test test

hello world!!!

hello world!!!

hello world!!!

By taking into account the unique characteristics of your target audience and tailoring your chatbot names accordingly, you can enhance user engagement and create a more personalized experience. Kore.ai also focuses on security and compliance, crucial for sensitive sectors like banking and healthcare. Analytics and reporting tools provide insights for optimizing customer service strategies. The platform’s adaptability across different industries, from banking to healthcare, helps businesses streamline processes and enhance customer interactions. Kore.ai’s free trial option allows businesses to evaluate the platform’s fit with their specific needs. Overall, Kore.ai positions itself as a comprehensive solution for creating and managing AI-driven customer interactions, aiming to improve efficiency and customer satisfaction across various sectors.

But don’t let them feel hoodwinked or that sense of cognitive dissonance that comes from thinking they’re talking to a person and realizing they’ve been deceived. Tidio’s AI chatbot incorporates human support into the mix to have the customer service team solve complex customer problems. But the platform also claims to answer up to 70% of customer questions without human intervention. A good chatbot name will tell your website visitors that it’s there to help, but also give them an insight into your services. Different bot names represent different characteristics, so make sure your chatbot represents your brand.

Many advanced AI chatbots will allow customers to connect with live chat agents if customers want their assistance. If you don’t want to confuse your customers by giving a human name to a chatbot, you can provide robotic names to them. These names will tell your customers that they are talking with a bot and not a human. AI chatbot platforms are indispensable tools for modern businesses, providing a blend of automation, efficiency, and personalized customer experiences. The landscape of leading AI platforms offers a wealth of options catering to every business’s journey into the digital age. Recognized by industry authorities and backed by significant investment, Yellow.ai aims to deliver empathetic, human-like interactions, leveraging advancements in NLP and generative AI.

It can be used to offer round-the-clock assistance or irresistible discounts to reduce cart abandonment. Selecting a chatbot name that closely resembles these qualities makes sense depending on whether your company has a humorous, quirky, or serious tone. In many circumstances, the name of your chatbot might affect how consumers https://chat.openai.com/ perceive the qualities of your brand. However, naming it without considering your ICP might be detrimental. You may discover a helpful chatbot to help you on their website, social media, or any other channel, whether it be in the fields of healthcare, automotive, manufacturing, travel, hospitality, or real estate.

For example, New Jersey City University named the chatbot Jacey, assonant to Jersey. Try to use friendly like Franklins or creative names like Recruitie to become more approachable and alleviate the stress when they’re looking for their first job. For example GSM Server created Basky Bot, with a short name from “Basket”.

Being an AI recruitment chatbot, Ideal increases candidate interest, eliminates pointless phone interviews, and quickly qualifies candidates. You can streamline and prioritize candidate interviews by automating 70% of your top-of-funnel interactions. Like other AI chatbots, Ideal also recommends practical insights to streamline your hiring process. Featuring Live agent handovers and integration with social media platforms, Smartbots also aims to make the experience of automating HR as simple as possible.

Humans are becoming comfortable building relationships with chatbots. Maybe even more comfortable than with other humans—after all, we know the bot is just there to help. Many people talk to their robot vacuum cleaners and use Siri or Alexa as often as they use Chat PG other tools. Some even ask their bots existential questions, interfere with their programming, or consider them a “safe” friend. For example, a legal firm Cartland Law created a chatbot Ailira (Artificially Intelligent Legal Information Research Assistant).

The platform’s strength lies in its natural language processing (NLP) capabilities, allowing for human-like conversations in multiple languages. It also supports integration with SAP and third-party solutions, enhancing the user experience across various business applications. Built on Google AI, it supports rich, intuitive conversations and offers a development platform for chatbots and voicebots.

Being a simple and robust chatbot builder platform, Hubspot chatbot builder lets you expand and automate live chat conversations. Customers can navigate the website, look up answers to frequently asked questions, and make appointments. Your CRM will retain their responses, enabling you to qualify prospects and turn on automation. Workativ’s smart HR chatbot focuses on streamlining employee support leveraging conversational AI technology and workflow automation.

You can turn the brainstorming session into a competition if you like, incentivising participation and generating excitement. You could also involve your customers by running a competition to gather name suggestions, gaining valuable insights into their perception of your brand. Or create a shortlist of names you like and ask the public to vote for their favourite. Internally, the AI chatbot helped Stena Line teams with cost-analysis systems.

And if you did, you must have noticed that the names of these chatbots are distinctive and occasionally odd. Typically, HR helpdesk chatbots are implemented on a variety of platforms for communication, including workplace intranets, websites, messaging services, and mobile apps. Online business owners also have the option of fixing a gender for the chatbot and choosing a bitmoji that will match the chatbots’ names. Apple named their iPhone bot Siri to make customers feel like talking to a human agent. In a business-to-business (B2B) website, most chatbots generate leads by scheduling appointments and asking lead-qualifying questions to website visitors.

In this section, we have compiled a list of some highly creative names that will help you align the chatbot with your business’s identity. Let’s consider an example where your company’s chatbots cater to Gen Z individuals. To establish a stronger connection with this audience, you might consider using names inspired by popular movies, songs, or comic books that resonate with them.

The ProProfs Live Chat Editorial Team is a diverse group of professionals passionate about customer support and engagement. We update you on the latest trends, dive into technical topics, and offer insights to elevate your business. This list of chatbots is a general overview of notable chatbot applications and web interfaces.

We all know what happened with the Boaty McBoatface public vote, but you don’t have to take it that far unless you want the PR. Simply pull together a shortlist of potential chatbot names you like best and ask people to vote from those. You can run a poll for free using Survey Monkey, LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp and/or any other channel you choose. Gartner projects one in 10 interactions will be automated by 2026, so there’s no need to try and pass your chatbot off as a human member of your team.

The platform stands out with its unique voice flow feature, enabling real-time voice virtual assistants and Interactive Voice Response systems. Botpress’s active community, boasting over 15,000 members, further enriches the user experience with shared knowledge and support. Overall, Botpress is an excellent platform for both novices and professionals in creating customized, AI-driven chatbots. The likes of the Quebec Government, Windstream, Husqvarna, VR Bank, and many others have adopted Botpress to build conversational AI applications for their customers or employees.

When customers first interact with your chatbot, they form an impression of your brand. Depending on your brand voice, it also sets a tone that might vary between friendly, formal, or humorous. When customers see a named chatbot, they are more likely to treat it as a human and less like a scripted program. This builds an emotional bond and adds to the reliability of the chatbot.

That’s the first step in warming up the customer’s heart to your business. One of the reasons for this is that mothers use cute names to express love and facilitate a bond between them and their child. So, a cute chatbot name can resonate with parents and make their connection to your brand stronger.

You can foun additiona information about ai customer service and artificial intelligence and NLP. For travel, a name like PacificBot can make the bot recognizable and creative for users. The mood you set for a chatbot should complement your brand and broadcast the vision of how the pain point should be solved. That is how people fall in love with brands – when they feel they found exactly what they were looking for. It’s true that people have different expectations when talking to an ecommerce bot and a healthcare virtual assistant.

Innovation can be the key to standing out in the crowded world of chatbots. From innovative, unique identities to playful cute names and even technologically-inspired options, there’s a world of ideas to set your creative juices flowing. Start with a simple Google search to see if any other chatbots exist with the same name. So you’ve chosen a name you love, reflecting the unique identity of your chatbot. This could be the perfect way to show off your chatbot’s capabilities, manage user expectations, and ensure they know they are interacting with AI. Remember, the name of your chatbot should be a clear indicator of its primary function so users know exactly what to expect from the interaction.

The nomenclature rules are not just for scientific reasons; in the digital age, they can play a huge role in branding, customer relationships, and service. Therefore, a good chatbot name can significantly ai chatbot names enhance your customer relationship, engendering loyalty and encouraging repeated visits. The positive impact of a well-chosen chatbot name on customer relationships can’t be underestimated.

It presents a golden opportunity to leave a lasting impression and foster unwavering customer loyalty. So far in the blog, most of the names you read strike out in an appealing way to capture the attention of young audiences. But, if your business prioritizes factors like trust, reliability, and credibility, then opt for conventional names. A 2021 survey shows that around 34.43% of people prefer a female virtual assistant like Alexa, Siri, Cortana, or Google Assistant. To truly understand your audience, it’s important to go beyond superficial demographic information. You must delve deeper into cultural backgrounds, languages, preferences, and interests.

A name that accurately embodies your chatbot’s responsibility resonates with your customer personas and uplifts your brand identity. A chatbot may be the one instance where you get to choose someone else’s personality. Create a personality with a choice of language (casual, formal, colloquial), level of empathy, humor, and more.

Gemini has an advantage here because the bot will ask you for specific information about your bot’s personality and business to generate more relevant and unique names. If you want a few ideas, we’re going to give you dozens and dozens of names that you can use to name your chatbot. You want to design a chatbot customers will love, and this step will help you achieve this goal. If it is so, then you need your chatbot’s name to give this out as well. Read moreCheck out this case study on how virtual customer service decreased cart abandonment by 25% for some inspiration. Let’s have a look at the list of bot names you can use for inspiration.

However, there are some drawbacks to using a neutral name for chatbots. These names sometimes make it more difficult to engage with users on a personal level. They might not be able to foster engaging conversations like a gendered name. Giving your chatbot a name helps customers understand who they’re interacting with. Remember, humanizing the chatbot-visitor interaction doesn’t mean pretending it’s a human agent, as that can harm customer trust.

Giving such a chatbot a distinctive, humorous name makes no sense since the users of such bots are unlikely to link the name you’ve picked with their scenario. In these situations, it makes appropriate to choose a straightforward, succinct, and solemn name. If we’ve aroused your attention, read on to see why your chatbot needs a name. Oh, and just in case, we’ve also gone ahead and compiled a list of some very cool chatbot/virtual assistant names. Ideal is an AI chatbot that leverages the power of AI to quickly and accurately shortlist thousands of new applications.

It helps HR organizations engage talent at scale, automate time-consuming HR tasks easily, and efficiently collect more data. Companies can improve employee lifecycle management with conversational AI-powered HR chatbots, from hiring to onboarding to career development. In this blog, we would like to draw your attention to the top 20 HR chatbots that are redefining employee support and experience in and beyond. However, you can resolve several common issues of customers with automatic responses and immediate solutions with chatbots. Now that you have a chatbot for customer assistance on your website, you must note that they still cannot replace human agents. Consider creating a dedicated day for brainstorming with your support teams to come up with a list of names.

The names can either relate to the latest trend or should sound new and innovative to your website visitors. For instance, if your chatbot relates to the science and technology field, you can name it Newton bot or Electron bot. For instance, you can implement chatbots in different fields such as eCommerce, B2B, education, and HR recruitment. Online business owners can relate their business to the chatbots’ roles. In this scenario, you can also name your chatbot in direct relation to your business.

Siri is a chatbot with AI technology that will efficiently answer customer questions. Online business owners use AI chatbots to reduce support ticket costs exponentially. Choosing a chatbot name is one of the effective ways to personalize it on websites. If you feel confused about choosing a human or robotic name for a chatbot, you should first determine the chatbot’s objectives. If your chatbot is going to act like a store representative in the online store, then choosing a human name is the best idea.

This chatbot is on various social media channels such as WhatsApp and Instagram. CovidAsha helps people who want to reach out for medical emergencies. In the same way, choosing a creative chatbot name can either relate to their role or serve to add humor to your visitors when they read it. Chatbots should captivate your target audience, and not distract them from your goals. We are now going to look into the seven innovative chatbot names that will suit your online business.

These names are a perfect fit for modern businesses or startups looking to quickly grasp their visitors’ attention. When choosing a name for your chatbot, you have two options – gendered or neutral. Setting up the chatbot name is relatively easy when you use industry-leading software like ProProfs Chat. Figuring out this purpose is crucial to understand the customer queries it will handle or the integrations it will have. A chatbot serves as the initial point of contact for your website visitors.

Keep in mind that the secret is to convey your bot’s goal without losing sight of the brand’s fundamental character. Phia can retrieve answers to your questions without the need to load FAQs when combined with the power of PeopleHum driving it or integrated with any backend HCM or HRMS platform that you prefer to use. Phia can intelligently search through instructions, procedure manuals, and other sources for schematic matches to find the most pertinent response to the query being asked.

ManyChat offers templates that make creating your bot quick and easy. While robust, you’ll find that the bot has limited integrations and lacks advanced customer segmentation. They can also recommend products, offer discounts, recover abandoned carts, and more. Tidio relies on Lyro, a conversational AI that can speak to customers on any live channel in up to 7 languages.

A study found that 36% of consumers prefer a female over a male chatbot. And the top desired personality traits of the bot were politeness and intelligence. Human conversations with bots are based on the chatbot’s personality, so make sure your one is welcoming and has a friendly name that fits. Creative names can have an interesting backstory and represent a great future ahead for your brand. They can also spark interest in your website visitors that will stay with them for a long time after the conversation is over.

A well-chosen name encourages more customer interaction and creates positive associations. The name should match your brand’s values, tone, and style to deepen the connection with your brand. Now you know how to name it too, you can transform your customer experience in no time at all. Since you can name your customer support chatbot whatever you like, deciding what to call it can be a daunting task. We’ve seen AI assistants called everything from Shockwave to Suiii and Vic to Vee. This digital adventure unfurled the significance of choosing the perfect chatbot name and opened doors to boundless ideas, strategies, and steps to achieve the same.

AI chatbots show bias based on people’s names, researchers find.

Posted: Fri, 05 Apr 2024 07:00:00 GMT [source]

Brevity, pronounceability, and relevant uniqueness are your maps to circumvent the mountain of complexity and the maze of unusualness, leading you toward a user-friendly and engaging chatbot name. While creating a unique and captivating chatbot name is essential, treading the fine line to avoid excessively complex or unusual names is equally significant. Better yet, perhaps you are inspired to carve out a path that uniquely mirrors your chatbot’s identity and offerings. Tech-inspired names are undeniably cool but don’t forget to factor in your end-users’ tech-savviness, so they can relate to and appreciate your chatbot’s innovative name. An innovative chatbot name can not only pique the interest of your users but also mark an impression on their minds, enhancing brand recall. This process promises an engaging chatbot name that aligns with your bot’s purpose, echoes with your audience, and upholds your brand image.

Do you remember the struggle of finding the right name or designing the logo for your business? It’s about to happen again, but this time, you can use what your company already has to help you out. Also, remember that your chatbot is an extension of your company, so make sure its name fits in well. Read moreFind out how to name and customize your Tidio chat widget to get a great overall user experience.

Woebot, for example, is a chatbot for the healthcare industry that can converse with patients, check on their mental health, and even provide tools and tactics to aid them in their present predicament. Ex-Google Technical Product guy specialising in generative AI (NLP, chatbots, audio, etc). Through Understandbetter.co, your HR department can capture, manage, and respond to employee feedback directly from Slack or Microsoft Teams. Employees are free to express their opinions to management at the company without worrying about discrimination. It also goes by the name of a personalized employee feedback system and provides managers with useful information about their direct reports.

Fictional characters’ names are an innovative choice and help you provide a unique personality to your chatbot that can resonate with your customers. When you are planning to name your chatbot creatively, you should look into various factors. Business objectives play a vital role in naming chatbots and online business owners should decide the role of chatbots in a website. For instance, if you have an eCommerce store, your chatbot should act as a sales representative. Since you are trying to engage and converse with your visitors via your AI chatbot, human names are the best idea. You can name your chatbot with a human name and give it a unique personality.

The same is true for e-commerce chatbots, which may be used to answer client questions, collect orders, and even provide product information. Eightfold is a modern talent management platform that specializes in assisting multinational corporations with recruiting and retaining a diverse workforce of workers, candidates, and contractors. Powered by deep-learning AI, Eightfold shows you what you need, when you need it. Eightfold gives people a better understanding of their career potential and gives businesses a better understanding of the potential of their workforce.

Additionally, it’s possible that your consumer won’t be as receptive to speaking with a bot if you can’t make an emotional connection with them. Make human-like interactions that encourage conversions and experiences. When users can answer multiple-choice and open-ended questions through the chatbot customization dashboard, you generate qualified leads and expand your sales pipeline. Rezolve.ai is a modern HR helpdesk that works within MS Teams to offer employees automated and personalized HR support via GenAI Sidekick HR Chatbot.

There are different ways to play around with words to create catchy names. First, do a thorough audience research and identify the pain points of your buyers. This way, you’ll know who you’re speaking to, and it will be easier to match your bot’s name to the visitor’s preferences. A good rule of thumb is not to make the name scary or name it by something that the potential client could have bad associations with. You should also make sure that the name is not vulgar in any way and does not touch on sensitive subjects, such as politics, religious beliefs, etc. Make it fit your brand and make it helpful instead of giving visitors a bad taste that might stick long-term.

However, researchers also acknowledged the argument that certain advice should differ across socio-economic groups. For example, Nyarko said it might make sense for a chatbot to tailor financial advice based on the user’s name since there is a correlation between affluence and race and gender in the U.S. It’s crucial to keep in mind that your chatbot name should ideally mirror your business’s identity when using one for brand messaging. A healthcare chatbot may be used for a variety of tasks, including gathering patient data, reminding users of upcoming appointments, determining symptoms, and more. In fact, one of the brand communications channels with the greatest growth is chatbots. If the COVID-19 epidemic has taught us anything over the past two years, it is that chatbots are an essential communication tool for companies in all sectors.

Frankenstein Reanimated explores the monstrous products of our ‘advanced’ technological moment through the lens of contemporary art practice. Join co-editor, Marc Garrett, for an introduction to the book. This will be followed by a series of provocations from artists Mary Flanagan and Anna Dumitriu, both of whom feature in the book, and an audience Q+A moderated by Ruth Catlow.

“This collection shines a light on artists as critically engaged citizens providing a kaleidoscopic view on our unevenly distributed future. These are the Frankensteins we need!” –

Felix Stalder,

Professor of Digital Culture, Zurich University of the Arts

Order advance copies of the book here.

Mary Shelley’s classic gothic horror and science fiction novel, Frankenstein, has inspired millions since it was published in 1818. Today, we are witness to many different horrors and phantoms of our own creation. Chronic wealth and health inequalities, climate change, democratic collapse, and the spectre of nuclear apocalypse are among the diffuse, monstrous products of our “advanced” technological moment.

Frankenstein Reanimated: Creation & Technology in the 21st Century, edited by Marc Garrett and Yiannis Colakides, retraces and contextualises three international art exhibitions exploring themes within Frankenstein, and speculates on what Mary Shelley would think about the world today. The book offers a lens through which to look at our current situation, and how art practices shape, and are shaped by, contemporary society.

Frankenstein Reanimated presents a dynamic collection of artworks, essays, and conversations, addressing: surveillance, biohacking, viruses, colonialism, digital culture, and more with leading thinkers, artists and technologists, including: Alexia Achilleos, Zach Blas, Frances A. Chiu, Ami Clarke, Régine Debatty, Mary Flanagan, Carla Gannis, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Srecko Horvat, Salvatore Iaconesi, Olga Kopenkina, Marinos Koutsomichalis, Shu Lea Cheang, Gretta Louw, Joana Moll, Laura Netz, Eryk Salvaggio, Devon Schiller, Guido Segni, Gregory Sholette, Karolina Sobecka, Alan Sondheim, Michael Szpakowski, Eugenio Tisselli, Ruben Verwaal, Paul Vanouse.

Frankenstein Reanimated includes full-colour illustrations and is designed by Mark Simmonds. The book follows Furtherfield and Torque Editions previous collaborative publication Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain.

Marc Garrett

Dr Marc Garrett explores postdigital contexts as part of an intersectional enquiry. An artist, curator and researcher he co-founded Furtherfield and has curated over 50 contemporary media arts exhibitions and projects nationally and internationally. He has written many critical and cultural essays, articles, interviews, and contributed to books about art, technology and social change. He is co-editor of Artists Re:thinking Games and Artists Re:thinking the Blockchain.

Mary Flanagan

Mary Flanagan has a research-based practice that investigates and exploits the seams between technology, play, and human experience, exploring how data, computing practices, errors / glitches, and games reflect human psychology and the limitations of knowledge. Flanagan has exhibited internationally at venues such as The Guggenheim, the Whitney, Tate Britain, and cultural centres in Spain, Portugal, Germany, France, Cyprus, China, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and more.

Anna Dumitriu

Anna Dumitriu is an award-winning, internationally renowned British artist who works with BioArt, sculpture, installation, and digital media to explore our relationship to microbiology, synthetic biology, and emerging technologies. Exhibitions include ZKM, Ars Electronica, Künstlerhaus Wein, BOZAR, Picasso Museum, HeK Basel, MOCA Taipei, LABoral, and the 6th Guangzhou Triennial.

Ruth Catlow

Ruth Catlow is a recovering web utopian. An artist, curator and researcher of emancipatory network cultures, practices and poetics, she is co-founding co-director of Furtherfield, and co-editor of Artists Re:thinking the Blockchain (2017) and Radical Friends – Decentralised Autonomous Organisations and the Arts.

Frankenstein Reanimated follows a collaboration with exhibition partners LaBoral, Gijon (ES), Furtherfield, London (UK) and NeMe, Limassol (CY) and made possible through support of NeMe and Furtherfield.

We are building CultureStake, the world’s first collective cultural decision making app (using Quadratic Voting on the blockchain) because we want to enable all communities to choose the creative experiences they want to have in their own areas. The original idea was driven by an awareness that top down arts programming is increasingly problematic. We wanted to find a way to give more people more of a say in what art and culture gets produced in their neighbourhoods – and more opportunity to be the co-creators. In a nutshell, our mission is to put the public at the heart of public arts.

Communities

We want communities to explore and learn together what we all want to experience in our localities. For example how might a theatre audience cast a play differently or a park community curate a public art exhibition?

Cultural Organisations

We want deeper, richer and more open consultation with the communities cultural organisations work for. For example, how might a city council find out which new artwork should occupy a recently vacated public plinth. Or how might an arts organisation discover which artist on their shortlist should be next summer’s blockbuster?

For Everyone

We want a data commons that widens the conversation about how art is valued by different communities around the world. For example, how might our ideas about culture change if we can see what’s important to other people?

We are using Quadratic Voting because it takes us all from confusing numbers to nuanced feelings.

In QV voters receive a number of ‘vibe credits’ which they can allocate to different creative proposals to express their support. The quadratic function means that showing a strong preference comes at a credit cost. Or rather:

This means that QV is quite unlike any other voting process. Indeed, unlike a one person one vote system, in QV votes express not just what we care about but how much we care! This matters because one person one vote systems usually don’t present the reason why someone voted the way they did or how strongly they felt about it. Politics have taught us not to trust the way votes are interpreted. Voters’ intentions are often misrepresented and communities are polarised about the limited information. Whereas QV allows us to express the intensity of our convictions, giving each of us:

Plus we’ve designed CultureStake so vote organisers can weight the votes of those closest to the issues that matter. For example, in our use of CultureStake for the People’s Park Plinth, any votes cast inside Finsbury Park mean more overall. So those most affected get more of a say.

And we run all CultureStake votes on the blockchain because the blockchain is like a big indelible ledger. This means that a vote cannot be rigged and is always stored extra safely so what we can promise voters is that they can trust our system.

There are many ways to run a CultureStake vote. A theatre could develop an unfinished performance and ask communities to choose the next steps. An arts organisation might offer up a range of different events and invite communities to choose what they want to encounter. Either way, the voting system doesn’t rely on asking everyone to just pick their favourite, but rather explore their thoughts and feelings in relation to a set of questions. So the result is always knowing more about what communities think and feel. Plus, we never show what ranked 1st, 2nd, or 3rd, but rather what was selected and what thoughts and opinions drove people’s selections.

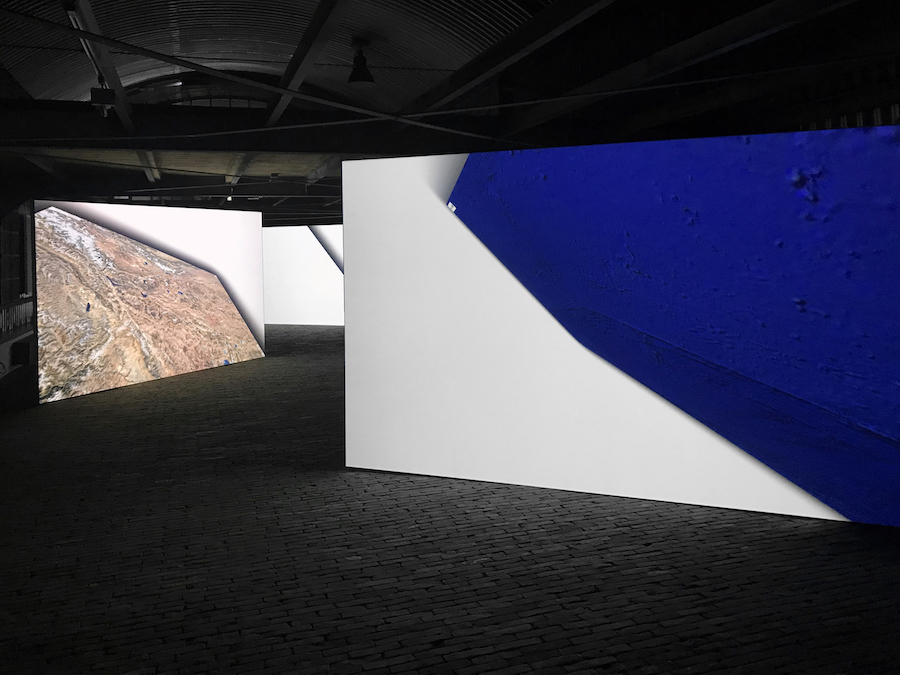

At Furtherfield we are using CultureStake to power our People’s Park Plinth initiative in Finsbury Park. The concept behind the People’s Park Plinth is that our Finsbury Park buildings and even the park itself will act as a plinth for public digital artworks chosen by our communities using our CultureStake app.

The Gallery building will therefore provide an interface where people can scan hoardings to access works which offer a range of XR-enabled experiences in the park. Annually there will be a set of ‘proposal’ artworks, which will give people a first glimpse at what can be created more fully later in the year. Everyone will have time to explore these proposals and then use CutlureStake to choose what they want.

In our pilot year we tripled local engagement and received amazing local feedback like this:

“I live nearby and I’ve been talking about this with my friends for months, it’s such a great idea, to give people a say!”

“[…]decentralisation allows people to have slower but more grassroots-based management of any decision making.”

“I think it’s good that we have a say as well. And I really love voting.”

“Usually I guess I choose art by going to a place and supporting it like that but I’ve never been involved so much in really deciding on what I will see next. And yeah it makes me actually feel good too.”

“[…] quite a lot of times actually […] art is reserved only for the higher echelons of society and I feel like this is really nice that anyone can come in and you vote for who you like or what art you like.”

“I do feel represented…”

We are now in the next phase of development and are actively looking for partners from different types of venues and communities to partner with us so we can explore their unique needs and ensure we have a robust system.

If you are a small, medium, large, networked, physical, touring, online or any other type of cultural entity that wants to deepen your community connections we would love to hear from you. We want to know how you would use CultureStake in your own context and what you would like to achieve. To find out more contact Charlotte and she’ll arrange a meet up.

A list of recommendations, reflecting the dynamic culture we are part of, straddling the fields of art, technology and social change.

Events, Exhibitions, Open Calls, Festivals and Conferences

Art was only a substitute for the Internet | The Wrong Biennial, has been dedicated exclusively to online art and that alone makes it very relevant. For this fifth edition, Andres Manniste has invited artists who he felt were convinced that the Internet and what it provides is an art and for whom networks are critical for the development of their thinking and their work. For many the Internet is a daily routine of checking social media, listening to podcasts or music and researching material. Every living artist aware of the unlimited resources provided by communications networks is influenced by the internet. Many have associated a major part of their art process with the internet. This exhibition is a place where art can be playful and challenging – https://bit.ly/3nMIZKJ

Angels & Discounts | Exhibition by Iris Pokovec | 3 – 26 November 2021 | Aksioma | Project Space, Ljubljana | Part of U30+ production programme for supporting young artists. Angels & Discounts is an ode to consumerism and an elegy to unfulfilled dreams and lost ideals. It talks about the love-hate attitude to consumerist and popular culture and glorifies its charm and its power of hypnotising the masses, while at the same time offering a reflection on the transience of society’s collective stream of thought. It is a narrative about the search for free choice in the numb somnolence of supermarket aisles and shelves with tinned peas and preserved compotes – https://bit.ly/2ZQlSHf

NFT Culture Proof | Launches 9 am 9 Nov 2021 | Nathaniel Stern, Scott Kildall and others | A participatory performance on the Blockchain – a completely on-chain collaborative text – a collective artwork and crypto-native NFT series. NFT Culture Proof is a 32-day Blockchain performance, where every participant continuously adds to a collaborative stream of live but immutable text, which will be permanently placed on-chain. Each day, there are “writing prompts” from artists, thinkers, and writers in the cryptoverse, which will both focus and drive the texts we produce. It is the first large-scale Blockchain work of its kind, making the public ledger an active stage for collective creativity. Every text block submitted generates a unique NFT for the participant. These will also live completely on-chain, as crypto-native SVGs – https://bit.ly/3bBLfyy

Lecture 5: The City: Laurie Anderson: Spending the War Without You | 10 Nov 2021 | Exploring the challenges we face as artists and citizens as we reinvent our culture with ambiguity and beauty. Laurie Anderson presents Spending the War Without You: Virtual Backgrounds. The City is the fifth in a series of six lectures, looking at the challenges we face as artists and citizens as we reinvent our culture with ambiguity and beauty. This talk will consider teachers, activism and politics. Presented by Laurie Anderson, one of America’s most renowned – and daring – creative pioneers. Known primarily for her multimedia presentations, she has cast herself in roles as varied as a visual artist, composer, poet, photographer, filmmaker, electronics whiz, vocalist, and instrumentalist. Event by Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard | Free event book at Eventbrite – https://bit.ly/3BvV9wd

Glitch: Aesthetic of the Pixels | Platform 101 – Vol.03 | Tehran, Iran | 5 – 12 Nov 2021 | Platform 101 is holding its third international group exhibition entitled “Glitch: Aesthetic of the Pixels”. After the great success of Vol.2, Platform 101, a nonprofit and independent art institution, is continuing the Glitch Video Art Group Exhibition in Tehran, Iran Vol.03, entitled “Glitch: Aesthetic of the Pixels”, curated by Mohammad Ali Famori, featuring 27 international glitch artists at Pejman Foundation: Kandovan – https://bit.ly/3pX2pPK

IAM Weekend | Barcelona Nov 11-13 2021 and Planet Earth: November 11-18, 2021 | Join the 7th annual gathering for mindful designers, researchers, strategists, artists, technologists, journalists and creative professionals looking to collectively envision sustainable futures for the internet(s). A week-long programme of live and pre-recorded sessions. The Planet Earth edition will feature live and pre-recorded sessions, available 24 hours across timezones, during 8 days, including the social live stream of Forum Day sessions of the Barcelona edition programme. Get access to the Planet Earth edition programme with a Week-long Pass or any Barcelona edition ticket. More info – https://bit.ly/3nVQwqr

Furtherfield at the Planet Earth Session at IAM Weekend | Nov 18th 2021 Watch live or on-demand the following pre-recorded videos: The Treaty of Finsbury Park 2025 – Interspecies Assembly (The one about biodiversity habitats) by Furtherfield + The New Design Congress + CreaTures. The Treaty of Finsbury Park 2025 – Ruth Catlow & Cade Diehm in conversation with Dr. Lara Houston. Get access to the Planet Earth edition programme with a Week-long Pass or any Barcelona edition ticket. More info – https://bit.ly/3nVQwqr

Call for Participation – Rendering Research | Deadline for submissions 14th Nov 2021 | We are seeking proposals to address how research is made public, and in this sense also to the infrastructures of research and its various systems of publishing. Organised by Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, in collaboration with Centre for the Study of the Networked Image, London South Bank University, Saint Luc École de recherche graphique in Brussels, and Transmediale festival for digital art & culture. APRJA is published by Aarhus University in partnership with Transmediale and hosted by the Royal Danish Library – https://bit.ly/3q0Na8w

People Like Us: Gone, Gone Beyond | Event by Barbican Centre | The Pit | 10 – 13 Nov 2021 | Watch and listen as unexpected narratives expand and unravel all at once around you. Inside this immersive, 360-degree cinematic installation, you’ll get to look far beyond the frame. Fragments of familiar and experimental films interact with song and audio clips in ever-changing, kaleidoscopic and kinetic collages. As time and space become elastic, viewers are opened to multiple meanings and perspectives by this seamless visual and surround-sound experience, with its playful and unsettling observations on popular culture. Under her artist name, People Like Us, Vicki Bennett has been evolving the field of audiovisual collage since the early 1990s, cutting up and layering found footage and archives | Tickets – https://bit.ly/3EqJX62

Tactical Entanglements: Creative AI Lab in conversation with Martin Zeilinger | 15 Nov 2021 6 pm FREE | Serpentine | TwitchOnline | A discussion panel on my book, “Tactical Entanglements: AI Art, Creative Agency, and the Limits of Intellectual Property” (meson press 2021). The event is put on by the Creative AI Lab and will be live-streamed on Twitch. Exploring issues around critical approaches to AI, digital art, and posthumanism with Mercedes Bunz and Daniel Chavez Heras (both Kings College London) and Eva Jäger (Serpentine Galleries). You can grab a free copy of Zeilinger’s book on the Meson Press publisher’s website, and a free e-reader with some additional relevant readings will be available on the Serpentine Galleries website – https://bit.ly/2Yqn6bk and https://meson.press/books/tactical-entanglements/

AI4FUTURE: OPEN CALL FOR RESIDENCIES | Deadline 15 NOV 2021 | AI4future is searching for 4 artists to work at an AI-based artwork in collaboration with young European activists to foster new urban community awareness. In recent years, Artificial Intelligence has been implemented in a number of fields functional to daily life: from those that simulate the cognitive abilities of the human being (image recognition, language automation, etc.) to the management of civil and social life (home automation, banking, self-driving vehicles, etc.) up to the economic and political organization (remote surveillance, privacy, impact on the world of work 4.0, health management, disinformation techniques, control over fundamental rights, etc.) – https://bit.ly/3bEeXTu

(re)programming: Strategies for Self-Renewal | With Eyal Weizman | 15 Nov 2021 7 pm | Aksioma | We have found ourselves at the crossroads of an existential decision: do we bring the mistakes of the enlightenment to their biological conclusion or do we develop a magical capacity to self-renew? For the 10th anniversary of Tactics & Practice, Aksioma presents (re)programming: Strategies for Self-Renewal “festival of conversations” with world-class thinkers debating key issues, from infrastructure and energy to community and AI, curated and conducted by writer and journalist Marta Peirano. The festival consists of 8 streaming events taking place every third Monday of the month throughout the year – https://bit.ly/3EDTA1n

Lorenzo Ravano: The Global South and the History of Political Thought | Online | 18 Nov 2021, 6 – 8 pm | The Critical Perspectives on Democratic Anti-Colonialism project invites you to our next Fall 2021 workshop. The program brings together faculty and students from across The New School interested in exploring the theoretical foundations and political manifestations of radical democratic and anti-colonial traditions. Ravano, Postdoctoral Fellow at Université Paris Nanterre, will be presenting his work, “The Global South and the History of Political Thought”. Anthony Bogues, Asa Messer Professor of Humanities and Critical Theory, Professor of Africana Studies and Director of the Center of the Study of Slavery and Justice at Brown University, will be commenting – https://bit.ly/3ECPVku

WhistleblowingForChange: Exposing Systems of Power & Injustice | The 25th Conference of the Disruption Network Lab | Conference and book launch | 26 – 28 Nov 2021. At Kunstquartier Bethanien – Berlin. The courageous acts of whistleblowing that inspired the world over the past few years have changed our perception of surveillance and control in today’s information society. But what are the wider effects of whistleblowing as an act of dissent on politics, society, and the arts? How does it contribute to new courses of action, digital tools, and content? This urgent intervention based on the work of Berlin’s Disruption Network Lab examines this growing phenomenon, offering interdisciplinary pathways to empower the public by investigating whistleblowing as a developing political practice that has the ability to provoke change from within | Facebook link – https://bit.ly/3o1ibXj

Unravelling Women’s Art | 25 November 6 pm – 7:30 pm | £5 | ONLINE EVENT | Join author PL Henderson and a trio of artists for an insightful discussion into what links female textile artists and the arts they produce, revealing a global and historic patchwork of assorted roles, identities and representations. Henderson’s new book, Unravelling Women’s Art: Creators, Rebels, & Innovators in Textile Arts (Aurora Metro Books) offers a unique overview of female-centric textile art production including embroidery, weaving, soft sculpture and more. Including over 20 interviews with contemporary textile artists, the books invites us into their practices, themes and personal motivation – https://bit.ly/3wxeqwr

Two Postdoc Positions in Critical Environmental Data Studies | Deadline 30 Nov 2021, Expected start 1 Mar 2022 | The Department of Digital Design and Information Studies within the School of Communication and Culture at Aarhus University (Denmark) invites applications for two postdoctoral positions in Critical Environmental Data Studies. The postdoc positions are affiliated with the research project Design and Aesthetics for Environmental Data funded by the Aarhus University Research Foundation (AUFF). The postdoc positions are full-time, two-year fixed-term positions. Design and Aesthetics for Environmental Data focus on historical and current practices of seeing, knowing, and designing the environment and the planet as data: as patterns, visualizations, projections, models, simulations, and other aesthetic objects with epistemic value. The working language of the project is English – https://bit.ly/3GGfu5P

Call for Book Chapters | Feminist Futures: From Witches to Maids to Robots and Beyond | Proposal submission deadline 15 Dec 2021 | Feminist Futures is a book all about bridges and connections! It aspires to take a look at the future, it wants to tell the story of witches, how neo-feudalism relates to the present monsters, how postcolonialism and post cold war politics brought us here when it comes to women’s rights. It is about automation and the constant repetition of the need for care without really doing it. It wants to bring these stories at the centre stage to talk about the future, to shed light on research that can lead us to what unites us and not to what divides us – https://bit.ly/3nSUsZ4

Books, Papers & Publications

Artistic Research – Dead on Arrival? Research practices of self-organized collectives versus managerial visions of artistic research | By Florian Cramer. (First published in Henk Slager [ed.], The Postresearch Condition, Utrecht: Metropolis M Books, 2021, p. 19-25). Since at least the early 20th century, artists groups have called their work “research”. Canonized examples include the “Bureau des recherches surréalistes” (“Bureau of Surrealist Research”) founded in Paris by André Breton and fellow Surrealists in 1925 and the Situationist International which, from 1957 to 1972, operated under the moniker of a research group and whose periodical had the form of a research journal. […] Today, transdisciplinary art/research collectives seem to be more common as a contemporary art practice in non-Western regions than in Western countries where art systems are more institutionalized – https://bit.ly/2ZNpjy1

Machines We Trust: Perspectives on Dependable AI | Edited by Marcello Pelillo and Teresa Scantamburlo | Experts from disciplines that range from computer science to philosophy consider the challenges of building AI systems that humans can trust. Artificial intelligence-based algorithms now marshal an astonishing range of our daily activities, from driving a car (“turn left in 400 yards”) to making a purchase (“products recommended for you”). How can we design AI technologies that humans can trust, especially in such areas of application as law enforcement and the recruitment and hiring process? In this volume, experts from a range of disciplines discuss the ethical and social implications of the proliferation of AI systems, considering bias, transparency, and other issues – https://bit.ly/3AMedWR

The Art of Activism: Your all-purpose guide to Making the Impossible Possible | By Steve Duncombe and Steve Lambert | It brings together the authors’ extensive practical knowledge—gleaned from over a decade’s experience training activists around the world—with theoretical insights from fields as far-ranging as cultural studies and cognitive science. From the United Farm Workers’ boycott movement in sixties’ California to a canal-side beach in present-day Saint Petersburg, these pages are packed with contemporary and historical case studies that have been shown to work in practice. The accompanying workbook contains fifty expertly crafted exercises to help you flex your creative imagination and hone your political tactics, taking you step-by-step toward becoming the most persuasive and impactful artistic activist you can possibly be – https://bit.ly/3CcKCr9

Whistleblowing for Change: Exposing Systems of Power & Injustice | Editor Tatiana Bazzichelli | Out 27 Nov 2021 | The courageous acts of whistleblowing that inspired the world over the past few years have changed our perception of surveillance and control in today’s information society. But what are the wider effects of whistleblowing as an act of dissent on politics, society, and the arts? How does it contribute to new courses of action, digital tools, and contexts? This urgent intervention based on the work of Berlin’s Disruption Network Lab examines this growing phenomenon, offering interdisciplinary pathways to empower the public by investigating whistleblowing as a developing political practice that has the ability to provoke change from within – https://bit.ly/3nTyZiP

Proof of Work: Blockchain Provocations 2011–2021 | By Rhea Myers | Art Editions, Forthcoming Jun 2022 | DAO? BTC? NFT? ETH? ART? WTF? HODL as OG crypto artist, writer, and hacker Rhea Myers searches for faces in cryptographic hashes, follows a day in the life of a young shibe in the year 2032, and patiently explains why all art should be destructively uploaded to the blockchain. Now an acknowledged pioneer whose work has graced the auction room at Sotheby’s, Myers embarked on her first art projects focusing on blockchain tech in 2011, making her one of the first artists to engage in creative, speculative and conceptual engagements with ‘the new internet’. This anthology brings together annotated presentations of Myers’s blockchain artworks along with her essays, critiques, reviews, and fictions—a sustained critical encounter between the cultures and histories of the art world and crypto-utopianism, technically accomplished but always generously demystifying and often mischievous – https://bit.ly/3nSpmki

Critical Theory and New Materialisms | Edited By Hartmut Rosa, Christoph Henning, Arthur Bueno | Published by Routledge, 15 June 2021 | Bringing together authors from two intellectual traditions that have, so far, generally developed independently of one another – critical theory and new materialism – this book addresses the fundamental differences and potential connections that exist between these two schools of thought. With a focus on some of the most pressing questions of contemporary philosophy and social theory – in particular, those concerning the status of long-standing and contested separations between matter and life, the biological and the symbolic, passivity and agency, affectivity and rationality – it shows that recent developments in both traditions point to important convergences between them and thus prepare the ground for a more direct confrontation and cross-fertilization – https://bit.ly/3BHvIrv

Articles, Interviews, Blogs, Presentations, Videos

The Chaos of Eros: in conversation with the programmers of Erotic Awakenings | Maria Isabel Martinez | Erotic life is a treasure we hold close until we believe its delight might multiply in the hands, eyes, ears, or mouth of another. One such place for sharing is “Erotic Awakenings,” an archive primarily containing writings hosted on the website of Toronto artist-run gallery Hearth Garage. The project is a collaboration between the gallery’s programmers Benjamin de Boer, Philip Ocampo, Rowan Lynch, and Sameen Mahboubi and writer and facilitator Fan Wu. Each piece of writing is singular in form and content, reflective of our varied erotic experiences. In an erotic moment, we might become unfastened from a solid sense of our identity, or further reminded of the body we can’t escape – https://bit.ly/3GPuONB

Artgames and interspecies LARPS with Marc and Ruth of Furtherfield | Podcast | The ReImagining Value Action Lab | “We talked about art, games, LARPs and other subversive high jinks on the latest episode of our Conspiracies and Countergames podcast.” Furtherfield disrupts and democratises art and technology through exhibitions, labs & debates, for deep exploration, open tools & free-thinking and is London’s longest-running (de)centre for art and technology whose mission is to disrupt and democratise through deep exploration, open tools and free-thinking. The ReImagining Value Action Lab (RiVAL) is a research and creativity workshop for the radical imagination active around the world and locally in Thunder Bay, Canada – https://bit.ly/3k815pn

The Digital Art Conundrum – how to evaluate digital art? | Computational Aesthetics | By Josephine Bosma | Digital devices have been part of developments in culture and society for decades, the arts included. They influenced, inspired, or even ‘co-produced’ the work of artists in performance, sculpture, robotics, sound art, and more. […] Though accurate and precise, it is not easily understandable and is a quite theoretical approach. To simplify their proposal: computational aesthetics offers a much-needed alternative to ‘traditional’ definitions of digital art as a purely technological or visual art form. It offers a broader perspective on the field – https://bit.ly/3BEKSy3

London’s ‘Square Mile’ Is One Big Monument To Slavery | By Stewart Home | ArtReview | When it comes to addressing what to do with artworks and memorials connected to historic racism and attendant issues relating to colonialism, some talk up their commitment to change, but their lack of action exposes a preference for the status quo. The City of London Corporation is the local authority that covers the capital’s international financial district. Not only does the Corporation pack more problematic memorials into its famous ‘Square Mile’ than almost any other council in the UK (or, for that matter, the world), it is simultaneously a major patron of the arts.” – https://bit.ly/3nJBm7y

Atari-style Artwork Makes the ‘Guinness World Records 2022’ Book | Dartmouth Edu | Mary Flanagan shows how games can be collaborative through a giant Atari 2600 joystick. “Space Invaders.” “Asteroids.” “Pac-Man.” In the 1980s, the Atari 2600 revolutionized the video game industry as families revelled in the novelty of playing video games on the TV at home. When she was growing up, professor, game designer, and artist Mary Flanagan says the Atari 2600 was one of her most influential digital experiences. Years later, Flanagan’s tribute to that experience, [giantJoystick], made it into the Guinness World Records 2022 as the largest joystick in the world – https://bit.ly/3pYupSZ

AI Horror Movie Wins Lumen Gold | The Lumen Prize for Art and Technology awarded its coveted Gold Award with a cash prize of US$4,000 to UK artist Nye Thompson and UBERMORGEN for UNINVITED, the world’s first horror movie for and by machines. UNINVITED is a horror film for machine networks and human-machine organisms exploring the nature of perception and realism of the unknown and the terror of angst and exhaustion within emergent network consciousness. This generative work (2018–) is a self-evolving networked organism watching and generating a recursive ‘horror film’ scenario using mechatronic Monsters – digital flesh running machine learning algorithms. The work is described by the artists as a radically new creature looking at the world, hearing the universe through millions of hallucinogenic virally-abused sensors and creating a hybrid nervous system – https://bit.ly/3CzRI98

‘It’s a game-changer for us’: Artists welcome guaranteed basic income plan | Deirdre Falvey | Irish Times | The pilot for a new basic income guarantee scheme for artists and arts workers could see “around 2,000” creative workers drawing income from March 2022, or “the beginning of April, and no later than that”, said Minister for the Arts Catherine Martin. She gave details of the pilot project, which will be backed by €25 million funding in 2022, at Wednesday’s Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media budget briefing. A basic income guarantee was the top recommendation of the Arts and Culture Recovery Taskforce’s Life Worth Living report in November 2020, and the Minister said she intends to follow it “as closely as possible and to deliver a scheme that benefits artists and creative arts workers”. The three-year pilot will involve a weekly payment of €325 a week. The department later confirmed there will be no means test to take part in the scheme – https://bit.ly/2ZP73V6

Rhythm and Geometry: Constructivist Art in Britain since 1951 | Review by Bbronaċ Ferran | Studio International | An exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre captures something of the mood of the present, in its reflection on a balancing of constraint and liberation. Conceived by Tania Moore, the Joyce and Michael Morris chief curator, the exhibition draws closely on a “substantial bequest” in 2019 from husband and wife Joyce and Michael Morris, who developed a unique collection of British constructivist art from the 1950s on. As the couple were acquainted with many of the artists included, their collection was informed by their personal taste and sensibility. Its acquisition by the Sainsbury Centre opens up opportunities for new research from a historical perspective into a significantly under-studied domain of postwar practice – https://bit.ly/3q5huP3

These Companies Are Already Living in Zuckerberg’s Metaverse | By Megan Carnegie | Wired/Business | The Meta dream envisages whole companies operating in a virtual world. Many made the switch years ago—with mixed results. Facebook’s metaverse, or Meta’s metaverse, isn’t just being touted as a better version of the internet—it’s being hailed as a better version of reality. […] This space, Zuckerberg claims, won’t be created by one single company, but rather by a network of creators and developers. First problem: 91% of software developers are male. Second problem: You’ve been living in a version of metaverse for years—and, having taken over video games, it’s now coming for the world of work – https://bit.ly/3bwLNWn

Crofton Black – How does the world work? | Exposing the Invisible | Podcast | Crofton Black ended up as an investigator almost by chance. With a background in English Literature and Medieval and Renaissance philosophy, he took an unexpected turn into investigating secret prisons and extraordinary renditions. He is a writer and investigator. He is co-author of Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition and CIA Torture Unredacted, and works on technology and security topics for The Bureau of Investigative Journalism in London. Before this he was a history of philosophy academic, specialising in theories of knowledge and interpretation. He has a PhD from the Warburg Institute, London and was a Humboldt Fellow at the Freie Universität Berlin – https://bit.ly/2ZIT1nO

Kirill Medvedev in prison (Moscow, Russia) | An international well known muscovite poet, translator, publicist, activist and community organizer, co-founder of Arkadiy Kots combat-folk band, a long term Free Home learner, has been arrested along with other activists. They were defending a courtyard adjacent to Sretenka street from oligarch Deripaska’s development of an unlawful construction, a luxury apartment hotel rising right on the site of historic buildings from the 18th century – despite the protests of the local residents the activists were aggressively attacked by the police and kept in the police station for 24 hours awaiting the court hearing. As the excavation continues, they are imprisoned at spetspriyomnik nr-r. 1 and 2 already for 5 days. Since long Kirill is engaged in the defence of peoples land and territories defence, against extractivism, real estate development and criminal waste dumps – https://bit.ly/3mw3uvA

Image: Hydar Dewachi. Image Courtesy of Furtherfield. View from the People’s Park Plinth Voting Weekend (14 -15 August 2021), Furtherfield Gallery, Finsbury Park.

The FurtherList Archives

https://www.furtherfield.org/the-furtherlist-archives/

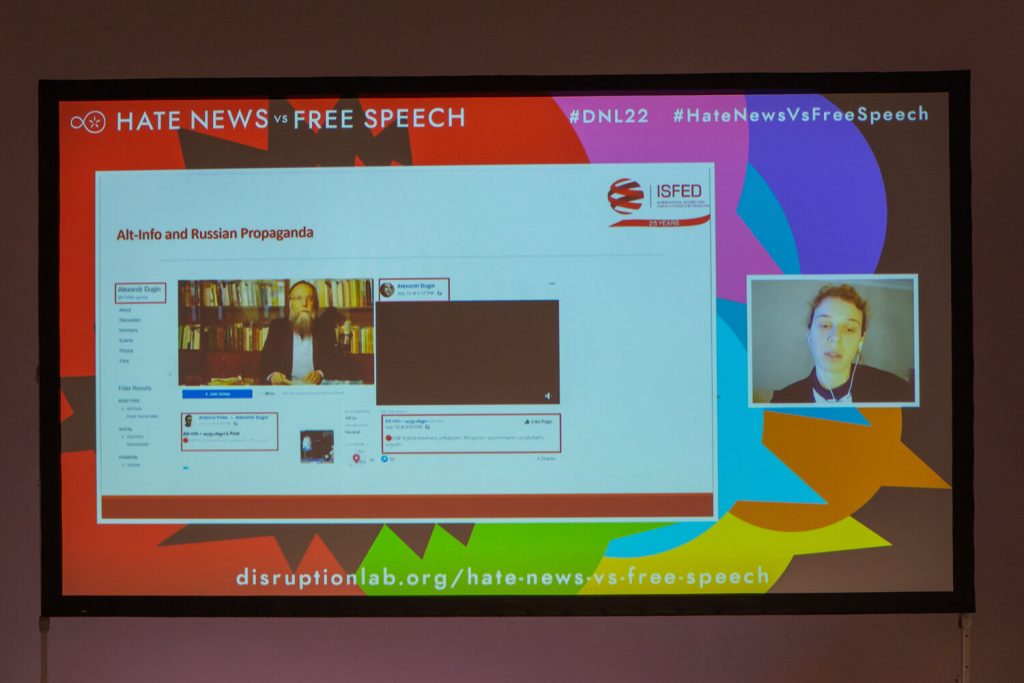

The 22nd conference of the Disruption Network Lab, “HATE NEWS vs. FREE SPEECH”, explored polarization and pluralism in Georgian media, opening on 12 December 2020 in partnership with the Regional Democratic Hub – Caucasus.

Introduced by Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger, the Programme and Community Director of the Disruption Network Lab, the two-day-event brought together journalists, activists and experts from based in Georgia and Germany to look into the manifestations as well as the consequences of information manipulation and deliberate hate speech within the Georgian media landscape.

The conference, held at Kunstquartier Bethanien in Berlin as a combination of online and on-site formats, investigated a hyper-polarised system, in which exploitative manipulation of facts and orchestrated attempts to mislead people through delivering false information are dangerously eroding media independence, pluralism and freedom of speech. In the context of deliberate technology-fuelled disinformation, spread by news outlets of religious and political influence, hostile countries and other malign sources, the work of independent Georgian journalists is often delegitimised by public authorities and denigrated in a wave of generalisations against media objectivity, to undermine independent information and stifle criticism.

As Bazzichelli stressed in her introductory statement, independent journalists reporting on information that is in the public interest are targeted because of the role they play in ensuring an informed society. At the same time, a global process of mystification is progressively blurring the boundary between what is false and what is real, growing to such a level that traditional media seems incapable of protecting society from a tide of disinformation, and becomes part of the problem.

Opening the first panel, “Polarization and Media Ethics in Georgia”, the moderator Maya Talakhadze, Co-Founder of the Regional Democratic Hub – Caucasus explained that, similar to other former Soviet Union countries, the political environment in Georgia has been polarized since the independence of the country. This has led to highly partisan media and to a marked divergence of political attitudes to ideological extremes within the around 3.7 million Georgians. Although the widespread of the internet guaranteed access to new media outlets and social media opened the way to a more pluralistic media environment, Georgian society soon faced the new challenges of widespread online disinformation, ethics violations and hate speech.

Professor Tamar Kintsurashvili, Executive Director of the Media Development Foundation and Associate Professor at Ilia State University, referred to Georgia as the country with the most pluralistic and free media environment in South Caucasus region. Nevertheless, according to Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders, its information system appears weaker and weaker, public broadcasters have been accused of favouring the government and lawmakers have repeatedly attempted to restrict freedom of expression.

Professor Kintsurashvili stressed how such an environment cannot be considered independent and negatively contributes to the polarization of the country. In her critical analysis, Georgian media pluralism could be described as the product of competing political interests, rather than a sign of strong freedom of expression and an independent press in the country. Despite this, Georgian civil society is widely praised for its diversity and strength.

In Georgia, most media have a political affiliation and align themselves with the agenda of a candidate or a party. This results in the actual instrumentalization of mainstream media and the concentration of ownership of TV stations, online media outlets and newspapers in the hands of the dominant political parties, which are shaping the overall media environment.

Professor Kintsurashvili recalled that in 2017 the ownership of pro-opposition Georgian TV channel Rustavi 2 was transferred to the businessman Kibar Khalvashi, its previous owner, after a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). The case is instructive of the complexity of the Georgian media landscape. Khalvashi’s opponents accused him of having close ties to the government and warned that the new ownership could not guarantee freedom of expression and independence for journalists and broadcasts. Following the ECHR ruling, two new opposition broadcasters emerged.

Professor Kintsurashvili highlighted that, to come to a full understanding of the country, one must consider the possible sympathies of the Georgian politicians toward the Russian Federation, despite the 2008 war and its continuous interferences in domestic affairs.

Many critical voices and independent investigations observe that Russia is supporting a galaxy of media outlets active all over the Caucasus, characterised by a lack of transparency and accountability. These actors promote anti-Western propaganda and are partially responsible for the radicalisation and antagonization of the Georgian society, leveraged to disrupt social cohesion and push the country away from the EU’s Eastern Partnership with the six countries of its Eastern neighbourhood –Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine.

Professor Kintsurashvili points out that while outlets such as Sputnik or Russia Today are openly funded by the Russian government or by Russian oligarchs, the ownership structures of dozens of online platforms remain unclear, and many vanish after a few weeks of activity.

In addition to this, the panellist considered that economic resources for independent media are limited and a lack of transparency of financing – especially in online media – which poses a serious problem for the independence and impartiality of many media outlets, as they are not accountable to the Georgian public but to their owners. Neutral newsrooms with no political affiliation are not self-sufficient and manage to have a small impact on the overall environment; nothing compared to big TV channels, which remain the major source of information in the country.

Taking a step from such a polarized environment shaped by domestic and foreign actors with a political agenda, the second panellist Nata Dzvelishvili, Executive Director at Indigo Publishing, focused on the current state of media ethics in Georgia and the lack of media literacy among Georgians. She considered that, in such a polluted disinformation ecosystem, the majority have almost no reliable instruments to orientate and discern good independent journalism, fake news and poor-quality reporting, which means also that the capability to identify verifiable information in the public interest, and information that does not meet precise ethical standards, is limited.

Dzvelishvili is the former Executive Director of the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics, the self-regulatory body of media in Georgia. She pointed out that by decoding the authenticity of online news we can see how, alongside with the so-called fake news, there is also an alarming degree of laxity and journalistic errors arising from poor research and superficial verification. She listed a few frequent unethical behaviours and violations, from the lack of accuracy to unprofessional coverage of facts reported to arouse curiosity or broad interest through the inclusion of exaggerated or lurid details. In Georgia, this last aspect is mirrored in an unfair and hyper-partisan selection of facts, too.

The Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics – a body composed of 400 member journalists, which processes complaints and makes decisions on issues regarding ethical standards and principles – warned that Georgian media too often spread news based on unverified facts, or even simple errors, generating misinformation. Bad information undermines the credibility of media, and unprofessional journalism opens the way for widespread disinformation and misinformation.

Dzvelishvili explained that in Georgia the most critical topics subject to manipulation due to political interest are those related to religious sentiment, LGBTQI identities, migration and nationalism. In her intervention she presented examples of campaigns fuelling homophobia, racism and reopening historic traumas, fruitful ground for the growth of ultra-nationalistic, conservative, and pro-Russian narratives.

Many of the media outlets accused of spreading anti-Western and pro-Russian propaganda acted all over the Caucasus to disseminate disinformation about Georgia’s position on the Karabakh conflict, and thus foster hostility between ethnic Armenian, Azerbaijani and Georgian populations. Rumours and fully fabricated stories about Georgian Muslims ready to gain independence led to the concrete risk of a conflict between ethnic Georgians, the religious orthodox and Muslims, and represented a new pretext to call for Russian intervention to resolve the conflict. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic was used to fuel anti-Western feelings, provoke mistrust in science, discredit Western democracies and divide the country.

Nini Gvilia, Project Assistant for Social Media Monitoring at the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED), focused on social media in Georgia, which – she explained – 20 percent of the population use as their main source of information. Political activities have strongly shifted to Facebook and other social media, with the support of agencies such as The Marketing Heaven, which enables a more pluralised information environment but also sharpens the risk of misuse by malign actors.

News Front, a Georgian-language website, is one of these. Facts can be irrelevant against a torrent of abuse and hatred towards journalists and opponents, made possible by algorithms, fake accounts, coordinated bots and trolls, that generate viral postings on social media. News Front has also been active on Facebook since 2019. Analysing the interactions of its audience, it is observable that manipulation also arises by weaponizing memes to propel hate speech and denigration or creating false campaigns to distract public attention from actual news. Marginal voices and fake news can be disseminated by inflating the number of shares with automated or semi-automated accounts, which manipulate public opinion by boosting the popularity of online posts and amplifying rumours.

Many Georgians are still anchored to very traditionalist and conservative beliefs. Groups of right-wing extremists offer appealing online spaces filled with redundant rhetoric, gossip columns, sport blogs, and other apparently harmless content, which actually underpins anti-liberal, misogynistic, racist and homophobic views, pushing for a new authoritarian turnaround. Too often, mainstream TV channels and newspapers pick up staged news from such a disinformation ecosystem, enforcing a revisionist narrative built on manipulated facts and fake interactions, arrogance and violence.

Eka Rostomashvili, Advocacy and Campaigns Coordinator at Transparency International, moderated the panel “Misinformation on Social Media during Elections”. The opening contribution by Varoon Bashyakarla, Data Scientist at Tactical Tech’s Data & Politics Project, focused on how the ‘digital influence industry’operates. In addition, Bashyakarla dissected some of the dynamics that allow personal data to be weaponised for political purposes.

As he recalled, personal data of potential electors is being used constantly for political purposes – even without a precise agenda, just to spread disinformation. Hundreds of companies around the world profile people to influence and predict their political choices. Working with journalists, academics, and civil society organisations, Bashyakarla underlined how these tech firms exploit personal information as a political asset and source of political intelligence.

Many countries traditionally hold voter rolls containing basic information of their electors. Voters’ data is at the heart of modern campaigning and many of the companies working in consumers tech have opened new divisions dedicated to political technology – a term commonly used in the former Soviet states for a highly developed industry of political manipulation – to build statistical models that spy on voters to learn from their preferences and characteristics. Cambridge Analytica was just one of the many entities collecting and misusing intimate personal data to target and manipulate the electorate.

Last year, personally identifiable information of 4.9 million Georgians from 2011 appeared online. Many suspected that the leak was triggered to undermine voters’ faith in elections. However, a leak consisting of 200 million US-American voter files, with personal data including ethnicity and religion, had already demonstrated in 2017 – illustrating how risky election tech can be. The same happened in the Philippines, where the website of the government was subject to a cyber-attack and 340 gigabytes of the personal details of 55 million voters appeared online, and in Turkey, where in 2016 a leak of a 6.6 gigabyte file made available information of 50 million voters.

Bashyakarla discussed then how the extraction of value from political data works and explained the logic behind A/B testing, deployed to compare the performance of two competing advertisements. He warned that societies around the world are exposed to an unprecedented volume of testing. During the last US elections, for example, on the day of the third presidential debate a single online content could be shared in up to 175,000 different variations to test the reaction of the electorate.

Politicians test their postings, images, headlines and slogans to learn in which areas voters are more sympathetic to their messages; what causes in different regions of the country they care more about; and what topics are more likely to be appreciated by a specific audience. As Facebook suggests in one of its advertisements, these techniques allow you to “find the perfect match between your ad and your audience.”

In Georgia, the volume of unsolicited texting and even phone calls spreading political messages that electors receive before elections is overwhelming. Both pro-government political parties and opposition parties deploy similar tactics, which reach their peak point during elections. Coinciding with this very intense activity, the number of online pages spreading fake news triples, with hatred campaigns amplifying differences and fuelling polarization.

Mikheil Benidze, Chief of Party for the new Georgia Information Integrity Program at the Zinc Network, shared his observations on how social media platforms have been weaponized for electoral purposes and how Georgian civil society has risen to the challenge. In the next few years, the Georgia Information Integrity Program, run by the Zinc Network, is going to look into the activities of online users, to research why certain narratives are successful and what their actual impact is.

Benidze recalled that the web is full of traps, like fake news websites that look like the online version of mainstream newspapers, and TV channels, which deceive readers. These fake websites are used to co-ordinate campaigns and networks of political influence, propagate nationalistic, xenophobic, and homophobic content and to undermine the development of a multicultural liberal democracy. The panellist considered that algorithms amplify those messages even more, and praised Georgian civil society organisations for constantly debunking, exposing and analysing facts to protect a free, democratic and open debate. People get spontaneously together and mobilise to strengthen independent fact-checking initiatives and encourage the co-operation with social networks to monitor and delate online harmful content.

The panel was concluded by the contribution of Rafael Goldzweig, Research Coordinator at Democracy Reporting International, an independent non-profit organisation based in Berlin, which promotes political participation of citizens, accountability of state bodies and the development of democratic institutions worldwide. Goldzweig compared the trends observed in Georgia described throughout the first day of the conference with what happens in other countries. He offered an overview of regulatory approaches and initiatives – particularly those debated in the European Union – for making the online environment more resilient against disinformation, hate speech and other challenges.

The digital sphere and its interactions proved to be able to determine the course of elections and host activities, which can undermine the stability of a fragile institutional system. The researcher pointed out that, all over the world, social media has become subject to electoral observation, too, to monitor the rights of candidates and of the electorate.

Goldzweig is confident that more organisations and actors around the world can replicate the monitoring activities of Democracy Reporting International. He suggested that transparency and monitoring are fundamental to understand what happens online, and that we are facing a multi-stakeholder responsibility, since tech companies are asked to provide solutions and governments to maintain a central role. These actors must facilitate the monitoring by civil society and implement tech that enforces community standards able to guarantee individual and collective rights.

The first day’s guests presented a clearer image of the complex situation in the Georgian media landscape, in which disinformation and propaganda seek to animate people into becoming conduits of divisive messages and violence. All panellists expressed concern about the alarming levels of homophobia and xenophobia. Several contributions suggested that journalistic self-regulation and a respect for precise ethical principles appear to be the only way to guarantee strong and free information systems, keeping in mind that Georgian democratic institutions are still fragile and that lawmakers will try to implement new regulations as a leverage to limit freedom of expressions.