Art, to misparaphrase Jeff Koons, reflects the ego of its audience. It flatters their ideological investments and symbolically resolves their contradictions. Literature’s readers and art’s viewers change over time, bringing different ways of reading and seeing to bear. This relationship is not static or one-way. The ideal audience member addressed by art at any given moment is as much produced by art as a producer of it. Those works that find lasting audiences influence other works and enter the canon. But as audiences change the way that the canon is constructed changes. And vice versa.

“The Digital Humanities” is the contemporary rebranding of humanities computing. Humanities for the age of Google rather than the East India Company.

Its currency is the statistical analysis of texts, images and other cultural resources individually or in aggregate (through “distant reading” and “cultural analytics“).

In the Digital Humanities, texts and images are read and viewed using computer algorithms. They are “read” and “viewed” by algorithms, which then act on what they perceive. Often in great number, thousands or millions of images or pages of text at a time, many more than a human being can consider at once.

The limitations of these approaches are obvious, but they provide a refreshing formal view of art that can support or challenge the imaginary lifeworld of Theory. They are also more realistic as a contemporary basis for the training of the administrative class, which was a historical social function of the humanities.

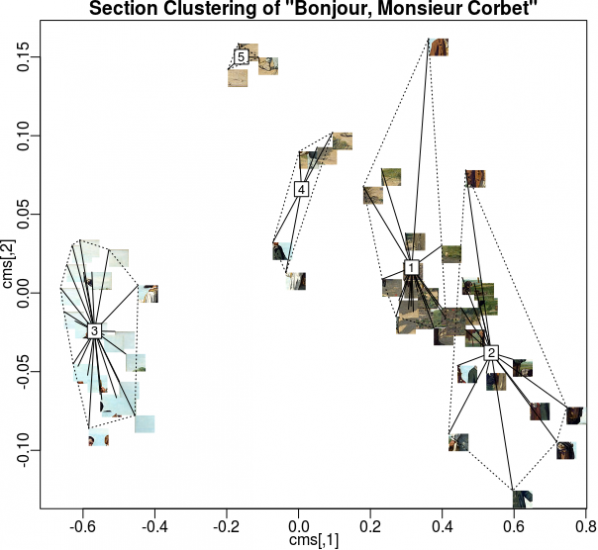

Digital Humanities algorithms are designed to find and report particular features of texts and images that are of interest to their operators. The most repeated words and names, the locations and valences of subjects, topics and faces and colours. They produce quantitative statistics regarding works as a whole or about populations of works rather than qualitiative reflection on the context of a work. Whether producing a numeric rating or score, or arranging words or images in clouds, the algorithms have the first and most complete view of the cultural works in any given Digital Humanities project.

This means that algorithms are the paradigmatic audience of art in the Digital Humanities.

Imagine an art that reflects their ego, or at least that addresses them directly.

Appealing to their attention directly is a form of creativity related to Search Engine Optimization (SEO) or spam generation. This could be done using randomly generated nonsense words and images for many algorithms, but as with SEO and spam ultimately we want to reach their human users or customers. And many algorithms expect words from specific lists or real-world locations, or images with particular formal properties.

A satirical Markov Chain-generated text.

The commonest historical way of generating new texts and images from old is the Markov Chain, a simple statistical model of an existing work. Their output becomes nonsensical over time but this is not an issue in texts intended to be read by algorithms – they are not looking for global sense in the way that human readers are. The unpredictable output of such methods is however an issue as we are trying to structure new works to appeal to algorithms rather than superficially resemble old works as evaluated by a human reader.

The two kinds of analysis commonly performed on cultural works in the Digital Humanities require different statistical approaches. Single-work analyses include word counts, entropy measures and other measures that can be performed without reference to a corpus. Corpus analysis requires many works for comparison and includes methods such as tf-idf, k-means clustering, topic modeling and finding property ranges or averages.

ugly despairs racist data lunatic digital computing digital digital humanities digital victim furious horrific research text racism loathe computing text humanities betrayed digital text humanities whitewash computing computing cheaters brainwashing digital research university university research falsifypo pseudoscience research university worry research data technology computing humanities technology data technology research university research university computing greenwasher cruel computing university data disastrous research digital guilt technology university sinful loss victimized computing humiliated humanities university research ranter text text technology digital computing despair text technology data irritate humanities text data technology university heartbreaking digital humanities text chastising text hysteria text digital research destructive technology data anger technology murderous data computing idiotic humanities terror destroys data withdrawal liars university technology betrays loathed despondent data humanities

A text that will apear critical of the Digital Humanities to an algorithm,

created using negative AFINN words & words from Wikipedia’s “Digital Humanities” article

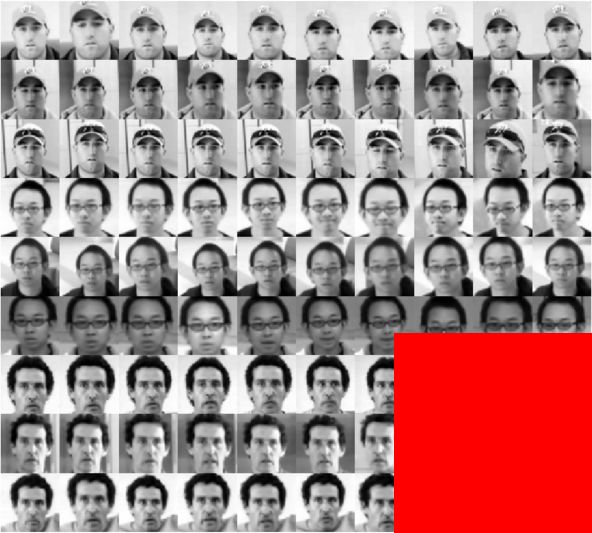

We can use our knowledge of these algorithms and of common training datasets such as the word valence list AFINN and the Yale Face Database, along with existing corpuses such as flickr, Wikipedia or Project Gutenberg, to create individual works and series of works packed with features for them to detect.

web isbn hurrah superb breathtaking hurrah outstanding superb breathtaking isbn breathtaking isbn breathtaking thrilled web internet hurrah media web internet outstanding thrilled hurrah web thrilled media thrilled superb breathtaking art breathtaking media superb hurrah superb net artists outstanding internet outstanding net superb thrilled thrilled art hurrah based outstanding superb net internet artists web art art artists internet breathtaking based net hurrah outstanding thrilled superb hurrah media based outstanding media art artists outstanding isbn based net based thrilled artists isbn breathtaking

A text that will appear supportive of Internet art to an algorithm,

made using positive AFINN words and words from Wikipedia’s “Internet Art” article.

When producing textual works for individual analysis, sentiment scores can be manufactured for terms associated with the works being read. Topics can be created by placing those terms in close proximity. Sentence lengths can be padded with stopwords that will not affect other analysis as they will be removed before it is performed. Named entities and geolocations can be associated, given sentiment scores, or made the subjects of topics. We can structure texts to be read by algorithms, not human beings, and cause those algorithms to perceive the results to be better than any masterpiece currently in the canon.

When producing textual works to be used in corpus analysis individual or large volumes of “poisoning” works can be used to skew the results of analysis of the body of work as a whole. The popular tf-idf algorithm relates properties of individual texts to properties of the group of texts being analysed. Changes in one text, or the addition of a new text, will skew this. Constructing a text to affect the tf-idf scores of the works in a corpus can change the words that are emphasized in each text.

The literature that these methods will produce will resemble the output of Exquisite Code, or the Kathy-Acker-uploaded-by-Bryce-Lynch remix aesthetic of Orphan Drift’s novel “Cyberpositive“. Manual intervention in and modification of the generated texts can structure them for a more human aesthetic, concrete- or code-poetry-style, or add content for human readers to be drawn to as a result of the texts being flagged by algorithms, as with email spam.

When producing images for individual analysis or analysis within a small corpus (at the scale of a show, series, or movement), arranging blocks of colour, noise, scattered dots or faces in a grid will play into algorithms that look for features or that divide images into sectors (top left, bottom right, etc.) to analyse and compare. If a human being will be analysing the results, this can be used to draw their attention to information or messages contained in the image or a sequence of images.

When producing image works for corpus analysis we can produce poisioning works with, for example, many faces or other features, high amounts of entropy, or that are very high contrast. These will affect the ranking of other works within the corpus and the properties of the corpus as a whole. If we wish to communicate with the human operators of algorithms then we can attach visual or verbal messages to peak shift works, or even in groups of works (think photo mosaics or photobombing).

The images that these methods will produce will look like extreme forms of net and glitch art, with features that look random or overemphasized to human eyes. Like the NASA ST5 spacecraft antenna, their aesthetic will be the result of algorithmic rather than human desire. Machine learning and vision algorithms contain hidden and unintended preferences, like the supernormal stimulus of abstract “superbeaks” that gull chicks will peck at even more excitedly than at those of their actual parents.

Such image and texts can be crafted by human beings, either directed at Digital Humanities methods to the exclusion of other stylistic concerns or optimised for them after the fact. Or it can be generated by software written for the purpose, taking human creativity out of the level of features of individual works.

Despite their profile in current academic debates the Digital Humanities are not the only, or even the leading, users of algorithms to analyse work in this way. Corporate analysis of media for marketing and filtering uses similar methods. So does state surveillance.

Every video uploaded to YouTube is examined by algorithms looking for copyrighted content that corporations have asked the site to treat as their exclusive property, regardless of the law. Every email you send via Gmail is scanned to place advertisements on it, and almost certainly to check for language that marks you out as a terrorist in the mind of the algorithms that are at the heart of intelligence agencies. Every blog post, social media comment and web site article you write is scanned by search and marketing algorithms, weaving them into something that isn’t quite a functional replacement for a theory. Even if no human being ever sees them.

This means that algorithms are the paradigmatic audience of culture generally in the post-Web 2.0 era.

Works can be optimized to attract the attention of and affect the activity of these actors as well. Scripts to generate emails attracting the attention of the FBI or the NSA are an example of this kind of writing to be read by algorithms. So are the machine-generated web pages designed to boost traffic to other sites when read by Google’s PageRank algorithm. We can generate corpuses in this style to manipulate the social graphs and spending or browsing habits of real or imagined populations, creating literature for corporate and state surveillance algorithms.

Image generation to include faces of persons of interest, or with particular emotional or gender characteristics, containing particular products, tagged and geotagged can create art for Facebook, social media analytics companies and surveillance agencies to view. Again both relations within individual images and between images in a corpus can be constructed to create new data points or to manipulate and poison a larger corpus. Doing so turns manipulating aesthetics into political action.

Cultural works structured to be read first by algorithms and understood first through statistical methods, even to be read and understood only by them, are realistic in this environment. Works that address a human audience directly are not. This is true both of high culture, studied ideologically by the algorithms of the Digital Humanities, and mass culture, studied normatively by the algorithms of corporation and state.

Human actors hide behind algorithms. If High Frequency Trading made the rich poorer it would very quickly cease. But there is a gap between the self-image and the reality of any ideology, and the world of algorithms is no exception to this. It is in this gap that art made to address the methods of the digital humanities and their wider social cognates as its audience can be aesthetically and politically effective and realistic. Rather than laundering the interests that exploit algorithmic control by declaring algorithms’ prevalence to be essentially religious, let’s find exploits (in the hacker sense) on the technologies of perception and understanding being used to constructing the canon and the security state. Our audience awaits.

The text of this article is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.