Our times are characterized by the accelerating collapse and redrawing of multiple borders: between nation states, personal identities, and the responsibilities we have for each other. Also between the old distinctions, work and pleasure.

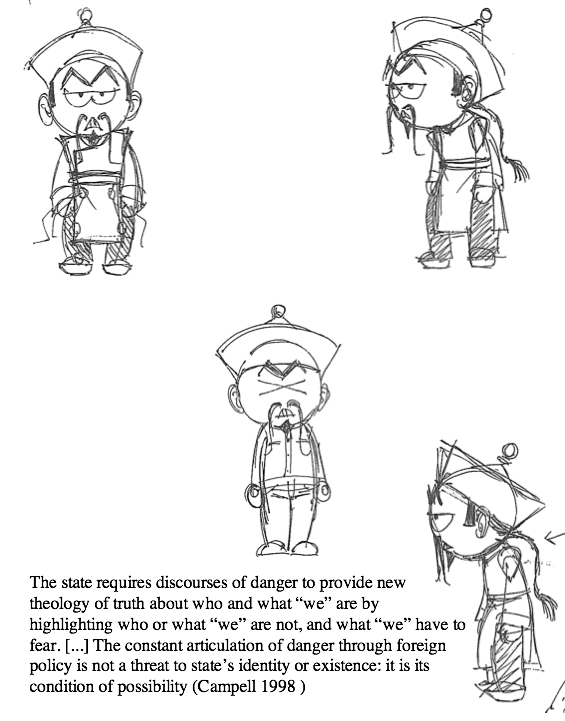

Some leaders as part of the new world order, tell us through their political actions and their fashion accessories, that they “Just Don’t Care”. This “political art-form”1 of not caring permits an insidious spread of hatred online and on the ground. In recent times, the digital condition has lent it’s networks and platforms to this poisonous, rhetorical hyperbole, turning against immigrants, and others who do not fit into the framework of a western world, oligarch orientated vision. Mass extraction and manipulation of social data has facilitated the circulation of fake news and the production of fear, anxiety and uncertainty. Together these fuel the machine of structural violence adding to the already challenging conditions created by Austerity policies, growing debt and poverty.

In the face of these outlandish difficulties our digital tools and networks – taken up with a spirit of cultural comradeship. More inspiring narratives are emerging from across disciplines and backgrounds, to experiment with new solidarity-generating approaches that critique and build platforms, infrastructures and networks, offering new possibilities for reassessing and re-forming citizenship and rights.

The exhibition and labs for Playbour – Work, Pleasure, Survival, have created new contexts for collaboration. Artists (from the local area and internationally), game designers and architects, come together with researchers from psychology and neuroscience addressing the data driven gamification of life and everything.

In her interview, the curator Dani Admiss discusses how they reassess the power relationships of the gallery, park users and the local authorities, asking who owns the cultural infrastructure and public amenities – and so create a polemic to open up questions of public value. The exhibition is open every weekend through 14 July to 19 August 2018.

The artists featured in Transnationalisms exhibition curated by James Bridle address the effect on our bodies, our environment, and our political practices of unstable borders.

“They register shifts in geography as disturbances in the blood and the electromagnetic spectrum. They draw new maps and propose new hybrid forms of expression and identity.”2

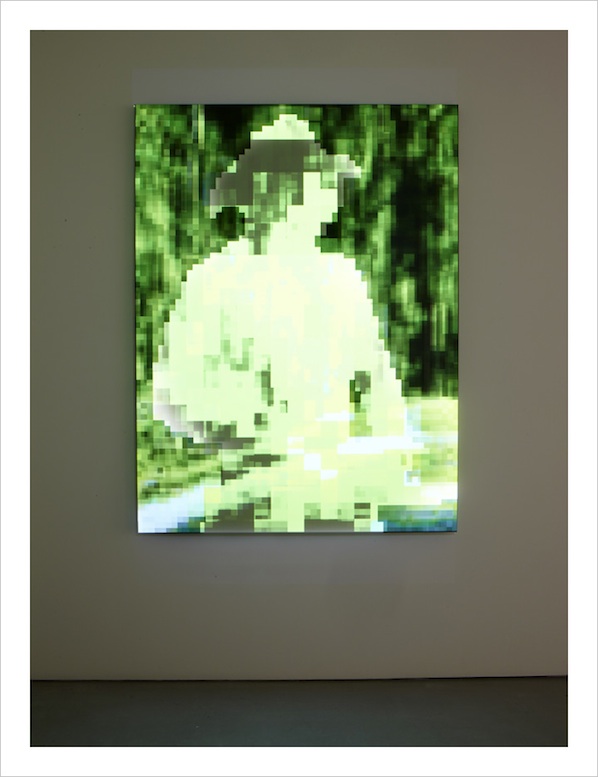

“Thiru Seelan, a Tamil refugee who arrived in the UK in 2010 following detention in Sri Lanka during which he was tortured for his political affiliations, dances on an East London rooftop. His movements are recorded by a heat sensitive camera more conventionally often used to monitor borders and crossing points, where bodies are identified through their thermal signature.”3

The show opens at Furtherfield from September 14th to October 26th 2018, touring as part of State Machines the EU cooperation which investigates the new relationships between states, citizens and the stateless made possible by emerging technologies.

We have another interview with artist and activist Cassie Thornton, where we discuss her current project Hologram, which examines health in the age of financialization, and works to reveal the connection between the body and capitalism. Her interview focuses on a series of experiments that actively counter the effects of indebtedness through somatic – or body – work including her focus on the way in which institutions produce or take away from the health of the artists and workers they “support”.

“In my work for the past decade, I have been developing practices that attempt to collectively discover what debt is and how it affects the imagination of all of us: the wealthy, the poor, the indebted, financial workers, babies, and anyone in-between.” Thornton

Finally I interview Tatiana Bazzichelli, artistic director and curator of the Disruption Network Lab, in Berlin, questions about art as Investigation of political misconducts and Wrongdoing. Since 2015, the Disruption Network Lab has cultivated a stage and a sanctuary for otherwise unheard and stigmatised voices to delve into and explore the urgent political realities of their existence at a time when the media establishment has no investment in truth telling for public interest.

“When the speakers are with us and open their minds to our topics, I feel that we are receiving a gift from them. I come from a tradition in which communities, networks and the sharing of experience were the most important values, the artwork by themselves.” Bazzichelli.

The programme creates a conceptual and practical space in which whistleblowers, human right advocates, artists, hackers, journalists, lawyers and activists are able to present their experience, their research and their actions – with the objective of strengthening human rights and freedom of speech, as well as exposing the misconduct and wrongdoing of the powerful.

To conclude, all one needs to say is…

“Whether in the variety of human, backgrounds and perspectives, biodiversity or diversity of technologies, coding languages, devices, or technological cultures. Diversity is Proof of Life.” Ruth Catlow, 2018.

Way back in 1995, the artist collective Critical Art Ensemble (CAE), said “What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself. The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world.” These words now haunt us, and take their place alongside numerous other ignored warnings about global threats to the wellbeing of our societies and the planet.

In this interview with curator Dani Admiss, we discuss how the data-driven gamification of life and everything has shaped the development of Playbour – Work, Pleasure, Survival at Furtherfield and why the Gallery is currently being transformed into a psychological environment.

Gallery visitors are presented with a series of game-like installations, which are the result of the shared and collective cognitive labour of artists, curators and gallery staff. First the artists, and then the public (as players) are invited to test the processes and experiences offered by new mechanisms of play and labour. Each ‘game’ simulates an experience of how some techniques and technologies of gamification, automation, and surveillance, are at work in our everyday lives, in order to capture all forms of existence.

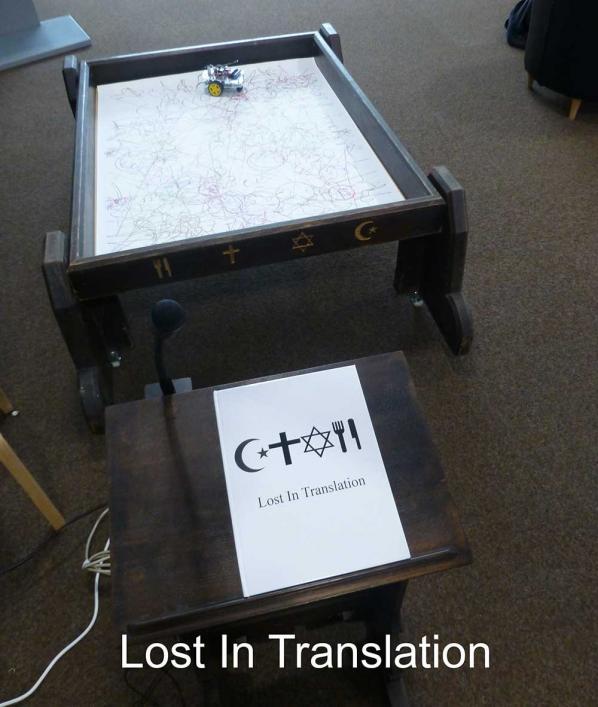

Marc Garrett: Before the exhibition, you initiated an open call for a Lab. You invited participants to join a three-day art and research lab at Furtherfield Commons, Finsbury Park, London. Could you elaborate why you did this and how it informed the exhibition?

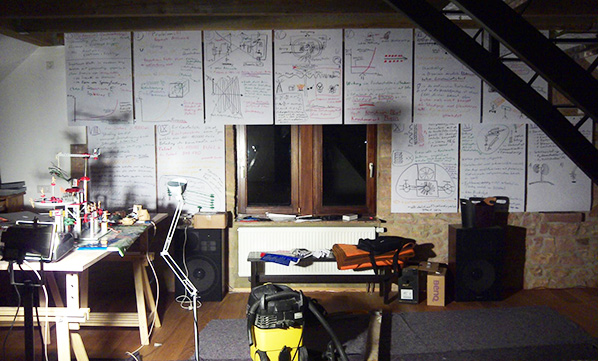

Dani Admiss: A couple of months before the exhibition, I ran a 3 day co-research lab that brought together artists, designers, activists, and researchers. I like to refer to it as a performative, temporary exhibition in the form of a lab. There were discussions, performances, interventions, games, and exercises. We had discussion with Jamie Woodcock on gaming and digital labour, he walked us through an interview session with gamers on the Twitch platform. Steven Levon Ounanian held a performative experiment where we thought about how we might render the suffering online in the real world, Itai Palti worked with us to think about design principles and neuroscience. FUN! The idea was that we would collectively explore, discuss and define key issues that we thought were important to then take forward to develop into games and experiences to share with the public. The aim was to play off each other in a live context to generate new perspectives and ideas.

Building on this, I decided to hold an open call for participants. In my most idealistic moment, I’d say I wanted to try and find ways to expand who gets to produce, stage and display, how we define what these issues actually are for wider audiences. Can this lead to new stories about art, tech, society? Like any project it is never exactly as you imagined it, but I think the majority of people got a lot out of working like this. I did. Working with people that aren’t always the people you expect to be attached to a project always throws up unexpected experiences. Everyone brought their best themselves with them. Open. Interested. Warm. Prepared. Ready to listen, and for fun!

I’d make the lab longer next time, so it wasn’t as intense, and I’d try to have more people join the open call.

MG: The open-curation process you have developed is core to the realisation of the Playbour lab and exhibition. It resonates strongly with Furtherfield’s DIWO ethos. It turns on its head, the traditional approach to curating thematic group shows. Please can you tell us about the process and say why this new approach is important at this time?

DA: DIWO definitely informed Playbour! I think the spirit of co-creative discovery is a powerful tool that curators should use more. I refer to it as co-research, which is ultimately a way to research-with others. What separates it from more traditional approaches to curating is the unclear distinction between author/researcher and subject/participant. The aim is to achieve closer equality between the participant and subject area, in the form of valuing a person’s idea’s and lived-experience as much as other ‘expert’ forms of knowledge. Historically, it has roots in a highly specific context of the radical Left in post-war Italy with Operaismo. This is where the seeds of debate on post-immaterial labour emerged, arising from Hardt, Negri, Bifo, Terranova, etc, and why I originally was interested in working in this way because of the subject matter of the project, however, it became something so much more.

For me, as a curator, creating projects about complex subject areas that bring together embodied and embedded social relations with technical worlds, is something that needs to be done with people rather than to them. I think the most interesting works of art being produced today are treated less like things and instead draw into the very making of the ways in which we get to know what we know. You can see this in works from Cassie Thornton’s project Collective Psychic Architecture (an exploration of “bad support” in Sick Times) 2018, where she extends the responsibilities of the gallery or institution through performative means, or in the high-profile modeling and mapping practices coming out of the Forensic Architecture network. How can curating exist in a wider space than before? I’m trying to work in much more extended and expanded ways with the primary intention to include more end users into the areas we are looking at.

Adopting a co-research model (in the lab, in the show, in the publication, in the micro-commissions) meant that the aim of the exhibition shifts, it becomes less about what the topic is and how it works and more about how it came to be. Brian Holmes once wrote that making an image remakes the world. Yes, but it also distances us from it. Playbour asks people to consider how the world organises us by facilitating moments where people can identify with particular phenomena. I feel this is more fitting and has more potential to create moments of personal learning and change than trying to represent it through curatorial practice. Why do we need this in an age of information? My thinking is that knowledge-projects are not simply objective processes but deeply subjective ones that are enacted through and with others. Finding ways for people to identify in more meaningful ways with the subject will hopefully lead to greater chance that people will gain greater perspective and agency over their own worlds.

MG: The term Playbour brings attention to critiques of gamification and to the extraction of value via social media platforms. But your subtitle then opens up a whole other world of reflection. What are you discovering about the relationship between “work, pleasure and survival”?

DA: The project is exploring the role of the worker in the age of data technologies, but this looks less at the “future of work” and chooses instead to focus on the shifting roles and blurred boundaries of work, play and well-being – how do we place value on these areas, how do we work with and against them?

Quite often when we talk about opaque terms like immaterial labour and cognitive capitalism we fail to grasp the production processes of these phenomena. Immaterial labour depends on the self and our social relations. We are asked to ‘post’, ‘share’, ‘network’, ‘emote’, ‘communicate’, ‘know’. Not so much ‘understand’. These acts inform the control and creation of our subjectivity. At the same time, very little discussion is happening about the fact that so much exploitation -physical, ecological, economical- sits behind the new commons we are all talking about.

Opening the project out to think about work, pleasure, survival, is a provocation. On one level, it is a nod to the fact that this conversation is for a privileged few. Many choose what they do and this ‘choice’ is supposed to operate as an expression of one’s personality. On the other, it’s human nature to get swept up in what is considered the norm, so it’s also a challenge to think about what are your own limits, returning to the idea of inviting people to find moments of identification with these broader issues to their own lived experience.

MG: Why is it important that the work being prepared for Furtherfield gallery is conceived of more, as a series of game experiences, than a display of discrete art objects, or a didactic exhibition on the topic of Play and Labour? Has the gallery’s location in a public park influenced your thinking at all?

DA: Well, first off, it has been a collective process and so I wanted to show that process to people. Secondly, you have to invest part of yourself in play. The more I research the areas of digital and immaterial labour the more I’m keen to work with others to understand the not yet completed transformations of body, society, and world, into a global capitalist system. These are suffuse and pervasive and nudge our behaviours all of the time. Organising the exhibition as experiences is a way for us all to live-out (at least temporarily and in a safe, playful space) the tentacular effects of immaterial labour and economies of knowledge and information. This is not to say let’s walk away from a highly networked society, it’s an invitation back into perspectival agency.

MG: You’ve chosen to put together three themes for the exhibition, ranging across work, pleasure, and survival. Why was it important to choose these three themes in particular?

DA: I’m fascinated by how we are involved in the making of worlds we are then conditioned by. From the learnings in the lab, my own research and collaborations leading up to Playbour, I think gamification, automation, and surveillance are three key areas that scaffold a lot of the debate on digital and immaterial labour.

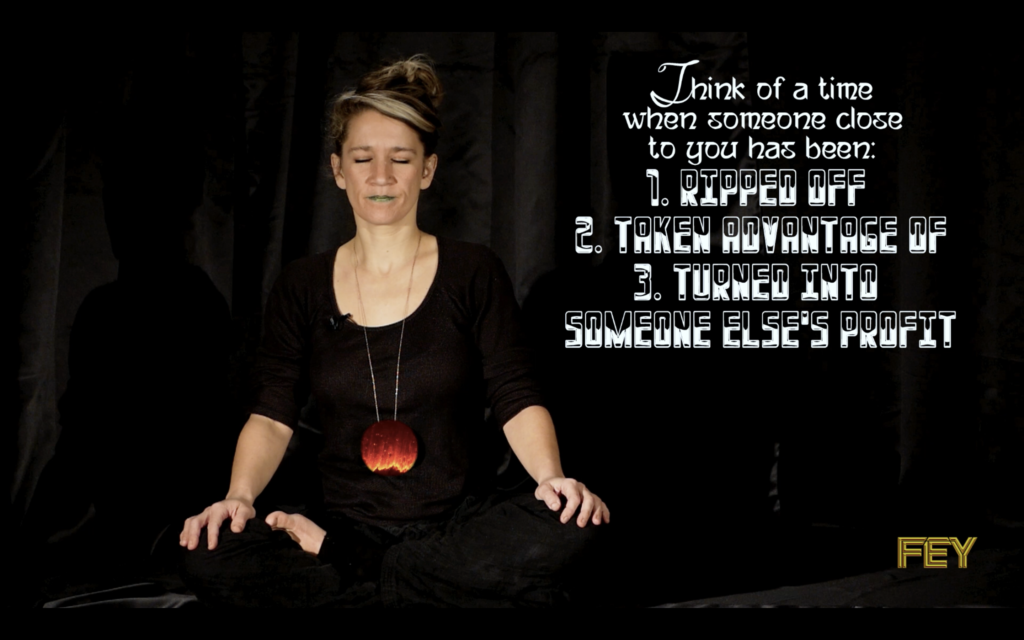

1) SURVEILLANCE. How we are measured and how we measure ourselves? Traditionally, government control used to come from top-down surveillance techniques, such as the type Michael Straeubig’s Hostile Environment Facility Training (HEFT) is looking at. However, I think we should be talking about how forms of control are exercised through our own self-monitoring processes – self-improvement culture is a perfect example of this. Cassie Thornton’s Feminist Economics Yoga (FEY), is a wonderful remedy for this.

2) AUTOMATION. How technology is removing decision-making from us in the pursuit of a frictionless universe. In Harrison-Mann’s Public Toilet he is talking about how automation is used to address the need of social issues. The starting point is the lack of public services offered in Finsbury Park and how that is altering how we use and experience the public space of the park. He is interested in making a connection between this and how metrics can often end up being exercised in controversial and even arbitrary ways inhibiting people getting what they need, such as disability benefits in the UK.

3) GAMIFICATION. How are rewards and competition embedded into our online interactions and interfaces? Jamie Woodcock has this excellent term that describes gamification-from-above and gamification-from-below. Like the Situationist socialism-from-below. How we might use gamification for our own positive manipulations, diversions and distractions? I think a lot of media and new media practice has long been engaged in gamification-from-below. Marija Bozinovska Jones’ piece Treebour (201) plays on this, transferring manipulation of social relations levelled at online interactions to the “natural” networking of trees.

MG: After visitors have experienced the exhibition, what emotions, thoughts and understandings, would you like them to leave with?

I think you introduced the show in an interesting way in your opening text with the notion of the data body and the extension of our bodies into new spaces with unknown consequences. These happen inside the screen, at the edges of the world, in transit, at the end of the supply chains. At the same time, they also operate on semi-conscious refrains, in our behaviours, actions, thoughts and emotions about the world. Taking part, thinking-with, making-with, are strategies to find ways to open up discussions about how we are all involved in making and unmaking our worlds via different actions. Something like digital and immaterial labour is not a discrete issue reservable for experts who work in this area, the connections and consequences weave in and out of our lives and impact us all. We are constantly reacting to thing around us, taking in these cues and pushing them back out into the world.

In terms of emotions, I don’t want to spread fear and despair, I’m hoping that some visitors will identify with some of the ideas in the show and relate them to something in their life that perhaps they’d not thought of in that way before.

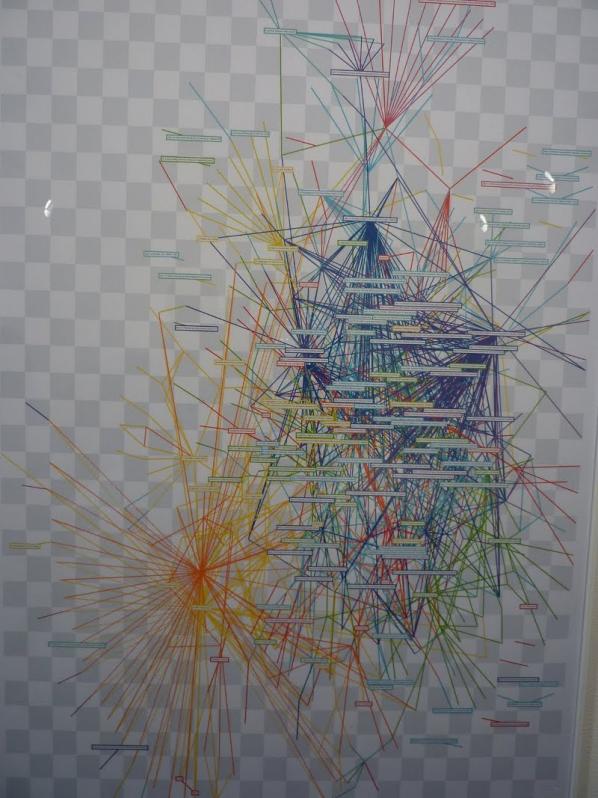

Notes: Main top image by Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour 2018.

DIWO – Do It With Others: Resource

archive.furtherfield.org/projects/diwo-do-it-others-resource

Compiler is an experimental platform organised by curator Alisa Blakeney, artist-curator Tanya Boyarkina, artist Oscar Cass-Darweish and choreographer Eleanor Chownsmith, all currently students of MA Digital Cultures, Goldsmiths. The platform is being built in order to “support collaborative, process-driven projects which connect artists and local communities in networks of knowledge-exchange”.

The organisers of Compiler describe it as a kind of ongoing prototype, a structure constantly negotiating the openness to maintain links to varied practices with the coherence of framing, containing, and describing some of the complicated products of digital-analogue interactions. Their focus is looking at what ‘digital culture’ means and having a productive conversation about it.

From 6-8 April, the first Compiler, Play Safe took place downstairs at OOTB in New Cross. The exhibition examined practices of surveillance inherent in “states, corporations, technological spaces and the idioms of digital art”. It questioned whether an increasing intensity of surveillance is linked to control, extraction and politics, or can be understood as a pleasurable phenomenon. People were invited to “Dance a website, see through the eyes of a computer, and have our cryptobartender mix you a cocktail to cure your NSA woes”. The work on show, made by students from MA Computational Arts and MA Digital Cultures (both Goldsmiths), included Eleanor Chownsmith’s software and performance which turned website HTML into dance routines, Michela Carmazzi’s photographic project documenting the reactions of Julian Assange and his supporters following the United Nations’ ruling about his case, and Saskia Freeke’s machine which repeatedly and intentionally failed to create a ticker-tape parade using sensors and fans.

An exhibition on the theme of surveillance creates a strange grey area for itself when shown in a building with nine screens of CCTV footage. Oscar Cass-Darweish’s project made a fairly direct link to the CCTV cameras which emphasised this greyness. The project produced a rendering of the exhibition space by using a function usually found in motion detection processes. This function calculates the difference in pixel colour values between frames at a set interval and averages them, creating a visual output of how machines calculate difference over time.

Another work which made links with the room upstairs was Fabio Natali’s Cryptobar, where following an interview with the ‘bartender’ about your data privacy needs you were recommended a cocktail of data-encryption software. Upstairs you could buy, and drink, a cocktail with the same name (the Cryptobar was part of the V&A Friday Late on Pocket Privacy on 28 April).

So far, Compiler has made a variety of spaces for conversation about digital culture through both its artworks and its organisation. Each artwork has a different ‘footprint’ of interactions, linking websites to rooms, success to failure, data privacy to financial transaction via consultation, and making interesting connections between CCTV and code, dance notation and HTML, activism and commerce.

An interesting way to read the Compiler platform is as a series of combinations of human-readable codes and machine-readable codes. The platform ‘compiles’ a different combination each time, and each time the output is different. Through this, the interaction of analogue and digital processes is demystified and muddled, in a distinct way. The platform is in its early days, but it seems likely that new connections and new grey areas will appear over the next few months, as Compiler has its second exhibition (again at OOTB) in May, takes part in the CCS conference at Goldsmiths in June and heads in other directions thereafter.

The exhibition offered plenty to play with, while posing complicated problems in relation to openness and experimentation. When I spoke to Eleanor, Tanya and Alisa about Compiler and its aim to engage local communities in networks of knowledge-exchange , we talked about how it’s an impossible and strange aspiration to have a ‘neutral’ venue. While a cocktail can be delicious and engaging, it’s also expensive. While a cafe is, arguably, a less exclusive space than a gallery, OOTB itself is a cafe which targets a specific audience. Drink prices, decor and a host of other factors mean OOTB, like all spaces, is politicised in a particular way. Their venue choices so far will influence, in subtle and overt ways, their future attempts to engage diverse local communities. The organisers of Compiler acknowledge this; their response is that rather than trying to make an artificial neutrality they are keen to move as the platform develops to new spaces and new and different contexts.

A change of context, message, communication style is not easy; nor does it fit with to an easily recognisable politics or aesthetics. Moving into and out of contexts is something to be done carefully and thoughtfully. It seems to me that the Compiler team will have their work cut out, but if they can direct that work in such a way that the platform is able to communicate in multiple ways at once, ‘networks of knowledge-exchange’ could develop between, and in response to, the markers set by the organisers. The question is, how will they develop?

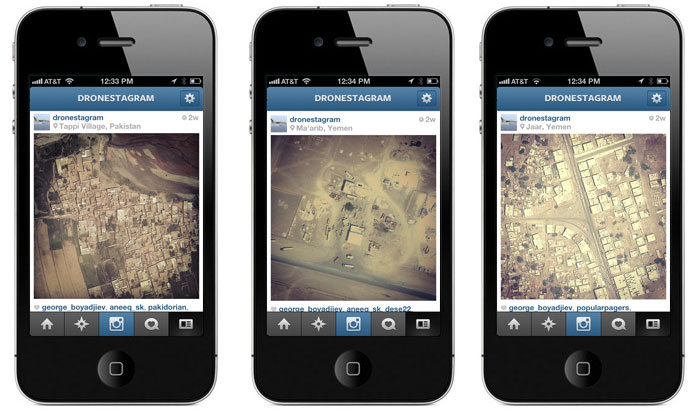

Featured image: 98.235.73.27, 2016-07-10

Nye Thompson is a London-based artist whose work explores the interface between physical and virtual domains. Her recent artwork Backdoored involves the collection and online archiving of images taken via unsecured surveillance cameras worldwide. Backdoored was featured at Internet Yami-Ichi at Tate Modern in May this year. Backdoored.io, curated by Kosha Hussain, followed as a solo show at Bank Gallery, London in August. Artist Millicent Hawk interviews Nye on the technology, aesthetics and universal conditions that make this work both compelling and uneasy at once.

Millicent Hawk: Backdoored is transparent in its approach – the website tagline reads, ‘Intrusion | Surveillance | Exposure’. And whilst there have been a few (mostly misinformed) concerns aired publicly about the invasive nature to the work since the first solo exhibition of it this year, you’re not actually a hacker and these images existed already before – can you explain how these images are taken and the issues they raise.

Nye Thompson: To me, Backdoored highlights the technological erosion of our privacy and through this work I’m exploring the factors that make us active contributors to this process. A ‘backdoor’ is slang for a feature or defect in a device that allows the bypassing of normal authentication. These images are generated by softbots belonging to specialist search engines which trawl connected devices (the Internet of Things) for security testing. The bots take pictures when they discover an unsecured camera and save them into their search results. In most cases the owner of the camera has no idea this is happening.

For some time now I’ve been interested in the Internet of Things and its potential impact on our personal privacy and liberties, but how do you create artistic discourse around something so abstractly technical? So when I first discovered these images they were revelatory for me because they provided me with a ready-made visual language to talk about these issues. There is also a performative thread running through the project: every day I get sent new images, and I attempt to unpick meaning from their apparent randomness by developing taxonomies and applying them to each one.

MH: So how does one avoid being, ahem, Backdoored ?

NT: If you have an IP surveillance camera in your home then you are basically broadcasting your domestic life onto the internet. This data needs to be protected by setting a unique, secure passcode on the camera. The images in Backdoored come from cameras that don’t have this. Part of the problem is a toxic combination of low public awareness of privacy risks combined with profit-hungry manufacturers and lack of regulation. But these Backdoored cameras are just harbingers of what is to come – a future surrounded by smart objects all collecting and sharing data about us.

MH: The word ‘Backdoored ’ implies something that’s both disturbing but potentially exciting too, although, with explicit reference to the screenshots of a child or an elderly person in bed, combined with geo-location details – it’s totally creepy. However, those particular images aside, there’s something fascinating with many of the vidcam shots. Bots are set off to capture the image at a single point of finding unsecured domains so people are captured in their domestic settings – at ease in their pants, for example. This serendipitous and incidental timing without a human-decisive moment or any playing to the camera makes these images – albeit voyeuristic – seemingly more representative of the real and something nearer to the truth. So the digital aspect to the dark world of unsecured vidcams brings me intrigue as well as valid concerns over individual rights to privacy.

NT: Yes, although images of people in their homes form only a part of the surveillance images I find; there are wastelands, machinery, bars, building sites, hidden cameras, zombie cameras – forgotten but still broadcasting. They form a kind of covert mapping of contemporary concerns and anxieties worldwide.

MH: Yes, this is different to public surveillance and government snooping which – for the most part – seems to have been accepted. Similarly to public surveillance though, home vidcams seem an unnecessary reaction to an underlying and excessive state of fear, and the voracity to control; anxieties in these images then are represented through the choice of self-prescribed surveillance.

NT: Yes, it seems like the scenes and objects in these pictures predominantly represent a kind of metaphysical anxiety, or a way to reassure ourselves of object permanence. These are things that we feel we need to monitor constantly in case something bad happens, although it’s not always clear how we would meaningfully intervene. It’s a classic case of a technology creating a need, and a new demand on our attention. Suddenly we have the ability to watch the people and things in our life 24/7, and so not watching can almost feel like a failure to care. Yet at the same time there is a distancing, as we engage with our babies, our elderly parents, our pets, our work colleagues, our possessions – as live video streams rather than through physical, embodied interaction.

MH: Thinking back to earlier this year, Backdoored was a new idea for you. And something that I – and presumably many people – weren’t even aware was happening. At the time, we discussed the premise for this work and shared our concerns of how ethics get outpaced by rapid technological development. How do you reconcile Backdoored seeing that these images bring greater intrusion to those whose privacy they reveal?

NT: This is an important question. These images are already out there for anyone to find, and more significantly millions of these cameras are insecure and vulnerable, yet, as you said, many people are not aware of these facts. Of course I am conscious that by bringing people’s attention to them I am also amplifying the images, so there are ethical and curatorial challenges here. But these images do already exist and I’m using them in a very direct way – drawing attention to privacy and surveillance issues. There’s immediacy to imagery that resonates when a full-length article might not. I think public reports on privacy issues, by organisations like Privacy International & Big Brother Watch (to name just two), are massively important but they are endlessly firefighting this international problem. Who’s to say art can’t have an effect on these issues too?

MH: Raising awareness helps – last week I made a studio visit to an artist who had a Backdoored postcard on his desk, the tape over his webcam was a recent addition since seeing your work at Tate Modern. But, further to public awareness, lawmakers, regulators, manufacturers and commercial watchdogs need to work together to ensure privacy matters. That said, state surveillance is at a insanely invasive level – I’m thinking of GCHQ’s Smurf Suite and the Investigatory Powers Bill (which targets journalists’ privacy on whistleblowers) – vidcam backdoors perhaps seem trivial for a government to attempt to regulate and, perhaps, are even a welcomed accessory to state surveillance. On the issue of state surveillance, you were faced with some rather heavy legal threats – explain.

NT: Ah yes. Backdoored.io at Bank Gallery this year triggered an official complaint from the Hong Kong Commissioner. One of the works featured domestic scenes from Hong Kong – they seem to use a disproportionately high volume of unsecured surveillance cameras in their homes. First I received legal threats from a Chinese newspaper, then Channel 4 news weighed in with a recorded complaint from the Commissioner and demanded that I give them a (pre-recorded) interview in response. They then broadcast a sensationalised news piece, using a heavily cut version of my interview. The news article attacked me for my use of these images, while at the same time deliberately obfuscating the privacy and technology issues and how the images came to exist in the first place. Ironically, a few weeks later, the media was full of reports that the FBI was advising people to put tape over their webcams to protect their privacy!

MH: Ha, fifteen years too late. In terms of the complaint from the Chinese Commissioner for Hong Kong, it seems rather duplicitous that a country with the most pervasive internet censorship to maintain control over it’s public (I understand ProtonMail has a large Chinese user base) would be interested in threatening a UK artist here – what’s the percentage of webcams that are manufactured in China?

NT: No comment 😉

MH: So what’s next for Backdoored and how do you see the future for privacy?

NT: Backdoored highlights this very real and disturbing fact – these images already exist. What does this imply for us now and what does it imply for the future? Backdoored foregrounds privacy and surveillance, although, as an artist, I’m also interested in these images as material: the social and cultural messages encoded within them; their robotic origin; and the complex responses they evoke in the viewer. These images are signifiers for some of the epic power struggles* currently taking place at the cutting edge of technological development. This surrendering of our privacy seems like a one-way ticket; once we’ve lost that could we ever get it back? What we want for our futures must be dealt with now.

* In recent weeks we have seen just how easily these unsecured cameras can be ‘weaponised’ by hackers. For example, millions of these cameras have now been infected with the Mirai and other viruses. This allows them to be conscripted into giant ‘botnet’ armies which can be used to attack or censor other parts of the Internet.

Nye Thompson’s Backdoored will be in TERMINAL, a group exhibition opening at Avalanche in December. For 2017 she is planning a UK touring show, and also a panel discussion on issues raised by the project. Event details can be found on the Backdoored website.

Contact:

@nyethompson

www.Backdoored.io

Several months ago I stayed in an offbeat Amsterdam hotel that brewed its own beer but refused to accept cash for it. Instead, they forced me to use the Visa payment card network to get my UK bank to transfer €4 to their Dutch bank via the elaborate international correspondent banking system.

I was there with civil liberties campaigner Ben Hayes. We were irritated by the anti-cash policy, something the hotel staff took for annoyance at the international payments charges we’d face. That wasn’t it, though. Our concern was intuitive about a potential future world in which we’d have to report our every economic move to a bank and the effect this could have on marginalised people.

‘Cashless society’ is a euphemism for the “ask-your-banks-for-permission-to-pay society”. Rather than an exchange occurring directly between the hotel and me, it takes the form of a “have your people talk to my people” affair. Various intermediaries message one another to arrange an exchange between our respective banks. That may be a convenient option, but in a cashless society, it would no longer be an option at all. You’d have no choice but to conform to the intermediaries’ automated bureaucracy, giving them a lot of power and a lot of data about the microtexture of your economic life.

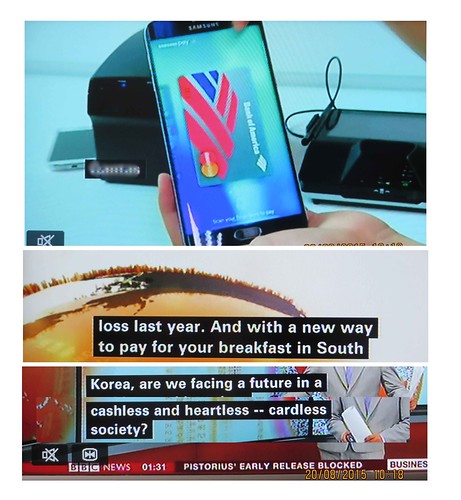

Our concerns are unfashionable. Without any explicit declaration, the War on Cash has begun. Proponents of digital payment systems are riding upon technology-friendly times to proclaim the imminent Death of Cash. Sweden leads in the drive to reach this state, but the UK is edging that way too. London buses stopped accepting cash in 2014 but do accept MasterCard and Visa contactless payment cards.

Every cash transaction you make is one that payments intermediary like Visa takes no fee from, so it has an interest in making cash appear redundant, deviant and criminal. That’s why, in 2016, Visa Europe launched its “Cashfree and Proud” campaign to inform cardholders that “they can make a Visa contactless payment with confidence and feel liberated from the need to carry cash.”

The company’s press release declared the campaign “the latest step of Visa UK’s long-term strategy to make cash ‘peculiar’ by 2020.”

There you have it. An orchestrated strategy to make us feel weird about cash. Propaganda is a key weapon of war, and all sides present themselves as liberators. Visa comes across like a paternalistic commander when assuring us that we – like a baby taking first steps – will feel a sense of achievement at liberating ourselves from the burden of cash dependence. Visa technology offers freedom without dependence or dangers.

Other propagandists join Visa. In 2014 Penny for London arrived, an apparently altruistic group set up by the Mayor’s Fund for London and Barclaycard, using charity as a hook to switch people to contactless cards on the London Underground. PayPal plastered cities with billboards claiming that “new money doesn’t need a wallet”, and a video proclaiming: “New money isn’t paper, it’s progress”. Astroturfing campaigns like No Cash Day are backed by American Express, highlighting such anti-cash themes as the environmental impact of banknotes. Other tactics include pointing out that criminals use cash, that it fuels the shadow economy, that it’s unsafe, and facilitates tax evasion.

These arguments have notable shortcomings. Criminals use many things we keep – like cars – and fighting crime doesn’t prioritise maintaining other social goods like civil liberties. The ‘shadow economy’ is a derogatory term used by elites to describe the economic activities of people they neither understand nor care about. As for safety, having your wallet cash stolen pales compared to having your savings obliterated in a digital account hack. And if you care about tax justice, start with the mass corporate tax avoidance facilitated by the formal banking sector.

However, the peculiar feature of this war is that only one side is fighting. Very few media champions defend cash. It is like a taken-for-granted public utility, whereas digital payment platforms are run by private companies with an incentive to flood the media with their key messages. When they fight this war, their target is our cultural belief in cash and the belief that its provision should be a public right.

The UK government does not plan to maintain that right and is siding with the payments industry. Their position is summed up by economist Kenneth Rogoff in his new book The Curse of Cash. He argues that, apart from facilitating crime and tax evasion, cash hampers central banks from setting negative interest rates. In the absence of cash, everyone must keep their money in the form of digital bank deposits. During recessions, central banks could then use the banking system to deliberately corrode people’s deposits via negative charges, ‘inspiring’ them to spend rather than hoard.

The emergent consensus among economic and political elites is that this is the direction to go in, but to manufacture consent for this requires a drip-drip erosion of public resistance. Hearts and minds must be shown that the change represents inevitable and desirable progress.

Anyone defending cash in this context will be labelled as an anti-progress, reactionary, and nostalgic Luddite. That’s why we must not defend cash. Rather, we should focus on pointing out that the Death of Cash means the Rise of Something Else. We are fighting a broader battle to maintain alternatives to the growing digital panopticon that is emerging all around us.

To understand this conflict, we must step back. A monetary transaction involves exchanging specific goods or services for tokens giving access to general goods and services from others. The pub landlord hands me a beer at night if I transfer tokens that allow him to get cigarettes from a shopkeeper in the morning.

There are two ways to implement this, though.

The first is to give the tokens a physical form. In this scenario, ‘getting rich’ means accumulating those physical things and ‘making a payment’ means handing them over to someone else. They are bearer instruments, which means nobody keeps a record of who owns them. Rather, whoever holds them owns them. This is your wallet with notes in it. This is cash.

Alternatively, you can use a ledger. Someone sets up a database with spaces allotted to different people. This is then used to keep a record of who has tokens. These tokens have no physical form but are written into existence. They are ‘data objects’ and are ‘moved around’ by editing the record. The keeper of the ledger thus maintains an account of what money is attributable to you, ‘keeping score’ of it for you. In this system, ‘getting rich’ means accumulating a high score on your account. ‘Making a payment’ involves identifying yourself to the keeper of the ledger via a communications system and requesting that they edit your account and the account of whoever you are paying.

Does this sound familiar? It is your bank account.

Old banks used actual books to maintain these account ledgers, but modern banks use digital databases housed in huge data centres. You then interact with them via your internet banking portal, your phone app, or by going into a branch. This is not a minor part of the monetary system. Over 90 per cent of the UK’s money supply exists nowhere but on bank databases.

It is upon this underlying infrastructure that payment card companies like Visa build their operations. They deal with situations in which someone with one bank account finds themselves in a shop owned by someone else with another bank account. Rather than the pub landlord giving me his bank details for a manual transfer, my card sends messages through Visa’s network to automatically arrange the editing of our respective accounts.

Many fintech – financial technology – startups specialise in finding ways to augment, gamify or streamline elements of this underlying infrastructure. Thus, I might use a mobile phone fingerprint reader to authorise changes to the bank databases. – ‘disruption’ merely involves putting slicker clothes on the same old emperor.

The use of high-speed communications systems to rearrange binary code information about who has what money might be new, but ledger money is as old as any bearer form. The Rai stones of the island of Yap were huge and largely unmovable stones that, while seeming like physical tokens, were a form of ledger money. Rather than being physically moved – like cash would – a record of who owned the stones was kept in people’s heads, stored in their communal memory. If the owners wished to ‘transfer’ a stone to another, they ‘edited the ledger’ of who possessed the tokens by merely informing the community. Why physically roll the stone if you can get everyone to remember that it has ‘moved’ to somebody else? The main reason that we struggle to recognise this as a form of cashlessness is that the ledger is invisible and informal.

Cashless society, though, is presented as futuristic progress rather than past history, a fashionable motif of futurists, entrepreneurs and innovation gurus. Nevertheless, while there are real trends in behaviour and tastes to be spotted in society, there are also trends in behaviour and taste among trend-spotters. They are paid to fixate upon change and have the incentive to hype minor shifts into ‘end of history’ deaths, births and revolutions. Innovation communities are always at risk of losing touch within an echo chamber of buzzwords, amplifying one another’s speculations into concrete future certainties. These prediction factories always produce the same two unprovable sentences: “In the future we will… ” and “In the future, we will no longer… “. Thus, in the future, we will all use digital payments. In the future, we will no longer use cash.

This is the utopia presented by the growing digital payments industry, which wishes to turn the perpetual mirage of a cashless society into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Indeed, a key trick to promoting your interests is to speak of them as obvious inevitabilities already underway. It makes others feel silly for not recognising the apparently obvious change.

To create a trend, you should also present it as something others demand. A sentence like “All over the world, people are switching to digital payments” is not there to describe what other people want. It’s there to tell you what you should want by making you feel in sync with them. Here’s fintech investor Rich Ricci invoking the spectre of millennials, with their strange moral power to define the future. They are repulsed by the revolting physicality of cash and feel all warm towards fintech gadgets. But these are not, on the whole, real people. They are a weapon in the arsenal of marketing departments to make older people feel prehistoric. We’re not pushing this. We’re just responding to what the new generation demands.

And so we get Visa’s Cashfree and Proud campaign. If people really were ashamed of cash, they wouldn’t need ads to tell them. Visa must engineer that shame to teach you that what you want is the same as what they want. And if you don’t want it, just remember that a cashless society is inevitable. Don’t get left behind.

But this system will leave many behind. It is hardwired to include only those with access to a bank account, and bank accounts are hosted by profit-seeking corporations that operate at scale. They have no time for your individual idiosyncrasies. They cannot make a profit off anyone who cannot easily be categorised and modelled on a spreadsheet.

So, good luck if you find yourself with only sporadic appearances in the official books of state, if you are a rural migrant without a recorded birthdate, identifiable parents, or an ID number. Sorry if you lack markers of stability if you are a rogue traveller without a permanent address, phone number or email. Apologies if you have no status symbols or are an informal economy hustler with no assets and low, inconsistent income. Condolences if you have no official stamps of approval from gatekeeper bodies, like university certificates or records of employment at a formal company. Goodbye if you have a poor record of engagements with recognised institutions, like a criminal record or a record of missed payments.

This is no small problem. The World Bank estimates that there are two billion adults without bank accounts, and even those who do have them still often rely upon the informal flexibility of cash for everyday transactions. These are people bearing indelible markers of being incompatible with formal institutional space. They are often too unprofitable for banks to justify the expense of setting them up with accounts. This is the shadow economy, invisible to our systems.

The shadow economy is not just ‘poor’ people. It’s potentially anybody who hasn’t internalised the correct state-corporate narrative of normality and anyone seeking a lifestyle outside of the mainstream. The future presented by self-styled innovation gurus has no scope for flexible, unpredictable or invisible people. They represent analogue backwardness. The future is a world of endless consumer choice built upon an inescapable digital uniformity of automated rules, a matrix outside which you can neither exist nor think.

Back in Amsterdam, I hang out with Ancilla van de Leest of the Netherlands Pirate Party. She only visits establishments that accept cash, true to her political belief in individual privacy from prying eyes.

However, it would be wrong to assume that Ancilla’s primary concern involves surveillance by a Big Brother-style bogeyman. It’s true that your spending patterns reveal much about how you actually live, and the privacy implications of having these recorded in searchable database format are only starting to be uncovered. We know that targeted individual surveillance of payments occurs by the likes of the FBI and NSA, but routinised mass surveillance could become a norm. Imagine automatic flagging systems triggered by anyone engaging in a combination of transactions deemed subversive. Tax authorities are bound to be building systems to flag discrepancies between your spending patterns and your declared profits.

It’s also true that at London fintech gatherings, the exciting visions of a cashless society occasionally come with a disclaimer that we should think about the power granted to those who control the system. Not only can payment intermediaries see every time you buy access to a porn site, but they have the ability to censor your transactions, like Visa, PayPal and MasterCard attempting to choke WikiLeaksby refusing to process people’s donations. We could imagine some harsh sci-fi scenario in which a theocratic regime issues decrees to payment processors to block anyone buying books deemed sexually deviant. Such decrees could be automatically enforced via code, with subroutines remotely triggering smart locks to place the offending miscreant under house arrest while automatically deducting a fine from their account.

Such automated dystopias should ideally be avoided, so a dose of paranoia about digital payment systems is a healthy impulse, even if it might be unwarranted.

But that isn’t really the point. What’s more important to Ancilla and me is the looming sense of an external watcher that ‘assists’, ‘guides’ or ‘helps’ you in your life, tracking and logging your moves to influence you. The watcher is not a single entity. It’s a collective array being incrementally built in stages by startups and companies worldwide as we speak. We feel it seeping deeper into our lives, a mesh of connected devices, cookies and sensors. Whether we visualise it as the benevolent eyes of a parent or the menacing eyes of a tyrant doesn’t matter. The point is that the eyes have the potential to monitor you all the time.

The proclaimed Death of Cash is thus an episode in the broader drama that is the Death of Privacy, the death of the breathing room, and the death of informal, non-measured, unaccounted-for behaviour. Every action you take must forever be attached to your digital persona, dragging a data trail extending back to the day you were born. We face creating an entire generation of people who do not know what it feels like not to be monitored.

For many economists, the War on Cash will be resolved by their favourite mystical demigod, the market. This guiding force prevails when utility-maximising producers and consumers make rational choices with perfect information about their options and total freedom to choose whether or not to exercise them. If digital payment transaction costs are lower, then the cash will rightly die.

The pristine realm of market theory is unfit to assess the dynamics of this situation. Our sense of what constitutes a legitimate choice does not form in a vacuum. We are born into social power structures that tell us what normality is and shame us for not choosing ‘correctly’. You might be a rebel who challenges prevailing cultural norms, but those norms are conditioned by those with the greatest financial and media clout. At this moment, the blaring of propaganda extolling the short-term conveniences of digital payment is dulling our critical impulses to rearrange our cultural DNA. Who is thinking about the longer-term implications of building our lives around these systems and thereby locking ourselves into dependence upon them?

Unlike a battle fought using violence, hegemony is the assertion of power by getting people to believe in it, to see it as inevitable, unassailable and normal. Visa’s four-year plan is one such exercise, and once we’ve internalised it, we’ll choose to build their power. We’ll feel strangely comforted by the MasterCard billboard endorsed by the Mayor of London. We’ll find ourselves downloading ApplePay like a dazed child accepting a gift.

So, let’s prepare for the War on Cash. Remember, this is not about romanticising the £10 notes with the Queen. This is about maintaining alternatives to the stifling hygiene of the digital panopticon being constructed to serve the needs of profit-maximising, cost-minimising, customer-monitoring, control-seeking, and behaviour-predicting commercial bureaucrats. And fear not, the Germans are onside, along with the criminals, the homeless, the street-side buskers and an army of people whose lives will never get a five-star rating on a mainstream reputation scoring system. We will forge alliances with purveyors of non-bank alternative currency systems and maintain the option to use our payment cards. Because what we fight for is precisely that. The option.

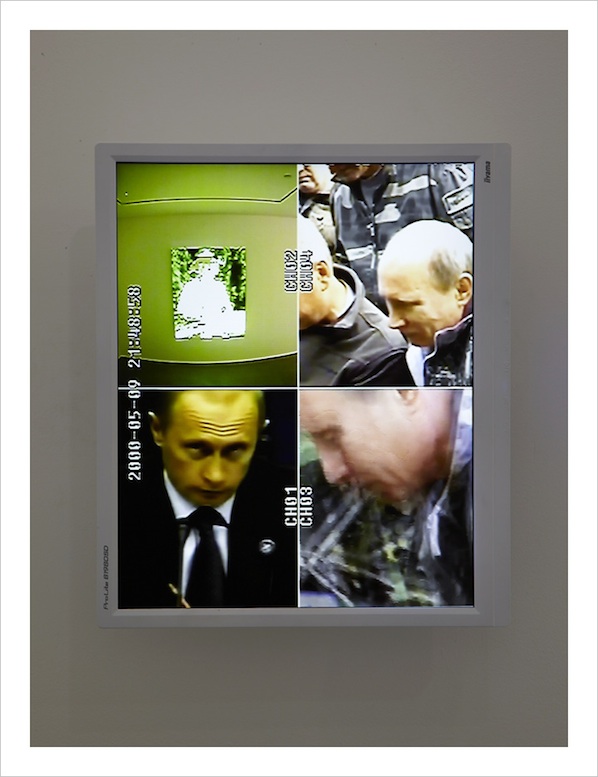

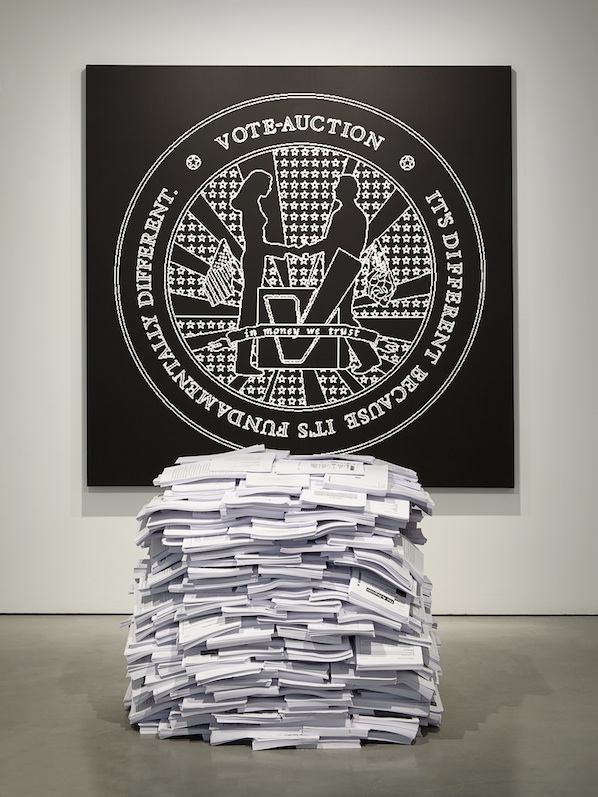

Featured Image: Ubermorgen, “Vote-Auction”, 2000. Installation view from the exhibition “Whistleblower & Vigilantes”

It has been a long time since an exhibition shocked and confused me. In fact, I cannot even remember when it last happened. Yet the exhibition Whistleblowers & Vigilanters has managed to do just that. Curators Inke Arns and Jens Kabisch of the Dortmund art institution Hartware Medienkunst Verein (HMKV) have put up a show in which complete nut cases are presented side by side with political activists, artists and whistleblowers a la Edward Snowden. This makes the exhibition ask for quite some flexibility from the audience. Visitors have to work hard in order to understand the connection made here between, for example, racist conspiracy theories expressed through YouTube videos and the ordeal of a whistleblower like Chelsea Manning.

The very short introduction text to the exhibition guide is part of the puzzle we are presented with. The basic premises of the exhibition are explained in what I think is not the best possible manner, because it leaves out any mentioning or analysis of the huge political differences among the people and works presented. At the same time the use of words like higher law and self-legitimization easily creates a feeling of unease about each practitioner or type of activism in the show:

“The exhibition asks what links hacktivists, whistleblowers and (Internet) vigilantes. What is the legal understanding of these different actors? Do they share certain conceptions? Who speaks and acts for whom and in the capacity of which (higher) law? Among other issues the exhibition will examine the differing legal conceptions and strategies of self-legitimisation put forth by activists, whistleblowers, hackers, online activists and artists to justify their actions.”

By placing the revelations of Edward Snowden next to the complete print out of the manifesto of the Unabomber or (more harmless but still of a different level of impact) the battle over a hostile domain name takeover in Toywar the first impression is a levelling of the practices and people involved. To make some sort of distinction between the various represented rebellious or activist positions in the exhibition guide the whole is divided into sections. The sections however do not indicate socio-political position or relevance, but rather imply the ways people legitimize their actions (1).

The spatial design and mapping of the exhibition seem to give some indication of political direction, but it is accidental. To the far right of the entry we find all installations labeled ‘Vigilantes’: a website collecting images of online fraudsters (419eater.com), two videos about Anders Breivik and Dominic Gagnon’s collection of mostly right-wing extremist YouTube videos. Slightly controversial is how the Vigilantes section puts together these quite obvious nut cases and criminals with Anonymous and what the curators call ‘Lulz’, the near troll-like jokesters who ridicule anything they don’t like with razor sharp memes. I am not sure whether these two products of the online forum 4chan deserve this simple pairing to YouTube hate preachers. A finer distinction between the various Internet underbelly representatives might have been better here. That this could have been done is shown by Lutz Dammbeck’s archive on the Unabomber’s placement in the Vigilante section, which has two labels. It is the sole representative of the Critique of Technology section as well. Another strange pairing happens in the Antinomism section, where an installation around a video with Julian Assange and a rightwing terrorist bomb disguised as soda machine are the only examples.

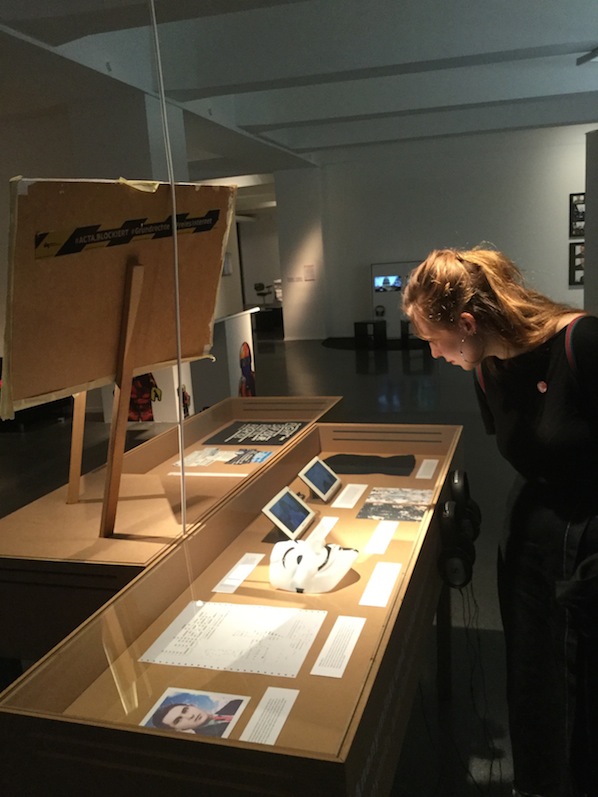

The middle ground of the exhibition shows a mix of artist activism and hacker culture. Mediengruppe Bitnik are here with a video of their Delivery for Mr. Assange. Black Transparency by Metahaven is represented through one utopian architecture model and printed wall cloths. The Peng! Collective’s Intelexit: Call-A-Spy has a telephone stand in the exhibition. The provocative sale of US votes in Vote-Auction by Ubermorgen is here as docu-installation. Etoy’s legendary Toywar is represented as well, with -in my opinion- too small a stand. Traces of many other art works and activist projects are presented in display cases, which give some more background or context to the theme. These were one of my favorite parts of the exhibition, next to the amazingly diligent and meticulous hand-drawn documentation of the Manning trial by Clark Stoeckley.

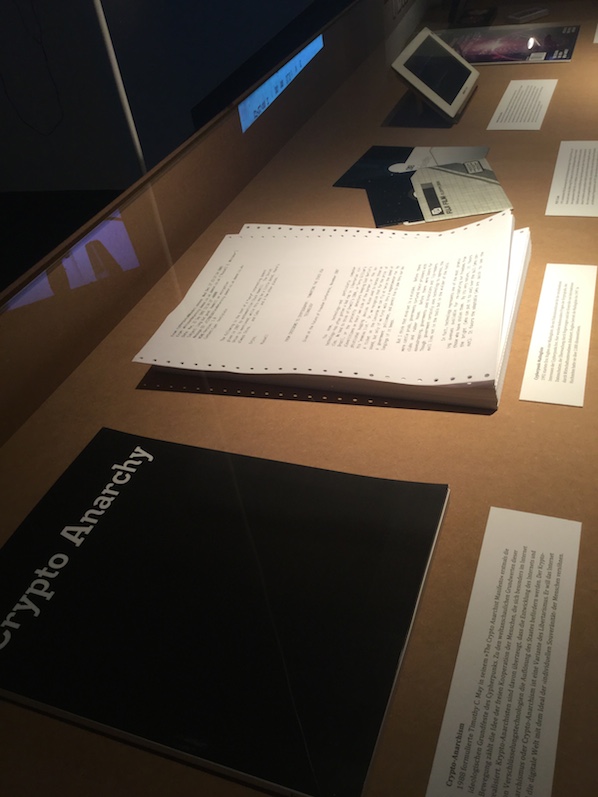

The display cases are dedicated to freedom of speech, tools of online resistance, the Netzpolitik case, anonymity and collective identities and cypherpunk and crypto-anarchism. They provide an important insight into the context within which the other practices in the exhibition exist.

Here we find Luther Blissett, the Italian born collective online identity, with a name borrowed from a former football player. The Blissett identity is related to pre-Internet art practices, in particular Neoism, and has been used for various art pranks and activist projects, particularly in Southern Europe.

Other art projects include the influential book Electronic Civil Disobedience by Critical Art Ensemble, the German hacker art collective Foebud’s battle for free speech and privacy (presented with one of Addie Wagenknecht’s anonymity glasses), and the Electronic Disturbance Theater’s Floodnet. The latter is a DDoS attack software that was used in actions for the Mexican freedom fighters the Zapatistas, by the Yes Men and for Etoy’s Toywar project.

There is also a print out of the Cypherpunk mailinglist. The cypherpunk crypto-anarchist community is responsible for some of the most influential elements of the free Internet. They produced the PGP encryption technology, cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin, TOR, the idea of WIKI and torrent platforms and marketplaces like the Silk Road. Julian Assange was one of its members.

Last but not least the presentation of the Netzpolitik.org case, which covers a German censorship scandal from last year, had to be part of this exhibition. Journalists from the online magazine Netzpolitik were arrested for treason after they had published about classified Internet surveillance plans of the German secret service. A copy of the accusation letter from the state prosecutor is oddly signed with ‘Mit freundlichen Grüßen’ (‘With kind regards’).

All in all the display cases made me happy to see some of the events and works that have been so hugely influential to the development of the Internet (and thus to the development of our current culture and politics) represented in a physical cultural space. They show a side of Internet culture that is heavily underrepresented in the general discourse around new media technologies in both mainstream media and art. During a private tour of Whistleblowers & Vigilantes for visitors of the simultaneously running Hito Steyerl exhibition Inke Arns explained how for her this exhibition is long overdue as well. According to Arns the threat to our freedom through abuse of new technologies should receive as much attention in art as the anthropocene. HMKV sees it as its responsibility to do something about it.

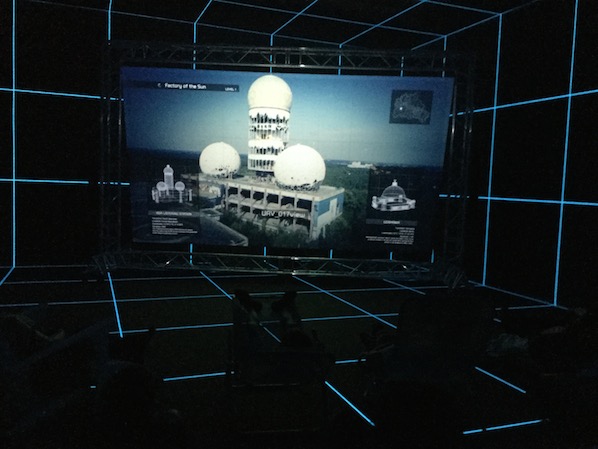

Whistleblowers & Vigilantes however does not make a straightforward statement. Its structure, both physically and content-wise, is too complex for that. This does not mean it is a bad exhibition. The bringing together of the ‘Lulz’, Anonymous, the Unabomber, net art, hacktivism, hackers and Manning, Snowden, Assange and even Breivik in one space definitely creates a lively exhibition, which cannot leave a visitor unaffected. This strange assembly then needs to be unraveled and this is where the curators take quite some risk. The addition of Hito Steyerl’s installation Factory of the Sun, an exhibition that runs simultaneously on a different floor, could help to bring the serious, crazy and light elements of the show together for that part of the audience that loses its way. In her smart playful manner Steyerl blends science fiction, humor and critique of the surveillance society in a faux holodeck cinema experience. The exhibition also includes a few live events that steer the whole into safe waters. Netzpolitik journalist Markus Beckedahl has given a presentation and so has Jens Kabisch. Kabisch wrote a text about whistleblowers that is available on the website, but this text is unfortunately only available in German. My advice to the non-German audience is to download the press kit in order to get more background information.

Whistleblowers & Vigilantes is a challenge to the audience. It asks for more reflection and time to take in than most exhibitions. After getting some more grip on it the complexity and scope of the exhibition, however, is impressive. It not only brings together many important, interesting and sometimes scary examples of contemporary forms of resistance and rebellion. What is also represented is the space of resistance and play that escapes attempts at systematic control, even in a full-on surveillance state. Once recovered from my initial shock this is what stayed with me the most. The wide-ranging documents, objects and installations reveal the system’s shadow spaces and vulnerabilities. Whistleblowers & Vigilanters differs from the flood of other art exhibitions themed around surveillance and control by reflecting on the legitimacy of online autonomous political action in general. Indirectly this means it also reflects upon the space of life that exists beyond all control. Rather than create another horror show around the future of privacy and freedom, with Whistleblower & Vigilanten we are presented with the persistence of fringe cultures and of free thinkers. For me this makes this an exhibition of hope.

Whistleblowers & Vigilantes. Figures of Digital Resistance

HMKV, Dortmund

9/4/16-14/8/16

https://www.hmkv.de/_en/programm/programmpunkte/2016/Ausstellungen/2016_VIGI_Vigilanten.php

https://www.hmkv.de/_pdf/Ausstellungsfuehrer/2016_VIGI_Kurzfuehrer_Web.pdf

Artists to my mind are the real architects of change,

and not the political legislators who implement change after the fact

(William S. Burroughs)

A large-scale model of a CCTV camera made from recycled cardboard peers through the window of the Seventeen Gallery out onto Belmont Street in Aberdeen, alive with passers by. This is the main piece of Under New Moons, We Stand Strong (2016), the project conceived and designed by Teresa Dillon to prompt reflections on solidarity, literacy and symbolism within digital civic governance.

If one gets close enough, it is evident that the eye of this camera is blind for there is no actual watching and recording apparatus inside. Still, the sensation of being watched remains. Bird spikes are mounted on top of the camera. The first thing one notices is the scale of the model: for the first time, what is an almost impalpable and invisible presence (surveillance technologies tend to be increasingly difficult to spot in the urban space) gets amplified, taking a physical presence that invites us to explore our personal relationship with surveillance and the multiple technologies that embody it.

The enlarged cardboard CCTV camera not only reminds passers-by of surveillance, its visual presence, eye to eye and the size of an other, functions to interpellate the viewer as an active gazer. Instead of us being the object of its gaze, the large-scale model allows us to look at the CCTV camera up-front. The exchange of gazes between the two subjects, the surveillance apparatus and ourselves, occurs on an equal level: we occupy a position that is not anymore subservient to the mechanical all-seeing-eye. In the act of looking at the CCTV cardboard model, we can also recognise our own complicit capacity to become overseers.

Teresa Dillon’s installation invites us to become aware of the change occurred in contemporary social and technological developments in the relationship between surveillance and society. This change is subtler than it might appear at first. The Panopticon, Bentham’s prison architecture, was discussed by Foucault in his Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) as an exemplar, among others examined in the book, of the mechanisms of social control that become permanent and interiorised. The prisoners, in fact, have no need to be actually watched, they know that they might be being watched. The condition of being potentially under surveillance transforms the dynamics of the gaze, causing an interiorisation of the watchtower’s gaze, in such a way that the prisoner becomes her own overseer.

Surveillance studies have pointed out how the Foucauldian metaphor of the Panopticon fails to describe the multi-faceted contemporary figurations of surveillance. It is not anymore a matter of keeping the prisoners in a certain space, but much more of keeping them away. The movement from the Panopticon to the Banopticon, for example, exemplifies the attempt to use profiling techniques to determine who should be placed under surveillance for security purposes. The Banopticon can be described as the attempt to keep away certain social groups (asylum seekers, migrants, suspected terrorists) in the context of global security and border control. This ban, interestingly, is not exercised exclusively upon certain groups or in extraordinary circumstances, but also upon those individuals who do not have the resources (for example credit cards and smartphones) to promptly respond to the enticement of consumer spaces such as shopping malls.

We need to take responsibility for the way in which we exercise the power to look. This was the sense of the two talks arranged as part of Urban Knights, a program of events conceived to provoke and promote practical approaches to urban governance and city living by bringing together people who are actively producing alternatives to our given city infrastructures, norms and perceptions. Programmed during the opening of Under New Moons, We Stand Strong, the first talk saw Keith Spiller, a lecturer in criminology at Birmingham City University, discussing state surveillance and individual rights in the context of his practical experiences of accessing CCTV data in London. Heather Morgan, a Research Fellow at the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, presented her on-going research on sousveillance (in the context of health self-monitoring wearable technologies). In the middle of our smart cities, caught up in the illusion of being in control of smart technologies we are actually constructing our own prison.

Dillon’s interventions successfully unfold what the two talks left implicit at theoretical level, that is the passage from Foucauldian surveillance to “surveillant assemblage”. Deleuze’s and Guattari’s concept of surveillant assemblage makes visible processes in which information is first abstracted from human bodies in data flows and then reassembled as “data doubles” (Deleuze and Guattari 1987). Thus, a new type of body is formed, whose flesh is pure information transcending corporeality. The body is an assemblage, comprised of component parts and processes that need to be observed. Moving away from a hierarchical top-down gaze, in a rhizomatic-fashion, surveillance expands in multiple fractured forms.

Going back to Dillon’s installation, on the gallery wall there is a digital print portraying a snowy owl in mid-air flight. This is a special edition print related to an episode on January 3rd, 2016 in Quebec, where a CCTV camera captured a stunning image of a snowy owl in mid-air flight. Four days later the images were tweeted by Quebec’s Transport Minister and went viral, turning the snowy owl into an “Internet star”. In Greek mythology the owl represents or accompanies Athena, the goddess of wisdom – and military strategy. Curiously, the next generation of surveillance technologies developed by the United States military bears the names of Greek mythological creatures. Argus Panoptes, which recalls the all-seeing giant monster with a hundred eyes, is a monitoring system that allows the constant surveillance of a city. Gorgon Stare, an array of nine cameras attached to an aerial drone, takes the name of the monstrous feminine creature whose appearance would turn anyone who laid eyes upon it to stone.

The owl is a highly metaphorical and yet ambiguous presence in the exhibition. On the one hand, the owl symbolises knowledge, wisdom and perspicacity. With its appearance, “flying only with the falling of the dusk” to paraphrase and transpose the famous passage from Hegel where the owl incarnates the appearance of philosophical critique and appraisal, the owl of Minerva (the Roman goddess identified with Athena) makes explicit the ideas and beliefs that drove an era but could not be fully articulated until it was over. Therefore, the owl is revealing something to us about our own epoch – it is our task to decipher the content of the message.

On the other hand, the owl is also the physical medium through which collaborative interspecies strategies of resistant actions to surveillance can be organised. Dillon’s techno-civic intervention, as the artist herself calls her work, is ideally connected to another artistic project, Pigeonblog, made by Beatriz da Costa, artist, academic and activist, member of the Critical Art Ensemble and graduate student of philosopher and science and technology scholar Donna Haraway. Pigeonblog was a grassroots initiative designed to collect and spread information about air quality to the public. Pigeons were equipped with small air pollution sensing devices capable of gathering data on pollution levels. The data could be then visualised and accessed by means of Internet (da Costa and Kavita 2008). Da Costa’s Pigeonblog was inspired by a photograph depicting a technology developed in Germany during wartime but then never implemented: a small camera, carried by a pigeon and set on a timer, was designed to take pictures at regular intervals of time as pigeons flew over specific regions of interest – possibly military targets. Pigeons were participating agents in this early surveillance technology system. Da Costa resuscitated that idea to create a surveillant assemblage formed by a living animal and technology but with civilian and activist goals.

By means of this mythological creature, the owl, Teresa Dillon asks us to learn to look at those technologies of surveillance, to re-adjust our gaze in order to be ready to face them upfront. The role played by mythology is evident not only in the installation but in the procession that accompanied the exhibition on Saturday May 7th. The public were invited to gather together and take part in a “forensic anthropological walk”, as the artist labelled it, throughout the city of Aberdeen, with participants holding hand-held models of two-dimensional CCTV cameras. Stopping in front of the CCTV cameras encountered in Castle Square during the walk, the artist revisited the world history of CCTVs, starting from the first documented use of surveillance cameras in Germany in 1942 for the documentation of Test Stand VII, the V-2 rocket testing facility, through the introduction of CCTVs in the urban landscape in the US in 1968, and more recent examples of surveillance technologies in the UK.

Dillon blends story-telling techniques with an emotional urban cartography created by means of walking together. Namely, the walk cannot be described in the guise of a city tour: the performative element transformed the walk into a procession, a collective rite, consumed on the Aberdeen beach where the paper cameras were set alight by participants. The history of surveillance technologies is in fact interwoven with mythological, symbolic and ritual elements, from the owl to the closing ceremony on the beach. Like in Cities of the Red Night, written by Beat Generation novelist William S. Burroughs, Dillon’s multiple interventions combines history with rituals and performance to evoke magical elements, doomsday scenarios and our phobias about the powers that control and enslave us.

The different interventions conceived and designed by the artist (the artwork itself, the performance, the walking tour through the city, the talks that accompanied the opening of the exhibition) can be read as artistic enactments of the cut-up and fold-in literary technique used to re-arrange and combine the pieces of a text to form new narratives. The technique can be traced back to the Dadaists of the 1920s. It was then popularised by Burroughs in the 1960s as a radical and creative method of socio-political subversion. It is evident that the cut-up and fold-in technique can be applied to contexts other than literature as Dillon demonstrates. It helps overcoming conventional associations (in this case, surveillance as a merely technological apparatus) to create new ones (the literacy infrastructure of surveillance), transforming the reader/player/visitor from a passive consumer of other people’s ideas into the architect of her own knowledge and action.

Under New Moons, We Stand Strong allows citizens to become not only more aware of the technological power infrastructure at work in our cities but also to learn how to read it, confront it, possibly resist it. The beach, at the outskirt of the urban space, a liminal site, nowadays often associated with the refugees crisis, becomes a space of freedom and catharsis. To set the cardboard cameras alight is, simultaneously, an act imbued with mythology – Prometheus’ gift of fire, the first techne, to humankind for their survival – and a collective gesture of transformation and renewal. Having freed ourselves from the idols, from all-seeing eyes, we can stay up-front, together, as a community, to face the darkness of our time.

Seventeen, Art Centre, 17 Belmont St, AB10 1JR, Aberdeen

Supported by Scotland’s Festival of Architecture, Peacock Arts Centre & Aberdeen City Council

Date: Thurs 5 – Sat 28 May 2016

Location: Seventeen, 17 Belmont St, AB10 1JR, Aberdeen

Opening: Thurs, 5 May, 6pm with special edition of Urban Knights

Procession: Sat 7 May, 8pm from Seventeen, 17 Belmont St, AB10 1JR, Aberdeen

Credits

Model & assistance: Jana Barthel

Commissioned by: Festival of Architecture, Scotland, 2016; Peacock

Visual Arts, Aberdeen & Seventeen Gallery, Aberdeen

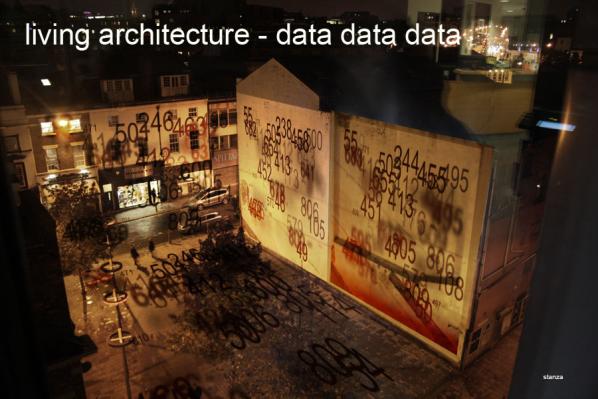

Stanza is an internationally recognised artist who has been exhibiting worldwide since 1984. He has won so many prizes you’d have trouble fitting them all on one mantlepiece. He has exhibited over fifty exhibitions globally and is an expert in arts technology, CCTV, online networks, touch screens, environmental sensors, and interaction. His artworks examine artistic and technical perspectives, within the contexts of architecture, data spaces and online environments.

Recurring themes throughout his career include the urban landscape, surveillance culture, privacy and alienation in the city. Stanza is interested in the patterns we leave behind, and real time networked events, that are usually re-imagined and sourced for information. He uses multiple new technologies so to create distances between real time, multi point perspectives that emphasis a new visual space. The purpose of this is to communicate feelings and emotions that we encounter daily which impact on our lives and which are outside our control.

Much of his work has centered on the idea of the city as a display system and various projects have been made using live data, the use of live data in architectural space, and how it can be made into meaningful representations. See Publicity, Robotica, Sensity, as well as a whole series of work manipulating real time CCTV data to making artworks with them: See, Velocity, Authenticity, Urban Generation. These works reform the data, work with the idea of bringing data from outside into the inside, and then present it back out again in open ended systems where the public is often engaged in or directly embedded in the artwork. Interactive and visually appealing, his style also maintains the substantive power through multi-facetted content.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Stanza: I don’t really get inspiration from the “who” question, I prefer the “what” and “why” questions. As a professional artist I look at loads of art so to understand what art is and can be, and it’s always an ever changing and fluid response. I also spend a lot of time ignoring stuff and material; (focused ignoring) because it has become harder and harder to see though the fog; the noise of it all. Maybe it’s better to think of a working model for inspiration, Andy Warhol had one. Just make the work. That’s what I do. I am not a part time artist in academia or an artist with another job, I’ve done this for the last thirty years, inspired by and in response to the world around me.

This dogmatic commitment to my work comes from my believes that the system you have to trust and invest in yourself. Inspiration, quite literally is everything all around you all at once, all at the same time, moment by moment. This is what inspires my work and it influences the creation of real time information flows, and works in parallel realities. It allows me to stand back at a distance and work with complex data sets while at the same time making meaning from them. Forming data into a shape, because this confluence might inspire a repositioning of thought and values while at the same time unlocking a hidden meaning to enable the viewer to feel and experience something new or to do something creative with the results.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

S: There’s a saying be careful what you wish for. If one reverses this then it could be wish for what you want and need. Influence is problematic because it’s both negative and positive. The idea of influence seems causal, but my own practise isn’t based on influence but in research into certain themes. This enables me to get into both sides of particular questions or debate, so to frame the work I make. Works like these have been inspired by this focus…

The Singing Trees, focus in the invisible things and the environment http://stanza.co.uk/tree/index.html

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

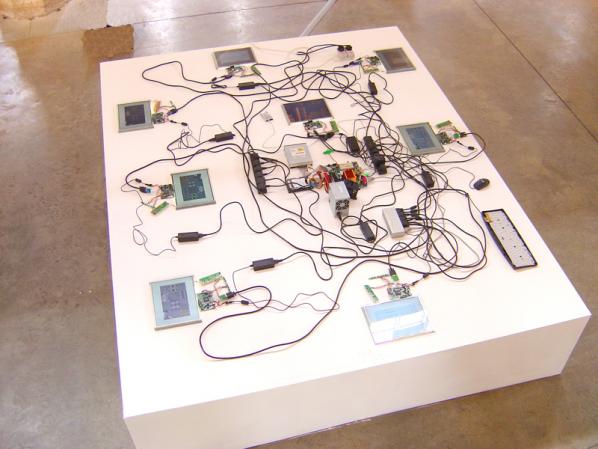

S: I have been researching smart cites, urbanisn, and have collected ‘big data’ since 2004. I have been building my own wireless sensor network. This eventually manifested itself in an artwork called Capacities in 2010 which then influenced all the others in the series until it now has this form.