We are delighted to share with you our Spring season of art and blockchain essays, interviews and events, offering a wide spread of exploration and critique.

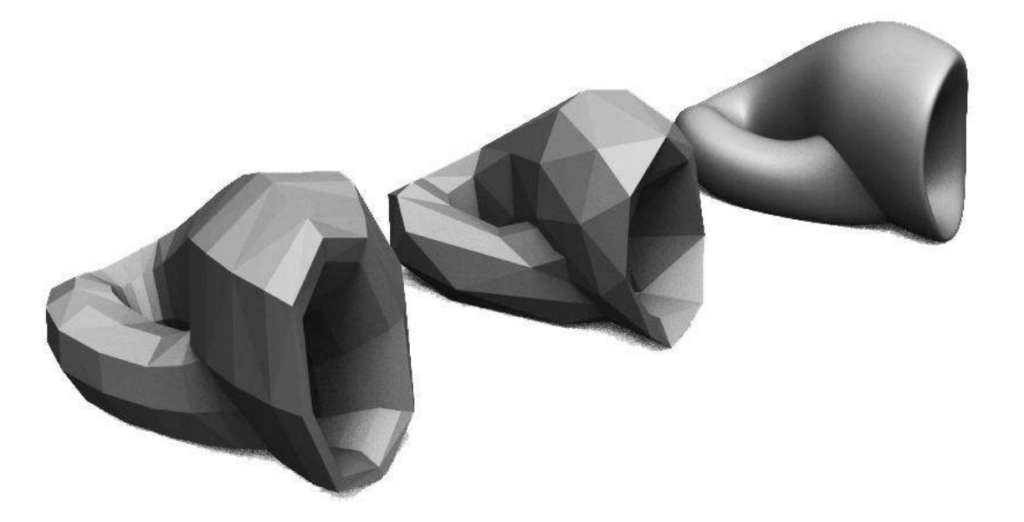

The blockchain is an evocative concept, but progress in ideas of cryptographic decentralisation didn’t stop in 2008. It’s helpful for artists to get a sense of the plasticity of new technical media. So first we are pleased to share with you Blockchain Geometries a guide by Rhea Myers to the proliferation of blockchain forms, ideas and their practical and imaginative implications.

In Moods of Identification Emily Rosamond writes her response to our second DAOWO workshop, Identity Trouble (on the blockchain). She reflects on both ongoing attempts to reliably verify identity, and continuing counter-efforts to evade such verifications.

Mat Dryhurst and Holly Herndon speak here with Marc Garrett in an interview republished from our book with Torque Editions Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain (2017). Mat and Holly convey a sense of excitement about developments and opportunities for new forms of decentralised collaboration in music.

Finally you can book your place on future events at the DAOWO blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts.1 Download the DAOWO Resource #1 for key learnings, summaries of presentations, quotes, photographs, visualisations, stories and links to videos, audio recordings and much more from our first two events about developments in the arts and the trouble with Identity.

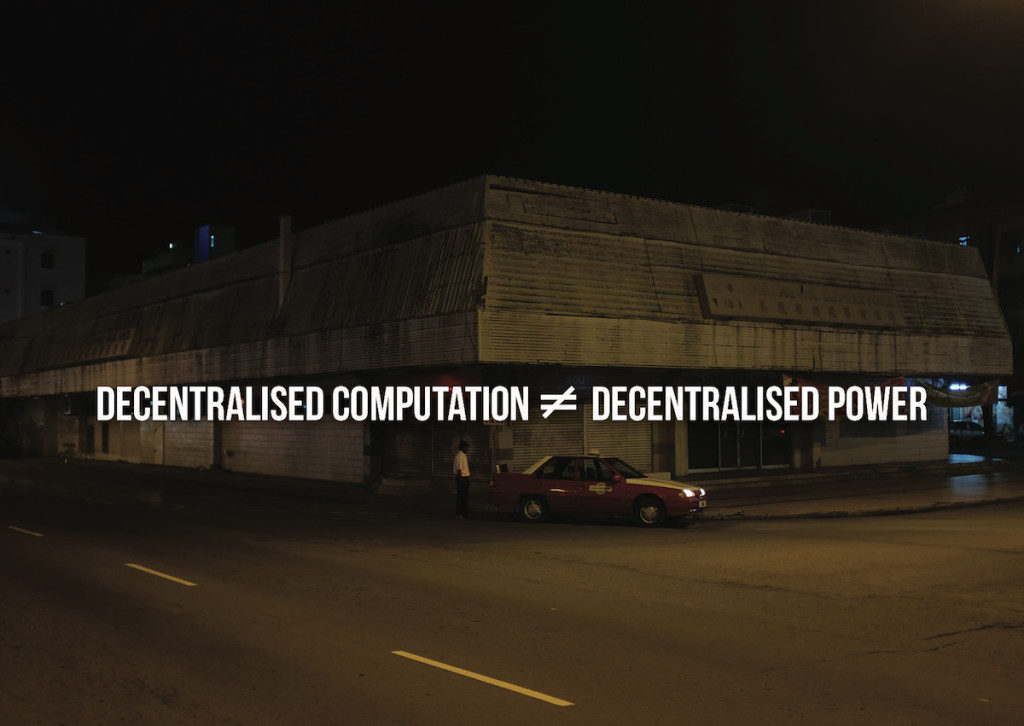

The blockchain is 10 years old and is surrounded with a hype hardly seen since the arrival of the Web. We’d like to see more variety in the imaginaries that underpin blockchains and the backgrounds of the people involved because technologies develop to reflect the values, outlooks and interests of those that build them.

Artists have worked with digital communication infrastructures for as long as they have been in existence, consciously crafting particular social relations with their platforms or artwares. They are also now widely at work in the creation of blockchain-native critical artworks like Clickmine by Sarah Friend2 and Breath (BRH) by Max Dovey, Julian Oliver’s cryptocurrency climate-change artwork, Harvest (see featured image) and 2CE6… by Lars Holdhus3, to name but a few.

By making connections that need not be either utilitarian nor profitable, artists explore potential for diverse human interest and experience. Also, unlike on blockchains, where time moves inexorably forward (and only forward) – fixing the record of every transaction made by its users, into its time slot, in a steady pulse, one block at a time – human imaginative curiosity can scoot, meander and cycle through time, inventing and testing, intuiting and conjuring, possible scenarios and complex future worlds. They allow us to inhabit, in our imaginations, new paradigms without unleashing actual untested havoc upon our bodies and societies.

Back in 2008 the global banking system was bailed out by governments with tax payers’ money. Meanwhile a 15 year explosion of web-inspired, decentralised, mutualist-anarchist DIWO (Do It With Others)-style cultural actions and practices ebbed (though its roots remain and go deep). The global network of human attention and resources were, by this time, well and truly re-centralised. The “big five” now owned, and often determined, our communication and expression. Post-Internet artists rejected platform-building as a social artform and instead, took as their materials, lives mediated through social media and corporate owned platforms. Some dived into the marketing vortex, to revel and participate in the heightened commodification of art.

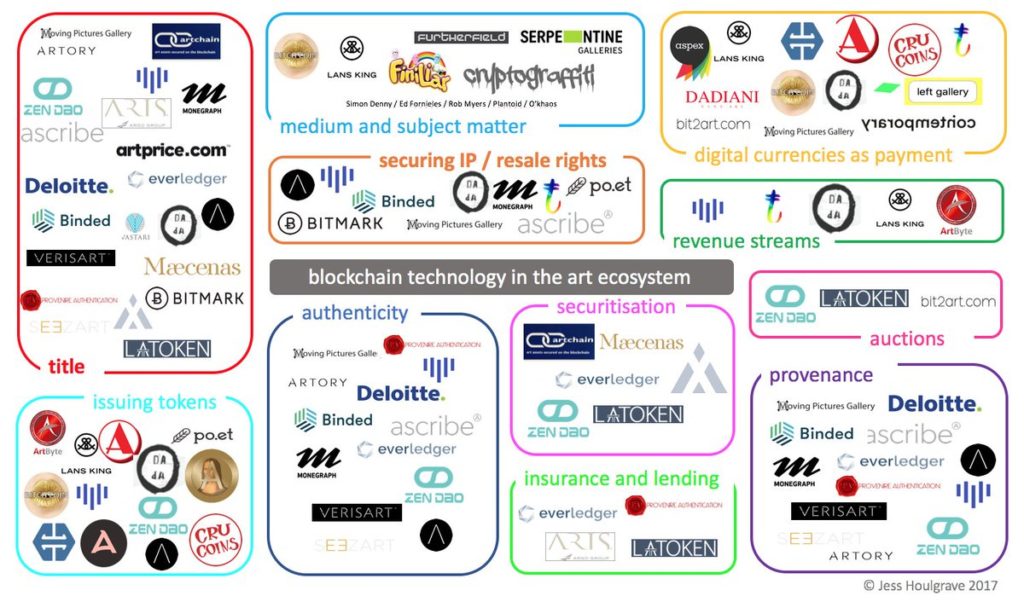

With the introduction of the blockchain protocol on the Internet we see a reversed direction of travel in the artworld, with major developments coming more quickly from the businesses of art, which reassert art’s primary status as an asset class, than from those artists experimenting with new forms of experience and expression enabled by its affordances. Now intermediaries of art world business are moving into blockchains (also sometimes called the “Internet of money”) with a focus on provenance, authentication, digital arts made scarce again with IP tracking, fractional ownership, securitisation and auction4. It is blockchains for art, any art, as long as that art can be owned and commodified. This may be seen as a good thing, generating and distributing increased revenues to ‘starving artists’. Also perhaps inevitable, as that which cannot be owned is hard to represent on a blockchain ledger.

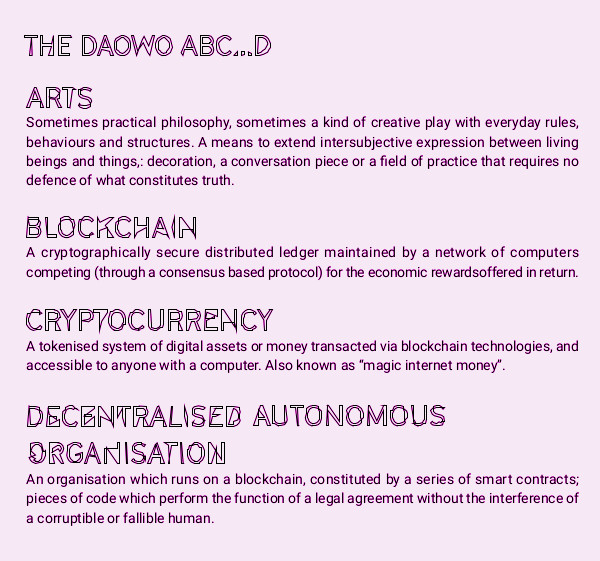

In his new book Reinventing democracy for the digital condition, (2018) Felix Stalder notes that people are increasingly actively (voluntarily and/or compulsorily) participating in the negotiation of social meaning through the “referentiality, communality, and algorithmicity, […] characteristic cultural forms of the digital condition”. In 2015 the Ethereum blockchain launched with a new layer that could run “smart contracts”, pieces of code which act as autonomous agents, performing the function of a legal agreement without the interference of a corruptible or fallible human5. These can be combined to perform as blockchain-based companies called Distributed Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) and there are a plethora of blockchain implementations and political agendas now developing. How these unfurl will affect our ability to relate to each other, to deliberate, decide and cooperate with each other as individuals, organisations and societies.

So for us the promise lies in platform-building: by-and-for communities of experimental artists (in the expanded sense of the word), participants and audiences who want to create not just saleable or tradeable art objects6 but artworks that critique the relationship between art and money, and expand the contexts in which art is made and valued.

‘AltCoins, cryptotokens, smart contracts and DAOs [Digital Autonomous Organisations] are tools that artists can use to explore new ways of social organisation and artistic production. The ideology and technology of the blockchain and the materials of art history (especially the history of conceptual art) can provide useful resources for mutual experiment and critique’ – Rhea Myers7

While FairCoin (being rolled out by FairCoop with the Catalan Integral Cooperative) puts new forms of decentralised social organisation into practice on the ground, blockchain based art projects such as Terra0 and Plantoid by O’khaos offer examples of governance systems and invite us to critically “imagine a world in which responsibility for many aspects of life (reproduction, decision-making, organisation, nurture, stewardship) are mechanised and automated.”8 Both artworks demonstrate functioning systems and help us to think through how we might determine and distribute artistic (and other) resources, their value, and the rules for their co-governance for the kinds of freedoms, commonalities and affiliations that are important for the arts.

It may take a while. What to value and how to value it is a particularly tangled question. The technical infrastructure of the blockchain is at the stage of development that the Web was at in the early 90s (blockchain technologies are less forgiving, require deeper programming knowledge and are therefore more expensive to build than web pages or platforms) which, along with the get-rich-quick vibe of non-community-platform projects, might be why there are still so few community platforms actually in operation. Resonate.is the cooperatively owned music streaming service is an inspiration in this regard. It is a platform for musicians – creators and listeners – that opens up the governance of its resources to everyone who has ever created or listened to its music. It demonstrates one way in which a DIWO ethos might work.

Helen Kaplinsky is exploring how to bootstrap to the blockchain, Maurice Carlin’s Temporary Custodians project which realises an alternative system of peer2peer art ownership and stewardship at Islington Mill9.

Three preoccupations dominate 2018 New Year blogs and commentary that mark the blockchain’s 10th anniversary: blockchains as cash cults; doubts about the actual utility of blockchains and; the environmental impact of Bitcoin (still, erroneously interchangeable with the blockchain in the minds of lots of people). We add to these our concern about the intensification of control enabled by these infrastructures, AND the simultaneous conviction (shaped by deep collaborations and hard criticisms over the last years) that blockchains have the potential to enable and stimulate new forms of social organisation, resource distribution and collaboration in the arts.

The first two preoccupations match exactly the commentary surrounding the early days of the Web and we know how that turned out. The remaining concerns are grist to the mill of our ongoing programme of publications, films, exhibitions and events. The technologies are only now stabilising to allow more grass-roots infrastructural developments.

We invite you to bring your own lens of constructive critique, gather a crowd to debate and explore how we might pull blockchains into art, on the arts’ own terms, and to gain an understanding of why it is worthwhile.

If you’re interested in Furtherfields critical art and blockchain programmes with various individuals, groups and partners since 2015. You could check out how it all started, watch our short film, read this book, visit this exhibition, or archives and documents of previous exhibitions10, 11, read reviews and debate, and join us at our ongoing DAOWO blockchain lab series, devised with Ben Vickers (Serpentine Galleries) in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme12

I arrived at the Transmediale festival late Friday afternoon, which was hosted as usual at Das Haus der Kulturen der Welt (The House of World Cultures) in Berlin. The area where the building is sited was destroyed during World War II, and then at the height of the Cold War, it was given as a present from the US government to the City of Berlin. As a venue for international encounters, the Congress Hall was designed as a symbol of ‘freedom’, and because of its special architectural shape the Berliners were quick to call the building “pregnant oyster” [1] The exterior was also the set for the science fiction action film Æon Flux in 2005. Both past references link well with this festival’s use of the building. I remember during my last visit, in 2010, standing outside the back of the building watching an Icebreaker cracking apart the thick ice in the river. The sound of the heavy ice in collision with the sturdy boat was loud and crisp. This sound has stayed with me so that whenever I hear a sound that is similar I’m immediately transported back to that point in time. Unfortunately, this time round there was no snow, instead the weather was wet, warm and slighty stormy.

Last year’s festival explored the marketing of big data in the age of social control. This year, the chosen format was entitled conversationpiece, with the aim of enabling a series of dialogues and participatory setups to talk about the most burning topics in post-digital culture today. To give it grounding and historical context the theme was pinned to the “backdrop of different processes of social transformation, 17th and 18th century European painters perfected the group portrait painting known as the “Conversation Piece” in which the everyday life of the aristocracy was depicted in ideal scenes of common activity.” In recent years the festival has scafolded its panels, workshops and keynotes to grand, central themes to guide its peers and visitors, along with a large-scale curated exhibition. If we view the four interconnected thematic streams- Anxious to Act, Anxious to Make, Anxious to Share and Anxious to Secure – we might guess that the festival curators are also anxious to save all the resources (and celebrations) for next year, which is after all, Transmediale’s 30th birthday.

So, I was curious to see how my brief time here would unfold…

This review is focused on the hybrid event Off-the-Cloud-Zone. It featured presentations, talks and workshops, starting at 11 am, going on until 8pm. Hardcore indeed. It demanded total dedication, which unfortunately I was not able to give. However, I did offer my attention to the rest of the proceedings from lunch time until the end. It was moderated by Panayotis Antoniadis, Daphne Dragona, James Stevens and included a variety of speakers such as: Roel Roscam Abbing, Ileana Apostol, Dennis de Bel, Federico Bonelli, James Bridle, Adam Burns, Lori Emerson, Sarah T Gold, Sarah Grant, Denis Rojo aka Jaromil, George Klissiaris, Evan Light, Ilias Marmaras, Monic Meisel, Jürgen Neumann, Radovan Misovic aka Rad0, Natacha Roussel, Andreas Unteidig, Danja Vasiliev, Christoph Wachter & Mathias Jud, and Stewart Ziff.

The Off-the-Cloud-Zone day event was a continuation of last year’s offline networks unite! panel and workshops. Which also originated from discussions on a mailing list called ‘off.networks’ with researchers, activists and artists working together around the idea of an offline network operating outside of the Internet. The talks concentrated on how over recent years there has been a growing scene of artists, hackers, and network practitioners, finding new ways to ask questions through their practices that offer alternatives in community networks, ad-hoc connectivity, and autonomous systems of sensing and data collecting.

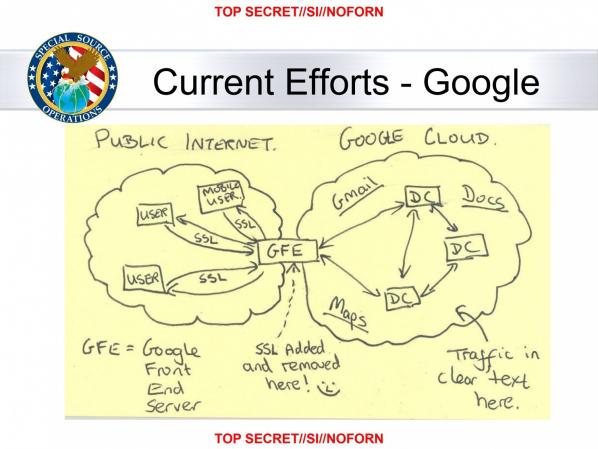

Disillusionment with the Internet has spread widely since 2013, when Edward Snowden the US whistleblower leaked information on numerous global surveillance programs. Many of these programs are run by the NSA and Five Eyes with the cooperation of telecommunication companies and European governments raising big questions about privacy and exploitation of our online (interaction) data. This concern is not only in relation to spying corporations, dodgy regimes and black hat hackers, but also our governments. “The idea of privacy has been flipped on its head. People don’t have to disclose their own information voluntarily anymore; it’s being taken from them regardless of their wishes.” [2] (Nowak 2015)

“The NSA’s principal tool to exploit the data links is a project called MUSCULAR, operated jointly with the agency’s British counterpart, the Government Communications Headquarters . From undisclosed interception points, the NSA and the GCHQ are copying entire data flows across fiber-optic cables that carry information among the data centers of the Silicon Valley giants.” [3] (Gellman and Soltani, 2013)

The above slide is from an NSA presentation on “Google Cloud Exploitation” from its MUSCULAR program. The sketch shows where the “Public Internet” meets the internal “Google Cloud” where user data resides. [4]

A legitimate concern for anyone wishing to read the contents of the leaked Snowden files, is that they will be spied upon as they do so. Evan Light has been working on finding a way around this problem, and at the Off-the-Cloud-Zone day event he presented his project Snowden Archive-in-a-Box. A stand-alone wifi network and web server that permits you to research all files leaked by Edward Snowden and subsequently published by the media. The purpose of the portable archive is to provide end-users with a secure off-line method to use its database without the threat of surveillance. Light says, usually the wifi network is open, but users do have the option to make their own wifi passwords and also choose their encryption standard.

Snowden Archive-in-a-Box is based on the PirateBox, originally created by David Darts who made his in order to distribute teaching materials to students without the hassle of email. It is based on a RaspberryPi 2 mini-computer and the Raspbian operating system. All the software is open-source and its most basic setup can run on one RaspberryPi. In his talk Light said that a more elaborate version would use high-quality battery packs and this adds power for autonomy, along with the wifi sniffer that is running on a secondary RaspberryPi and a flat-screen for playing back IP traffic. If you’re interested in building your own private, pirate Archive-in-a-Box, visit Light’s web site for instructions on how to.

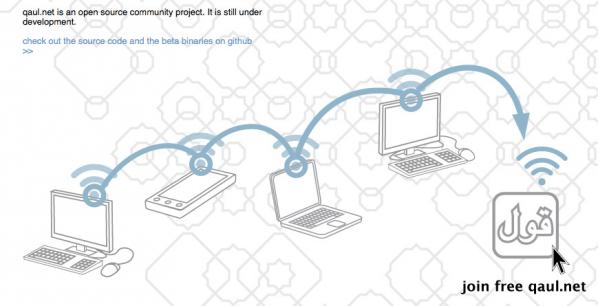

Christoph Wachter’s and Mathias Jud’s work, directly engages with refugees and asylum seeker’s social situations, policies, and the migrant crisis. They’ve worked together on participatory community projects since 2000 and have received many awards. For instance, take a look at their digital communications tool qaul.net which is designed to counteract communication blackouts. It has been used successfully in Egypt, Burma, and Tibet, and works as an alternative to already existing government and corporate controlled communication pathways. But, it also offers vital help when large power outages occur, especially in areas in the world suffering from natural disasters. The term qaul is Arabic and means ‘opinion, say, talk or word’. Qaul is pronounced like the English word ‘call’.

It creates a redundant, open communication code where wireless-enabled computers and mobile devices can directly initiate a fresh, unrestricted and spontaneous network. This includes the enabling of Chat, twitter functions and movie streaming, independent of Internet and cellular networks. It is also accessible to a growing Open Source Community who can modify it freely.

Wachter and Jud also discussed another project of theirs called “Can You Hear Me?”, a WLAN / WiFi mesh network with can antennas installed on the roofs of the Academy of Arts and the Swiss Embassy in Berlin, which was located in close proximity to NSA’s Secret Spy Hub. These makeshift antennas made of tin cans were obvious and visible for all to see. The Academy of Arts joined the project building a large antenna on the rooftop, situated exactly between the listening posts of the NSA and the GCHQ to enable people to directly address surveillance staff listening in. While installing the work they were observed in detail by a helicopter encircling overhead with a camera registering each and every move they made, and on the roof of the US Embassy, security officers patrolled.

“The antennas created an open and free Wi-Fi communication network in which anyone who wanted to would be able to participate using any Wi-Fi-enabled device without any hindrance, and be able to send messages to those listening on the frequencies that were being intercepted. Text messages, voice chat, file sharing — anything could be sent anonymously. And people did communicate. Over 15,000 messages were sent.” [5] (Jud 2015)

A the end of their presentation, they said that they will be implementing the same system at hotspots deployed in Greece by the end of the month. And I believe them. What I find refreshing with these two, is their can do attitude whilst dealing with political forces bigger than themselves. It also gives a positive message that anyone can get involved in these projects.

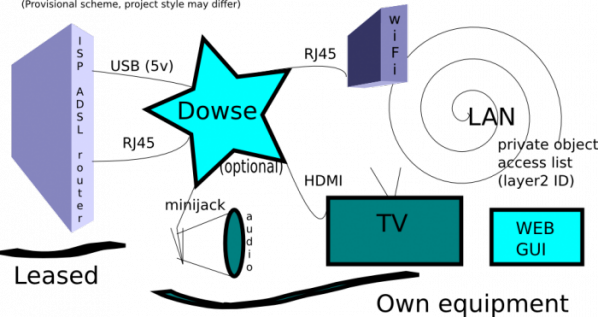

And then, it was the turn of the well known team at Dyne.org to discuss a project of theirs called Dowse, which is ‘The Privacy Hub for the Internet of Things’. They said (taking turns, there was about 5 of them) that the purpose of Dowse is to perceive and affect all devices in the local, networked sphere. As we push on into the age of the Internet of Things, in our homes everything will be linked up.

“Those bathroom scales and home thermostats already talk to our smartphones and in some cases think for themselves.” [6] (Nowak 2015)

As these ubiquitous computers communicate to each other even more, control over these multiple connections will be essential. We will need to know how to interact beyond the GUI interfaces and think about who has access to our private, common and public information. A whole load of extra information will be available without our consent.

Dowse was conceived in 2014 as a proof of concept white paper by Denis Rojo aka Jaromil. Early contributors to the white paper and its drafting process includes: Hellekin O. Wolf, Anatole Shaw, Juergen Neumann, Patrick R McDonald, Federico Bonelli, Julian Oliver, Henk Buursen, Tom Demeyer, Mieke van Heesewijk, Floris Kleemans and Rob van Kranenburg. I downloaded the white paper and is definitely worth reading.

The Dowse project aims to abide to the principles stated in the Critical Engineers Manifesto, (2011). Near the very end of the talk they announced to the audience an open call for artists and techies everywhere to get involved and jump into the project to see what it can do. This is a good idea. If there is no community to make or break platforms, hardware and software, then there is a limited dialogue around the possibilties of what a facility realistically might achieve. Not just that, they want artists to make art out of it. I know there are some pretty clever tech-minded geeks out there, who will in no doubt take on the challenge. However, once those who are not so literate in the medium are able to exploit the project, it will surely fly. It’s going to be interesting, because if you look at the 3rd point in the Critical Engineers Manifesto, it says “The Critical Engineer deconstructs and incites suspicion of rich user experiences.” I’m thinking, that this number 3 element needs to treated with caution. If they really wish to open it up to a diverse user base, to engage with its potentialities, creatively and practically; thus, allow new forms of social emancipation to evolve as ‘freedom with others’. There needs to be an active intent to avoid a glass ceiling based on technical know-how. It’s a promising project and I intend to explore it myself and see what it can do and will invite other people within Furtherfield’s own online, networks to join in and play, break, and create.

Our final entry is the Sarantaporo Project which is situated in the North of Greece. A village in the mountains just west of Mount Olympus in Central Greece close to Thessaloniki, Macedonia and Larisa. The country has been in recession for over 6 years now, and many communities have had to create alternative ways of working with each other in order to survive the crisis. Over this troubling period, new forms of grass-roots coexistence, solidarity and innovation have evolved. The Sarantaporo Project is an impressive example of how people can come together and experiment in imaginative ways and exploit physical and digital networks.

Even before the economic crisis the region was already hit by poverty, and with the added pressures of imposed Austerity measures, life got even tougher. All the young were leaving and then migrating to the cities or abroad. Before the project in Sarantaporo, there was no Internet nor digitally connected networks for local people to use. This situation contributed to the digital divide and made it difficult to work in a contemporary society, when so many others in the world have been using technology to support their civic, academic and business for so many years already.

“In Greece, where unemployment reaches 30% in all ages and genders, and among the youth overpasses 50%, immediate solution for the “social issue” is more than urgent.’ [7] (Marmaras).

“Besides maintaining the network in a DIWO (Do It With Others) manner, and creating an atmosphere of cooperation among far-flung communities that were previously strangers, the Sarantaporo network is incorporating different groups of people into the community, like Farmer’s Cooperatives and techies. It is also creating an intergenerational space for learning.” [9] (Bezdommy 2016)

To resolve this issue a group of friends decided to deal with this problem by setting up a community D.I.Y wireless network to provide free internet access to 15 villages in the municipality of Elassona. “Sarantaporo.gr is an open source wireless mesh networking system that relies greatly on voluntary work both for its development and maintenance. Some volunteers are involved in the project by simply installing an antenna on their roof. Others, more actively engaged with the project, are responsible for sustaining the network by hosting meetings and answering technical questions.” [8] (Kalessi 2014) The audience was presented with snippets from a film made by the filmmaking collective Personal Cinema, about the project. It was made so the story of Sarantaporo’s DIY wireless network gets a wider reach, and that others are also inspired to do similar projects themselves.

These projects are dedicated to creating socially grounded and engaged alternatives to the proprietorial, networked frameworks that currently dominate our communication behaviours. These proprietorial systems, whether they are digital or physical are untrustworthy, and control us in ways that reflect their top-down demands but not our common needs. This reflects a wider conversation about who owns our social contexts, our conversations, our fields of practice, the structures we use, the land, the cables, our history, and so on.

Looking at the state of the planet right now you’d be forgiven for betting on a future not far from the director Neill Blomkamp’s vision in the sci-fi movie Elysium where, in the year 2159, humanity is sharply divided between two classes of people: the ultra-rich whom live aboard a luxurious space station called Elysium, and the rest who live a hardscrabble existence in Earth’s ruins. However, in the Off-the-Cloud-Zone talks we encountered an ecology of strategies to protect our own indegenous cultures from the crush of neo-liberalism, we felt part of a grounded movement discovering new conversations and new methodologies that may provide some protection against future colonisation. Perhaps there is a chance, we can build and rebuild stronger relations with each other, beyond: privilege, nation, status, gender, class, race, religion, and career.

The festival this year was less structured and more nuanced than usual. It gave conversation a greater role and a deeper social context, and opened up the process for the many to connect with the ideas being explored. The whole affair seemed to be slowed down and less caught up in the hyper-macho trappings of accelerationism. It seemed less neurotic and spending less effort to impress. I’m sure, next year, on it’s 30th anniversary, all will be sharp and amazing. However, I liked this less glossy, more messy version of Transmediale and I hope it manages to impress the wrong people again, and again.

The term DIWO – Do It With Others was first defined in 2006 on Rosalind – Upstart New Media Art Lexicon1 It extended the DIY Do-It-Yourself ethos of early net art, punk & Situationism, towards a more collaborative approach, using the Internet as an experimental artistic medium and distribution system to foment grass-roots creativity. Even before it was defined it underpinned everything Furtherfield has ever done.

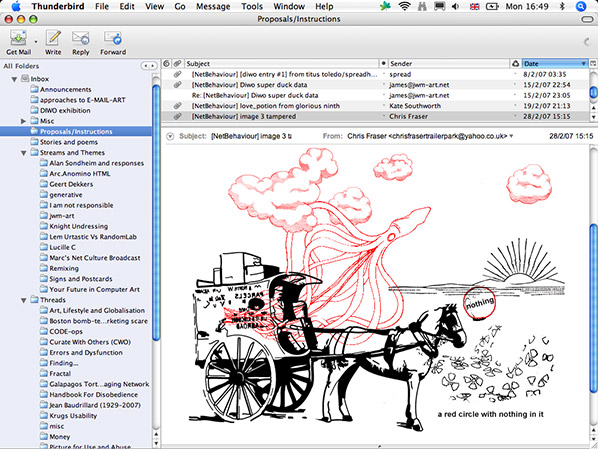

The first DIWO Email Art project started with an open call to the email list Netbehaviour, February 1st 2007. The call drew on the Mail Art tradition proposing to bypass curatorial restrictions to promote imaginative exchange between artists and audiences on their own terms.

“Peers connect, communicate and collaborate, creating controversies, structures and a shared grassroots culture, through both digital online networks and physical environments.”2

Participants worked ‘across time zones and geographic and cultural distances with digital images, audio, text, code and software. They created streams of art-data, art-surveillance, instructions and proposals in relay, producing multiple threads and mash-ups.’3. Co-curated using VOIP and webcams the exhibition at HTTP Gallery displayed every contribution in an email inbox, alongside an installation of prints of every image, and a running copy of every video and audio file submitted.4 Every post to the list, until April 1st, was considered an artwork – or part of a larger, collective artwork – for the DIWO project.

DIWO at the Dark Mountain was the second DIWO email art exhibition instigated by Furtherfield and the Dark Mountain Project in 2010. It took ecological collapse as its subject and the need for new stories, systems and infrastructures as its premise. This project generated intense controversies among participants. Again, considered part of the artwork, the details of debates were re-enacted for gallery visitors in a live performance at the opening event. In addition to the networked, live-streamed co-curation event, and the performance, this exhibition closed with a disassembly event in which gallery visitors demounted all physical works and redistributed them via snail mail to anyone they knew.5

In recent years other individuals and have taken DIWO as the inspiration for their own projects. Some changed its meaning. For instance, Cory Janssen’s definition of DIWO for Technopedia, does away with the art, and collaboration across difference. We think that what he describes is just plain and simple Crowdsourcing.6 Others maintain the adventurous and emancipatory spirit. For instance, in 2012 Pixelache the Helsinki-based transdisciplinary platform for experimental art, design, research and activism took DIWO as the theme for its annual festival.7 Whatever the starting point we always welcome invitations to DIWO!

Notes

Do It With Others (DIWO): contributory media in the Furtherfield Neighbourhood by Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett, Furtherfield. From Coding Cultures, 2007. Editor: Francesca Da Rimini. Published by d/lux, Lilyfield NSW Australia. Available at Foam (pdf) here.

Do It With Others (DIWO) – E-Mail Art in Context by Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett, 2008. Curediting, Vague Terrain. Available here.

DIWO (Do-It-With-Others): Artistic co-creation as a decentralized method of peer empowerment in today’s multitude by Marc Garrett, 2013, published by SEAD: White Papers. Available here.

DIWO: Do It With Others – No Ecology without Social Ecology, by Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett. From Remediating the Social, 2012. Editor: Simon Biggs University of Edinburgh. Published by Electronic Literature as a Model for Creativity and Innovation in Practice, University of Bergen, Norway. Available here.

More DIWO references

Don’t DIY, DIWO — a VOD case study with Anatomy of a Love Seen, by Peter Gerard. Published on May 7, 2015 on the Vimeo staff blog.

Featured image: Image from Fab Lab (fabrication laboratory), small-scale workshop offering digital fabrication

There is currently a significant amount of interest in the relationship between free and Open Source practices in art and the aim of this report is to map out some of these shifting relationships in contemporary models of education both online and offline. The recent expansion of so-called ‘free culture’ has contributed to placing the debate over authorship, ownership and licensing of the artwork at the centre of artistic production. Crucially, the transformation of art in the age of global culture and the consequent move from autonomous art objects into cultural artworks and services, has resulted in the emergence of three visible tendencies: 1) free/Open/Source software as artistic-pedagogical method, 2) the critical emancipation of the self-education movement and 3) the digitisation of art education practices into Open Source packages of cognitive labour.

One possible way to navigate this complex ideological terrain is the conciliatory term free/libre/Open Source software (floss), seeing it as “part of an emerging transdisciplinary field that deals with different forms of openness.” [1] At the heart of the debate is the political distinction between the Free Software Foundation[2] and the Open Source Initiative.[3] The ‘copyleft’ attitude (free software movement) asserts four freedoms for software: free from restriction, free to share and copy, free to learn and adapt, free to work with others.[4] The Open Source definition,[5] on the other hand, in spite of apparent similarities, has developed into flexible arrangements such as the Creative Commons licenses[vi][6], some of which restrict these freedoms when applied to media/cultural works and publications, not allowing for derivative artwork or its commercial use under specific license combinations.[7]

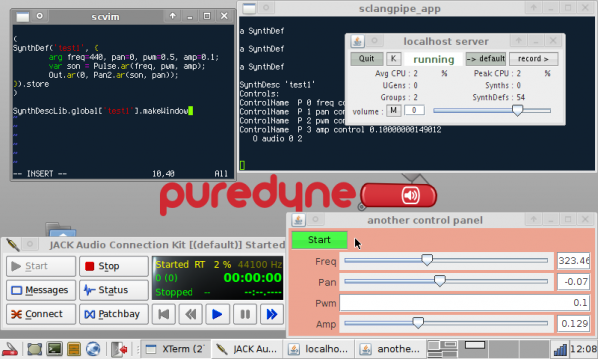

A number of projects, such as the pure:dyne[8] – GNU/Linux operating system for live audio visual processing and teaching – are, however, fully identified with the principles of free software. They have emerged from artists’ collectives whose relationship to art education is informally associated with sharing spaces, the hacklabs and free media labs where they run workshops and introduce participants to the use of free digital art tools. [9] Their mode of production is centred on ‘live code’ and feature two essential characteristics: 1) collaborative- relying on large-scale public participation and 2) distributive- offering the tools and the process notes (notation) to empower the others to carry on the work on their own.[10] This philosophy implies that the artistic performance of the work is complemented by a set of pedagogical approaches associated with the enabling of production by others. [11]

The movement for free education has gained greater relevance as a result of the global financial crisis and the battle for control of university fees.[12] In this context, art education has been developing into an artistic project while also providing an emancipatory movement reacting against dominant forms of institutionalised knowledge production. Within this movement, the role of free/open technology has been central in the mediation of self-education as a social movement.

On the one hand, artists –freelancers, sometimes temporarily/precariously plugged into educational institutions whilst working as teachers, others times as workshop facilitators in free access spaces– have opened up their classrooms to the environment of the read/write web, and with their students-collaborators, have produced and shared in wikis, blogs and Second Life, art and education resources that make an increasingly significant contribution to a larger body of knowledge that is the web. [13] Wikiversity is a model of this confluence of self-education movements and open online education.[14]

In parallel with the above-mentioned tendencies of online systems, numerous critical projects have appeared that are associated with the reclamation of space that occurs as artists have found themselves at the forefront of self-organised and self-managed self-education projects.[15] Some have happened side-by-side with the reclamation and occupation of spaces such as the Temporary School of Thought[16] and the Really Free School.[17] Part of these groups activity is the establishment of a free programme of workshops on topics that can range from free software tools to Ivan Illich and Deschooling Society.[18] Others that make opportunistic incursions into the artworld such as the Bruce High Quality Foundation University,[19] the Future Academy[20] or Unitednationsplaza,[21] are platforms for experimental art as research, investigating the production of knowledge that occurs when art education itself becomes artwork or exhibition.[22]

While the debate on free education has been enjoying significant visibility, the Higher Education sector has also joined in. A few recent initiatives have supported universities of the arts developing virtual learning environments and providing access to open education resources (OERs). This is the case with the JISC Practising Open Education Project (2010-2011)[23] with six art, design and media departments in UK universities. A number of these OERs include art work (photographs, drawings and videos), but the majority are art theory, mostly research papers, dissertations and art education research documents produced by artists-teachers-researchers as part of their continuing professional development. These are distributed with Creative Commons licenses with varying degrees of freedom, but rarely have the ‘copyleft’ attitude that has been associated with the free software.

Such an enterprise can be interpreted in the light of current debates in the fields of immaterial labour and cognitive capitalism revealing that whilst (digital) art becomes postproduction, art education is being packaged into open resources that circulate as part of the capitalist system, and become central to the new eLearning/networked economies. In addition to filling a gap in subject-specific open resources, this raises the question: why is the free and the open so popular in contemporary art education? A cynical hypothesis is that art education, by declaring itself as a type of production of knowledge, attempts to gain a new legitimacy, in the bureaucratised global knowledge market. The other possibility is that in the face of such a doomed scenario, art education searches for new possibilities beyond pure commercialism, reclaiming access through “contingencies of opening and mobility of cognitive packages beyond confines of ownership.” [24]

1. Floss as artistic –pedagogical method

The Digital Artists Handbook

The digital handbook, published by the arts organisation folly and artists’ collective GOTO10 in 2008, aims to give artists information about the available tools and the practicalities related to Free/Libre Open Source Software and Content such as collaborative development and licenses.

FLOSS+Art

This book edited by Aymeric Mansoux and Marloes de Valk in 2008 reflects critically on the growing relationship between Free Software ideology, open content and digital art. With contributions by: Fabianne Balvedi, Florian Cramer, Sher Doruff, Nancy Mauro Flude, Olga Goriunova, Dave Griffiths, Ross Harley, Martin Howse, Shahee Ilyas, Ricardo Lafuente, Ivan Monroy Lopez, Thor Magnusson, Alex McLean, Rhea Myers, Alejandra Maria Perez Nuñez, Eleonora Oreggia, oRx-qX, Julien Ottavi, Michael van Schaik, Femke Snelting, Pedro Soler, Hans Christoph Steiner, Prodromos Tsiavos, Simon Yuill. Available both in print and as torrent download

Technology Will Save Us

The project by Daniel Hirschman & Bethany Koby is a haberdashery for technology and alternative education space dedicated to helping people to produce and not just consume technology.

Openlab

Openlab Workshops was started by artist and educator Evan Raskob in mid-2009 to fulfil the need for practical education about digital art and technology. Floss workshops are developed and taught by working artists and media practitioners, giving participants direct access to practical experience.

GOTO10

GOTO10 is an artists’ collective that organises floss workshops on subjects such as Pure Data, Linux audio tools, physical computing, SuperCollider, puredyne, RFID, Audio Signal Processing, and other related areas of practice.

UpStage

UpStage is an Open Source platform for cyberformance and education: remote performers combine images, animations, audio, web cams, text and drawing in real-time for an online audience. Initiated by the globally dispersed performance troupe Avatar Body Collision, it runs the annual Upstage festival, open to proposals.

2. Self-organised and self-managed art education

Really Free School

Free school based in a squatted London pub. “Amidst the rising fees and mounting pressure for ‘success’, we value knowledge in a different currency; one that everyone can afford to trade. In this school, skills are swapped and information shared, culture cannot be bought or sold. Here is an autonomous space to find each other, to gain momentum, to cross-pollinate ideas and actions.” (Communiqué #1)

Bruce High Quality Foundation University

A free university project set up by NY-based artists’ collective The Bruce High Quality Foundation. “We believe in the artistically educational possibilities of collaboration. Collaboration, as we mean it, means a group of concerned people come together to hash out ideas, try to figure out the world around them, and try to take some agency within its future. That’s the why and how of The Bruce High Quality Foundation. BHQFU is an attempt to extend the benefits of this collaborative model to a wider number of people.”

Unitednationsplaza

A temporary, experimental school in Berlin, initiated by Anton Vidokle following the cancellation of Manifesta 6 on Cyprus, in 2006. Developed in collaboration with Boris Groys, Liam Gillick, Hatasha Sadr Haghighian, Nikolaus Hirsch, Martha Rosler, Walid Raad, Jalal Toufic and Tirdad Zolghadr, the project travelled to Mexico City (2008) and, eventually, to New York City under the name Night School (2008-2009) at the New Museum. Its program was organized around a number of public seminars, most of which are now available in their entirety online.

FOSSter creative Learning

Lesson plans that can be used in the art classroom, developed by The FOSSter Creativity Team, a group of students of the University of the Arts (USA)

3. Open Source Repositories

University of the Arts institutional OER repository

University for the Creative Arts institutional OER repository

VADS (Visual Arts Data Service) A collection of over 100,000 art and design images that are freely available and copyright cleared for use in learning, teaching and research in the UK.

OER Commons A repository of materials about teaching, technology, research in the emerging field of Open Education. Art materials at OER commons.

You can find paula’s original article on Collaboration and Freedom – The World of Free and Open Source Art http://p2pfoundation.net/World_of_Free_and_Open_Source_Art

This article is part of the Furtherfield collection commissioned by Arts Council England for Thinking Digital. 2011

DIWO (Do-It-With-Others): Origin, Art & Social Context, is an update on Furtherfield’s artistic and cultural practice of DIWO. In light of the emergence of DIWO in other fields of creative practices, and its ever growing popularity. We reconnect to the original reasons of why Furtherfield introduced and shared the concept of DIWO to the world in the first place.

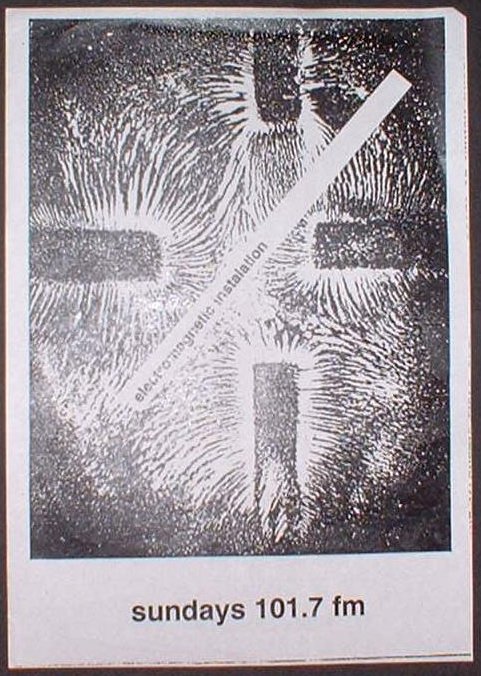

We revisit early historical influences from 60s and 70s Mail Art, Fluxus, Situationism, Activism and D.I.Y culture; early adventures/projects with pirate radio, a mass networked email art, and (snail mail) mail art’, street art project by Furtherfield back in 1999; to what DIWO is now today, part of a more extensive, and networked grass roots movement around the world.

It also draws upon links to P2P (peer to peer) culture, the free and open source movement. Each of these cultural activities are seen as equal, peer relations, and re-hacks an intuitive space away from traditional hegemonies and their established hierarchies.

It re-emphasize it’s core motives, as a critique against mainstream media and the traditional art establishment’s control over our art history and contemporary art imaginations. It challenges the non-critical nature of artists’ complicit desire in conforming to celebrity status and fitting into stereotypical behaviours informed by hegemony, and cultural dominance. Furthefield’s intention for DIWO has always been a about individual and collective emancipation, and this story is about what this means now…

Before we jump into Furtherfield’s first DIWO project it’s worth mentioning an earlier historical reference to Bristol city (UK) and pirate radio. I, and a dedicated group of individuals were interested in finding alternative avenues for community and collective expression. We set up various pirate radio stations in Bristol, the longest running was ‘Electro Magnetic Installation (EMI)’ pirate radio station, which ran for over 18 months, broadcasting to greater Bristol every weekend ending in 1991. We changed our location for each broadcast and disseminated disinformation to confuse the authorities. We used a home built 20 Watt stereo FM transmitter and antenna. All submitted material was provided on audio tape for broadcast, the quality or quantity was not edited and everyone interested had their sound art, cut up mixes, music and words heard by many. We had to close down after a while due to surveillance stress. We did re-emerge with other pirate radio broadcasts briefly, under various different names. An even earlier one, which we took over for a while was called ‘savage but tender’ in 1989.

Bristol in the late 80s and early 90s was a dynamic and exciting place to be. Especially if one was creative and also interested in alternative ways of thinking and living. Independent culture was thriving. It was back in the 70s when Bristol’s radical spirit of creative and political autonomy was first forged. Post punk bands such as the Pop Group, Rip Rig & Panic, spread their own influential ethos of being creative and activist as a way of life. Advocating everyday people could be different, be independent thinkers and question the validity of the established norm. This flexible blueprint of being socially conscious in an imaginative way influenced a huge mixture of genres for years to come. Breaking down the borders between the audience and the musicians playing was a legacy handed on down from punk. This includes building your own record label, setting up your own pirate radio station, self publishing and other ventures.

Furtherfield’s first collective (yet unofficial) DIWO experience was at the Watermans Art Centre, London in 1999. We were asked to present a project which reflected the free and liberated spirit of our networked on-line community and its creative culture. The name of the project was called “Pasteups@Watermans Art Centre”, not DIWO. It had all the features of DIWO, such as using email as art, and the traditional postal services (snail mail) as part of its distribtion process. From all over the world people were invited to send images and texts which were then enlarged into a mass of photocopied posters.

On Sunday 10th October 1999 all the hoardings and wall spaces in the streets around the Watermans Art Centre were blitzed with Pasteups. There was no selection of what should be taken out or left in, everything was shown. They were put up by the Furtherfield crew and who ever wished to help out. Some of those whom took part were also local to the area. The people working in the centre reacted as if they were being over taken from a dark external force, and the passing public were expressing a mixture of emotions – enjoyment, surprise, interest, confusion, distaste and annoyance. It challenged the ideal of art having to be a rigid divide and rule of amateur vs professional, using the Internet and the physicalness of the Watermans Art Centre’s building, inside and outside. The streets were used as a shared canvas to fill our collective, imaginative expressions at that time.

“”… the role of the artist today has to be to push back at existing infrastructures, claim agency and share the tools with others to reclaim, shape and hack these contexts in which culture is created.” [1] (Catlow 2010)

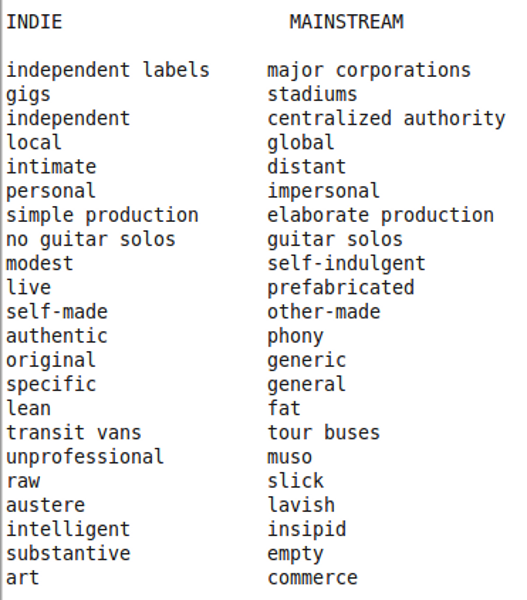

In her study ‘Empire of Dirt: The Aesthetics and Rituals of British Indie Music (Music Culture)’, Dr. Wendy Fonarow [2] investigated the UK’s indie music scene and its culture from the early 1990s to present. Below Fonarow presents the differences between mainstream and independent music culture. Contrasts are mapped out in Lévi-Straussian fashion:

“Indie itself in relation to the mainstream as an opositional force combating the dominant hegemony of modern urban life. Any band that is seen as “chipping away at the facade of of corporate pop homogeny” (Melody Maker, April 1995) is a positive addition to the indie fellowship.”[3] (Fonarow 2006)

There are similar terms above as there is with critical practices in Media Art culture, Free and Open Source culture, activism and hacktivism, and with concepts behind DIWO. Words such as self-made, independent, raw and substantive offer strong relational ties to what we feel ourselves is essential for a thriving, discerning and critically aware process, of an unfettered state of discovering, and how to do things without conforming to top-down protocols, individually or collaboratively.

“To be an artist is to contend with the present, and there are not many other careers that afford the freedom to radically examine life and society. To put it bluntly, if artists are studying and writing more about politics, culture, and education, it’s probably a reflection of the unprecedented dysfunctionality of the societies in which they live.” [4] (Deck 2005)

When considering an art context, critical thinking on the social nuances, social and relational variants introduce possibilities for a deeper understanding of the meaning of a work and its place in the wolrd. Not only in respect of the quality of an artwork in its own right, but it also introduces consideration concerning value. Value comes out of dialogue whilst the work is put into motion, as the process occurs as well as when it reaches its final stage of being seen – it’s birth is always messy, but this process gives us the rich nutriants, the substance.

By recognising resonances that lurk between art and culture and our own connections with these elements; as we make things with others different core values come into play. This is where knowledge of how an artwork and its meaning communicates beyond the artwork itself; to and with others, linking up to the ever changing rhythms dominating society. All this, also depends on the context of how and where a work is seen. An artwork and where it is seen declares the artists’ relationship with other structures, infrastructures and networks, whether this be physical or based on-line. This informs us about the artists’ personal concepts, attitudes and social values. These attributes become part of the work; its story and part of its essence and its reasons for existing in the first place.

Whoever controls our art – controls our connection, relationship and imaginative experience and discourse around it. The frameworks and conditions where art is accessed, seen and discussed is significantly linked to representation and ownership. Socially and culturally, this process of abiding by specific rules and protocols defines who and what is worth consideration and acceptance. For art to be accepted within these ‘traditional’ frameworks a dialogue reflecting its status around a particular type of function kicks into place, it must adhere to certain requirements. Whether it is technological or using traditional art making skills the art itself must in some way conform to specific protocols before it can be allowed into the outer regions of ‘officially’ condoned culture. This process adds merit to the creative venture itself and feeds a systemic demand based around innovation in a competitive marketplace. If an iindividual or an collective does not abide by these dominating rules then they will not be seen in these frameworks. DIWO allows one to venture with many, in playful scenarios of mutual experience and interdependence, freeing up the trappings of ‘officially’ defined protocols and frameworks, governing our behaviours. This does not mean that there are no rules, it merely means that we have a more relationally informed understanding of how to work with others. Structures and aims are decided in different terms mutually.

DIWO is playful re-interpretation and fruition of some of the principles and reasons that Furtherfield was originally founded, back in 96-97. We had experienced as artists in the 80s and well into the 90s, a UK art culture mainly dominated by the marketing strategies of Saatchi and Saatchi. The same company was responsible for the successful promotion of the Conservative Party (and conservative culture) that had led to the election win of the Thatcher government in 1979. We felt that it was time to make a stance against these neoliberalist heavies controlling the art scene and our every day culture. Our aim was to move away from the typically established, sociallly engineered aspects of art culture where false credence was given to a few individuals over many others, based on their personalities alongside their depoliticized artworks.

“Furtherfield’s roots extend back through the resurgence of the national art market in the 1980s, to the angry reactions against Thatcher and Major’s Britain, to the incandescence of France in May 1968, and back again to earlier intercontinental dialogues connecting artists, musicians, writers, and audiences co-creating “intermedial” experiences.” [5] (Da Rimini 2010)

Our move away from this was to create pro-active alternatives, with social hacks, bypassing the marketing myth of the ‘genius’ as a product via the usually distracting diversions, and top-down imposed spectacles based on privilege and hegemony. Recently an article written by John A. Walker on the artdesigncafé web site, disucussed how art culture is still haunted by the power of Charles Saatchi.

“Arguably, as an art collector Charles Saatchi has become a brand in his own right—when he buys art works they and the artists who created them are immediately branded.” [6] (Walker 2010)

BritArt’s dominance of the late 80s and 90s UK art world dis-empowered the majority of British artists, and Smothered other artistic discourse by fuelling a competitive and divisive attitude for a shrinking public platform for the representation of their own work. Stewart Home proposes that the YBA movement’s evolving presence in art culture fits within the discourse of totalitarian art.

“The cult of the personality is, of course, a central element in all totalitarian art. While both fascism and democracy are variants on the capitalist mode of economic organisation, the former adopts the political orator as its exalted embodiment of the ‘great man,’ while the latter opts for the artist. This distinction is crucial if one is to understand how the yBa is situated within the evolving discourse of totalitarian art.” [7] (Home 1996)

By questioning the myths that dominate our actions we then become more empowered and confident to collaborate with others. We can only rediscover these inner creative kernals by critiquing the infrastructures dominating our behaviours. Many artists have and do conform to mainstream art world rules. This closes down space for a wider dialogue and experience for art practice to expand its possible horizons, beyond a handed down, hermetically sealed set of distant processes. When experimenting with alternative approaches of imaginative engagement a different set of values arrive. Through this we unearth things about ourselves which were already there but were trapped before by the mechanisms and mannerisms of mainstream culture and its dominant values.

DIWO (Do It With Others) is inspired by DIY culture and cultural (or social) hacking. Extending the DIY ethos with a fluid mix of early net art, Fluxus antics, Situationism and tactical media manoeuvres (motivated by curiosity, activism and precision) towards a more collaborative approach. Peers connect, communicate and collaborate, creating controversies, structures and a shared grass roots culture, through both digital online networks and physical environments. Stringly influenced by Mail Art projects of the 60s, 70s and 80s demonstrated by Fluxus artists’ with a common disregard for the distinctions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art and a disdain for what they saw as the elitist gate-keeping of the ‘high’ art world.

The term DIWO OR D.I.W.O, “Do It With Others” was first used on Furtherfield’s collaborative project ‘Rosalind’ (http://www.furtherfield.org/get-involved/lexicon). An upstart new media art lexicon, born in 2004. DIWO was officially termed here in 2006 (http://www.furtherfield.org/lexicon/diwo)

“It is in the use of the postal system, of artists’ stamps and of the rubber stamp that Nouveaux Realisme made the first gestures toward correspondence art and toward mail art.” [8] (Friedman 1995)

Mail Art is a useful way to bypass curatorial restrictions for an imaginative exchange on your own terms. With DIWO projects we’ve used both email and snail mail. Later, we will return to the subject of email art and how it has been used for collective distribution and collaborative art acitivies; but also, how it can act as a remixing tool and an art piece in its own right on-line and in a physical, exhibiting environment.

“[…] many Fluxus works were designed specifically for use in the post and so the true birth of correspondence art can arguably be attributed to Fluxus artists.” [9] (Blah Mail Art Library)

Many consider George Maciunas was to Fluxus, what Guy Debord was to Situationism. Maciunas set up the first Fluxus Festival in Weisbaden in Germany, 1962. In 1963, he wrote the Fluxus Manifesto in 1963 as a fight against traditional and Establishment art movements. In a conversation with Yoko Ono in 1961, they discussed the term and meaning of Fluxus. Showing Ono the word from a large dictionary he pointed to ‘flushing’.

“”Like toilet flushing!”, he said laughing, thinking it was a good name for the movement. “This is the name”, he said. I just shrugged my shoulders in my mind.” [10] (Ono 2008)

“The purpose of mail art, an activity shared by many artists throughout the world, is to establish an aesthetical communication between artists and common people in every corner of the globe, to divulge their work outside the structures of the art market and outside the traditional venues and institutions: a free communication in which words and signs, texts and colours act like instruments for a direct and immediate interaction.” [11] (Parmesani 1977)

Maciunas’s intentions and ideas are strongly based on creative autonomy. DIWO in the 21st Century explores its own position of (social) grounded reasoning and creative chaos. In contrast to the usual, standardized and bureaucratic implimentations by an increasingly banal, neoliberal elite controlling our art, education, media and economies.

“[…] art has become too narcissistic and self-referential and divorced from social life. I see a new form of participatory art emerging, in which artists engage with communities and their concerns, and explore issues with their added aesthetic concerns” [12] (Bauwens 2010)

“Marshall McLuhan once suggested that ‘art was a distant early warning system that can always tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it'” [13] (Gere 2002) The infrastructural tendencies that occur when ‘the many’ practice DIWO; informs us we are in a constant process which redefines the role of the individual, and our notions of centralized power and behaviour. This process also presents us with critical questions around the value of art as scarcity. In moving away from our emotional attachment with the socially engineered dependencies based on consumer led forms of scarcity and desire, we then change the defaults. If we change the defaults we change the rules, no longer besieged by top-down defaults and open to more intuitive and relational contexts.

DIWO proposes in its fluid and sensual action of immediacy; situations where anyone can play and initiate collaborative and autonomous art. It is a radical creativity, asking questions through process and peer engagement, loosening infrastructural ties and frameworks as it occurs.

DIWO is a contemporary way of collaborating and exploiting the advantages of living in the Internet age. By drawing on past experiences with pirate radio, historical inspirations from Punk, with its productive move towards independent and grass roots music culture, as well as learning from Fluxus and the Situationists, and peer 2 peer methodologies; we transform our selves into being closer to a more inclusive commons. We transform our relationship with art and with others into a situation of shared legacy and emancipation.

“The network is designed to withstand almost any degree of destruction to individual components without loss of end-to-end communications. Since each computer could be connected to one or more other computers, Baran assumed that any link of the network could fail at any time, and the network therefore had no central control or administration (see the lower scheme).” [14] (Dalakov 2011)

Even though the web and DIWO possess different qualities they are both forms of commons. They both belong to the same digital complexity, and involve us connecting with each other. They are both open systems for human and technological engagement. DIWO rests naturally within these frameworks much like other digital art works or platforms and related behaviours, but possess key differences. If we consider the functions and structures of Facebook, Google, MySpace, itunes and now Delicious, they are all centralized meta-platforms, appropriating as much users as possible to repeatedly return to the same place.

“We see social media further accelerating the McLifestyle, while at the same time presenting itself as a channel to relieve the tension piling up in our comfort prisons.” [15] (Lovink 2012)

These meta-platfroms are closed systems. Not, necessarily closed as in meaning ‘you cannot come in’, but closed to others if you consider their motives and ‘acted out’ values, exploiting human interaction and their uploaded material, and openly ‘given’ data-information. These centralized meta-platforms close choices down through rules of ownership of personal data, as well as introducing more traditional standards of hierarchy, and limits one’s view and potential experience of the Internet.

Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron saw this curious dichotomy way back in 1995. On one hand we had the dynamic energy of sixties libertarian idealism and then on the other, a powerful hyper-capitalist drive, Barbrook and Cameron termed this contradiction as ‘The Californian Ideology’. “Across the world, the Californian Ideology has been embraced as an optimistic and emancipatory form of technological determinism. Yet, this utopian fantasy of the West Coast depends upon its blindness towards – and dependence on – the social and racial polarisation of the society from which it was born. Despite its radical rhetoric, the Californian Ideology is ultimately pessimistic about real social change.” [16] (Barbrook and Cameron 1995)

Instead of submitting to an imperious process of allowing bland interaction own our behaviours; we propose an engagement where we can be more conscious and in control by exploiting further the real potential of the networks before us.

“We are not going to demand anything. We are not going to ask for anything. We are going to take. We are going to occupy.”[17] (RTS 1997)

Just like Reclaim the Streets which was an anti-car direct action movement seizing roads to prevent cars from being able to access them. Filling up public areas with thousands of bikes and using street parties as part of the political protest. We can loosen the gaze and spectacle of these propriety, meta-platforms and their dominance of our actions with others on the Internet. DIWO, is a way of thinking and acting differently, not an absolutist ‘technologically determined’ factor, but a thing of many things, and leans more towards a kind of social activism going as far back as The Diggers:

“The Diggers [or ‘True Levellers’] were led by William Everard who had served in the New Model Army. As the name implies, the diggers aimed to use the earth to reclaim the freedom that they felt had been lost partly through the Norman Conquest; by seizing the land and owning it ‘in common’ they would challenge what they considered to be the slavery of property. They were opposed to the use of force and believed that they could create a classless society simply through seizing land and holding it in the ‘common good’.” [18] (Fox)

Three elements pull DIWO together as a functioning whole, which can mutute according to a theme, situation or project. These three contemporary forms of (potential) commons mainly include; the ecological – the social – and the networks we use. By appropriating these three ‘possible’ processes of being with others; combined, they introduce and enhance potential for an autonomous and artistic process to thrive, further than the limitations of any single or centralized point of presence. It brings about small societal change, as long as we are conscious of the social nuances needed for a genuine and critically engaged, mutual collaboration.

“Online creation communities could be seen as a sign of reinforcement of the role of civil society and make the space of the public debate more participative. In this regard, the Internet has been seen as a medium capable of fostering new public spheres since it disseminates alternative information and creates alternativ (semi) public spaces for discussion.” [19] (Morell 2009)

In accordance with Mail Art tradition, DIWO began with an open-call to the Netbehaviour email list on 1st February 2007. The exhibition was at our older venue the HTTP Gallery, opening at the beginning of March. Every post to the list until 1st April was considered an artwork – or part of a larger collective artwork for the DIWO project. Participants worked across time zones, geographical and cultural distances with digital images, audio, text, code and software; they worked to create streams of art-data, art-surveillance, instructions and proposals, and in relay to produce threads and mash-ups.

One example of a work which exploited the data-steams of continual flow while over a hundred individuals participated and collaborated in DIWO in 2007, was X-ARN.org (Gregoire Cliquet, Laurent Neyssensas and Yann le Guennec). By using the dynamic exchange of the Netbehaviour email list as reliable exchange of regualr content, the net art group were able to perform their particular and unique processes of interaction, or intervention. It had no specific title, it was literally documenting the list’s networkked behaviour, and there were many of these networked visualizations made. They experimented with the net-specific aspects of DIWO’s mass artistic activity, forming digital mappings of this collected data or data-streams in ‘real-time’, as it all happened.

![[ARN / DIWO-Betatests 2007]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/attachment3.png)

Some also participated in the experimental networked curation of the exhibition, facilitated by web cams, public IRC and VOIP technology. This co-curation event, or Curate With Others (CWO), as it was retroactively named, took place a week before the gallery opening. All subscribers to the NetBehaviour list were invited to contribute to the curation of the exhibition either by viewing the gallery floor plan and posting suggestions to the list or by taking part in the event; attending the gallery or joining the online meeting. Information about how to join the online event was posted to the list. During this event the spirit and philosophy of DIWO E-mail-Art were discussed, the deluge of diverse contributions by about a 100 people were reviewed, plinths, monitors and a drawing machine.

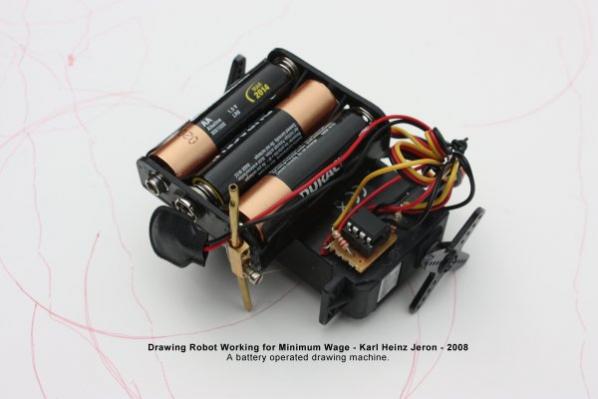

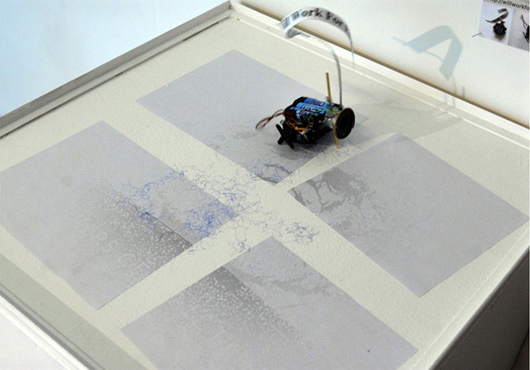

“The ‘Will Work For Food’ happening deals with the desire to find a new definition for labour and the act of working.” [20] (Jeron 2007)

Karl Heinz Jeron’s drawing machine was a vehicle equipped with a ballpen run by rechargable batteries, and when turned on created random drawings. Jeron’s machine was not switched on, unless he received gifts in the post such as chocolates or any other form of economic support. After (thankfully) receiving various contributions in the post the image supplied by Jeron of Karl Marx would gradually be scribbled over.

This section of the Article is an edited version of a collaborative text by Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett. Originally published on Vague Terrain in 2008. [21]

Present in the flesh were the Furtherfield.org crew and James Morris (regular, esteemed DIWO contributor).

Frederik Lesage manned the Public IRC and, as ‘DIWOchatbod’, who documented the conversation in the gallery for the benefit of those online co-curators who had trouble logging into Skype. Through the afternoon the online event was visited by eight people. The CWO event determined the format of the DIWO exhibition and the Furtherfield.org crew was charged with installing it. So, about approxximately 15 individuals on the day co-curated the setting up of the exhibition. Afterwards we informed everyone on the Netbeahviour list for any last minute details and suggestions and then continued with everything.

(Floorplan of Do It With Others (DIWO) at HTTP-Gallery, London. 2007)

The centerpiece of the exhibition was an e-mailbox containing all submissions; sorted and categorised for visitors to explore and redistribute by clicking ‘Forward Mail’. Streams and Themes displayed images, texts, sounds, code, and movies, primarily by single contributors (human and machine) as well as collections of themed posts or particular kinds of activity). Threads contained series of dialogic emails whose senders were remixing images, movies and code, most often in action and response). Other categories included Proposals and Instructions and Approaches to E-Mail Art.

(DIWO curated emailbox displaying image 3 tampered, posted by Chris Fraser 28/02/07)

Many of the themed folders and subfolders had their corollaries in the physical space of the gallery in the form of wiggly overlapping streams of printed images, pinned to the walls. Threads were represented by scrolls; one post after another in chronological order. A TV ran a video compilation, a sound compilation was played over four speakers, and two installation works were devised especially for the space. Karl Heinz Jeron’s ‘Will Work for Food’ and a print/projection mashup by Thomson and Craighead and Michael Szpakowski.

(Visitor to DIWO E-Mail Art at HTTP Gallery explores the DIWO email box. 2007. Image by Pau Ross)

All categories were liberally interspersed with off-topic discussion, tangents and conversational splurges so one challenge for co-curators was to reveal the currents of meaning, and emerging themes within the torrents of different kinds of data, process and behaviour. Another challenge was find a way to convey the insider’s – that is the sender’s and the recipient’s- experience of the work. These works then were made with a collective recipient in mind; subscribers to the Netbehaviour mailing list. This is a diverse group of people, artists, musicians, poets, thinkers, programmers (ranging from new-comers to old-hands) with varying familiarity with and interest in different aspects of netiquette and the rules of exchange and collaboration. This is reflected in the range of approaches, interactions and content produced. Before DIWO, extensive press releases were posted to different email lists, and online art platforms to join the Netbehaviour list to collaborate on the project.

(Lem Pollocked. By Lem Urtastik 16/2/07 / Created using Jackson Pollock artware by Miletos Manetas)

As with our previous experience of collective media arts ventures such as the first round of NODE.London Season of Media Arts (2006) [21] “we saw that lots of people invested with most enthusiasm in unstructured discourse; meandering and complex. This gave all participants a partial but meaningful view of the diverse contexts in which we worked, allowing us to make decisions about what our contribution could be. These many-to-many deep processes are never efficient but still invaluable to us in a culture where the pressures are always to be newer, faster, better-oiled, less philosophical, less human (ie less messy and complicated), more productive in the service of strategic overview.” (Garrett and Catlow) [ibid]

The next DIWO took place in 2009. It was called ‘Do It With Others (DIWO) at the Dark Mountain’. It was a collaboration between the then, newly formed ‘The Dark Mountain Project’, [22] Furtherfield and those participating in DIWO. A Dark Mountain manifesto grew out of a conversation between Paul Kingsnorth and Douglad Hine. It was an invitation to a new cultural response to the converging crises of climate change, resource scarcity and economic instability.

Paul Kingsnorth, in a letter to George Monbiot in the Guardian Newspaper which was also (openly) published by Monbiot said “As for saving the planet – what are we really trying to save, as we scrabble around planting turbines on mountains and shouting at ministers, is not the planet but our attachment to the western material culture, which we cannot imagine living without.” [23] The Dark Mountain Project wrote their Manifesto ‘UNCIVILISATION: the dark mountain manifesto’ “Old gods are rearing their heads, and old answers: revolution, war, ethnic strife. Politics as we have known it totters, like the machine it was built to sustain. In its place could easily arise something more elemental, with a dark heart.” [24] (DMP 2009)

The Dark Mountain Project has been viewed by many as apocalyptic, yet it also has grown in popularity these last few years. When discussing the project Hine says “Rather than treating these as distinct problems in need of technical solutions, we argued that they should be treated as symptoms of a deeper social and cultural crisis, a failure of the stories we have been telling ourselves for generations.” The Dark Mountain Project text was “addressed to other writers, and there is still a vein of Dark Mountain which is about finding new ways of writing, adequate to the times we are living through.” [25] (Hine 2009)

Kingsnorth and Hine both come from a literary background. Asking people to get involved in the project was a big ask.

DIWO E-Mail Art contributors in 2007 included: //indira, [–lo_y-], aabrahams, Alan Sondheim, Alexandra Reill, Allan Revich, Ana Valdes, Andre SC, Andrej Tisma, Ant Scott, arc.xolotl ARN, Aurlea, biodollsmouse, Bjorn Eriksson, Bjorn Magnhildoen, Blackmail, bob catchpole, bobig, brian@netart.org.uy, Camille Baker, Chris Fraser, Christphe Bruno, Clive McCarthy, cont3xt.net, Corrado Morgana, Daniel C. Boyer, dave miller, Denisa Kera, Dion Laurent, Eric Dymond, Edward Picot, Frederick Lesage, Geert Dekkers, Giles Askham, Giselle Beiguelman, Gregorios Pharmakis, Hans Bernhard, Helen Varley Jamieson, Hight, James Morris, janedapain, Jon Thomson, Jonathon Keats, Kanarinka, Kate Southworth, Lance W, Lauren A Wright, lem urtastic, Lewis LaCook, Lisa, Lizzie Hughes, Lorna Collins, Lucille C, Marc Garrett, Marc Cooley, Maria Chatzichristodoulou, mez breeze, Michael Szpakowski, Msdm, Neil Jenkins, patrick lichty, Paul Trevor, Regina Pinto, Riccardo Mantelli, Richard Osborne, rich white, Rosangela Aparecide da conceicao, Ruth Catlow, Sachiko Hayashi, Severn, Sim Gishel, Spread, Susana Mendes Silva, Taylor Nuttall, The Subversive Artist, Turbulence, Wolfgang, xavier cahen, zea.

A Mail-Art project across physical and digital networks in collaboration with the Dark Mountain Project; to question the stories that underpin our failing civilisation and to craft new ones for the age ahead.

This was the second Do It With Others (DIWO) E-Mail-Art project initiated by Furtherfield. The first DIWO experiment in 2007 extended the Do-It-Yourself ethos of early net art, characterised by curiosity, activism and precision, towards a more collaborative approach, using the Internet as an experimental artistic medium and distribution system to foment grass-roots creativity.

The Dark Mountain Project is ‘a new cultural movement for an age of global disruption.’ It aimed to ‘question the stories that underpin our failing civilisation, to craft new ones for the age ahead and to write clearly and honestly about our true place in the world.’ Do It With Others (DIWO) at the Dark Mountain, a mail-art project at HTTP Gallery, is a cultural collaboration for this age. “Uncivilisation,” the Dark Mountain Manifesto, called for a cultural response to our current predicament. Its challenge was offered to network-minded artists, technologists, writers and activists as a provocation – to work together to re-envision the narratives and infrastructures that govern our relationships with the natural world, and how they might be unravelled and rewoven to reconfigure our place in it. As “Uncivilisation” concludes, ‘the end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop.’

Artists, technologists, writers, activists and all other living beings were invited to correspond with each other across physical and digital mail networks, and the exhibition at HTTP present the results of this process. These have been gathered and the presentation devised during an Open Curation event, involving collaborators in real and virtual space. Transmissions shown in the exhibition include collaborative image-threads, net artworks, digital videos, drawings, paintings on wall and paper, sound works, and the full text of the discussion generated on the NetBehaviour list presented in numerous forms. The opening also featured a performance representing a central controversy arising during the project. The exhibition offered new myths and maps for future uncivilisation at HTTP Gallery.

More about The Dark Mountain Project and Furtherfield

The Dark Mountain Project is curated by Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine. http://www.dark-mountain.net

Paul is the author of One No, Many Yeses and Real England. He was deputy editor of The Ecologist between 1999 and 2001. His first poetry collection, Kidland, is forthcoming from Salmon Poetry.

Dougald writes the blog “Changing the World (and other excuses for not getting a proper job).” He is a former BBC journalist and co-founder of the School of Everything, and has written for and edited various online and offline magazines.

This project is part of Furtherfield’s on-going Media Art Ecologies programme, which aims to provide opportunities for critical debate, exchange and participation in emerging ecological media art practices, and the theoretical, political and social contexts they engage.

For details about the project, visit: http://http.uk.net/diwodarkmountain

For information about past events: 2009 | 2010

Do you want to Do It With Others in the future?

E-Mail: go to http://netbehaviour.org, subscribe to the NetBehaviour email list, correspond and join the explosive discussions in image, text, sound, movie and code.

An E-Mail-Art project on the NetBehaviour email list culminating in an exhibition at the HTTP Gallery in London.

Open Call for contributions from 31 January to 28 February 2007 via NetBehaviour email list.

Images from the show are – https://www.flickr.com/photos/http_gallery/albums/72157624491759868

Exhibition at HTTP Gallery in March 2007

The Do It With Others (DIWO) E-Mail-Art project aims to highlight the already thriving imaginations of those who use social networks and digital networks on the Internet as a form of distribution. Just like Mail Art, E-Mail-Art bridges the divide between artists and non-artists to share a freely accessible form of distribution.