Featured image: Image from “Otherworldly” at Manchester Urban Screens 2007. Curated by Michelle Kasprzak

Eva Kekou interviews Michelle Kasprzak, a Canadian curator and writer based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She is a Curator at V2_ Institute for the Unstable Media and the Dutch Electronic Art Festival (DEAF). She has appeared in Wired UK, on radio and TV broadcasts by the BBC and CBC, and lectured at PICNIC. In 2006 she founded Curating.info, the web’s leading resource for curators. She has written critical essays for C Magazine, Volume, Spacing, Mute, and many other media outlets. She is a member of IKT (International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art). Michelle is also an avid weightlifter with current personal records of 80 kg squat, 52.5 kg bench press, and 90 kg deadlift.

Eva Kekou: Can you give us some info about your work as an artist and curator and specifically your work at V2_?

Michelle Kasprzak: I was trained as an artist, but my art career feels many moons ago now. My first love was photography, and I spent many hours in the darkroom as a teenager. Later on I moved into live video mixing for performance contexts and parties, single channel video works, and integrating technologies like speech recognition and found objects into performance.

I was also curating throughout this time, though for many years it took a back seat to my artistic practice. Eventually I realized that I was more interested in curating and writing than making the artworks myself. Of course, one should never say never, so I may return to art making someday, but from that point onward and until the present time I focused full-time on curating and writing.

This was the mid 2000s and it was a pretty exciting time to be a media arts curator. It felt as though things were gaining traction. So many years after Cybernetic Serendipity had laid the foundations, we had exhibitions such as The Art Formerly Known As New Media curated by Sarah Cook and Steve Dietz to stimulate the dialogue about new media art and how to exhibit it, and take it all to the next level.

Fast forward to now: a few years later, I’m a curator at V2_ Institute for the Unstable Media in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. V2_ loomed large for me as a young undergraduate in Toronto studying new media – it was this far away place in a city I didn’t know with this massive reputation for doing edgy, interesting things. I wouldn’t in my wildest dreams at the time ever imagine I would one day work there.

As an institute, V2_ has been through a number of key transformations and I think it’s interesting to map that on to what was happening at the time both in art and in society. It started in the 1981 as a squat (which was common in the Netherlands at that time) and the founders called it a “multimedia centre”. Sonic Youth, Laibach, and Einsturzende Neubauten played there. The “Manifesto for the Unstable Media” was written in 1987 and arose out of a dissatisfaction with the status quo and it said things like “Our goal is to strive for constant change”. Following the Manifesto, a series of “Manifestations of the Unstable Media” were created, which evolved into the Dutch Electronic Art Festival (DEAF), a festival which continues today. In 1994 V2_ moved from s-Hertogenbosch to Rotterdam and has remained there ever since.

Around that same period of the mid- to late-90s, the growth of internet access and support for artists working with networked technologies caused V2_ to change its focus in this direction. In 1997, V2_Lab opened as a hub within V2_ to initiate and support the production of artistic projects investigating contemporary issues in art, science, technology, and society.

EK: So today, in this age of ubiquitous technology and information, where does an institute like V2_ find its place?

MK: I see media art as a category splintering and dissolving, with bits of its ethos absorbed into design, contemporary art, craft, and hacker culture – and vice versa. One way to find a place in the world is to stay true to the origins of V2_ in terms of its squatter ethic. So for example, we (myself and my colleagues, particularly Boris Debackere and Michel van Dartel) recently rewrote the mission statement of the Lab, declaring it “…an autonomous zone where experiments and collaborations can take place outside of the constraints of innovation agendas or economic and political imperatives.” Which is not to say that anything goes, but states explicitly that we’re especially open to people looking for a home for a risky or unconventional idea. Also, following on from several years where V2_Lab hosted residents based on three fairly technologically-driven themes (wearables, augmented reality, and ecology), the Lab has taken on a new direction of being methodologically-driven, and looking at themes like re-enactments, design fiction, and extreme scenarios.

I think it’s a key shift, because in order to “strive for constant change” as we said in the original manifesto, linking to any one technology of the moment seems too static and limiting, as well as reducing our reach into areas with interesting and relevant artistic research occurring, but which might not have much technology involved in an apparent way. The fact is just about everything being made right now is a product of the technological age we live in, so it’s more useful to think in terms of methods and approaches rather than whether something fits a classic definition of what media art is or not.

Take for example one of our latest commissions, Paper Moon by Ilona Gaynor in collaboration with Craig Sinnamon. Ilona and Craig were at V2_ for a few months at the end of 2013 and both have design backgrounds. The work, to describe it in a formal sense, is a series of objects and paper-based work arranged in a specific fashion along with a short screen-based animation. This seems a little different than what one might expect to see at V2_, except for small clues in the creation of some of the items (the animation is generated with 3D animation software, some of the objects have been 3D printed). But more significantly, in its thematic Paper Moon enters the realm of the unstable by exploring the emerging legal definitions and loopholes of outer space – particularly the treatment of the moon and other celestial bodies. Our legal system on Earth, as Ilona put it “…has no definition for what ‘Outer Space’ actually means, what it is, and where it is. The problem we face with such literal unmarked territory is the emergent field of ‘Space Law’ becomes genuinely speculative.”

Ilona’s residency was part of V2_Lab research project Habbakuk, about Innovation in Extreme Scenarios. The Innovation in Extreme Scenarios research thread was generated in reaction to the introduction of an innovation agenda for the arts as part of the Dutch government’s ambitionto be “one of the world’s top five knowledge economies” by 2020. As a way of directly addressing this policy direction, V2_Lab began undertaking research into the nature of and appropriate contexts for innovation through a series of expert meetings, workshops, site visits and interviews over the course of 2013-14. The final outputs of the project, which will comprise project commissions and a final publication, will be used as a tool to engage with the policy conversation on innovation in a more profound way. So we’ve been doing work on this at home and abroad, holding expert meetings and interviews in the Netherlands, Canada, Hungary, and Denmark.

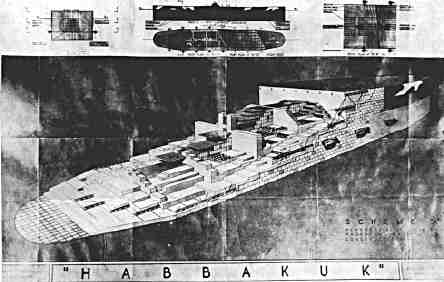

The Dutch policy context explains the “innovation” part, but the “extreme scenarios” part came from somewhere else. For that I was inspired by the World War II story of the Habbakuk aircraft carrier which was commissioned by Winston Churchill. The Allies were plagued by German U-boats, and Churchill desperately needed an innovative solution to this particular problem. In the extreme scenario of war, Churchill authorized the production of a radically innovative solution: building an aircraft carrier made of ice – specifically Pykrete, a frozen mixture of water and sawdust.

Pykrete seems like ordinary ice but the addition of sawdust makes it into a kind of wonder material that takes longer to melt and invulnerable to bullets. In the end the massive ship, which was to be christened “Habbakuk”, never saw the theatre of war but considerable effort was put into developing a prototype in total secrecy deep in the Canadian Rockies.

Inspired by both the Habbakuk story and our own policy situation brewing at home, some of the questions we’ve been trying to answer with this research are things like: What are the best contexts for innovation to take place? What are the myths surrounding how innovation occurs? Does the pressure of an extreme scenario inspire innovative solutions, or only eccentric, unrealisable concepts? What’s the U-boat problem of today?

The theme of Innovation in Extreme Scenarios is also being explored in the programme that I devised and curate at V2_ called Blowup. Blowup refers to a number of things: the way that you can blow up a photograph, a balloon, a situation, and of course – the Antonioni film. I see it as a container that presents things in a slightly different way each time, and that its main remit is to examine the things that are changing the way we live now, or reinforcing the status quo of today. The formats for Blowup have varied a lot: from a workshop, to a talk show, to a talk show within a talk show, to a five day booksprint, to an exhibition in a pop-up space. The topics have been equally eclectic: art for animals, outer space, journalism as an art practice, object-oriented ontology, and so on. The most consistent element is that each event has an eBook released along with it, and that these eBooks explore the topic in a little more depth, but also combine previously released material with newly commissioned material. We all have bulging bookshelves and intend to always read something later – by bringing relevant old texts back into the forefront, I hope to give them a chance for a second look (or a first look if you missed it when it was released).

EK: What are your hopes and dreams for the future?

MK: For the future, I think new ideas are incredibly rare, and that doesn’t bother me at all – what interests me is that dreams that were previously impossible are becoming possible, and so my passion continues to be seeking out the inventive eccentrics with grand master plans, and being a part of realising that. Churchill dreamed of ending the war with a boat made of ice more than ten times the size of the Queen Mary. These are the kinds of big wild dreams – in scale and in scope, if not in my discipline – that I dream of.