The global financial dictatorship presents us with a paradox: while the economic transactions capable of shifting the destinies of entire countries are the result of performative language, it is language itself that, in turn, is transformed and subjected by the flows of financial markets. Such a paradox may be understood as a negative feedback loop: a relational process in which one of the actors of the relationship is amplified and expanded (the economy) while the other is weakened and submitted (language). The effects of this paradoxical feedback loop on politics are evident and clear: the linguistic exchange which feeds the public sphere, and therefore the possibility of thinking about the democratic organization of society, diminishes and becomes neutralized because of its submission to the market, up to the point of canceling politics itself. Politics, considered as a space where daily life becomes realized, is reduced to an engine which merely executes the algorithms of finance. In this reconfigured field, the common good becomes increasingly unimaginable as individuals are transformed into cellular automata: inside their bodies, the code of economic behavior and the flat, mutilated language that capitalism requires to operate frictionlessly are already inscribed.

Whoever refuses to enter life as a mere cellular automaton will be annihilated by the financial dictatorship, which is currently passing through an extremely murderous stage: necrocapitalism. Achille Mbembe claimed that the ultimate expression of sovereignty lies broadly in the power and the capacity of deciding who may live and who must die. This was known as necropolitics. Today, the dictatorship of finance prescribes a progressive and quick reduction of the sphere of politics, with the aim of canceling the restrictions that laws and codes used to impose on the flow of capital. And governments have indeed shrunk, turning thus into little more than facilitators of the unstoppable progress of capitalism. However, they have not stopped to exercise their operational capacity to kill and let live. True power has been transferred directly into the hands of capital, who now determines which lives should be halted and which should continue. The power of capital has increasingly turned into a murderous one that, nevertheless, is still executed by the officers of the old sphere of politics.

Mexico passed from necropolitics to necrocapitalism not by force but by the signatures of the presidents and ministers of finance of Mexico, the United States of America and Canada who, in 1992, signed the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). What has happened in Mexico since then? A chaotic chain of privatizations, looting and crime, all of which have been executed with a hitherto unknown intensity thanks to the almost complete destruction of the former sphere of politics.

After the forced disappearance of the 43 students of Ayotzinapa, Elisa Godínez wrote that “it is not surprising that the corporate sector is heading the demands to repress all social protests which directly affect their properties and interests, arguing that the rule of law should be respected.” [1] It is true that, in the post-NAFTA era, such a position comes as no surprise. However, the true novelty lies in the fact that now the Mexican State no longer defends only the interests of national corporations, but also those of multinationals. And this is not a minor novelty: all sorts of extraction industries, for example, have multiplied their concessions and profits thanks to such a defensive stance. And they have done so while devastating lands, ecosystems and people with almost complete impunity. According to data collected by the Red Mexicana de Afectados por la Minería (Mexican Network of Persons Affected by Mining), 450 tons of gold have been extracted from Mexico, a quantity almost three times larger than the 185 tons extracted during Spain’s colonial domination. This unprecedented looting has particularly benefited Canadian and North American companies, who make up almost 85% of all private mining concessions, while paying back a mere 1% of what they extract to the Mexican government [2].

Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution deals with the property of land, water and natural resources. It originally established that “the property of lands and water resources inside the limits of the national territory corresponds to the Nation.” Obviously, this vision had to change radically under necrocapitalism since, instead of recognizing the primordial nature of private property and the right of capitalists to posses it, it indicated that “the Nation” was, in principle, the sole owner. Now, thanks to recent reforms to Article 27, “the Nation” has acquired the right to transfer the dominion over lands and territorial waters (and, consequently, over the humans and non-humans who inhabit them) into private hands. Article 27 is today the red carpet extended by the Mexican State to welcome the financial and linguistic flows and algorithms of necrocapitalism in grand fashion.

The piece “El 27 | The 27th” is an example of what algorithmic politics can be. Far from trying to point to a possible escape from the horror and exploitation of necrocapitalism, algorithmic politics deepens its murderous potential instead. Despite its relative usefulness as a hired murderer, the traditional sphere of politics is terminally ill: it is too old to carry out rapidly and efficiently the demanding tasks of necropolitics. So, once exhaustion has completely died out its powers, politics made by humans will have to be substituted by algorithmic politics, that is: politics made by machines.

In this piece, an algorithm operates directly on the text of Article 27 in the following way: every night, after the activity at the New York Stock exchange has come to an end, a robot obtains its last closing price and its respective percent variation. If the variation is positive, another robot chooses a fragment of Article 27 randomly, translates it into English automatically, and inserts the translation into its corresponding place within the original text written in Spanish. Given enough time, the algorithm will produce a version of Article 27 fully readable in an effective – yet incorrect – English. An automated English that will already have attempted to displace humans brutally, even though they might still be fighting for a territory delimited by language only, and refusing to die. An automated English that will have already eroded a land delimited by language only, rendering it unrecognizable: torn, exploited, almost dead.

“El 27 | The 27th”: http://motorhueso.net/27

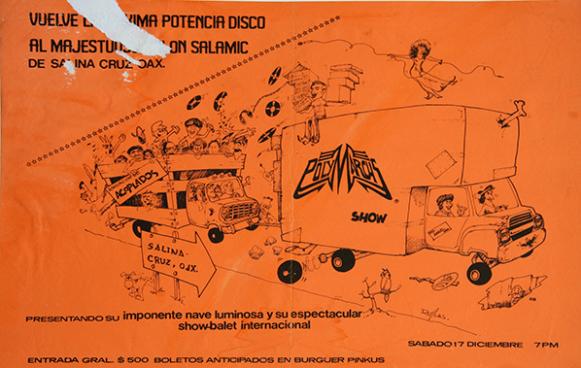

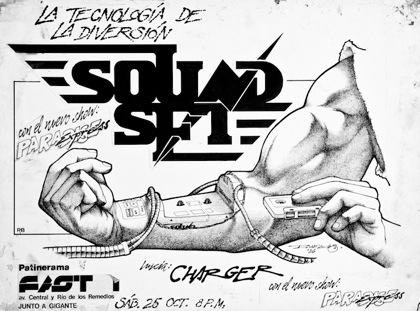

First of 6 articles as part of the Piratbyrån and Friends exhibition at Furtherfield. Mariana Delgado, Coordinator of El Proyecto Sonidero (Mexico), writes about the Polymarchs posters (1980-1990) by Jaime Ruelas. Translation by Tess Wheelwright.

Panther / Jaime Ruelas / Polymarchs. On How We Came To a World of Legend By Mariana Delgado, Coordinator of El Proyecto Sonidero, I met José Luis Lugo in 2009 in the office above the Publicidades Panther print shop in Mexico City. Lupita La Cigarrita introduced us: sonidera, collaborator and number one follower of Sonido La Changa, el Rey de Reyes – the King of Kings. Later we learned from Lupita that José Luis had an important collection of sonidero event posters and flyers. Marco Ramírez, the co-founder of El Proyecto Sonidero, grew enthusiastic.

As soon as we released the book Sonideros en las aceras, véngase la gozadera (roughly Sonideros on the Sidewalks: Bring on the Revelry) in 2012, we began to see what should come next. In 2013 we launched the Proyecto de Gráfica Sonidera, in association with Panther, and in collaboration with draftspeople, poster artists, graphic designers, graffiti writers, sign painters, printers, promoters, collectors and researchers.

We are taken back to the origins of the tropical sonidero movement, which began in the 60s with turntables and LPs – loudspeakers and tweeters set up in the streets, dances thrown in the barrio. Over time various sound systems are added, each with its own crew; soon the multicolored Aztec or robotic lights are streaming. The biggest parties feature close to 50 systems at once, working simultaneously for hundreds of thousands of people. Music is introduced and mixed the Mexican way. Equipment is fiddled with; beats are slowed. Bass rumbles out from walls of speakers. Followers take their places and multiply along with vernacular genres. Transsexual dance clubs form circles on the dance floor; here a family, there a group of insiders – la banda – make their way through the crowd. The mic starts up, amplifying the shout-outs that will circulate the continent on CD and DVD, through streaming, links, posts. From Peñon de los Baños aka Colombia Chiquita to Neza York; from the barrio Tepito aka Puerto Rico to Chimalwaukee, out to all the brothers in Illinois.

In this world, all hatched from La Sonora Matancera. Cumbia and salsa are the queens of a grand court of rhythms. The Virgin of Guadalupe reigns supreme; it’s her congregation. Changó, San Judas Tadeo, and the Santa Muerte share the power thereafter. Epic is important, and family, too. What begins as a passion for Cuba soon builds: music from Colombia, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, the Dominican Republic, Buenos Aires, New York… The sonideros leave behind the established Mexican labels and their standardizing limitations, heading out on their own to comb the continent. They become vinyl diggers, import records, discover bands and musicians; they turn into promoters, create record companies and pirate labels, compile mixtapes to disseminate in the street markets and plazas, at parties and on commercial stands, through the internet.

In the margin within – those more notorious neighborhoods of the Distrito Federal – embroidered logo jackets circulate, lending publicity to the sonidos along with their cards, posters, flyers, banners. Nonetheless, fewer and fewer dance parties are thrown. The city government has issued a discretionary ban of sonidero events in public spaces, canceling even traditional dances like the anniversary celebrations of Tepito’s markets. In the outer margins, ringing the DF and beyond, painted walls announce upcoming events and sonido trailers take over the streets. The dances go on.

We aren’t as familiar with the electronic scene, headed by Polymarchs. Our inroad is through the graphic materials comprising the collection Panther has amassed since 1979, which he rightly considers his primary asset. It all began in the Zona Rosa, where he used to go to trade posters, leaflets, stickers. At thirteen he formed part of the Polymarchs crew, coiling cables. Later he became a publicist, promoter, producer. He never stopped his gathering; stacks of paper tower in the office. Hundreds of posters and dozens of original drawings from the golden age of Hi-NRG pass in front of the camera, as José Luis remembers key scenes and events from this world: when they brought Gloria Gaynor to Mexico for the first time, when Sylvester came, when they packed the World Trade Center.

We are introduced to the world of artists and designers who created an imaginary to suit the precursors of the genre: pharaonic, galactic, utopian, spectacular, and futuristic. Always epic. Tailored to the moment, to the experience of the fans. The posters of the electronic sonidero movement are unique in format, employing unexpected techniques and materials; they are distinct, painstaking, sensational, new. In contrast, the works of tropical sonidos follow in the typographic vein of Mexico’s Gráfica Popular – reminiscent of the wrestling, taking the freedoms of the tropics, whether with box cutter or in full pixel. In the world of disco, Hi-NRG, and techno, the graphics are like the sound system: cult objects, concepts, myth.

“Do you want to meet Jaime Ruelas?” asks José Luis. The master of ink drawing, creator of logos and illustrations as iconic as La Changa or Polymarchs themselves. Of course we do. We are his fans, and we are an army. We arrive nearly punctually to the interview, with photography, audio and video gear in tow. Nearly punctually, because Jaime is already waiting; the son of a watchmaker, he knows machines, design and sound from the inside. He also knows the history of Polymarchs well, and from the beginning. Polymarchs’s first gig took place in his apartment in Tlatelolco. Later, Jaime became the sonido’s first DJ, before switching his focus to images.

Like the sonidos thriving now in the capital, Polymarchs began in Puerto Ángel, on the Oaxaca coast, with a modest set-up – just a single Telefunken console and two baffles. The collective was formed by three siblings in 1975: Apolinar, Elisa and María de los Ángeles Silva Barrera. In 1978 they moved to Mexico City. Apolinar took charge of the sonido, and with Jaime Ruelas he discovered disco and Hi-NRG. The tenacity of Polymarches transcends mere selection of musical genres; the approach here is different. With tropical sonidos, the music, the equipment, the role of DJ and MC are the purview of one person, a single all-powerful figure operating from behind the console. Polymarchs is coming from somewhere else, assembling great towers of scaffolding, creating a spectacle, an experience, an environment. Neither DJ or MC, this is an entire machine. Polymarchs designs, produces and operates structures of light and sound as have never been seen before, radiant vessels that travel, carrying immense tech crews and companies of retro-futuristic dancers, from Tenochtitlan to outer space. There are explosions in the cosmos. On the floor all hands are up, cellphones by the thousands.

When Apolinar Silva and the Polymarchs team arrive at the Centro Cultural de España to give a conference in the context of the Proyecto de Gráfica Sonidera, the auditorium is brimming. Followers sport the distinctive t-shirts and jackets, hold up posters they’ve collected, wave cellphones. Apolinar is glowing; he is the supreme authority and, more than mythic, he is mystic. The audience takes the microphone to share their experiences. Like the time a Polymarchs event was organized in Mexico City’s Zócalo and what people thought was an earthquake turned out to be the earth shuddering under such dance. Below, in one of the exhibition spaces, Polymarchs set up a kind of black-light temple, aglow with, among many others, the visions we now share now with you.

The Proyecto de Gráfica Sonidera was an intensive program that resulted in records and research, specialized workshops and others for children, the painting of walls, the exhibition of graphic, photographic, and video material, and a series of talks along with book and documentary releases. We had the honor of including a drawing by Jaime Ruelas, and we kicked off with a dance party dedicated to Polymarchs… which was epic. There was a little boy who stole the dance floor, winning it against the odds from the more seasoned dancers.

All this was made possible thanks to many people and institutions. Shout-outs to the following generous collaborators: Marco Ramírez, José Luis Lugo, Javier Echavarría, Jaime Ruelas, Livia Radwanski, Mark Powell, Mirjam Wirz, Rocío Montoya, Tonatiuh Cabello, Diego Delgado, Alan Lazalde, Sonido Fajardo, Luis Sánchez, Héctor Rubí, Julio Díaz Corona, Sonido Leo, Christian Cañibe, Eduardo “Aníbal” Dueñas, Eleazar “Canuto” Escobar and the shop personnel of Publicidades Panther, Publicidades Lupano, Aisel Wicab, Citlali López Maldonado, Pedro Sánchez, Marisol Mendoza, Lupita La Cigarrita, Sonido Pío, Víctor Hernández, Edgar Ramírez, Laura Zárate, Griska Ramos, Mirna Roldán. Official respects to FONCA, to CONACULTA, to the Fundación Alumnos 47 and to the Centro Cultural de España.