Dual

Nottingham Playhouse

5 September – 30 October

After a glorious false start in the 1990s, the previously over-hyped technologies of virtual reality have been quietly reclaimed in a more sustainable and democratic way through Free Software and Open Source hardware. The show “Dual” at Nottingham Playhouse showcases art that mostly uses these new technologies. A theatre is the perfect setting for the reality play of virtual reality. Curatorial collective The Cutting Room (Clare Harris and Jennifer Ross) have organized the funding, production, and presentation of artworks that mix the virtual and the real in creative ways.

Michael Takeo Magruder’s “Deconstructed Metaverse” (with Drew Baker and Erik Fleming), 2012, is installed on the upper landing of the theatre. The windows on the landing have been glazed with images of warmly coloured softly undulating colours. On closer inspection they are pixellated and have endless lines of computer code superimposed over them in small white type. The code is XML representing a virtual world, and that virtual world can be seen and interacted with on monitors in front of the windows. They display a ceiling-less ultra-modern rotunda with windows glazed in images of the views that could originally be seen through the real windows that are now glazed with images of the site-specific virtual world.

The first, smaller, monitor sits on a plinth alongside the circuit board that runs the virtual world using OpenSim under GNU/Linux from a single USB memory stick. You can use a keypad to explore the world, your presence there represented by a generic default human avatar that walks and flies around the island. Or you can visit the virtual world over the Internet. In either case, a large screen further along shows a rotating view of the island, its architecture and inhabitant(s).

Magruder has worked with virtual environments since the VRML era, and “Deconstructed Metaverse” continues some recurring themes while bringing them to a new level. There are multiple layers of reality and presence to this work that the viewer can find themselves looking into and out from, relating to other onlookers as part of the audience or part of a performance in the virtual world themselves.

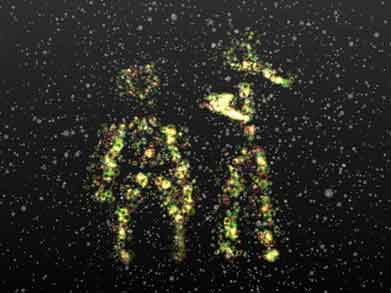

Brendan Oliver’s “Particulation” uses a Microsoft Kinect to capture the poses and motion of pairs of patrons walking through the Playhouse’s ground floor bar. A laser-scanning motion tracker and the software to process its input would have been unobtainable for most artists a decade ago. Oliver makes good use of hardware that was liberated against the wishes of its manufacturers and of software frameworks that are shared more freely.

Oliver uses them to capture and evoke the movements of two people who may not realise that they are the inspiration for the visual art on the wall. They are translated into a particle system of bubbling circles of light projected just far enough away from the sensor that monitors them that the connection between captured movement and animated image is not immediately obvious from all angles. Particulation has the feeling of joyous discovery and exploration that the best interactive multimedia art can bring to a space.

Below ground, “Mirror On The Screen” by Charlotte Gould and Paul Sermon uses similar technology to Deconstructed Metaverse to create a pocket universe of symbolic scenery and objects from children’s stories. In order see the screen presenting the virtual world and use the keypad to move your avatar around it you must stand in front of a printed backdrop where you are watched by a webcam. The resulting video stream is fed into the virtual world and superimposed onto cracks in its reality.

In addition to seeking the highest place in the forest, the edges of the world, and all the objects and characters within it, you find yourself hunting your own reflection. The tables are turned as the avatar you are watching starts watching you, and your purpose becomes seeking out further reflections. The setting of the theatre puts the viewer in a frame of mind open to the drama of the virtual world and its looping back on reality. Far from jolting you out of the experience, suddenly being faced with your own image in the virtual world draws you in further.

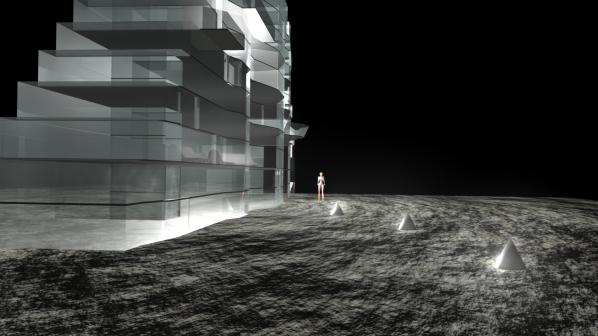

Finally, Kim Stewart’s “Sigma 6” is a 3D computer animated film set in a dystopian high modernist moonbase-like environment of harsh architecture and harsher treatment. The virtual world-like quality of the animation, and the avatar-like quality of its persecuted protagonist have their reality punctured in a way that continues the theme of mixed realities in a way that turns towards body horror.

These common themes of blurring virtual environments with real bodies and places allow the works to complement and distinguish themselves from each other artistically and technically. The Cutting Room are to be applauded for assembling such a thematically tight and technologically competent show that both serves and is served so well by the context of the institution that it is staged in.

http://www.nottinghamplayhouse.co.uk/about-us/the-cutting-room/

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.