JENIFA TAUGHT ME

CONSTANT Dullaart’s solo show Stringendo. Vanishing Mediators, Caroll/Fletcher.

Occupying both floors of the ultimate O’Doherty white cube of Carroll/Fletcher, Dullaart’s first solo UK survey show Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators consists of 27 works – many of them newly commissioned. The works have in common Dullaart’s pervasive aspirational tactic of queering and laying bare the architecture – both physical and virtual – of our networked yet doggedly analogue broadcast lives. Retaining a sense of sepia-tinted nostalgia for the Pong era Internet, many of the works in the show pay tongue-in-cheek homage to the revolutionary and democratic aspirations placed on the web at the beginning of its popular adoption – albeit primarily by white, male middle class Americans. Throughout the exhibition, Dullaart forensically tracks, seeds and traces remnants of our digital past and places them in direct dialogue with the power relations embedded in the terms and conditions of how these technologies have remediated the way we encounter and interpret our world now. This unveiling and excavating of the digital gesture – whether personal or brand mediated – and the freezing of the smoke and mirrors affect of software semantics isolated on the plinth of the gallery. It will be familiar ground for many of us in the business of the aestheticization of our precarious position as prosumers in surveillance society. However, as Dullaart lays bare the soft terrorism of the interface and the slowly encroaching disillusion of the clunky binary “digital” and the “physical”, he points towards a new way of visualising the architecture of our messy public/private, social/political pathological states of disarray by introducing The Balcony as a newly envisaged site of resistance and broadcast.

Stepping off the street and into Constant Dullaart’s recent solo show Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators at Carroll/ Fletcher on a sweltering summer afternoon I am immediately transported into a trippy AC’d noughties Snappy Snaps.

Dullaart’s signature, and now Guardian-famous, eponymous series Jennifer in Paradise acts as the hero image for the immersive world of blissfully glossy software-mediated wallpaper and slickly produced lenticular prints hanging in the entrance gallery. A Miami-hued display of software’s extensive lexicon of brushstrokes, filters and masks is flamboyantly demonstrated on the lonely yet aspirational image of a beautiful woman sitting on the beach looking out onto the tropical horizon. The promiscuous past of this image is well rehearsed; from its origins as a 1987 holiday snap – taken by co-creator of Photoshop John Knoll – to its use as crash test dummy for his ground-breaking popular software and its voracious adoption by the newly indoctrinated Photoshop masses as a subject of visual vivisection frames the staging of this exhibition. Dullaart’s archeological impulse to sniff out the rare software artefact of Jennifer points towards a general fetishization of the magic tipping point of the analogue/digital past –conjuring up a time when photography’s authenticity was still a battle to be fought. In a conversation with the artist at the appropriately ambiguous location of The Photographers Gallery shortly before his show opened, Dullaart emphasises the enduring pull of the image in his own practice. Describing the logic of the exhibition’s strategy, he sees the pasting of the Jennifer wallpaper as a “doubling” [1], or colonisation of his ongoing Jennifer experiment.

Dullaart’s Jennifer journey through the lexicon of data manipulation started when he embedded a secret stenographic message in the first re-appropriated images of Jennifer as a kind of “prize” for his growing online viral public. The first iteration(s) of Jennifer in Paradise explored the Internet’s opacity, highlighting the extent to which onscreen data is manipulated and controlled, enhanced or deformed. By celebrating and transporting the cyber-famous Jennifer into the gallery context in the form of selective editions, copies, or “abbreviations” of the digital, networked manipulation of the image, these artefacts act as both signifiers of the artists’ practice and as tempting photographic editions in their own right. A fact the artist is well aware of. However, the overarching social commentary implied in the freezing of this signifier of mass viral circulation is that the image became a coded Trojan horse for the prosumers’ 2.0 hypermarket as it was seeded, tracked mediated, remediated and mimetically distributed through the newly democratised digital commons.

It is in this mimetic gesture of versioning – a trope embedded in the very DNA of software development – that the artist does not just reference and make visible software’s surface gestures, but actually performs software’s versioning impulse, exposing it as a form of corporate cultural imperialism and spotlighting the newly negotiated role of authorship in the process. The artist’s persistent and persuasive disruption of the role of authorship is a common and recurring obsession running through his practice – from objects, to online queering of domain names, to his performances. A personal/impersonal example of this is played out in the exhibition by a row of seemingly innocuous family photographs. The series of family pictures from the 1980s are, according to Dullaart, the cleanest example of performative authorship. The photos were simply sent to Apple co-founder Steve Wozinak for him to sign and send back to the artist – resulting in the “re-authoring” of Dullaart’s childhood memories. This simple performance of capital control and authorship of so-called private identity is mainlined into Dullaart’s practice, and speaks to the artist’s core impulse: “this is exactly what I do – I take what isn’t public and I re-posses and reprocess these artefacts and re author them into a different spectrum”. [2]

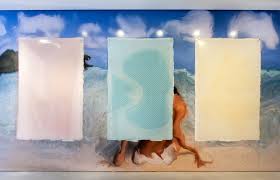

In another act of ambiguous reverie of the commercial canon of software are the three pieces entitled Bill Atkinson demonstation drawing, (no.5, 12 and 18) hanging on the other side of the gallery, positioned against the Jennifer-tiled wallpaper. These drawings from the 23 stages of the first drawing made by Macpaint creator Bill Atkinson are printed in monochromatic hues sandwiched between photopolymer plates. These meticulously restored physical gestures of one of the first drawings executed by commercial software are particularly important for the artist. He sees this attempt at drawing made in the “strong consumer software” of Macpaint as a kind of totem or signifier of the emerging lexicon of the new canon in art history.

Beautiful fetishistic rubbery objects in themselves, the physicality of these works demonstrates the materially-dependent, performative intent in Dullaart’s practice. As these monochromatic objects react and change to UV light – hardening and cracking – any collector of his work needs to embrace the precarious temporality of the objects themselves. This is true of all of his work – including domain names, websites, his own online identity etc. and Dullaart emphasises that the conscious situating and staging of his works in the framework of time is one of the most vital components of his practice.

This animated relationship to instability and time- dependency is clearly demonstared in his player paino piece Feedback with Midi Piano Player at the heart of the exhibition. An algorithm interpreting polymorphic songs is played out through the grand piano in the gallery in an apparent circus-like celebration of the computer’s magical powers. However,as the recital unfolds, it is full of little mistakes – the songs are too complex for the computer to relay in a coherent feedback loop. For Dullaart, the inaccuracy and amateur quality of the computer/piano recital delivers a quasi -human quality of cuteness – an increasingly desirable quality in our popular technology, and an indication of the drive towards the synthetic anthropomorphism of digital objects and structures in general. This inevitably recalls Marx’s highly questionable use of anthropomorphizing comparisons of the commodity to children and women to underscore the “fetish character” [3] of commodities – the phantasmatic displacement of the sociality of human labour onto its products, as they appear to confront each other as if operating independent social lives of their own. In this sense, the “cuteness” in Dullaart’s piece might be seen as an intensification of commodity fetishism’s logic redoubled (like Jennifer) – as the viewer is connected to the unavoidable fantasy of fetishism, itself already an effort to find an imaginary solution to the irresolvable “contradiction between phenomenon and fungibility” [4] in the commodity form.

However, if this “cuteness” maintains fetishism’s overarching illusion of the object’s animate qualities – in this case the clumsy performance- at the same time it wants to deny what, in Marxian terms, these animated commodities articulate as “Our use-value may interest men, but is no part of us as objects…We relate to each other merely as exchange values.” [5]

Dullaart then shifts his attention to the main focus of the exhibition – the conscious construction and showcasing of his proposition of a new way of entering into a contract with our networked, hyper-published -selves: the balcony. The two physical balconies presented in Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators (one of which is accompanied by a digital ticker-tape text of his Balconism manifesto) are both visual prompts and, in a sense, demos, of Dullaart’s concept of balconisation. In direct acknowledgment of the hyper- mediated image of Julian Assange standing on the balcony of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London – Dullaart starkly illustrates this liminal, politically charged space where we bear witness to a clear slippage between UK and Ecuadorian territory. To Dullaart, the balcony represents a ‘space outside society’ [6], and this new space of public address marks a shift in responsibility in self-broadcast/publication in the digital commons and the social media sphere. According to Dullaart, we all need to recognise our position on the balcony in our hybrid public/private pathology and modus operandi of quasi-addictive self-broadcast.

On the balcony we should be ready to escape the warm enclosure of the social web, to address people outside our algorithm bubble. In the context of the show, the balcony is positioned as a higher order theory for how we should respond to the process of digitalisation as a whole, to how corporations and programmes structure our understanding of the world. We need to stand on our particular balcony ‘and choose to be out in public and we have to define cultural codes of how to do that’. [7]

What Dullaart’s exhibition Stringendo, Vanishing Mediators offers anew is an alternative proposition of spatial code through which to understand our steadily (re) negotiated locations of private and public space and the possibility of somewhere inbetween from which to enact a certain kind of everyday De Certeauian [8] tactic – the Balcony.

Dullaart’s solo exhibition ended at Carroll / Fletcher on 19th July 2014.