Featured Image: Stock photography from Google Image search “happy creative tech startup”

Neoliberal Lulz: Constant Dullaart, Femke Herregraven, Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion, and Jennifer Lyn Morone.

Showed at the Carroll/Fletcher Gallery 12 February – 2 April 2016.

Neoliberal Lulz asserts to have born witness, arm-in-arm with rest of us, to an unprecedented shift in the volatility and increasing speculative power of financial markets and the dissolution of value indexing to physical commodities. This relationship has been made particularly palpable in the realization that investment banks and corporations hold a tremendous sway (perhaps even tremendous to an unknowable degree) over our lives. The four artist/groups brought together make work as a way of trying to bring this dynamic into knowing.

Neoliberal Lulz is not so much about this relationship, or the realization of this relationship, between market forces and lived experience. It’s more accurate to say that the exhibition and the artworks contained within it rather serve as a populist blueprint for how individuals can talk to the market. If political economies speak in the limited language of supply and demand, then how can we make ourselves heard?

New media is a particularly good way of addressing this question because of the way hardware and software must constantly negotiate the terms of inter-communication. The success of media is dependent on this trafficking in translations, between file formats, online and IRL, technical apparatuses, outdated and current softwares. So when artists like Constant Dullaart, Femke Herregraven, Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion, and Jennifer Lyn Morone make themselves “corporate,” mimicking the neoliberal virus, this move feels right at home with the kinds of techno-alchemist work being displayed.

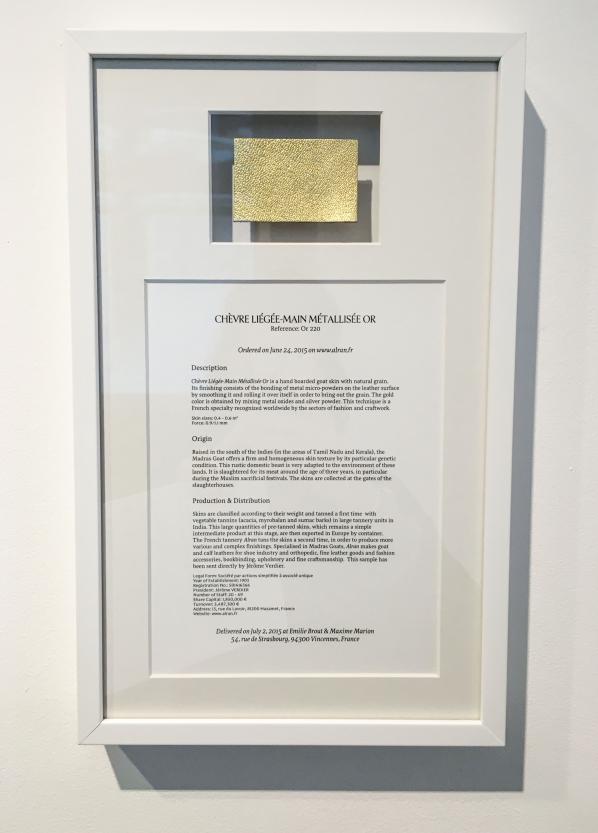

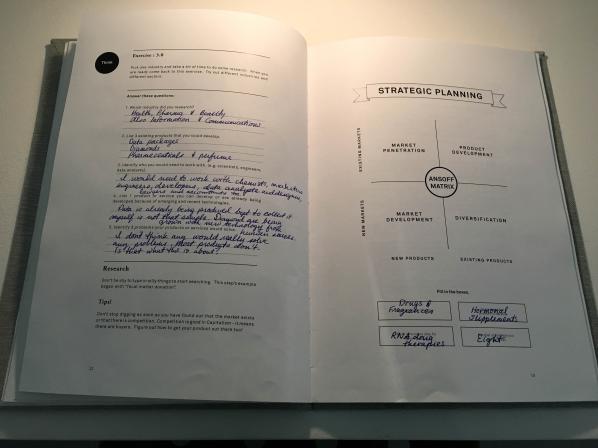

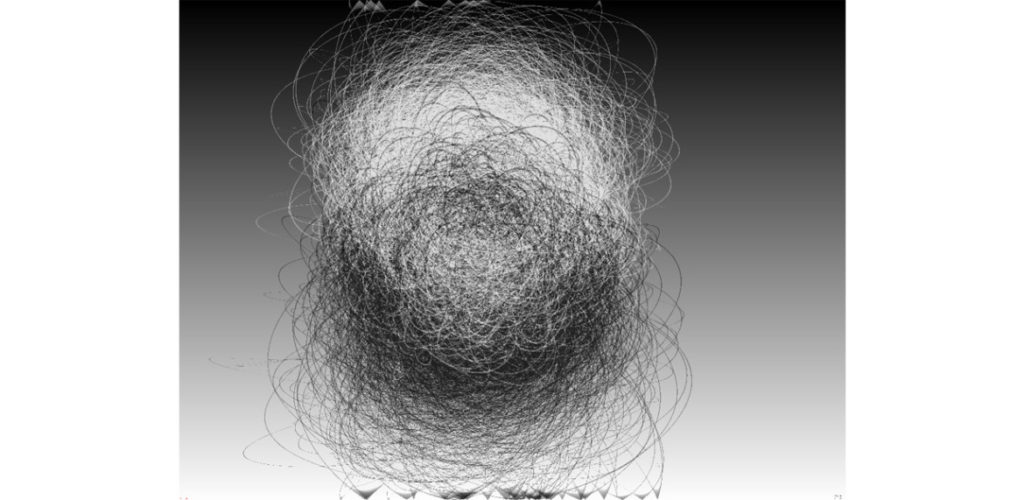

Femke Herregraven makes the mystifying lifespan of high frequency trading material, which feels a lot like spinning straw into gold (or perhaps the other way around). Her works rehearse this slippery, ambivalent relationship between value and objects, indexes and standards. In this way Herregraven’s works ground the exhibition in a similar way as does Constant Dullaart’s Most likely involved in sales of intrusive privacy breaching software and hardware solutions to oppressive governments during so called Arab Spring: by memorliaizing in cold, clunky materiality the “immaterial” processes that are active under the banner of neoliberalism everyday. Three of the four artists on display have incorporated—Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc, Untitled SAS (that’s Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion), and DullTech™ (Constant Dullaart). Between these companies the process of how to become a company is cracked open, revealing how sophomorically simple and complicated the process is, how much paper detritus and nondescript stuff is secreted as byproduct. Constant Dullaart here adds a lesson on the aesthetics of startups with an entire room dedicated to the oddly-familiar B-roll shots of airplanes cut with inspirational platitudes. Jennifer Lyn Morone adopts the the aesthetics of a kind of good life marketing that is gender-targeted, and operates by corroding away what’s already there (mental health, well-being) to make its own market gap.

But I tell you this: the best part of the exhibition isn’t on display. Ask the front desk about buying shares of either Untitled SAS or Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. This is the heart of the exhibition, and it’s either lamentably sidelined or a brilliantly premeditated that just inquiring about the purchase can reveal so many gaps and uncertainties.

When I visited the exhibition, gallery attendants very kindly filled me in on the bold point details of buying shares, to the best of their ability. They explained that Unititled SAS shares sold for €30.00, with a €25.00 admin fee that went straight to Émilie and Maxime. It is not split with the gallery, as often the the sales of an art object are. Was the gallery entitled to any part of the sale of shares of Untitled SAS? Sort of: fifty-percent went to the French government, twenty-five percent went to Émilie and Maxime, and half of the remaining twenty-five percent went to the gallery. Did a new contract have to be drawn up to negotiate the profit negotiations between the gallery and artists who had incorporated some capacity? No, the normal consignment contracts were used (they did not share what the terms of these contracts are; I did not inquire).

What about shares of Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc.— how much did they cost? This was a decidedly trickier question, with nationality and class-based restrictions and allowances. The general gist was that since Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. is registered in the U.S.A., that American citizens are subject to tax; English citizens are not. For English citizens there are also different price points and clauses for lower-income prospective investors. This does not apply to U.S. citizens, who are required to prove salary requirements before purchase can be approved.

Had anyone bought any shares yet, for either company? No.

Eventually, the attendants printed me a Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. Instructions for Prospective Investors document: four-pages single-sided, unceremoniously stapled together. For those unfamiliar with this kind of legalese, it’s a bizarre artifact from another planet. Everyone should ask for a copy.

The title Neoliberal Lulz might tip its hat to the tradition of online trolls and their persistent, agnostic vitriol, but the exhibition itself feels like it sets out some very real stakes. This is a good thing, because an exhibition interrogating the asymmetrical relations of production and profit taking place at a prominent art gallery in Fitrovia (a borough in itself that is paradigmatic of these inequities) could have really been smug, smarmy, shit. The hypocrisy of an exhibition that singularly railed against the unmitigated growth of big business while standing amongst its spoils would be too much. But Neoliberal Lulz is not this: it is far more nuanced in its message, far more unclear on its value judgments. As an art exhibition Neoliberal Lulz did well to espouse the artist-as-researcher model. It helps make sure that the exhibition has legs outside of the exhibition space. The fact that most of these artworks have a life outside of the domain of art, circulating within the very thing they’re critiquing, legitimates their output. The other thing that Neoliberal Lulz does well is not to dwell on the narrative of the disenfranchised. I don’t say this because it’s not important but rather because it just simply wouldn’t read.

Neoliberal Lulz feels like a prompt that comes at a timely moment, slotting in to conversations like this, this, and this. It criticizes at the same time as it offers options, which seems like a rare combination these days. “What is to become of the future for young artists?”–the people wail, lamenting that much of the young, creative elite inevitably ends up siphoned off into the tech startup culture. Neoliberal Lulz seems to say this doesn’t have to be a bad thing, and I’m inclined to agree. All’s not lost when artists adopt an if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em ethos, particularly when they do so with a critical bent. Deeply sardonic and ruthlessly interrogative, Neoliberal Lulz is a successful venture into addressing the malleability of contemporary political economies to more progressive ends.

Carroll/Fletcher Gallery

56-57 Eastcastle St.

London W1W 8EQ

Copyright has been a relevant topic since the development of the printing press. It grants the author the exclusive right to reproduce, publish, and sell the content and form of intellectual property. The copy & paste mentality of the Internet user brought chaos to the system. Blockchain technology should now manage the author and marketing rights in a way that is more transparent, completely free of Bitcoin and monetary background. The idea had its origin in the art scene.

The Internet is a space without horizons or frontiers. It has changed our environment and also, thereby, our sensory perception. In ‘the real world’ we are confronted everywhere by people gazing deeply into smartphones: on the street, on the subway, in airplanes, in queues and cafés. Interpersonal dialogue is increasingly being conducted in the virtual sphere. How does the art scene react to new technological developments in arts? I asked Alain Servais (collector), Wolf Lieser (gallerist) and Aram Bartholl (artist.)

AD: Alain, you are collector of digital art since many years. How actively do you use the Internet and the possibilities that it brings for research into art?

AS: I have the opportunity to generally be able to experience art in the real. This is still an indispensable element in the process of acquiring. I’m a big user of the Internet when it’s a question of looking for information on art that’s of interest to me. The key information I always try to gather before acquiring a work is: – a document collating the works which have marked the evolution of the artist’s practice –a piece of writing by an academic, curator or critic contextualizing the artist’s work – an interview with the artist, as I want to hear his/her ‘ voice’ speaking about on his/her art – and a biography.

AD: Wolf, how much do you use the Internet and its possibilities for better marketing in the art scene?WL: We have a presence on various social media and websites, for example, FB, FLICKR, Bpigs, ArtfactsNet, etc. But we try to limit it to those pages that are relevant to art. As an actual communication medium we primarily use Facebook.

AD: Aram, killyourphone.com provides relief and a critique of technology. What would your subjects be without the Internet?

AB: Despite rising levels of communication across devices and networks, I nonetheless notice how, when friends express their opinions on the social media channels, they do so ever more consciously and selectively. We’ve come to understand that all of the commentary and spontaneous utterances on Twitter, FB & co no longer just disappear, but are saved, analyzed and used. ‘Private is the new public’, said Geraldine Juarez recently. The belief that the net makes the world fantastically democratic and offers an equal chance for everyone has, at least since Snowden’s revelations, been finally buried. To that extent, the theme ‘how would it be without the Internet?’ is very interesting! How could we communicate without central, monitoring services? Which low-tech DIY technologies are available in order to exchange data ‘offline’? How can we live without Google?… (A self-test is strongly recommended).

The interplay between the old and new environments leads to numerous uncertainties and generational conflicts. While some nostalgic digital immigrants still assess the advantages of the digital world as being synthetic, alien and unsocial, to the generation of digital natives, the digital abundance is felt as entirely natural. For them, the new technologies were with them in the cradle.

AD: Alain, you are a digital immigrant. What was the first media work in your collection? When did you buy it and why?

AL: My first experience with digital art was with bitforms gallery in NY, more than 10 years ago – at a time when it was really under the radar. I went to an exhibition by Mark Napier from whom I acquired a work at that time – one of the “Old Testament” pieces. That was very natural for me, because I was looking for some new kind of art. I knew enough of art history to know that every important movement in art was always linked to a social, economical, technological, psychological development in society. It was a time, when I was trying to collect works that were really addicted/connected to the actual world, the world around us. I was thinking, ok let’s put myself in 2150: when I’ll be using my third heart and my second brain, what will I say was important in the year 1999/ 2000? Without any doubt it will be the computer and the Internet 2.0 with Facebook and social networks and everything. Eventually I thought: wow people were creating art and it is digital. I immediately considered it to be a very important development for the arts.

AD: Wolf, you procure and sell digital art. What do you think today is the greatest obstacle to understanding the effect of new media?

WL: The sale and procurement via the Internet leads to superficiality. This is, at least, my perception. Experiencing art on a website, interactively or not, is often characterized by shorter cycles/loops compared to viewing the same website here in the gallery. I think we need, as we always did, a balance between the real and the virtual. And actually, this makes sense, because we ourselves do embody both. It’s a reason why the digital natives often express themselves in analog media – it’s no coincidence!

AD: Aram, your works stand at the charged interface between public and private, online and offline, between technological infatuation and everyday life, whereby you teach us how to better understand our new environment. ‘ Whoever sharpens our perception tends to [be] antisocial …’, said media theorist Marshall McLuhan. Is it true?

AB: Especially TODAY it is more important than ever to sharpen perception with regard to the effects of technological development. Two and a half years after Snowden the public discussion on privacy and mass surveillance continues to level off. While the big secret services use their hefty budgets to snow us under, and to lock the doors to the NSA, the interest in further explosive leaks from the Snowden documents is fading. ‘Nothing to hide’ is the mantra of the ‘Smart New World’, in which we can neither see nor sense the complex mechanisms of surveillance. In contrast to the dystopic Matrix scenario, our world will ever be fluffier, smarter and more comfortable, unless one has the wrong passport or sits on a bus next to a presumed terrorist. Then reality will be brutal. Precisely for these reasons it is so important to make the hidden, abstract data world understandable, whether through concrete images, objects, or installations. If you were to hold 8 volumes with 4.7 million passwords of LinkedIn users in your hand hand, you would suddenly understand the significance of the security of our online identities.

Copyright has been a relevant topic since the development of the printing press. It grants the author the exclusive right to reproduce, publish, and sell the content and form of intellectual property. The copy & paste mentality of the Internet user brought chaos to the system. The blockchain technology should now manage the author and marketing rights in a way that is more transparent, completely free of Bitcoin and monetary background. The idea had its origin in the art scene.

AD: Alain, do you think the further development of the blockchain lead to more transparency and protection against forgery?

AS: I would not use the word forgery, but certainly [against] an unfair use of material or a copyright infringement. I suppose that the blockchain is one path that should be investigated and tested for the copyright protection of online works of art. I believe in a transformation of the economy of the market for online art towards the direction of a wider distribution through, perhaps, a ‘renting’ of the work rather than an illusory acquisition (taking into account the copyright stays with the artist anyway). i-tunes and Spotify both adapted well to the online art economy.

AD: Wolf, do you make use of these new possibilities within the marketing of digital art? And have you already thought about a new currency model?

WL: I’ve already been confronted by this and I think that it makes sense. With my artists though there’s as yet no need or willingness. I’ve yet to engage with new currency models.

AD: Aram, to what extent is the blockchain and Bitcoin really discussed within artist circles?

AB: Services like Wikipedia, the Open-Source Software movement and, in principle, the entire World Wide Web wouldn’t exist at all today had Telco-payment-services pushed through its fee-based BTX/videotext with pay-per-view, in the 1980s. Naturally the possibility turns the never-ending reproduction of classic markets on its head, and in recent years, there have been extensive debates about copyright and intellectual property. We shouldn’t forget though, that a large part of the software that operates the Internet and millions of devices came about in the spirit of the sharing-culture. The blockchain is a powerful tool, which introduces a form of artificial scarcity into the digital environment. It’s up to each artist himself or herself whether and how he or she chooses to distribute their work. The art market and the demand will certainly create some model or other for the sale and distribution of art that only exists in bits and bytes. Let’s wait and see…

Featured image: Zombie Academic haunts the Market of Values

Critical Practice, a group of artists, designers, curators and researchers based at Chelsea College of Art recently organised #TransActing: A Market of Values – a pop-up market made up of over 60 ‘stall holders’ invited to creatively explore and produce alternative economies of value.

During my visit, I first encountered a neo-liberal zombie academic, haunting the market with laments over the demise of an expensive art-education system, which extracts maximum value from students, whilst encouraging them to sell their creativity back to the market. At Becky Early and Bridget Harvey’s ‘Mending for Others’ stall, I was taught to darn, and repaired a hole-ridden Sonia Rykiel hat. Here, mending was framed as ‘giftivism’, a way to build or reinforce a social bond.

At Speakers’ Corner, I heard trade union United Voices of the World represented by Percy Yunganina, one of the #southerbys4. He gave a first-hand account of being banned from site by Sotheby’s auction house for having joined a protest over sick pay and an end to trade union victimisation.

Nick Bell and Fabiane Lee-Perella invited me into Early Lab’s economy of promises, inspired by their work with the Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust: in exchange for a cup of delicately flavoured water, I pledged to make a small intervention to help combat stigmatic preconceptions about mental health.

After these encounters, I #transacted with Critical Practice member Marsha Bradfield, to think about the implications of the Market of Values more deeply:

Charlotte Webb: In critiques of ‘free labour’ on the web, it is claimed that the affective labour of Internet users is exploited by the market. Did you see the Market of Values as a scenario in which the possibility for exploitation was circumvented?

Marsha Bradfield: The short answer is, no. This became acute as building the market ramped up in the days before the event. We became more and more aware how the project embodied our labour, with the vast majority of it being not only unpaid but also affective. We wondered together and apart: To what extent did saying ‘yes’ to the project, sticking with it and honouring our commitment to our peers and community, entail a form of self-exploitation—of us as individuals and as a group? I mean, #TransActing happened and was extraordinary because so many people cared so much—both about the project and each other. And this is, of course, a well-known secret in the worlds of art beyond the art market: their reproduction depends on the widespread exploitation of affective labour. But this isn’t sustainable in the long term. So it’s a valid critique, I think, that #TransActing didn’t exactly buck this trend. Even though we did manage to secure money from the Arts Council and CCW to pay many of those involved, this remuneration was a pittance for what they personally invested. Like others in Critical Practice, I loathe the thought of every transaction being monetised, and in a way this was exactly the conundrum that #TransActing sought to explore by shining a light on types of value that aren’t often valued, precisely because they’re non-financial and cannot easily be accounted for in pounds and pence.

CW: I was intrigued by the uses of the terms ‘value’ and ‘evaluation’ in CP’s description of the event. Are these terms interchangeable for you, or do they carry important nuances? I wondered whether there was something about the measurability of values at stake in the project?

MB: The project was initially called ‘The Market of Evaluation,’ which originated with our research on how value is produced and distributed. We considered, for instance, ‘the value of waste’ by walking around the Isle of Dogs with environmental lawyer Rosie Oliver. She helped us appreciate the social practices of evaluating, well, crap, and how they’re situated, localised and embedded in specific places, buildings, systems, institutions, cultures and histories. The more research we did on evaluation, the more opaque it seemed when generalised. The word has managerial connotations too. So assuming evaluation is, in broad strokes, the assessment of value and that valorisation is the attribution of value, we realised that ‘value’ was the turnkey for our interest. Or rather, it was ‘values’ that so intrigued us, with this plurality opening up space for multiple ones to exist. We also began to appreciate values as transacted through evaluation and valorisation and with this shift, the Market as an event for showcasing these processes gathered steam.

Rather than foregrounding any singular value or type of exploration, our model of distributed curating meant that each Critical Practice member worked with several projects. Each of these explored value in ways that we personally and collectively valued. With 64+ stalls in the market, no one exploration or practitioner dominated. I think we needed this critical mass to make #TransActing a valuable event but not everyone agrees.

Commodification is another way of thinking about the value of #TransActing. The anthropologist David Graeber helped me to crystallise a distinction between value in the singular and values in the plural. David talks about the commoditisation of labour by markets, comparing this with labour like housework and other kinds of care that aren’t commoditised. Of course, it’s money as the so-called universal equivalent that not only allows but entrenches this split. So there’s (singular) value, like that of money that depends on equivalence. And then there are (plural) values, like care, loyalty, generosity, faith, etc. that depend precisely on their refusal to be commensurate with each other.* And so coming back to your question about the measurability of value in #TransActing, Charlotte, I guess that’s the heart of the matter. How do we, on the one hand, take stock of that which must be measured for our work, health, etc. while at the same time more fully appreciate things that can never be measured, but give meaning and significance to our lives?

CW: Critical Practice created bespoke structures for the event, which inevitably created a kind of ‘aesthetic experience’. This brought Claire Bishop’s critique of participatory art to mind – how do you see the role of ‘aesthetics’ playing out in a socially engaged event like this?

MB: You’re right. Tricky questions gather around the aesthetics of social engagement as art practice, especially in the long shadow of the participatory paradigm in contemporary cultural production. Enter politics. As one of many collaborators involved in this project over several years, the ‘aesthetics’ of my engagement has ebbed and flowed over a myriad of micro decisions that together form a kind of slipstream of experience. This makes decision making a prism for organising my insider’s perspective: how I see, hear, and feel this process as it unfolds through sensations of togetherness and shared joy but also tension arising from disagreement.

Much of the decision making that led to #TransActing wasn’t visible on market day. But I’d like to think that ‘aesthetic markers’ maybe signaled it in some way. By these markers I mean indicators that point to the project’s process and all the considerations that it entails. Like the tip of an iceberg, the look and feel of the Market’s stalls, for instance, which were made largely from recycled materials, in collaboration with the stall holders and the art/architectural practice Public Works, pointed to the complex material, conceptual, technical and social processes involved in the Market’s making. I think markers like this help to explain why many who came to #TransActing acknowledged it was ‘a lot of work!’. At the same time the residue of this labour, which filled the atmosphere, gave the impression that doing it was fun.

Decision making was a big part of the participants’ experience too. So many different things were happening simultaneously at the stalls. You had to make moment-by-moment decisions about where to focus. Decision making leading to the market and what occurred on the day seem quite different, though. Much of the will and commitment to make this happen was based on long-term personal relationships. Many of us in Critical Practice are friends and have worked together for years. Exploring the aesthetics of decision making with reference to these tight ties and in contrast to the looser ones organising the experience of #Transacting as a one-day event strikes me as a revealing way to tap the complexity of socially engaged art as cultural production.

*For a concise discussion of theories of value in anthropology, see David Grabber, ‘It is value that brings universes together’ HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3, 2 (2013): 219-43.

——–

Critical Practice is: Metod Blejec, Marsha Bradfield, Cinzia Cremona, Neil Cummings, Neil Farnan, Angela Hodgson-Teal, Karem Ibrahim, Catherine Long, Amy McDonnell, Claire Mokrauer-Madden, Eva Sajovic, Kuba Szreder, Sissu Tarka and many more besides.

www.criticalpracticechelsea.org

criticalpracticeinfo@gmail.com

Charlotte Webb: @otheragent

Marsha Bradfield: @marshabradfield

Leave your money at home and use your personal data to buy, sell, or barter for a delicious range of commodity experiences at the MoCC Free Market. Local residents, park visitors, and online participants are invited to share how they value shopping and trading, in the street, and on their devices. In doing so, you’ll be helping us to develop a radical new artwork for exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery in September 2015. Come along to Finsbury Park and find out more.

Entrance is free on production of a MoCC loyalty card, available on arrival.

Watch out for the MoCC Roaming Marketeer to claim your reward vouchers.

Follow the event @moccofficial and find out more about online involvement.

This event is part of the research and development process for Museum of Contemporary Commodities, MoCC produced in partnership with Furtherfield, and supported by Islington Council, All Change Arts, ESRC and University of Exeter.

Add your valued commodities to Museum of Contemporary Commodities and help us test out our interaction prototype.Warm up with a Virtual Shopping trip, where you can map and discuss your trade and exchange habits with family, friends and strangers. Find out detailed information on the provenance, materials and trade-justice issues contained within your chosen commodity through a Live Chat with our expert Commodity Consultants. Upload your commodity to the MoCC database, and help curate MoCC in Finsbury Park.

A volunteer-cooked free meal, from the Edible Landscapes PACT kitchen, near to the Manor House gate. Trade your data for a free delivery of your meal, or organise your own pickup free of charge. www.ediblelandscapeslondon.org.uk (Friday only)

Discover your future through the Forebuy service. We will scientifically predict your next most urgent desire and discover in real time which affordable and amazing product is ready and waiting for you. Stop by and discover unexpected treasures from Finsbury Park surroundings whilst chatting about needs and algorithms.

Use LEGO re-creations to turn your data and commodity stories into animated gifs, whilst sharing your experiences of local trade and exchange with Finsbury Park locals.

A 3 day event for all the family to draw, make and play online games for the future of the park for the health and prosperity of all…or for total catastrophe. It’s all about the future these days. So take a drawing challenge and imagine a different future. Share your vision and see it turned into free online games to play, remix and share. Developed by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Dr Mary Flanagan (Tiltfactor) www.playyourplace.co.uk

Ever fancied your having your portrait drawn by a street artist? Go one better with our hacked scanner. A truly individualised datafication process, and a great souvenir of the Free Market! Our hacked scanner was built with advice from artist Nathaniel Stern. The stall is being run by Furtherfield artist in residence Carlos Armendariz and Amelia Suchcika. Read more here.

Browse the most up-to-date recordings, release your own records and walk away with limited edition thickear art tapes. No need to bring anything except your personal details – thickear Records Store is a one-stop-swap-shop for exploring current models of currency and exchange. An ongoing series of participation, performance and installation artworks about public transaction, which investigate economies of data exchange and consider how transactions are employed to create value. www.thickear.org

Take a quiz! Match your shopping habits to our detailed guidelines and share your results with your social network.