In thinking about the relationship between science fiction and social justice, a useful starting-point is the novel that many regard as the Ur-source for the genre: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). When Shelley’s anti-hero finally encounters his creation, the Creature admonishes Frankenstein for his abdication of responsibility:

I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king, if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. … I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, who thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. … I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.

Popularly misunderstood as a cautionary warning against playing God (a notion that Shelley only introduced in the preface to the 1831 edition), Frankenstein’s meaning is really captured in this passage. Shelley, influenced by the radical ideas of her parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, makes it clear that the Creature was born good and that his evil was the product only of his mistreatment. Echoing the social contract of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Creature insists that he will do good again if Frankenstein, for his part, does the same. Social justice for the unfortunate, the misshapen and the abused is what underlies the radicalism of Shelley’s novel. Frankenstein’s experiments give birth not only to a new species but also to a new concept of social responsibility, in which those with power are behoved to acknowledge, respect and support those without; a relationship that Frankenstein literally runs away from.

The theme of social justice, then, is there at the birth also of the sf genre. It looks backwards to the utopian tradition from Plato and Thomas More to the progressive movements that characterised Shelley’s Romantic age. And it looks forwards to how science fiction – as we would recognise it today – has imagined future and non-terrestial societies with all manner of different social, political and sexual arrangements.

Shelley’s motif of creator and created is one way of examining how modern sf has dramatized competing notions of social justice. Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (1950) and, even more so, The Caves of Steel (1954) ask not only the question, ‘can a robot pass for human?’, but also more importantly, ‘what happens to humanity when robots supersede them?’. Within current anxieties surrounding AI, Asimov’s stories are experiencing a revival of interest. One possible solution to the latter question is the policing of the boundaries between human and machine. This grey area is explored through use of the Voigt-Kampff Test, which measures the subject’s empathetic understanding, in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) and memorably dramatized in Ridley Scott’s film version, Blade Runner (1982). In William Gibson’s novel, Neuromancer (1984), and the Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell (1995), branches of both the military and the police are marshalled to prevent AIs gaining the equivalent of human consciousness.

Running parallel with Asimov’s robot stories, Cordwainer Smith published the tales that comprised ‘the Instrumentality of Mankind’, collected posthumously as The Rediscovery of Man (1993). A key element involves the Underpeople, genetically modified animals who serve the needs of their seemingly godlike masters, and whose journey towards emancipation is conveyed through the stories. It is surely no coincidence that both Asimov and Smith were writing against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement, but it is also indicative of the magazine culture of the period that both had to write allegorically. In N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy (2015-7), an unprecedented winner of three successive Hugo Awards, the racial subtext to the struggle between ‘normals’ and post-humans is made explicit.

Jemisin, like Ann Leckie’s multiple award-winning Ancillary Justice (2013), is indebted to the black and female authors who came before her. In particular, the influence of Octavia Butler, as indicated by the anthology of new writing, Octavia’s Brood (2015), has grown immeasurably since her premature death in 2006. Butler’s abiding preoccupation was with the compromises that the powerless would have to make with the powerful simply in order to survive. Her final sf novels, Parable of the Talents (1993) and Parable of the Sower (1998), tentatively posit a more utopian vision. This hard-won prospect owes something to both Joanna Russ’s no-nonsense ideal of Whileaway in The Female Man (1975) as well as the ‘ambiguous utopia’ of Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974). Leckie, in particular, has acknowledged her debt to Le Guin, but whilst most attention has been paid to the representation of non-binary sexualities in both the Ancillary novels and Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), what binds both authors is their anarchic sense of individualism and communitarianism.

Whilst sf has, like many of its recent award-winning recipients, diversified over the decades, there is little sense of it having abandoned the Creature’s plaintive plea in Frankenstein: ‘I am malicious because I am miserable.’ It is the imaginative reiteration of this plea that makes sf into a viable form for speculating upon the future bases of citizenship and social justice.

Keep calm and carry on monitoring the media: a review of Monitorial Citizen

NeMe (Cyprus), 9th December 2017, part of the State Machines programme

One couldn’t have wished for a more grounding response to contemporary media anxieties than this event. I don’t mean that the conference was all rainbows and lolkittens. I mean that it collected and tackled serious issues about the contemporary media landscape, its decentralization and its paranoias. It brought together perspectives on monitorial citizenship, citizen participation and citizen journalism –increasingly discussed in journalism and citizenship studies as new, post-modern, or alternative forms of civic engagement that also involve new, post-modern or alternative practices of media participation– and how this phenomenon can reinforce democratic ideals, and counteract forces or fears for their dissolution.

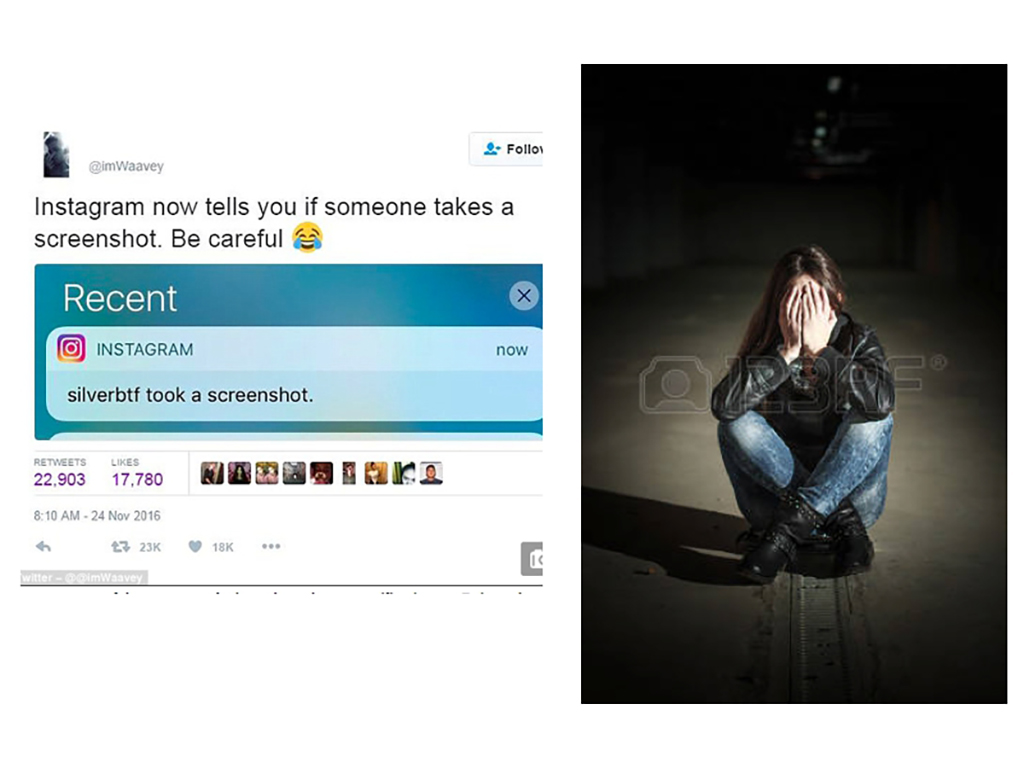

By all means, there seems to be a lot for us to worry about, a condition which the conference takes as its starting place. As moderator Corina Demetriou mentioned during her introduction, there’s the increasing fragmentation and polarization of our world where the success of populist rhetoric and the degradation of political discourse raises concern about our democratic institutions. Then there’s the proliferation of fake news, the dominance of media-scepticism, of conspiracy theory and of justifiably alarmist parental control discourse. And further yet, there’s the democratic failures of contemporary mass media, the corporate nature of social media, and concerns about the failures of media-education. All these in the face of increased surveillance and online censorship instituted with the excuse of / in order to battle all sorts of nightmarish villains.

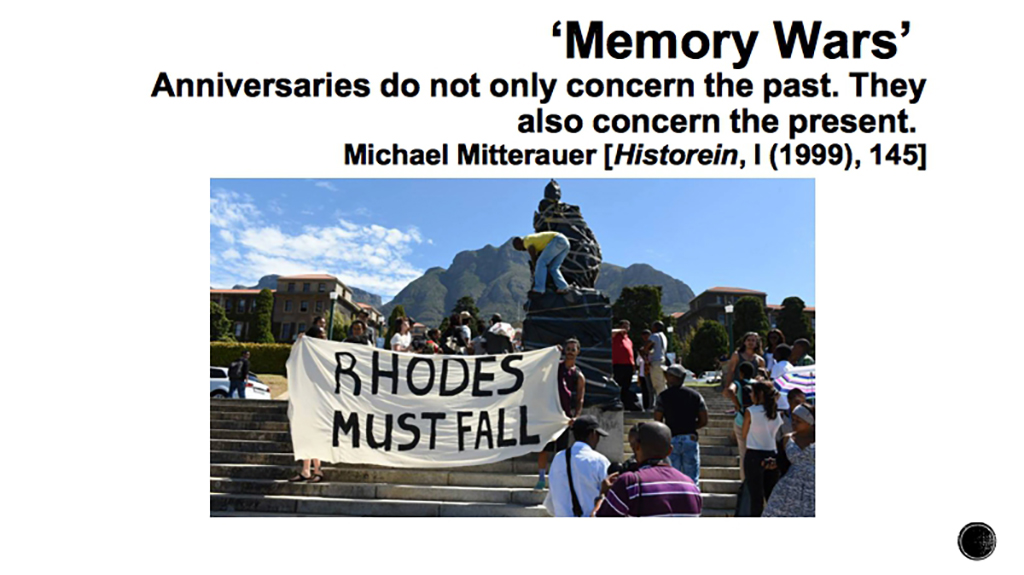

The conference had the intended side-effect of facing and disarming most of the above, not least by providing historical context and balancing fears with contemporary research, following up criticisms with constructive questions, and offering numerous examples of citizen monitoring at work to an inspiring effect. NeMe gathered its speakers around the urgent premise of the potential for political change that is contained in networked citizen journalism (after Michael Schudson 1998) or citizen witnessing (after Stuart Allan, 2013). This was done in relation to what NeMe frames as a growing demand for political and corporate clarity that brings citizens immediate access and grants crucial issues a kind of evanescence: a transparency that is double-edged, both in terms of exposure, but also a tendency to fade or be drowned out in a sea of information.

It helps to think of the conference in four parts. First, it provided an introduction to the discursive context and the development of the notion of citizen witnessing (Stuart Allan). Second, it moved on to crucial debates in media education (Joke Hermes) and children’s rights of access to information (Cynthia Carter). Third, it introduced a discussion of the politics of democratic citizen participation in theory and online (Nico Carpentier) and the transformative potential of grassroots media monitoring practices towards conflict transformation (Nicos Trimikliniotis). And it concluded, with satisfying momentum, with a discussion of monitorial practice from an artist perspective (James Bridle).

In the first presentation, the conference defined the field and what is at stake in terms of the media establishment’s clash with the simultaneous need to subsume new developments in citizen journalism: Stuart Allan set-up the context for this through a discussion of the idea that “somebody should be telling this because journalists aren’t.” His overview reached from the Kennedy assassination, to the definition of the Arab Spring as the Twitter revolution, to #blacklivesmatter, and the WITNESS human rights initiative. Allan also reflected on negative reactions from the world of professional journalism where citizen reporting is cast as “ghoulish voyeurism enabled by contemporary technology.” He most interestingly, juxtaposed professional “helicopter” or “parashoot” reporting, done according to editorial directives, with an emergent form of reporting from within. A form that is embedded and unsanitised, and comes in the form of unapologetically subjective documentation, where the amateur camera approaches truth or reality with an immediacy that trumps formal news, and demonstrates how purposeful citizen witnessing can bring about positive social change.

Then came two complementary discussions of sensitive issues around the failures and alarms of contemporary media-education (Joke Hermes) and children’s access to information, with emphasis to their online participation and their potential for political contribution (Cynthia Carter). Both speakers have been working towards the deconstruction of the stereotypic fear that it is a dangerous online world for young people, and they’ve been doing this in different ways and from different angles. Hermes discussed how a quarter century of media education has succeeded in breeding fear and mistrust rather than ways to corroborate and cross-reference. She made the very convincing argument that we need a plan for long-term engagement rather than immediate survival. That we must work towards the strategic teaching of the difference between downright holistic mistrust and meaningful engagement. That we may construct a perspective for cultural citizenship that makes “learning how to listen” (to disengaged sceptics) a priority: part of a new set of conditions for citizenship, where “irony, satire, and playing games” are understood as survival mechanisms, and “ways of blocking screening and fooling one’s parents are understood as useful tools for children to survive in all this, without giving in to conspiracy theories.” Following up from Hermes, Cynthia Carter explored arguments around parental control and its misunderstandings, with a discussion of how research on news media remains incomplete by failing to include the voices of children. She argued against perspectives that cast children as “passive recipients of information that is going to socialise them.” She emphasised how children’s civic rights are undermined by the mistaken perception that, primarily, rather than engaged, they need to be protected. She offered examples where interventions by children exercising monitorial citizenship, have the potential to change perceptions about children’s political interests and their capacity for meaningful, world-changing participation.

Nico Carpentier connected issues of online participation with broader debates and definitions centering on participation as integrated with democratic ideas. He discussed the development of participation-related discourse online and offline, and the posturing contained in such theoretical or practical endeavours vs. their democracy-reinforcing capacity. He highlighted a serious problem with the idealisation of the democratic capacity of online participation: that, for example, “we still haven’t looked at the radical right form of online participation where neo-nazis are participatorily deciding whether they should kill somebody.” Carpentier argued for the need to further “democratise democracy” across fields like the arts and the media, and “do more than pay lip service to the logics of participation.”

Next, Nicos Trimikliniotis introduced debates around participation and citizen journalism in relation to Cyprus, and to argue for the need to compare struggles and national contexts, particularly in relation to peace journalism and the potential for overcoming austerity and chauvinist citizenship models. He emphasised the role of the media in conflict transformation, in defining the nature of conflict and division: its contextualisation and relativisation, and transference towards social and other issues. For him, the creation of third spaces that defy the long-embedded interests of mainstream media is a crucially valuable new element. He identified such a critically valuable third space in the practice of the monitorial citizen. He used the example of the Cyprus-based collaborative online journalism collective Δέφτερη Ανάγνωση (trans. Second Reading), to argue that it indeed possible to undercut colluding media, and transform the reporting, the investigation, and the very nature of professional journalism, with the help and participation of monitorial citizens, intellectuals and artists.

Finally, James Bridle introduced a multilayered example of his own monitorial artistic research practice, an exercise of monitorial citizenship that actually researched issues of citizenship, migration, and asylum. He focused on a particular project where he worked to cross-reference details left out of a story in the UK press about Theresa May putting asylum seeker and hunger striker Isa Muazu on a private jet for deportation (2013). Bridle tried different methods in order to find out where this jet landed and to investigate the systemic, legal and spatial conditions for this kind of deportation. He spoke about the value of collectively maintained online tools that pool information through crowdsourcing, such as tools designed by the flight-spotting community, in this case making public the capacity to track flights. Bridle’s investigation led to a detention centre next to Heathrow, and then to the architectural mapping of this facility, where secret deportation trials seem to be taking place. He proposed this as a way of using the ability to research and cross-reference information through new tech, to make visible something that wasn’t visible before, and thus draw a picture of the system that produces a particular kind of story. In this case a story of deportation, also connected to the debate about global surveillance, by performing a kind of reverse surveillance.

Most interesting, and as a conclusion to the conference, Bridle made transparent his own questions about this instinct of monitorial citizenship: the issue that bringing things to view could be a solution to injustice. He pointed out that his own investigative whistleblowing and NSA surveillance, have in fact, the same logic behind them. Both top down centralised government surveillance, and bottom up citizen-driven monitoring or reverse surveillance are based on the logic that there’s something secret and if we bring it to view, then something will be radically transformed. Except according to Bridle this is not fully accurate. There is a danger here that we may make the invisible visible but remain blind to the systemic forces that brought it to be in the first place.

The discussion following the presentations focused on the potential of citizen monitoring given local Cypriot peculiarities, returning to the example of Δέφτερη Ανάγνωση, with members of the audience introducing the consideration that the structure of coordinated efforts of citizen monitoring (whether flat, or hierarchical, or anonymous, and so on) can play a role in its potential to set-up democratic resistance. The formal discussion transformed into after-conference mingling over drinks and finger food that was good enough to keep people processing in small groups for over an hour. My own conversations pushed onwards from James Bridle’s point about our unwitting complicity with surveillance logics: do we try to resist such logics? (The answer may be that we can try to temper them). This included a conversation with Joke Hermes, making the connection with a recent article by James Bridle documenting weird and often disturbing algorithmically generated youtube videos targeting children (Bridle, 2017), and putting the question of where to draw the line between parental concern and parental panic. (The answer seems to be gently, by avoiding random overexposure at the preverbal stage, not attempting totalitarian control, and focusing on being there and paying attention).

There’s a lot to pick up on in conclusion, aside from my insolent and possibly unjust isolation of one-liners in bold, for which I must ask the speakers’ forgiveness. I am most interested in two elements that seem especially innovative contributions to what is already a very rich and intensely investigated intersection of scholarly work on journalism and citizenship. This conference went the extra step to further bridge this growing field with other sides of media theory: First, in connection with peace scholarship and local issues around media collusion and their effect on conflict transformation through the work of Nicos Trimikliniotis. And secondly the connection made with educational theory and cultural studies through the work of Joke Hermes and Cynthia Carter, a beautifully resonating combination with a feminist focus on understanding, rather than fear or control.R

Photographs and videos by Sakari Laurila

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.