Walking off the Akadimias district and onto the steps leading up towards the entrance of building number 23, I am greeted by a large hall with high red ceilings. The hall is covered with lavish white and black dot marble, and there is a large staircase acting as a guide to the top floors of the manor-like building. This was the home for the Diplomatic Centre of the Third Reich, designed in 1923 by Vassillis Tsagris, and used until 2011 by the Foreign Press Correspondent Union after the Second World War. Since then it has stood derelict and dusty, but for one week, in parallel to the opening of documenta 14, it played temporary host to the artist-in-residence programme of Palais de Tokyo, alongside with Foundation Fluxum/Flux Laboratory, bearing the name Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Six visual artists in residence at Pavillon Neuflize OBC and eight contemporary Greek choreographers envision and fabricate a hybrid space whereby an experimental notion of a community is executed as a situation rather than as a subject. The visual artists and performers involved congregated together in Athens and on site for a two-week workshop in March in order to produce the works. The title, Prec(ar)ious Collectives, is a linguistic amalgamation of the adjectives ‘precarious’ and ‘precious’, implying the state of the collective that performs together.

The opening façade echoes with the humming and reverberated sound of Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos‘ Dusk and Dawn Look Just The Same (Riot Tourism), guiding us towards its installation room. The video installation stands above a mountain of blue powder in a room sectioned off with construction tape. The short sequence of about a minute and a half displays a group of hooded figures, dressed identically. As the soundtrack’s volume begins to escalate, the group progresses from walking to running on the uncannily void and ghostly streets of Athens. A city always bustling with noise is now at its most quiet and pubescent state of the day – dawn. The hooded figures run together and – even though it is in a disordered manner – command your attention and pensiveness until they all reach Omonia Square. The work demonstrates a resistance to a status quo which may be aligned with the political engagement within the city. This is not, however, done in an expected reactionary manner, but instead in a way that promotes uprising through the creation of a meditative state. One cannot help but watch Lemos’ work a couple of times more before leaving it behind and only then noticing the thundering beneath their feet.

This historic building has a basement and is the temporary home of Taloi Havini‘s performative work. The large-scale installation occupying four rooms consists of PVC vinyls, seemingly discarded or hung from the low ceiling. These PVC vinyls are lit by dispersed and differently coloured strings of light, some are red, others are purple and others are cream. The performance is underway and its performers dress themselves with the PVC vinyl and the lights and jolt their bodies vigorously to the rhythm of the thundering – sometimes in sync, sometimes not. The dark basement is transformed into a cavern of rhythmic delight alluding to a ritual where its power lies in the gathering of people.

As one inspects the garments of Wataru Tominaga and those who wear them, this synthesis of the PVC, the space and the performers as a gathering appears to be a motif. Tominaga created the garments during a preliminary workshop, with great care and appreciation of how he and others were to utilise them during Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Originally presented on mannequins before being worn and performed, the garments boast vivid colours and patterns, some of them containing animalistic features such as feathers or fur. Those who wear Tominaga’s work perform in such a way as to invent a new form of communication between themselves and their observers. They move and conjoin like animals, sometimes hiding underneath the fabric and at times evoking the traditional Japanese ‘snake dance’. The performance, being in a transitional space between the ground floor and the first floor, naturally spreads itself upstairs whereby the performers not only continue to wear the garments in obscure ways, but additionally interact with Yu Ji‘s agave plants and other objects.

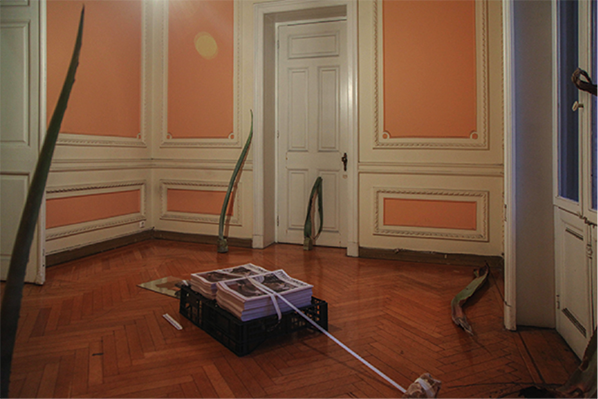

Yu Ji‘s work, Lycabettus Tongue, Oliv Oliv and This is Good For You! Are formed by the use of displaced agave plants, half-fragmented found mirrors and lights. The agave plants interlock with various architectural patterns of the building such as stair banisters, whilst the mirrors and round-ball lights are positioned in ways offering various points of view for observation and appreciation of space. The work revitalizes the architecture of the building denoting its historical vitality and the synergy of the encompassing works into a haunting existence rather than an abandoned one. Here, haunting is used not for means of negative connotations but instead as a form of aloof yet introspective sensation, exasperated further with Lola Gonzàlez‘s video installation in the next room.

Lola Gonzàlez‘s Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw begins with its protagonists split into groups and observing the city of Athens from various points at the top of the hills. The groups begins to move, run and hop together towards a direction down the hill, whilst a chorus of droning voices begin to chant and harmonise. As the groups get closer and closer to the city, Gonzalez transforms the image into a complete inversion, like one you may find in negative photography. The chanting becomes louder as the three groups get closer and closer to their meeting point within the city – the exact space where the video is being showed. They are finally shown entering the building and making their way up the stairs to the room where they vocalize in unison until they fade away from our view. Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw alludes to an atmosphere in which the power of gathering together evokes a community whose intention is situated between an uncertain balance of peril and strength. It is the same kind of uncertainty that one finds when exploring the top floor of the building only to discover Thomas Teurlai‘s room of machines and looped functions.

On the top floor, there are still the remnants of neglect, rooms empty of anything but the garbage that piled up over the building’s six years of desertion. Thomas Teurlai‘s Score for bodies and machines consists of a room installation of two printers used by the performers to scan different parts of their bodies. These scans are then plastered on the wall whilst the fluorescent lights constantly trickle on and off. The two performers are attempting to archive as much of the movement involved in their choreography as possible. The looped function of copying and the crackle of its repetitive working-noises do not clash with the choreography but instead drive its energy.

Indeed, it may be the encounter between the building, the communal working spirit of the performers and the result of this effort that defines this rejuvenating energy as a fruitful rebirth of the building’s utility.

To find out more, read Chloe Stavrou’s recent interview with Fabien Danesi of Prec(ar)ious Collectives.