as Graham Harwood, Platform, IOCOSE and Tamiko Thiel, we explore their connected enactments and critiques of the existing conditions. Whether it is based on economic, ecological, historical, political or hierarchical situations, they are making others aware of their creative arguments in different ways.

You will not see them accepting an award at the Turner Prize. But, their work has become as equally significant (perhaps even more) than, the mainstream art establishment’s franchised celebrities. There is now wider art audience out there, connected to the Internet and they are aware of the issues of the day. Yet, this context is not reflected back by traditional art venues and art press. Instead, we receive more of the same. The mainstream version of contemporary art has found its allies within a global and corporate culture, where business dictate’s art value. Critical and imaginative contexts contrary to neoliberal demands, are left aside. We cannot trust the ‘official’ art world to produce a realistic vision of what contemporary art really is. It is up those who are not reliant on or diverted by these powerful frameworks and elusive economies, to bring about a different set of examples of an existing parallel world which is thriving, and so much more interesting and relevant.

“Art is subject to a double protection. In the market, it is shielded from unwarranted treatment through controlled ownership. In the museum world, experts decide what should be seen, alongside what, with what interpretation and in what circumstances. A wide public is courted but allowed no power over what it sees. The very ethos of this culture—of exclusivity, elitism and control—is now at odds with the culture people make themselves.” [1] (Stallabrass 2011)

“From adolescence I had visited the Tate, read the Art books and generally pulled a forelock in the direction of the cult of genius, on cue relegating my own creativity to the Victorian image of the rabid dog. We know well enough that this was how it was supposed to be. The historical literature on ‘rational recreations’ states that, in reforming opinion, museums were envisaged as a means of exposing the working classes to the improving mental influence of middle class culture. I was being inoculated for the cultural health of the nation.”[2] (Harwood)

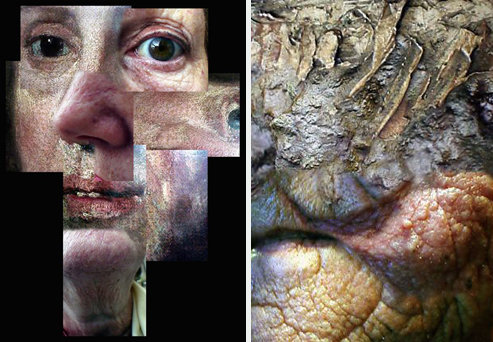

In 2000, Graham Harwood[3] received the first Net Art online commission from the Tate Gallery London for the creation of his art work ‘Uncomfortable Proximity'[4]. Viewing the visual images/collages created by Harwood; reminds one of the moment when Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray'[5] views his disfigured self portrait. Considered a work of classic gothic fiction with a strong Faustian theme. The facade of his own idealised beauty is revealed as something less attractive and deeply disturbing. Harwood’s approach in offering the viewer to click on the image to see what lies behind shows the people he represents, to be seen as lurking secrets, as ghosts, mutants, lepers and outsiders.

![Dorian in front of his portrait in the 1945 film The Picture of Dorian Gray.[6]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/dorian-gray.jpg)

“Tate Britain stands on the site of Millbank penitentiary incorporating part of the prison within its own structure. The bodies of many of the inmates remain concreted into the foundations of the building. The drains that run from the building to the Thames, a stones through away, bleed this decay into the silt of the Thames.”[7] (Harwood 2006).

Harwood brings to the fore the forgotten people. The lives of others, whose stories are now just distant markers of a past, dominated by a colonial history. These are the losers, the then ridiculed and exploited chavs of their day.

“‘Chav’ is an insulting word exclusively directed at people who are working class.”[8] (Jones 2012).

The first section of ‘Uncomfortable Proximity’ maps high society rituals of tastefulness and its inherent hypocrisy. The second, representations and histories of different people such as friends, family and others, who are unseen in terms of the institution’s remit of tastefulness. To do this he used the historically respected paintings (on-line images) on the Tate web site by artists such as Turner, Hogarth, Hamilton, Gainsborough, Constable and others.

“This work forced me into an uncomfortable proximity with the economic and social elite’s use of aesthetics in their ascendancy to power and what this means in my own work on the internet.”[9] (Harwood 2006)

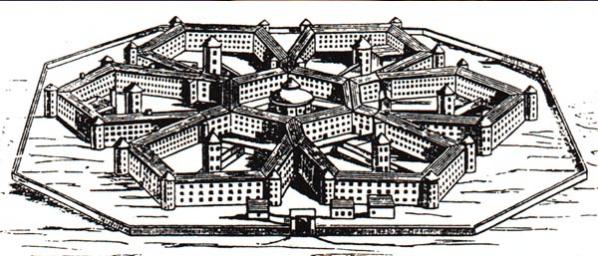

London’s Tate Britain area, before it was reconstructed into an art gallery, in the early 19th century was a national prison. The Millbank Penetentiary, was hailed as the greatest prison in Europe, at a cost of £500,000 it was finally built in 1821. It was Jeremy Bentham, the British philosopher and philanthropist who designed it using his pionering ideas creating the prison as a ‘panopticon’.

“At its centre was the Governor’s House, which allowed prison guards to keep watch over 1,500 transportation prisoners housed in separate cells in the surrounding pentagonal blocks. There were three miles of cold, gloomy passages: the turnkeys invented a code of chalked directions to stop getting lost in the maze!”[10]

Sentenced prisoners were processed in the prison each year and up to 4,000 would then be sent off to distant lands, such as Australia. Within the panopticon, prisoners would not know whether they were being watched or not.

“The panopticon Panoptic power built into the architecture of Benthams’ prison Prefigured what some refer to as the “electronic panopticon” or “surveillance society” which includes: the mass surveillance & collection of data by government on populations; the surveillance & collection of data on consumers for marketing purposes; the management surveillance & control of the workforce by industry.”[11] (Ballantyne)

Somehow Harwood manages to bite at the hand that feeds him, “the artist very deliberately used the work to question the role of digital media in promotion and collection. His Web site copied the Tate publicity site, with his own content inserted, causing substantial institutional disruption around the marketing department because the Tate’s Web site, in common with those of many art museums, was seen primarily as a marketing tool, then perhaps as interpretation, but never before then as a venue for digital art.[12] (Cook, 2001).

At his point it’s worth considering how some artists have experimented with the behaviour of parasites in order to explore their artistic autonomy at the edge of things. The rise of hacking and ‘art and hacktivism’ has brought about artists reimagining their creative intentions not in terms of existing within the frameworks of galleries and museums (although many do show their work in these types of venues as well). Many have chosen not to comply to the ‘official’ script of marketing demands and values imposed by mainstream art world hegemony, or concede to centralised web 2.0 structures dominating Internet culture and our mobile networks.

“The word ‘parasite’ comes from ‘para sitos’, meaning ‘beside the grain’, and refers to those animals that take advantage of grain stores to feed. […] they are not part of the restricted economy of exchange, profit, and return that is at the heart of capitalism, and to which everything else ends up being subordinated and subsumed. Thus they find an enclave away from total subsumption not outside of the market, but at its technical core.”[13] (Gere 2012)

![Haw under arrest before the State Opening of Parliament in 2010. Photo: Jeff Moore. Telegraph.[14]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/haw-police_1924712b.jpg)

In June 2001, activist Brian Haw began his protest against the economic sanction on Iraq, opposite the Palace of Westminster in central London, until his death of lung cancer in June 2011. He earned himself a place in the history books for what he devoted ten years of his life doing, camping in a tent outside the Palace with numerous placards. First it started with only a few banners and then through the years the number of banners accumulated, with its content pointing out to the public and politicians, the huge suffering and killing of people in Iraq supported by the UK government. “Even as fresh attempts were begun to oust him, he won an award for being that year’s ‘most inspiring political figure’.”[15] (Stevenson 2011)

In 2006-7 British artist Mark Wallinger created an installation called State Britain, replicating all of the tents and banners at Parliament Square. Featuring it as his main entry for the Turner Prize at Tate Britain. “Faithful in every detail, each section of Brian Haw’s peace camp from the makeshift tarpaulin shelter and tea-making area to the profusion of hand-painted placards and teddy bears wearing peace-slogan t-shirts has been painstakingly sourced and replicated for the display.”[16] It also included copies of other people’s contributions, consisting of messages and banners amassed by Haw over the years, as a constant and dedicated daily protester, winning Wallinger the Turner Prize.

“…the larger hand-painted signs are defanged by their new context. “Beep for Brian,” once an irreverent call-to-arms taken up by many motorists plowing through the Westminster traffic, has become an absurdity, un-honkably sealed within the echoing marble box of the Tate. Never has the notion of the “lost original,” that timeworn legacy of Duchamp’s ready-mades, carried such a melancholic charge.” [17] (Street)

In contrast to his peers who also came out of the YBA (BritArt) movement in the late 80s and early 90s, which includes individuals such as Damien Hirst, Rachel Whiteread and Tracey Emin, Wallinger is a committed socialist. Damien Hirst was “the leading light in the YBA movement, is a famously good businessman and is now one of the richest men in England.”[18] (Shaw 2011)

“I did feel removed from the YBA thing. But it almost immediately raised people’s game. There was money and there was an audience. Or, to be strictly accurate, there was money – it really was a very targeted strategy to begin with – and the audience came along a bit later.”[19] (Wallinger 2011)

Wallinger’s comments about the audience coming along later rings true. The power of money and marketing created an audience that before,was not there, specifically for the YBA’s. Emerging artists at the time, who were not part of this elite where left out of the picture, not because of their art but because of their lack of connections with YBA circles. Many artists casted their creative intentions and values aside and re-invented their art in accordance to YBA themes, with a hope they would be accepted by this (then) new, mainstream art establishment. From the early 80s, and well into the 90s, UK art culture was dominated by the marketing strategies of Saatchi and Saatchi, a formidable force in the advertising world. The same company had been responsible for the successful promotion of the Conservative party (and conservative culture) that had led to the election of the Thatcher government in 1979. Saatchi and Saatchi Applied their marketing techniques and corporate power, with an accomplished parallel coup within the British art scene, creating an elite of artists who embraced the commodification of their personalities alongside depoliticized artworks.

Stewart Home proposes that the YBA movement’s evolving presence in art culture fits within the discourse of totalitarian art “the critics who theorise the yBa understand that by transforming art into a secular religion, rather than a mere adjunct of the state, liberalism imposes its domination over the ‘masses’ far more effectively than National Socialism. The focus, especially in the mass media, must be on the artists rather than the artwork.”[20] (Home 1996)

“To be an artist is to contend with the present, and there are not many other careers that afford the freedom to radically examine life and society. To put it bluntly, if artists are studying and writing more about politics, culture, and education, it’s probably a reflection of the unprecedented dysfunctionality of the societies in which they live.”[21] (Deck 2005)

Every now and then something slips through the highly taught institutional web of marketed ideologies and it causes a state of ‘healthy’ unease. One such intervention is the recent collaborative project Tate à Tate.[22] It is a public intervention consisting of an audio guide that people can download onto their MP3 players or mobile phones. The material is accessible from http://tateatate.org – you download a selection of audio files and then take a physical tour to Tate Britain. It is best experienced if you take the Tate Boat to Tate Modern, or you can listen at home. The artists selected to make the sound works are Ansuman Biswas, Phil England, Jim Welton, Isa Suarez, Mark McGowan and Mae Martin.

Mark McGowan, through his daily and weekly online video broadcasts on Youtube and Vimeo, has gained a large Internet-based audience. His videos have appeared on the BBC and the Russia Today news channel. He is a performance artist and constant ‘angry’ critic of the UK government. He has never voted and, is equally critical towards whatever party happens to be in power at the time. Mcgowan’s antics have received interest because of the directness of his arguments. He speaks for and to those who do not have a voice. He reflects upon unjust situations happening in real life. He has become an alterantive force to a ‘politically’ corporate media, who offer no way in for those are not already connected with the elites of institutionalized power.

McGowan, has caused various controversies. In 2007, during Celebrity Big Brother when Jade Goody made what seemed to be racists remarks to her house-mate Shilpa Shetty; he publicised an event in support of Goody, which was a protest to burn an effigy of shetty. In the end did not take place.

His position, was that working class people were being used by the media as product to feed a machine, exploiting everyday people’s vulnerabilities. It is also an attack on the media invention of ‘Chavs’, a deliberate attempt to demonise the working classes of Britain. In retrospect, many viewed incident on Celebrity Big Brother as a clash of classes, and not necessarily a rascist issue. But, it was all too late, the media took control of what it saw as a chance to create a larger spectacle out of an already bleak situation.

“The media despised her. […] ‘Vote the pig out!’ demanded the Sun, which also referred to her as an ‘oinker’. Others taunted her as a vile ‘fishwife’ and ‘The Elephant woman’. As the campaign became a hysterical witch-hunt (indeed, one fo the headlines was: ‘Ditch the Witch!’), members of the public stood outside of the studios with placards reading: ‘Burn the Pig!’.” [23] (Jones 2012)

Dominant ideologies are cultivated hegemonically as part of the mainstream consciousness. And even though, the messages communicated through these channels do not accurately reflect real life, they do reflect stereotypes and easy packages of soundbite items on a cruder (lack of) understanding of what human values are, indivudally and collectively. These ‘mediated’ structures, socially re-construct according to ‘commercialised’ trends rather than looking at deeper resonances. Which should also include a necessary critique of their own roles and responsibilities, aksing what does it do to the psyche of a culture when you creating a spectacle out of the everyday; from fantasy into a permanant state of hyper-reality for profit?

“The poverty of the accepted culture and its monopoly on the means of cultural production lead to a corresponding impoverishment of the theory and manifestations of the avant-garde. But it is only within this avant-garde that a new revolutionary conception of culture is imperceptibly taking shape. Now that the dominant culture and the beginnings of oppositional culture are arriving at the extreme point of their separation and impotence, this new conception should assert itself.” [24] (Debord 1957)

In art, in politics, and in all avenues of power in our culture, the working classes have no voice. It seems that the only way to claim personal power is by submitting to the embarrassing scenario of applying as a contestant on what is ironically termed as reality TV. and, this involves singing someone else’s already ‘bland’, tedious songs, usually written by corporate music media. The divide of class is ever present as colonial systems prevail in exploiting not only foreign resources and the destruction of indigenous peoples’ histories and their ways of living; but also in the very states and countries where these corporate ‘friendly’ neoliberalist cults reside. In respect of oil and funding of the arts, Tate à Tate pulls these issues out from being hidden into a mainstream dialogue through their own interventions.

As the markets have gained an increasingly tighter hold on global economics and everyday people’s lives, a rise of international protests has also gained impetus. We have the Occupy protests which have spread from Wall Street to London to Bogota, in over 950 cities in 82 countries. We also have the UK Uncut protest movement challenging the government’s austerity cuts. The Internet has been a valuable medium, allowing people to connect and organise together. This has enhanced crossovers where artists have become activists and activists artists. New forms of ‘networked’ and ‘activist’ expression, exploiting the imaginative skills of artists (and others) has brought brought about a mix of ideas once used by the Situationists. If you are a typical gallery attendee or a purchaser of mainstream art magazines, awareness of current political and ecological issues through these cultural interfaces are rare. Interventionist art challenges this standard. Causing a social anomaly, fracturing the facade of what we are usually informed of as ‘national’ value.

Tate a Tate is a collaboration between the groups Platform, Liberate Tate and Art Not Oil. The work was a response to when BP was promoting its sponsorship activities in the run-up to the 2012 Olympics. Against the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the Royal Opera House and Tate Britain, aligning themselves with BP (British Petroleum). By receiving sponsorship from BP they say these institutions are “legitimising the devastation of indigenous communities in Canada through tar sands extraction, the expansion of dangerous oil drilling in the Arctic, and the reckless business practices that lead to the deaths of eleven oil workers on the Deepwater Horizon. BP’s involvement with these institutions represents a serious stain on the UK’s cultural patrimony.”[25]

Mel Evans, Platform: “Tate à Tate began from a creative impulse to install something somehow immovable in Tate. Platform and Liberate Tate were collaborating on the publication ‘Not if but when: Culture Beyond Oil’, which features international artists work in response to the BP Gulf of Mexico catastrohpe, and sets out the key debates on oil sponsorship of the arts. We had noticed our critics were often alluding to a kind of inevitability of BP sponsorship.”

“Liberate Tate’s spectacular performances, although headline grabbing, had all been swiftly cleaned up by Tate staff. Although we knew tough questions were being asked by the Board of Trustees, and 8,000 members and gallery-goers had petitioned Director Nicholas Serota to drop the sponsorship, we also wondered to what extent Tate could absorb our efforts into its own politically savvy artistic persona. So the idea of an audio tour seemed the perfect way for us to create a permanent installation in Tate, challenging BP’s continued presence in the gallery, and recreated by every participant that takes the free download and goes ‘undercover’ in Tate.”

“The process began with a call out for proposals which received a terrific response. From this we came down to three proposals that we thought were equally fantastic and sufficiently different to all warrant exploration – which is where the three chapter journey was born, from Tate Britain to Modern via Tate Boat. From the launch in March 2012 onwards we quickly learned that participants were keen to pick a favourite of the three, their choices were hard to predict.”

“For some, the water related narratives in ‘This is Not An Oil Tanker’, created by Isa Suarez featuring Mae Martin, Mark McGowan and Jasmine Thomas, make the piece the most emotive experience. Others prefer the structure and highly informative content of ‘Drilling the Dirt (A Temporary Difficulty)’ by Phil England and Jim Welton, and likewise other tastes feel most comfortable in the more meandering and evocative ‘Panaudicon’ created by Ansuman Biswas. Panaudicon by Ansuman Biswas at the Tate Britain is by far the most successful… its interaction with and interpretation of its environment is a lot more complex. As initiators of a project with which we want to reach diverse audiences, we’re glad there’s something in there for everyone.”

![Winner of the recent Greenpeace Rebrand BP Competition. Designed by Laurent Hunziker [26]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/rebranded.jpg)

You can understand why questions around the Tate’s association with BP is of utmost importance. Especially, when considering the oil company has had as many as 8,000 oil spills in the USA alone. There is a long list of disasters and much information linking BP’s troubling courtships with oppressive regimes. Shell, BP, Exxon, Gazprom, Rosneft and other companies, as I write this, are engaged in a frenzied rush in the Arctic risking yet another oil spill and threatening us with even more climate change. And all this effort is for only three years worth of oil.

‘”For over 800,000 years, ice has been a permanent feature of the Arctic ocean. It’s melting because of our use of dirty fossil fuel energy, and in the near future it could be ice free for the first time since humans walked the Earth. This would be not only devastating for the people, polar bears, narwhals, walruses and other species that live there – but for the rest of us too.” [27] (Greenpeace 2012)

Recently in 2012, BP agreed to pay the largest criminal fine in US history for its corporate negligence, in causing the catastrophic Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. “This was a disaster for the record books: The offshore exploratory well was the deepest drilling ever, plunging more than 30,000 feet through ocean and seabed strata, and the spill was the largest in U.S. history, spewing 206 million gallons of oil — nearly 20 times what the Exxon Valdez had dumped into Prince William Sound in Alaska a decade earlier.” [28] (Schiffman 2012).

In 2011, the New Orleans, LA. Attendees of the ‘Gulf Coast Leadership Summit’ witnessed a positive statement from a representative of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as he announced to everyone’s surprise a ban on toxic dispersants, and a new free health care plan for spill and cleanup victims. Not just that, there was also another progressive announcement by the BP co-presenter that day who publicly expressed regret for his company’s past actions, he said the oil giant would also pay the bill for the new health care plan.

Of course, it was all to good to be true. it was a hoax by the Yes Men [29].

“…except for the audience, everyone was a fake. The impostors Dr. Dean Winkeldom and Steve Wistwil, both Gulf Coast residents, collaborated with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade[30], an organization whose goal is to create sustainable communities free from industrial pollution. The organization decided to create a hoax to publicize what should be happening in response to the emerging health crisis.” [31] (Flaherty 2011)

“The Louisiana Bucket Brigade action was supported by the Yes Lab, a project of The Yes Men that helps activist groups carry out media-getting creative actions on their own. Four years ago in New Orleans, The Yes Men impersonated an official from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to announce, among other things, that HUD would re-open public housing and make oil companies pay up for wetlands destruction.”[32] (ibid)

Morgan Quaintance reviewed it for Art Monthly and found that “the Tate Britain and Tate Boat works suffer from a confused sense of purpose… on the other hand, England and Welton’s Tate Modern piece is a note-perfect subversion of the standard form.

Meanwhile Kate Kelsall reviewing for Don’t Panic online reported “There is something irresistibly subversive about slinking around an establishment with your headphones in, taking orders from a voice that resembles a TomTom or sleep aid recording…

Jonathan Jones, after the Tate had renewed its deal with BP wrote in an article in the Guardian “Oh, give me a break. The campaign to stop Tate, the National Portrait Gallery and other museums from accepting money from Britain’s controversial petroleum outfit is the stupidest and most misplaced of supposedly radical campaigns. Why not do something useful like join Occupy? While protests around the world this year, from Wall Street to Tahrir Square, have picked the right causes and enemies, the BP art campaign is mistargeted, misconceived and massively self-indulgent.”