On 28th October 2011, I travelled to Sète in the South of France to see and review Annie Abrahams’ show Training for a Better World.

The first of two reviews (the second will be somewhat longer and in an academic journal later this year) is now available on DVblog.

What was particularly pleasing about going to the press view and then staying on for the opening proper was the opportunity to engage with the work over quite a long period – some four hours.

About halfway through the evening, I started both photographing and sketching as aides-memoire for my reviews, but I soon began to enjoy the feeling of responding to the work for its own sake, and I began to think about presenting the drawings and photographs (plus some drawings made from the photos two days later, as well as a couple of manipulated photos) as a kind of photo-essay/derivative work.

MADE REAL

an exhibition by Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern, the founders of Wikipedia Art.

Networks – social, political, physical and digital – are a defining feature of contemporary life, yet their forms and operations often go unseen and unnoticed. For this exhibition, Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern, artists and co-founders of Wikipedia Art, take these networks as their artistic materials and play spaces to create artworks about love, power-play and a new social reality.

Three works are shown for the first time in the UK: Wikipedia Art, a collaborative work “made” of dialogue and social activity; Given Time, an Internet artwork that creates a feedback loop across virtual and actual space; and Playing Duchamp, a one-on-one meeting and game between an absent artist and viewer/participant.

Free admission to exhibitions and events.

Wikipedia Art by Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern

‘if you claim something to be true and enough people agree with you, it becomes true.’ Steve Colbert on Wikiality

‘I now pronounce Wikipedia Art … It’s alive! Alive!’ Kildall and Stern

Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern famously used Wikipedia as an artistic platform, creating a collaborative project that explores and challenges our understanding of how knowledge is formed and disseminated. For over a year, they planned the initiation of Wikipedia Art, a socially generated artwork that exploits a feedback loop in Wikipedia’s citation mechanism. Here, a “word war” across blogs, interviews and the mainstream press, which involved Wikipedians, artists, journalists, lawyers and even the Wikimedia Foundation itself, continuously defined and transformed a work of art in much the same way that these categories define the discourses of the everyday.

‘We ask our potential collaborators – online communities of bloggers, artists and instigators – to exploit the shortcomings of the Wiki through performance.’ Kildall and Stern

(Often unwitting) collaborators ‘performed’ the work through a debate about its aesthetic, conceptual and legal legitimacy in over 300 texts in over 15 languages on the Internet via blogs and forums such as Rhizome and Slashdot and in the press, including the Wall Street Journal and the Guardian UK.

This exhibition charts the inception, birth, life, death and resurrection of Wikipedia Art, which questions the authoritative role of Wikipedia. It reveals its fallibility whilst debating the control of access to and knowledge creation.

Wikipedia Art featured in the Internet Pavilion of the Venice Biennale 2009. In 2011 it was an awarded finalist at the Transmediale festival in Berlin.

Given Time by Nathaniel Stern

Furtherfield presents Stern’s polar projections of Second Life lovers. Second life is a 3D simulated and virtual world inhabited daily by thousands of people around the globe. To access Second Life, you must embody an avatar (a virtual human representation of yourself), seeing what they see through a computer screen. Stern places his lovers and us in a feedback loop between virtual and actual space.

In Given Time, two life-sized and hand-drawn avatars simultaneously stare longingly across their virtual pond and the real-world gallery floor. They hover in mid-air, almost completely still, supported by the gentle sounds of their breath, the wind blowing, and birds in the far-off distance. The viewer is both the observer and participant of this reciprocal relationship. Through the bodies and eyes of another, we see, look and are seen. Stern says: “Here, an intimate exchange between dual, virtual bodies is transformed into a public meditation on human relationships, bodily mortality, and time’s inevitable flow.”

Given Time was partly supported by the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee and produced with the help of Jo-Anne Green and Bryan Cera.

Playing Duchamp by Scott Kildall

The American artist Scott Kildall, exhibiting for the first time in the UK, has fused the two worlds of art and chess in a homage to Marcel Duchamp, a chess master and artist recognised for shifting the paradigm of conceptual art. Using the recorded matches of Duchamp’s 72 tournament games, Kildall has modified an open-source chess engine to play chess as if it were Marcel Duchamp. By sitting down to this game of computer chess, visitors interact with the ghost of Marcel Duchamp, whose love for chess rivalled his attraction to art. Playing Duchamp is a 2010 New Radio and Performing Arts, Inc. commission for its Turbulence website.

Furtherfield invites you to come and play because, as Duchamp said: “The creative act is not performed by the artists alone”.

Playing Duchamp is a 2010 New Radio and Performing Arts, Inc. commission for its Turbulence website.

Going the distance for fine dining with global friends

In June, Furtherfield will host two telematic dinner parties to accompany this exhibition to create a co-presence dining experience with our remote friends mediated by digital technologies (network connections, projections, laptops and sonified objects). As food is the greatest mediator, we aspire to a satisfying remote connection through the frame of the dining experience.

Contact ale[at]furtherfield[dot]org for details on becoming a dinner guest.

Scott Kildall

Scott Kildall is a cross-disciplinary artist working with video, installation, prints, sculpture and performance. He gathers material from the public realm to perform interventions into various concepts of space.

Scott has a Bachelor of Arts in Political Philosophy from Brown University and a Master of Fine Arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago through the Art & Technology Studies Department. He has exhibited his work internationally in galleries and museums and received fellowships, awards and residencies from organisations, including the Kala Art Institute, The Banff Centre for the Arts, Turbulence.org and Eyebeam Art + Technology Center.

Scott is a founding member of Second Front — Second Life’s first performance art group. He is an artist-in-residence at Recology San Francisco. He currently resides in San Francisco.

More information: www.kildall.com

Nathaniel Stern

Nathaniel Stern (USA / South Africa) is an experimental installation and video artist, net.artist, printmaker and writer. He has produced and collaborated on projects ranging from interactive and immersive environments, mixed reality art and multimedia physical theatre performances to digital and traditional printmaking, concrete sculpture and slam poetry.

Nathaniel has held solo exhibitions at the Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johnson Museum of Art, Museum of Wisconsin Art, University of the Witwatersrand, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and several commercial and experimental galleries throughout the US, South Africa and Europe. His work has been shown internationally at festivals, galleries and museums, including the Venice Biennale, Sydney Museum of Contemporary Art, International Symposium for Electronic Art, Transmediale, South African National Gallery, International Print Center New York, Milwaukee Art Museum and more. He is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art and Design at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee.

More information: http://nathanielstern.com

Download Wikipedia Art: Citation as Performative Act (Creative Commons licensed)

by Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern, to be included as a chapter in ’ Wikipedia: Critical Point of View. Eds. Geert Lovink and Nathaniel Tkacz. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures (University of Amsterdam), 2011. Forthcoming. Print.

Furtherfield, Unit A2, Arena Design Centre, 71 Ashfield Rd, London N4 1NY, +44 (0) 2088022827

Free admission to exhibitions and events -contact Alessandra Scapin ale[at]furtherfield[dot]org

Brian Eno hovered over me in a darkened room as I squatted writing notes about his 77 Million Paintings on a crumpled up piece of paper. Though I knew he couldn’t see what I was scribbling, its not often one gets the chance to come face-to-face, or rather back-to-face in situ with the flesh and blood incarnation of one’s investigations. He had slipped into the viewing room at the Glenbow Museum unobtrusively because he likes to watch – the audience as well as his “paintings,” and therein lays his strategy and appeal. In a lecture he gave that night at the Museum auditorium he described, in magnificent pantomime, the reactions one has when entering the viewing space of his exhibit:

looking around, furtively glancing at the work

walking further into the space, looking around, glancing at the work

leaning against the wall, glancing at the work

squatting, glancing at the work

sitting down, glancing at the work

focusing on the work, lying down on the floor mesmerized by the work

unable to tear oneself away from the work

77 Million Paintings contains 550 paintings Eno created over a span of 22 years. Since 2006 the exhibit has toured all over the world including Tokyo, Sydney and St. Petersburg before landing in Calgary. The digital projection is a “generative” work in that the ambient music for which Eno is better known, and the combination of images are generated and combined in an endless mandala-like array by a computer. Nine screens project a diamond shape with eight inserted “paintings” and one solid colored square on the lower right hand side serves as a control for the other eight. There are four black leather couches for people to zone out on while enveloped by his signature ambient sounds – and they are packed to capacity as the audience warms and hunkers down to the slow experience.

Originally conceived for in-home viewing, the show seems to change your brain waves from Alpha to Beta to Theta and the experience is pure occipital enjoyment. The cross-fades in the banks of images creep up as the landscape subtly changes as blue morphs into green, and triangles expand into circles As Eno says, “We’re not seeing a film. There’s no beginning, there’s no progression, there’s no end, there’s no narrative, there’s no drama. In fact everything is missing that would normally be called art or entertainment.”

Eno’s lecture at the Glenbow Auditorium could have continued all night but for the protestations of those with day jobs. He began explaining the radical impact Copernicus had in 1543 when he revealed man was no longer the center of the universe, as earth orbited around a system with some 400 million stars. Darwin came along in 1859, and pointed to the phylogenic tree stating there were 20 billion species besides humans. “ We are amazingly minute in this picture,” Eno mused. After Darwin it was Cybernetics, which introduced the notion of feedback as a way to think about complex systems. We cannot control these systems, only set them up to control themselves, and that notion became part of his vocabulary of how things organize themselves.

Starting with royal Kings and the Church, man organized himself in hierarchies from the top down that includes the structure of the 18th Century orchestra, still extant today. Sixty or seventy years ago this would show up in the shape of a top-down pyramid, but the world now functions more as a feedback loop, not a hierarchy. Eno explained when he was growing up his uncle slipped him a book on the artist Mondrian. He found the pictures magical, economical, and transparent. They contained “no subterfuge of technique.” Attending art school at Winchester School of Art, part of a music school in England, his forward thinking art professors invited the composers John Cage, Christian Wolf and Morton Feldman to lecture. Not one musician or music student on campus came to hear them.

He described listening to Terry Riley’s minimalist music composition In C,as “life changing.” That piece contains 53 short, numbered musical phrases lasting from half a beat to 32 beats repeated an arbitrary number of times. He also mentioned Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain, where Reich recorded Brother William, a Pentecostal preacher and “sought to maintain the fascination of the speech content while intensifying its meaning and melody through rhythm.” This piece Eno admitted, “is the basis of most of my career.” He said one’s ears function differently than one’s eyes. Eyes scan all the time. If they don’t scan, they habituate and don’t see any thing. If you have a repetitive event the eyes cease to see, and what he focuses on is the uncommon information, “the out of phase collision of the loops.” This approach makes your brain do the composing. As this he says, has led him to his work ethos, “doing as much as I can with as little as possible.”

—-

Brian Eno’s exhibition 77 Million Paintings takes place in the Glenbow Museum from January 6 to March 20 2011. http://www.glenbow.org/exhibitions/

Private View: Friday 25 February, 6.30-9 pm with Live Performance by Garrett Lynch

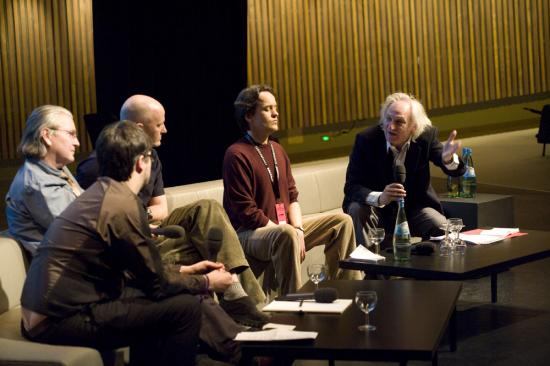

Special guests on the night: Dr Richard Barbrook, Andy Cameron, Garrett Lynch, Quayola, and Eleonora Oreggia, aka XNAME.

REFF- Remix the World, Reinvent Reality! from Furtherfield on Vimeo.

Directly from Italy, Art is Open Source, and FakePress presents REFF a Fake Cultural Institution to launch, promote and distribute its Augmented Reality (AR) Drug to reinvent reality. Visit the exhibition to discover the effects of three innovative molecules created by the REFF chemical lab: REMIXine, REINVENTum, and REALITene.

REMIXINE

The REMIXine compound is an innovative molecule that forms a fundamental ingredient in all our drugs. The molecule powerfully reacts with others, disconnecting their predetermined bonds and allowing the core elements of other compounds to reassemble, forming entirely new ones in complete freedom. REMIXine augments the total entropy of systems, and it is a known stimulator of creative processes acting for the systematic creation of insights into the world.

REINVENTUM

REINVENTum compounds collaborate with the other molecules found in our drugs to reassemble components into new forms once their bonds have been disassembled. REINVENTum affects the equilibrium of neural ecosystems, as it can effectively activate the neurotransmitters which control human forms of expression: this action has profound impacts on the areas of the brain that engage language and memory, allowing the rapid formation of entire networks of new symbols.

REALITene

REALITene is an unstable compound. Its complex molecule self-arranges into virtually infinite configurations. Furthermore, different patients have been known to react to different molecule configurations at different times in their clinical life.

Also, explore MACME, the new open publishing tool at the exhibition, encounter the artworks and performances, and enjoy the freedom of access and expression. In other words…take the REFF AR Drug.

This exhibition showcases a live glitch performance, an urban intervention and a virtual entity by artists featured in the new REFF book: Garrett Lynch (Ir), Rebar Group (US) and xname (It) alongside a real-time interactive map that describes the life of REFF all over the world: 60 authors, artists, designers, architects, hackers, journalists, activists; dozens of actions; a live and real-time stream of information collectively produced by a worldwide community of re-inventors.

The REFF map on the exhibition is available online from the opening date: http://reff.romaeuropa.org. The mapping process is open: please contact us if you feel that your actions are reinventing reality and, thus, should be added to the visualization.

For more about Art is Open Source and Fake Press

www.romaeuropa.org

www.fakepress.it

www.artisopensource.net

Trav–erse – Live performance by Garrett Lynch

Exploring radio waves on a world band analogue radio, the performance should be perceived as both a linear and non-linear journey progressively moving through the sonic space of broadcast wireless networks and the physical geographies and cultural spaces they both represent and permeate.

The performance traverses and returns across a radio band, a technological interface, along linear trajectories. Sounds with no correlation between their representation on this band and their ‘actual’ location will be captured, layered, reworked, and transformed within new media to create a cultural and social sonic dérive where all spaces exist simultaneously.

Garrett Lynch (IRL) is an artist, lecturer, curator and theorist. His work deals with networks (in their most open sense) within an artistic context; the spaces between the artist, artworks and audience as a means, site and context for artistic initiation, creation and discourse. Recently most active in live performance, Garrett’s practice covers net.art, installation, performance and writing.

PARKcycle by Rebar Group

The PARKcycle is a human-powered open space distribution system designed for agile movement within the existing auto-centric urban infrastructure.

While its physical dimensions synchronize with the automotive “softscape” of lane stripes and metered stalls, the PARKcycle effectively re-programs the urban hardscape by delivering massive quantities of green open space—up to 4,320 square foot minutes of park per stop—thus temporarily reframing the right-of-way as green space, not just a car space.

Using a plug-and-play approach, the PARKcycle provides open space benefits to neighbourhoods that need it, when they need it, as soon as it is parked.

Built-in collaboration with the kinetic sculptor Ruben Margolin at his studio in Emeryville, California, the PARKcycle made its debut on PARK(ing) Day 2007 in San Francisco.

PARKcycle was made possible by a grant from the Black Rock Arts Foundation.

REBAR is an interdisciplinary art and design studio based in San Francisco. Rebar has created public art interventions and design projects around the globe. Rebar remixes the ordinary repurposes the ubiquitous, and restructures the fabric of the urban environment by exposing hidden assumptions and shared meanings embedded in the everyday experience of the built world.

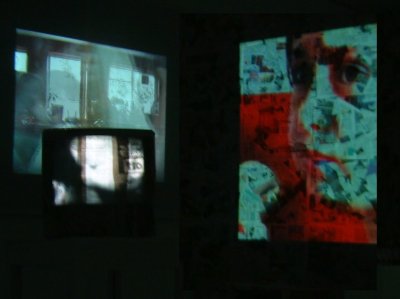

Virtual Entity by XNAME

Virtual Entity is a research project and net-art work trying to redefine the concepts of authenticity, ownership, uniqueness and seriality within the digital domain. The practical aspect of this speculation is a simple application developed to create (and edit) the soul of a file. This is a metaphor: the soul, a text-based soul, is the place where it is written who or what a certain entity is; it is a mark for preserving identity.

This software, proposing a single answer to the questions raised by the practices of licensing and cataloguing digital files, is transforming the traditional approach towards metadata and digital property. The main idea is that any file is an independent creation living its own life and experiencing various levels of transformation and progressive generation (of meaning, shape, and entities) in the course of its virtual existence. The main focus points are the relations (semantic or genetic) among files and the processes of fragmentation, multiplication and transmutation of the cultural units composing them.

Virtual Entity constructs in parallel a theoretical mythical world and its functional technical counterpart; its ultimate shape (and visualization) is that of a monster, a bodyless entity composed of souls and formed by the structure of their relations – and the history of digital data starts drawing itself.

Virtual Entity is displayed for the first time as an installation at Furtherfield Gallery in London. The work takes the form of a tryptic. The central projection shows the command line application soul, the left monitor displays the web application souls, while the right monitor displays the virtual entity monster, a real-time representation of the database performed by live coding software Fluxus.

Virtual Entity Alpha is prototype software. Its main new features are URL support, macosx install, web application, Fluxus visualisation. This software was designed by xname and coded by xname, megabug, Antonios Galanopoulos and Gabor Papp.

Events at Furtherfield Gallery

Opening event: 25 February 2011, 6.30-9pm

Live Performance by Garrett Lynch at 7.30pm

Special programme by REFF the Fake Institution

Open call to Remix the World! Reinvent Reality

The REFF map on the exhibition is available online from the opening date: http://reff.romaeuropa.org. The mapping process is open: please contact us if you feel that your actions are reinventing reality and, thus, should be added to the visualization. http://www.furtherfield.org/contact

REFF Youth Programme

A special task force was required to ensure the immediate diffusion of the REFF AR Drug to the younger generations. Perhaps surprisingly, the Fake Institution agenda has inspired approval and enthusiasm in the academic world. In the two weeks before the exhibition FakePress, together with Art is Open Source, is running a series of workshops and presentations across universities and to groups of students in and around London to remix the world: Southbank University, Goldsmiths, Writtle College, University of Westminster, Queen Mary University.

Please contact us if you’d like to participate or organise further workshops/presentations http://www.furtherfield.org/contact

More information about student workshops.

Please visit AOS website to learn more about what happened during the REFF workshops

MACME, an open source tool for cross-medial publishing

Created by FakePress, MACME is new a cross-media, multi-author content management system, that enables the creation of multi-device and paper publications, featuring location- based technologies, QR-codes, and augmented reality .

The platform will be released for the first time during the days of the exhibition, under a GPL3 Licence, as a real policy for access promoted by the REFF.

Student movements in Italy/UK

”The use of communication technologies and invasive practices for reinvention reality is crucial for student movements in this difficult moment. We would like to get the students involved in the REFF experiments by providing access to those technologies that can work as effective forms of critical and alternative communication. Students in the UK and in Italy will have access to all the cross-medial CMS used to build the REFF book, which will enable them to create their own QRCodes and Fiducial markers that they can then stick around the city to disseminate information integrated within their communication across the web and the city.” – Art is Open Source.

During the exhibition run, students will also be invited to curate their own event in which they can present their take on the idea of “reinvention of reality”, and connect with the students’ movements in other countries (using Skype at Furtherfield, at the ESC in Rome and at the Cantiere in Milan) presenting themselves to each other. The event will terminate with an urban performance in which each party exchanges and prints QRCodes stickers that are then disseminated across the city.

More about Art is Open Source

AOS operates interdisciplinarily across universities and research institutes, businesses and associations, critical collectives and extreme practitioners in arts and design, promoting innovative approaches to the environment, to (multi)cultural interaction, and to the creation of real, sustainable and socially responsible opportunities.

More about REFF

REFF started by investigating themes around intellectual property and cultural policies and then expanded to the domains of freedom of expression and the idea that the tactical use of technologies and network-oriented practices can enable people to change the rules of the game and reinvent our reality. Taking inspiration from street arts, raves, skateboarding, and technologies allow us to re-code and write onto the world, creating layers of additional reality that express our own interpretation of the cities we live in, of the things we buy and use every day.

One project outcome is a book published in 2010, which will soon be available in English. The book is a cross-medial publication enacting the theories investigated by FakePress (a next-step publishing house created by AOS in 2009 researching the REFF themes through the idea of reinventing publishing itself): it is simultaneously a book; a location-based, augmented reality application; a living digital ecosystem; and a wide tagging mechanism using QRCodes and Fiducial Markers to disseminate content and interactions on objects, architectures and spaces.

The book was created using a series of technological tools to maximise accessibility to these critical tactical technologies. The tools have been arranged into a platform called MACME (Multi Author Cross Medial Ecosystem) that has just been released under a GPL3 licensing scheme. The release of these and further technologies is an integral part of the work of net.art, which informs the REFF project.

For more information:

http://www.artisopensource.net

http://www.romaeuropa.org/

http://www.fakepress.it/

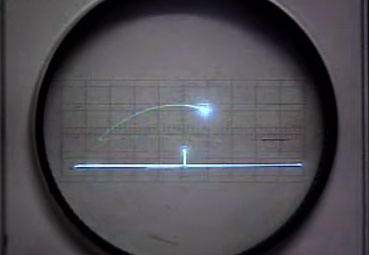

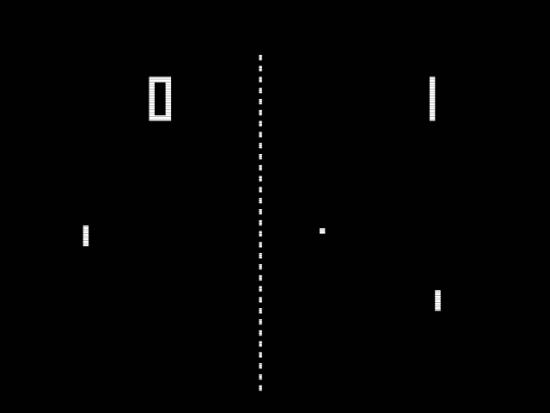

Classic video games such as Pong, Tetris, Space Invaders, Pac Man and Super Mario have in the past decade inspired many artists in their work. The common link between all of these games is that they are very easy to learn and play. There is no need for manuals, just a few simple instructions on the screen. The graphics are simple, the colours few, the characters and style are pixelated. These games have influenced a whole generation and have over time become a part of our cultural heritage. Even today, these games still amuse and fascinate players and have also inspired various artists to use them in their art. In a series of articles, we will look at some classic games and give examples of how they have been used in art and what impact they have made on the art scene. First out is PONG.

It was the American physicist William Higinbotham who in 1958 created what many consider to be the first computer game. The game was called “Tennis for Two” and was played on an oscilloscope with help of a simple analogue control.

Click here to view video on Youtube…

It took, however, until 1972, when the Atari Company, founded by Allan Alcorn and Nolan Bushnell, picked up the idea and created a commercial version and called it PONG, before the game became one of the first real big sellers for the computer games industry. PONG is a simple, minimalistic game that consists of two rectangles and a square, which symbolize two tennis racquets and a ball. You can either play against another opponent or against the computer. In this simplified version of tennis, the goal is to hit the ball so the opponent misses it.

PONG is probably the videogame that has inspired most artists over the past decade. When the Computer Games Museum in Berlin in 2007 organized a major exhibition entitled “pong.mythos” over 30 artists attended with works of art inspired by PONG. The catalogue explains why PONG fascinated so many artists: “No other video game has been the origin of artistic production quite as often as the simple black-and-white tennis game. In addition to its popularity, it seems to be this minimalism that especially appeals to artists, since the playing pattern is a virtual prototype of the essence of each and every communication situation: the ball as the smallest possible unit of information, oscillating between sender and receiver” (from the catalogue “pong.mythos” 2006).

The artist group /////////fur//// showed their “Pain Station” (2001) in which the player who missed the ball were punished with physical pain, a blow on the hand, heat or an electric shock. “Pain Station” connects the physical world with the virtual and the virtual player’s mistakes turn actual real pain.

The artist group Blinkenlights working in the urban environment was represented with a project that transformed a large office building at Berlin Alexanderplatz to a digital screen where passersby could play PONG on the facade with the help of their mobile phones. In the artists S. Hanig and G. Savicic’s work “BioPong” (2005) the ball was replaced with a living cockroach where the players would try to push the insect over to the other side. And in the group Time’s Up version “Sonic Body Pong” (2006) the ball in the game was only a sound which the players could hear in their headphones and with help of large green rectangles on their heads they would try to hit the sound from the ball.

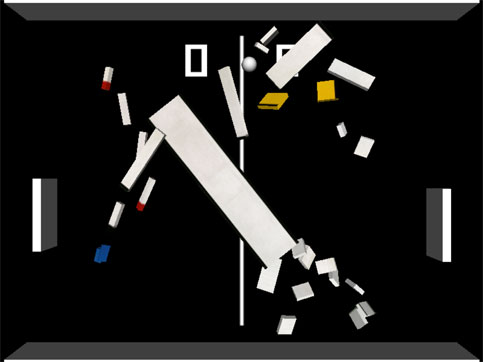

There are also many other examples that were not included in the exhibition “pong.mythos”. As early as 1999, the artist Natalie Bookchin made “The Intruder”, a work where PONG was one of 10 different videogames that she used to create an interactive artwork by Jorge Louis Borges short story “The Intruder”. The Danish artist Anders Visti mixed the game PONG with the art of Piet Mondrian in “PONGdrian v1.0” from 2007. The playing field in Vistis artwork reminiscent a painting by Mondrian but when the ball hits the fields it disturbs the lines and colour fields, and creating new opportunities and challenges for the player. Finally, I can mention the Swiss artist Guillaume Reymond, who has made a series of performances called “Game Over”. In a theatre auditorium, he creates animated sequences by using real people in colourful T-shirts, where each individual represents a square on a screen. By moving the people in the auditorium, he can create short video sequences, for example of PONG playing in the lounge.

The reason that PONG is so popular among artists is that it is one of the very first video games, and therefore there is a large identification factor and a strong relationships between the game, the player and the artwork. PONG is also one of the easiest games in terms of both appearance and to learn to play, which paradoxically makes it so easy to transform and use in different contexts. The phrase “less is more” seems in this case a good explanation why PONG has inspired so many artists in recent years.

Pong Mythos – http://pong-mythos.net/index.php?lg=en

Natahalie Bookchin – The Intruder http://bookchin.net/intruder/

Guillaume Reymond – Game Over http://www.notsonoisy.com/gameover/

Anders Visti – PONGdrian v1.0 http://www.andersvisti.com/arkiv_grafik/pongdrian.html

HTTP Gallery is pleased to host the UK premiere of In the Long Run (2010), the new work by art collective IOCOSE, produced by Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art (Ljubljana) as part of the platform RE:akt!.

View short Trailer of video on Youtube

In the Long Run (2010) is a reconstruction of a possible future high profile media event. The death of pop star Madonna is described in a BBC News special edition, with a journalist and studio guest who go over the details of the fatal car accident, the statements of the VIPs and the reactions of fans around the world.

It is not a true story, but neither is it improbable. All TV networks prepare obituaries about famous people to put on air in the event of an unexpected death. The death of an international figure is not just predictable, it is actually predicted in the video files kept up to date in their archives.

The new video will be accompanied by two previous works, Doughboys (2009), a ‘real time mockumentary’, following a trio of real-life super heroes who defended illegal issues in the police patrolled streets of Rome, and FloppyTrip (2009), an installation consisting in a kit, to prepare your own hallucinogenic drink by recycling redundant floppy disks and provided with a video explaining how to use it.

IOCOSE has been working in Italy and Europe since 2006. It organises actions in order to subvert ideologies, practices and processes of identification and production of meanings. It uses pranks and hoaxes as tactical means, as joyful and sound tools. IOCOSE thinks about the streets, Internet and word of mouth as a battlefield. Tactics such as mimesis and trickery are used to lead and delude the audience into a semantic pitfall.

IOCOSE will be interviewed live on Furtherfield on Resonance FM on Wednesday 03 November at 7pm. Available to download from www.furtherfield.org/resonancefm.php

To accompany In the Long Run, we are pleased to present a new essay by critic, writer and curator Domenico Quaranta about IOCOSE’s new work. (download PDF)

Production: Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana, 2010 www.Aksioma.org Project produced as part of the platform RE:akt!

Also screening at:

RE:akt! – Reconstruction, Re-enactment, Re-reporting

Rotovz Exhibition Salon, Maribor, Slovenia

21 October – 19 November 2010

More Information:

IOCOSE: www.iocose.org

RE:akt!: www.reakt.org

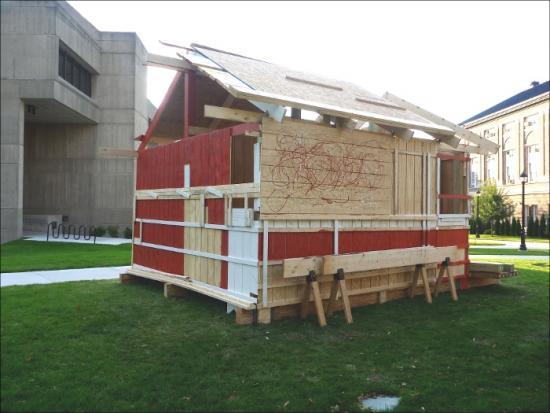

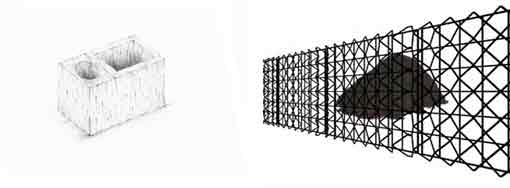

All Raise This Barn – a group-assembled public building and/or sculpture.

“Artists MTAA are conducting an old-fashioned barn-raising using high-tech techniques. The general public group-decides design, architectural, structural and aesthetic choices using a commercially-available barn-making kit as the starting point.” -MTAA

Eric Dymond: Could you give me a brief history of MTAA?

T.Whid: Mike Sarff (M.River of MTAA) and I met in college at the Columbus College of Art & Design in Columbus, OH. We both separately moved to NYC in 1992 and started collaborating as MTAA in 1996 first on paintings and then moving on to public happenings and web/net art. We’ve been collaborating since, showing our work via our websites at mteww.com and mtaa.net. We’ve earned grants and commissions from Creative Capital, Rhizome.org and SFMOMA and shown at the New Museum, 01SJ Biennial, the Whitney Museum and Postmasters Gallery.

ED: The All Raise This Barn project uses one community to design and another to construct. Barn raising is itself a communal activity, drawing out the best in people and providing a place of sustenance for the Barn owner. How did you come to use a Barn Raising as the central performance subject?

M.River: From the start, Tim and I have been interested in how groups and individuals communicate. How do we speak to each other? What rules do we use? How does communication fail or how can it be disrupted? What is the desire that engines (TW: controls?) all of this – and so on. This interest in exchange is what attracted us to the Internet as a site for art in the beginning.

Along with communication as text, speech or image, we like to use group-building as a method for working with non-verbal communication. We’ve built robot costumes, car models, aliens and snowmen with large and small groups. It’s a type of building that is intuitive and open to creative improvisation. This kind of intuitive building is heightened by placing a time constraint on the performance. In the end it’s not about the end object, which we always seem to like, but more about the group activity.

So, at some point we began to think how large can we do this? A barn-raising seemed like the next level. It’s bigger than human scale and contains a history of group-building. Barns also have a history of being social spaces. Your home is your world but the barn is your dance hall.

ED: Did you envision it as a community event from the beginning?

MR: Yes. An online community, a physical community and a community that overlaps the two.

ED: It’s a hybrid work that draws upon some important conceptual precedents. The instructional aspect takes Lewitt and turns the strict instructions he uses upside down by allowing online decisions to drive the design. Did you find the responses to the online polling surprising?

MR: Yes and no. Like the other vote works we have produced, Tim and I set up how the polls are worded and run. So, even though we try to keep the process as open as possible, the nature of how people interact is somewhat fenced in. Even with a fence, people will find a way to move in strange directions or break the fence. It’s not that we think of the surprising answers as the goal of the work, but it is an important part of the process.

ED: There is also the performance aspect which I find exciting. The performance from both events are well documented. Were there any concerns regarding the transfer of the polls instructions to physical space?

MR: We had the good fortune of doing the work in two sections. When Steve Dietz commissioned ARTBarn (West) for the 01SJ Out of the Garage exhibition, we spoke about the sculpture as a working prototype for how a large pile of lumber could be group-assembled in a day with direction from Internet polling. From this prototype we then had a model for how to go about ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC.

Tim and I had a few loose ground rules on how to approach the translation. One was that we would leave some things open to the interpretation of the crew. Another was that both Tim and I had our favorite poll questions that we tended to focus on. It was impossible to do everything as some polls conflicted with other but some details liked ghosts, dripped paint and open walls seemed to call out to us.

Kathleen Forde, who commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC, spoke about these details as where the work became more than the sculpture. The small details held the whole process – material, design polls, and performance together.

ED: I think this comment on the details is right. On first glance there is a fun, open appeal to the work. But when you look at the overall project and how the different phases are tied together it becomes really complicated in the mind of the spectator. There are also different definitions of spectator in this work. The spectator who answers the poll, the spectator on the net who is grazing through the documentation, the ones who engage in the physical construction and those who witness the completed barn. It’s not a simple piece when we perform a detailed overview. Did you think about the various types of spectator that would spin off the project? Were the possible roles for the spectator considered after the fact or were they part of the planned concept?

MR: The “ideal spectator” thought first came up for us in a project called Endnode (aka Printer Tree) in 2002. For this work, we built a large plywood Franken-tree with a set of printers in the branches and a computer in the trunk. We then built a list-serve for the tree as well as subscribed it to a few list-serves. When people communicated with the tree, the text was printed out in the exhibition space. At first we talked about the ideal viewer as one who communicated with it online and then saw that communication in the physical space or vice versa.

Now I feel that the ideal spectator hierarchy is not as important and possibly limiting. Each experience should be whole as well as point to the larger aspects of the work. People can come in and out of the work on different levels. You voted. You followed the performance documentation. Are you missing an experience if you did not build with us or see the results? Yes, an activity is missed. Can you experience that activity thorough documentation. Somewhat. Are you going to have a better understanding of the work. Probably not. Even for me, some aspect of the work will not be experienced. In Troy, they are programing it as a meeting place now that is it is built.. When they are done with it, they will dismantle it and rebuild it elsewhere as a work space.

I say all this even though it is interesting to me that a work can move in and out of levels of viewer experience. I’m not sure as to the draw of it yet but I do not feel it is about an cumulative effect.

TW: Since Endnode I’ve always liked the idea of an art work that exists in multiple (but overlapping) spaces with multiple (but overlapping) audiences. With our pieces Endnode, ARTBarn and Automatic For The People: () there are 3 distinct (but overlapping) audiences: the online audience, the audience in the physical space and the (select few member) audience that experiences the entire thing.

ED: It’s that opening of possibilities that makes this ultimately a networked piece on many different levels. I find the idea of two barns, a few thousand miles apart yet linked by common purpose really intriguing. I’m talking about the whole set of experiences, not just the physical space of the barn. There’s a collapse of Geographic distance for the community and a richer experience because of that. Was the project conceived as two distinct locations or was that a fortunate turn of events?

MR: Fortune. Kathleen Forde, commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC then Steve Dietz commissioned the beta version for the 01SJ “Out of the Garage ” exhibition. Everyone liked the idea of the work arching across time and location. We all also liked the idea that the materials would be reclaimed after it stopped being a sculpture. For me, the reclaimation of the materials to use for a functional structure is the final step of the work.

ED: As the final step, the reclamation removes the common space where the community currently shares the sculpture. Does this mean you are going to use the online documentation as the artifact, coming full circle to where the piece began? Is it important to you that the communal memory will share this role?

TW: Yes, the documentation is the artifact. The barn structure or sculpture itself had been conceived as being physically temporary from the beginning.

ED: Thanks to both of you for your time and for this work.

‘Living’ is the result of a six month residency at the V&A by Christian Kerrigan – from January to June 2010 – and it is part of The 200 Year Continuum. The 200 Year Continuum is the title of a project by the same artist that explores the relationship between nature and technology. Interestingly ‘Living’ was exhibited in the same space where it was created: in the digital studio of the V&A. This was a small room with dim light and crowded with rarities. It felt like one was penetrating the secretive and magical space of experimentation of some sort of mad professor.

Once in the space my gaze wandered around a series of oddities. On the right, a table full of raw materials; in the middle of the room, a fish tank with algae floating in high pH waters; on a wall, a real time video projection showing the evolution of the algae; on a different wall, a slide projection showing some drawings; in some shelves, notebooks with notes by the artist; above the sink, chemical products piled up on a shelf; and on each and every window a semi-transparent drawing. No explanations, no titles, nothing. It’s you and the objects. Luckily Christian Kerrigan was always about, meeting visitors and discussing the work. We started looking at the materials on the table. Christian told us those were unprocessed rocks and crystals that he used as the starting point for his drawings. He scanned pieces of amber, moss, fiber glass, volcanic rock or resin and produced a model using 3D software. Then he manipulated that model to create his drawings and printed them on semitransparent paper. He eventually placed them on the windows of the space. This routine allowed him to explore the different stages of a process that makes real matter and virtual space intermingled. It is a practice that explores where the process of creation begins, and what it does to reality. ”The drawings, he tells us, become extensions of the physical material which I started with.” Although we have become accustomed to discuss the hybridity of our nature-culture, the way Christian carefully interwove materialities and virtualities was very evocative. The fact that the drawings were placed on the windows gave yet another layer of complexity to the mixture. The colours of the printings morphed natural light into a hybrid light turning the atmosphere of the room into a creative and ongoing process.

Next I wondered about that mysterious fish tank in the middle of the room where algae lived (and died) in high pH waters: Encased Nature. Apparently the algae reacted to the elevated pH creating a protective coat that eventually killed them. At the bottom of the tank: a graveyard of coated dead algae showed the consequences. I instantly loved the idea. Again an experiment about the hybridity of natural and controlled habitats. I thought it was a particularly dystopic illustration of the environment we inhabit where control works on the conditions of the environment, dictating the way reality unfolds. This is an emerging tendency in our most-discussed societies of control, what has come to be called soft control. And we could take it even further, and see it as a great illustration of today’s climate of fear. In such a habitat, the threat has become virtual and all-pervasive, it has become poisonous in itself, just like high pH. The nightmare of security measures that this artificially produced environment justifies links quite well to the ‘lethal-protective’ coat. What this allegory leaves out, though, is the power of imagination! The capacity of conditions to be turned around, the potential for intervention and deviation from the pre-programmed chain of (re)actions. The idea of projecting a live video recording on the wall was to intensify the experience and highlight the importance of mediation. As Christian argued, we are now more used to experience nature through a lens than to experience its presence. However, the quality of the footage seemed to work against the intentions of the artist and rather than intensifying the experience of that enclosed nature, it tended to obscure it. The particular texture that the webcam gave to the recordings turned that hybrid habitat almost into an abstract movie. On a different corner there was another video projection made out of a series of drawings. Interestingly they had been created using a ‘living technology’ and recorded at a nano-scale. For Living Drawing, the artist had collaborated with Martin Hanczyc from the Department of Physics and Chemistry at the University of Southern Denmark. They had manipulated some protocells that inhabited chemical gradients and reacted to ultraviolet light. When UV light was applied to the fiberglass where these protocells ‘lived’ their motion left traces of colour that were recorded. This technique, although still in its early stages, allowed the artist to ”explore the spontaneous event of drawing by using organic systems”, he told us. Kerrigan’s rather cryptic exhibition proved to be an inspiring and very personal exploration of the blurring between nature and culture in its absolute physicality. Paying particular attention to the materiality of the creative process, from the composition of the materials used, to the chemistry of the drawing process or to the laws of electromagnetism that inform light in its interaction with his work, his methodologies show a passion for unfolding reality in its many scales. His work is that of someone who’s starting to explore rather than someone who’s making an assertion; it is tentative rather than conclusive, it is interesting for its questions rather than its answers. However, even if sometimes vague, it is at points pleasingly dark and sometimes inspiringly intense.

Introduction:

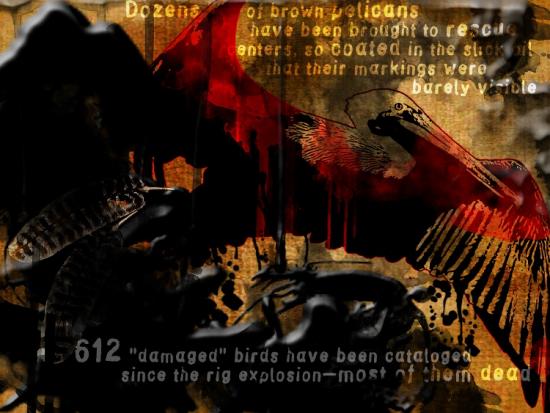

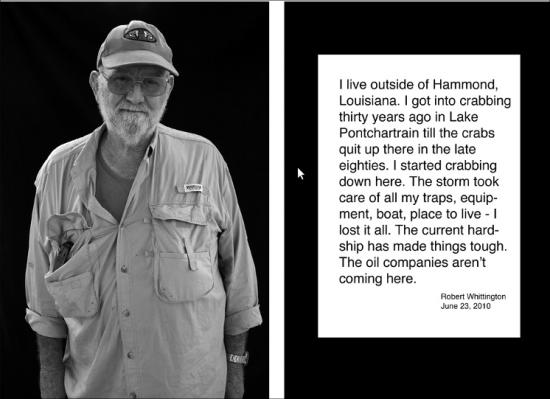

As media attention wanes, the impact of British Petroleum’s Deep Horizon, off-shore drilling disaster continues to unfold. Artists worldwide respond to this new ecological catastrophe in a group show organized by Transnational Temps, an arts collective exploring the interstices of art, ecology and technology. For Andy Deck, one of the founding members of Transnational Temps and the curator of the show, “After a decidedly unsuccessful round of climate negotiations in Copenhagen, the disaster in the Gulf of Mexico frames this exhibition of Earth Art for the 21st Century.”

Now hidden from view by BP’s media campaigns and other de facto censoring actions, the images of oil-covered birds struggling to breathe and fly, oil and dispersant-coated fish, dolphins and whales washing up dead while most sink to the ocean floor, have all but vanished. Partially filling the void are the artists showing here who are recreating topographies: mapping the course of a deadly shadow over our shores and waters; and reinterpreting the sea, its rising levels and largesse, before the vicissitudes of man and nature. Transnational Temps.

———-

Spill >> Forward by Transnational Temps describes itself as an Online Exhibition. It is a website containing images and other media on the theme of oil spills. Some of the images were shown at the MediaNoche gallery from July 30th – November 19th, 2010, with works added or removed so it isn’t just an online catalogue of a meatspace show.

The front page of the site warns that you’ll need a browser that supports HTML5 video and audio, and states that you can view it using patent-free media codecs. From a Free Software and Free Culture point of view this is excellent, your ability to view the art is not restricted by anyone else’s technological or legal machinations. This is also good from an artistic point of view. The software used to view the art can be run and maintained by anyone, making it more accessible, exhibitable and archivable. But this freedom doesn’t extend into the work itself. some of the art uses proprietary software, and none is under a free Creative Commons licence.

The image on the front page, or possibly the image exhibited at the entrance to the exhibition, is not advanced HTML5 video or canvas tag animation but an animated GIF. A Muybridge-ish series of still images of a pelican in flight flickers rapidly up and down as it descends behind an iridescent oil slick that solarizes the bottom half of the image. It’s an effective image in itself, a visually and net.art-historically literate statement that also serves to set the stage for the rest of the show.

This is clearly a politically motivated exhibition, with the theme of the exhibited art centred on a specific historical event (the Deepwater Horizon disaster). Oil spill and petrol station imagery dominates . The resulting art varies from cooly ironic asethetics (Ubermorgen), photo and video journalism (Guillermo Hermosilla Cruzat, S.Slavick & Andrew E.Johnson, Chris Dascher, Adrian Madrid), agitprop (Eric Benson, Geoffrey Michael Krawczyk, Alyce Santoro, Russ Ritell, Terri Garland, Patrick Mathieu), photography(Jessica Eik, Sabina Anton Cardenal), painting(Jessie Mann), collage(Ume Remembers), performance art(Graham Bell), interactive multimedia (Gavin Baily, Tom Corby, Jonathan Mackenzie, Chris Basmajian, Matusa Barros, Mark Cooley), augmented reality (Mark Skwarek and Joseph Hocking) and drawing (Cristine Osuna Migueles, Adrienne Klein, Jesus Andres, Sereal Designers) to video and audio art (Irad Lee, Luke Munn, Gene Gort, Tim Geers, Gratuitous Art Films, Alex George, Collette Broeders, Fred Adam and Veronica Perales, Virginia Gonzalez, Henry Gwiazda, Maria-Gracia Donoso, Jeremy Newman).

This is a lot to take in but the diversity of the work is a strength rather than a weakness, building a broad and visceral response to the Deepwater disaster. Verbal responses to the disaster from politicians seem unconvincingly nationalistic and corporate in comparison. It might seem hypocritical for artists to criticise the source of the energy that feeds us and allows us to make new media art. But we are trapped in that system, and we must be free to criticise it.

Politically inspired artworks have a difficult history, tending to be either bad politics or bad art. The art in Spill >> Forward is excellent, though. Some has a more direct message than others. Again the diversity of the exhibition plays a positive role here. The immediacy of the agitprop images doesn’t need art historical baggage to be effective, but that immediacy provides a social context for the more contemplative or abstract works. The more contemplative or abstract works don’t hammer home a simple political message but they provide an aesthetic context for the more direct images. They work very well together.

Some of the pieces in the show are clearly illustrations or recordings of work, some are electronic media that can be played on a computer, some are clearly designed to be experienced specifically through a computer system. If you removed the political theme of the show it would still be a visually (and audially) and conceptually rich cross-section of contemporary art. I was going to write “digital art” there but the show includes painting, drawing, performance, and other analogue or offline media recorded digitally for presentation online. The celestial jukebox is hungry.

If I had to pick out just a few pieces from the show I’d say that I was struck by the sounds of Luke Munn’s Deepwater Suite, by the visuals of Ubermorgen’s DEEPHORIZON, by the monochrome images and text of Terri Garland’s photography, by the video mash-up of Colette Broeders’ Breathe and by the critical camp of Graham Bell’s Radical Ecology. I think my favourite is Mark Skwarek and Joseph Hocking’s “The Leak in Your Home Town”, an iPhone app that uses the BP logo as an Augmented Reality marker to super-impose a 3D animation of the Deepwater leak over live video of your local BP petrol station. It is art that could only be made now, technologically, aesthetically and socially.

The aesthetic and conceptual competence of the artistic responses to the environmental and human crises of the oil spills in Spill >> Forward make the case for art still being a relevant and capable answer to society’s need to make sense of unfolding events. Art can still provide a much-needed space for reflection, and Spill >> Forward creates just such a space in a very contemporary way.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Decode: Digital Design Sensations

The Victoria and Albert museum, London

8 December 2009 – 11 April 2010

Decode: Digital Design Sensations at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) brings the state of the art in art computing to a venerable cultural institution. Everything from the posters and banners around town to the hoardings on the entrance to the gallery containing the show makes it clear that Decode is a serious cultural event. It’s a spectacle, a dark space alongside the well-lit galleries of the V&A, drawing you in with points of light and distant sounds. The crowds are reassuring for the popularity of art computing yet disconcerting for the experience of the art at times.

Don’t forget to ask for a catalogue as you hand over your ticket on the way in. The sponsor’s foreword should raise a smile to anyone familiar with the software industry, but the introductory essay (which only occasionally becomes the latest casualty of the confusion that the word “open” shows), the details of works in the show and the interviews with Golan Levin and Daniel Rozin are all very informative. The catalogue also draws attention to Karsten Schmidt’s specially commissioned graphic identity for the show, which can be downloaded and modified as Free Software.

The show is divided into three sections. Generative art, data visualisation, and interactive multimedia (or, as the catalogue puts it – Code, Network and Interactivity).

The generative artworks suffer in comparison to the other pieces by being mostly small-scale screen based pieces. However appealing the images are on the screen (and they are) they cannot compete with the projections and three dimensional installations of the other sections. With the exception of an interactive version of the video to Radiohead’s House of Cards by James Frost and Aaron Koblin, the work does not refer to the human figure or to the viewer, another feature of many of the most popular pieces in the other sections. And apart from Matt Pyke’s typographic totem pole, my other favourite piece of the section, the work is calm. Beautiful, but calm. It would reward prolonged contemplation in a quieter environment and might benefit from presentation on a larger scale to better bring out its aesthetic qualities. But this is not that environment, and that presentation is not given to the work here.

The data visualisation section has more projections and custom hardware, and also has more human interest. The emotion of We Feel Fine by Jonathan Harris and Sep Kamvar, the surveillance state expose of Stanza’s Sensity, CCTV assemblages, Make-Out, the porn-inspired kissing figures of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and the social data visualizations of Social Collider by Sascha Pohflepp & Karsten Schmidt are sometimes less visually sophisticated than some of the generative pieces, but address current social and technological developments more directly. The world wide web is twenty years old, it has drawn in the mass media and media feeds from the real world, and many of its users produce and encounter gigabytes of data over time. Representing and exploring that technological and cultural environment is something that art can do and that art is particulalry well placed to do given the importance of the aesthetics of interfacing and visualisation to the contemporary web.

The interactive multimedia section contained the real crowd pleasers of the show, although some of the pieces had “out of order” notices on them when I visited. Yoke’s virtual reality Dandelion Clock controlled by a hairdryer, Ross Phillips’s Videogrid, a physically interactive group portrait and Daniel Rozin’s Weave Mirror, a cybernetic sculpture-cum-display-screen. They all give their audience an aesthetic experience that briefly changes their relationship to the world, and in some cases shows them themselves in that new relationship. Interactive multimedia installation is clearly due a resurgence.

The V&A have presented Decode as a design show. I was struck by this framing of the work when I visited the show, and most of the people I have spoken to about the show since have commented on it as well. Many of the participants are graphic designers or work in design as well as art and education, but much of the work would be poorly served by being regarded as design rather than as art. It is not advertising, or presentation of anything other than itself for the most part. Where the work is information design, the information has been chosen by the designer. That said the art computing MA I attended as a student had to be called a “design” course to get funding, so possibly this is a constant. And the V&A have done a great job of presenting the work and letting it speak for itself to the visiting crowds.

This isn’t quite Cybernetic Serendipity 2.0. It excludes the conceptually and performatively, rougher edges of contemporary art computing. But these exclusions are largely practical; there is no livecoding and there are no email or self-contained web browser-based works. Some of the work is strikingly but subtly political in its representation of current social and political trends such as surveillance, online pornography and the death of privacy.

The V&A have done the conventional artworld and the general public a great service by presenting Decode. The show contains enough big and up-and-coming names in art computing and digital design to provide a convincing if necessarily incomplete survey of the contemporary scene. Decode also serves an important role for artists and students with an interest in or a stake in art computing by focussing attention on what others have achieved that can be built on.

Decode shows the achievements of the personal computing and web eras of art computing becoming established with and recognized by the broader arts establishment. The danger is that the story will finish triumphally here. Processing has become the new Shockwave, and particle systems and shape grammars are not enough in themselves for long without an accompanying progressive and deeper deeper engagement with the aesthetics and history of art, technology, wider society, or all three. Art computing is not immune to technical and aethetic conservatism. To avoid this I think that it needs to intensify, to become more like itself; to become more beautiful, to tackle larger datasets, to become more interactive. In other words, it needs to build on the achievements gathered together and presented here.

http://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/future_exhibs/Decode/

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Curated by Carolyn Kane for Rhizome September, 2009.

#60605 plus #20101 does not equal black, but it looks like it to me. And despite Newton’s insistence, a rainbow is never made from seven colours in neat lines, nor can I see millions of colours on my calibrated monitor. It is more likely that each day I engage with the screen as a greenish-blue glow infused with hits of magenta. Or as it is today: a summer grey of sea fog glimpsed through the rain. Is that a colour? Carolyn Kane curated HTML Color Codes in order to ask these questions of the relationship between colour, code, and subjectivity. Tracing a carefully structured path through twelve artworks Kane seeks to examine whether artists working with the Internet are limited to a ‘ready-made’ colour palette. Asking if digital colours reflect the programming languages that have been adopted, Kane considers whether the Internet adds its own rules for colour through the adoption of the hexadecimal system of colour values. Does the language determine the content?

The answer is, not quite. It all depends on where and how the viewer approaches the screen. Rather than trying to be paintings these works engage with the materiality of digital colour and the manipulation of a different kind of flat predetermined surface – the screen. Chris Ashley gives us rectangles within rectangles, Dlsan manipulates circles within circles, and Michael Atavar offers the blue screen of an empty window with text written as if in the condensation of a cold morning. It is the noise of the digital image embraced by the inadequacy of a gif representation of a treasure heap of digital gold in Jacob Broms Engblom’s “Gold”, or the absence of any controlling frame in Owen Plotkin’s “Firelight” and the flickering spaces nested within and alongside one another in Rafael Rozendaal’s “RGB” that suggest different rules for the digital image. In these latter works the illusion of immediacy raises a spectre of some kind of phenomenological directness.

Twentieth century colour field painting was never a single set of experiments yet it carried within it a set of cultural and formal presuppositions. The digital colour field has its own baggage set. It is inbetween: inbetween code and software, browser and window, network and bandwith. More often than not the experience of the digital colour field is the result of an image within an image or a screen within a screen. Despite its origins in hexadecimal notation digital colour is not a ready-made, but an experience and a process of light and interaction. Anyone who has attempted to capture or translate a colour between screens knows that accidents occur. Noah Venezia’s “The Rainbow Website” suggests that a kind of synaesthesia can be experienced through the screen, that colour exceeds the values assigned to it. Andrew Venell’s “Color Field Television” mimics the flicker of experimental film from the 1970s. Perception becomes a process of seeing the colours inbetween, the work turns back on itself mirrored within a screen. Structural film experiments were about exploring more than perception they too turned back to the medium. Morgan Rush Jones gets even closer with the phased colour space of “Number of ManufacturingIndustriesbyNumberof Product ClassesinanIndustry”. The work is simultaneously overloaded with image and abstracted from it. There is a strange congruence reflected here: in their formality these works do not push new experimental boundaries but reflect older ones.

Michael Demers explicitly engages the materiality of the digital medium by establishing a series of systems within which abstraction can occur. Sampling Morris Louis’s oil painting “Where” from 1960, Demers generates a sequence of flat colour planes (windows) from left to right that disappear as quickly as they appear. The drip and movement of Louis’s work is rendered temporal. Brian Piana’s “Elsworth Kelly Hacked my Twitter” also addresses the temporality of the digital. Real-time data orders the compositional frame in a direct chronological sequence. Each square is a representation of an invisible network. Manipulation of the scale, size and shape of the frame is left to the viewer. For me it is Elna Frederick’s “@ = landscape” that allows an interactive experience of the subjective dimension of colour that is specific to the digital. The click of a mouse becomes the experience of putting a finger into a stream of water and disturbing the flow. It is not necessarily the colour that makes the rain but the movement and the belief instilled in us from Super Mario that onscreen fluffy white blobs potentially contain rain. There is a cool sensuousness to the trickle of pixels as it becomes water and when left alone returns to simply being yet another onscreen blue.

There is a risk of over determination in this show, the kind of visual parity that results from too many works looking at the same thing and becoming somewhat redundant. It is the quiet spaces between the works, the mutable changing structures of the blue screen that resist this limitation. As long as bandwidth remains with us, and the links stay live, these works are infinite and through their repetition we experience an abyss of generated colour and code. These are predominately forms consisting of colour alone, and surprisingly, that is enough. This is how the medium of digital colour should be approached. There is no translucency, but there is an unlimited interplay of substitutions.

Digital Pioneers

Victoria And Albert Museum

7 December 2009 – 25 April 2010

(Illustration – Herbert W. Franke, Squares (Quadrate), screenprint, 1969/70)

Digital Pioneers is a deceptively modest exhibition hidden away in two rooms upstairs at the Victoria and Albert Museum. It contains some of the earliest examples of art produced using electronic devices and computing machinery along with some creative later work.

The bulk of the art in the show was produced between the 1950s and the 1970s. This means that it was produced or recorded as photographs from cathode ray tubes or as print-outs from teletypes and pen plotters. Some of this work will be familiar to students of the history of art computing through reproductions but as with most art reproductions do not tell the whole story.

Seeing the actual work itself is as important for art made using the paraphernalia of early digital computing as it is for art made with linseed oil and cotton duck. What Digital Pioneers drives home is just how deeply and intentionally involved early computer artists were in manipulating the aesthetically limited but socially and ideologically key technology of computing machinery. This leaves both social art historians and code aesthetes with some explaining to do, or at least some catching up.

The show starts in the 1950s with the algorithmic and electronic but non-digital and non-computational photographs of oscilloscope patterns by Ben Laposky and screen-prints of photographs by Herbert W. Franke. Most of the works included in the show are prints of one kind or another, and these are no exception. They record the movement of a beam of light on a cathode ray tube as other prints in the show record the movement of a plotter pen or a laser in a laser printer.

If Constructivism was socially realistic for revolutionary Russia then these works are socially realistic against the backdrop of NATO’s military-industrial-educational complex. They turn the technology of that culture back on itself, using it not to produce weapons or market products but to produce aesthetics. This reclaims a space for perception and contemplation that is not simply militarily or economically exploited. The obsessively quantitative managerial culture of spreadsheets and inventories yields uncomfortably to the qualitative culture of aesthetics, productively so. These strategies continue through the show. Technology is pushed beyond its intended uses to address cultural tasks.

Many of the prints in the show have a similar number of stages of production to Franke’s process of screen, then photograph, then silkscreen prints. His later plotter-drawn work is also screen printed, as are Klee-inspired generative images by Frieder Nake, and Charles Csuri’s random montage of flies. I don’t know what to make of this. It feels like something should have been lost in the move from an original to a print but plotter drawings aren’t particularly originals, being already representations of data structures in the computer’s memory.

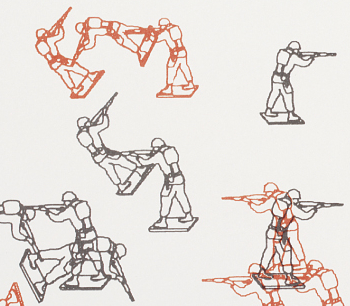

Csuri’s lithograph of randomly placed vector outlines of toy soldiers was produced in 1967 during the Vietnam War, a war that ran as long as it did in no small part due to game theory and computer simulation. There are two armies, one plotted in red and one plotted in black. They meet and presumably battle inevitably but only by chance. There’s more of the outside world in art computing than is often assumed.

William Fetter’s wonderful three dimensional vector images of human figures produced for the aircraft manufacturer Boeing, a lithograph from the Cybernetic Serendipity show of 1968, also deal with the human figure within the military-industrial complex. We should not be confused about the status of such images as art by the use and funding of computer graphics by corporations any more than we should be confused about the status of painting as art by the use and funding of oil painting by the Catholic church.

Ken Knowlton’s cheeky nudes and other typographic images of the 1960s and 1980s are an effective escape or release from the constraints of corporate information culture. I’d seen them many times in reproduction but again they are much richer visually as prints.

More detailed systems-based patterns emerge in the 1970s in the work of artists such as Manfred Mohr, Paul Brown, and Vera Molnar. This era that epitomises the approach of rule based serendipity so beloved of later Generative artists. These images are pleasurable to look at but also contain visual or psychological complexity. They also continues to push the performance of computer systems outside of their intended use cases.

By the late 1980s the technical achievements of computerised mass media were exceeding those of art computing. Pen plotters, where they were still used, were no rival to laser printers. Rendered images had to compete with the earliest rumblings of Pixar and Adobe. The increasing availability of digitally designed fashion and entertainment meant that far from being the exception, digital elements in the lived visual environment were becoming the rule.

The reactions to this that art computing in general have made are the subject of the Decode show that is also running at the V&A. Digital Pioneers instead follows the printmaking thread of art computing into the present day where artists such as Roman Verostko, Mark Wilson and Paul Brown have continued with the systems art all-overness of print-based art computing.

To continue in this way marks such work out as something different from the all-pervasive presence of digital imagery in the visual environment. The work has to look different from graphic design and new media rather than from CAD plots or teletype reports, and it does. These works remind us of the history and of the wiring under the board of digital culture. They successfully resist any attempt to reduce them to digital mass media images comparable to the output of the design software that they exist in the same era as.

This switch away from early adoption is necessary to maintain a figure/ground relationship (or a critical distance, or a constructive difference) between the general level of technology in society and the level of technology in art computing. It is not the only solution to this problem, as the Decode show demonstrates, but it is not a retreat.

As a long time fan of Harold Cohen, I found the show’s inclusion of computer generated works from his very earliest 1960s felt-tip-on-teletype-print experiments with generating figure and ground relationships computationally to a recent large-scale full-colour inkjet abstract was a real treat. Plotter drawings of abstract shapes from the 1970s and of human and plant forms from the 1980s show the progress that Cohen made in using computers to rigorously explore how art and images are created and function. Being able to study this work close-up reveals details such as debugging information in the teletype prints and the operation of the collision-detection algorithm in the 1980s images. And it provides the pleasure of seeing detailed, well-composed drawings.

This is a recurring experience in Digital Pioneers. Despite the uniformly dismissive attitude of both popular and academic criticism towards art computing the fact is that when you actually see the work in the flesh it rewards sustained attention. Not as historical or technical curiosities, but as images with cultural and aesthetic content and resonance. To ignore this and to continue to claim that this art is less than the sum of its parts would ironically be to fall prey to a particularly extreme attitude of technological determinism.

The show also contains displays of ephemera including magazines and books such as back issues of the Computer Arts Society’s “PAGE” and William Gibson’s supposedly self-erasing story on a floppy disk “Agrippa”. I’d not seen an actual copy of “Agrippa” before. PAGE back-issues are available online, but their presence here flags an important point.

The revived Computer Arts Society has been key in promoting and deepening understanding of the history of art computing in the UK. The Digital Pioneers show and its excellent accompanying book are a good example of how CAS’s project has spread out into more traditional cultural institutions, and many of the images and exhibits in the show come from the archives that CAS has donated to the V&A.

The “Digital Pioneers” book (by Honor Beddard and Douglas Dodds, V & A Publishing, 2009) serves as a catalogue for the show . It contains an informative introductory essay and printed images of many of the works on display as well as a CD-ROM with 200dpi scans of them. These scans are high-resolution enough to be able to examine the images in some detail, although they are no substitute for seeing the images in the gallery. A slightly excessive copyright licencing notice is the only indication that the book has in fact been produced as one in a series of pattern books from the V&A. It’s a must-have if you enjoy the show or have any interest in early art computing.

Digital Pioneers is an opportunity to really look at the work of early computer artists and to evaluate that work directly rather than through the medium of poor reproductions or through the fog of received critical opinion. As a slice of artistic history that just so happens to have been produced on computer it contains much to reward both the eye and the mind.

Update: Two recently published books provide more extensive background to the period covered by the show, making the history of this fascinating era available to current practitioners –

White Heat, Cold Logic: British Computer Art 1960-1980‘ edited by Charlie Gere et al covers the history of British computer art and the Computer Arts Society.

A Computer in the Art Room by Catherine Mason describes the relationship between British art schools and computing (which is how I became interested in this area in the first place).

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

A collaborative review by Marcello Lussana and Gaia Novati

The article features artwork, projects and conference highlights from individuals and groups/organisations such as Honor Harger, Gebhard Sengmuller, Franz Buchinger, Ryoji Ikeda, Julian Oliver, Damian Stewart, Clara Boj, Diego Diaz, Ken Rinaldo, Michell Teran, Aaron Koblin, Daniel Massey, F.A.T, Warren Neidich, Kahaimzon Michel, Bruce Sterling, I-Wei Li, Steve Lambert Matteo Pasquinelli and more…

This year’s Transmediale.10 Festival explores the theme ‘future’ through connections between arts and technology. A part of the introduction read “Futurity is a concept that examines what the ‘future’ as a conditional and creative enterprise can be. At its heart lays the intricate need to counter political and economic turmoil with visionary futures. […] what roles internet evolution, global network practice, open source methodologies, sustainable design and mobile technology play in forming new cultural, ideological and political templates.”

2010 is a year that has often represented the future in Science Fiction literature, such as Arthur C. Clarke’s 2010: Odyssey Two, and now here we are. A good time to compare how we percieved the future, the past, and assess what is really happening, what we lost and what we have gained, and ‘perhaps’ find better ways to proceed. Art can offer different perspectives, ways of seeing and understanding, revealing our present states of being, sharing alternatives or even new meanings for our futures. This festival allows those visiting and taking part, an opportunity to explore, negotiate possible avenues in understanding together, what all this means.